Winter 2011

Editor's Note

"There is no quantum world,” said Danish physicist Neils Bohr. “It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how Nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about Nature.” [Emphases added] Despite this bothersome paradox, Bohr’s interpretation of quantum mechanics has been scientific orthodoxy for nearly a century. That’s quite long enough, according to physics professor Travis Norsen. In “An Embarrassment of Beables,” Travis challenges the “Copenhagen interpretation” of quantum mechanics and supports a less paradoxical theory first developed in 1926.

Challenging the dominant paradigm is a long-standing tradition in the sciences and indeed a familiar practice across all disciplines at Marlboro. In this issue of Potash Hill you will also learn about student Sari Brown’s efforts to confront social patterns of gender oppression in Bolivia, and alumna Daniella Martin’s crusade against species discrimination in the kitchen. Even Marlboro’s new ceramics professor, Martina Lantin, challenges trenchant dichotomies between art and craft, sculptural and functional, in her practice and in the classroom.

If you find something in this Potash Hill that challenges your own way of thinking, or have any other comments, please drop me a line. You can see reactions to the last issue on page 46.

—Philip Johansson, editor

Table of Contents

Summertime at Villa Roma

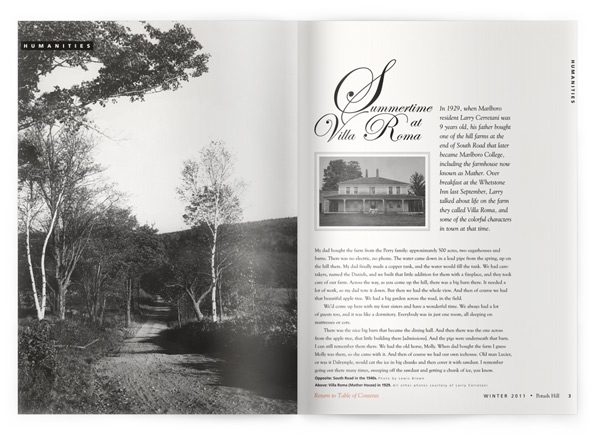

In 1929, when Marlboro resident Larry Cerretani was 9 years old, his father bought one of the hill farms at the end of South Road that later became Marlboro College, including the farmhouse now known as Mather. Over breakfast at the Whetstone Inn last September, Larry talked about life on the farm they called Villa Roma, and some of the colorful characters in town at that time.

My dad bought the farm from the Perry family: approximately 500 acres, two sugarhouses and barns. There was no electric, no phone. The water came down in a lead pipe from the spring, up on the hill there. My dad finally made a copper tank, and the water would fill the tank. We had caretakers, named the Daniels, and we built that little addition for them with a fireplace, and they took care of our farm. Across the way, as you come up the hill, there was a big barn there. It needed a lot of work, so my dad tore it down. But then we had the whole view. And then of course we had that beautiful apple tree. We had a big garden across the road, in the field.

We'd come up here with my four sisters and have a wonderful time. We always had a lot of guests too, and it was like a dormitory. Everybody was in just one room, all sleeping on mattresses or cots.

There was the nice big barn that became the dining hall. And then there was the one across from the apple tree, that little building there [admissions]. And the pigs were underneath that barn. I can still remember them there. We had the old horse, Molly. When dad bought the farm I guess Molly was there, so she came with it. And then of course we had our own icehouse. Old man Lucier, or was it Dalrymple, would cut the ice in big chunks and then cover it with sawdust. I remember going out there many times, sweeping off the sawdust and getting a chunk of ice, you know.

It was a beautiful field all the way down to the woods. We used to walk that way, go down and follow the brook, go way down to Harrisville [at the bottom of Moss Hollow Road], and then come back on the road. My dad would always have company up there, and we'd do that walk every so often. Some of the people we took there were, you know, they never did much walking. It would take us a few hours.

![]()

Henry Hughes had the adjoining farm, and his wife was a schoolteacher. Taught in the little schoolhouse next to Russell Hertzburg's [now President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell's house]. She was a big, strapping woman, and she was barefoot all the time. Went into the barn, all over the cow droppings and everything. Didn't bother her one bit. We'd get milk from them. Nice fresh milk. So we had a nice relationship with them. Henry did a lot for my dad. I can still see him out there with his scythe, cutting down hay in the field and giving it to the horses and cows.

Down the road was Reverend Christie. Just down the bottom of the hill. From there, you came up the road to the Hertzburgs. Mr. Hertzburg would walk up the hill and sit on the porch with my dad, and they would have a wonderful time talking about different things. He was a painter; he had a paint store in Brattleboro.

Then Lucier Road had Mr. and Mrs. Lucier and son Robert. Mr. Lucier was a violinist. Above them lived the Chase Brothers, Fred and Frank. They mowed our field for hay. Frank had just a little mustache, but Fred had a beard, and they were short people. At noon-time, Fred would sit down on the grass there, near that barn that's near the road, across from the apple tree, and have lunch: a can of beans, a hunk of cheese and bread. Oh boy, what a guy he was. We used to get over a hundred-some tons of hay, between the upper field and the lower field. I helped with the haying. And Mrs. Hughes, I can remember her on the horse and wagon. Helen would throw the hay up, and Henry would pack it down on the wagon. It was all loose. Always put it right in the barn there. It was quite a thing.

Up in back of the house, there were two sugarhouses. It was just beyond that-you know, all the woods up there-Helen Hughes always said there's an underground prison for the Indians. It was a cave-not a cave but a dungeon-like-went back to the 17- or 1800s maybe. Mrs. Hughes said it's somewhere up there, all built with stone, just a hole in the ground. It must still be there. I had an idea where the area was, but I could never find it.

![]()

South Road was all dirt, and this wide. It was a bumpy and narrow road-and muddy, I'm telling you. If you met a car you had to find a spot to back up and pull over. The old road would get so muddy, my dad got stuck in the mud. My dad always had a big car, a big Cadillac I guess it was; he had just bought my mom a new Persian coat. And so we got stuck and we're pushing the car. My mom's pushing the car in her new coat. The car went ahead and my mom went down in the mud [laughs].

There was a little bridge right there before you make the turn at where Lucier Road takes off. It was all wood planks. And you'd go "buddaboom-buddaboom." When company was coming, we could hear the bridge, "buddaboom-buddaboom," up at the farm. After you crossed it, you'd stop and put the planks back, because they're all loose.

We'd come up for winter for snow and stuff, but not too much. I spent some winters up here. Mrs. Hughes had a Morgan horse named Jack, and she'd hitch him up on a sleigh and we'd come up the road. And in the summer she'd come in a wagon.

We used to go to South Pond, go through the woods there, behind. Bob Lucier took care of horses for summer people. He and I would ride over there-go through the woods-or go down to Harrisville through the woods and then come back Moss Hollow Road. We'd go down to that little store down there and get Mule's Head Beer. And we'd come back on the road, because it would be dark. It was bumpy and, I'll tell you, full of ledge and rock. They've fixed it up beautifully now.

![]()

Walter Hendricks came into the picture in the late '30s. He came in from Chicago with his whole family. It took about four days to drive out here. The kids were all small. I forget how many children he had, four or five kids. And they were all little tots. A lovely family, and Walter was quite a guy. They bought Henry Hughes' place next door, then bought our farm from my dad.

I went into the service in '42, until '45. When I came out, Hendricks talked to my dad about selling the farm for the college. And that had to be '46 or '47. Hendricks would go down to New York to get money from different organizations. And he'd stop by to see my dad and visit. And of course, my dad was always writing a nice little check for him. He did that two or three times, I remember. From what I remember, when we sold I think the price was around $12,000. But my dad donated some money to the college too, because he was that type of person. My dad thought the idea of the college was a wonderful thing; that's why he did that.

Joining Larry at breakfast was innkeeper Jean Boardman, local resident Gussie Bartlett (wife of Bob Bartlett '52), alumni director Mark Genszler '95, sophomore film student Jesse Nesser, Potash Hill editor Philip Johansson, and alumni Bruce and Barbara Cole '59, who helped organize the event.

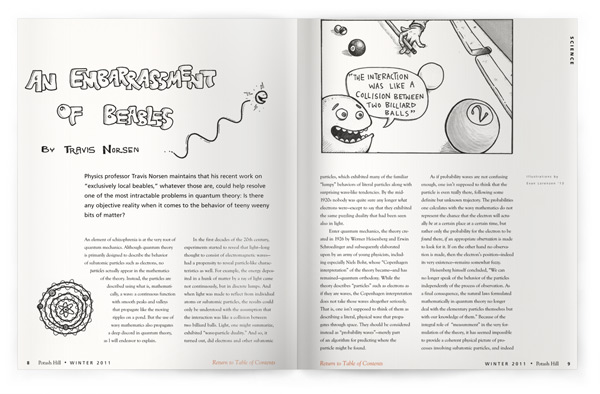

An Embarrassment of Beables

Physics professor Travis Norsen maintains that his recent work on “exclusively local beables,” whatever those are, could help resolve one of the most intractable problems in quantum theory: Is there any objective reality when it comes to the behavior of teeny weeny bits of matter?

