Summer 2013

Editor’s Note

In her article on a rural retreat for intellectual luminaries of the 1930s, Kate Hollander ’02 notes that German tourists now wonder why Bertolt Brecht, “that sly and worldly poet of the cities, would spend six years in this former farmhouse on a Danish island.” Rural retreats are something Marlboro College students understand very well, and indeed many have had their own intellectual fires set ablaze on this rural, unpretentious campus. Few examples are as arresting as the case of Robert MacArthur ’51, whose meteoric rise, from skinning mammals in a former farmhouse called Mather House to pioneering new mathematical approaches to ecology, is charted in an article by Dan Toomey ’79 in the following pages.

This issue of Potash Hill brings you from the aftermath of conflict and violence in Guatemala, as reported by Chrissy Raudonis ’11, to the quiet, poignant poetry of Kimberly Cloutier Green ’78. We hear from math professor Matt Ollis about measuring campus sustainability, and from freshman Christian Lampart about theater professor Paul Nelsen’s big shoes to fill. As every summer, we celebrate the graduating students and their far-reaching and innovative Plans of Concentration.

If you have some reflection on your own humble roots at Marlboro, I encourage you to share them with us. You can read responses to the last issue of Potash Hill on the Letters page.

—Philip Johansson, editor

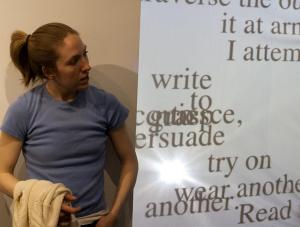

Front cover: “Diurne #9,” by Lila Kole-Berlingieri ’13, from her senior exhibit in the Drury Gallery this spring. Lila’s Plan of Concentration in literature and visual arts investigated the role of art and narrative, especially the works of Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf, in realizing selfhood. Photo by Dianna Noyes

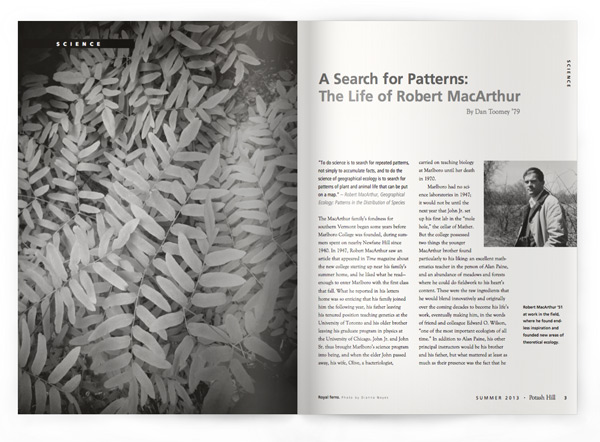

A Search for Patterns: The Life of Robert MacArthur

By Dan Toomey ’79

“To do science is to search for repeated patterns, not simply to accumulate facts, and to do the science of geographical ecology is to search for patterns of plant and animal life that can be put on a map.” – Robert MacArthur, Geographical Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Species

The MacArthur family’s fondness for southern Vermont began some years before Marlboro College was founded, during summers spent on nearby Newfane Hill since 1940. In 1947, Robert MacArthur saw an article that appeared in Time magazine about the new college starting up near his family’s summer home, and he liked what he read— enough to enter Marlboro with the first class that fall. What he reported in his letters home was so enticing that his family joined him the following year, his father leaving his tenured position teaching genetics at the University of Toronto and his older brother leaving his graduate program in physics at the University of Chicago. John Jr. and John Sr. thus brought Marlboro’s science program into being, and when the elder John passed away, his wife, Olive, a bacteriologist, carried on teaching biology at Marlboro until her death in 1970.

The MacArthur family’s fondness for southern Vermont began some years before Marlboro College was founded, during summers spent on nearby Newfane Hill since 1940. In 1947, Robert MacArthur saw an article that appeared in Time magazine about the new college starting up near his family’s summer home, and he liked what he read— enough to enter Marlboro with the first class that fall. What he reported in his letters home was so enticing that his family joined him the following year, his father leaving his tenured position teaching genetics at the University of Toronto and his older brother leaving his graduate program in physics at the University of Chicago. John Jr. and John Sr. thus brought Marlboro’s science program into being, and when the elder John passed away, his wife, Olive, a bacteriologist, carried on teaching biology at Marlboro until her death in 1970.

Marlboro had no science laboratories in 1947; it would not be until the next year that John Jr. set up his first lab in the “mole hole,” the cellar of Mather. But the college possessed two things the younger MacArthur brother found particularly to his liking: an excellent mathematics teacher in the person of Alan Paine, and an abundance of meadows and forests where he could do fieldwork to his heart’s content. These were the raw ingredients that he would blend innovatively and originally over the coming decades to become his life’s work, eventually making him, in the words of friend and colleague Edward O. Wilson, “one of the most important ecologists of all time.” In addition to Alan Paine, his other principal instructors would be his brother and his father, but what mattered at least as much as their presence was the fact that he could roam at will through fields and woods, honing his observation skills and thinking about what he observed.

Eccentricity at Marlboro, then as now, was not only tolerated but to a degree encouraged, especially if it was exhibited within the context of the pursuit of knowledge. Robert MacArthur’s penchant for trapping small animals in the woods around the college and skinning them in his dormitory room is one such example. His two roommates in Mather, the men’s dormitory at the time, accepted this behavior more or less unconditionally at first. But one day he returned carrying by the tail a specimen of Mephitis mephitis (Latin for “noxious odor, noxious odor”), with every intention of skinning it within the close confines of the shared room. The roommates’ tolerance for eccentricity had finally reached its limit, and Robert was compelled to move his clothes, belongings, and skunk carcass to a sugar shack near where the science building now stands. There he lived contentedly for the remainder of that semester, carrying out his taxonomic studies without interference.

Eccentricity at Marlboro, then as now, was not only tolerated but to a degree encouraged, especially if it was exhibited within the context of the pursuit of knowledge. Robert MacArthur’s penchant for trapping small animals in the woods around the college and skinning them in his dormitory room is one such example. His two roommates in Mather, the men’s dormitory at the time, accepted this behavior more or less unconditionally at first. But one day he returned carrying by the tail a specimen of Mephitis mephitis (Latin for “noxious odor, noxious odor”), with every intention of skinning it within the close confines of the shared room. The roommates’ tolerance for eccentricity had finally reached its limit, and Robert was compelled to move his clothes, belongings, and skunk carcass to a sugar shack near where the science building now stands. There he lived contentedly for the remainder of that semester, carrying out his taxonomic studies without interference.

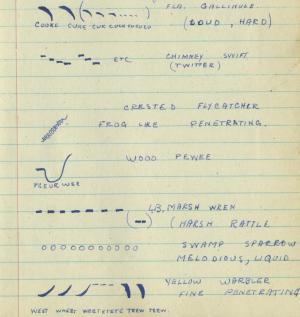

After graduating with highest honors in 1951, Robert earned an M.S. in mathematics from Brown University, then went on to the doctoral program in biology at Yale. His dissertation paper broke new ground in the field of for community ecology, introducing the idea of mathematical “niche apportionment models.” He showed that five different species of wood warblers, apparently occupying the same niche, actually hunted for their food in five different portions of the same tree. Building on this idea during a subsequent year at Oxford, he developed the “broken stick model,” theorizing that competing bird species were able to co-exist in a community by dividing the resources so that each used different portions of the niche, like pieces of a stick.

Robert returned to the United States to his first teaching appointment, at the University of Pennsylvania. He continued to publish papers that demonstrated his ability to interpret mathematically what he so keenly observed in the natural world, and in so doing pushed the field of ecology in new directions. One such study, published in Ecology by Robert and brother John, involved fieldwork at 13 different sites (one of which was a field abutting Marlboro College property) from Panama to Maine. To measure something they called “foliage height diversity,” they mounted a white board on a pole and held it aloft at each site. They then measured how far from a tree the board had to be, at different heights, for half of it to be obscured by vegetation. And they listened and watched for birds to determine how diverse the local bird community was.

“I was the one who would climb up the tree, because I was more comfortable with that,” said John, who retired in 1989 but continues to teach a class at Marlboro each year to this day. “Sometimes I laughed so hard I would almost fall out of the tree, watching Robert try to back through the for est with this pole high in the dense foliage.” What they discovered, by way of patient field observation, bird-listening, and the application of mathematical equations, was that bird species diversity could be predicted by the degree of foliage height diversity: from Panama to Maine, across many kinds of deciduous forests, the more foliage at different heights, the more species of birds can be found.

