On and Off the Hill

Inaugurating a new president, welcoming a new theater professor, launching a new semester-long intensive, celebrating students who compose operas, compete in ski jumps, and check out more books from the library than any mortal could read. There's so many reasons to explore what's going on at Marlboro College.

A Culture of Gratitude: Kevin Quigley takes the helm

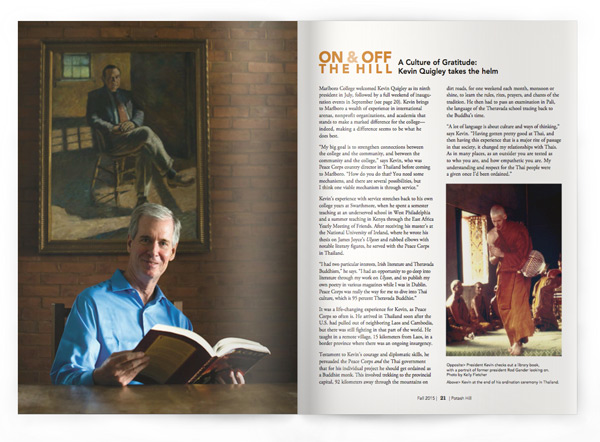

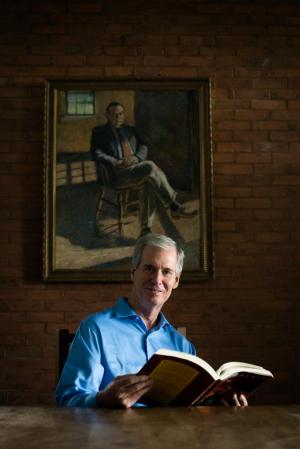

Marlboro College welcomed Kevin Quigley as its ninth president in July, followed by a full weekend of inauguration events in September (see page 20). Kevin brings to Marlboro a wealth of experience in international arenas, nonprofit organizations, and academia that stands to make a marked difference for the college—indeed, making a difference seems to be what he does best.

“My big goal is to strengthen connections between the college and the community, and between the community and the college,” says Kevin, who was Peace Corps country director in Thailand before coming to Marlboro. “How do you do that? You need some mechanisms, and there are several possibilities, but I think one viable mechanism is through service.”

Kevin’s experience with service stretches back to his own college years at Swarthmore, when he spent a semester teaching at an underserved school in West Philadelphia and a summer teaching in Kenya through the East Africa Yearly Meeting of Friends. After receiving his master’s at the National University of Ireland, where he wrote his thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses and rubbed elbows with notable literary figures, he served with the Peace Corps in Thailand.

“I had two particular interests, Irish literature and Theravada Buddhism,” he says. “I had an opportunity to go deep into literature through my work on Ulysses, and to publish my own poetry in various magazines while I was in Dublin. Peace Corps was really the way for me to dive into Thai culture, which is 95 percent Theravada Buddhist.”

It was a life-changing experience for Kevin, as Peace Corps so often is. He arrived in Thailand soon after the U.S. had pulled out of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but there was still fighting in that part of the world. He taught in a remote village, 15 kilometers from Laos, in a border province where there was an ongoing insurgency.

It was a life-changing experience for Kevin, as Peace Corps so often is. He arrived in Thailand soon after the U.S. had pulled out of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but there was still fighting in that part of the world. He taught in a remote village, 15 kilometers from Laos, in a border province where there was an ongoing insurgency.

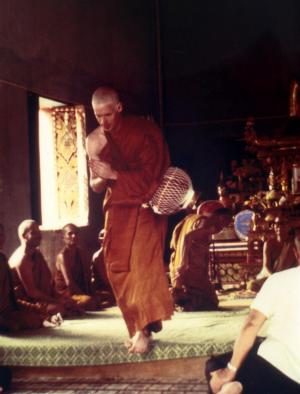

Testament to Kevin’s courage and diplomatic skills, he persuaded the Peace Corps and the Thai government that for his individual project he should get ordained as a Buddhist monk. This involved trekking to the provincial capital, 92 kilometers away through the mountains on dirt roads, for one weekend each month, monsoon or shine, to learn the rules, rites, prayers, and chants of the tradition. He then had to pass an examination in Pali, the language of the Theravada school tracing back to the Buddha’s time.