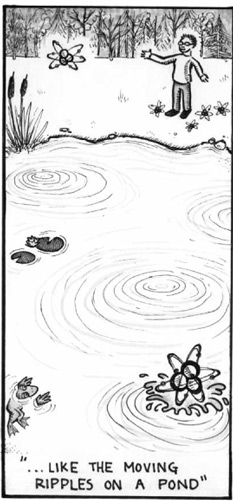

An element of schizophrenia is at the very root of quantum mechanics. Although quantum theory is primarily designed to describe the behavior of subatomic particles such as electrons, no particles actually appear in the mathematics of the theory. Instead, the particles are described using what is, mathematically, a wave: a continuous function with smooth peaks and valleys that propagate like the moving ripples on a pond. But the use of wavy mathematics also propagates a deep discord in quantum theory, as I will endeavor to explain.

In the first decades of the 20th century, experiments started to reveal that light—long thought to consist of electromagnetic waves—had a propensity to reveal particle-like characteristics as well. For example, the energy deposited in a hunk of matter by a ray of light came not continuously, but in discrete lumps. And when light was made to reflect from individual atoms or subatomic particles, the results could only be understood with the assumption that the interaction was like a collision between two billiard balls. Light, one might summarize, exhibited “wave-particle duality.” And so, it turned out, did electrons and other subatomic particles, which exhibited many of the familiar “lumpy” behaviors of literal particles along with surprising wave-like tendencies. By the mid-1920s nobody was quite sure any longer what electrons were—except to say that they exhibited the same puzzling duality that had been seen also in light.

Enter quantum mechanics, the theory created in 1926 by Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schroedinger and subsequently elaborated upon by an army of young physicists, including especially Niels Bohr, whose “Copenhagen interpretation” of the theory became—and has remained—quantum orthodoxy. While the theory describes “particles” such as electrons as if they are waves, the Copenhagen interpretation does not take those waves altogether seriously. That is, one isn’t supposed to think of them as describing a literal, physical wave that propagates through space. They should be considered instead as “probability waves”—merely part of an algorithm for predicting where the particle might be found.

As if probability waves are not confusing enough, one isn’t supposed to think that the particle is even really there, following some definite but unknown trajectory. The probabilities one calculates with the wavy mathematics do not represent the chance that the electron will actually be at a certain place at a certain time, but rather only the probability for the electron to be found there, if an appropriate observation is made to look for it. If on the other hand no observation is made, then the electron’s position—indeed its very existence—remains somewhat fuzzy.

As if probability waves are not confusing enough, one isn’t supposed to think that the particle is even really there, following some definite but unknown trajectory. The probabilities one calculates with the wavy mathematics do not represent the chance that the electron will actually be at a certain place at a certain time, but rather only the probability for the electron to be found there, if an appropriate observation is made to look for it. If on the other hand no observation is made, then the electron’s position—indeed its very existence—remains somewhat fuzzy.

Heisenberg himself concluded, “We can no longer speak of the behavior of the particles independently of the process of observation. As a final consequence, the natural laws formulated mathematically in quantum theory no longer deal with the elementary particles themselves but with our knowledge of them.” Because of the integral role of “measurement” in the very formulation of the theory, it has seemed impossible to provide a coherent physical picture of processes involving subatomic particles, and indeed questionable whether there is even any such realm of microscopic objective reality.

There exists an alternative theory of quantum phenomena, however, which has none of the measurement problems of the Copenhagen theory but makes precisely the same experimental predictions. Indeed, this alternative invites just the opposite kinds of philosophical extrapolations: Particles are really particles (whether anybody is looking at them or not), no special role is played by observation or measurement, and God (much to Einstein’s delight) does not play dice. The theory was first put forward by Louis de Broglie, also in 1926, but he was talked out of it by supporters of the Copenhagen view. It was independently rediscovered in 1952 by David Bohm and found its greatest champion in the physicist John Stewart Bell, starting in the 1960s.

Bell wrote: “Bohm’s 1952 papers on quantum mechanics were for me a revelation. [They eliminated] any need for a vague division of the world into ‘system’ on the one hand, and ‘apparatus’ or ‘observer’ on the other.” The need for such a “vague division” was, of course, just the point on which all orthodox quantum philosophy rested. But from Bell’s point of view, the contrast provided by the de Broglie-Bohm theory brought to light how unnecessary—indeed, how silly and unscientific—it was to posit a division between “measurement” and “non-measurement” as part of an allegedly fundamental physical theory.

For example, consider how the orthodox theory treats a simple situation such as the infamous double-slit experiment: A particle is fired toward a screen with two parallel slits in it, behind which lies a detection screen such as the CCD array in your digital camera. The Copenhagen mathematics says that the particle propagates along as a wave, splitting in half and going through both of the two slits. But then the CCD array measures the particle itself, causing the wave to collapse, rather like a balloon pricked with a pin that suddenly deflates down to a single point. The very mathematical formulation of Copenhagen quantum mechanics involves a fundamental distinction between physical processes that are measurements and those that aren’t, producing the infamous quantum jumps.

For example, consider how the orthodox theory treats a simple situation such as the infamous double-slit experiment: A particle is fired toward a screen with two parallel slits in it, behind which lies a detection screen such as the CCD array in your digital camera. The Copenhagen mathematics says that the particle propagates along as a wave, splitting in half and going through both of the two slits. But then the CCD array measures the particle itself, causing the wave to collapse, rather like a balloon pricked with a pin that suddenly deflates down to a single point. The very mathematical formulation of Copenhagen quantum mechanics involves a fundamental distinction between physical processes that are measurements and those that aren’t, producing the infamous quantum jumps.

Bell’s point, in effect, was this: What the heck is a “measurement?” This just isn’t the kind of concept one expects to show up in the fundamental laws of microphysics, because it is anthropocentric: “Making measurements” is something people do, not something electrons or the laws governing their behavior ought to know or care about. Bell asked, with tongue in the vicinity of cheek: “What exactly qualifies some physical systems to play the role of ‘measurer’? Was the wave function of the world waiting to jump for thousands of millions of years until a single-celled living creature appeared? Or did it have to wait a little longer, for some better qualified system . . . with a Ph.D.?”

If one can have quantum physics (including its amazing predictive and indeed practical powers) without the fuzzy quantum philosophy, why haven’t more physicists adopted the alternative viewpoint? One possible source of discomfort is known as a “beable” (a term Bell coined that rhymes with “agreeable,” not “feeble”), which brings us finally to some recent work I’ve done. In deliberate contrast to the “observables,” which play an absurdly central role in the formalism of standard quantum mechanics, beables are all those elements in a theory that are supposed to be taken seriously—as corresponding to things that really exist physically, whether anyone is observing them or not.

Bell argued that in the Copenhagen quantum theory, it’s just not clear what the beables are, i.e., which elements in the theory (if any) are supposed to correspond to physically real things. The wave function, for example, is kept in deliberate limbo between the physical and the mental: It’s a mere “probability wave” (whatever that means). In the de Broglie-Bohm theory, by contrast, the ontological status of things is clear: The beables of the theory include both the particles and the guiding wave field. Both of these can and indeed must be thought of as referring to physical objects that exist and interact in the same way all the time, regardless of whether any observations or measurements are happening. It’s just an ordinary physics theory of the sort that any sensible person would have expected prior to being exposed to the Copenhagen philosophy.

But still there’s a puzzle. The particles in the de Broglie-Bohm theory are what Bell called “local beables.” This means that they exist and move around in ordinary, three-dimensional physical space. But the wave field that guides them—that is, the usual quantum mechanical wave function obeying Schroedinger’s equation—is by contrast a “non-local beable.” This means it exists not in ordinary, three-dimensional physical space, but . . . somewhere else. Mathematically, the wave is a function not just of the three spatial dimensions (x, y and z, say) but rather of the coordinates of all the particles simultaneously: The x coordinate of particle 1, the y coordinate of particle 1, the z coordinate of particle 1, the x coordinate of particle 2, and so on. For a Bohmian universe containing N particles, then, the wave function exists in a space of not three but 3N dimensions.

