Fall 2015

Editor’s Note

“Over and over I find that endings and beginnings are not as clear-cut as I had imagined, that they necessitate one another, and just…keep happening,” writes Maya Rohr. The eloquent and memorable student speaker at last May’s undergraduate commencement, Maya contributed a suitably apt feature about transformation to this issue of Potash Hill.

“Over and over I find that endings and beginnings are not as clear-cut as I had imagined, that they necessitate one another, and just…keep happening,” writes Maya Rohr. The eloquent and memorable student speaker at last May’s undergraduate commencement, Maya contributed a suitably apt feature about transformation to this issue of Potash Hill.

Much of what keeps happening at Marlboro College, and much of the ground covered in this issue, could fall under the taxonomy and phylogeny of transformation. Perhaps the most prominent example is a welcome to Kevin Quigley, Marlboro’s ninth president, literary scholar, service-learning devotee, international development sage, ordained Buddhist monk, long-distance cyclist, and Irish national backstroke champion. Okay, that last one was a little while ago, but if anyone can embody change it is Kevin, who says his liberal arts education prepared him for “a life unexpected.”

A feature by Catherine O’Callaghan, assistant dean of academic advising, illustrates the impermanence of nature in the religious sites of Nepal visited by her class, then destroyed by earthquakes weeks later. From the profile of alumnus Randy George, who is helping frame a national discussion on workplace policies, to the photo from last May’s Town Meeting, where the Forest Ecology class proposed a forest reserve on college land, this Potash Hill is fairly brimming with transformative examples.

Most readers will recall that Potash Hill itself underwent a major transformation three issues ago. What you might not know is that the new publication received a bronze award for best writing from the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) District 1.

“The writing here was often wonderful—cerebral, poetic, thoughtful,” according to the judges. “We liked very much that the magazine let other people write—students, alumni, teachers—and there is an intimacy with the reader.” Of course, like any other transformative process, Potash Hill is always a work in progress. I welcome your comments on this issue or on the Marlboro College that keeps happening in your lives.

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the undergraduate campus was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Ella McIntosh

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

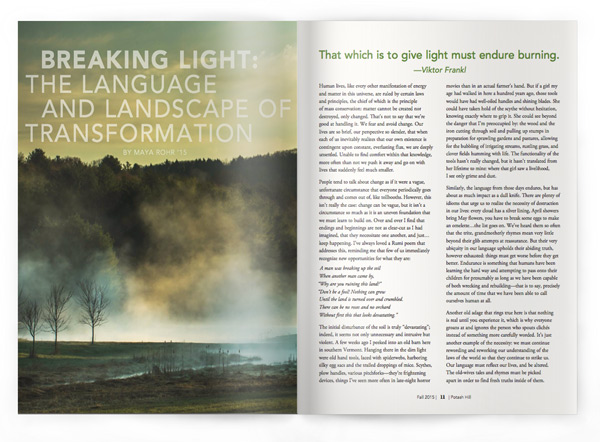

Front Cover: The Adirondack chairs in front of Mather have accommodated many an inquiring conversation over the years, with an arresting view of the changing Vermont landscape. You can see more haunting landscapes from photographer Kelly Fletcher, graduate center coordinator, and read what alumna Maya Rohr has to say about “the language and landscape of transformation.” Photo by Kelly Fletcher.

Who remembers Town Meeting? What was the biggest community issue when you were a voting member? Pets? Smoking? Lost mugs? Find out about the experience of Rainbow Stakiwicz ’16 as head selectperson.

Who remembers Town Meeting? What was the biggest community issue when you were a voting member? Pets? Smoking? Lost mugs? Find out about the experience of Rainbow Stakiwicz ’16 as head selectperson.

Marlboro College Mission Statement

The goal of the undergraduate program at Marlboro College is to teach students to think clearly and to learn independently through engagement in a structured program of liberal studies. Students are expected to develop a command of concise and correct English and to strive for academic excellence informed by intellectual and artistic creativity; they are encouraged to acquire a passion for learning, discerning judgment, and a global perspective. The college promotes independence by requiring students to participate in the planning of their own programs of study and to act responsibly within a self-governing community.

The mission of Marlboro College Graduate and Professional Studies program is to offer responsive, innovative education of the highest standard in professional studies in the topic areas of management, technology, and teaching. The educational practice of the graduate program fosters the development of critical thinking, articulate presentation, coherent concepts and arguments, superior writing skills, and the ability to apply creative, sustainable solutions to real world problems.

Up Front

Workers ankle-deep in cement pour the floor of the new Snyder Center for the Visual Arts in August. “After years of planning, we watch daily with real excitement as the Snyder Center rises toward completion,” says Tim Segar, visual arts professor. “This addition to the campus will include studios and two classrooms, one of which we will hold open for non-art classes, insuring that students from across the curriculum will enjoy this new structure and come in close contact with the work of art students.”

Clear Writing

The Right Questions

My writing has always revolved around interpersonal relationships, whether romantic or familial, with a particular eye towards why people act and react in different ways under different circumstances. All writing springs from life in some way, and what often spurs me to write fiction is trying to think my way into someone else’s decision. If I have seen someone act in a particular way and I do not understand why, their action or emotional situation often works its way into a story.

My writing has always revolved around interpersonal relationships, whether romantic or familial, with a particular eye towards why people act and react in different ways under different circumstances. All writing springs from life in some way, and what often spurs me to write fiction is trying to think my way into someone else’s decision. If I have seen someone act in a particular way and I do not understand why, their action or emotional situation often works its way into a story.

By writing a compelling character who acts in a certain way, I gain access to the why behind the actions, or at least a plausible why. Sometimes the person whose actions I do not understand is myself, and by writing I am better able to untangle a conflicted ball of emotions. Words can only go so far in explaining people, but sometimes just being able to phrase a question can lead you towards an answer.

Taken as a whole, this collection of fiction shows a variety of women who are discovering how to define themselves and their needs, both outside of and within the context of their family structures and societal expectations. None of them reach the end of their journeys, but at least they begin to figure out what questions they need to ask and what they will carry forward into the next part of their life.

I see these stories as connected to the themes of family and duty that run through Nick Flynn’s work, particularly in respect to father-child relationships, and as growing naturally out of the questions of societal and familial expectations for women which I deal with in my critical writing about Faulkner’s novels. These stories all center on women who look at themselves and their worlds and ask, “Who am I?” Their answers are not always fully formed or definitive, but they are discovering the right questions to ask.

Excerpted from “And They Will Endure: Selfhood and family in the works of Faulkner and Flynn, and an original body of fiction,” a Plan of Concentration in writing and literature by Phoebe Lumley ’15. Read one of Phoebe’s stories, “Waiting Space." Photos by Dakota Walsh ’15

Letters

Star Shutterbugs  Brattleboro photographer Bob George submitted this image of renowned photographers Angelo Lomeo and Sonja Bullaty, who for many years had a home in Belmont, Vermont, and apparently graced the slopes of Potash Hill at least once.

Brattleboro photographer Bob George submitted this image of renowned photographers Angelo Lomeo and Sonja Bullaty, who for many years had a home in Belmont, Vermont, and apparently graced the slopes of Potash Hill at least once.

“Enclosed is a photo that might want to go into the archives,” writes Bob, a longtime colleague of photography professor John Willis. “It was at the Wendell Cup Race in 1969. Are you familiar with the story of Sonja’s life?”

Sonja Bullaty, who died in 2000 at the age of 76, was born in Prague and survived four years in captivity during the war, first in Poland’s Lodz Ghetto and then in the Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen concentration camps. She escaped a death march near Dresden, then in flames, by hiding in a haystack, despite attempts by Nazi soldiers with pitchforks to find her.

“I had no camera but often saw things indelibly etched on my mind,” said Sonja, as quoted in her New York Times obituary. “Perhaps to this day I search for some of those missing images.” Sonja and Angelo made six books of their acclaimed photography, including Vermont in All Weathers.

You can see a photo from this year’s Wendell-Judd Cup. Send your photos and memories to pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

Spring Love

Loved the latest issue of Potash Hill and can’t wait to have time to sit down to read it all.