“A lot of language is about culture and ways of thinking,” says Kevin. “Having gotten pretty good at Thai, and then having this experience that is a major rite of passage in that society, it changed my relationships with Thais. As in many places, as an outsider you are tested as to who you are, and how empathetic you are. My understanding and respect for the Thai people were a given once I’d been ordained.”

Kevin’s service in Thailand altered how he thought of himself relative to the rest of humanity: he developed an abiding sense of compassion and, as they say in the Peace Corps, became at home in the world. It also gave him important skills he would use throughout his career and, perhaps most importantly, steeled his resolve to learn what was needed to make a difference.

“I saw what a raw deal my students and their parents got, and how they didn’t have access to resources. To someone who had done nothing but the humanities in college, it was an eye-opening experience—but like students here at Marlboro, I had also learned how to learn, and my time in Thailand motivated me to learn about economics and politics. I wanted to make things a little better for people like the villagers I worked with.”

Kevin had an internship with the United Nations Development Program in Trinidad and Tobago, and earned his Master of International Affairs in economic and political development from Columbia University. Then, in Washington D.C., he oversaw foreign assistance agencies in President Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget and served as legislative director to U.S. Senator John Heinz, focusing on international financial and education issues. It was “a fabulous education inhow Washington and the world worked,” says Kevin, but the real watershed moment came in 1989, when he started as director of public policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Kevin had an internship with the United Nations Development Program in Trinidad and Tobago, and earned his Master of International Affairs in economic and political development from Columbia University. Then, in Washington D.C., he oversaw foreign assistance agencies in President Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget and served as legislative director to U.S. Senator John Heinz, focusing on international financial and education issues. It was “a fabulous education inhow Washington and the world worked,” says Kevin, but the real watershed moment came in 1989, when he started as director of public policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“It’s really rare in life that you can think of a problem or issue, and your first concern doesn’t have to be about resources,” says Kevin. “Although I hadn’t even heard of it before, at that time Pew was the second-largest foundation in the U.S., based on money out the door.” It was the end of the Soviet Union, the establishment of newly independent nations and economies in Central Europe, and all of the new leaders wanted access to Western ideas and resources. “Pew commanded the resources, so I got to meet many of the individuals, like Lech Walesa, Vaclav Havel, and others, who had a major impact on that democratization process.”

Following on his work in the former Soviet republics, Kevin published his book For Democracy’s Sake: Foundations and Democracy Assistance in Central Europe (Johns Hopkins University Press), in 1997. He was interested in how political and economic changes were effected, and what role outsiders have in encouraging or promoting such changes. Unlike after World War II, when the U.S. government helped rebuild Germany and Japan, there was no such appetite for public investment after the fall of the Berlin Wall. For better or worse, private foundations were the principal catalyst for change.

“I thought, this may be a completely unique experience in recent human history, a really interesting shift in what drives global change. I wanted to provide an opportunity for people at the forefront, leaders who were all so courageous, to assess what worked and what didn’t.” Kevin helped his colleagues in Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland organize case studies in each country, providing financial and technical support, translating the results into their national language, and discussing them in public forums.

During his time at Pew, Kevin completed his doctoral degree in comparative government at Georgetown University. He wanted to conduct his own research on social change, but rather than focusing on Central Europe—where there might be conflicts of interest with his foundation work—he went back to Thailand. There he knew the language and culture, and was very familiar with the national challenges of democratization.

During his time at Pew, Kevin completed his doctoral degree in comparative government at Georgetown University. He wanted to conduct his own research on social change, but rather than focusing on Central Europe—where there might be conflicts of interest with his foundation work—he went back to Thailand. There he knew the language and culture, and was very familiar with the national challenges of democratization.

“I was particularly interested in the role that civil society organizations play in creating democratic culture. Because unless you have the values of democracy, you can create the best independent parliament, the freest press, and it’s not going to mean anything. You need a culture that respects minority rights; encourages tolerance, empathy, and patience; has accountability and transparency. So how do you create that? There are really three mechanisms: governmental, market, and civil society, that vital space between markets and the public sector.”

Kevin went on to serve as vice president for business and policy at the Asia Society and Museum, in New York, and the first executive director for the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities, based in Baltimore, Maryland. In the latter role, he pioneered work withglobal companies like Nike and The Gap, the World Bank, and various universities and community-based organizations, seeking to improve the lives of production workers. He also launched his own consulting firm, called Q&A: Quigley & Associates, working for values-based organizations on strategy, program development, and resource mobilization issues.

