Spring 2015

Editor’s Note

In Life of Pi, Yann Martel writes, “I suppose in the end the whole of life becomes an act of letting go. But what always hurts the most is not taking a moment to say goodbye.” We take the time to say several goodbyes in this issue of Potash Hill, principal among them a fond farewell to our fearless leader President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, who will be moving on to hopefully more relaxing things in July.

In Life of Pi, Yann Martel writes, “I suppose in the end the whole of life becomes an act of letting go. But what always hurts the most is not taking a moment to say goodbye.” We take the time to say several goodbyes in this issue of Potash Hill, principal among them a fond farewell to our fearless leader President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, who will be moving on to hopefully more relaxing things in July.

Ellen has always impressed me with her ability to hold a space, whether that’s in the midst of a noisy Town Meeting or a full-house commencement, with warmth and grace. We could hardly do better than remembering Ellen with a heartfelt, personal tribute from our own Peter Mallary, alumnus, parent, and loyal longtime trustee.

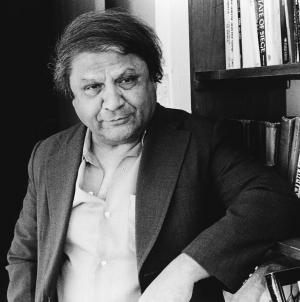

We also take the time to say goodbye to two beloved faculty members, Jaysinh Birjepatil and Willene Clark, who died in January. Each of them left their unique mark on Marlboro during their tenures, as well as after retirement, and the community will miss their presence.

If you don’t already know, I am happy to inform you that Marlboro has appointed Ellen’s successor, Kevin Quigley, who will start serving as president on July 1. Kevin was chosen by a multi-constituent search committee, after an exhaustive process that started with over 200 applicants and ended with his visit to campus in February for all to meet. We look forward to sharing more about Kevin in the next issue of Potash Hill, but in the meantime you can learn a bit on our website under News & Events.

As the snow slowly subsides and is replaced by snowy mud, and then by just mud, and eventually the fullness of spring, we at Marlboro are well aware that nothing stays the same. We are grateful for the positive role so many people have played in making the college what it is, and are heartened by the thought of the many more to come.

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the undergraduate campus was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Ella McIntosh

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: Boot prints along the fire-pond path chart the progress of time and motion at Marlboro College. All community members leave their mark on campus, and none more indelibly than President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, who steps down this summer.

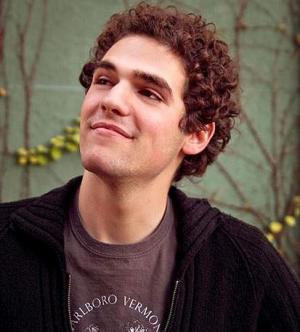

What does a liberal arts education mean to you? To Marlboro junior Edward Suprenant, pictured right, writing is a craft like any other, and free-thinking is a skill to be honed at college. Find out more in a video profile.

What does a liberal arts education mean to you? To Marlboro junior Edward Suprenant, pictured right, writing is a craft like any other, and free-thinking is a skill to be honed at college. Find out more in a video profile.

Marlboro College Mission Statement

The goal of the undergraduate program at Marlboro College is to teach students to think clearly and to learn independently through engagement in a structured program of liberal studies. Students are expected to develop a command of concise and correct English and to strive for academic excellence informed by intellectual and artistic creativity; they are encouraged to acquire a passion for learning, discerning judgment, and a global perspective. The college promotes independence by requiring students to participate in the planning of their own programs of study and to act responsibly within a self-governing community.

The mission of Marlboro College Graduate and Professional Studies program is to offer responsive, innovative education of the highest standard in professional studies in the topic areas of management, technology, and teaching. The educational practice of the graduate program fosters the development of critical thinking, articulate presentation, coherent concepts and arguments, superior writing skills, and the ability to apply creative, sustainable solutions to real world problems.

Up Front

As animals with limited senses and cognition, our perception of the world around us is merely a fraction of the information available in a moment. With science, and the right instruments, we can obtain quantitative data to help us understand exactly how much information our limited anatomy is missing, but this may not appeal to our subjective understanding of reality and primal aesthetic. So, I challenge myself to portray these elusive worlds in a manner palpable and stimulating to our insufficient eyes. In my work I attempt to show the details our eyes are not sensitive enough to perceive in the dark and the events that we are perhaps not patient enough to watch unfold.

As animals with limited senses and cognition, our perception of the world around us is merely a fraction of the information available in a moment. With science, and the right instruments, we can obtain quantitative data to help us understand exactly how much information our limited anatomy is missing, but this may not appeal to our subjective understanding of reality and primal aesthetic. So, I challenge myself to portray these elusive worlds in a manner palpable and stimulating to our insufficient eyes. In my work I attempt to show the details our eyes are not sensitive enough to perceive in the dark and the events that we are perhaps not patient enough to watch unfold.

— From “Omniscient Lens,” the artist’s statement of Forest Pride ’16

Clear Writing

Awake

Waking in an aviary: I hear birds

Waking in an aviary: I hear birds

following instructions in the cheap manual,

saying their syllables,

adding unrecorded sibilants to avoid identification,

no check-mark on the life-list of an armchair birder

who listens into leaves inside the constructed forest.

Dozing into translation:

the message is not for me,

eavesdropping on captured nature, not

let us out or let us in,

just what the small throats have to say

before their bodies rise again

to bat against the netting’s screen of sky.

Rising through reverie: awaking

to the dome above

the floor beneath

the what-to-say

between.

Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

Letters

Rare MomentsLast July, during a rare trip to Vermont, we made a special effort to visit Marlboro College, which I attended for one year in 1950. It brought back many memories of a very special year for me—the academic community where I developed a serious interest in physics, attended a wonderful creative writing course with Charlie Jackson (right), enjoyed readings by Robert Frost and Sunday concerts by the Moyse family, plus joined the team to boil sap for maple syrup.

We had a grand welcome by admissions staff, and I mentioned that I have some rare photographs from 1950, taken with my Speed Graphic camera. I’ve had several 16x20 prints made for the college: Walter Hendricks escorting Robert Frost up to the dining hall for a reading (below), Mr. Frost reading and signing autographs, a picture of the campus in 1950. Hopefully you will find these of interest.

The gentleman at the desk is Charles (Charlie) Jackson, author of The Lost Weekend and The Sunnier Side, with whom I was honored to have a creative writing course. He came to Marlboro from his home in New Hampshire for a few days each week to teach, and stayed at the inn down the road, where that picture was taken. —Al LeBeau

The college is grateful for Al’s contribution, and plans to frame some of these beautiful prints for display. Send your photos and memories to pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

New Leaf

I just received the most recent edition of Potash Hill and was astounded. Thank you so much for your contribution to the college. It was always a pleasure working with you, and it’s so nice to have the magazine that represents my college looking so sharp.

—Michelle Wruck ’05

Finally got around to looking at the Fall 2014 issue of Potash Hill. Great job as usual...nice layout, good graphics, interesting stuff. I just happened to flip open the back cover, and there was a whole page spread on one of my very favorite persons in this world: Jean Boardman. Thank you and congratulations again! I can’t say enough in praise of Jean. Our daughter learned a lot from her (and Harry, too) when she was a Marlboro student and chambermaid at the Whetstone.

—John Ludwigson, father of Elli Ludwigson ’09

Congratulations on a really attractive magazine. I think the renovation is very nice.

—Rebecca Bartlett ’79, campus store manager

Potash Hill looks so great. I think you really threaded the needle between redesign and keeping the traditionalists happy.

—Todd Smith, chemistry professor

I love the new Potash Hill look—beautiful, classy, but not glitzy. However, Laura Tucker just is not me (Alumni News, page 42). I actively use my middle name and have since I was married almost 30 years ago (egads!).

