On and Off the Hill

Kipling scholors ogling over artifacts, students discovering the wonders of mentoring, classes shooting a new Movie from Marlboro, new faculty and retiring faculty and not-so-retiring faculty. On and Off the Hill is where you find all the Marlboro news that's fit to print.

Kipling scholors ogling over artifacts, students discovering the wonders of mentoring, classes shooting a new Movie from Marlboro, new faculty and retiring faculty and not-so-retiring faculty. On and Off the Hill is where you find all the Marlboro news that's fit to print.

Kipling Society comes to Marlboro

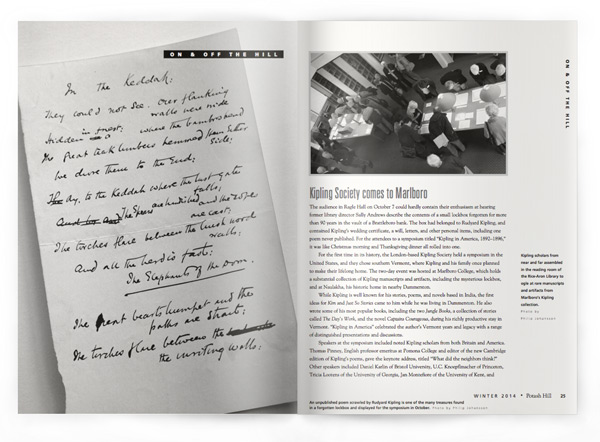

The audience in Ragle Hall on October 7 could hardly contain their enthusiasm at hearing former library director Sally Andrews describe the contents of a small lockbox forgotten for more than 90 years in the vault of a Brattleboro bank. The box had belonged to Rudyard Kipling, and contained Kipling’s wedding certificate, a will, letters, and other personal items, including one poem never published. For the attendees to a symposium titled “Kipling in America, 1892–1896,” it was like Christmas morning and Thanksgiving dinner all rolled into one.

For the first time in its history, the London-based Kipling Society held a symposium in the United States, and they chose southern Vermont, where Kipling and his family once planned to make their lifelong home. The two-day event was hosted at Marlboro College, which holds a substantial collection of Kipling manuscripts and artifacts, including the mysterious lockbox, and at Naulakha, his historic home in nearby Dummerston.

While Kipling is well known for his stories, poems, and novels based in India, the first ideas for Kim and Just So Stories came to him while he was living in Dummerston. He also wrote some of his most popular books, including the two Jungle Books, a collection of stories called The Day’s Work, and the novel Captains Courageous, during his richly productive stay in Vermont. “Kipling in America” celebrated the author’s Vermont years and legacy with a range of distinguished presentations and discussions.

Speakers at the symposium included noted Kipling scholars from both Britain and America. Thomas Pinney, English professor emeritus at Pomona College and editor of the new Cambridge edition of Kipling’s poems, gave the keynote address, titled “What did the neighbors think?” Other speakers included Daniel Karlin of Bristol University, U.C. Knoepflmacher of Princeton, Tricia Lootens of the University of Georgia, Jan Montefiore of the University of Kent, and Judith Plotz of George Washingon University. David Richards, editor of the definitive Kipling bibliography, discussed a recently discovered manuscript with writing advice from Kipling to his sister-in-law Josephine.

The eagerly anticipated Marlboro collection included the humorous biography of publisher George Putnam, “born of poor but most disreputable parents,” carefully printed on a single sheet of toilet paper. It also included a little-known but important memoir by Mary Cabot, a local historian and close friend of the Kiplings, who gives a rare and intimate picture of their personal lives and relations.

“This is particularly valuable because they were reclusive,” said Tom Ragle, former president of Marlboro College, who presented the Marlboro Kipling collection along with Andrews and current library director Emily Alling. “They tried to shun the unwanted publicity that seemed to follow them about. By that time Kipling was a major celebrity.”

The second day of the symposium was hosted at Naulakha, which the Kiplings designed and had built for them—now beautifully and authentically restored by the Landmark Trust USA. In addition to a tour of Naulakha, participants were treated to a talk by Charles Fish of the Dummerston Historical Society on “Vermont and Vermonters in Kipling’s Day,” as well as readings by Mary Hamer from her novel about Kipling and his sister, Kipling and Trix.

New faculty member brings activism to anthropology

By Shannon Haaland ’17

“I strongly feel that the experts are everyday people,” said Rebekah Park, who joined Marlboro as professor of anthropology in August. She was referring to her experience working in Washington think tanks, which tended to rely upon “experts.” “I was very concerned that people in Washington were creating policies without having a good understanding of how everyday people thought and approached the same social problem.”

Rebekah didn’t always want to be an anthropologist. When she was in high school, she wanted to do social policy analysis, and she hasn’t strayed far from that goal. As an anthropologist, she is very interested in exploring social problems and conducting social science research to contribute to solutions. Anthropology has always been a great source of curiosity to Rebekah, and while she enjoyed her high school anthropology course, her interest solidified in the applications of human rights research she encountered at universities.