The “out of this world” character of the wave function has been an embarrassment for people wanting to take the wave function as a beable since the very beginning of quantum mechanics. For example, in the months after Schroedinger first proposed his eponymous equation in 1926, Einstein was contemplating the possibility that the role of the wave function might be to steer individual particles, as in the mature de Broglie-Bohm theory. He rejected this possibility, however, on the grounds that one simply couldn’t take seriously the idea of a physically real wave living in this abstract, high-dimensional space: “Schroedinger is, in the beginning, very captivating. But the waves in n-dimensional coordinate space are indigestible . . . ”

Later, in the 1960s, after Bohm had rediscovered and developed the pilot-wave picture and was lobbying for it as an alternative to the Copenhagen theory, Heisenberg criticized it on these same grounds. And this, more or less, is how things have stood since. Most physicists have remained simply unaware of the existence of the de Broglie-Bohm alternative to Copenhagen quantum physics, and most of those who are aware of it have dismissed it on erroneous grounds—that it conflicts with relativity theory (actually a problem with all current theories of quantum mechanics). A very small minority of physicists, however, has perceived the theory’s great virtues and has thus developed and championed it, learning to live, as it were, with the embarrassment of needing to accept the wave function as a non-local beable.

Later, in the 1960s, after Bohm had rediscovered and developed the pilot-wave picture and was lobbying for it as an alternative to the Copenhagen theory, Heisenberg criticized it on these same grounds. And this, more or less, is how things have stood since. Most physicists have remained simply unaware of the existence of the de Broglie-Bohm alternative to Copenhagen quantum physics, and most of those who are aware of it have dismissed it on erroneous grounds—that it conflicts with relativity theory (actually a problem with all current theories of quantum mechanics). A very small minority of physicists, however, has perceived the theory’s great virtues and has thus developed and championed it, learning to live, as it were, with the embarrassment of needing to accept the wave function as a non-local beable.

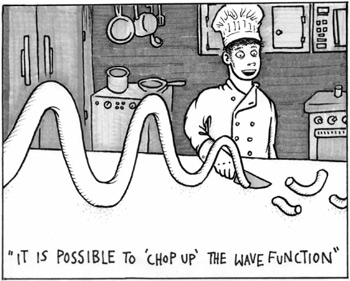

Not one to tolerate embarrassment, I began to meditate on this problem some years ago, and eventually made a small but perhaps important breakthrough. By means of what can only be described as a mathematical trick (which, for students who have taken calculus, amounts to the use of Taylor expansions), it is possible to “chop up” the wave function (on the 3N-dimensional space) into a number of distinct functions that live in ordinary three-dimensional space. That is, it is possible to mathematically rewrite the de Broglie-Bohm theory with a number of local beables—namely, waves propagating in physical space—in place of the non-local beable of the traditional formulation.

That was the good news. The bad news was that the number of distinct wave fields that resulted from the “chopping up” operation was itself rather embarrassing: An infinite number of such fields are required to achieve mathematical equivalence with the usual formulation. And there are other embarrassments as well: The particular mathematical “chopping up” operation I used will only work if one ignores a property called “spin” that particles are known to possess. There areseveral other features that only add to the feeling that the proposal is impossible to take too seriously as a candidate theory. But hey, Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Despite its many problems, the new perspective on the de Broglie-Bohm theory makes what I think is a crucial point of principle: The Schroedinger wave function can (to use Einstein’s phrase) “be transplanted from the n-dimensional coordinate space to the three . . . dimensional.” It’s not impossible. My goal in pursuing and reporting on this research has been an admittedly unserious and tentative proof that the kind of theory sought after by Einstein—a “theory of exclusively local beables”—is maybe not as out of reach as people seem to have assumed. My intention is to reignite this long-forgotten but prematurely abandoned research program. Only time will tell where it might lead, but the hope is that with a little work—almost certainly by people smarter than I—a really plausible, nice-looking theory of exclusively local beables could be constructed. This would go a long way toward making quantum theory more “digestible.”

Despite its many problems, the new perspective on the de Broglie-Bohm theory makes what I think is a crucial point of principle: The Schroedinger wave function can (to use Einstein’s phrase) “be transplanted from the n-dimensional coordinate space to the three . . . dimensional.” It’s not impossible. My goal in pursuing and reporting on this research has been an admittedly unserious and tentative proof that the kind of theory sought after by Einstein—a “theory of exclusively local beables”—is maybe not as out of reach as people seem to have assumed. My intention is to reignite this long-forgotten but prematurely abandoned research program. Only time will tell where it might lead, but the hope is that with a little work—almost certainly by people smarter than I—a really plausible, nice-looking theory of exclusively local beables could be constructed. This would go a long way toward making quantum theory more “digestible.”

Travis Norsen teaches physics and astronomy at Marlboro, and recently authored a textbook tracing the history, development and applications of Newton’s theory of universal gravitation and the atomic theory of matter. To learn more about Travis’ work on exclusively local beables, click the links on his faculty profile at www.marlboro.edu/academics/faculty/norsen_travis/

Unintuitive but elegant math

The Rez

Excerpts from Views from the Reservation

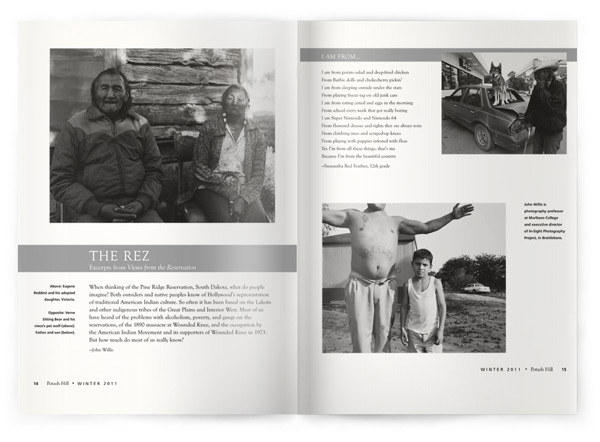

When thinking of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, what do people imagine? Both outsiders and native peoples know of Hollywood’s representation of traditional American Indian culture. So often it has been based on the Lakota and other indigenous tribes of the Great Plains and Interior West. Most of us have heard of the problems with alcoholism, poverty, and gangs on the reservations, of the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee, and the occupation by the American Indian Movement and its supporters of Wounded Knee in 1973. But how much do most of us really know? —John Willis

I am from…

I am from potato salad and deep-fried chicken

From Barbie dolls and chokecherry pickin’

I am from sleeping outside under the stars

From playing freeze tag on old junk cars

I am from eating cereal and eggs in the morning

From school every week that got really boring

I am Super Nintendo and Nintendo 64

From flowered dresses and tights that are always torn

From climbing trees and scraped-up knees

From playing with puppies infested with fleas

Yes I’m from all these things, that’s me

Because I’m from the beautiful country

—Samantha Red Feather, 12th grade

Be Thankful

You have to say a prayer of Thanksgiving.

You have to be thankful

Otherwise it’s like a house without windows.

It’s dark

In the morning when you wake up from a good

night’s sleep, you open

Your eyes and you see the light.

Say a prayer of thanksgiving before you get up.

Thank you. Thank you Tunkasila for another day.

—Victoria Chipps, elder

In the Struggle, We Stand

In the struggle we stand, shields and shawls

It’s in the struggle great duty calls

It’s a duty to Oyate, a duty to the people

Use your head Sitting Bull said

Find what’s lost, move us ahead

Cause there’s more to history

Than what meets the book

There’s a blizzard blowing hard

And it’s 100 degrees

In the struggle we stand kin to kin

Struggle to stand through strength from within

Look back to where and why, when and how

Hold on to what’s dear, c’anupa in our hearts

Families rent asunder, cultures ripped apart

In the struggle we stand, seven generations thence

Diplomas and degrees and learned and smart

We talk and we read and glean from past days

We find where we are and where we’ve been

In the struggle we stand

—Lavelle Warrior, 9th grade

Photos, poems and narrative excerpted from Views from the Reservation, by John Willis. Center for American Places: Chicago, 2010. John Willis is photography professor at Marlboro College and executive director of In-Sight Photography Project, in Brattleboro.

Gender Dialogues in Bolivia

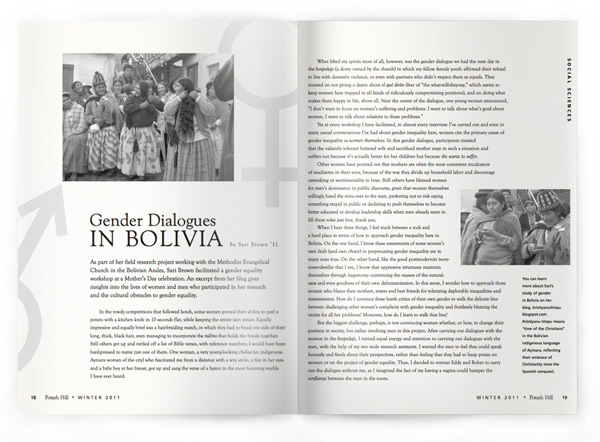

by Sari Brown ‘11

As part of her field research project working with the Methodist Evangelical Church in the Bolivian Andes, Sari Brown facilitated a gender equality workshop at a Mother’s Day celebration. An excerpt from her blog gives insights into the lives of women and men who participated in her research and the cultural obstacles to gender equality.