—Laura Lawson Tucker ’77

Native Son

As eldest son of Marlboro’s founder, I feel very bonded to the college and that piece of the world there on South Road. My father bought the farm when I was a few years old, and I spent every summer there until I went off to college. So, seeing the Life magazine photographer’s photo of me sitting on the stone wall in your article “Marlboro and the Vermont Way of Life” (Potash Hill, Fall 2014) brought back many memories, and I enjoyed reading it.

However, I must take exception to the opening paragraph, and in particular misleading statements such as: “The Hendrickses were neither alone nor unusual in their purchase of a Vermont summer cottage; wealthy out-of-staters snatched up hundreds of such properties in the state throughout the 1930s, as Vermont’s reputation as a vacation destination amplified.”

My parents were not “wealthy out-of-staters.” That farm was bought with a small down payment and a mortgage, which my family struggled to make payments on through the years of the Depression and only paid off at the founding of the college. My father then deeded the farm to the college, so that it would have some assets to take out a mortgage on the Cerretani farm next door (Potash Hill, Winter 2011). It was all done on the proverbial “shoestring.”

My father came from a Norwegian immigrant family. His father died when he was a young boy, and his mother brought up six sons on the west side of Chicago. My mother likewise came from a poor, southern farm family, from Virginia. My father was the only one in his family who went to college, and that was due to the support and encouragement of the person he worked for at International Harvester, as an office boy. At Amherst College he met Robert Frost, who became a lifelong friend and mentor. All of this was only possible because of hard work and the support of people who believed in him.

After my father served in the army, Frost invited him to stay at his home in Franconia, New Hampshire, an indication of the dimension of their friendship. The year I was born, 1931, my parents and sisters were staying in the Frost cottage. Soon after this, Frost left Franconia— it was becoming too much of a tourist destination—and bought a farm in South Shaftsbury, Vermont. My father followed, finding the farm in Marlboro.

During the ’30s and early ’40s my father worked with neighbors, local farmers, to keep the fields mowed, hay in the barn, and for a while cows in the pasture and barn. The local people became part of our community of friends, together with summer people like the Whittemores and Christies. Every year a large garden was planted, and my mother put up green beans, corn, tomatoes, apple sauce, etc., in Mason jars, which would be taken back to Chicago for the winter, along with apples, carrots, and potatoes. The whole family worked at all of this, and my father, returning from teaching summer school in Chicago, would right away head out to the garden to pull weeds and hoe the rows of vegetables.

What I’m saying is that with both of my parents, there was never a great amount of money, a situation that was intensified by the years of the Great Depression. But they found in Marlboro a place with great creative energy and a strong connection to the land and to the community, something that I find remains today.

—Geoffrey Hendricks

Only Women Will Heal Me

Photos and Story by Brad Heck ’04 and Willow O’Feral ‘07

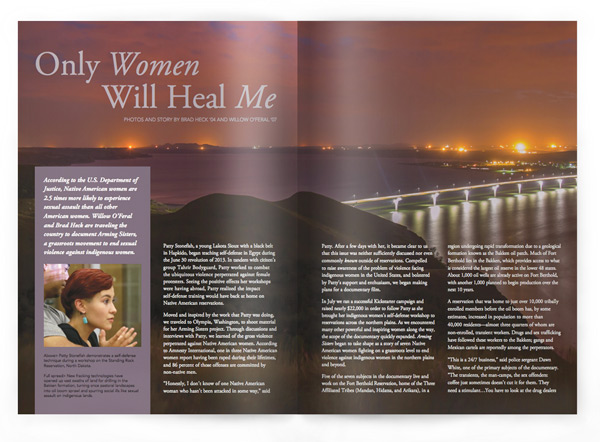

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Native American women are 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual assault than all other American women. Willow O’Feral and Brad Heck are traveling the country to document Arming Sisters, a grassroots movement to end sexual violence against indigenous women.

Patty Stonefish, a young Lakota Sioux with a black belt in Hapkido, began teaching self-defense in Egypt during the June 30 revolution of 2013. In tandem with citizen’s group Tahrir Bodyguard, Patty worked to combat the ubiquitous violence perpetrated against female protesters. Seeing the positive effects her workshops were having abroad, Patty realized the impact self-defense training would have back at home on Native American reservations.

Patty Stonefish, a young Lakota Sioux with a black belt in Hapkido, began teaching self-defense in Egypt during the June 30 revolution of 2013. In tandem with citizen’s group Tahrir Bodyguard, Patty worked to combat the ubiquitous violence perpetrated against female protesters. Seeing the positive effects her workshops were having abroad, Patty realized the impact self-defense training would have back at home on Native American reservations.

Moved and inspired by the work that Patty was doing, we traveled to Olympia, Washington, to shoot material for her Arming Sisters project. Through discussions and interviews with Patty, we learned of the gross violence perpetrated against Native American women. According to Amnesty International, one in three Native American women report having been raped during their lifetimes, and 86 percent of those offenses are committed by non-native men.

“Honestly, I don’t know of one Native American woman who hasn’t been attacked in some way,” said Patty. After a few days with her, it became clear to us that this issue was neither sufficiently discussed nor even commonly known outside of reservations. Compelled to raise awareness of the problem of violence facing indigenous women in the United States, and bolstered by Patty’s support and enthusiasm, we began making plans for a documentary film.

In July we ran a successful Kickstarter campaign and raised nearly $22,000 in order to follow Patty as she brought her indigenous women’s self-defense workshop to reservations across the northern plains. As we encountered many other powerful and inspiring women along the way, the scope of the documentary quickly expanded. Arming Sisters began to take shape as a story of seven Native American women fighting on a grassroots level to end violence against indigenous women in the northern plains and beyond.

Five of the seven subjects in the documentary live and work on the Fort Berthold Reservation, home of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara), in a region undergoing rapid transformation due to a geological formation known as the Bakken oil patch. Much of Fort Berthold lies in the Bakken, which provides access to what is considered the largest oil reserve in the lower 48 states. About 1,000 oil wells are already active on Fort Berthold, with another 1,000 planned to begin production over the next 10 years.

Five of the seven subjects in the documentary live and work on the Fort Berthold Reservation, home of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara), in a region undergoing rapid transformation due to a geological formation known as the Bakken oil patch. Much of Fort Berthold lies in the Bakken, which provides access to what is considered the largest oil reserve in the lower 48 states. About 1,000 oil wells are already active on Fort Berthold, with another 1,000 planned to begin production over the next 10 years.

A reservation that was home to just over 10,000 tribally enrolled members before the oil boom has, by some estimates, increased in population to more than 40,000 residents—almost three quarters of whom are non-enrolled, transient workers. Drugs and sex trafficking have followed these workers to the Bakken; gangs and Mexican cartels are reportedly among the perpetrators.

“This is a 24/7 business,” said police sergeant Dawn White, one of the primary subjects of the documentary. “The transients, the man-camps, the sex offenders: coffee just sometimes doesn’t cut it for them. They need a stimulant…You have to look at the drug dealers as business men…they’re going where the money’s at, and the money’s right here.”

Dawn is a pillar within the Fort Berthold community, one of the first women to receive the Champions of Public Safety in Indian Country Award (June 2014). We spent several nights riding along with Dawn as she patrolled the reservation. Dawn’s approach to her job requires a difficult balance of holding community members responsible for their actions while at the same time not taking their infractions personally and forgiving them the following day. There were few members she stopped whom she did not know by name, and many were related to her.

Dawn is also a survivor of sexual assault. Before becoming a police officer she was enrolled in the military, and while stationed in Germany she was sexually assaulted by another soldier. The trauma will “always be with me,” said Dawn. “It will never go away.” She described how the experience informs her work: “It does carry over to the job…being a survivor of [sexual assault] I know what that fear is, I know how it grips you…and it has helped, because I want to catch this person for them, I want to bring them to justice.”