“Anthropologists attempt to understand social problems from the bottom up,” she said, “meaning they look at everyday people in communities as experts, and they are very committed to that perspective. That’s why I became an anthropologist, because I wanted to have the tools to do social research at that level of social analysis.”

After receiving her undergraduate degree in anthropology at Northwestern, Rebekah got her master’s in applied medical anthropology while a Fulbright scholar at the University of Amsterdam. This led to her co-editing the book Doing and Living Medical Anthropology: Personal Reflections as well as writing related articles on heroin addicts and asylum seekers in Amsterdam. After that she received her doctorate in sociocultural anthropology from UCLA, one of the top programs in the country, taking particular interest in post-conflict areas, transitional justice, and human rights, especially in Latin America.

Rebekah observed fundamentally different paradigms of anthropology studies in Amsterdam versus those at American universities. In American anthropology there tends to be a distinction made between theory and practice, while it is the norm for Dutch anthropologists to seamlessly navigate academia and policy or NGO work without mention of a theory/practice divide. This is where Rebekah’s research interests lie, and it is the approach she plans to use with her students.

“Of course there is room for knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but I want students to know that they are in a privileged position to spend time studying something,” she said. “I want them to understand that perhaps they should think about the end meaning, or product. Especially in the climate we are living in now, I think people have to be articulate as to why a liberal arts education is important, and I think that begins with their own projects.”

Rebekah herself is a case in point, having spent two years in Argentina for her dissertation research, interviewing former political prisoners of the military dictatorship there in the ’70s and

’80s. The Association of Former Political Prisoners of Córdoba, whose members survived abduction, torture, and illegal imprisonment, invited her to work with them to document their memories of the past and to actively participate in their current political organizing activities. Unlike the desaparecidos (the disappeared persons), the former political prisoners, for reasons unknown to them, were made to reappear in legal prisons and survived. Because they were marginalized for having survived, Rebekah was the first scholar to work with an organized group of former political prisoners. She has just completed her first book based on her research in Argentina, called The Reappeared, to be published by Rutgers University Press as part of the Genocide, Political Violence, Human Rights series.

Rebekah herself is a case in point, having spent two years in Argentina for her dissertation research, interviewing former political prisoners of the military dictatorship there in the ’70s and

’80s. The Association of Former Political Prisoners of Córdoba, whose members survived abduction, torture, and illegal imprisonment, invited her to work with them to document their memories of the past and to actively participate in their current political organizing activities. Unlike the desaparecidos (the disappeared persons), the former political prisoners, for reasons unknown to them, were made to reappear in legal prisons and survived. Because they were marginalized for having survived, Rebekah was the first scholar to work with an organized group of former political prisoners. She has just completed her first book based on her research in Argentina, called The Reappeared, to be published by Rutgers University Press as part of the Genocide, Political Violence, Human Rights series.

An enthusiast of international opportunities, Rebekah said that travel is one of the most important anthropological experiences someone can have. “The first international experience that changed me was when I was in Korea—I was 13—because it taught me what it felt like to be part of a majority,” Rebekah said. “There are completely different ways of organizing society, and sometimes you forget that when you stay in one place.”

Rebekah’s favorite thing about teaching at Marlboro is the one-on-one advising. “When you teach at a smaller college, you get to have more-personal interactions with students,” she said, emphasizing the atmosphere of Marlboro’s close-knit community.

“I am thoroughly enjoying my interactions with students so far at Marlboro,” she said. “I’m teaching two classes, Introduction to Sociocultural Anthropology and Social Suffering, and I really enjoy speaking with all of my students. They’re really smart.” She craves gaining the knowledge of what motivates a student intellectually and being able to add structure to a student’s independent creativity.

Working with the Marlboro faculty excites Rebekah; she is enthused to try co-teaching a class, as well as designing new classes. She wants to bring popularly debated topics at Marlboro, such as race and gender, into new light with analytical classes, and to teach more advanced tutorials in violence and human rights. Rebekah is also excited to understand and explore the concept of the Marlboro Plan of Concentration.

“That’s why Marlboro is ideal, because there is so much emphasis on figuring out what you want to do specifically on your Plan and the tutorial. I felt as though it spoke to my interests and strengths in teaching,” she said.

Shannon Haaland is a freshman at Marlboro College interning as a writer in the marketing and communications department.

Students find big rewards as Big Brothers/Sisters

While Marlboro students spend most of their waking hours with other students, there are a few who are reaching out to include younger people in their circle, for mutual benefit. This year, 15 students have served as Big Brothers and Big Sisters (BBBS), committing for the full academic year to act as mentors to “Littles” at Marlboro Elementary School. Nine of those mentors returned from last year, so are completing their second year of service.

“The Big Brothers Big Sisters program at Marlboro College is a strong example of a community-based, service-learning experience,” said Stefanie Argus, student life coordinator, who spearheaded the program. “Students share the double gifts of time and commitment—sticking to a regular weekly appointment shows dedication.”

Mentors carpool to the elementary school four out of five weekdays to interact with Littles ranging from kindergarteners to seventh graders. They have lunch together, then head outside to build forts in the woods and play soccer, basketball, or foursquare. For quieter activities, Bigs and Littles read together, make friendship bracelets, or do seasonal crafts like gingerbread houses.