In the rowdy competitions that followed lunch, some women proved their ability to peel a potato with a kitchen knife in 10 seconds flat, while keeping the entire skin intact. Equally impressive and equally brief was a hair-braiding match, in which they had to braid one side of their long, thick, black hair, even managing to incorporate the tullma that holds the braids together. Still others got up and rattled off a list of Bible verses, with reference numbers; I would have been hard-pressed to name just one of them. One woman, a very young-looking cholita (an indigenous Aymara woman of the city) who fascinated me from a distance with a wry smile, a fire in her eyes and a baby boy at her breast, got up and sang the verse of a hymn in the most haunting warble I have ever heard.

What lifted my spirits most of all, however, was the gender dialogue we had the next day in the hospedaje (a dorm owned by the church) in which my fellow female youth affirmed their refusal to live with domestic violence, or even with partners who didn’t respect them as equals. They insisted on not giving a damn about el qué dirán (fear of “the what-will-they-say,” which seems to keep women here trapped in all kinds of ridiculously compromising positions), and on doing what makes them happy in life, above all. Near the outset of the dialogue, one young woman announced, “I don’t want to focus on women’s suffering and problems. I want to talk about what’s good about women. I want to talk about solutions to these problems.” Yet at every workshop I have facilitated, in almost every interview I’ve carried out and even in many casual conversations I’ve had about gender inequality here, women cite the primary cause of gender inequality as women themselves. In this gender dialogue, participants insisted that the valiantly tolerant battered wife and sacrificed mother stays in such a situation and suffers not because it’s actually better for her children but because she wants to suffer.

Other women have pointed out that mothers are often the most consistent inculcators of machismo in their sons, because of the way they divide up household labor and discourage caretaking or sentimentality in boys. Still others have blamed women for men’s dominance in public discourse, given that women themselves willingly hand the reins over to the men, preferring not to risk saying something stupid in public or declining to push themselves to become better educated or develop leadership skills when men already seem to fill those roles just fine, thank you.

When I hear these things, I feel stuck between a rock and a hard place in terms of how to approach gender inequality here in Bolivia. On the one hand, I know these assessments of some women’s own fault (and own choice) in perpetuating gender inequality are in many ways true. On the other hand, like the good postmodernist ivory-tower-dweller that I am, I know that oppressive structures maintain themselves through hegemony—convincing the masses of the naturalness and even goodness of their own dehumanization. In this sense, I wonder how to approach those women who blame their mothers, sisters and best friends for tolerating deplorable inequalities and mistreatment. How do I convince these harsh critics of their own gender to walk the delicate line between challenging other women’s complicity with gender inequality and fruitlessly blaming the victim for all her problems? Moreover, how do I learn to walk that line?

But the biggest challenge, perhaps, is not convincing women whether, or how, to change their position in society, but rather involving men in this project. After carrying out dialogues with the women in the hospedaje, I turned equal energy and attention to carrying out dialogues with the men, with the help of my two male research assistants. I wanted the men to feel they could speak honestly and freely about their perspectives, rather than feeling that they had to heap praise on women or on the project of gender equality. Thus, I decided to entrust Eddy and Rober to carry out the dialogue without me, as I imagined the fact of my having a vagina could hamper the confianza between the men in the room.

One morning, on a national holiday, we managed to wake some eight or so of the hospedaje boys. As might be expected from their reluctance to participate, the men weren’t quite as enthusiastic or thoughtful in their responses as I would have liked. Part of the problem, I realized, was my assistants’ lack of understanding and ability to clarify the theoretical concepts they presented. But in addition, a factor that we could not control was that all of the men maintained an uncritical denial of the existence of any significant problems with gender inequality hoy en día (in this day and age).When Eddy and Rober asked for examples of the differences between men and women according to their cultural context, most of the men failed to elaborate even on such “givens” as women’s place in the house and men’s place at work, or women’s sentimentality and men’s stoicism. Most of them simply said, “Really, hoy en día, there is no difference between men and women. Women have all the same rights and can do all the same things men do.” Given that I had just finished reading a laborious, 175-page sociological report on the gender breach in all aspects of Bolivian society, this response on the part of my hermanos made me want to bang my head against the wall. The report indicated, for example, that women politicians are customarily sexually harassed to intimidate them into stepping down, that men in the majority of couples have control over family planning, and that seven of every ten women have experienced violence in the home.

I realize that the problem is a structural one. Just as women who seem to choose to remain in a position of subordination can’t be personally blamed for this choice, men can’t be personally blamed for their uncritical consent to a system of inequality that is as natural to them as the thin highland air. Nonetheless, although it may be no man’s intention, I found that even basically decent men in this community engage in concrete actions and behaviors that serve to oppress women. This would need to be addressed if the radical egalitarian vision espoused by the Methodist Evangelical Church is to be realized, a vision that is particularly relevant to the marginalized indigenous communities that make up the Church’s majority.

Gender dialogues can help elaborate and clarify cultural ideals, and they can also help concientizar the participants (make them aware) and thus eventually change practices and entire realities. However, the most significant factor is how we, as men and women, actually relate to each other on a day-to-day basis, and how we might implement change into habits that seem as old as time. As Eddy always says, “Gender inequality comes from antes (before), from our ancestors, from the way it’s always been.” But stereotypes, social structures and cultural norms aren’t people. People are much more mercurial, quirky, adaptable and ultimately joyful in their daily lives.

Maybe gender theorists have much to say about how the woman in El Alto who won the potato-peeling contest is seriously, tragically limited to finding her worth only in menial domestic tasks. But that devilish grin on her face as she stripped that potato naked and let a perfect, continuous spiral of skin drop to the ground was enough to convince me that she genuinely does find joy in her everyday potato-peeling life. The differences between men’s and women’s opinions as voiced in a gender dialogue are only a tiny part of the story of how they relate to each other, love each other and infuriate each other “in this day and age.”

You can learn more about Sari’s study of gender in Bolivia on her blog, kristiyanutimpu.blogspot.com. Kristiyanu timpu means “time of the Christians” in the Bolivian indigenous language of Aymara, reflecting their embrace of Christianity since the Spanish conquest.

Dismantling oppression in Oregon

“Bringing injustices to light is contagious, buoyant and spreading,” said Choya Adkison-Stevens ’04, a community engagement coordinator at the YWCA of Greater Portland. After four years as a primary advocate at the Y’s domestic violence shelter, Choya’s new role allows her to branch out and start exciting new projects, including training communities on elder abuse, survivor-centered services and housing advocacy. “I am constantly striving to meet people right where they are, with the right mix of compassion, information, openness, humor, gravity—and sometimes succeeding. I know I’ve done well when I get a phone call from a woman I worked with four years ago (as happened last week) and she just wants to check in, catch me up on her kids’ lives, let me know she’s ok.”

Entomophagy: Guess who’s crawling to dinner

by Daniella Martin ’02

Raising livestock currently takes up two-thirds of the available arable land on our planet, and this measure is rising. Professor Arnold Van Huis, a Dutch entomologist, has suggested that if we continue eating the way we do, we will soon need a whole other Earth to sustain ourselves. We don’t have one, and this is where bugs come in.

That’s right, bugs. I first learned about insect-eating, or entomophagy (en•toe•móff•a•gee), through my Plan studies in anthropology. I spent eight months in the Yucatan, trying to catch a glimpse of surviving vestiges of pre-Columbian food and medicine; one of these surviving vestiges turned out to be the consumption of insects. In fact, some researchers investigating historic cannibalism in the region argue that dietary protein was adequate with the supplementation of insects, making cannibalism more culture than craving. The idea of eating insects stuck with me, and in time I realized that entomophagy was a perfect union of so many interests I valued: culture, nutrition, ecology and having something cool to talk about at dinner parties. It was at this point that my involvement began in earnest.