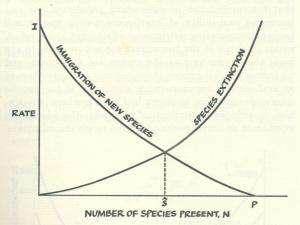

In 1965 Robert left the University of Pennsylvania to take a position at Princeton. Shortly thereafter he wrote, with Edward O. Wilson, The Theory of Island Biogeography. Its core idea was that the number of species on an island, or any isolated habitat, is determined by the balance between immigration and extinction. The increasing number of citations the book accrued each year from its publication (when it was cited five times) through 1982 (when it peaked at 161 times) is solid confirmation that MacArthur and Wilson’s theory had become, in the words of science writer David Quammen, “one of the central paradigms of ecology.” Their basic understanding of the dynamics of isolated populations continues to inform conservation science, as researchers look for ways to address the accelerating fragmentation and separation of ecosystems brought about by human activity.

In 1965 Robert left the University of Pennsylvania to take a position at Princeton. Shortly thereafter he wrote, with Edward O. Wilson, The Theory of Island Biogeography. Its core idea was that the number of species on an island, or any isolated habitat, is determined by the balance between immigration and extinction. The increasing number of citations the book accrued each year from its publication (when it was cited five times) through 1982 (when it peaked at 161 times) is solid confirmation that MacArthur and Wilson’s theory had become, in the words of science writer David Quammen, “one of the central paradigms of ecology.” Their basic understanding of the dynamics of isolated populations continues to inform conservation science, as researchers look for ways to address the accelerating fragmentation and separation of ecosystems brought about by human activity.

In 1968 Robert was appointed Henry Fairfield Osborn Professor of Biology at Princeton. That same year he developed the “species packing” hypothesis, which argued that the number of species in a habitat is limited by the number of niches those species can potentially occupy. This suggested of course that elements of an ecosystem could be altered to attract additional desired species, a foundational premise of conservation biology today and of the movement for ecological restoration worldwide.

Robert’s decision to write Geographical Ecology, his final book, was spurred by the sobering news in 1971 that he had an incurable cancer. He wrote the book longhand “with no access to libraries, entirely from memory” at the family cabin on the shore of South Pond, Marlboro. He was dying, and the time remaining to collect all of his interrelated ideas under a single cover was short. Helping him were wife Betsy—who had a degree in botany—and brother John, both of whom suggested improvements to some of the chapters. Betsy typed the final manuscript. Robert called the book’s organization “phenomenological,” by which he meant that it articulated the ways in which empirical observations of phenomena are interrelated. Its prose style, as one might expect, reflects the exactitude, lucidity, and density of mathematics. The book completed, he died at the age of 42, leaving behind a remarkable legacy.

Robert’s decision to write Geographical Ecology, his final book, was spurred by the sobering news in 1971 that he had an incurable cancer. He wrote the book longhand “with no access to libraries, entirely from memory” at the family cabin on the shore of South Pond, Marlboro. He was dying, and the time remaining to collect all of his interrelated ideas under a single cover was short. Helping him were wife Betsy—who had a degree in botany—and brother John, both of whom suggested improvements to some of the chapters. Betsy typed the final manuscript. Robert called the book’s organization “phenomenological,” by which he meant that it articulated the ways in which empirical observations of phenomena are interrelated. Its prose style, as one might expect, reflects the exactitude, lucidity, and density of mathematics. The book completed, he died at the age of 42, leaving behind a remarkable legacy.

Robert once confided to Edward O. Wilson that he would “rather save an endangered habitat than create an important scientific theory.” Yet he did in fact author several important scientific theories that, since his death 40 years ago, have stood as the foundation of a profusion of research done by those who have succeeded him. This research has in turn helped preserve or restore endangered habitats in many places on the globe.

Asked once to define religion, John MacArthur responded, “The fascination with the fact that nature is so regular.” It was the regularity, or patterning, in nature that so fascinated his brother—the silhouette of foliage against a white board, for example, that coincided with the varying harmonics of birdsong heard in that same foliage. From out of this convergence of visual and aural patterns emerged other patterns that could be discerned only by a gifted mathematical imagination. Robert MacArthur saw an unmistakable beauty in patterns, both seen and imagined, over the course of his life. He said as much on the first page of his final book:

Asked once to define religion, John MacArthur responded, “The fascination with the fact that nature is so regular.” It was the regularity, or patterning, in nature that so fascinated his brother—the silhouette of foliage against a white board, for example, that coincided with the varying harmonics of birdsong heard in that same foliage. From out of this convergence of visual and aural patterns emerged other patterns that could be discerned only by a gifted mathematical imagination. Robert MacArthur saw an unmistakable beauty in patterns, both seen and imagined, over the course of his life. He said as much on the first page of his final book:

Doing science is not such a barrier to feeling or such a dehumanizing influence as is often made out. It does not take the beauty from nature. The only rules of scientific method are honest observations and accurate logic. To be great science it must also be guided by a judgment, almost an instinct, for what is worth studying. No one should feel that honesty and accuracy guided by imagination have any power to take away nature’s beauty.

One might go further to assert that in fact “doing science” actually begins with recognition of the beauty of the natural world and the embracing of it, and then asking informed and imaginative questions about what is observed. “Honesty and accuracy guided by imagination” in the pursuit of beauty is an accurate summation of Robert MacArthur’s life, a life that those of us who care about the future of the earth need to be profoundly grateful for.

Dan Toomey teaches writing and English at Landmark College, and has contributed many great articles to Potash Hill, most recently in the Winter- Spring 2007 issue. The MacArthur Prize was established in 1973 in memory of Robert MacArthur, then rededicated to his whole family for their positive impact on the science program at Marlboro College.

Ode to Evolution

Another well-known and fairly influential scientist was Charles Darwin, who turned the Victorian world upside down with his theory of evolution by natural selection. Nikki Haug ’13 did her Plan of Concentration on the ripples of Darwin’s theory through literature, specifically the poetry of Robert Browning and Lord Alfred Tennyson. “What separated Darwin from other materialist thinkers, both before and during his time, was how much information he managed to synthesize,” said Nikki. “Darwin took what had previously been philosophical and placed it into a naturalist’s perspective, turning materialist views from opinions into facts.” She explored how Victorians, including Victorian poets, were forced to consider the idea that humanity was not distinguished from other animals and could be surpassed by a more perfect race.

Another well-known and fairly influential scientist was Charles Darwin, who turned the Victorian world upside down with his theory of evolution by natural selection. Nikki Haug ’13 did her Plan of Concentration on the ripples of Darwin’s theory through literature, specifically the poetry of Robert Browning and Lord Alfred Tennyson. “What separated Darwin from other materialist thinkers, both before and during his time, was how much information he managed to synthesize,” said Nikki. “Darwin took what had previously been philosophical and placed it into a naturalist’s perspective, turning materialist views from opinions into facts.” She explored how Victorians, including Victorian poets, were forced to consider the idea that humanity was not distinguished from other animals and could be surpassed by a more perfect race.

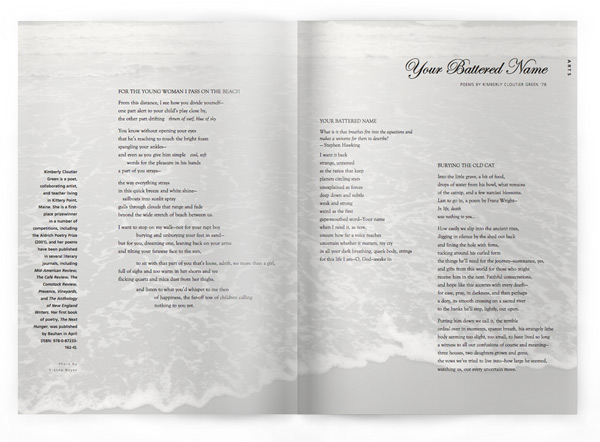

Your Battered Name

Poems by Kimberly Cloutier Green ’78

For the Young Woman I Pass on the Beach

From this distance, I see how you divide yourself—

one part alert to your child’s play close by,

the other part drifting thrum of surf, blue of sky=

You know without opening your eyes

that he’s reaching to touch the bright foam

spangling your ankles—

and even as you give him simple cool, soft

words for the pleasure in his hands

a part of you strays—

the way everything strays

in this quick breeze and white shine—

sailboats into sunlit spray

gulls through clouds that range and fade

beyond the wide stretch of beach between us.

I want to stop on my walk—not for your rapt boy

burying and unburying your feet in sand—

but for you, dreaming one, leaning back on your arms

and tilting your faraway face to the sun,

to sit with that part of you that’s loose, adrift, no more than a girl,

full of sighs and too warm in her shorts and tee

flicking quartz and mica dust from her thighs,

and listen to what you’d whisper to me then

of happiness, the far-off tow of children calling

nothing to you yet.