In addition to programs sponsored by BBBS of Windham County, such as a fall harvest party, a bowl-a-thon, and a kickball tournament, there are other opportunities for partnership right on the Marlboro campus. These have included a visit to the college farm and greenhouse, in collaboration with the Farm Committee and the farm cottage, and a Mud Run in October to benefit BBBS. On a chilly Saturday morning, 19 hearty participants showed up to run the 1.2-mile trail, with obstacles including a tower climb, inflatable raft traverse, rope spiderwebs, balance beams, and rope shimmy over the fire pond. The event raised $198, all of which was donated to BBBS.

“I’ve been lucky to be involved with this opportunity for community collaboration with Marlboro Elementary School, and have personally been seeking other ways to invite additional partnerships between our two schools,” said Stefanie. “Ideally, I would love for college students to continue their matches throughout their time at Marlboro, and I hope that the program does have longevity and sustained interest.”

“I’m extremely impressed by the dedication of our students who participate in the BBBS collaboration,” said Desha Peacock, director of career development. “Beyond building good karma and a résumé, volunteering offers an opportunity to improve the quality of life for others and instills a civic duty in students that hopefully will remain an influence in later life. For students interested in early childhood education, it also provides a unique opportunity to experience an elementary school environment from a different perspective, providing insight into possible career paths.”

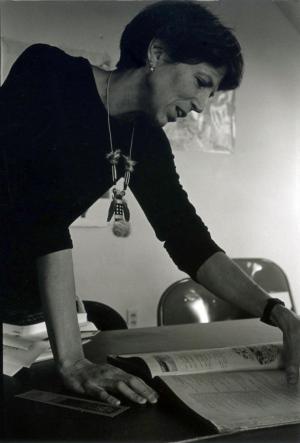

Carol Hendrickson retires; Marlboro thinks the world of her

“People are born into worlds already rich with meaning, and grow up learning multiple senses of place,” anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson wrote in Potash Hill (Winter 2010). “When I first started doing anthropology fieldwork in Guatemala, I had a great deal of catch-up work to do to begin to navigate what others already knew about the places all around me.” Carol wasted no time gaining a sense of place at Marlboro when she first joined campus in 1989. She retires this year after 25 years of teaching “the three Rs:” reading, writing, and research in the form of fieldwork, considered the hallmark of anthropology.

“People are born into worlds already rich with meaning, and grow up learning multiple senses of place,” anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson wrote in Potash Hill (Winter 2010). “When I first started doing anthropology fieldwork in Guatemala, I had a great deal of catch-up work to do to begin to navigate what others already knew about the places all around me.” Carol wasted no time gaining a sense of place at Marlboro when she first joined campus in 1989. She retires this year after 25 years of teaching “the three Rs:” reading, writing, and research in the form of fieldwork, considered the hallmark of anthropology.

Carol came to Marlboro after a year of teaching at Carleton College, with a doctorate from the University of Chicago. She had written her dissertation on women weavers in Guatemala, which resulted in her book Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemala Town (1995), selected by Choice as one of the best new books in anthropology. Like many faculty members, she was drawn to the small size at Marlboro and the ability to work closely with students.

“I guess I couldn’t really predict this from the start, but it quickly became clear that I loved doing tutorials,” said Carol. “Moreover, my family is from New England; my undergraduate experience was in New England (Bates); it was like coming home. It was just a really great place.”

According to Carol, the study of anthropology is important “because it teaches us that, culturally speaking, we’re not the only game in town.” In the classroom she liked to teach her students how to question assumptions about their own world and also come to understand the logic of worlds that initially might seem very strange. Carol believes that this permits her students to see other people’s lives, not to mention their own, with fresh eyes.

“Carol has always been welcoming of diverse ideas, and engaging with other faculty and disciplines in an appropriately critical way,” said Jeff Bristol ’09, who is now in a doctoral program in anthropology at Boston University. “This kind of interaction really is the hallmark and the benefit of being an anthropologist, and Carol was exemplary of that. I really couldn’t have had a better or more dedicated first mentor who was both theoretically strong and empirically conscious.”

“Carol brought to her teaching a cultural anthropologist’s keen way of observing the universe, finding unexpected connections, and unearthing the everyday lyrical-ness of life,” said Sari Brown ’11, who did her Plan of Concentration in religion and anthropology. “Without even meaning to, she was constantly collaborating with her students in their research, as she had an incredible knack for discovering, by chance, articles and ideas and occurrences that connected to their work.”

“I think there is flexibility here for me to really teach anything,” said Carol, who often collaborated with other faculty members in classes. “Anthropology is a subject that people don’t know a lot about, and so particular classes might bring in visual arts students, for example,

and then they perhaps end up writing a Plan paper on the subject. Having control over your curriculum is really a plus.”

In addition to teaching popular classes like Ethnobiology, Senses of Place, Anthropology of Art, and Thinking Through the Body, Carol served as dean of faculty during the 1990s and director of world studies in the 2000s. She was a clear choice for the latter, with her international background and fieldwork experience.