Dawn is also a survivor of sexual assault. Before becoming a police officer she was enrolled in the military, and while stationed in Germany she was sexually assaulted by another soldier. The trauma will “always be with me,” said Dawn. “It will never go away.” She described how the experience informs her work: “It does carry over to the job…being a survivor of [sexual assault] I know what that fear is, I know how it grips you…and it has helped, because I want to catch this person for them, I want to bring them to justice.”

Bringing perpetrators of sexual assault to justice is difficult on a reservation, especially when the assailant is a non-enrolled member. The semi-sovereign state of Indian reservations requires coordination between tribal, state, and federal government agencies during investigations, and often in the case of a non-enrolled assailant, the burden of prosecution lies with the federal government. This results in a lot of jurisdictional pitfalls, and many cases get dropped before they ever come to trial. According the The Atlantic magazine, “In 2011, the U.S. Justice Department did not prosecute 65 percent of rape cases reported on reservations.”

Chalsey Snyder, an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes and another subject of the documentary, is working to increase the jurisdictional power of the Fort Berthold tribal government in cases of sex trafficking. She is writing tribal code that broadens the legal definition of sex trafficking and nearly triples the penalties and fines the Three Affiliated Tribes may enforce. She has named the tribal code “Loren’s Law” in honor of her friend and co-author of the code, who died tragically in a car accident last year.

Arming Sisters also focuses on Loreline LaCroix, a freelance advocate working with victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and sex trafficking. Although she has extensive experience in advocacy, she prefers being outside of the system, working one-on-one with her clients. Comprising one million acres, Fort Berthold is vast, and social services are seriously understaffed; sometimes Loreline is informally commissioned by tribal police officers and advocates to help handle the overflow of victims.

Arming Sisters also focuses on Loreline LaCroix, a freelance advocate working with victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and sex trafficking. Although she has extensive experience in advocacy, she prefers being outside of the system, working one-on-one with her clients. Comprising one million acres, Fort Berthold is vast, and social services are seriously understaffed; sometimes Loreline is informally commissioned by tribal police officers and advocates to help handle the overflow of victims.

Loreline has a long and traumatic history with assault herself, including being abused at age 2, molested at age 9, raped at age 12, and hospitalized by her first boyfriend and father of her oldest son at age 18. She has been in a stable and healthy marriage for the last 15 years, and views her work with other survivors as a form of restoration.

“I love what I do,” said Loreline. “I’m passionate about working with women…and only women will heal me. This work heals me. And I’ve got a lot of healing to do, so I have a lot of women to help.”

The pervasive violence against Native American women in this country, as witnessed by the subjects of Arming Sisters, is intolerable—yet it has become normalized. The primary goal of the documentary is to raise awareness of the issue and humanize the statistics by sharing the stories of survivors who are actively fighting for positive change. As explained by Lisa Brunner, an advocate for survivors and also one of the subjects of the film, “The first step is for it to be discussed at dinner tables across this country.”

Willow O’Feral and Brad Heck are currently working on editing and raising funds for post-production of Arming Sisters, and they extend their thanks to the Marlboro community for its ongoing support. For more information or to support the film, please visit: www.armingsistersmovie.com.

Direct cinema in a New Jersey free school Documentary films bring social issues to life, and for the first feature film of Amanda Wilder ’07 that issue is alternative education. “From the first day at Teddy McArdle Free School I could tell it would be an incredible thing to document, and would fit nicely with the kind of direct cinema I’d grown to love,” says Amanda. “There was a story unfolding before the camera, and a fascinating group of people, most of whom were children.” The resulting film, Approaching the Elephant, poses the vital question of how kids and adults learn to sort things out and live with each other in a school where the youngest student and the school’s director have equal say. In January, Amanda screened Approaching the Elephant at the Latchis Theater, in Brattleboro, and participated in a panel discussion with producer and film professor Jay Craven in New York City.

Documentary films bring social issues to life, and for the first feature film of Amanda Wilder ’07 that issue is alternative education. “From the first day at Teddy McArdle Free School I could tell it would be an incredible thing to document, and would fit nicely with the kind of direct cinema I’d grown to love,” says Amanda. “There was a story unfolding before the camera, and a fascinating group of people, most of whom were children.” The resulting film, Approaching the Elephant, poses the vital question of how kids and adults learn to sort things out and live with each other in a school where the youngest student and the school’s director have equal say. In January, Amanda screened Approaching the Elephant at the Latchis Theater, in Brattleboro, and participated in a panel discussion with producer and film professor Jay Craven in New York City.

Confluence

Sustainability requires gathering “tributaries of wisdom” and returning to a more ecologically enlightened relationship with the earth, says graduate faculty member Cary Gaunt.

By Cary Gaunt

The discharge pipe was just out of reach. By holding on to the branch of a draping willow tree I could almost position the beaker into the spewing effluent to get the sample needed for my research. Just when I was fully extended, the stream bank crumbled underfoot and I landed in the murky depths at the outfall of my hometown’s sewage treatment plant. Thus was my initiation into a lifelong vocation in sustainability. The year was 1977.

The discharge pipe was just out of reach. By holding on to the branch of a draping willow tree I could almost position the beaker into the spewing effluent to get the sample needed for my research. Just when I was fully extended, the stream bank crumbled underfoot and I landed in the murky depths at the outfall of my hometown’s sewage treatment plant. Thus was my initiation into a lifelong vocation in sustainability. The year was 1977.

Long before sustainability became an overused and misaligned buzzword—named one of the “jargoniest jargon” words by Advertising Age magazine and dismissed as “sustainababble” by the former president of the World Watch Institute—I started tracking its elusive path.

My journey started with love. To my parents’ chagrin (or perhaps relief), instead of obsessing over high school dating rituals, I fell in love with a place. Abrams Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, ran through our farm in Virginia and became my constant companion and endless source of fascination. I turned over rocks in search of crawfish, concocted teas from the wildflowers along its banks, laid on my back in the shallows during torpid August days, and built rafts that never floated. Mine was a reciprocal relationship cultivated through all of my senses—I tasted, smelled, heard, touched, and witnessed seasonal cycles and daily flows. My childhood curiosity prompted so many questions, many that still direct me today.

I am in the business of ecological restoration, mostly through watershed planning and management. What started as childhood exploration of cattail marshes and muskrat dens led me to rivers, lakes, and estuaries around the country. The questions always at the back of my mind are “What are the root causes of unsustainability, and what are the most effective ways to restore ecosystems and the human communities with which they are associated?” These are not just my questions, but those of most people working with ecological restoration. When we look upstream, literally or figuratively, we ultimately find out-of-compliance industrial dischargers, sprawling corporate and commercial enterprises, overloaded wastewater treatment plants, concentrated animal feeding operations, gigantic “McMansions,” and so much more.

If I had met my colleague Mark McElroy during the height of my ecological restoration consulting career, I might have looked upstream and pointed my finger of blame at him. Mark was working for what I perceived as “the other side,” consulting with big businesses on their management practices. He was not thinking about upstream or downstream impacts, until quality-of-life decisions caused him to relocate with his family to Vermont in his late 30s. From the rolling hills of Hartland, Mark’s view began to shift. His thinking was further influenced by his association with environmental luminary Donella “Dana” Meadows, author of Limits to Growth, who also took up residence in his town. “Through discussions with her, I gradually came to better understand the real meaning of sustainability and the extent to which most of what passes for mainstream practice in both business and society was falling short of it,” Mark recalls.

In 2013 our distinct paths found a confluence at Marlboro College, where we were hired to teach the two central sustainability courses in the MBA program. Ecologists consider the confluence an area of enrichment that occurs at the meeting place of contrasting habitats. When waters from two different sources flow together, for example, the resulting nutrient soup often provides immensely fertile habitat. Wisdom teachers also note the creative ferment of the confluence, or “middle way.”