In 2003 Kevin came full circle, so to speak, and began nearly 10 years of service as president and CEO of the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), the global alumni organization for 200,000 former volunteers and staff. There he developed a community-based model for the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary, using social media to spark the largest engagement ever, and established the More Peace Corps Campaign, resulting in the highest appropriation in the agency’s history—a $60 million increase. He also helped secure passage of the Peace Corps Commemorative Act, signed into law by President Obama.

In 2003 Kevin came full circle, so to speak, and began nearly 10 years of service as president and CEO of the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), the global alumni organization for 200,000 former volunteers and staff. There he developed a community-based model for the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary, using social media to spark the largest engagement ever, and established the More Peace Corps Campaign, resulting in the highest appropriation in the agency’s history—a $60 million increase. He also helped secure passage of the Peace Corps Commemorative Act, signed into law by President Obama.

During his time at NPCA, Kevin designed and secured endowment funding for the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award, which recognizes volunteers’ impact on individuals they serve. The award is named for one ofKevin’s mentors, Harris Wofford, the former senator, advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., and aide to President Kennedy, who was instrumental in the formation of the Peace Corps.

“Harris is kind of the godfather of service, in our country,” says Kevin, who has found inspiration in both Wofford and Sargent Shriver, statesman, activist, and the driving force behind the founding of the Peace Corps. “Both of them were always about the future. They were pragmatic idealists: they thought big, but could deliver, could make things happen to improve the lives of people.”

Throughout his career, Kevin has maintained a deep appreciation for and engagement with academia. He was a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow at 12 liberal arts colleges from 2004 to 2012, and a faculty-practitioner graduate instructor teaching about international studies and nonprofit management from 1995 to 2011. Earlier, he was guest scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the recipient of several other international professional fellowships. He has served on the board of Swarthmore College and the American University of Afghanistan.

Throughout his career, Kevin has maintained a deep appreciation for and engagement with academia. He was a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow at 12 liberal arts colleges from 2004 to 2012, and a faculty-practitioner graduate instructor teaching about international studies and nonprofit management from 1995 to 2011. Earlier, he was guest scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the recipient of several other international professional fellowships. He has served on the board of Swarthmore College and the American University of Afghanistan.

“Liberal arts education, especially in distinctive and academically rich settings such as Marlboro College, has a unique ability to anticipate change and prepare individuals for thoughtful, purposeful, and effective engagement in the world,” says Kevin. “What can you do with a liberal arts education? As my life suggests: anything and everything—it prepares you for a life unexpected.”

“For example, I’ve never had a course in economics and politics, and most of my life has been spent in those arenas. At its best, a liberal arts education stirs a passion for lifelong learning, looking at new opportunities as they come along, and making a difference. That’s what excites me, and that’s why I’m eager to make a contribution here at Marlboro.”

Kevin recognizes that Marlboro College is in a competitive environment, that small, independent, liberal arts colleges are under siege, and that many of them offer self-directed learning in small, interdisciplinary settings. But in his short time here so far he finds that what is most distinctive about Marlboro is the profound sense of community.

“Community has always been part of the ethos, and it’s reflected in the shared governance model. When people talk about shared governance in the liberal arts context, they’re talking about staff, faculty, and board—they’re not including students. While many liberal arts colleges share the objective of helping students become citizens of the world—and I’m a believer in experiential learning— I think Marlboro has a leg up because of our practices as a community.”

“Community has always been part of the ethos, and it’s reflected in the shared governance model. When people talk about shared governance in the liberal arts context, they’re talking about staff, faculty, and board—they’re not including students. While many liberal arts colleges share the objective of helping students become citizens of the world—and I’m a believer in experiential learning— I think Marlboro has a leg up because of our practices as a community.”

Kevin is looking forward to encouraging a more robust student life, including more activities on evenings and weekends and more interactions with local and global communities, as well as with the graduate campus in Brattleboro. “I see it in our culture, I see it in our heritage, but we have to have the programs that reflect the importance of community at Marlboro,” he says.

“I think of community as having shared values and experiences and aspirations. As community members we get opportunities and privileges, but we also have some responsibilities to other people. How do I express my gratitude at being a member of community? How do I fulfill part of my obligations? Service is a great way to do it, and it’s particularly powerful in an educational context, because service helps us learn life lessons and is the gift that keeps on giving.”