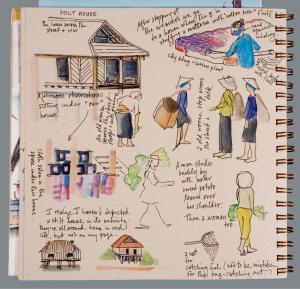

“One of the things I really appreciated and made use of at Marlboro, in many ways, was the funding to go abroad,” Carol said. Her first Marlboro course trip was to the Yucatan in 2001, with biologist Bob Engel and ceramist Michael Boylen and five students, two of whom were in the World Studies Program (Potash Hill, Summer 2001). “That led to other trips such as the one in Vietnam, and co-leading trips to Cuba with Kate Ratcliff.” As director of world studies she also visited students doing WSP internships and study-abroad programs in Mexico and Spain. “Those were really excellent opportunities because I got the chance to see how those programs worked on the ground.”

Along the way, Carol developed a method of “visual field notes” that has augmented her learning process in the field and has been a key element of her recent academic work. Recent articles on the subject include “Visual field notes: Drawing insights in the Yucatan,” in Visual Anthropology Review (2008), and “Ethno-graphics: Keeping visual field notes in Vietnam,” in Expedition magazine (2010).

“Marlboro has been great in supporting research trips to Guatemala in the past 20 years,” said Carol. “I’m happy that I’ve kept a modest writing career in addition to the time teaching.” In 1999 Carol was awarded a coveted Fulbright-Hays faculty research grant for her work in Guatemala. In 2002 she came out with Tecpán Guatemala: A Modern Maya Town in Global and Local Context, co-written with Edward Fischer, currently being translated for publication in Spanish.

“Marlboro has been great in supporting research trips to Guatemala in the past 20 years,” said Carol. “I’m happy that I’ve kept a modest writing career in addition to the time teaching.” In 1999 Carol was awarded a coveted Fulbright-Hays faculty research grant for her work in Guatemala. In 2002 she came out with Tecpán Guatemala: A Modern Maya Town in Global and Local Context, co-written with Edward Fischer, currently being translated for publication in Spanish.

“Carol managed to stay well abreast of the anthropological world at large from Potash Hill, which itself can be challenging,” said Jeff. “More than this, however, she continued to do fieldwork, which is not only extremely commendable, but also rare among sociocultural anthropologists, many of whom are content to write a dissertation and then surround themselves with the world of theory.”

In fact, Carol is looking forward to doing more fieldwork in her retirement, visiting field sites at new times of year, reviewing her decades of notes and experimenting with new writing styles. She said that the challenge will be to keep up the energy and get projects done, but nobody else seems to doubt her ability to do that. As recently as November, she traveled to Chicago for the American Anthropological Association meeting to give two talks. One of them, called “Che’s Socks,” was about clothing and other relics of the Cuban Revolution, based on her many class trips to Cuba, and the other was about her visual field notes.

“One part of Marlboro that I have appreciated is my colleagues, and some students have become colleagues as well,” she said. “While they aren’t always in my disciplinary area, our conversations have been very important and pushed my work in new directions.” For example, for an article she’s writing on experiential learning in Vietnam, she asked Tessa Walker ’07 to send her some of her journal pages from their trip there together. “It’s great to keep up the conversations, and to hear what work they are doing, what graduate programs they are in.” Tessa is currently doing research on skateboarding as a mode of transportation for her master’s thesis project in urban studies at Portland State University, Oregon.

Sari said, “Carol worked endlessly to accompany her students in their passions, but she never seemed burdened by it; she seemed to really derive satisfaction from it.” Supported by an Aron Grant, Carol traveled to Bolivia with Sari, and collaborated with her on experimental, sensory-based ethnographic fieldwork. “Throughout the whole process, her humble but incredibly cultivated way of observing people and environments became a model not only of doing anthropology but of living in community that I will carry with me for the rest of my life.”

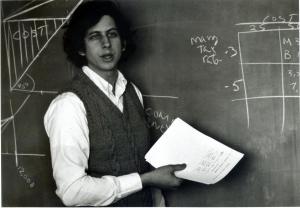

Jim Tober explores economics of retirement

“It was a simpler time in many respects, but I knew I wanted to come to a place like Marlboro even though I had never heard of Marlboro,” said economics professor Jim Tober, who joined the faculty in 1973. He described coming “somewhat accidentally,” sending an introductory letter before the college had even advertised the position. But it is no accident that Jim has stayed with Marlboro for 40 years, and made lasting contributions as a social sciences teacher, administrator, and mainstay of both environmental studies and the World Studies Program.

“It was a simpler time in many respects, but I knew I wanted to come to a place like Marlboro even though I had never heard of Marlboro,” said economics professor Jim Tober, who joined the faculty in 1973. He described coming “somewhat accidentally,” sending an introductory letter before the college had even advertised the position. But it is no accident that Jim has stayed with Marlboro for 40 years, and made lasting contributions as a social sciences teacher, administrator, and mainstay of both environmental studies and the World Studies Program.