—Ede Thomas, neighbor

Congratulations on a beautiful edition of Potash Hill, celebrating Ellen and all she has done for the college. It was heartwarming to see the breadth and depth of her tenure that you explored—Thank you.

—Karen Davis, trustee

I was reminded by the latest issue of Potash Hill of many things. The front cover reminded me of the muddy weather I am happy to miss this year; Shannon Haaland’s interview of Lynette reminded me of transformative moments I had in classes and tutorials with her; Peter Mallary’s piece of course reminded me of Ellen McCulloch-Lovell and all she has done at Marlboro.

—Alexia Boggs ’13

Flourishing Future

Cary Gaunt’s article in Potash Hill (Spring 2015, page 12) asked, “How do we cultivate the ecologically enlightened citizen?” I’ve wondered the same thing. Virginia, where I live, and where Cary used to live, is a beautiful state, although lots of it has been trashed—not just with pollution, litter, and rubbish, which are plentiful, but with ugly clutter. I’ve tried to work in the other direction by helping clean up the canal in Fredericksburg and helping build and maintain trails. Some people notice, and appreciate, and participate. Yet in other ways the area is mostly in Conquest mode. People who walk or bike are mostly treated with indifference or, often, hostility. The sheriff thinks that trails near homes are a threat to public safety. In this environment, having ecologically enlightened citizens sometimes feels hopeless. Yet, as Cary pointed out, “The Flourishing stage is in a nascent state.” I see it in my children, who care moreabout our environment than, it appears, the majority of my generation. Consciousness and action, things Cary mentioned: may they flourish.

—Steve Dunham, father of John Dunham ’05

A Final Word to Birjé

We had come to measure the year by your migrations, Birje, March and November. Measure time, yes, but how to weigh an old friendship? You could remember my mother’s mother: few can now. You never forgot that slice of her homemade fruitcake she thrust into your hands for your first journey to Manchester. Such stories must await another day. Enough for now to say how much you were still alive at 80. Your third novel just completed, a tour de force portrait of Emmy Kulshesthra, who fled the destruction of her beloved Vienna to start life again in a smaller, cultured city on the other side of the globe. How were you able to bring Emmy to life so well? Was she, in another mode or scale, a surrogate self? You left an increasingly dissonant Baroda for the harmonies of Marlboro. Are the cities we know and leave, like the people we love, always passing away, to reappear, perhaps, under another name?

— John Drew, a close Cambridge friend who was visiting faculty emeritus Jaysinh Birjepatil in India when he died (Potash Hill, Spring 2015, page 46).

Mother Marlboro

My first day at Marlboro I met Ellen, also known as Mother Marlboro. After a long talk about my journey, she whispered in my ear, “You’re going to do well here, Seth.” I’ll never forget that moment and how incredibly powerful that was. My fear was swept away, and someone I didn’t even know believed in me. That, when it happens in the world, is a beautiful thing. Over the next four years Ellen would become a source of inspiration for me. She would commit herself to the school’s dance performances, plays, musicals, film festivals, newspaper articles, broomball tournaments, Town Meetings, admissions tours, and anything else going on in the village. She gave an incredible amount of herself to us all, and we are forever grateful.

—Seth Bowman ’08

For all of us at Marlboro Music School, our collaboration with Ellen McCulloch-Lovell over the last 11 years has been a joy. We have had a mutual appreciation for the unique nature of each of our institutions. Both the college and the music school have an original approach to learning, nurturing the individual to explore deeply and find their voice and that of the subject they are studying. Ellen not only appreciates the arts—we first got to know her when she headed the Vermont Arts Council—but she understands its vital importance in education and in society. We have the greatest admiration for all that she accomplished at the college and the spirit in which we worked together to create mutually beneficial projects. We will miss her and her warm smile, but hope to see her at our concerts in future summers.

For all of us at Marlboro Music School, our collaboration with Ellen McCulloch-Lovell over the last 11 years has been a joy. We have had a mutual appreciation for the unique nature of each of our institutions. Both the college and the music school have an original approach to learning, nurturing the individual to explore deeply and find their voice and that of the subject they are studying. Ellen not only appreciates the arts—we first got to know her when she headed the Vermont Arts Council—but she understands its vital importance in education and in society. We have the greatest admiration for all that she accomplished at the college and the spirit in which we worked together to create mutually beneficial projects. We will miss her and her warm smile, but hope to see her at our concerts in future summers.

—Frank Salomon, Marlboro Music School & Festival

Breaking Light: The Language and Landscape of Transformation

By Maya Rohr ‘15

That which is to give light must endure burning. —Viktor Frankl

Human lives, like every other manifestation of energy and matter in this universe, are ruled by certain laws and principles, the chief of which is the principle of mass conservation: matter cannot be created nor destroyed, only changed. That’s not to say that we’re good at handling it. We fear and avoid change. Our lives are so brief, our perspective so slender, that when each of us inevitably realizes that our own existence is contingent upon constant, everlasting flux, we are deeply unsettled. Unable to find comfort within that knowledge, more often than not we push it away and go on with lives that suddenly feel much smaller.

Human lives, like every other manifestation of energy and matter in this universe, are ruled by certain laws and principles, the chief of which is the principle of mass conservation: matter cannot be created nor destroyed, only changed. That’s not to say that we’re good at handling it. We fear and avoid change. Our lives are so brief, our perspective so slender, that when each of us inevitably realizes that our own existence is contingent upon constant, everlasting flux, we are deeply unsettled. Unable to find comfort within that knowledge, more often than not we push it away and go on with lives that suddenly feel much smaller.

People tend to talk about change as if it were a vague, unfortunate circumstance that everyone periodically goes through and comes out of, like tollbooths. However, this isn’t really the case: change can be vague, but it isn’t a circumstance so much as it is an uneven foundation that we must learn to build on. Over and over I find that endings and beginnings are not as clear-cut as I had imagined, that they necessitate one another, and just… keep happening. I’ve always loved a Rumi poem that addresses this, reminding me that few of us immediately recognize new opportunities for what they are:

A man was breaking up the soil

When another man came by,

“Why are you ruining this land?”

“Don’t be a fool! Nothing can grow

Until the land is turned over and crumbled.

There can be no roses and no orchard

Without first this that looks devastating.”

The initial disturbance of the soil is truly “devastating”; indeed, it seems not only unnecessary and intrusive but violent. A few weeks ago I peeked into an old barn here in southern Vermont. Hanging there in the dim light were old hand tools, laced with spiderwebs, harboring silky egg sacs and the trailed droppings of mice. Scythes, plow handles, various pitchforks—they’re frightening devices, things I’ve seen more often in late-night horror movies than in an actual farmer’s hand. But if a girl my age had walked in here a hundred years ago, those tools would have had well-oiled handles and shining blades. She could have taken hold of the scythe without hesitation, knowing exactly where to grip it. She could see beyond the danger that I’m preoccupied by: the wood and the iron cutting through soil and pulling up stumps in preparation for sprawling gardens and pastures, allowing for the bubbling of irrigating streams, rustling grass, and clover fields humming with life. The functionality of the tools hasn’t really changed, but it hasn’t translated from her lifetime to mine: where that girl saw a livelihood, I see only grime and dust.

The initial disturbance of the soil is truly “devastating”; indeed, it seems not only unnecessary and intrusive but violent. A few weeks ago I peeked into an old barn here in southern Vermont. Hanging there in the dim light were old hand tools, laced with spiderwebs, harboring silky egg sacs and the trailed droppings of mice. Scythes, plow handles, various pitchforks—they’re frightening devices, things I’ve seen more often in late-night horror movies than in an actual farmer’s hand. But if a girl my age had walked in here a hundred years ago, those tools would have had well-oiled handles and shining blades. She could have taken hold of the scythe without hesitation, knowing exactly where to grip it. She could see beyond the danger that I’m preoccupied by: the wood and the iron cutting through soil and pulling up stumps in preparation for sprawling gardens and pastures, allowing for the bubbling of irrigating streams, rustling grass, and clover fields humming with life. The functionality of the tools hasn’t really changed, but it hasn’t translated from her lifetime to mine: where that girl saw a livelihood, I see only grime and dust.