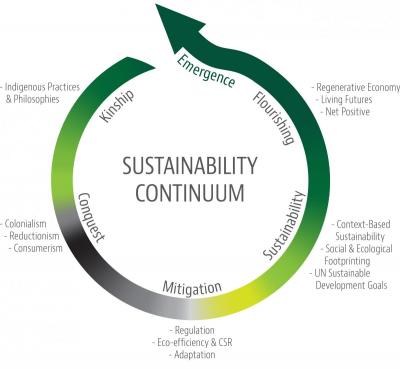

Marlboro is a place imbued with smart and engaged students, who asked for clarity amidst a world of “sustainababble.” From the confluence of our distinct perspectives, and with the skillful facilitation and wisdom of two other colleagues on the MBA faculty, Bill Baue and Pat Daniels, we created the Sustainability Continuum, a business leadership framework that explains the evolution of sustainability and its important normative developments.

Marlboro is a place imbued with smart and engaged students, who asked for clarity amidst a world of “sustainababble.” From the confluence of our distinct perspectives, and with the skillful facilitation and wisdom of two other colleagues on the MBA faculty, Bill Baue and Pat Daniels, we created the Sustainability Continuum, a business leadership framework that explains the evolution of sustainability and its important normative developments.

The Sustainability Continuum identifies six distinct phases of sustainability thought and practice (see figure, right). Although presented as a chronology, we consciously shaped the continuum as a circle to reflect the evolutionary emergence of sustainability consciousness and action, its relationship to ecological cycles and goals of wholeness, and to indicate the actual and desired direction for its unfolding. The trajectory is neither stepwise nor linear. Rather, many of the stages presented in the continuum occur concurrently. Individuals, organizations, and businesses can locate themselves on the continuum and use its framework for sustainability planning and action. It has already proven to be an excellent tool for organizing our curriculum, and teachers throughout the MBA program are using it in their classes.

We initiated the Sustainability Continuum in the deep past, what we call the Kinship stage, where humans were deeply embedded in their places and connected to the natural world in relational and participatory ways, often in accord with ecological cycles. This stage represents an indigenous way of knowing, described by Native American educator and Tewa Indian Gregory Cajete as one that is rooted in place and based on “the perception gained from using the entire body of our senses in direct participation with the natural world.” It is far broader than the narrow view of Western science and business management, because it includes spirituality, community, creativity, and dynamic participation with the natural world based on an ancient covenant. While some have called into question the environmental practices of ancient cultures, indigenous worldviews based on principles of participation, relationship, interdependence, animism, and kinship comprise a “perceptual wisdom” that is essential for sustainability.

The foundation for many of today’s unsustainable ways surfaced in the Conquest stage, which describes the shift away from interdependence with nature toward exploitation of nature—in which previously sacred relationships became commoditized and privatized, and the natural world became reduced to smaller and smaller parts suitable for study and sale. This period was marked by increased alienation from the natural world, a growing anthropocentric worldview, organized and aggressive colonialism, and the advent of consumerism, including the growth and extractive economies we still have in place today. This is arguably the stage where most businesses and MBA programs focus their emphasis in order to bolster the bottom line and shareholder profits—it is discouraging how many examples of this stage are at work today. We make our students aware of them, but consciously emphasize a new way of doing business.

The foundation for many of today’s unsustainable ways surfaced in the Conquest stage, which describes the shift away from interdependence with nature toward exploitation of nature—in which previously sacred relationships became commoditized and privatized, and the natural world became reduced to smaller and smaller parts suitable for study and sale. This period was marked by increased alienation from the natural world, a growing anthropocentric worldview, organized and aggressive colonialism, and the advent of consumerism, including the growth and extractive economies we still have in place today. This is arguably the stage where most businesses and MBA programs focus their emphasis in order to bolster the bottom line and shareholder profits—it is discouraging how many examples of this stage are at work today. We make our students aware of them, but consciously emphasize a new way of doing business.

One summer day in 1969, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River began to burn, capturing the attention of a nation waking up to the serious and palpable damages caused by a rampant Conquest stage of human activity. A month later, Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. Images of earth from space showed for the first time the boundaries of a finite planet. The confluence of these memorable events, and many more, sparked the dawn of a formal U.S. environmental movement—on April 22, 1970, the first Earth Day celebration was held, and later that year the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed.

We mark the Mitigation stage by the establishment of regulatory controls and the rise of eco-efficiency concepts and adaptation initiatives based largely on engineering and other technological approaches. The creation of the EPA was symbolic of this era, and was heralded by a creative burst of environmental regulations—the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Ocean Dumping Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Energy Policy and Conservation Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, and the Superfund Program—all in the first decade.

The emphasis of these important efforts was to reduce and/or adapt to the unwanted effects of consumerism by setting limits or increasing efficiency—steps in the right direction, but still not sustainability in the more rigorous sense of the term. My predecessor at Marlboro, sustainability thought leader John Ehrenfeld, sees these efforts as “merely a Band-Aid that masks deeper, cultural roots of our sustainability challenge.” In his seminal book Sustainability by Design, John writes, “Hybrid cars, LED light bulbs, wind farms, and green buildings, these are all just the trappings that convince us that we are doing something when in fact we are fooling ourselves and making things worse.”

The emphasis of these important efforts was to reduce and/or adapt to the unwanted effects of consumerism by setting limits or increasing efficiency—steps in the right direction, but still not sustainability in the more rigorous sense of the term. My predecessor at Marlboro, sustainability thought leader John Ehrenfeld, sees these efforts as “merely a Band-Aid that masks deeper, cultural roots of our sustainability challenge.” In his seminal book Sustainability by Design, John writes, “Hybrid cars, LED light bulbs, wind farms, and green buildings, these are all just the trappings that convince us that we are doing something when in fact we are fooling ourselves and making things worse.”

I have experienced this disconnect between sustainability intention and result throughout my career, most recently as a consultant for the Boston Green Ribbon Commission. I was charged with assessing the progress of the city’s colleges and universities in achieving the ambitious carbon reduction goals of Boston’s Climate Action Plan. All of the schools were taking impressive steps, from building LEED-certified buildings to using sustainable food options for campus dining. Yet all of these were conducted in the shadow of growth. Each university was committed to growing its student population and campus size, effectively overwhelming its positive steps.

Despite decades of well-meaning mitigation efforts, the economics of growth and excess have created conditions where the nation as a whole is not achieving its sustainability goals. Environmental conditions continue to decline, and threats to our natural world appear to be relentless and expanding. People across sectors increasingly ask, “What’s next? How do we respond?” It is from this inquiry that the effort to develop sustainability metrics emerged.

What we call the Sustainability stage responds to the business adage “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” The Sustainability stage is where business practices revolve around the idea that there are social, economic, and environmental thresholds, locally and globally, that must be taken into account when attempting to manage or assess the effects of human activity. “Authentic sustainability” will only occur when resource use or waste generation are measured against clearly defined place-based limits, such as the amount of water in local aquifers, or the amount of carbon the atmosphere can safely absorb.

“If you just look at the measurements of what you are doing and don’t tie it back to reality on the ground, in terms of resources that are available or the social investments that are necessary, then you’ve answered some questions,” says Mark McElroy. “But you haven’t answered the question of ‘are you sustainable?’” Mark had started working on measuring sustainability performance with his mentor Dana Meadows shortly before her death in 2001, and he decided to continue this work for his doctoral dissertation. He created a business-focused sustainability accounting system called Context-Based Sustainability (CBS), which has further evolved into the MultiCapital Scorecard (MCS).