“Jim arrived my senior year at Marlboro,” said Peter Zamore ’74, an attorney and Marlboro trustee. “He was young, full of energy, and integrated well into the student body. He immediately experienced the essence of Marlboro—providing a solid education through creative use of limited resources.”

Jim came to Marlboro directly from his graduate program in economics at Yale University, where he did his dissertation on the political economy of wildlife conservation in 19th-century America, the subject of his first book. He was looking for a college that would welcome an interdisciplinary approach to economics, and found it in abundance here.

“I was something of an anomaly among economics graduate students in that I spent as much time as I could justify outside of the department, taking classes in anthropology, African studies, and at the forestry school,” he said. “The forestry school, in particular, embodied the kind of scholarly community that I found to my liking, where people of very different trainings shared a common concern, in this instance for natural resources and the environment.” He found the same kind of community in the Marlboro faculty’s shared commitment to interdisciplinary inquiry in the liberal arts.

Jim’s arrival at Marlboro was well timed in

terms of the faculty’s desire to build both the

social science area and environmental studies.

He and colleagues devised and co-taught an

introductory environmental studies course for a

dozen years or so, beginning in the mid-1970s.

He has continued throughout his Marlboro

career to offer many environmental studies

courses, including those on environmental eco

nomics and policy, U.S. environmental history,

land and land-use planning, endangered species

(with biology professor Jenny Ramstetter), and

wildlife law and policy. Jim was the first chair

of the Environmental Advisory Committee,

which advises the president on sustainability

issues, and initiated the adoption of Marlboro’s

Environmental Mission Statement. He organized

a recent faculty retreat on environmental

studies, and has been instrumental in a resurgence of that program.

Jim’s arrival at Marlboro was well timed in

terms of the faculty’s desire to build both the

social science area and environmental studies.

He and colleagues devised and co-taught an

introductory environmental studies course for a

dozen years or so, beginning in the mid-1970s.

He has continued throughout his Marlboro

career to offer many environmental studies

courses, including those on environmental eco

nomics and policy, U.S. environmental history,

land and land-use planning, endangered species

(with biology professor Jenny Ramstetter), and

wildlife law and policy. Jim was the first chair

of the Environmental Advisory Committee,

which advises the president on sustainability

issues, and initiated the adoption of Marlboro’s

Environmental Mission Statement. He organized

a recent faculty retreat on environmental

studies, and has been instrumental in a resurgence of that program.

Meanwhile, Jim’s passion for conservation has been an asset to the local community as well. He was a longtime member (and former chair) of the Marlboro Planning Commission, which guides development decisions in the town. He was also a board member of the Hogback Mountain Conservation Association during the acquisition of this town park property, and is now a member of the town commission governing its management. These activities supported Jim’s teaching on land use and environmental policy, providing practical, place-based case studies for students.

Eminently level-headed and comfortable in the role of administrator, Jim has held several administrative posts at Marlboro, starting with his very first year. He and his wife, Felicia, needed a place to stay, so they were offered an apartment in Random North if he served as dean of students, which he did for two years along with his teaching position. He also did a couple of terms as dean of faculty for a total of seven years, including two years during the crucial transition between presidents Paul LeBlanc and Ellen McCulloch-Lovell. Jim also served as the director of world studies in the early years of that signature program, and again in 1998–2000. “The World Studies Program was the impetus for several research trips, notably to look at wildlife management in Namibia and study the nonprofit sector in Bangladesh, that enlarged my global perspective and informed my teaching.”

But Jim still considers himself primarily a North Americanist when it comes to economics. His second book, Wildlife and the Public Interest: Nonprofit Organizations and Federal Wildlife Policy (1989), was based on his research on wildlife policy in the U.S. during a sabbatical year residency at the Yale Program on Nonprofit Organizations. This affiliation led to his teaching emphasis on the nonprofit sector, which has encouraged several undergraduate students to pursue Marlboro’s graduate and professional program on managing mission-driven organizations.

Over the years, Jim organized his teaching around two broad fields of inquiry, the analysis and comparison of economic systems and the history and development of public policy and collective decision-making, especially as related to the natural environment. He has always struggled with the orthodoxy within the discipline, and with the need to balance mainstream discourse with the range of topics and perspectives Marlboro students bring to the table.

“The standard American economics curriculum—as distinct from my Marlboro offerings—obscures significant disagreement and disarray within the discipline as to the value of this orthodox approach, broadly known as the neoclassical synthesis,” said Jim. “It has been a real challenge for me both to certify that Plan students of economics know what they ‘should’

know and to support them in exploring alternative—and often more useful and interesting—paradigms.” While few students arrive at Marlboro knowing that they want to study economics, many discover what the discipline offers once they are here, and this has provided Jim with generations of truly engaged students.

“The standard American economics curriculum—as distinct from my Marlboro offerings—obscures significant disagreement and disarray within the discipline as to the value of this orthodox approach, broadly known as the neoclassical synthesis,” said Jim. “It has been a real challenge for me both to certify that Plan students of economics know what they ‘should’

know and to support them in exploring alternative—and often more useful and interesting—paradigms.” While few students arrive at Marlboro knowing that they want to study economics, many discover what the discipline offers once they are here, and this has provided Jim with generations of truly engaged students.