Your Battered Name

What is it that breathes fire into the equations and

makes a universe for them to describe?

— Stephen Hawking

I want it back

strange, untamed

as the ratios that keep

planets circling stars

unexplained as forces

deep down and subtle

weak and strong

weird as the first

gape-mouthed word—Your name

when I need it, as now,

unsure how far a voice reaches

uncertain whether it matters, my cry

in all your dark breathing, quark body, strings

for this life I am—O, God—awake in

Burying the Old Cat

Into the little grave, a bit of food,

drops of water from his bowl, what remains

of the catnip, and a few narcissi blossoms.

Last to go in, a poem by Franz Wright—

In life, death

was nothing to you…

How easily we slip into the ancient rites,

digging in silence by the shed out back

and lining the hole with ferns,

tucking around his curled form

the things he’ll need for the journey—sustenance, yes,

and gifts from this world for those who might

receive him in the next. Faithful consecrations,

and hope like this accretes with every death—

for ease, pray, in darkness, and then perhaps

a dory, its smooth crossing on a sacred river

to the banks he’ll step, lightly, out upon.

Putting him down we call it, the terrible

ordeal over in moments, sparest breath, his strangely lithe

body seeming too slight, too small, to have lived so long

a witness to all our confusions of course and meaning—

three houses, two daughters grown and gone.

the vows we’ve tried to live into—how large he seemed,

watching us, our every uncertain move.

Kimberly Cloutier Green is a poet, collaborating artist, and teacher living in Kittery Point, Maine. She is a firstplace prizewinner in a number of competitions, including the Aldrich Poetry Prize (2001), and her poems have been published in several literary journals, including Mid-American Review, The Café Review, The Comstock Review, Presence, Vineyards, and The Anthology of New England Writers. Her first book of poetry, The Next Hunger, was published by Bauhan in April (ISBN: 978-0-87233- 162-4).

Kimberly Cloutier Green is a poet, collaborating artist, and teacher living in Kittery Point, Maine. She is a firstplace prizewinner in a number of competitions, including the Aldrich Poetry Prize (2001), and her poems have been published in several literary journals, including Mid-American Review, The Café Review, The Comstock Review, Presence, Vineyards, and The Anthology of New England Writers. Her first book of poetry, The Next Hunger, was published by Bauhan in April (ISBN: 978-0-87233- 162-4).

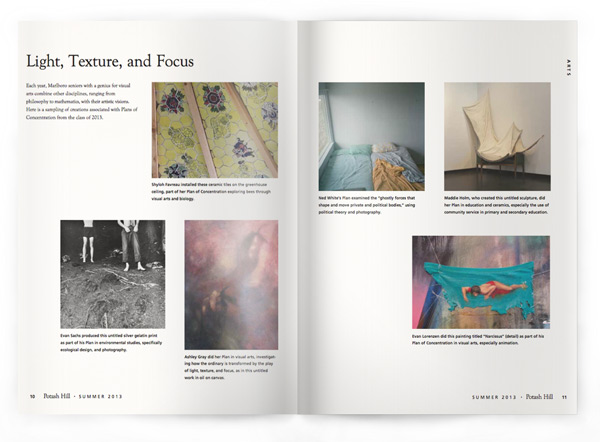

Light, Texture, and Focus

Each year, Marlboro seniors with a genius for visual arts combine other disciplines, ranging from philosophy to mathematics, with their artistic visions. Here is a sampling of creations associated with Plans of Concentration from the class of 2013.

Ashley Gray did her Plan in visual arts, investigating how the ordinary is transformed by the play of light, texture, and focus, as in this untitled work in oil on canvas.

Evan Sachs produced this untitled silver gelatin print as part of his Plan in environmental studies, specifically ecological design, and photography.

Evan Sachs produced this untitled silver gelatin print as part of his Plan in environmental studies, specifically ecological design, and photography.

Shyloh Favreau installed these ceramic tiles on the greenhouse ceiling, part of her Plan of Concentration exploring bees through visual arts and biology.

Shyloh Favreau installed these ceramic tiles on the greenhouse ceiling, part of her Plan of Concentration exploring bees through visual arts and biology.

Ned White’s Plan examined the “ghostly forces that shape and move private and political bodies,” using political theory and photography.

Ned White’s Plan examined the “ghostly forces that shape and move private and political bodies,” using political theory and photography.

Maddie Holm, who created this untitled sculpture, did her Plan in education and ceramics, especially the use of community service in primary and secondary education.

Maddie Holm, who created this untitled sculpture, did her Plan in education and ceramics, especially the use of community service in primary and secondary education.

Evan Lorenzen did this painting titled “Narcissus” (detail) as part of his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, especially animation.

Evan Lorenzen did this painting titled “Narcissus” (detail) as part of his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, especially animation.

House of Straw and Wind: Exile in Southern Denmark

By Kate Hollander '02

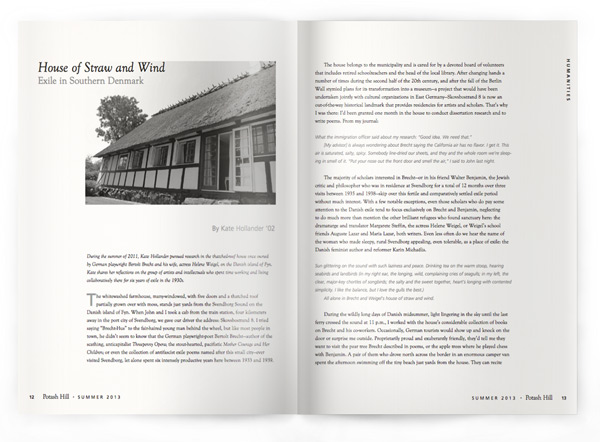

During the summer of 2011, Kate Hollander pursued research in the thatched-roof house once owned by German playwright Bertolt Brecht and his wife, actress Helene Weigel, on the Danish island of Fyn. Kate shares her reflections on the group of artists and intellectuals who spent time working and living collaboratively there for six years of exile in the 1930s.

The whitewashed farmhouse, many-windowed, with five doors and a thatched roof partially grown over with moss, stands just yards from the Svendborg Sound on the Danish island of Fyn. When John and I took a cab from the train station, four kilometers away in the port city of Svendborg, we gave our driver the address: Skovsbostrand 8. I tried saying “Brecht-Hus” to the fair-haired young man behind the wheel, but like most people in town, he didn’t seem to know that the German playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht—author of the scathing, anticapitalist Threepenny Opera; the stout-hearted, pacifistic Mother Courage and Her Children; or even the collection of antifascist exile poems named after this small city—ever visited Svendborg, let alone spent six intensely productive years here between 1933 and 1939.

The whitewashed farmhouse, many-windowed, with five doors and a thatched roof partially grown over with moss, stands just yards from the Svendborg Sound on the Danish island of Fyn. When John and I took a cab from the train station, four kilometers away in the port city of Svendborg, we gave our driver the address: Skovsbostrand 8. I tried saying “Brecht-Hus” to the fair-haired young man behind the wheel, but like most people in town, he didn’t seem to know that the German playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht—author of the scathing, anticapitalist Threepenny Opera; the stout-hearted, pacifistic Mother Courage and Her Children; or even the collection of antifascist exile poems named after this small city—ever visited Svendborg, let alone spent six intensely productive years here between 1933 and 1939.

The house belongs to the municipality and is cared for by a devoted board of volunteers that includes retired schoolteachers and the head of the local library. After changing hands a number of times during the second half of the 20th century, and after the fall of the Berlin Wall stymied plans for its transformation into a museum—a project that would have been undertaken jointly with cultural organizations in East Germany—Skovsbostrand 8 is now an out-of-the-way historical landmark that provides residencies for artists and scholars. That’s why I was there: I’d been granted one month in the house to conduct dissertation research and to write poems. From my journal:

What the immigration officer said about my research: “Good idea. We need that.”

[My advisor] is always wondering about Brecht saying the California air has no flavor. I get it. This air is saturated, salty, spicy. Somebody line-dried our sheets, and they and the whole room we’re sleeping in smell of it. “Put your nose out the front door and smell the air,” I said to John last night.

The majority of scholars interested in Brecht—or in his friend Walter Benjamin, the Jewish critic and philosopher who was in residence at Svendborg for a total of 12 months over three visits between 1935 and 1938—skip over this fertile and comparatively settled exile period without much interest. With a few notable exceptions, even those scholars who do pay some attention to the Danish exile tend to focus exclusively on Brecht and Benjamin, neglecting to do much more than mention the other brilliant refugees who found sanctuary here: the dramaturge and translator Margarete Steffin, the actress Helene Weigel, or Weigel’s school friends Auguste Lazar and Maria Lazar, both writers. Even less often do we hear the name of the woman who made sleepy, rural Svendborg appealing, even tolerable, as a place of exile: the Danish feminist author and reformer Karin Michaëlis.