When I do live presentations on the subject, I always like to begin by asking for a show of hands: Who thinks eating bugs is weird? Most of the hands go up—of course it’s weird. I then hit them with the fact that 80 percent of the world’s population eats bugs. On the pie chart of bug-eaters versus bug-snubbers, Westerners get the significantly smaller slice. Throughout Latin America, Asia and Africa particularly, bugs aren’t swatted off the menu. That makes us the minority here; we’re the weirdos. Of course, Westerners are not known for our conscientious (or even conscious) consumption of energy or other natural resources. Why would we do something so inherently eco-logical as to include the planet’s most efficient, sustainable and abundant source of animal protein in our diets? While it takes up to 10 pounds of grain to produce one pound of beef, it takes a mere two pounds of feed to produce the same pound of crickets. This cricket-fodder could easily be vegetable waste that humans would normally throw away, the by-products of other food. Although this pound of bugs may be somewhat less protein-dense than beef, it has several times the levels of iron and calcium. Bugs need less food than cows (and pigs, and chickens) because they are ectothermic: They don’t need to heat their blood in order to live. All the energy that livestock “waste” on blood-heating, bugs put straight into growing bigger, faster. Incidentally, because of this basic biological difference, insects also produce far fewer greenhouse-gas emissions.

While it takes up to 10 pounds of grain to produce one pound of beef, it takes a mere two pounds of feed to produce the same pound of crickets. This cricket-fodder could easily be vegetable waste that humans would normally throw away, the by-products of other food. Although this pound of bugs may be somewhat less protein-dense than beef, it has several times the levels of iron and calcium. Bugs need less food than cows (and pigs, and chickens) because they are ectothermic: They don’t need to heat their blood in order to live. All the energy that livestock “waste” on blood-heating, bugs put straight into growing bigger, faster. Incidentally, because of this basic biological difference, insects also produce far fewer greenhouse-gas emissions.

In addition to the 10-to-1 ratio for grain, ecologist Nina Munteanu estimates that it could take nearly 900 gallons of water to produce a third of a pound of beef, or one big hamburger. Comparatively, she says, “A quarter-pound of crickets only requires a moist paper towel, refreshed weekly.” That’s a water savings of, what, over 1,000 percent?

As if that weren’t enough, let’s add a few more factors into the mix. While livestock need a large amount of space to roam around (not to mention to grow their food), insects can live quite comfortably in small spaces, which can be vertically stacked. Another advantage bugs have is rapid reproduction. Compared to a beef cow, which typically produces one calf each year, a female cricket can lay 1,500 eggs a month. It is for all these reasons that David Gracer of Small Stock Food Strategies says that when it comes to food production, “Cows and pigs are the SUVs; bugs are the bicycles.”

Our aversion to insects as food is purely cultural. Like the frog that will starve to death while surrounded by dead flies because it can’t recognize them as food, we are trapped within a matrix of perception. But, unlike the frog, our perceptions can change: The early American colonists were initially horrified by the lobsters they found washed up on the shore—these were considered famine food at best. Now they’re the most expensive thing on the menu.

The more I eat and study insects, the more I respect and admire them. I envision a future where world hunger has been solved, and where most produce is naturally organic due to the “second harvest” of insects on every crop. I mean hey, if you can’t beat ’em, eat ’em!

Daniella Martin received her degree in anthropology and is the host of Girl Meets Bug, the invertebrate cooking and travel show. So far she has eaten crickets, cockroaches, fly pupae, wax worms, mealworms, silkworms, bamboo worms, grasshoppers, walking sticks, katydids, scorpions, snails, cicadas, leaf-cutter ants, ant pupae, dung beetles, termites, wasps and wasp brood, butterfly caterpillars, dragonflies and water beetles. Learn more at www.girlmeetsbug.com.

On & Off the Hill

Newsy articles from Marlboro and around the world, including a fond farewell to history professor Tim Little, a report from students in China, a class in community-based performance and a new professor of ceramics, Martina Lantin.

Newsy articles from Marlboro and around the world, including a fond farewell to history professor Tim Little, a report from students in China, a class in community-based performance and a new professor of ceramics, Martina Lantin.

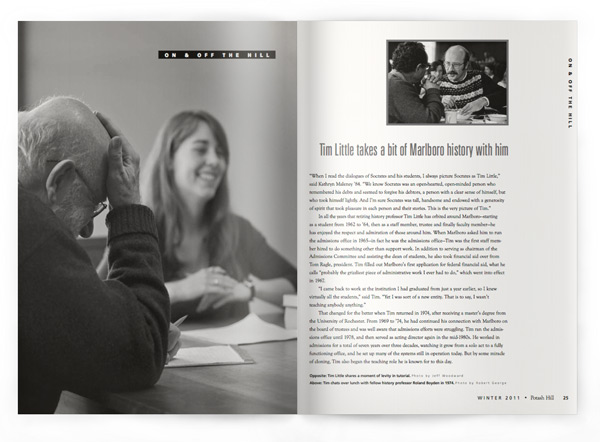

Tim Little takes a bit of Marlboro history with him

“When I read the dialogues of Socrates and his students, I always picture Socrates as Tim Little,” said Kathryn Maleney ’84. “We know Socrates was an open-hearted, open-minded person who remembered his debts and seemed to forgive his debtors, a person with a clear sense of himself, but who took himself lightly. And I’m sure Socrates was tall, handsome and endowed with a generosity of spirit that took pleasure in each person and their stories. This is the very picture of Tim.”

In all the years that retiring history professor Tim Little has orbited around Marlboro—starting as a student from 1962 to ’64, then as a staff member, trustee and finally faculty member—he has enjoyed the respect and admiration of those around him. When Marlboro asked him to run the admissions office in 1965—in fact he was the admissions office—Tim was the first staff member hired to do something other than support work. In addition to serving as chairman of the Admissions Committee and assisting the dean of students, he also took financial aid over from Tom Ragle, president. Tim filled out Marlboro’s first application for federal financial aid, what he calls “probably the grizzliest piece of administrative work I ever had to do,” which went into effect in 1967.

“I came back to work at the institution I had graduated from just a year earlier, so I knew virtually all the students,” said Tim. “Yet I was sort of a new entity. That is to say, I wasn’t teaching anybody anything.” That changed for the better when Tim returned in 1974, after receiving a master’s degree from the University of Rochester. From 1969 to ’74, he had continued his connection with Marlboro on the board of trustees and was well aware that admissions efforts were struggling. Tim ran the admissions office until 1978, and then served as acting director again in the mid-1980s. He worked in admissions for a total of seven years over three decades, watching it grow from a solo act to a fully functioning office, and he set up many of the systems still in operation today. But by some miracle of cloning, Tim also began the teaching role he is known for to this day.

That changed for the better when Tim returned in 1974, after receiving a master’s degree from the University of Rochester. From 1969 to ’74, he had continued his connection with Marlboro on the board of trustees and was well aware that admissions efforts were struggling. Tim ran the admissions office until 1978, and then served as acting director again in the mid-1980s. He worked in admissions for a total of seven years over three decades, watching it grow from a solo act to a fully functioning office, and he set up many of the systems still in operation today. But by some miracle of cloning, Tim also began the teaching role he is known for to this day.

Tim relished the opportunity to teach with history professor Roland Boyden, his Plan sponsor and mentor in so many ways. Roland was the first faculty member ever hired and was also the first dean of the faculty. Roland’s daughter Rachel Boyden ’79 remembers Tim coming to their house in Cambridge to work on his Plan when her father was on sabbatical, in 1964. “Tim is a link to the early years of Marlboro,” she said. “It will certainly make the whole experience of history at the college different when he retires.”

“Tim offered the yang to Roland’s yin,” said Peter Mallary ’76, one of Tim’s first Plan students and father of Rebecca Mallary ’11, one of Tim’s final Plan students. “Where Roland was economical, Tim was expansive. While both were generous with their time and teaching, the first was an introvert and the second a decided extrovert. Tim has an openness—particularly with students—that is infectious. There is always a story or an observation of a curious, amusing and sometimes trenchant sort. He is a gifted raconteur.”

“Because it suited me to do it this way, and Roland did it this way, if a student came to me with an interest that was historical, I would be willing to work with that student if I could be persuaded that he or she would work hard too,” said Tim. “The fact that I knew as little about it as they did at the beginning couldn’t prevent us from getting somewhere. I’ve very seldom been let down. I’ve had some wonderful students over the years.” Jeff Bower ’92 credits Tim with helping him learn how to learn. “Tim is the very quintessence of Marlboro College,” he said. “Here is a man capable of sharing a great breadth and depth of knowledge within his field while at the same time allowing students to learn along their own path. He guided without boundaries, encouraged the articulation and development of ideas and presented cause and effect, while at the same time realizing that the linearity with which history is sometimes presented is never how history actually happens.”