“Economics is known as the ‘dismal science,’ and I must admit I was hesitant to dive into the subject when I started thinking about Plan,” said Kelsa Summer ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the economics and politics of development and social change in Africa. “Jim helped me to see how economics can be intriguing, inspiring, and not so dismal after all. He gave me one of the important lenses through which I view the world, and I am very grateful for that.”

“Tutorial with Jim was precisely what Marlboro billed itself as when I first visited,” said Casey Freidman ’12, who did his Plan in the economics and politics of international relations, specifically U.N. food agencies. “Jim was an adept guide through intellectual worlds foreign to me, directing me to new, relevant ideas across a stunningly wide range of thought. He prompted me to clarify my own ideas, but the overarching direction of our examination was always my responsibility.”

Casey described feeling like part of a strange brotherhood of students who worked closely with Jim, “united by this enigmatic wise man.” He said, “It never took long for him to come up in conversation among us. There was often exegesis of his moods and reactions but the typical conclusion was ‘It’s Jim—there’s no knowing.’”

Jim is characteristically enigmatic about his retirement plans, although they will certainly include lots of gardening, traveling, writing, and, a recent fascination, ceramics. How he will focus his continued academic interests, or his quirky hobby of collecting panther TV lamps, there’s no knowing. But his legacy of inspired teaching will be remembered at Marlboro for some time.

“Great teachers don’t only teach you a subject matter; they teach you how to learn,” said Kelsa. “Jim is an expert at that. Some of my favorite hours at Marlboro were spent debating the fine points of economic development with Jim. He taught me how to peel away the layers of an issue, and showed me how in each hard question lies yet another one.”

College receives United Way award

In October, Marlboro College was delighted to attend a community celebration, called Celebrate HOPE, sponsored by United Way of Windham County. While the focus was on stories of generosity and opportunity from across the county, the college had the special honor of receiving the first annual Partner in HOPE Award.

“I am very proud that Marlboro College received this recognition for our community involvement,” said Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president. “This is really a shared honor—many in the college community have participated in vital ways in United Way’s service to the county.”

For example, eight students joined Jodi Clark, director of housing, for a very successful trip to participate in the United Way Day of Caring in September. The team went to Harlow’s Farm in Westminster, Vermont, to glean excess corn and tomatoes from the fields for donation to the Vermont Food Bank. In total, they picked 1,305 pounds of food for Vermont families, and fostered an interest in doing more of this kind of community service.

Movies from Marlboro launches new season

Following on the success of the first Movies from Marlboro film intensive in spring 2012, film professor Jay Craven is again assembling a team of 30 college students and 20 professionals this spring semester to produce a feature film. This year the hands-on film practicum will shoot a film based on Pierre et Jean, Guy de Maupassant’s 1887 novel of family, class, legacy, and self-discovery.

The last Movies From Marlboro production, Northern Borders, premiered to a sell-out crowd at Brattleboro’s Latchis Theatre last April, launching a 100-town tour of New England. The film, based on Howard Frank Mosher’s novel by the same name, stars Academy Award–nominated actors Bruce Dern and Geneviève Bujold.

“We plan to keep it on the road through 2014, with additional play through Netflix, cable, and streaming,” said Jay. “Northern Borders grew out of my long experience working with young filmmakers and my years of producing and releasing ‘north country’ pictures produced on significantly larger budgets. Building on these experiences, and by using recent developments in independent film production and distribution, I believe that Movies from Marlboro will help chart a new course for how independent films get made and distributed.”

Maupassant’s shortest novel, called a “masterly little novel” by Henry James, Pierre et Jean is widely credited with changing the genre of narrative fiction. The book introduces intense psychological complexity into its story of a family brought to the breaking point by startling revelations of legacy and legitimacy. While the novel was set in Normandy, the film adaptation will be set in 19th-century Nantucket, after the demise of the whaling industry and before the rise of tourism on the island.

The Movies from Marlboro program starts with an expedition to the Sundance Film Festival, followed by seven weeks of study, training, and pre-production work on the Marlboro campus. These include core courses in screenwriting and directing, film studies, and French literature. Participants will then move on to Nantucket Island for seven weeks of pre-production and production that will fully immerse students in the culture and practice of an ambitious film shoot.

“We continue to be inspired by John Dewey’s call for ‘intensive learning that enlarges meaning through the shared experience of joint action,’” said Jay. “Organized as the equivalent to a semester abroad, Movies from Marlboro combines the best of liberal arts education, professional preparation, and cultural immersion.”

Apple daze

Some reflections from freshman Shannon Haaland on the annual tradition known as Apple Days, which mysteriously lasts only one day.

It's a Wednesday morning in the Marlboro dining hall, and everything would appear normal, except for the row of apple cider cartons placed by the register and a tray of apples with sticks in them, ready to be dipped in caramel. Travis Wilmot, a senior, sits back in a wooden dining hall chair and grumbles to me about his lack of knowledge on the names of apples, something he feels is crucial for an inhabitant of Vermont to know.