“If you just look at the measurements of what you are doing and don’t tie it back to reality on the ground, in terms of resources that are available or the social investments that are necessary, then you’ve answered some questions,” says Mark McElroy. “But you haven’t answered the question of ‘are you sustainable?’” Mark had started working on measuring sustainability performance with his mentor Dana Meadows shortly before her death in 2001, and he decided to continue this work for his doctoral dissertation. He created a business-focused sustainability accounting system called Context-Based Sustainability (CBS), which has further evolved into the MultiCapital Scorecard (MCS).

With Mark’s support, two popular Vermont businesses are stepping out as leaders through their pioneering work implementing these sustainability metrics. Both Cabot Cheese and Ben & Jerry’s are using these approaches to “take sustainability literally,” by exploring actual resources used or impacted in manufacturing, such as water and climate, measured against what is truly available in their manufacturing areas and in their supply chains. In addition, they include a human component and consider factors such as livable wages, social activism, and gender parity.

Sustainability metrics are essential steps in the sustainability journey, yet something else is clearly needed—such was the conclusion of the 2003 Chesapeake Futures report, which provided a 20-year retrospective of restoration efforts and an ambitious look forward. While acknowledging the important contributions of conventional environmental protection approaches, the report concluded that we could not regulate, monitor, measure, or model ourselves out of the problem, or find a technological fix. The report called for the cultivation of a new ethic: the ecologically enlightened citizen.

I became seized by the underlying recommendation of the Futures report, because it captured my own beliefs and the central theme repeatedly heard in sustainability circles—how do we cultivate the ecologically enlightened citizen? It fueled a research inquiry that eventually became my doctoral dissertation and dramatically changed the trajectory of my work. I began shifting my gaze from the Mitigation and Sustainability stages to something much more difficult to quantify. I gathered tributaries of wisdom from sources that were new to me—psychology, religion, spirituality, and other humanities and social sciences—and some that were a homecoming, especially deep exploration of the natural world and contemplative traditions. Even more, I sought out the wisdom of lived experience from individuals who are ecologically awakened and committed to sustainability—leaders and ordinary citizens who modeled the kinds of changes we seek.

In Sustainability by Design, John Ehrenfeld calls these kinds of changes “sustainability-as-flourishing.” He describes them emerging from profound shifts in human consciousness and behavior, from a view of ourselves of “Having” to one of “Being,” from one of “Needing” to one of “Caring.” The sustainability role models I study for my research embody in many ways the new ethic John imagines. Of course they are intellectually engaged in the issues, from the science of climate change to the complexities of renewable energy. More, however, they speak of creating new stories of how to live and inhabit our places, and how to fit into the larger earth story.

In Sustainability by Design, John Ehrenfeld calls these kinds of changes “sustainability-as-flourishing.” He describes them emerging from profound shifts in human consciousness and behavior, from a view of ourselves of “Having” to one of “Being,” from one of “Needing” to one of “Caring.” The sustainability role models I study for my research embody in many ways the new ethic John imagines. Of course they are intellectually engaged in the issues, from the science of climate change to the complexities of renewable energy. More, however, they speak of creating new stories of how to live and inhabit our places, and how to fit into the larger earth story.

These sustainability role models embody the Flourishing stage by spending time getting to know the resources and beings of their places, using all of their senses. They are gardeners, or participate in ecological restoration. Others are naturalists or artists informed by nature. All are explorers—intellectually curious and wanderers on the land. They use words like beauty, wonder, awe, and love to describe the earth and their relationship to it. Many consider the natural world to be imbued with spirit, and therefore sacred. By being deeply rooted in their places, they intuitively considered environmental and social thresholds in their decision making. They had, whether “born in the groove” like me on the banks of Abrams Creek or “converted later in life” like my colleague Mark McElroy, begun a return to the Kinship stage of sustainability consciousness and action, but with a modern approach.

The Flourishing stage demands a human relationship with place that is premised on reciprocity and embodied through actions that contribute more to the natural and human communities than they take from them. Flourishing enterprises might restore their grounds with locally generated organic compost and bee-friendly native plants, power their buildings with fully renewable resources and give some excess back to the grid, or support every employee’s growth and potential.

Like the Sustainability stage, on-the-ground implementation of the Flourishing stage is in a nascent state, operationalized at a few small, local businesses, farms, and residences, and partially implemented by some large businesses. Widespread implementation has a long way to go, and yet the vision is compelling, necessary, and gaining traction.

Back in 1977, when I plunged into the effluent outfall in Abrams Creek, my hometown sewage plant was a significant polluter—we would place it squarely in the Conquest stage, oblivious to environmental and social concerns. Today, a new facility provides state-of-the-art wastewater treatment and seeks to be an innovative leader in green energy production, processing municipal sludge and organic waste into methane gas. These new ways of doing business demonstrate the Sustainability Continuum in action and provide glimmers of the Flourishing stage that is possible. The great challenge of businesses today— and really the challenge confronting all of us—is not only to comply with natural and human limits, but to consciously improve the systems in which we live and work.

Cary Gaunt has spent most of her career leading watershed restoration efforts around the country for Science Applications International Corporation, and was lucky to spend much of her time working on her home watershed, the Chesapeake Bay. She is now a faculty member in Marlboro’s MBA in Managing for Sustainability program, where she teaches Exploring Sustainability and conducts research on ecologically enlightened leadership and ways businesses can enter the Flourishing stage of the Sustainability Continuum.

Business Doing Good When John Tedesco MBA ’12 was working on his Capstone Project, he was the safety and environmental manager at Green Mountain Power (GMP), where he has worked for nearly 10 years. “I was deeply involved in GMP’s corporate social responsibility reporting (CSR), and I wanted to take our commitment further.” He chose to focus on how GMP could meet the rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency spelled out by the nonprofit B Lab. It was therefore gratifying for John when, in December, Green Mountain Power was recognized as the first utility company in the world to become a Certified B Corp. “Regulated monopolies tend to move at a glacial pace when it comes to innovation and forward thinking,” says John. “GMP has shown that you can thrive within the regulated sector and lead the way. Basically it shows the world that all businesses can do good.”

When John Tedesco MBA ’12 was working on his Capstone Project, he was the safety and environmental manager at Green Mountain Power (GMP), where he has worked for nearly 10 years. “I was deeply involved in GMP’s corporate social responsibility reporting (CSR), and I wanted to take our commitment further.” He chose to focus on how GMP could meet the rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency spelled out by the nonprofit B Lab. It was therefore gratifying for John when, in December, Green Mountain Power was recognized as the first utility company in the world to become a Certified B Corp. “Regulated monopolies tend to move at a glacial pace when it comes to innovation and forward thinking,” says John. “GMP has shown that you can thrive within the regulated sector and lead the way. Basically it shows the world that all businesses can do good.”

“The world’s harp has but a single string”

By Amer Latif

As a student and teacher of religion, I see a certain common thread through Islamic teachings that is echoed in Islamic practice and ritual. To put it simply, it is the idea of unity—the unity of creation, but specifically god’s unity. In Islam this is called tawhid, the affirmation or the assertion that god is one. The word tawhid comes from the Arabic root for “one,” which is wahid, and is a verbal noun that means, literally, “making one.”

As a student and teacher of religion, I see a certain common thread through Islamic teachings that is echoed in Islamic practice and ritual. To put it simply, it is the idea of unity—the unity of creation, but specifically god’s unity. In Islam this is called tawhid, the affirmation or the assertion that god is one. The word tawhid comes from the Arabic root for “one,” which is wahid, and is a verbal noun that means, literally, “making one.”

I think that it is important for people to recognize that in Islamic imagination, all of the prophets of the Judeo-Christian tradition, starting with Adam all the way down to Jesus, are also considered prophets. Growing up Muslim myself, these prophets were very large figures in our imaginations. Stories were told about them, perhaps as often as, if not more often than, stories about the life of Muhammad. It’s also important to remember that according to the Koran, Islam is not a new religion. The Koran teaches that Islam is a renewal of the one religion, sent by God to all people in their own language via one of their own.