Similarly, the language from those days endures, but has about as much impact as a dull knife. There are plenty of idioms that urge us to realize the necessity of destruction in our lives: every cloud has a silver lining, April showers bring May flowers, you have to break some eggs to make an omelette…the list goes on. We’ve heard them so often that the trite, grandmotherly rhymes mean very little beyond their glib attempts at reassurance. But their very ubiquity in our language upholds their abiding truth, however exhausted: things must get worse before they get better. Endurance is something that humans have been learning the hard way and attempting to pass onto their children for presumably as long as we have been capable of both wrecking and rebuilding—that is to say, precisely the amount of time that we have been able to call ourselves human at all.

Another old adage that rings true here is that nothing is real until you experience it, which is why everyone groans at and ignores the person who spouts clichés instead of something more carefully worded. It’s just another example of the necessity: we must continue rewording and reworking our understanding of the laws of the world so that they continue to strike us. Our language must reflect our lives, and be altered. The old-wives tales and rhymes must be picked apart in order to find fresh truths inside of them.

Another old adage that rings true here is that nothing is real until you experience it, which is why everyone groans at and ignores the person who spouts clichés instead of something more carefully worded. It’s just another example of the necessity: we must continue rewording and reworking our understanding of the laws of the world so that they continue to strike us. Our language must reflect our lives, and be altered. The old-wives tales and rhymes must be picked apart in order to find fresh truths inside of them.

When I was 15, I began to suffer from debilitating panic attacks. My mother comforted me one night as I trembled and sobbed at the kitchen counter. Stroking my hair, she murmured to me, “We’re cut from the same cloth.” I was not reassured. I became angry, and cried out and pushed her hands away. I thought, How could something so meaningless help me? Even worse, taken literally it meant that my mother was just as weak and vulnerable as I was—that she was just as helpless in the face of my terror. I shut her out, and the panic continued to shudder through me.

Years later, after therapists, drugs, and support groups had begun to ease the paranoia, I began to grasp the intention behind my mother’s attempt at comfort. She was right; we were cut from the same cloth, in a way. As we sat together in the dark kitchen, with cups of tea she had made for us untouched and no longer steaming, she had been trying to tell me that my fear had been hers once. If only I had been able to look beyond my own terror that night and see my mother the way she saw herself: a scarred woman who had fought off the demons of her childhood and refused to succumb. If only I could have looked at her and seen not my weakness, but her strength.

So here I am, still. Here we are. All of our hopes, our fears, our annoyances and apologies laid out before us. We change, this we know. The scythe blade is forged, tempered, polished, used, abandoned, rusted, and polished once again. I am no different. In winter I trudge up the same hills I rolled down in the summer. I cut my hair and it grows long, and I call my mother to tell her I miss her. The glaciers that formed these fields have receded and cracked away from themselves, leaving gemstones and crushed ravines in their wake. Let us repeat ourselves and be ignored, just as the world repeats its miraculous laws unnoticed. We will keep on spouting clichés, old as they are. Our children will not understand, until they do.

So here I am, still. Here we are. All of our hopes, our fears, our annoyances and apologies laid out before us. We change, this we know. The scythe blade is forged, tempered, polished, used, abandoned, rusted, and polished once again. I am no different. In winter I trudge up the same hills I rolled down in the summer. I cut my hair and it grows long, and I call my mother to tell her I miss her. The glaciers that formed these fields have receded and cracked away from themselves, leaving gemstones and crushed ravines in their wake. Let us repeat ourselves and be ignored, just as the world repeats its miraculous laws unnoticed. We will keep on spouting clichés, old as they are. Our children will not understand, until they do.

Maya Rohr graduated in May with a Plan of Concentration in ceramics & American literature, specifically a meditation on domesticity and loss in the work of Emily Dickinson and Marilynne Robinson. She was elected by her peers as the senior speaker at their commencement, and you can find her moving comments about Marlboro and the importance of honest discourse here. Photos by Kelly Fletcher

Making Sense of Loss“Place is integral to the art I make, but it is my relationship to place and all that is entangled in it that makes my work,” says Liza Mitrofanova ’15. The biology portion of Liza’s Plan of Concentration focused on the intricate relationship between plants, soil bacteria called rhizobia, and mycorrhizal fungi, including a pilot field study on the college farm. But her art is all about the slow, inexorable process of loss—loss of her childhood memories from growing up in Russia, some of her native language, even parts of her family. Liza’s ceramics installation included giant, melting blocks of ice harvested from the fire pond. “Handing over this work to processes outside of my control is an attempt to recreate the experience of loss and to make sense of it somehow. It embraces impermanence and embodies the notion that loss is change and from change comes growth.”

When the Earth Speaks

By Catherine O’Callahan

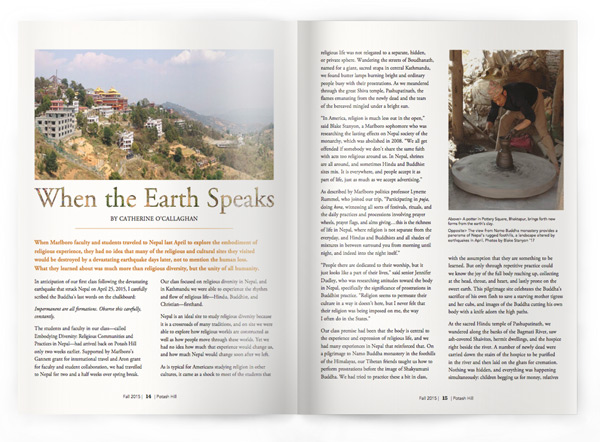

When Marlboro faculty and students traveled to Nepal last April to explore the embodiment of religious experience, they had no idea that many of the religious and cultural sites they visited would be destroyed by a devastating earthquake days later, not to mention the human loss. What they learned about was much more than religious diversity, but the unity of all humanity.

In anticipation of our first class following the devastating earthquake that struck Nepal on April 25, 2015, I carefully scribed the Buddha’s last words on the chalkboard:

In anticipation of our first class following the devastating earthquake that struck Nepal on April 25, 2015, I carefully scribed the Buddha’s last words on the chalkboard:

Impermanent are all formations. Observe this carefully, constantly.

The students and faculty in our class—called Embodying Diversity: Religious Communities and Practices in Nepal—had arrived back on Potash Hill only two weeks earlier. Supported by Marlboro’s Gannett grant for international travel and Aron grant for faculty and student collaboration, we had travelled to Nepal for two and a half weeks over spring break. Our class focused on religious diversity in Nepal, and in Kathmandu we were able to experience the rhythm and flow of religious life—Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian—firsthand.

Nepal is an ideal site to study religious diversity because it is a crossroads of many traditions, and on site we were able to explore how religious worlds are constructed as well as how people move through these worlds. Yet we had no idea how much that experience would change us, and how much Nepal would change soon after we left.

As is typical for Americans studying religion in other cultures, it came as a shock to most of the students that religious life was not relegated to a separate, hidden, or private sphere. Wandering the streets of Boudhanath, named for a giant, sacred stupa in central Kathmandu, we found butter lamps burning bright and ordinary people busy with their prostrations. As we meandered through the great Shiva temple, Pashupatinath, the flames emanating from the newly dead and the tears of the bereaved mingled under a bright sun.

“In America, religion is much less out in the open,” said Blake Stanyon, a Marlboro sophomore who was researching the lasting effects on Nepal society of the monarchy, which was abolished in 2008. “We all get offended if somebody we don’t share the same faith with acts too religious around us. In Nepal, shrines are all around, and sometimes Hindu and Buddhist sites mix. It is everywhere, and people accept it as part of life, just as much as we accept advertising.”

As described by Marlboro politics professor Lynette Rummel, who joined our trip, “Participating in puja, doing kora, witnessing all sorts of festivals, rituals, and the daily practices and processions involving prayer wheels, prayer flags, and alms giving…this is the richness of life in Nepal, where religion is not separate from the everyday, and Hindus and Buddhists and all shades of mixtures in between surround you from morning until night, and indeed into the night itself.”

As described by Marlboro politics professor Lynette Rummel, who joined our trip, “Participating in puja, doing kora, witnessing all sorts of festivals, rituals, and the daily practices and processions involving prayer wheels, prayer flags, and alms giving…this is the richness of life in Nepal, where religion is not separate from the everyday, and Hindus and Buddhists and all shades of mixtures in between surround you from morning until night, and indeed into the night itself.”