Sun glittering on the sound with such laziness and peace. Drinking tea on the warm stoop, hearing seabirds and landbirds (in my right ear, the longing, wild, complaining cries of seagulls; in my left, the clear, major-key chortles of songbirds; the salty and the sweet together, heart’s longing with contented simplicity. I like the balance, but I love the gulls the best.)

Sun glittering on the sound with such laziness and peace. Drinking tea on the warm stoop, hearing seabirds and landbirds (in my right ear, the longing, wild, complaining cries of seagulls; in my left, the clear, major-key chortles of songbirds; the salty and the sweet together, heart’s longing with contented simplicity. I like the balance, but I love the gulls the best.)

All alone in Brecht and Weigel’s house of straw and wind.

During the wildly long days of Danish midsummer, light lingering in the sky until the last ferry crossed the sound at 11 p.m., I worked with the house’s considerable collection of books on Brecht and his co-workers. Occasionally, German tourists would show up and knock on the door or surprise me outside. Proprietarily proud and exuberantly friendly, they’d tell me they want to visit the pear tree Brecht described in poems, or the apple trees where he played chess with Benjamin. A pair of them who drove north across the border in an enormous camper van spent the afternoon swimming off the tiny beach just yards from the house. They can recite poems from Brecht’s volume Svendborger Gedichte, “Svendborg Poems,” which describe this house as a place of profound but uneasy refuge. They wonder why Brecht, that sly and worldly poet of the cities, would spend six years in this former farmhouse on a Danish island.

Their English is good and my German is fair, but I don’t get around to telling them that the answer to their question lies in Vienna, where Michaëlis, author of the controversial novel The Dangerous Age, taught at an extraordinary school—a school whose list of teachers and graduates included some of the great artists and thinkers of Central Europe, including one with whom the Marlboro community will be familiar: Ruldof Serkin. Michaëlis became a mentor to the aspiring young actress Helene Weigel through this school, and years later it was to Michaëlis’s house on the tiny island of Thurø that Weigel and Brecht first came in flight from Germany following Hitler’s rise to power. With funds lent by Michaëlis herself, Brecht and Weigel purchased the thatched-roof house at Skovsbostrand 8. You don’t hear the name Karin Michaëlis very much these days, but in Southern Fyn, it’s everywhere.

The museum is the only remaining “work house” in Scandinavia. You buy tickets and you go in and see what a miserable, horrible place it was and how everyone suffered before the welfare state. I wander around for a while trying to find the archives. Eventually I see a little map, go back around the side (for the second time), open the door...nobody in sight...ring the bell...a woman comes. Yes, it is the archives. Hanne will help me.

Hanne comes. She is a very nice energetic archive lady. At first she tells me she doesn’t have anything for me...the library archive would have it...or this other archive that covers the part of Svendborg the house is in. Then I see she has a calendar with a picture of KM. “Karin Michaëlis!” I say. “I am also studying her.” Oh! Well, now she might have things for me... she calls in another woman, also named Hanne. They scurry around. Yes, they have something. A whole file on the Brecht house. Another on KM. They show me into the big reading room...long table, handsome and homey.

They give me some gloves so I can look at some photos of Michaëlis at her house, Torrelore. She has great hats in every photo. I say I like her hats. Hanne says, “She was a very special lady.” There is such warmth here when anyone speaks about her. But, they all insist, she isn’t known in Denmark now.

The spring before I came to Svendborg, I was in touch with members of the Karin Michaëlis Society, which includes scholars and amateurs interested in her work and life. While at Skovsbostrand 8, three of them come to visit. I provide tea and miserable biscuits that I ruin through my inexperience with baking by weight and miscalculating temperatures in Celsius. They arrive with their arms full of things for me, whom they’ve never met: a huge bag of beautiful breads from a bakery on Thurø, a big tub of home-grown red currants, articles to read, a book. Languages fly: German, English, Danish, even Swedish, as we struggle to communicate, share, and read out loud to one another. Before they leave, they hug me tight. I’m almost undone by their kindness and generosity, which they insist is in the spirit of the selfless-to-afault Michaëlis herself. In tears as they drive away, I feel sure I’ve been touched, through them, by her warm and giving spirit.

Lightning over the ocean last night, and wind and rain. I feel safe in this little house, even with its five doors for escaping through.

A thatched roof is just as good as any other at keeping the rain out. This became obvious to me when a storm parked just off the coast for 72 hours toward the end of July; the rain lashed and the wind was so strong I could barely push open the door to go outside. But only the first inch or two of the reeds that make up the roof were soaked through; the rest of the thatch was totally dry.

A thatched roof needs to be replaced every 50 years or so. These days, historiographies last a much shorter time—and that’s probably not a bad thing. In the 60 years since Brecht’s death, scholars have understood him in an ever-evolving variety of ways: first as a solitary (if philandering) genius, then as an exploiter of women and even a plagiarist, and finally as the vital but not dominating center of a series of collaborative circles. I’m hoping to go a step further by showing how this particular community of artists, intellectuals, and socialists actually worked together in exile. The house at Skovsbostrand 8 is at the heart of that—reminding us that even great intellectuals have material needs for shelter, nourishment, and comfort. More than just a place of refuge, this house was a laboratory for artistic and intellectual collaboration, a place where various and sometimes contradictory ideas of socialism came into contact with the necessities of exile.

A Ph.D. candidate in modern European history at Boston University as well as a published poet, Kate Hollander is writing her dissertation on the artists and intellectuals who gathered at Skovsbostrand 8. She lives in Boston with John Coakley ’02.

Escaping to Home

“It is easy to spend a lot of time alone in the woods with oneself. It is truly hard to be alone with other people,” said Dane Fredericks ‘13, who did his Plan of Concentration on the theme of escape in American literature, focusing on Mark Twain, Flannery O’Conner, and Cormac McCarthy. His independent study was an essay based on a hitchhiking trip he took over winter break, comprising an oral history of the people he met. “I think that I made most of the people I encountered a little bit uncomfortable. Certainly they often made me uncomfortable,” said Dane, who learned as much about himself as his subjects. “I discovered that all the best stories came when I stopped trying to be someplace else and admitted that I wanted to be home. Home anywhere.”

“It is easy to spend a lot of time alone in the woods with oneself. It is truly hard to be alone with other people,” said Dane Fredericks ‘13, who did his Plan of Concentration on the theme of escape in American literature, focusing on Mark Twain, Flannery O’Conner, and Cormac McCarthy. His independent study was an essay based on a hitchhiking trip he took over winter break, comprising an oral history of the people he met. “I think that I made most of the people I encountered a little bit uncomfortable. Certainly they often made me uncomfortable,” said Dane, who learned as much about himself as his subjects. “I discovered that all the best stories came when I stopped trying to be someplace else and admitted that I wanted to be home. Home anywhere.”

Justice and Truth in the Ixil Region

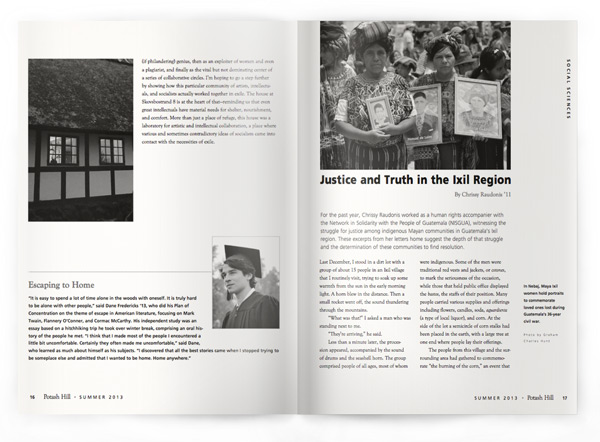

By Chrissy Raudonis ’11

For the past year, Chrissy Raudonis worked as a human rights accompanier with the Network in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala (NISGUA), witnessing the struggle for justice among indigenous Mayan communities in Guatemala’s Ixil region. These excerpts from her letters home suggest the depth of that struggle and the determination of these communities to find resolution.

Last December, I stood in a dirt lot with a group of about 15 people in an Ixil village that I routinely visit, trying to soak up some warmth from the sun in the early morning light. A horn blew in the distance. Then a small rocket went off, the sound thundering through the mountains.

Last December, I stood in a dirt lot with a group of about 15 people in an Ixil village that I routinely visit, trying to soak up some warmth from the sun in the early morning light. A horn blew in the distance. Then a small rocket went off, the sound thundering through the mountains.

“What was that?” I asked a man who was standing next to me.

“They’re arriving,” he said.