The Koran asserts that god has renewed the same message for each community, and the message is simple: There is no god but god, la ilaha illallah. This phrase is called “the words of tawhid,” and Muslim scholars refer to it as “the first witnessing.” The Islamic affirmation of faith goes on to say that “there is no god but god and Muhammad is the messenger and servant of god.” It thereby adds the manifestation of Islam in sixth-century Arabia to the one message sent to all communities. So from the Islamic perspective, Jews say, “There is no god but god and Moses is the messenger of god,” and Christians say, “There is no god but god and Jesus is the messenger of god.”

In Arabic, allah is not just a Muslim god, as Zeus is a Greek god; rather it is “the god.” Arabic Jews and Christians used the same word to refer to god, so it is attested, in earliest translations of the bible into Arabic. In Jewish translations from Hebrew to Arabic, elohim is translated as allah. Currently, some translators who work with Christian missions also argue that it should be translated in that fashion. In today’s polemical atmosphere, what is lost is this historical continuity and similarity between these two traditions. Grasping this can give good insight into the possible experience of 1.5 billion people and how they relate to the world.

I am reminded of a poem by Rumi:

“All the tasks of the world are different, but all are one…The whole world is indivisible, the world’s harp has but a single string.”

Amer Latif is professor of religion at Marlboro College. This editorial is excerpted and adapted from his talk in November titled “In the name of the one who has no name: Constructing and deconstructing god in Islamic ritual practice.” Find further discussion of these ideas.

On & Off the Hill

There must be a Marlboro: President Ellen’s legacy

By Peter T. Mallary ’76

I remember Ellen’s inauguration as Marlboro College’s eighth president very clearly. Her address was powerful stuff. She just seemed to get it about Marlboro. Surely her many years of a real and deeply felt connection to Vermont helped lead her to an appreciation of what she called the “beautiful village on the hill.” But it was more than that. She clearly saw why Marlboro College matters. In her speech she summed up a vision of, and mission for, the college that matched our long held self-image: commitment to community and intellectual accomplishment. Her poignant refrain echoed, “There must be a Marlboro.” This June, 11 years later, Ellen McCulloch-Lovell leaves the college with that commitment refreshed and with the institution demonstrably stronger.

What Ellen brought us that day was exciting. Her résumé was impressive; Bennington College, Vermont Council on the Arts, 10 years as Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy’s chief of staff, high-level service to both the president and the first lady in the Clinton White House, and most recently heading the Veteran’s History Project at the Library of Congress. As her friend Hillary Clinton once advised her, Ellen had learned “how to pull the levers” in government and beyond.

Ellen recalls sitting in her office and receiving a call from a head-hunting firm asking her for her thoughts about Marlboro College. Assuming they were interviewing her for background information she offered her warm impressions of the college, knowing the place because of summer visits to the music festival and professional relationships with some faculty. The caller then came to the point. What about Ellen McCulloch-Lovell as a candidate for the job of president of Marlboro?

“Absolutely not!” She had no experience in the academic world, she said, and her husband Chris would have to leave his tenured university position. Ellen did offer to help them find some other candidates. But they were persistent. A few calls later—homesick for Vermont and with a sense that this was a leadership challenge she might want to take on—she threw her résumé in the ring.

Ellen has presided over Marlboro College with warmth, dedication, and passion. She leaves behind a campus strengthened by her foresight in financial planning, aware of the challenges facing us in the market of higher education, and engaged as a community in continually articulating and refining our vision. I will miss her enthusiastic leadership, her ever-present support of our students (including her frequent presence in the audience at dance performances), as well as her warm friendship.

—Kristin Horrigan, dance faculty

“I fell in love,” she says. “I drove up the hill and said ‘I’m home. I’ve found a true intellectual community that also really cares about people’s participation in the world, and I want to be here.’” And as she left the on-campus interviews—watching snow fall on Potash Hill—she knew this was a job she wanted.

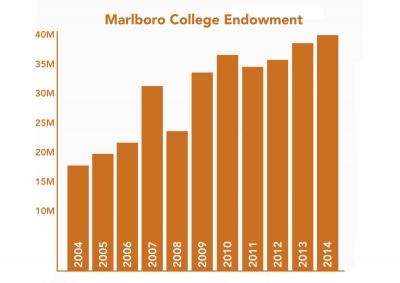

What Ellen leaves behind at Marlboro is impressive. Fiscally the college has never been stronger. During Ellen’s tenure the endowment has grown from $16 million to more than $40 million (see chart right). The endowment per student meets the highest national standards. It also leaves the college with the ability to commit substantial resources to broadcasting Marlboro’s unique story far afield. All this has been accomplished in spite of international economic trauma. Though she is quick to give her predecessors credit for building an endowment foundation, there is no question that this president has brought special skills to the art of donor relations and fundraising in general. She has a gift for telling the college’s story—and convincing people that they want to be a part of that story.

What Ellen leaves behind at Marlboro is impressive. Fiscally the college has never been stronger. During Ellen’s tenure the endowment has grown from $16 million to more than $40 million (see chart right). The endowment per student meets the highest national standards. It also leaves the college with the ability to commit substantial resources to broadcasting Marlboro’s unique story far afield. All this has been accomplished in spite of international economic trauma. Though she is quick to give her predecessors credit for building an endowment foundation, there is no question that this president has brought special skills to the art of donor relations and fundraising in general. She has a gift for telling the college’s story—and convincing people that they want to be a part of that story.

I knew from the start that Ellen would bring uncommon grace, clarity, and collegiality to Marlboro. Throughout, she has been a champion of the college and a true friend to the community, near and far, celebrating with us our core mission and accomplishments and inspiring confidence in Marlboro’s future.

—Jim Tober, retired economics faculty

Academically, as well, the college has never been stronger. When Ellen arrived, she saw a number of challenges. A generation of senior faculty was about to retire without a proper retirement program in place. There was also a need to increase faculty salaries. So she raised $12 million to endow the Fund for Inspired Teaching, designed to address these issues. And new faculty came, mentored by long-serving faculty and staff.

“We have very strong new faculty who are really embracing the Marlboro model of student-driven learning and working across disciplines. When a faculty member says—as they typically do at Marlboro—‘my students are my colleagues,’ that’s very unusual in higher education. They set very high expectations that students want to meet. We have to continue to advocate for and explain our model; we open students’ minds to other ways of learning and the expanse of discovery.” As she leaves, Ellen is establishing the President’s Fund for Marlboro’s Future in order to further recognize and endow the faculty and staff’s commitment to the Marlboro model— personal, intensive, and demanding.

The future of the graduate and professional studies program has been a particular focus of Ellen’s, as she worked to build a bridge between the graduate and undergraduate campuses both practically and philosophically. She launched the program in nonprofit management, which now includes certificate and master’s programs, leadership and board training.

For me, Ellen’s legacy will be the many instances over the past ten years where she modeled a remarkable ability for deep listening and attentiveness to the many different and, at times, competing voices within our community.

—Amer Latif, religion faculty

“The graduate center provides a way to expand our offerings for working adults, using a hybrid model that blends intensive, in-person residency with online learning. The programs have evolved closer to the heart of the college on the hill: we are one college serving many kinds of students.” A growing number of undergraduate students have gone on to earn professional certificates or master’s degrees through the graduate and professional studies programs. “It has also been a great opportunity for a higher profile in the region.”

Ellen talks about some of the things that surprised her about the job. One has been her interest in the physical plant and the appearance of the campus, both on the hill and downtown.

“One of the things people always remark about Marlboro College is that it is beautiful. I often describe it as a New England hill village. It’s an apt metaphor, with our Town Meeting and our smallness and our interdependence. It goes to the core of Marlboro’s identity. It has given me very deep pleasure to make it more beautiful.”