“People there are dedicated to their worship, but it just looks like a part of their lives,” said senior Jennifer Dudley, who was researching attitudes toward the body in Nepal, specifically the significance of prostrations in Buddhist practice. “Religion seems to permeate their culture in a way it doesn’t here, but I never felt that their religion was being imposed on me, the way I often do in the States.”

Our class premise had been that the body is central to the experience and expression of religious life, and we had many experiences in Nepal that reinforced that. On a pilgrimage to Namo Buddha monastery in the foothills of the Himalayas, our Tibetan friends taught us how to perform prostrations before the image of Shakyamuni Buddha. We had tried to practice these a bit in class, with the assumption that they are something to be learned. But only through repetitive practice could we know the joy of the full body reaching up, collecting at the head, throat, and heart, and lastly prone on the sweet earth. This pilgrimage site celebrates the Buddha’s sacrifice of his own flesh to save a starving mother tigress and her cubs, and images of the Buddha cutting his own body with a knife adorn the high paths.

At the sacred Hindu temple of Pashupatinath, we wandered along the banks of the Bagmati River, saw ash-covered Shaivites, hermit dwellings, and the hospice right beside the river. A number of newly dead were carried down the stairs of the hospice to be purified in the river and then laid on the ghats for cremation. Nothing was hidden, and everything was happening simultaneously: children begging us for money, relatives weeping for their dead, women doing laundry, children fishing, and music wafting through the smoky places. High above the river we were able to see rows of Shiva lingams, simple representations of the Hindu deity that are among the oldest religious symbols, reverberating in a line that seemed never to end.

When we visited Bhaktapur, an ancient Newar city known as Place of Devotees, with its labyrinthine alleys and tremendous South Indian temple architecture, we marveled at images from the Kama Sutra exquisitely carved into the Krishna temple. We were blessed with tikka head jewelry in the house of the Kumari, one of Nepal’s living goddesses. Around corners we saw women gathered by wells, bringing up water from the deep, and our guide pointed out a group of wailing women, saying that someone had just died at home. The potter’s square, full now with piggy banks for the tourist trade, was hot in the sun. Women bent over pots, setting them down ever so carefully. The clay—thought to be auspicious—emerges from the earth.

Exploring another strand in the complex weave of religious practice in Nepal, Marlboro junior Jonah Nonomaque collaborated with Lynette Rummel on research regarding conversion to Protestantism. “Very little research has been done on the growth of Christianity in Nepal, so I was eager to help fill this void while applying, testing, and enriching my own theoretical insights,” said Jonah, who has also studied Protestant conversion in upland Southeast Asia. “As an aspiring anthropologist, I found the opportunity to engage in fieldwork highly rewarding and challenging.”

Jonah and Lynette attended an evangelical church service that seemed to have no discernible beginning or end, and Lynette was even summoned to the pulpit by the pastor to give a short speech (including a “shout-out” to Marlboro College). The video presentation they made based on their experiences displayed worshippers slain in the spirit, a laying on of hands, a shaking body, and finally a worshipper in repose. The extreme physicality of the expression did not seem out of place among all we had seen so far in Kathmandu.

We ascended the steps to the great Stupa of Svayambhu and explored a world where Buddhist and Hindu expression coexist and mutually celebrate each other. At the threshold of the shrine, with our students huddled round, Buddhist studies scholar Hubert Decleer retold the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment and how the very earth rose as witness. The Buddha’s classic pose— fingers touching the ground—evoked the earth goddess herself. As we entered the cavernous shrine to the earth goddess Vasudhara, vermillion powder flashing red on the well-rubbed deities among the flickering butter lamps, the earth—the home, the source, the wellspring, and the grave—was never more alive to me.

We ascended the steps to the great Stupa of Svayambhu and explored a world where Buddhist and Hindu expression coexist and mutually celebrate each other. At the threshold of the shrine, with our students huddled round, Buddhist studies scholar Hubert Decleer retold the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment and how the very earth rose as witness. The Buddha’s classic pose— fingers touching the ground—evoked the earth goddess herself. As we entered the cavernous shrine to the earth goddess Vasudhara, vermillion powder flashing red on the well-rubbed deities among the flickering butter lamps, the earth—the home, the source, the wellspring, and the grave—was never more alive to me.

Later in April the earth rose as witness once more. When the catastrophic earthquake struck Nepal, leaving over 9,000 dead, 23,000 injured, thousands homeless, and many UNESCO world heritage sites in ruins, I recited the Buddha’s last words to my class: “Impermanent are all formations. Observe this carefully, constantly.” I told the students that it was a practice of mine to memorize important texts, in the event that the paper, the stone, even the temples they are inscribed upon disappear. As, indeed, they will.

We shared our feelings of shock and helplessness in the wake of the disaster, the deadliest earthquake to hit Nepal on record. New friends did not turn up on Facebook; familiar sacred places had fallen; a country, whose weak infrastructure and poverty had been so evident to us, was now in crisis. I reminded the class of our first readings of the semester: the Bhagavad Gita. Many had wrestled with the text, the apparent fatalism of Krishna’s instructions to Arjuna, and Arjuna’s confusion.

I am weighed down by pity, Krishna; my mind is utterly confused. Tell me where my duty lies, which path I should take.

I am weighed down by pity, Krishna; my mind is utterly confused. Tell me where my duty lies, which path I should take.

I ventured to suggest that Arjuna’s quandary was now ours: what is the correct response to such a vision, to such a horrific event, when the earth speaks with such violence? When Krishna reveals the universal form, Arjuna, although overwhelmed, resolves to perform his duty.

Arjuna saw the whole

Universe

Enfolded, with its countless

Billions

Of life-forms, gathered

Together

In the body of the God of gods.

Our students rallied, and held two auctions to raise funds to support earthquake relief efforts. Students donated items they had bought in Kathmandu and wonderful works from Marlboro’s many artists. We gave to the Earthquake Relief Fund at Shechen Monastery, because we had stayed in their guesthouse; we also contributed to Himalayan Roots to Fruits, who were our Tibetan “buddies,” as well as SEBS North America Nepal. Altogether the Marlboro community— students, alumni, staff, faculty, and trustees—mobilized to raise over $10,000 to send to Nepal.

“The money we raised is insignificant in the grand picture of things, but it is not insignificant: for we have been touched, and now we care deeply and personally,” said Lynette. “Events in Nepal are no longer just a story in the news. They are part of our lives. And while our efforts pale in comparison to the task of the rebuilding that lies ahead, what we have learned has made us more compassionate, more empathetic, more human.”

Our investigation of religious diversity, and our trip to Nepal in particular, taught us that no matter how far away and exotic other cultures are, we are all part of the same earth. And when the earth speaks, we will ask with Arjuna:

Teach me the way of worship

What it is, here, in the body.

Catherine O’Callaghan is assistant dean of academic advising at Marlboro College. She has a master of theological studies (MTS) in biblical studies from the Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a BA in English and theology from Fordham University.

Embodying Unchurched Spirituality Far from the crowded streets of Kathmandu, but with a similar purpose, Alex Bobella ’15 explored the importance of movement in spiritual belief for his Plan in religion and dance. He was specifically interested in religious beliefs existing outside of organized religion, loosely categorized as “unchurched” spirituality, and the work of contemporary artist Deborah Hay, whose choreography features a “focused inquiry into bodiliness.” “The body, according to Hay, is capable of forms and understandings that the conscious mind is not,” says Alex, who presented a Plan performance titled “A Catalogue of Non-Definitive Acts.” “Ever-present and constantly interpreting amorphous reality, while the analytical mind is caught in worry, the body surpasses the cognitive mind in contextualizing the self within the world. The body is a vessel for spiritual experience that celebrates a fundamental human quality—movement—and can be used in service of creating peak, almost transcendent, experiences.”