Jeff Bower ’92 credits Tim with helping him learn how to learn. “Tim is the very quintessence of Marlboro College,” he said. “Here is a man capable of sharing a great breadth and depth of knowledge within his field while at the same time allowing students to learn along their own path. He guided without boundaries, encouraged the articulation and development of ideas and presented cause and effect, while at the same time realizing that the linearity with which history is sometimes presented is never how history actually happens.”

Although Tim began in European history, his interests were continually broadened by his students’ interests and by collaborations with other faculty members. He covered Asian history with some students, Native American history with others, and “gaily danced into” lots of Anglo-American history working alongside American studies professor Dick Judd. “As it became more and more evident that history was being written and discussed on a broader and broader scope, it wasn’t so unusual that I should go into world history,” said Tim. “Everybody was doing it, and Marlboro was building up to the World Studies Program. It made sense in a way that it really didn’t before.”

“Tim gave me a new perspective on how to ‘read’ history—an important tool for critical thinking,” said trustee Sara Coffey ’90. Sara was one of the first students in the World Studies Program, and, because she started midyear, had to take the first semester of the required World History and Cultures as a tutorial with Tim. “I still see him engaging with students with the same generosity that I experienced. He has not lost that mischievous sparkle either.”

The launching of the World Studies Program had a particular sparkly significance for Tim that he didn’t know at the time, as it brought in cultural history and Eurasian studies professor Dana Howell, whom he married a few years later. “Dana and I worked well together. We taught this huge class together for World Studies, which involved grading papers and spilling all sorts of things.” Over the years, Tim has always embodied the community spirit at Marlboro. He was a highly respected Town Meeting moderator and led a “breakfast club” chat in the dining hall every morning he was on campus. He was also a devoted emcee for the annual day-care bake sale, according to Gina DeAngelis ’94, who wrote the script for him one year.

Over the years, Tim has always embodied the community spirit at Marlboro. He was a highly respected Town Meeting moderator and led a “breakfast club” chat in the dining hall every morning he was on campus. He was also a devoted emcee for the annual day-care bake sale, according to Gina DeAngelis ’94, who wrote the script for him one year.

“He was far funnier off the cuff than anything I’d written,” said Gina. “He also ended up bidding on a cake I made, and the next day in the dining hall, he came up to me in front of a dozen people and sang my praises for five solid minutes: I was definitely, he said, no matter what other things I’d ever done, going to go to heaven, solely because of that cake. I will be forever grateful to him for his gentle guidance, his warm sense of humor and his unparalleled joie de vivre.”

Now with a little more time on his hands, Tim is looking forward to being with his three grandsons and reading the “piles and piles of things” he’s collected in case he found himself retired. He is also interested in getting certified to teach children to read, and understands that there is a demand for older men in that field. “Sometimes the students get cranky with their female teachers, and an old, grim-looking man like me will give some gravity to it.”

For many years Tim has been working on writing a history of Marlboro College, and it is hard to imagine a person better equipped in aptitude and experience to do so. “The problem is that every time I sit down to write a history I end up writing a memoir,” said Tim. “And when I say, oh hell, I’ll just write a memoir to get it out of the way, the history keeps intervening again.” We await both with great anticipation.

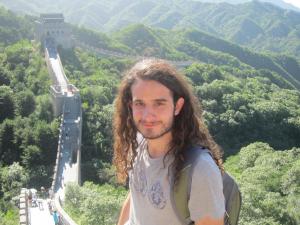

Language students find context in China

“I felt like an expatriate, like Hemingway or some other Lost Generation type in Paris,” said junior Casey Friedman, referring to his trip to China with four other Marlboro students last summer. “There I was with a small band of my countrymen, surrounded by a foreign world into which we didn’t quite fit. And it was magnificent.”

“I felt like an expatriate, like Hemingway or some other Lost Generation type in Paris,” said junior Casey Friedman, referring to his trip to China with four other Marlboro students last summer. “There I was with a small band of my countrymen, surrounded by a foreign world into which we didn’t quite fit. And it was magnificent.”

The students joined Chinese language professor Grant Li for six weeks at the International Cultural Exchange School at Changchun University, in Jilin Province, thanks to support from the Freeman Foundation Undergraduate Asian Studies Initiative. Every morning they had Chinese classes with other students at the school, most of them from Korea and Russia, and in the afternoon they enjoyed cultural activities ranging from kung fu and calligraphy to making dumplings.

“The experience was more about the culture than the language,” said Grant. “Language is a gradual thing, and the instruction was hard for them because the teachers never spoke English. But culturally, you can see the way of life right away. They lived there. They learned where to go, what people were doing.”

The students became adept at ordering food at restaurants, haggling with shop-owners, navigating around Changchun and crossing busy streets seemingly against all odds. “People there have a very different approach to obeying traffic laws,” said sophomore Chad Daniels. “Also, taking Chinese public transportation has totally redefined my understanding of ‘personal space’; entering and exiting buses and subways can sometimes literally mean climbing over 10 or so people.”

The program left room for the students to explore the city on their own and get to know some of the Russian and Korean students who shared their classroom, many of whom spoke English. Grant fondly remembers junior Nick Stefan challenging one of the many men who play Xiangqi, or “Chinese chess,” on the street to a game, and beating him. “I don’t usually play with the people on the street because it’s hard for me to beat them.” said Grant.  Each student took away valuable experiences that will be integrated into their course of study at Marlboro. For sophomore Megan Reed, experiencing the Chinese language on its own turf ties into her interest in language as a whole. “I’m studying theoretical linguistics, which looks past the basics of language and dives more directly into the foundation of all languages. So knowing more than one language can help to prove points in this field.”

Each student took away valuable experiences that will be integrated into their course of study at Marlboro. For sophomore Megan Reed, experiencing the Chinese language on its own turf ties into her interest in language as a whole. “I’m studying theoretical linguistics, which looks past the basics of language and dives more directly into the foundation of all languages. So knowing more than one language can help to prove points in this field.”

For junior Mike Ulen, who is interested in exploring Chinese folk crafts, especially woodworking, the trip helped put his Plan of Concentration into perspective. He said, “It enhanced my Chinese and made it easier to learn more about China via the vehicle of its own language, which is incredibly important.”

Students take performance off the hill

“I think having performances that celebrate, educate, question and inspire communities is critical to keeping those communities vibrant and alive,” said Jodi Clark ’95, assistant director of youth initiatives at Monadnock Family Services in Keene, New Hampshire. “All cultures I can think of have some means of performance that fulfills the need for these kinds of cultural reflections.” Jodi coordinates ActingOut, an issue-oriented teen theater program where three Marlboro students had internships this fall as part of a class called Community-Based Performance.

“Community-based performance challenges participants to immerse themselves in the communication of experience,” said Ken Schneck, dean of students, who taught the class. “This isn’t about boxing in the artist as a solitary genius, but is instead rooted in that which happens collectively: Individuals interact with a group of people with some shared identity, and this lived experience then informs the art, further developing the sense of community.”

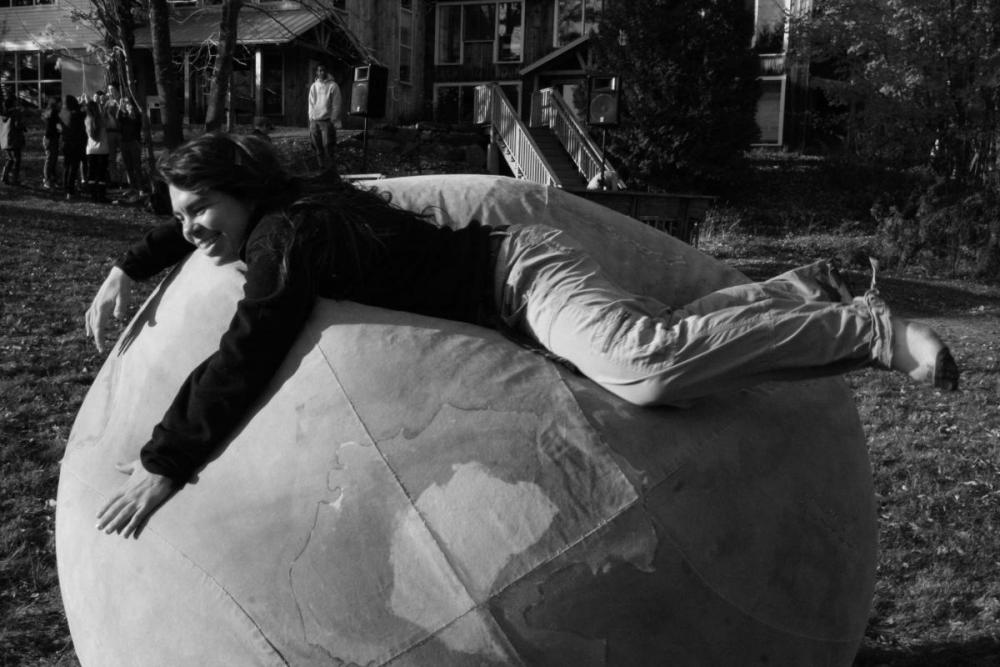

This was amply demonstrated by Kevin and Erin Maile O’Keefe, founders of CircusYoga, who worked with the class on community performance exercises they call “kinesthetic play.” Their collaboration with the students culminated with an evening of lively dancing in the streets of Brattleboro during the town’s “gallery walk,” where they invited other community members to join in.