Celebrating President Kevin  Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

“Although change is never easy, Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher, teaches us that change is an entirely natural process since ‘no one steps into the same river twice,’” said Kevin in his inaugural address, titled “Marlboro Matters: The Engaged Marlboro Community of the Future.”

“The Marlboro of today is different from the Marlboro of yesterday and will be from the one of tomorrow. That river flows on, and we all must necessarily evolve with the flow. Our very engaged and amazingly supportive board has responded creatively and quickly to current challenges— again supporting how much Marlboro matters.

“Over the past few months, I have come to more deeply appreciate the fact that Marlboro matters because it continues to teach invaluable, timeless skills that have broad applicability: to think critically, to read closely, to communicate compellingly, to work in community.

“Over the past few months, I have come to more deeply appreciate the fact that Marlboro matters because it continues to teach invaluable, timeless skills that have broad applicability: to think critically, to read closely, to communicate compellingly, to work in community.

“Liberal arts, as the Greeks first posited, and as it is more recently argued by public intellectuals like Fareed Zakaria, is the best preparation for an engaged life and citizenship. As my life suggests, liberal arts graduates can do anything and everything, everywhere. There is also growing evidence from leading corporations, that they want liberal arts graduates because they work well across disciplines, problem solve, and communicate in ways that some other graduates can’t.”

For more excerpts, photos, and video from the ceremony, go to marlboro.edu/inauguration.

For more excerpts, photos, and video from the ceremony, go to marlboro.edu/inauguration.

Semester intensive reframes addiction debate

“With the recent spike in heroin overdoses in rural white America, addiction is getting a lot of attention,” says politics professor Meg Mott. “Governor Shumlin made it the sole concern of his 2014 State of the State Address. I thought it would be a good time to step back from the debate and look at how the speeches and campaigns were being framed.”

“With the recent spike in heroin overdoses in rural white America, addiction is getting a lot of attention,” says politics professor Meg Mott. “Governor Shumlin made it the sole concern of his 2014 State of the State Address. I thought it would be a good time to step back from the debate and look at how the speeches and campaigns were being framed.”

The result is Speech Matters, a new semester intensive launched by Meg this fall, which uses the humanities to delve deeply into and reframe a national issue, in this case addiction. Following the full-on, focused model pioneered by Movies from Marlboro, Speech Matters is taking one group of students through the political, economic, cultural, and racial aspects of addiction in America. In the process, each student is learning to communicate their ideas in nuanced but compelling ways and building a professional portfolio of blog posts, podcasts, op-eds, and other media content.

“The questions being posed in the current debate tend to ignore the larger structural reasons for drug use: in a town with no jobs, selling drugs is far more lucrative than panhandling,” says Meg. “In a nation with reduced social services, using drugs dulls the pain of losing custody of one’s child, not getting a callback on a job interview, or having to wait through the winter for a Section 8 voucher. By focusing on the ‘addict,’ we don’t look at the bad decisions made by policy makers, who often seem to be ruled by corporate interests.”

Meg draws inspiration for the Speech Matters program from her grandfather Archibald MacLeish, a librarian of congress, assistant secretary of state, and Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, who put as much emphasis on how things were said as on what was being said. “Archie spent enough time working for the government to know how speech could humanize or dehumanize a part of the population,” she says. “He got poet Ezra Pound out of St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital by arguing for the poet against claims that Pound was no more than a ‘crazy fascist.’”

Meg draws inspiration for the Speech Matters program from her grandfather Archibald MacLeish, a librarian of congress, assistant secretary of state, and Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, who put as much emphasis on how things were said as on what was being said. “Archie spent enough time working for the government to know how speech could humanize or dehumanize a part of the population,” she says. “He got poet Ezra Pound out of St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital by arguing for the poet against claims that Pound was no more than a ‘crazy fascist.’”

Students in Speech Matters will consider what it would look like to reframe addiction in human terms. “Instead of talking about people who use drugs as if they are deviant or different,” explains Meg, “critical theory asks us to consider who benefits from the creation of a class of ‘addicts.’” By investigating the history of drug policy and the cultural values embedded in the rhetoric of prevention, recovery, and treatment, Meg anticipates that more humanistic discussions of drug use will emerge.

“The most exciting thing for me is that we’ll be applying the skills of the humanities to an emerging political situation,” says Meg. “Right now, the 12-step programs are under scrutiny because of the Affordable Care Act, and ‘Big Pharma’ is moving in to support medication-assisted treatments. This is a very exciting time to think critically about who benefits from the existing narrative about addiction and what new, more community-based narratives might emerge.”