Far from the crowded streets of Kathmandu, but with a similar purpose, Alex Bobella ’15 explored the importance of movement in spiritual belief for his Plan in religion and dance. He was specifically interested in religious beliefs existing outside of organized religion, loosely categorized as “unchurched” spirituality, and the work of contemporary artist Deborah Hay, whose choreography features a “focused inquiry into bodiliness.” “The body, according to Hay, is capable of forms and understandings that the conscious mind is not,” says Alex, who presented a Plan performance titled “A Catalogue of Non-Definitive Acts.” “Ever-present and constantly interpreting amorphous reality, while the analytical mind is caught in worry, the body surpasses the cognitive mind in contextualizing the self within the world. The body is a vessel for spiritual experience that celebrates a fundamental human quality—movement—and can be used in service of creating peak, almost transcendent, experiences.”

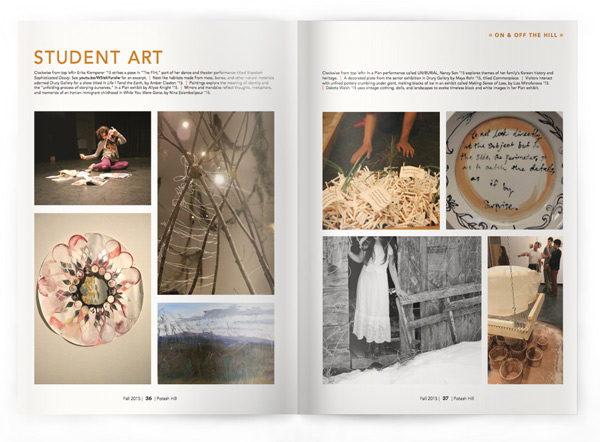

True Colors

By Nancy Son ’15

This past year, seniors Nina Eslambolipour, Alysse Knight, and I, along with other people of color, wrestled with our bicultural experiences through artistic efforts in our Plan of Concentration. I see this work as being part of a larger effort for Marlboro’s minority community to turn up the volume on their voices, to fill a dangerous void that exists in multiracial understanding in this college and in this country.

At Town Meeting last April, a minority student resource group newly initiated by several students of color introduced language to legitimize its role in the Marlboro College community. The founding members of the group, called Living in Color, had already organized a poetry reading, a series of well-attended and thought-provoking meetings open to the student body, and trips off the hill. Now here they were, in front of the larger Marlboro community, defending the right of students of color to meet, if so desired, without the presence of people who do not identify as people of color.

The worried questions were raised: “Who gets to decide who is a person of color?” And a concern that is familiar to me, even one that I have shared before: “Wouldn’t such exclusivity be destructive to the order and harmony of the community?” A fear of division and difference was palpable in the room.

I do not want differences in experience to divide people. But the extremely helpful thing I have realized, in exploring my own multicultural experience in Vermont, is that differences do divide people. The real danger is in ignoring these differences and the power that they carry, because we are afraid of the possibility of division; we become so afraid that we lose faith in what it is that we share.

As I found in the difficult but life-changing work I did in my exploration of my own Korean-American identity this past year, fear does not allow for spaces where an articulation of rich experience can happen. The Marlboro community should not only welcome public articulation of the racial minority’s experience but also provide what is necessary for articulation like this to occur—practice and space, without the constant threat of misunderstanding or questioning—just as we do for the diversity of educational experiences found on Potash Hill.

Nancy Son graduated in May with a Plan of Concentration in politics focusing on how performance can strengthen individual agency and community. You can see more of her art installation, and the work of Nina and Alysse, on page 35.

Living in Color is now established, and readers can expect more to come from this important group. If alumni of color are interested in serving as a community resource for Living in Color, please contact Alumni Director Kathy Waters.

On and Off the Hill

Inaugurating a new president, welcoming a new theater professor, launching a new semester-long intensive, celebrating students who compose operas, compete in ski jumps, and check out more books from the library than any mortal could read. There's so many reasons to explore what's going on at Marlboro College.

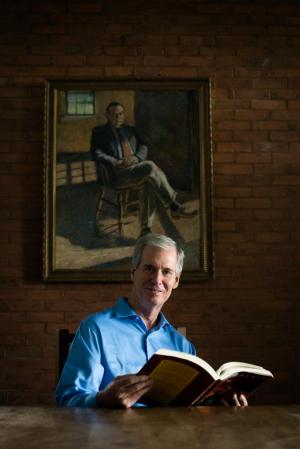

A Culture of Gratitude: Kevin Quigley takes the helm

Marlboro College welcomed Kevin Quigley as its ninth president in July, followed by a full weekend of inauguration events in September (see page 20). Kevin brings to Marlboro a wealth of experience in international arenas, nonprofit organizations, and academia that stands to make a marked difference for the college—indeed, making a difference seems to be what he does best.

“My big goal is to strengthen connections between the college and the community, and between the community and the college,” says Kevin, who was Peace Corps country director in Thailand before coming to Marlboro. “How do you do that? You need some mechanisms, and there are several possibilities, but I think one viable mechanism is through service.”

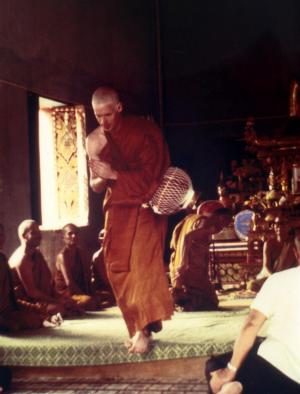

Kevin’s experience with service stretches back to his own college years at Swarthmore, when he spent a semester teaching at an underserved school in West Philadelphia and a summer teaching in Kenya through the East Africa Yearly Meeting of Friends. After receiving his master’s at the National University of Ireland, where he wrote his thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses and rubbed elbows with notable literary figures, he served with the Peace Corps in Thailand.

“I had two particular interests, Irish literature and Theravada Buddhism,” he says. “I had an opportunity to go deep into literature through my work on Ulysses, and to publish my own poetry in various magazines while I was in Dublin. Peace Corps was really the way for me to dive into Thai culture, which is 95 percent Theravada Buddhist.”

It was a life-changing experience for Kevin, as Peace Corps so often is. He arrived in Thailand soon after the U.S. had pulled out of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but there was still fighting in that part of the world. He taught in a remote village, 15 kilometers from Laos, in a border province where there was an ongoing insurgency.

It was a life-changing experience for Kevin, as Peace Corps so often is. He arrived in Thailand soon after the U.S. had pulled out of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but there was still fighting in that part of the world. He taught in a remote village, 15 kilometers from Laos, in a border province where there was an ongoing insurgency.

Testament to Kevin’s courage and diplomatic skills, he persuaded the Peace Corps and the Thai government that for his individual project he should get ordained as a Buddhist monk. This involved trekking to the provincial capital, 92 kilometers away through the mountains on dirt roads, for one weekend each month, monsoon or shine, to learn the rules, rites, prayers, and chants of the tradition. He then had to pass an examination in Pali, the language of the Theravada school tracing back to the Buddha’s time.

“A lot of language is about culture and ways of thinking,” says Kevin. “Having gotten pretty good at Thai, and then having this experience that is a major rite of passage in that society, it changed my relationships with Thais. As in many places, as an outsider you are tested as to who you are, and how empathetic you are. My understanding and respect for the Thai people were a given once I’d been ordained.”

Kevin’s service in Thailand altered how he thought of himself relative to the rest of humanity: he developed an abiding sense of compassion and, as they say in the Peace Corps, became at home in the world. It also gave him important skills he would use throughout his career and, perhaps most importantly, steeled his resolve to learn what was needed to make a difference.

“I saw what a raw deal my students and their parents got, and how they didn’t have access to resources. To someone who had done nothing but the humanities in college, it was an eye-opening experience—but like students here at Marlboro, I had also learned how to learn, and my time in Thailand motivated me to learn about economics and politics. I wanted to make things a little better for people like the villagers I worked with.”