“We like to find activities that kind of level the playing field,” said Erin. “It doesn’t matter what language you came into the world with, it doesn’t matter what your culture is, because together we’re going to co-create culture through play.”

In addition to ActingOut, students interned at Mahalo Art Center, the Theater Adventure Program (TAP) at New England Youth Theater, and Sandglass Theater, directed by former visiting faculty member Eric Bass.  “We walked in and were thrown into the fire right away,” said sophomore Samantha Hohl, who interned at TAP, a theater program for children, youth and adults with disabilities directed by Laura Lawson Tucker ’77. “We were amazed at how Laura can incorporate herself into everything and maintain control on so many levels. It works really well for how crazy it is.”

“We walked in and were thrown into the fire right away,” said sophomore Samantha Hohl, who interned at TAP, a theater program for children, youth and adults with disabilities directed by Laura Lawson Tucker ’77. “We were amazed at how Laura can incorporate herself into everything and maintain control on so many levels. It works really well for how crazy it is.”

“I think these internships will help students broaden their worldview beyond their studies and beyond ‘being on the hill,’” said Laura. “My hope is that they will go out into the world understanding how critical it is that the arts are offered within a community, in order to give all a voice, as well as the power of theater to strengthen and frame a community and its members.”

“Ken’s class provides such a rare opportunity to take advantage of this arts-rich region and to truly see some of the places where the strength of our greater Brattleboro area comes from,” said Jodi. “Having hands-on knowledge, observing or participating in these various community organizations, and feeling firsthand the power of their art is one of the best sorts of learning experiences.”

New faculty member broadens ceramics program

“I am on the cusp of changing my palette of glaze colors—I’m hunting for a good deep purple,” said Martina Lantin, Marlboro’s new ceramics professor. That’s not all that’s changing in the ceramics program, as Martina brings a refreshingly broad practice and perspective into the studio that fits in well with Marlboro’s visual arts program.

“I am on the cusp of changing my palette of glaze colors—I’m hunting for a good deep purple,” said Martina Lantin, Marlboro’s new ceramics professor. That’s not all that’s changing in the ceramics program, as Martina brings a refreshingly broad practice and perspective into the studio that fits in well with Marlboro’s visual arts program.

“In art there’s so much emphasis placed on the original idea, or the original work, that I think young people are often reluctant to look more broadly at what has come before,” said Martina. “I think it’s important to start training students to look at other work, and look at it critically: not just what this artist has done, but where their inspirations come from and whether their artist’s statement actually matches what they’ve achieved.” She knows that ceramics is about engaging one’s mind as well as one’s hands, and her classes incorporate research projects and critiques to establish each student’s own conceptual development and vocabulary.

“I see ceramics, and all art-making, as integral to a liberal arts curriculum,” said Martina. “Ceramics combines chemistry, physics and artistic expression, for example. It takes care and attention to craft, and the determination to develop skill is akin to learning the art of writing and critical thinking.”

Martina has an M.F.A. from Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University, but her knowledge of ceramics has been broadened by numerous international experiences, including an apprenticeship in England and graduate study in Denmark. She also worked as a production potter, and favorably compares the community environment at Marlboro to communal studios she has worked in. She likes that the individualized learning paradigm at Marlboro allows her to explore alongside her students.

As far as her own work, Martina draws inspiration from aspects of material culture and the story of how populations have moved around the globe through history. She has had shows across the United States and in Canada, and is represented in several galleries. In 2010 she received an artist fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission and was featured in the October issue of Ceramics Monthly.

“I am always striving to develop new forms in the studio, and have been fascinated with ‘flower bricks’ [vases that hold several separate stems] in the past year—they offer a unique connection to ceramic history as well as the dual potential of utilitarian and decorative functions.”

While the divide between functional and sculptural sometimes runs deep in the ceramics world, Martina is one of many modern ceramists who are challenging the centuries-old aesthetic that anything useful cannot also be beautiful. One of the things that attracted her to Marlboro was that the college was looking for a “vessel maker.” This implied a strong commitment to the craft tradition, or functional ceramics, which is uncommon in an art discipline dominated by sculptural ceramics.“I try to disengage from that professional debate of art versus craft,” said Martina. “In the same way that I see ceramics as just as academically rigorous as any other course here at Marlboro, I think ceramics is as aesthetically valid as any other form of visual art. It’s really exciting to know that functional ceramics is fostered and seen as being important here.”

Martina is enjoying working with the other visual arts faculty to integrate their curriculum and build on their mutual strengths, creating a diverse and dynamic program. “When I consider my colleagues Cathy Osman and Tim Segar and John Willis, I can imagine myself complementing their approach to teaching and individual aesthetics.”

To see more of Martina’s work, go to her website at www.mlceramics.com.

Events put the world on stage

Whittemore Theater was buzzing this fall with a variety of dramatic events, both homegrown and from afar, comic and tragic. In September, for a second year, the Marlboro community welcomed Castle Theatre Company, the official theater company of University College, Durham, in the United Kingdom. The company, composed of talented students and graduates of Durham, rendered Shakespeare’s dark tragedy known as “the Scottish play.”

Whittemore Theater was buzzing this fall with a variety of dramatic events, both homegrown and from afar, comic and tragic. In September, for a second year, the Marlboro community welcomed Castle Theatre Company, the official theater company of University College, Durham, in the United Kingdom. The company, composed of talented students and graduates of Durham, rendered Shakespeare’s dark tragedy known as “the Scottish play.”

“Castle Theatre brought us an engaging, focused, streamlined rendition of Macbeth, featuring bold interpretive edges and lucid performances,” said Paul Nelsen, theater professor. “These British students have taken a real interest in Marlboro as well, and our hosting them gives us a chance for an invigorating exchange.”

Another highlight in September was a performance in the biennial Puppets in the Green Mountains Festival, presented by Sandglass Theater. This year’s participant was Colette Garrigan, from Normandy, France, with an imaginative shadow puppet performance of personal narrative, called Sleeping Beauty. “Puppets in the Green Mountains Festival offers students an opportunity to encounter international artists who present work outside familiar notions of conventional theater,” said Paul.

In October, film and video professor Jay Craven presented “Queen City Radio Hour,” a live performance of original comedy and music, recorded for future broadcast over Vermont Public Radio. This third edition of the variety show featured performances by senior Heather Reed, Amber Schaefer ’10, Gahlord Dewald ’98 and visiting music professor Charlie Schneeweis. Comic sketches included “Slender Pickins Rural Dating and Mating Service,” “The In-Laws Holiday Travel Bureau” and purportedly the only Vermont gubernatorial debate to include the word “giblet.”

Over the course of the semester, guest director Anna Bean worked with a crew and cast of Marlboro students in an exploration of Sarah Ruhl’s contemporary play The Clean House, presented at Whittemore in November.

“The Clean House is a comedy driven by issues of class and race,” said Anna, who received her doctorate in performance studies from New York University and edited A Sourcebook on African-American Performance. She chose Ruhl’s work partly because women playwrights are typically underrepresented in both professional theater and college programs. The Clean House also challenges cultural and language barriers. “Casting a play at a small college with a mandatory requirement that two main actors speak Portuguese and Spanish was risky, but I believe the ‘risk’ was worth the result: a play that lives in several cultural worlds at the same time.”

With experience teaching at Williams College and Wesleyan University, Anna was not disappointed by the caliber of cast and crew she found at Marlboro. “Working with them all has been a true joy because I did not have to set high standards—they already have and meet them in their lives as Marlboro students,” she said. “With so many stellar students dedicated to making intellectually stimulating theater, I hope the theater program will continue to be supported in bringing guest artists and teachers to campus.”

For more information about events on campus, theatrical and otherwise, go to www.marlboro.edu/news/events.See excerpts from the October 10 piano recital by Cynthia Raim, the first in this year’s Music for a Sunday Afternoon concert series honoring retired music professor Luis Batlle, at www.youtube.com/watch?v=op24I8bs7yc.