Outside, the yellow beech trees and the reds of maples stand out against the pale, cloudy sky. Students stand around an apple press, taking turns pulling a crank in order to make more apple cider. It takes roughly 36 apples to make just one gallon of apple cider, we find.

Apple trees are a part of Marlboro. The trees are left over from when Marlboro was a collective of two farms. Today they still produce thick harvests of apple on campus each autumn. Slipping on fallen fruit while running late to class is bound to happen at least once, and serves almost as a rite of passage. Students can be seen encircling trees, pointing out which apple looks the most delicious, and then proceeding on a hunt to capture it.

Eating apples is not only an enjoyable tradition, but one that can aid students on their paths of academia. Apples contain boron, which is responsible for the plants' germination, and can also stimulate the brain and help increase mental alertness. Apple Days is a day to celebrate the campus residents, student and fruit alike, and the reminiscences of fall.

Worthy of note

"I had the high honor of serving my country and working as an intern in the American embassy in Berlin, where I had access to the world of diplomats,” said junior Max Barksdale (right). Max worked in public affairs, giving tours to German school groups, writing “extremely unique” memos, and organizing events, including the visit of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle. His internship relates directly to his course of study at Marlboro in international relations. “This year I’m taking a class on American foreign policy, which I now have the honor of saying

I have seen firsthand.” See a video he worked on.

"I had the high honor of serving my country and working as an intern in the American embassy in Berlin, where I had access to the world of diplomats,” said junior Max Barksdale (right). Max worked in public affairs, giving tours to German school groups, writing “extremely unique” memos, and organizing events, including the visit of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle. His internship relates directly to his course of study at Marlboro in international relations. “This year I’m taking a class on American foreign policy, which I now have the honor of saying

I have seen firsthand.” See a video he worked on.

“I demonstrated that the representation of the African woman as disempowered and victim does not reflect the historical reality of the role of the woman,” said Boukary “Abou” Sawadogo in an interview for the African Women in Cinema Blog. Marlboro’s inimitable French professor spoke to blogger Beti Ellerson about his research on marginal figures in his recent book, Les Cinémas Francophones Ouest-Africains (Potash Hill, Summer 2013). There was also an article about his recent film, Salut Y’all: African Teachers on the Bayou, in the June issue of Francophonie, a publication of the RFI global French language radio station.

“I am in Spain, specifically Granada, studying the influences of Islam in Europe, so

the Alhambra was fascinating

to me,” wrote junior Amelia Brown (right) in her blog last semester. She traveled to Spain and Morocco through Central College Abroad, with a side trip to Germany to visit relatives. Despite some transportation snafus and other challenges, Amelia has gained valuable experience and perspectives for her course of study at Marlboro. “How often will I have a chance to live in Europe, to travel through Spain? It’s an adventure, and I am glad I came on it, no matter the challenges it has presented.”

“I am in Spain, specifically Granada, studying the influences of Islam in Europe, so

the Alhambra was fascinating

to me,” wrote junior Amelia Brown (right) in her blog last semester. She traveled to Spain and Morocco through Central College Abroad, with a side trip to Germany to visit relatives. Despite some transportation snafus and other challenges, Amelia has gained valuable experience and perspectives for her course of study at Marlboro. “How often will I have a chance to live in Europe, to travel through Spain? It’s an adventure, and I am glad I came on it, no matter the challenges it has presented.”

Philosophy professor William Edelglass gave a series of invited talks this fall, including two in Oregon in October. He spoke at Oregon State and at Maitripa College, in Portland, about contemporary themes at the intersections of Buddhism and ecology. He also moderated two sessions at the international Association for Environmental Philosophy, in Eugene, for which he serves on the executive committee. In September he appeared at Salisbury University, where he presented two talks, one on Buddhist sand mandalas and one titled “Global Climate Change, Social Justice, and Buddhist Ethics.” He also gave a talk at Susquehanna University, in central Pennsylvania, together with one of their professors, on categories of religion and philosophy in non-western thought.

“I am really enjoying every moment here,” said Abdelhadi Izem (right), the Fulbright Arabic Fellow on campus for the 2013–14 academic year. “I am surprised at how fast students learn Arabic; they’re really very motivated.” Abdel, who is from Morocco, received his B.A. in English studies from ibn Zohr University, and has taught English for the past six years at the Hassan ii High School, in Guelmim. He was

a great addition to the soc

cer team, and organized a Moroccan cultural festival in November, including tea, food, and a fashion show. “I am very fortunate that I was placed in Marlboro,” said Abdel. “It is heaven on earth. I love everyone here.”

“Very few of the new jobs created by construction in Boston’s Chinatown have gone to Chinatown residents, and the library that was torn down in the 1950s has never been rebuilt,” said senior Kara Hamilton. She did a summer internship with the Chinese Progressive Association, a grass-roots community organization in Boston’s Chinatown that is fighting the history of deconstruction and displacement of residents there. She developed materials for a community stabilization march called Tour R Chinatown, and collaborated with high school youth on a small “free library” bookshelf, part of their campaign to bring a library back to Chinatown. “I really valued getting to know the community, and was inspired by their activism—particularly the youth,” said Kara, who is doing her Plan of Concentration in Asian American studies and documentary studies.