Less than a minute later, the procession appeared, accompanied by the sound of drums and the seashell horn. The group comprised people of all ages, most of whom were indigenous. Some of the men wore traditional red vests and jackets, or cotones, to mark the seriousness of the occasion, while those that held public office displayed the bastos, the staffs of their position. Many people carried various supplies and offerings including flowers, candles, soda, aguardiente (a type of local liquor), and corn. At the side of the lot a semicircle of corn stalks had been placed in the earth, with a large tree at one end where people lay their offerings.

The people from this village and the surrounding area had gathered to commemorate “the burning of the corn,” an event that occurred during Guatemala’s decades of internal armed conflict. One day in 1982, the army arrived with several hundred Ixil Self-Defense Civil Patrol (PAC) members, with orders to gather all of the corn that was drying in the fields awaiting the harvest. The army explained to the PAC members that they were going to distribute the corn to the communities. The PAC members spent the day gathering all the corn in the area, including part of the harvest of several other villages, and dumping it in the lot, forming a gigantic pile.

When the work was done, instead of distributing the food, the soldiers burned the whole heap, throwing the villagers’ clothes on top, including the women’s traditional, handmade huipiles and red cortes: their shirts and skirts. Witnesses from a village in the valley below, miles away, were able to see the giant “volcano of corn.” Sadly, the harvest was not the only loss of the day. The soldiers also threw several people on the fire alive, including a blind, elderly woman. The loss of life, and of the harvest, was devastating for the close-knit community of subsistence farmers for whom corn is sacred. Culturally, the burning of the corn was an unthinkable act.

To remember the past and beg forgiveness for the destruction of the harvest, Mayan priests lit a ceremonial fire. Participants watched and prayed toward the four directions. The air was full of the fragrance of smoke, the sound of the drums and chirmiria (a wind instrument), and occasional rockets, whose white tails marked the cloudless, blue sky. At one point, a man approached my partner and me. In the palm of his hand were the charred remains of corn kernels that he had found by digging a little in the dirt. It was powerful to witness the physical remains of the event, still present in the ground, decades later.

During Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war, which ended in 1996, this region was called the “Ixil Triangle” by the military. It was the site of severe civilian repression and control through military checkpoints, the concentration of populations in model villages, and coerced inscription in armed civilian patrol groups. The conflict resulted in the massacres of civilians by the army and the displacement of entire communities.

During Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war, which ended in 1996, this region was called the “Ixil Triangle” by the military. It was the site of severe civilian repression and control through military checkpoints, the concentration of populations in model villages, and coerced inscription in armed civilian patrol groups. The conflict resulted in the massacres of civilians by the army and the displacement of entire communities.

My work in the region is greatly tied to this history, although the specifics of my day-to-day activities vary. Some days I spend in different communities, visiting witnesses in genocide cases. While accompaniment work hopes to dissuade attacks and threats against those who are accompanied, there is also a strong element of solidarity in my interactions with many of the people that I visit. I talk with villagers about their children, their crops, and the local community to try to show that they are not alone in the huge and confusing process that is the search for justice and truth in Guatemala. Other days I spend accompanying meetings with witnesses and the organizations that represent them and with groups that are fighting to keep the control of land and natural resources in the hands of the local communities.

My first visit to a community showed me how the conflict has influenced people’s perspectives and how the logic of resistance and survival is very different from what I’m accustomed to. This particular community is small and fairly isolated—three hours by bus from the the closest town with police and government offices. The village has no electricity or running water. A single, wide dirt road connects it to other towns.

My first visit to a community showed me how the conflict has influenced people’s perspectives and how the logic of resistance and survival is very different from what I’m accustomed to. This particular community is small and fairly isolated—three hours by bus from the the closest town with police and government offices. The village has no electricity or running water. A single, wide dirt road connects it to other towns.

During the evening, I was sitting in a wooden chair next to a cook fire in the house I was staying in, drinking coffee with my partner and the woman who was hosting us. At one point, the woman started to talk about the war and mentioned some of the violence and hardships that the townspeople suffered. She briefly told us about the soldiers coming to the town and killing villagers. But what she wanted to talk about was her worry that it would happen again. She pointed toward the road and explained that this road would make it easy for the army to come back anytime it wanted to. As my partner tried to reassure her as best she could, I found myself considering a whole different perspective.

A lot of people that I’ve met in Guatemala have talked about the need for more development and less isolated villages. This was my first time hearing the concern that being connected and accessible would also make the population more vulnerable. Something as simple as a dirt road can be a source of worry, especially for those who are still traumatized by their war experiences.

Unfortunately, such worries are not unfounded. The country is becoming increasingly militarized in some areas, with the stated purpose of fighting drug trafficking. However, in most cases the militarized areas are also rich in natural resources, and many people see the increase in military outposts and bases as a means of providing economic security to investors rather than protecting the nation. The state of siege imposed on the town of Barillas last May and the massacre of seven peaceful protesters by soldiers in Totonicapan in October show that the government is also disposed to use its military power to control the civilian population.

Although most of the land in the Ixil region has relatively low agricultural potential, the area’s mineral wealth and abundance of rivers make it a popular site for mining and hydroelectric projects. Conflicts over land and natural resources are widespread through the region and often affect my work as an accompanier.

Although most of the land in the Ixil region has relatively low agricultural potential, the area’s mineral wealth and abundance of rivers make it a popular site for mining and hydroelectric projects. Conflicts over land and natural resources are widespread through the region and often affect my work as an accompanier.

For example, one community that I visit sits high up in the mountains, just under a forested ridgeline. From the road that goes through the town, I can look out over the valley below, bounded by a parallel ridge. The vista is patterned with cornfields, forests, and towns that are connected by winding dirt roads. The village is picturesque, with its expansive green fields full of grazing sheep backdropped by distant mountains, but I keep my camera in my bag. The tranquil-seeming setting is of great interest to a Mexican oil company that hopes to extract barite, an important mineral in the oil drilling process.

When my partner and I leave the community, we go by the main road, even though we know that there is a shorter and reportedly very pretty path that can also take us to our next destination. As outsiders, we have to tread with caution, because local residents are highly concerned about company employees entering their territory. One man from the area explained to me that the community isn’t against development in and of itself. They want development, but a development that comes from within the community and benefits the community. While this village has managed to keep land ownership in the hands of local residents, others are less fortunate and find themselves with less leverage against the interlocked interests of corporations and the national government.

The process of losing local control over land is closely tied to the internal armed conflict. In 1984, in the middle of the violence, the government nationalized over 3,800 acres of land in one town, without notifying the local population. It wasn’t until a few years ago that the community discovered they were no longer the owners of their communal land, or ejido, when a government employee let the information slip.

During June and July, my partner and I accompanied meetings convened by a collective called Resistencia de los Pueblos (Resistance of the People), which were intended to inform villagers about what had happened to their land and the future plans of mining and hydroelectric companies in the area. Land security and environmental quality are of the utmost importance to the local people, who depend on subsistence agriculture for a large part of their livelihood. As one member of the collective explained to a group, “It’s a sin to not defend the land, because without land we don’t have life.”

Chrissy Raudonis graduated from the World Studies Program with a Plan of Concentration in environmental studies and Spanish, focusing on social and environmental issues around mining in Latin America. After accompanying Ixil witnesses and their supporters involved in the ongoing case for genocide against former general José Efraín Ríos Montt, she returned to the U.S. in May.

Roots of Genocide

“One of the primary complications of studying genocide, and what precedes it, is that the process is not linear or easily reductive,” said Taylor Burrows ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the social and political roots of genocide. Faced with the challenges of complicated and interrelated social, political, and historical factors, Taylor teased out elements that she felt most directly contributed to systemic violence in Bosnia and Rwanda. She considers it good news that no single factor launches a path to genocide, offering many junctures for intervention. “As many scholars have reminded us, genocide is a relatively rare occurrence, despite the overwhelming number of ethnically, politically, and nationally diverse states,” said Taylor. “Even within the realm of ethnic conflict, systemic violence is rarely the outcome.”

“One of the primary complications of studying genocide, and what precedes it, is that the process is not linear or easily reductive,” said Taylor Burrows ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the social and political roots of genocide. Faced with the challenges of complicated and interrelated social, political, and historical factors, Taylor teased out elements that she felt most directly contributed to systemic violence in Bosnia and Rwanda. She considers it good news that no single factor launches a path to genocide, offering many junctures for intervention. “As many scholars have reminded us, genocide is a relatively rare occurrence, despite the overwhelming number of ethnically, politically, and nationally diverse states,” said Taylor. “Even within the realm of ethnic conflict, systemic violence is rarely the outcome.”

Liberated by Education

From the commencement remarks of President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

…There’s something called the White House Scorecard that purports to measure the “value and performance” of colleges. Here’s what it measures: net price; graduation rate; loan default rate; the median amount borrowed; and the type of job and salary earned after graduation.