Jean O’Hara brings social change to theater

“I’m interested in how theater creates dialogue and new understandings,” says Jean O’Hara, who joined Brenda Foley as theater faculty last spring semester. Jean comes to Marlboro with two decades of teaching and directing experience, ten years in higher education, and a wealth of knowledge in areas of high interest to students, including political theater, environmental justice, and gender studies.

“Everything about Marlboro attracted me to Marlboro,” says Jean. “I love the fact that it has a smaller number of students, and that students have the freedom to choose what they want to study and take classes they are interested in—those are the best kind of students. At the same time, faculty can teach what they are passionate about— this is an amazing and rare opportunity as more and more universities are standardizing their curricula. I really love that Marlboro allows that freedom on both ends.”

Jean received her bachelor’s degree from Rhode Island College, her master’s from Humboldt State University, and her PhD from York University, with a dissertation that explores how two-spirit plays challenge the dominant narrative about gender and sexuality. She is also the editor of the anthology Two-Spirit Acts: Indigenous Queer Performances, and says that studying Indigenous societies has radically changed the way she views gender.

“Although I’ve been examining gender and gender politics for a long time, two-spirit scholarship radically shifted my worldview. The colonial tactics of annihilation of gender variance within Native communities was directly linked to the division of communally held land of Native nations. The communal system was replaced by individually owned property passed through the male bloodline. I believe we, both Native and non-Native people, are still living with the effects of this system, which created a binary and hierarchy between all genders.

Jean uses her work to investigate themes of racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and heterosexism, and believes in the power and efficacy that theater has to give voice to traditionally marginalized groups. Having worked with both the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, Jean credits Boal with laying the foundation for her own pedagogy, for seeing students as agents in the classroom. “We need to come from a place of equality in order to freely learn and create, versus working in hierarchical frameworks,” Jean says.

Jean is passionate about using theater as a venue for environmental justice, and for creating and maintaining local food sources. She co-edited and co-directed the play Salmon is Everything, which encouraged unity among farmers, ranchers, fishermen, and Native communities to all work for a cleaner river and healthy salmon runs in California and Oregon’s Klamath Basin.

“Having helped co-create Salmon is Everything, and bringing it out to reservations, really showed me the power of storytelling on another level,” says Jean. “To have non-Native community members and Native people from three different nations all working together to help keep the river healthy for everyone was really powerful. The play actually helped with that coalition— instead of all fighting for water, farmers and ranchers and fishermen and Native people were all looking at the bigger issue, which were the dams that stopped the flow of water. I’m proud that the play helped lead to legislation for those dams to come down.”

Last spring, Jean incorporated the community greenhouse into her class called Eco-Drama: Staging the Environment and Community, which culminated with harvesting their produce and making a meal combined with produce from other local farmers. She’s interested in local food and the slow food movement as a sustainable alternative to the present “megafood industry,” which is harmful to the land, animals, and workers.

This fall semester, Jean is offering two one-credit courses called Theater in the Wilds, which combine theater exercises with an outdoor adventure—a rafting trip and a backpacking trip, respectively. She is also collaborating with Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson to present Teatreras y Directoras, a course about Latin women who make theater and films exploring identity, family, citizenship, and class, among other topics.

“I see theater and storytelling as an important way to connect, build community, and create a much-neededto be heard,” she says. “I’m excited about co-creating with Brenda a really engaging theater program in the next few years. We are thrilled about our connection with the Vermont Performance Lab, and looking forward to incorporating Marlboro College theater more into the community.”

For Marlboro students interested in theater, Jean suggests exploring every aspect of the discipline, from playwriting to design, from acting to directing. “I think it’s really important for every theater artist to read and attend plays to expand how they view and present stories. She also suggests that students take risks in classes and on the stage. “Theater is such a gift of opening up your world and creating deep intimacy—it will change you in ways you never imagined.”

Also of Note

At the final Town Meeting last spring, the library announced that the annual “Check Me Out” Award, for checking out the most books in an academic year, went to Emily Tatro ’16. Emily smoked the opposition by taking out a stunning 103 books in the pursuit of her intellectual interests. While Marlboro College students take out an average of 52 books a year from the library, the national average for college students is 12.