“Koha is just one open source library catalog software that

we use, all of which have saved the college gobs of money,” said Elliot Anders (right),

web developer. Marlboro is also among the first colleges to use software called CUFtS and Godot, and last October Elliot and Amber Hunt (Potash Hill, Summer 2013) were invited to

a Koha conference in Reno, Nevada, to share their experiences. They were also able to connect with people they had been collaborating with for

the past three years. “Our talk was an attempt to excite users of Koha to try out CUFtS and Godot, to hopefully grow the user base and interest some developers in contributing to

its development. The greater the number of libraries using it, the more bugs will be reported and special features requested.”

“Koha is just one open source library catalog software that

we use, all of which have saved the college gobs of money,” said Elliot Anders (right),

web developer. Marlboro is also among the first colleges to use software called CUFtS and Godot, and last October Elliot and Amber Hunt (Potash Hill, Summer 2013) were invited to

a Koha conference in Reno, Nevada, to share their experiences. They were also able to connect with people they had been collaborating with for

the past three years. “Our talk was an attempt to excite users of Koha to try out CUFtS and Godot, to hopefully grow the user base and interest some developers in contributing to

its development. The greater the number of libraries using it, the more bugs will be reported and special features requested.”

This fall, ceramics professor Martina Lantin curated a show titled “Disaster, relief, and resilience,” featuring the work of more than 50 artists from across the United States and hosted by the Crimson Laurel Gallery in north Carolina. “The unique aspect of this show is that the artists and the gallery are donating some of the proceeds to benefit the Craft emergency relief Fund (CerF),” said Martina. Based here in Vermont (and employing alumna Carrie Cleveland ’02), CerF provides financial support for artists and craftspeople whose livelihoods have been affected by natural disaster or personal tragedy.

In October, Beverly Burkett (right) was a featured speaker at the international KOteSOL (Korean teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) conference in Seoul, South Korea. The degree chair for Marlboro’s master’s program in teSOL, Bev gave a presentation titled “Developing a personal theory of teaching practice: the role of reflection.” “The conference theme, Exploring the Road Less Traveled:

From Practice to Theory, really resonated with me because

it aligned with our approach here at Marlboro,” said Bev. “We begin with experience and a focus on our practice and theorize from that. Of course, the title brought to mind Robert Frost’s poem

‘The Road Not Taken,’ and, given his connection to the founding of Marlboro, that was an added attraction.”

In October, Beverly Burkett (right) was a featured speaker at the international KOteSOL (Korean teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) conference in Seoul, South Korea. The degree chair for Marlboro’s master’s program in teSOL, Bev gave a presentation titled “Developing a personal theory of teaching practice: the role of reflection.” “The conference theme, Exploring the Road Less Traveled:

From Practice to Theory, really resonated with me because

it aligned with our approach here at Marlboro,” said Bev. “We begin with experience and a focus on our practice and theorize from that. Of course, the title brought to mind Robert Frost’s poem

‘The Road Not Taken,’ and, given his connection to the founding of Marlboro, that was an added attraction.”

In June, Spanish language and literature professor Rosario de Swanson presented a paper in Portugal, at the Universidad Fernando Pessoa. Her paper was part of a symposium on Mexican literature organized by CeiSAL, the European Council for Social research on Latin America. Titled “National Dystopias,” Rosario’s talk centered on the dramatic poems of Mexican feminist Rosario Castellanos.

“Marlboro’s a very interesting place,” said Sean Harrigan (right), Marlboro’s Classics Fellow for the academic year. “My classes are fun, and I enjoy the way tutorials bring me into contact with things I wouldn’t necessarily be reading or thinking about if left to my own devices.” Sean completed his doctorate degree in classics from Yale in May, and has taught both Greek and Latin. His research focus is on the poetry of Archaic Greece, specifically how it was performed. “The fact that our texts survive as ink on paper obscures the amazing reality that what we tend to call poetry is almost always better thought of as song. I’m especially interested

in songs that were performed

as part of religious ceremonies, where the words may tell us something about the rituals in which people were taking part.”

“Marlboro’s a very interesting place,” said Sean Harrigan (right), Marlboro’s Classics Fellow for the academic year. “My classes are fun, and I enjoy the way tutorials bring me into contact with things I wouldn’t necessarily be reading or thinking about if left to my own devices.” Sean completed his doctorate degree in classics from Yale in May, and has taught both Greek and Latin. His research focus is on the poetry of Archaic Greece, specifically how it was performed. “The fact that our texts survive as ink on paper obscures the amazing reality that what we tend to call poetry is almost always better thought of as song. I’m especially interested

in songs that were performed

as part of religious ceremonies, where the words may tell us something about the rituals in which people were taking part.”

Or for the most up-to-date scoop, see:

Potash Phil cosmo.marlboro.edu/potashphil

Facebook www.facebook.com/marlborocollege

Youtube www.youtube.com/user/marlborocollege

twitter www.twitter.com/marlborocollege