…There’s something called the White House Scorecard that purports to measure the “value and performance” of colleges. Here’s what it measures: net price; graduation rate; loan default rate; the median amount borrowed; and the type of job and salary earned after graduation.

See the trend? It’s all about money. We need to redefine “ROI - return on investment.” What about the other returns: the return on the individual; the return on the community? Research reveals that the person with a college degree not only earns more, but is more likely to vote, to give to her favorite causes, and to volunteer.

You are graduating with the degree most connected to that exercise of choice—a degree in the “liberal arts.” Why do we use that term? Our classics fellow could tell us the derivation from the Greek and Latin: “liberal” comes from the word for “free.” From medieval times until recent history, universities taught prescribed courses thought to constitute the “knowledge worthy of a free man.”

But our sense of “liberal” is “liberation”—that we might be “liberated by an education…in the service of human freedom.” So says William Cronon in his 1998 article in The American Scholar. What makes a liberally educated person? It’s not a transfusion of facts or content, but rather a set of skills and qualities. To paraphrase Cronon, they are: to listen and to hear; to read and to understand; to write clearly and persuasively; to solve a variety of problems; to respect rigor as a way of seeking truth—to love learning; to practice humility, tolerance, and self-criticism, opening yourself to different perspectives; to understand how things get done in the world; to nurture and empower the people around you, recognizing that “no one acts alone”; to see the connections that allow one to make sense of the world and act creatively within it.

Is this sounding familiar? It should. I think I just described the qualities of your Marlboro education. I’ve lavished some of our last moments together on these to make Cronon’s final point: “Education for human freedom is also education for human community.” In other words, for the “social good,” the culture of connection.

Recently a student told me, “Marlboro presumes tremendous individual capacity and responsibility.” That’s what education for liberation teaches. Why don’t we have a Scorecard for becoming an educated citizen? …Take all those skills you gained researching, organizing, and writing your Plan, and with confidence and joy, believe in yourself and your powers as a liberated and liberating citizen.

The Mismeasure of Marlboro’s Coolness

By Matt Ollis

How sustainable is Marlboro College, relative to other colleges? There are several systems out there that let us try to answer that. One of the most prominent is Sierra magazine’s “Cool Schools” survey, which Marlboro has participated in for several years. Each year the Sierra Club circulates a set of questions with a focus on environmental sustainability, ranging from indoor air quality to environmental studies curriculum. Any college or university that wishes to participate can submit answers; these are then evaluated and the participants are ranked, with the 10 highest-scoring schools getting top billing.

Over the last few years, Marlboro’s ranking on the Sierra list has been as high as 34th and as low as 96th. A tool that tells us that we’re probably somewhere between average and excellent is not especially useful to us, or to prospective students who may use this as a criterion for college selection. Our practices have not changed dramatically during this time, so where does this variability come from? The issue is with Sierra’s changing methodology over time and a general bias against small schools, like Marlboro, where sustainability measures may require a more nuanced approach.

We are not the only college to have been frustrated with the cool-measuring process, and over the last few years the number of participants has been dropping. In 2010 a group of 20 or so colleges withdrew from the Sierra process entirely and put together criteria that they thought any sustainability ratings system should adhere to. These include an “open scoring process,” one where it is known in advance what points will be awarded for which behaviors, and one that “consider[s] the diversity of organizations pursuing sustainability.”

A recently developed methodology that does meet most criteria, including the two mentioned above, is the Sustainability Tracking Assessment and Rating System (STARS) developed by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. It is certainly comprehensive, with 135 questions, covering every aspect of sustainability in colleges and universities, detailed in the 300-page technical manual. Just as important, especially when it comes to small schools like Marlboro, is the recognition that different aspects of sustainability should be approached differently, depending on the context. It strikes a good balance between rigor and flexibility, kind of like Marlboro itself.

When Sierra announced that they were shifting to the STARS methodology for their 2012 survey, we were hopeful that this would benefit Marlboro, both for sharing our work in this area and as a much more useful internal tool for monitoring and encouraging change. It didn’t work out that way. Minor issues were to be expected in the first year, such as their undisclosed reweighting of the questions and an unwieldy interface that made it much more laborious to complete. But the big issue was how they decided to deal with questions that were completely inappropriate for a particular institution, such as those about the college’s research program or fast food franchises. While STARS excludes such questions for colleges like Marlboro, where these issues do not apply, Sierra inexplicably decided to count them with a score of zero in such cases.

As a result of this, the final list for the 2012 Cool Schools is dramatically skewed toward large schools that can pick up at least something in each category. Marlboro, unsurprisingly, came in near the bottom of the list, in the aforementioned 96th place.

There is no indication from Sierra that they intend to alter their approach, and as they do not reveal their scoring system in advance we cannot tell how they will be evaluating the data this year. As such, we have decided not to submit an entry for 2013.

But it’s not all bad news on the sustainability assessment front for Marlboro. As part of her Plan of Concentration work, Joy Auciello ’13 has compiled the answers to the STARS questions, a gargantuan task. She is also building a website that will let us track our sustainability work internally, using metrics that we find meaningful and that reflect Marlboro’s place in the higher education landscape.

At the time of publication, we know that we will score at least equivalent to a Silver rating in STARS, in other words, more excellent than average. This is no mean feat; the STARS standards are tough. Of the schools that have officially joined STARS, fewer than 50 have a Gold rating and none have the best-possible Platinum. For now Marlboro’s results are unofficial, but with so much work into it and such a positive outcome we will revisit joining STARS in the future. At the very least the process has served to highlight several areas to which we should pay more attention over the coming years. Our hope is to make Joy’s site accessible so that the world can see the details of our efforts and see for themselves how sustainable we are.

Matt Ollis is professor of mathematics at Marlboro and chair of the Environmental Advisory Committee. This spring he co-taught a course, with junior Daniel Kalla and admissions counselor Bill Mortimer, called Painting by Numbers: Using Data to Visualize Marlboro College.

On and Off the Hill

Students in Costa Rica, Paul Nelsen in London, Jason Beaubien in Nigeria, sensitive fernes in "the meadow," Northern Borders in the Latchis Theater, salamander eggs in the woods, and seedlings in the greenhouse. You never know what you will find on and off the hill, but it is sure to edify.

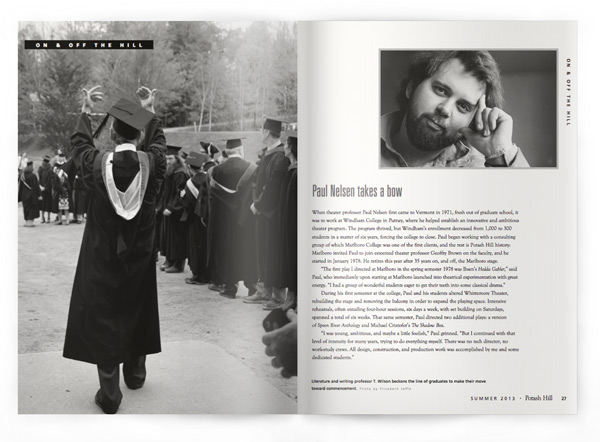

Literature and writing professor T. Wilson (above) beckons the line of graduates to make their move toward commencement. Photo by Elisabeth Joffe

Paul Nelsen takes a bow

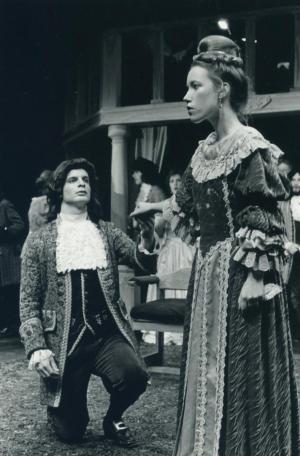

When theater professor Paul Nelsen first came to Vermont in 1971, fresh out of graduate school, it was to work at Windham College in Putney, where he helped establish an innovative and ambitious theater program. The program thrived, but Windham’s enrollment decreased from 1,000 to 300 students in a matter of six years, forcing the college to close. Paul began working with a consulting group of which Marlboro College was one of the first clients, and the rest is Potash Hill history: Marlboro invited Paul to join esteemed theater professor Geoffry Brown on the faculty, and he started in January 1978. He retires this year after 35 years on, and off, the Marlboro stage.

When theater professor Paul Nelsen first came to Vermont in 1971, fresh out of graduate school, it was to work at Windham College in Putney, where he helped establish an innovative and ambitious theater program. The program thrived, but Windham’s enrollment decreased from 1,000 to 300 students in a matter of six years, forcing the college to close. Paul began working with a consulting group of which Marlboro College was one of the first clients, and the rest is Potash Hill history: Marlboro invited Paul to join esteemed theater professor Geoffry Brown on the faculty, and he started in January 1978. He retires this year after 35 years on, and off, the Marlboro stage.