At the final Town Meeting last spring, the library announced that the annual “Check Me Out” Award, for checking out the most books in an academic year, went to Emily Tatro ’16. Emily smoked the opposition by taking out a stunning 103 books in the pursuit of her intellectual interests. While Marlboro College students take out an average of 52 books a year from the library, the national average for college students is 12.

Louisa Jenness ’15 passed the highest level of the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi, a Chinese proficiency test for non-native Chinese speakers and the only international standardized exam recognized by the Republic of China. She passed level VI, which means she has a vocabulary of more than 5,000 characters and can effectively express herself both orally and on paper.

In February, sophomore Chris Lamb competed at the Harris Hill ski jumping competition in Brattleboro. Chris first competed at Harris Hill at the age of 11 and still holds the record for the longest jump there, at 102 meters, set in 2010. “It’s like learning how to ride a bike—you don’t forget,” said Chris. During the competition the announcers nicknamed him “the Professor,” because they saw him reading Immanuel Kant.

Benchmarks for a Better Vermont, a program of Marlboro’s Center for New Leadership (CNL), sponsored a training geared specifically for results-based accountability (RBA) trainers in April. Results expert Deitre Epps led the program, which was attended by a diverse group with deep experience in Vermont, and from as far away as Florida and Australia.

Theresa Chockbengboun ’15 (pictured right) was awarded a Fulbright U.S. Student Program grant to teach English at a university in Laos, while pursuing research opportunities in public health. “I’m excited to spend an entire year in another country and to learn about their culture and unique challenges in facing the future,” said Theresa. She did her Plan on public health in Southeast Asia, including an investigation of water quality and the use of “biosand” filters in Cambodian villages.

In April, seniors Edward Suprenant and Christian Lampart attended the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium at Green Mountain College. Edward presented a paper about the tendency toward essentialism in historical studies of Buddhist traditions. “The idea that there is an essential practice or idea throughout history that is Buddhist is completely against the practices and ideas of Buddhism,” says Edward. Meanwhile, Christian presented a paper on Orthodox Christianity.

With support from a summer internship grant, senior Felix Jarrar spent his summer workshopping a new opera, The Fall of the House of Usher. Based on Edgar Allan’ Poe’s story by the same name, Felix’s opera tells the famed gothic tale from the perspective of Lady Madeline. The main project for his Plan of Concentration, the opera will be premiered next March at Marlboro and at the DiMenna Center in New York City. Learn more.

Events

1 During Earth Week, politics professor Meg Mott brought in a tribe of baby goats for a little much-deserved goat therapy, here enjoyed by Sarah Palacios ’17. 2 Acclaimed geophilosopher David Abram (pictured right, with philosophy professor William Edelglass and Aidan Keeva ’15) gave an engaging talk titled “Between the Body and the Breathing Earth.” 3 Local artist Betsy MacArthur presented a show of her private journals and other work called Turning the Pages. 4 A screening of Peter and John, the new film by professor Jay Craven, created as part of the Movies from Marlboro intensive, took place at the Latchis Theatre in April. 5 In February, the annual Wendell-Judd Cup hosted a good crowd including young Will Koch, the cup winner this year and son of Olympic medalist and Wendell-Judd record holder Bill Koch. 6 The Bamidele Dancers and Drummers gave a concert in Ragle Hall in February, presenting music and dance from Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean. 7 In April, Connecticut College professor Suffia Uddin presented a talk called “Interrogating Our Own Questions about Muslim Women, Islam, and the Veil."

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

Photography professor John Willis was visited by junior Shannon Haaland to talk about teaching, his latest work, and how new students help keep his own vision fresh. You can read the whole interview.

Shannon Haaland: What do you like most about working with Marlboro students?

John Willis: Marlboro students designing their own Plans of Concentration bring their interests to the table, so I am always learning about different relationships and different topics and different contemporary issues. It keeps it really exciting. I love the time of year when I get so busy I don’t sleep regular nights, like Plan students.

SH: So, students still surprise you with their work?

JW: Honestly, even intro class students surprise me with their work, and intro is where you are trying to teach promising new students the same fundamental subject matter, every semester. It seems like it would be incredibly repetitive, but what always makes it surprising is that every student comes to it with a different mind and different abilities, and creates different images.

SH: Have students helped you in your own work process?

JW: Well, I get a lot out of working with students— the whole thing of not looking at everything the same way, and trying to experience the world differently. I learn as much about keeping an open mind from seeing how students approach things as from anywhere else.

SH: How have Marlboro students helped out with your work at Pine Ridge Reservation?