Kevin had an internship with the United Nations Development Program in Trinidad and Tobago, and earned his Master of International Affairs in economic and political development from Columbia University. Then, in Washington D.C., he oversaw foreign assistance agencies in President Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget and served as legislative director to U.S. Senator John Heinz, focusing on international financial and education issues. It was “a fabulous education inhow Washington and the world worked,” says Kevin, but the real watershed moment came in 1989, when he started as director of public policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Kevin had an internship with the United Nations Development Program in Trinidad and Tobago, and earned his Master of International Affairs in economic and political development from Columbia University. Then, in Washington D.C., he oversaw foreign assistance agencies in President Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget and served as legislative director to U.S. Senator John Heinz, focusing on international financial and education issues. It was “a fabulous education inhow Washington and the world worked,” says Kevin, but the real watershed moment came in 1989, when he started as director of public policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“It’s really rare in life that you can think of a problem or issue, and your first concern doesn’t have to be about resources,” says Kevin. “Although I hadn’t even heard of it before, at that time Pew was the second-largest foundation in the U.S., based on money out the door.” It was the end of the Soviet Union, the establishment of newly independent nations and economies in Central Europe, and all of the new leaders wanted access to Western ideas and resources. “Pew commanded the resources, so I got to meet many of the individuals, like Lech Walesa, Vaclav Havel, and others, who had a major impact on that democratization process.”

Following on his work in the former Soviet republics, Kevin published his book For Democracy’s Sake: Foundations and Democracy Assistance in Central Europe (Johns Hopkins University Press), in 1997. He was interested in how political and economic changes were effected, and what role outsiders have in encouraging or promoting such changes. Unlike after World War II, when the U.S. government helped rebuild Germany and Japan, there was no such appetite for public investment after the fall of the Berlin Wall. For better or worse, private foundations were the principal catalyst for change.

“I thought, this may be a completely unique experience in recent human history, a really interesting shift in what drives global change. I wanted to provide an opportunity for people at the forefront, leaders who were all so courageous, to assess what worked and what didn’t.” Kevin helped his colleagues in Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland organize case studies in each country, providing financial and technical support, translating the results into their national language, and discussing them in public forums.

During his time at Pew, Kevin completed his doctoral degree in comparative government at Georgetown University. He wanted to conduct his own research on social change, but rather than focusing on Central Europe—where there might be conflicts of interest with his foundation work—he went back to Thailand. There he knew the language and culture, and was very familiar with the national challenges of democratization.

During his time at Pew, Kevin completed his doctoral degree in comparative government at Georgetown University. He wanted to conduct his own research on social change, but rather than focusing on Central Europe—where there might be conflicts of interest with his foundation work—he went back to Thailand. There he knew the language and culture, and was very familiar with the national challenges of democratization.

“I was particularly interested in the role that civil society organizations play in creating democratic culture. Because unless you have the values of democracy, you can create the best independent parliament, the freest press, and it’s not going to mean anything. You need a culture that respects minority rights; encourages tolerance, empathy, and patience; has accountability and transparency. So how do you create that? There are really three mechanisms: governmental, market, and civil society, that vital space between markets and the public sector.”

Kevin went on to serve as vice president for business and policy at the Asia Society and Museum, in New York, and the first executive director for the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities, based in Baltimore, Maryland. In the latter role, he pioneered work withglobal companies like Nike and The Gap, the World Bank, and various universities and community-based organizations, seeking to improve the lives of production workers. He also launched his own consulting firm, called Q&A: Quigley & Associates, working for values-based organizations on strategy, program development, and resource mobilization issues.

In 2003 Kevin came full circle, so to speak, and began nearly 10 years of service as president and CEO of the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), the global alumni organization for 200,000 former volunteers and staff. There he developed a community-based model for the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary, using social media to spark the largest engagement ever, and established the More Peace Corps Campaign, resulting in the highest appropriation in the agency’s history—a $60 million increase. He also helped secure passage of the Peace Corps Commemorative Act, signed into law by President Obama.

In 2003 Kevin came full circle, so to speak, and began nearly 10 years of service as president and CEO of the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), the global alumni organization for 200,000 former volunteers and staff. There he developed a community-based model for the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary, using social media to spark the largest engagement ever, and established the More Peace Corps Campaign, resulting in the highest appropriation in the agency’s history—a $60 million increase. He also helped secure passage of the Peace Corps Commemorative Act, signed into law by President Obama.

During his time at NPCA, Kevin designed and secured endowment funding for the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award, which recognizes volunteers’ impact on individuals they serve. The award is named for one ofKevin’s mentors, Harris Wofford, the former senator, advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., and aide to President Kennedy, who was instrumental in the formation of the Peace Corps.

“Harris is kind of the godfather of service, in our country,” says Kevin, who has found inspiration in both Wofford and Sargent Shriver, statesman, activist, and the driving force behind the founding of the Peace Corps. “Both of them were always about the future. They were pragmatic idealists: they thought big, but could deliver, could make things happen to improve the lives of people.”

Throughout his career, Kevin has maintained a deep appreciation for and engagement with academia. He was a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow at 12 liberal arts colleges from 2004 to 2012, and a faculty-practitioner graduate instructor teaching about international studies and nonprofit management from 1995 to 2011. Earlier, he was guest scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the recipient of several other international professional fellowships. He has served on the board of Swarthmore College and the American University of Afghanistan.

Throughout his career, Kevin has maintained a deep appreciation for and engagement with academia. He was a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow at 12 liberal arts colleges from 2004 to 2012, and a faculty-practitioner graduate instructor teaching about international studies and nonprofit management from 1995 to 2011. Earlier, he was guest scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the recipient of several other international professional fellowships. He has served on the board of Swarthmore College and the American University of Afghanistan.

“Liberal arts education, especially in distinctive and academically rich settings such as Marlboro College, has a unique ability to anticipate change and prepare individuals for thoughtful, purposeful, and effective engagement in the world,” says Kevin. “What can you do with a liberal arts education? As my life suggests: anything and everything—it prepares you for a life unexpected.”

“For example, I’ve never had a course in economics and politics, and most of my life has been spent in those arenas. At its best, a liberal arts education stirs a passion for lifelong learning, looking at new opportunities as they come along, and making a difference. That’s what excites me, and that’s why I’m eager to make a contribution here at Marlboro.”

Kevin recognizes that Marlboro College is in a competitive environment, that small, independent, liberal arts colleges are under siege, and that many of them offer self-directed learning in small, interdisciplinary settings. But in his short time here so far he finds that what is most distinctive about Marlboro is the profound sense of community.

“Community has always been part of the ethos, and it’s reflected in the shared governance model. When people talk about shared governance in the liberal arts context, they’re talking about staff, faculty, and board—they’re not including students. While many liberal arts colleges share the objective of helping students become citizens of the world—and I’m a believer in experiential learning— I think Marlboro has a leg up because of our practices as a community.”

“Community has always been part of the ethos, and it’s reflected in the shared governance model. When people talk about shared governance in the liberal arts context, they’re talking about staff, faculty, and board—they’re not including students. While many liberal arts colleges share the objective of helping students become citizens of the world—and I’m a believer in experiential learning— I think Marlboro has a leg up because of our practices as a community.”

Kevin is looking forward to encouraging a more robust student life, including more activities on evenings and weekends and more interactions with local and global communities, as well as with the graduate campus in Brattleboro. “I see it in our culture, I see it in our heritage, but we have to have the programs that reflect the importance of community at Marlboro,” he says.

“I think of community as having shared values and experiences and aspirations. As community members we get opportunities and privileges, but we also have some responsibilities to other people. How do I express my gratitude at being a member of community? How do I fulfill part of my obligations? Service is a great way to do it, and it’s particularly powerful in an educational context, because service helps us learn life lessons and is the gift that keeps on giving.”

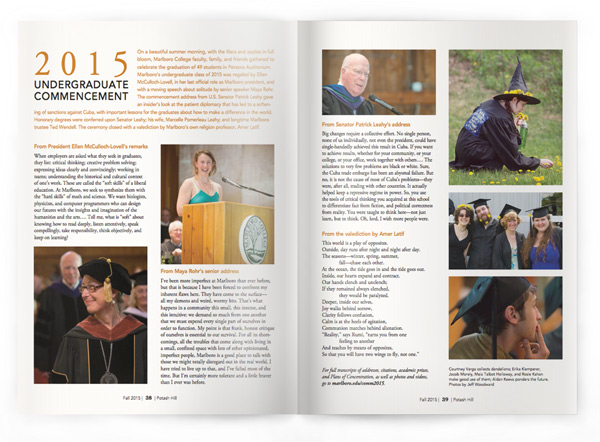

Celebrating President Kevin  Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

“Although change is never easy, Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher, teaches us that change is an entirely natural process since ‘no one steps into the same river twice,’” said Kevin in his inaugural address, titled “Marlboro Matters: The Engaged Marlboro Community of the Future.”