“The first play I directed at Marlboro in the spring semester 1978 was Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler,” said Paul, who immediately upon starting at Marlboro launched into theatrical experimentation with great energy. “I had a group of wonderful students eager to get their teeth into some classical drama.”

During his first semester at the college, Paul and his students altered Whittemore Theater, rebuilding the stage and removing the balcony in order to expand the playing space. Intensive rehearsals, often entailing four-hour sessions, six days a week, with set building on Saturdays, spanned a total of six weeks. That same semester, Paul directed two additional plays: a version of Spoon River Anthology and Michael Cristofer’s The Shadow Box.

“I was young, ambitious, and maybe a little foolish,” Paul grinned. “But I continued with that level of intensity for many years, trying to do everything myself. There was no tech director, no work-study crews. All design, construction, and production work was accomplished by me and some dedicated students.”

“I was young, ambitious, and maybe a little foolish,” Paul grinned. “But I continued with that level of intensity for many years, trying to do everything myself. There was no tech director, no work-study crews. All design, construction, and production work was accomplished by me and some dedicated students.”

In 1979, during the January “Winterim”—a period designed for students to explore new horizons—Paul, along with his wife, kids, and mother-in-law, led a student trip to London, the world’s mecca for theater. The program proved so successful that he repeated it a couple of years later, and subsequently expanded participation to include Marlboro College trustees, other faculty, and friends of the college from the local community. Paul’s trips to London have continued on a regular basis to this day: what began with 11 students and Paul’s family has grown to three trips a year, with over 120 participants from across North America.

“Paul was an excellent leader on our trip to Britain—heavenly days of castles, cathedrals, contemporary theater, and Shakespeare out the wazoo,” commented Gina DeAngelis ’94. “He didn’t just teach acting or directing, he taught us theater folks how to use our talent and develop our skills to reflect, for an audience, life itself.”

In 1983, inspired by his London experiences, Paul invited a former member of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Ted Valentine, to play the lead role in King Lear. The production involved a yearlong immersion process, with a weekly close reading of the play in the fall semester and rehearsals beginning in the Winterim, and featured students as well as members of the community.

“It was an immense project,” recalled Paul. “Three quarters of the auditorium at Persons was the stage. There were only a hundred or so seats at the back of the auditorium. It was an immense space with giant stone arches.”

The following year Paul worked on Sophocles’ Antigone and a Harold Pinter play, The Birthday Party. These high-profile projects required Paul to raise money, some of which came out of his own pocket. Paul was selfreportedly obsessed with achieving something that was exceptional, beyond standard intercollegiate quality. With a lack of technical infrastructure and reliable financial support, however, he became unable to sustain the energy for such an ambitious program.

“At first, when I started, it was possible to get by—perhaps by sheer mania, but I cannot say I regret that,” Paul joked. “The theater program has changed over the years. When I first came here, there was an emphasis on performance as a medium for learning. In the first 15 years I was here, I directed 28 productions. Students collaborated actively in the design and production aspects, but like Geoff Brown before me I was involved hands-on with all elements of putting on the shows—as well as teaching a full load of classes and tutorials.”

“At first, when I started, it was possible to get by—perhaps by sheer mania, but I cannot say I regret that,” Paul joked. “The theater program has changed over the years. When I first came here, there was an emphasis on performance as a medium for learning. In the first 15 years I was here, I directed 28 productions. Students collaborated actively in the design and production aspects, but like Geoff Brown before me I was involved hands-on with all elements of putting on the shows—as well as teaching a full load of classes and tutorials.”

In 1985, Paul sought to expand Marlboro’s capabilities by helping a group of local citizens purchase the former arts building at Windham College, which they renamed the River Valley Playhouse and Art Center. The project aimed to collaborate with Middlebury and Smith colleges to develop a summer theater program with professional actors, students, and faculty from all three institutions and produce a summer season of three or four plays. Concerned about the economic prospects and under financial stress, Marlboro pulled out of the project before its launch. Paul adjusted, using community actors to deliver a season of plays: Chekhov’s The Seagull, Good by C.P. Taylor, and Noël Coward’s Present Laughter. “They were artistically successful, and ticket sales covered all expenses,” Paul remarked with a smile.

Over the next decade, Paul continued to support student productions but decreased the frequency of his own. In 1996, he directed his final play, Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, and began to focus his teaching on dramatic literature as well as on exploring the history and practices of theater and film from diverse angles, often in collaboration with other faculty.

“The impressive works produced by Marlboro students are the greatest testaments to Paul’s ability to nurture and inspire,” declared Edward Isser, professor and chair of theater at Holy Cross College. “Possessing an encyclopedic knowledge of theater and a generosity of spirit, Paul has been a remarkable teacher, a treasured colleague, and a transformative mentor.”

“The impressive works produced by Marlboro students are the greatest testaments to Paul’s ability to nurture and inspire,” declared Edward Isser, professor and chair of theater at Holy Cross College. “Possessing an encyclopedic knowledge of theater and a generosity of spirit, Paul has been a remarkable teacher, a treasured colleague, and a transformative mentor.”

“One of the reasons I chose Marlboro College was so that I would have professors who really cared about, and interacted with, their students,” said Jesse Nesser ’13. “Paul Nelsen turned out to be exactly the kind of teacher I had hoped for. His curiosity, passion, insight, and dedication extend beyond his department and his classroom.”

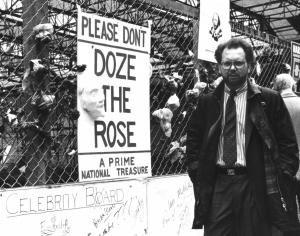

In the mid-1990s, Paul was one of a dozen National Endowment for the Humanities Fellows who convened at the Folger Shakespeare Institute in Washington, D.C., to explore practices of teaching Shakespeare through performance. His research and publications in academic journals on Early Modern English playhouses resulted in an invitation to serve from 1990 to 2002 on the Academic Advisory Board for the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London.

In 2007 Paul collaborated with visual art professor Tim Segar and music professor Stan Charkey to create a field-based, summer “interarts” intensive encompassing eight weeks of seminars and experiential encounters. This included live performances of theater and dance, numerous concerts, and diverse exhibitions of visual art.

“We got as far west as Cooperstown, New York, to the Glimmerglass Opera, the New York City Ballet at Saratoga, the Williamstown Theater for a few shows, some dance festivals around the area, and ended with our wonderful own Marlboro Music Festival right here,” Paul explained. As if that was not enough, the group stayed in London for another three weeks, following the same model.

Not at all coincidentally, one of Paul’s final courses in spring 2013, titled Happy Endings, was an exploration of ways in which different kinds of plays and films arrive at closure.

Not at all coincidentally, one of Paul’s final courses in spring 2013, titled Happy Endings, was an exploration of ways in which different kinds of plays and films arrive at closure.

“Only Paul would choose to end his Marlboro career with a course on Happy Endings,” remarked Dana Howell, professor of cultural history. “The class offers his students—as always—his enormous range of knowledge of theater and film, along with his critical insights and his open-ended curiosity about new ways of telling a story through performance.”

His own closure at Marlboro is made much easier by the many retirement projects that await him at home.

“In many ways an academic life is a wonderful rehearsal period for retirement. I can look at it as if it is a very long sabbatical,” Paul quipped. “I will continue to conduct my London seminars, three of which I will lead in 2013, possibly four in 2014—interest among participants keeps growing. I have boxes full of research for two book projects, and a number of essays that I may return to.”

“Paul has contributed both breadth and depth to the whole college in several ways,” remarked Tim Little, retired history professor. “He sees the theater as a powerful force in the intellectual world, both to the performers and their supporters and to the audiences that observe them.”

Never at a loss for eloquent words, Paul waxed modest regarding his hopes for the future of theater at Marlboro.

“The best thing for me to do is leave it behind to allow others to reinvent theater at Marlboro in their own vision,” he stated. “We can create a program of excellence where theater, dance, film, music, and visual arts begin to see themselves not as isolated fields of study but as ‘liberal’ investigations of shared interests, creatively and continuously pursuing the joy and dignity of learning.” —Christian Lampart ’16

Students take TESOL to Costa Rica

Southern Vermont is remarkable in so many ways, but having large numbers of people learning English as a second language is not one of them. It was imperative for the students in the TESOL (teaching English to speakers of other languages) Certificate teaching practicum, which involves six hours of observed classroom teaching, to find some. Fortunately Mary Scholl, TESOL instructor at the Marlboro College Center for Graduate and Professional Studies, is also director of Centro Espiral Mana, a language school and teacher training organization in Costa Rica.