Remarkable strides have been made in the past decade. Early in her tenure, Ellen had the pleasure of presiding over the dedication of the Serkin Center for the Performing Arts. In 2006 the Gib Taylor metalworking studio opened, and in 2008 the Total Health Center. In 2011 the core of the campus received a landscaping makeover, and in 2012 the community greenhouse opened, followed by new classroom spaces downtown.

Ellen has added 114 acres and two other buildings to the undergraduate campus in her time here. As she prepares to leave, ground has been broken for the Snyder Center for the Visual Arts, scheduled to open this fall. Her personal vision and fundraising fingerprints are all over most of these projects—just further examples of the network of support for the college that she has built, with “lots of help from others.” Those others include the Marlboro Music School and Festival, based on the undergraduate campus in the summer, a relationship that Ellen has treasured.

Another surprise Ellen notes is how much she came to care about the students, and how much she worried about them.

“I didn’t realize how powerful it would be, watching their struggles and their triumphs. I can’t keep them safe, and I can’t make sure they always make the right decisions, but I want them to have the tools to make good decisions and to have good lives.”

My fondest memories are of Ellen’s personal commitment to Marlboro—a kind word in times of joy and sorrow, her gracious presence in a senior oral, and her ready acceptance of my spontaneous request to read a poem in an Environmental Studies class session for accepted students.

—Jenny Ramstetter, biology faculty

There have been storms to weather—literally. Ellen recalls the night of the 2008 ice storm, when the woods around the president’s house rang with cracks that “sounded like rifles” as trees and limbs fell. That morning Ellen was one of just a few people able to get to campus. She opened the kitchen and ended up flipping pancakes, enlisting students to help.

“We were two and a half days with no power. Nearby faculty and staff walked to campus to help. Dan Cotter and his crew moved generators from building to building.” Ellen recalls the resilience of the students as the power outages went on, finally leading to their being sent home early for the December holidays.

Following that storm, a generous donor provided funds for a generator to cover parts of the center of campus, and Ellen would need it. In 2011 Tropical Storm Irene brought high winds and rain—11 inches in 24 hours. Roads washed out, and the campus was cut off for three days.

“We had new students back from their Bridges orientation trips. The sense of isolation was really extreme. Keeping everybody fed was a challenge. But the community was once again resilient. We ate a lot of rice and beans.”

Ellen has taken an active interest in every area of the college: all of its curriculum, all of the many faculty and staff hires, its alumni, friends, and donors, the Outdoor Program, Town Meeting, long range planning, and current culture. The energy she has brought to all of this is humbling not just because of how hard it is but because of the sincerity of her concern for all these activities and constituencies.

—Tim Segar, visual arts faculty

Ellen has tackled other crises as well. Perhaps most importantly she has become a national champion of the liberal arts, seeking and achieving a high profile concerning the widespread challenge to what one faculty member calls “the liberating arts.” There has been a lot of debate and a lot of pressure from the White House on down, especially now with greater vocational focus and the monetization of the value of higher education.

“It can be very hard to struggle against the trend—to stand up for liberal education, the broad knowledge and academic skills that the Plan of Concentration is all about. How do we adapt, and how do we fight? How do we continue to present our strengths? I am committed more strongly than ever to finding these answers. I believe in a liberal arts education more fervently than when I wrote that inaugural address. I’m lucky to have the support of trustees who share that belief.”

Ellen chastises herself for not seeing emerging enrollment challenges coming sooner. But she extolls the virtue of collaborations with faculty, staff, students, and trustees to meet these challenges. “A wonderful we,” she says. “Everything I’ve been able to do was with the support of others.” Mostly, she seems at peace with her tenure and a bit nostalgic as she contemplates finishing up.

“I don’t think I fully realized the great pleasures of being part of an intellectual and creative community,” she says. “I will remember moments like giving graduate students diplomas while their children cheer them on, or a recent Work Day spent cleaning up the campus while students talked about their interpretation of Dostoyevsky. It’s a very heady place.”

From the final phrases of Ellen’s inaugural address comes her vision of Marlboro writ simple and clear: “There must be a Marlboro: a place of beauty; a clearing in the forest made for contemplation; a space to create and to become.” Ellen McCulloch-Lovell has made another generation of this dream possible.

Peter Mallary is a Marlboro trustee and the father of a graduate, Rebecca Mallary ’11.

I have had the pleasure of working with Ellen on everything from grant writing to revisiting the role of the dean of faculty. In every instance I have found her wise, compassionate, and creative. Each spring at commencement, Ellen greets every graduating senior as they cross the stage—what may not be visible from down on the floor is her connection to every one of those 70-odd students. This connection is an expression of her grace and warmth, qualities so intrinsic to her demeanor that it is virtually impossible to imagine her without them.

—Seth Harter, Asian studies faculty

Eleven Years with Ellen

2004

2004

- Inauguration as eighth president of Marlboro College

- Bart Goodwin becomes chairman of board

2005

- Marlboro ranked #1 by Princeton Review for “Professors Bring Material to Life”

- Jerome I. Aron Fund established to support student-faculty collaboration

- Ellen works with community to articulate Four Goals to Guide Marlboro

- Dedication of Serkin Center for the Performing Arts

- Chris Lovell starts Community Trails Day to maintain OP trails

2006

- Dedication of Gib Taylor metalworking studio

- Center for Creative Solutions established to respond to community planning needs

2007

- Marlboro MBA in Managing for Sustainability launched

- 60th Anniversary Fund for Inspired Teaching created

2008

- Grand opening of Total Health Center

- Bridges orientation programs for new students established

- Dedication of Gander Center for World Studies

2009

2009

- Marlboro rides out economic storm

- College launches energy efficiency measures with U.S. Department of Energy grant

2010

- Task Force on the Future makes recommendations

- First alumnus board chair, Dean Nicyper ‘76

- Graduate school launches program in nonprofit management

2011

- Center of campus upgraded with walking paths and stone walls

- Marlboro rises to challenge of Tropical Storm Irene

- Global opportunities supported by Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation

Marlboro offers dual degree programs through graduate school

Marlboro offers dual degree programs through graduate school- Summer programs for high school students launched

- Margaret A. Cargill Foundation grant supports environmental initiatives

2012

- Movies from Marlboro launched

- Community greenhouse grand opening

2013

- Beautiful Minds Challenge established

2014

- Strategic Plan for Marlboro’s future approved by trustees

- Snyder Center for the Visual Arts groundbreaking

- Cottages renovated with Marlboro Music School

John Rush animates economics

“I wanted to be somewhere where teaching would be valued, and to really have the opportunity to know my students,” says John Rush, a professor of economics who joined the Marlboro faculty in August. Before coming to Marlboro, John taught at the University of Hawaii, where he had more than a hundred students in one class and found it hard to make a significant connection with them. He is excited to be at Marlboro, which he considers “an ideal place to be a teacher and to work with students.”

“I wanted to be somewhere where teaching would be valued, and to really have the opportunity to know my students,” says John Rush, a professor of economics who joined the Marlboro faculty in August. Before coming to Marlboro, John taught at the University of Hawaii, where he had more than a hundred students in one class and found it hard to make a significant connection with them. He is excited to be at Marlboro, which he considers “an ideal place to be a teacher and to work with students.”

John grew up in northern California and received his bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s in management from Whitworth University, in Spokane, Washington. He then went on to get his M.A. and Ph.D. in economics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where he researched the influence of natural disasters on poverty and inequality in developing countries.

“I have a lot of interests,” says John. “My research up to now has been focused on natural disasters and how they affect economic development, but I’ve also been really interested in the history of economic thought, learning more about the originators of the big ideas we use in economics. Gold rushes are something I’ve studied a little bit about and find really interesting to look at from an economic perspective.” He also wants to further explore the philosophical concept of “weakness of will,” a subject he finds very relevant to the foundations of economic theory.