“The Marlboro of today is different from the Marlboro of yesterday and will be from the one of tomorrow. That river flows on, and we all must necessarily evolve with the flow. Our very engaged and amazingly supportive board has responded creatively and quickly to current challenges— again supporting how much Marlboro matters.

“Over the past few months, I have come to more deeply appreciate the fact that Marlboro matters because it continues to teach invaluable, timeless skills that have broad applicability: to think critically, to read closely, to communicate compellingly, to work in community.

“Over the past few months, I have come to more deeply appreciate the fact that Marlboro matters because it continues to teach invaluable, timeless skills that have broad applicability: to think critically, to read closely, to communicate compellingly, to work in community.

“Liberal arts, as the Greeks first posited, and as it is more recently argued by public intellectuals like Fareed Zakaria, is the best preparation for an engaged life and citizenship. As my life suggests, liberal arts graduates can do anything and everything, everywhere. There is also growing evidence from leading corporations, that they want liberal arts graduates because they work well across disciplines, problem solve, and communicate in ways that some other graduates can’t.”

For more excerpts, photos, and video from the ceremony, go to marlboro.edu/inauguration.

For more excerpts, photos, and video from the ceremony, go to marlboro.edu/inauguration.

Semester intensive reframes addiction debate

“With the recent spike in heroin overdoses in rural white America, addiction is getting a lot of attention,” says politics professor Meg Mott. “Governor Shumlin made it the sole concern of his 2014 State of the State Address. I thought it would be a good time to step back from the debate and look at how the speeches and campaigns were being framed.”

“With the recent spike in heroin overdoses in rural white America, addiction is getting a lot of attention,” says politics professor Meg Mott. “Governor Shumlin made it the sole concern of his 2014 State of the State Address. I thought it would be a good time to step back from the debate and look at how the speeches and campaigns were being framed.”

The result is Speech Matters, a new semester intensive launched by Meg this fall, which uses the humanities to delve deeply into and reframe a national issue, in this case addiction. Following the full-on, focused model pioneered by Movies from Marlboro, Speech Matters is taking one group of students through the political, economic, cultural, and racial aspects of addiction in America. In the process, each student is learning to communicate their ideas in nuanced but compelling ways and building a professional portfolio of blog posts, podcasts, op-eds, and other media content.

“The questions being posed in the current debate tend to ignore the larger structural reasons for drug use: in a town with no jobs, selling drugs is far more lucrative than panhandling,” says Meg. “In a nation with reduced social services, using drugs dulls the pain of losing custody of one’s child, not getting a callback on a job interview, or having to wait through the winter for a Section 8 voucher. By focusing on the ‘addict,’ we don’t look at the bad decisions made by policy makers, who often seem to be ruled by corporate interests.”

Meg draws inspiration for the Speech Matters program from her grandfather Archibald MacLeish, a librarian of congress, assistant secretary of state, and Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, who put as much emphasis on how things were said as on what was being said. “Archie spent enough time working for the government to know how speech could humanize or dehumanize a part of the population,” she says. “He got poet Ezra Pound out of St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital by arguing for the poet against claims that Pound was no more than a ‘crazy fascist.’”

Meg draws inspiration for the Speech Matters program from her grandfather Archibald MacLeish, a librarian of congress, assistant secretary of state, and Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, who put as much emphasis on how things were said as on what was being said. “Archie spent enough time working for the government to know how speech could humanize or dehumanize a part of the population,” she says. “He got poet Ezra Pound out of St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital by arguing for the poet against claims that Pound was no more than a ‘crazy fascist.’”

Students in Speech Matters will consider what it would look like to reframe addiction in human terms. “Instead of talking about people who use drugs as if they are deviant or different,” explains Meg, “critical theory asks us to consider who benefits from the creation of a class of ‘addicts.’” By investigating the history of drug policy and the cultural values embedded in the rhetoric of prevention, recovery, and treatment, Meg anticipates that more humanistic discussions of drug use will emerge.

“The most exciting thing for me is that we’ll be applying the skills of the humanities to an emerging political situation,” says Meg. “Right now, the 12-step programs are under scrutiny because of the Affordable Care Act, and ‘Big Pharma’ is moving in to support medication-assisted treatments. This is a very exciting time to think critically about who benefits from the existing narrative about addiction and what new, more community-based narratives might emerge.”

Jean O’Hara brings social change to theater

“I’m interested in how theater creates dialogue and new understandings,” says Jean O’Hara, who joined Brenda Foley as theater faculty last spring semester. Jean comes to Marlboro with two decades of teaching and directing experience, ten years in higher education, and a wealth of knowledge in areas of high interest to students, including political theater, environmental justice, and gender studies.

“Everything about Marlboro attracted me to Marlboro,” says Jean. “I love the fact that it has a smaller number of students, and that students have the freedom to choose what they want to study and take classes they are interested in—those are the best kind of students. At the same time, faculty can teach what they are passionate about— this is an amazing and rare opportunity as more and more universities are standardizing their curricula. I really love that Marlboro allows that freedom on both ends.”

Jean received her bachelor’s degree from Rhode Island College, her master’s from Humboldt State University, and her PhD from York University, with a dissertation that explores how two-spirit plays challenge the dominant narrative about gender and sexuality. She is also the editor of the anthology Two-Spirit Acts: Indigenous Queer Performances, and says that studying Indigenous societies has radically changed the way she views gender.

“Although I’ve been examining gender and gender politics for a long time, two-spirit scholarship radically shifted my worldview. The colonial tactics of annihilation of gender variance within Native communities was directly linked to the division of communally held land of Native nations. The communal system was replaced by individually owned property passed through the male bloodline. I believe we, both Native and non-Native people, are still living with the effects of this system, which created a binary and hierarchy between all genders.

Jean uses her work to investigate themes of racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and heterosexism, and believes in the power and efficacy that theater has to give voice to traditionally marginalized groups. Having worked with both the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, Jean credits Boal with laying the foundation for her own pedagogy, for seeing students as agents in the classroom. “We need to come from a place of equality in order to freely learn and create, versus working in hierarchical frameworks,” Jean says.

Jean is passionate about using theater as a venue for environmental justice, and for creating and maintaining local food sources. She co-edited and co-directed the play Salmon is Everything, which encouraged unity among farmers, ranchers, fishermen, and Native communities to all work for a cleaner river and healthy salmon runs in California and Oregon’s Klamath Basin.

“Having helped co-create Salmon is Everything, and bringing it out to reservations, really showed me the power of storytelling on another level,” says Jean. “To have non-Native community members and Native people from three different nations all working together to help keep the river healthy for everyone was really powerful. The play actually helped with that coalition— instead of all fighting for water, farmers and ranchers and fishermen and Native people were all looking at the bigger issue, which were the dams that stopped the flow of water. I’m proud that the play helped lead to legislation for those dams to come down.”

Last spring, Jean incorporated the community greenhouse into her class called Eco-Drama: Staging the Environment and Community, which culminated with harvesting their produce and making a meal combined with produce from other local farmers. She’s interested in local food and the slow food movement as a sustainable alternative to the present “megafood industry,” which is harmful to the land, animals, and workers.

This fall semester, Jean is offering two one-credit courses called Theater in the Wilds, which combine theater exercises with an outdoor adventure—a rafting trip and a backpacking trip, respectively. She is also collaborating with Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson to present Teatreras y Directoras, a course about Latin women who make theater and films exploring identity, family, citizenship, and class, among other topics.

“I see theater and storytelling as an important way to connect, build community, and create a much-neededto be heard,” she says. “I’m excited about co-creating with Brenda a really engaging theater program in the next few years. We are thrilled about our connection with the Vermont Performance Lab, and looking forward to incorporating Marlboro College theater more into the community.”