Southern Vermont is remarkable in so many ways, but having large numbers of people learning English as a second language is not one of them. It was imperative for the students in the TESOL (teaching English to speakers of other languages) Certificate teaching practicum, which involves six hours of observed classroom teaching, to find some. Fortunately Mary Scholl, TESOL instructor at the Marlboro College Center for Graduate and Professional Studies, is also director of Centro Espiral Mana, a language school and teacher training organization in Costa Rica.

“We wanted to provide an authentic teaching experience where Marlboro students had to respond to the language-learning needs of students from a different linguistic and cultural background,” said Beverley Burkett, director of the TESOL graduate program and instructor for the TESOL Certificate. Twelve students went to Centro Espiral Mana with Beverley during spring break for eight intense days of preparation and teaching.

The Marlboro students took a project-based approach to lesson planning and design that involved using English to learn about and protect the local environment. In particular they focused on the nature and environmental issues associated with a trail along the local river that had been developed by town government to promote awareness and conservation.

“We were excited about not only teaching English but also contributing to increased environmental awareness and sustainable job opportunities for local inhabitants,” said Bev. “One local teenager said, ‘We learned English, but most of all we learned how to look after our river.’”

“When we first arrived, our students knew a few phrases, but they mostly knew isolated vocabulary,” said sophomore Louisa Jenness. “We worked a lot on forming sentences. Hearing our students start to express themselves for the first time was a beautiful thing.”

Junior Ben Glatt said, “For me, the highlight of the trip were those moments standing in front of the students when they really got it. That joy of discovery was amazing both to witness and to be a part of.”

“The Marlboro TESOL students worked together in cohesive groups and never missed a beat in a very tight schedule of work. I was really proud of them,” said Bev. “One student said he had learned that ‘It’s not about me.’ That summed up the miracle that I witnessed— the group shifted from focusing on themselves and their needs to being teachers responsible for the learning of others. Remarkable!”

The trip to Costa Rica was just one of three international trips that brought Marlboro students to new horizons over spring break. Students in a course on Cuban history spent nine days immersed in their subject, joining anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson and American studies professor Kate Ratcliff on a field research trip to Havana. Five other students explored mosques, palaces, and markets in Turkey with art history professor Felicity Ratte and ceramics professor Martina Lantin, part of their course on ceramic tiles in Seljuk and Ottoman architecture.

Speakers bring global issues to Marlboro College

“What I’ve come to realize through the reporting that I do is just how interconnected our world has become, for better or for worse,” said National Public Radio correspondent Jason Beaubien in a Marlboro lecture last April. “And the effects of it are often not what you would expect.”

“What I’ve come to realize through the reporting that I do is just how interconnected our world has become, for better or for worse,” said National Public Radio correspondent Jason Beaubien in a Marlboro lecture last April. “And the effects of it are often not what you would expect.”

In a talk titled “On Wars, Plagues, and Disaster,” Beaubien described traveling to northern Nigeria last fall, to a cluster of tiny villages suffering from lead poisoning at unheard-of levels. More than 400 children had died, and many more were disabled by the poisonous heavy metal, as a result of local gold mining efforts using crude extraction techniques. This environmental disaster, ironically in remote villages that don’t even have electricity, was driven by global markets.

“This disaster wouldn’t have happened if the international price of gold hadn’t gone to incredibly high levels over the last decade,” said Beaubien. Although the gold deposits are marginal, and interlayered with deadly lead, they became profitable enough for miners to make 40 or 50 dollars a day. “The cost of remediation is far greater than any of the profits they have managed to reap.”

Beaubien gave several other examples of the reach of global impacts, from earthquakebroken Haiti to the scourge of tuberculosis in Moldova. Not all of these impacts are negative, as in the case of the campaign to eradicate polio. While there were once hundreds of thousands of polio victims around the world, last year there were only 223 new cases, the lowest in history.

“Polio eradication gets at the great possibilities of what humanity could accomplish around the globe,” said Beaubien.

Other speakers at Marlboro this spring included the inimitable Tim Little, retired history professor and storyteller par excellence, who spoke about the political career of Charles de Gaulle, the “Liberator of Paris.” With his usual wit and whimsy, Tim helped clarify the circumstances of de Gaulle’s rise to power and the conditions of French politics that sustained it until 1970.

Cynthia Enloe, a Clark University professor of political science, also appeared in Ragle in April, presenting a talk titled “Is allowing women soldiers to serve in combat a step toward real liberation?” The presentation traced the growth of militaristic values in the U.S., and pointed out that women serving on the front line was nothing new, much less the result of egalitarian motives.

“Insofar as a country is militarized, women’s exclusion from the military becomes women’s exclusion from public, valued life,” said Enloe.

These three lectures filled out a very full spring of events, which also included readings by renowned poets and fiction writers, dance and theater performances, and of course the regular Music for a Sunday Afternoon concerts.

For details on upcoming events, go to www.marlboro.edu/news/events.

Cultivating the heart of campus

Last September, many students, staff, and faculty joined together to clear juniper, scrape rock, prepare the soil, and get their hands into the earth planting hundreds of plants on the hill by the admissions building. The result is a welcoming gateway to the college, leading from the visitor’s parking area to the heart of campus. This summer the community is turning its attention to that heart, with a significant landscaping project in the open space between the dining hall and campus center, a focal point for many campus activities.

Last September, many students, staff, and faculty joined together to clear juniper, scrape rock, prepare the soil, and get their hands into the earth planting hundreds of plants on the hill by the admissions building. The result is a welcoming gateway to the college, leading from the visitor’s parking area to the heart of campus. This summer the community is turning its attention to that heart, with a significant landscaping project in the open space between the dining hall and campus center, a focal point for many campus activities.

“The new south bank enhances our sense of place and the kind of place Marlboro College is, with our attention to environmental issues and hands-on learning and exploration,” said William Edelglass, philosophy professor. The redesign of the meadows, as the area behind the dining hall has been called, “will create a more inviting, beautiful, useful, and cohesive heart of the Marlboro campus,” added William.

The project was accomplished with the initiative and support of students, faculty, and staff over the past year and is the second half of a larger landscaping effort funded by a generous donor and led by the Regenerative Design Group (RDG), a permaculture-inspired landscape design firm based in Greenfield, Massachusetts. In the fall semester, professionals from RDG taught a course on the principles of design to regenerate natural and human communities, focusing on the meadows as a class project.

“Ideas about what we wanted in the meadows were gathered from the community, and initial designs were drawn up,” said William, a member of the Standing Building Committee that oversees campus improvements. “These designs were then presented at Town Meeting and hung on a board in the dining hall to gather feedback and more ideas. The new design responds to the desires of the community.”

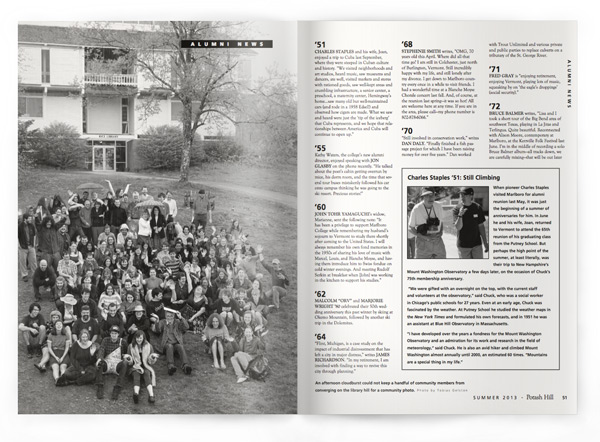

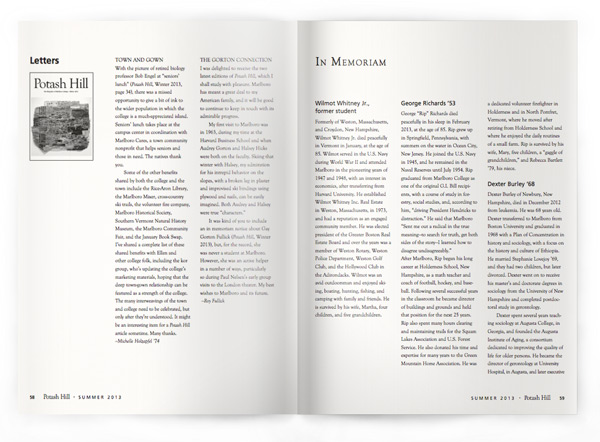

“Ideas about what we wanted in the meadows were gathered from the community, and initial designs were drawn up,” said William, a member of the Standing Building Committee that oversees campus improvements. “These designs were then presented at Town Meeting and hung on a board in the dining hall to gather feedback and more ideas. The new design responds to the desires of the community.”