John finds that his research helps inform his teaching in many ways, whether that’s using natural disasters to help illustrate economic ideas in a vivid and accessible way, or reading broadly to explore new connections with other disciplines. He has taught economics at the University of Hawaii, Kapiolani Community College, and LCC International University in Lithuania, but finds Marlboro especially conducive to his interdisciplinary leanings.

“One of the things I like about Marlboro is that I can read things that I wouldn’t necessarily be justified in reading for my job at other places,” he says. “There are many kinds of questions related to economics that have to do with assumptions and individual choice. At Marlboro I am free to explore these ideas without having to lay out a clear research agenda, and I think it helps my teaching. I am more informed about things that are interesting to me and important for students to think about.”

John taught two classes last fall, International Economics and Economics: Principles and Problems, the latter of which included Robinson Crusoe on the reading list. Although he asserts that economists have used Daniel Defoe’s classic to illustrate certain principles for centuries, it is less common to include the novel in an economics class, as he does. In his class on economic development he includes Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. “That one was more my own idea,” he says. “I think it is a really excellent novel in terms of development and ethics.”

John cites Scottish philosopher Adam Smith as one of the authors that has most influenced his thoughts, not only his famous Wealth of Nations, but also The Theory of Moral Sentiments. “This much smaller book gives you a good background and understanding of where Adam Smith is coming from, in terms of what he believes about people and about the nature of human beings. It provides an interesting context to his other economics work.”

He is excited about building on the economics curriculum at Marlboro, so ably guided by retired professor Jim Tober since its inception. For John it is an opportunity to think about economics in a different way, in a broader and more interdisciplinary context, and to create a program that is responsive to the interests of students. He finds the small classes and close collaborative relationships with students at Marlboro a huge advantage in this regard.

“You can tailor classes if students are interested in a particular thing—when it’s a huge class it’s harder to do that because everyone is interested in a lot of different things,” he says. “Also, I can keep better track of my students—I can notice early on if someone is struggling. It’s much easier to be proactive if you have a relationship with students.” In economic terms, which are only fitting, John finds that Marlboro’s faculty-student ratio has a direct impact on the “marginal product.” “The quality of economic knowledge I can produce per student in a small class is larger than what I could produce for a student in a large class.”

Watch the next Potash Hill for a profile of Jean O’Hara, a new faculty member in theater who joins us on campus this spring semester.

EEI brings environmental leadership on the road

“Marlboro College has remarkable and deep roots in Vermont,” says Kyhl Lyndgaard, professor of writing and director of environmental studies at Marlboro. “But to paraphrase nature writer John Daniel, we can also say words in favor of rootlessness, at least in the form of a semester on a bus.”

Kyhl was referring to Marlboro’s new partnership with the Expedition Education Institute (EEI) to adopt innovative, bus-based programs pioneered by EEI into Semester at Marlboro offerings. Together, the two organizations will provide an undergraduate and gap-year pilot semester in the fall of 2015, and are in discussion about the possible launch of a new Master of Arts in Teaching for Ecological Education and Leadership.

EEI comes from more than 40 years of higher education rooted in direct experience, independent learning, and immersion in the natural world, as practiced by the former Audubon Expedition Institute. Participants live and learn together in an experiential learning community, traveling in a custom-retrofitted school bus. Students and faculty eat, sleep, and study outdoors within a specific bioregion as they explore local and global environmental challenges faced by communities and ecosystems.

“EEI is entirely field based but still interdisciplinary, which is a hallmark of environmental studies at Marlboro,” says Kyhl, who points out that with many alumni common to EEI and Marlboro, the fit was clear even before the partnership became official. “EEI allows for the experiential and self-directed learning that has long been central to the Marlboro model, but is mobile.”

The fall 2015 semester will take place in the Adirondacks and Appalachia, with a focus on energy and climate justice, and will be open to gap-year students, Marlboro College students, and visiting undergraduate students from other institutions. Spring 2016 will find the bus in the southeastern states, with a focus on sustainable food and farming. For more information, go to: marlboro.edu/getonthebus.

College digs in for new arts space

A lively crowd gathered at the ceremonial groundbreaking for the college’s new Snyder Center for the Visual Arts, a 14,000-square-foot building that will be built adjacent to existing visual arts buildings. The groundbreaking and reception on December 5 kicked off a full weekend Winter Arts Festival that included open studios, demonstrations, dance recitals, a play, and a chamber music concert.

A quarter of all Marlboro students include visual arts as part of their Plan of Concentration. The goal of the visual arts center is to make classroom and studio spaces more integrated and healthy, and to allow for a more flexible pedagogy that integrates other disciplines.

“This arts facility will provide a new creative space for all, and will welcome faculty in other disciplines to use it, hold classes, display work, and collaborate with faculty in the arts,” says President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell. “It will support the college’s mission of intellectual and artistic creativity.”

The new building will provide a more concentrated space for the ceramics program, which is now spread between two buildings, and a digital media lab, which is currently housed in the library. By its 2015 completion, the visual arts center will also include classrooms, a gallery space, student studios, a sculpture studio, and a welding area.

Also of Note

“Experience showed that serious art-making and reflection on those processes engaged students, gave teachers new tools, transferred interest from one subject to another, enlivened the school day, and kept students in school,” said President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell. Ellen gave the keynote address at a summit titled “Envisioning Arts Education in Vermont,” hosted by the Vermont Arts Council (VAC) in September. Ellen related some of her own experiences proposing and promoting arts policy in Vermont and nationally, including founding the Governor’s Institutes, which began with the arts, and directing President Clinton’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities.

“Experience showed that serious art-making and reflection on those processes engaged students, gave teachers new tools, transferred interest from one subject to another, enlivened the school day, and kept students in school,” said President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell. Ellen gave the keynote address at a summit titled “Envisioning Arts Education in Vermont,” hosted by the Vermont Arts Council (VAC) in September. Ellen related some of her own experiences proposing and promoting arts policy in Vermont and nationally, including founding the Governor’s Institutes, which began with the arts, and directing President Clinton’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities.

Junior Edward Suprenant spent the summer in Nepal studying Buddhist philosophy at the Rangjung Yeshe Institute, through a partnership between Kathmandu University and the Tulku Urgyen monastery. “The focus of my stay was to hopefully loosen any myopic conceptions of Buddhism I may have gained through my previous studies,” says Edward, who studied Zen Buddhism at a monastery in San Francisco. “I got exposed to a lot of South Asian cultural aspects I wasn’t aware of. Being in that environment and studying the things that come from that social environment was really cool.”

“In the workplace, love can exist with those who are willing to lay aside ego, let their guard down, and explore their struggles together,” says Jodi Clark ’95, former director of housing. “With extra wisdom and trust brought to a particular problem, they may also discover that a powerful resource for fueling their work is their love and care for each other.” Jodi was the subject of a blog on JustMeans.com by Julie Fahnestock MBA ’14, titled “Is Love in the Workplace the New Norm?” .

“In the workplace, love can exist with those who are willing to lay aside ego, let their guard down, and explore their struggles together,” says Jodi Clark ’95, former director of housing. “With extra wisdom and trust brought to a particular problem, they may also discover that a powerful resource for fueling their work is their love and care for each other.” Jodi was the subject of a blog on JustMeans.com by Julie Fahnestock MBA ’14, titled “Is Love in the Workplace the New Norm?” .

Photography student Julian Harris ’14 had photos published in Living on Earth, Public Radio International’s environmental news magazine, in October. His striking images of traditional tanneries in Morocco were the result of a research project he did there during a program through the School for International Training (SIT), in collaboration with a fellow SIT student. The article focuses on the toxic chemicals used in traditional tanneries, which can result in serious health and environmental problems.