For Marlboro students interested in theater, Jean suggests exploring every aspect of the discipline, from playwriting to design, from acting to directing. “I think it’s really important for every theater artist to read and attend plays to expand how they view and present stories. She also suggests that students take risks in classes and on the stage. “Theater is such a gift of opening up your world and creating deep intimacy—it will change you in ways you never imagined.”

Also of Note

At the final Town Meeting last spring, the library announced that the annual “Check Me Out” Award, for checking out the most books in an academic year, went to Emily Tatro ’16. Emily smoked the opposition by taking out a stunning 103 books in the pursuit of her intellectual interests. While Marlboro College students take out an average of 52 books a year from the library, the national average for college students is 12.

At the final Town Meeting last spring, the library announced that the annual “Check Me Out” Award, for checking out the most books in an academic year, went to Emily Tatro ’16. Emily smoked the opposition by taking out a stunning 103 books in the pursuit of her intellectual interests. While Marlboro College students take out an average of 52 books a year from the library, the national average for college students is 12.

Louisa Jenness ’15 passed the highest level of the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi, a Chinese proficiency test for non-native Chinese speakers and the only international standardized exam recognized by the Republic of China. She passed level VI, which means she has a vocabulary of more than 5,000 characters and can effectively express herself both orally and on paper.

In February, sophomore Chris Lamb competed at the Harris Hill ski jumping competition in Brattleboro. Chris first competed at Harris Hill at the age of 11 and still holds the record for the longest jump there, at 102 meters, set in 2010. “It’s like learning how to ride a bike—you don’t forget,” said Chris. During the competition the announcers nicknamed him “the Professor,” because they saw him reading Immanuel Kant.

Benchmarks for a Better Vermont, a program of Marlboro’s Center for New Leadership (CNL), sponsored a training geared specifically for results-based accountability (RBA) trainers in April. Results expert Deitre Epps led the program, which was attended by a diverse group with deep experience in Vermont, and from as far away as Florida and Australia.

Theresa Chockbengboun ’15 (pictured right) was awarded a Fulbright U.S. Student Program grant to teach English at a university in Laos, while pursuing research opportunities in public health. “I’m excited to spend an entire year in another country and to learn about their culture and unique challenges in facing the future,” said Theresa. She did her Plan on public health in Southeast Asia, including an investigation of water quality and the use of “biosand” filters in Cambodian villages.

In April, seniors Edward Suprenant and Christian Lampart attended the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium at Green Mountain College. Edward presented a paper about the tendency toward essentialism in historical studies of Buddhist traditions. “The idea that there is an essential practice or idea throughout history that is Buddhist is completely against the practices and ideas of Buddhism,” says Edward. Meanwhile, Christian presented a paper on Orthodox Christianity.

With support from a summer internship grant, senior Felix Jarrar spent his summer workshopping a new opera, The Fall of the House of Usher. Based on Edgar Allan’ Poe’s story by the same name, Felix’s opera tells the famed gothic tale from the perspective of Lady Madeline. The main project for his Plan of Concentration, the opera will be premiered next March at Marlboro and at the DiMenna Center in New York City. Learn more.

Events

1 During Earth Week, politics professor Meg Mott brought in a tribe of baby goats for a little much-deserved goat therapy, here enjoyed by Sarah Palacios ’17. 2 Acclaimed geophilosopher David Abram (pictured right, with philosophy professor William Edelglass and Aidan Keeva ’15) gave an engaging talk titled “Between the Body and the Breathing Earth.” 3 Local artist Betsy MacArthur presented a show of her private journals and other work called Turning the Pages. 4 A screening of Peter and John, the new film by professor Jay Craven, created as part of the Movies from Marlboro intensive, took place at the Latchis Theatre in April. 5 In February, the annual Wendell-Judd Cup hosted a good crowd including young Will Koch, the cup winner this year and son of Olympic medalist and Wendell-Judd record holder Bill Koch. 6 The Bamidele Dancers and Drummers gave a concert in Ragle Hall in February, presenting music and dance from Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean. 7 In April, Connecticut College professor Suffia Uddin presented a talk called “Interrogating Our Own Questions about Muslim Women, Islam, and the Veil."

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

Photography professor John Willis was visited by junior Shannon Haaland to talk about teaching, his latest work, and how new students help keep his own vision fresh. You can read the whole interview.

Shannon Haaland: What do you like most about working with Marlboro students?

John Willis: Marlboro students designing their own Plans of Concentration bring their interests to the table, so I am always learning about different relationships and different topics and different contemporary issues. It keeps it really exciting. I love the time of year when I get so busy I don’t sleep regular nights, like Plan students.

SH: So, students still surprise you with their work?

JW: Honestly, even intro class students surprise me with their work, and intro is where you are trying to teach promising new students the same fundamental subject matter, every semester. It seems like it would be incredibly repetitive, but what always makes it surprising is that every student comes to it with a different mind and different abilities, and creates different images.

SH: Have students helped you in your own work process?

JW: Well, I get a lot out of working with students— the whole thing of not looking at everything the same way, and trying to experience the world differently. I learn as much about keeping an open mind from seeing how students approach things as from anywhere else.

SH: How have Marlboro students helped out with your work at Pine Ridge Reservation?

JW: Exposures—the cross-cultural youth summer program based in Brattleboro, part of the In-Sight Photography Project—was created with five Plan students. I don’t think it would have ever happened if it wasn’t for this group of students that decided they were going to do this together, without pay or credits. Whenever there is a student interest strong enough it just sort of bubbles up.

Learn more about Exposures at exposuresprogram.org. Photo by Kelly Fletcher

Focus on Faculty

“I think about how the Buddha said—something to the effect of—‘We have to live in the world as if we can make a difference, even though we will never know if we really do,’” said photography professor John Willis at a gallery talk in March. “It’s important to me to think about, ‘Can I make a difference with photography, and the way that I live my life?’” The talk was part of his exhibit of recent photography at Greenfield Community College, titled House/Home: A Work in Progress, which documents the housing conditions on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. See his gallery talk.

Cultural history professor Dana Howell has completed her work with the Open Society Foundations. The program she worked on, Regional Seminar for Excellence in Teaching, has concluded after 12 years as OSF (formerly OSI) shifts its attention elsewhere. Dana began her work with OSF in 2000, leading a visiting evaluation team to the first liberal arts college in Russia, Smolnyi College. Also of note, Dana’s book The Development of Soviet Folkloristics is being reissued by Routledge as part of a series of library editions on folklore. First published in 1992, the book is a key reference on the development of folklore study in the Soviet Union. Learn more.

“Volunteering is something I started doing at a very young age,” says MSM-MDO faculty member Julie van der Horst Jansen in a recent interview on the United Way of Windham County website. In the interview, Julie describes her work with the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program, which provides free federal and state income-tax preparation services to eligible taxpayers. “There is real caring in this community,” Julie says. “Volunteering, in general, is one of those rare opportunities where you get back what you put in. It’s satisfying and gratifying to be a volunteer: you can enjoy the work and meet new people.” See her interview.

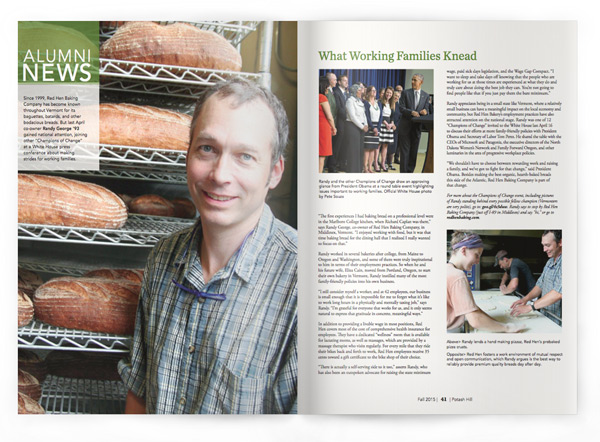

Marlboro’s social science fellow last year, anthropologist Alison Montgomery, was awarded a prestigious Science and Technology Policy Fellowship from the American Association for the Advancement of Science for this academic year. The fellowship provides the opportunity for accomplished scientists like Alison to participate in, and contribute to, the federal policy-making process while learning firsthand about the intersection of science and policy. Marlboro wishes Alison all the best.