In October, an exhibit of photos by Forrest Holzapfel (son of David ’72 and Michelle ’73) and a talk by the artist highlighted the residents of Marlboro and the role of photographers in documenting local history. The traveling exhibit, called “A Deep Look at a Small Town,” was supported by the Vermont Folklife Center.

In October, an exhibit of photos by Forrest Holzapfel (son of David ’72 and Michelle ’73) and a talk by the artist highlighted the residents of Marlboro and the role of photographers in documenting local history. The traveling exhibit, called “A Deep Look at a Small Town,” was supported by the Vermont Folklife Center.

Worthy of Note

“Marlboro students are the keenest students I’ve ever known,” said classics fellow Will Guast, who joined Marlboro in September. Will received his B.A. in classics from Christ Church, University of Oxford, receiving honors and prizes for Latin language, verse composition and historical linguistics. In addition to his background in languages, he is interested in examining religion in the Roman world, particularly during the transition from paganism to Christianity. “What excites me most about Marlboro is freedom,” said Will. “The freedom to take complete control of a subject and design my own courses totally from scratch; the free-thinking and diversity of the student body; and the freedom of being in the middle of the green mountains, with miles of trails and countryside to explore.” He plans to pursue postgraduate study in classics back at Oxford on the papyrology of the Second Sophistic.

“Marlboro students are the keenest students I’ve ever known,” said classics fellow Will Guast, who joined Marlboro in September. Will received his B.A. in classics from Christ Church, University of Oxford, receiving honors and prizes for Latin language, verse composition and historical linguistics. In addition to his background in languages, he is interested in examining religion in the Roman world, particularly during the transition from paganism to Christianity. “What excites me most about Marlboro is freedom,” said Will. “The freedom to take complete control of a subject and design my own courses totally from scratch; the free-thinking and diversity of the student body; and the freedom of being in the middle of the green mountains, with miles of trails and countryside to explore.” He plans to pursue postgraduate study in classics back at Oxford on the papyrology of the Second Sophistic.

Did you know that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students are two to three times more likely to use alcohol and other drugs than their straight counterparts? Neither did many college administrators before going to one of Ken Schneck’s talks at the regional conference of the National Association for Campus Activities. Ken was a featured speaker at the November conference, sharing the podium with other leaders in higher education administration. In addition to his talk, titled “Queers, Jeers and Beers,” Ken presented on creating programming for a new generation of students who expect administrators to know more than they usually do about LGBT students. “We spend so much time at these conferences focusing on LGBT 101, we lose sight of how some of the specific challenges faced by gay students directly result in increased risky behavior,” said Ken.  In August, Marlboro welcomed Yang “Louis” Liu, the new mathematics fellow. “The community here creates an excellent environment for teaching and learning,” said Louis, who received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Guangzhou University and his master’s from Sun Yat-sen University. He has been a teaching assistant at the University of Georgia, where he received his Ph.D. in mathematics in 2010, and a research assistant in both marine science and mathematics. Louis’ research focuses on random matrices and compressed sensing, but he is also interested in the mathematical modeling of aggregations of marine particles. “This is a great experience, teaching mathematics classes and advising students at Marlboro,” said Louis. “They are very self-motivated and have a breadth of knowledge across different disciplines.”

In August, Marlboro welcomed Yang “Louis” Liu, the new mathematics fellow. “The community here creates an excellent environment for teaching and learning,” said Louis, who received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Guangzhou University and his master’s from Sun Yat-sen University. He has been a teaching assistant at the University of Georgia, where he received his Ph.D. in mathematics in 2010, and a research assistant in both marine science and mathematics. Louis’ research focuses on random matrices and compressed sensing, but he is also interested in the mathematical modeling of aggregations of marine particles. “This is a great experience, teaching mathematics classes and advising students at Marlboro,” said Louis. “They are very self-motivated and have a breadth of knowledge across different disciplines.”

“I have long identified with the culture of ‘free inquiry’ associated with Marlboro College,” said Eileen Harney, who joined the college this fall as the Mellon Foundation–funded humanities fellow. “It is rewarding to be at an institution that promotes individuality and self-discovery among the student body while respecting and showing appreciation for the college’s own history.” Eileen received her B.A. in English from Boston College and her master’s and doctorate in medieval studies from the University of Toronto. Her interests in medieval literature and women’s and gender studies have guided her research on four female saints’ literary traditions across the medieval period. She has diverse experiences as a teacher, but finds the teaching expectations at Marlboro both challenging and exciting. “I am struck by how clearly invested Marlboro students are in their education,” Eileen said.

At the October meeting of the Consortium for Innovative Environments in Learning (CIEL), Sirkka Kaufman, assistant dean of academic affairs, participated in a panel discussion on applying results of the Wabash National Study of Liberal Arts Education. The Wabash study gathered evidence from dozens of institutions across the country to strengthen liberal arts education, but only a handful of those schools used innovative learning and assessment methods similar to Marlboro’s. Sirkka’s panel, which included presenters from New College of Florida, Alverno College, Prescott College and Hampshire College, described a data-sharing project using Wabash results to grapple with cross-institutional comparisons. “Our project stands to help put each institution’s learning outcomes into context and deepen our understanding of alternative practices and their likely effects,” said Sirkka. The panel conducted additional analyses prior to presenting again at the January meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. “Hornbills are uniquely tropical, uniquely visible even from a bike, and, well, just plain unique,” said Potash Hill editor Philip Johansson. His essay “Hornbills o’Plenty: Birdwatching by Bike in West Africa” was selected for inclusion in Wildbranch: An Anthology of Nature, Environmental and Place-based Writing, published by University of Utah press in 2010. The anthology is a collection of work from faculty and students of the Wildbranch Writing Workshop, held each summer for more than 20 years at Sterling College (current address of Will Wootton ’72, president), in Craftsbury, Vermont, and co-sponsored by Orion magazine. It also includes work of Alison Townsend ’75. “I take some credit for the success of the workshop because I attended the first one, I think, in 1988,” said Philip. “Hornbills o’Plenty” was based on his bicycle travels through Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali and Burkina Faso in 1993.

“Hornbills are uniquely tropical, uniquely visible even from a bike, and, well, just plain unique,” said Potash Hill editor Philip Johansson. His essay “Hornbills o’Plenty: Birdwatching by Bike in West Africa” was selected for inclusion in Wildbranch: An Anthology of Nature, Environmental and Place-based Writing, published by University of Utah press in 2010. The anthology is a collection of work from faculty and students of the Wildbranch Writing Workshop, held each summer for more than 20 years at Sterling College (current address of Will Wootton ’72, president), in Craftsbury, Vermont, and co-sponsored by Orion magazine. It also includes work of Alison Townsend ’75. “I take some credit for the success of the workshop because I attended the first one, I think, in 1988,” said Philip. “Hornbills o’Plenty” was based on his bicycle travels through Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali and Burkina Faso in 1993.

January marks the publication of retired literature professor Jaysinh Birjepatil’s new book, The Good Muslim of Jackson Heights, by Penguin (India). The fictional story of an aristocratic Muslim family that flees sectarian violence in their native central India, only to find reverberations in multiethnic urban America, Birje’s book traverses the tension between secular and religious. “Even though the central character in my book is a Muslim, I am not,” he said. “I was born in an upper caste Hindu family, but I lost all religion when I was packed off to a British boarding school in early childhood.” Birje says publication was delayed to assure that the book would not offend religious sensibilities, Muslim or Hindu. Meanwhile, Bennett & Spencer are publishing an American edition that will be available by the end of 2011.

Ayman Yacoub joined Marlboro this fall as a Fulbright-supported foreign language fellow, the fifth to continue the Arabic language program. “Being a fellow at Marlboro offers me the experience of a new culture and a different educational system,” said Ayman, who comes from Egypt. “Compared to other students I have had, Marlboro students enjoy their lives and find balance between their academic needs and their special interests.” He received his bachelor’s in English from Al-Azhar University in Cairo, and also studied English at American University in Cairo and educational translation at Al-Azhar University. Ayman has been a volunteer teacher at an orphanage and is interested in history and poetry. After his fellowship he hopes to pursue research in the area of translation studies.

Ayman Yacoub joined Marlboro this fall as a Fulbright-supported foreign language fellow, the fifth to continue the Arabic language program. “Being a fellow at Marlboro offers me the experience of a new culture and a different educational system,” said Ayman, who comes from Egypt. “Compared to other students I have had, Marlboro students enjoy their lives and find balance between their academic needs and their special interests.” He received his bachelor’s in English from Al-Azhar University in Cairo, and also studied English at American University in Cairo and educational translation at Al-Azhar University. Ayman has been a volunteer teacher at an orphanage and is interested in history and poetry. After his fellowship he hopes to pursue research in the area of translation studies.