JW: Exposures—the cross-cultural youth summer program based in Brattleboro, part of the In-Sight Photography Project—was created with five Plan students. I don’t think it would have ever happened if it wasn’t for this group of students that decided they were going to do this together, without pay or credits. Whenever there is a student interest strong enough it just sort of bubbles up.

Learn more about Exposures at exposuresprogram.org. Photo by Kelly Fletcher

Focus on Faculty

“I think about how the Buddha said—something to the effect of—‘We have to live in the world as if we can make a difference, even though we will never know if we really do,’” said photography professor John Willis at a gallery talk in March. “It’s important to me to think about, ‘Can I make a difference with photography, and the way that I live my life?’” The talk was part of his exhibit of recent photography at Greenfield Community College, titled House/Home: A Work in Progress, which documents the housing conditions on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. See his gallery talk.

Cultural history professor Dana Howell has completed her work with the Open Society Foundations. The program she worked on, Regional Seminar for Excellence in Teaching, has concluded after 12 years as OSF (formerly OSI) shifts its attention elsewhere. Dana began her work with OSF in 2000, leading a visiting evaluation team to the first liberal arts college in Russia, Smolnyi College. Also of note, Dana’s book The Development of Soviet Folkloristics is being reissued by Routledge as part of a series of library editions on folklore. First published in 1992, the book is a key reference on the development of folklore study in the Soviet Union. Learn more.

“Volunteering is something I started doing at a very young age,” says MSM-MDO faculty member Julie van der Horst Jansen in a recent interview on the United Way of Windham County website. In the interview, Julie describes her work with the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program, which provides free federal and state income-tax preparation services to eligible taxpayers. “There is real caring in this community,” Julie says. “Volunteering, in general, is one of those rare opportunities where you get back what you put in. It’s satisfying and gratifying to be a volunteer: you can enjoy the work and meet new people.” See her interview.

Marlboro’s social science fellow last year, anthropologist Alison Montgomery, was awarded a prestigious Science and Technology Policy Fellowship from the American Association for the Advancement of Science for this academic year. The fellowship provides the opportunity for accomplished scientists like Alison to participate in, and contribute to, the federal policy-making process while learning firsthand about the intersection of science and policy. Marlboro wishes Alison all the best.

“At first glance, the political-theory classroom can seem like a ‘philosophy class in disguise,’” says politics professor Meg Mott in the abstract of her article in the July issue of PS: Political Science & Politics. Titled “Want to Study the Nature of Power? Start by Moving the Chairs!” Meg’s article explores how teachers can make their text-based classes more “political.” She considers how different teaching formats enact different types of power in the classroom, in turn necessitating political judgments. “By physicalizing the argumentative, introspective, and descriptive devices that writers of political theory use, students become better readers of these often old and usually dense texts,” says Meg. Read more.

In March, Chelsea Green Publishing released The Social Profit Handbook, by David Grant, faculty member in the Center for New Leadership’s Board Leadership Institute and Certificate in Nonprofit Management programs. The book offers those who lead, govern, and support mission-driven organizations and businesses new ways to assess their impact in order to improve future work, rather than merely judge past performance. Assessment doesn’t have to mean piles of quantitative data, says David, the former president and CEO of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. “If you can describe it in words, you can measure it.”

“Marlboro College music professor Stan Charkey has written a new work, and it’s one that poignantly brings to life quiet moments from Vermont’s history,” writes Kari Anderson, managing producer for VPR Classical. Stan was interviewed by VPR in April regarding Vermont Headstones, his cycle of 12 songs for baritone, oboe, and viola that uses poetic inscriptions from historic Vermont cemeteries for the lyrics. The piece had its world premiere at Marlboro College last November, to glowing reviews. In April, Stan joined Kari to talk about what inspired Vermont Headstones, and the previously unsung Vermonters whose stories became songs. Read more.

“Vermont education pioneer John Dewey called for the ‘full participation with all our powers in the endeavor to wrest from each situation its own full meaning,’” says film and video studies professor Jay Craven. An award-winning independent filmmaker, co-founder of Kingdom County Productions, and director of the Movies from Marlboro semester intensive, Jay was invited to be the commencement speaker at Burlington College last May. He was also awarded an honorary degree in recognition of his contributions to the local and broader artistic communities. “Jay has opened the world of the arts and film to the citizens of the Kingdom and beyond,” says Burlington College President Carol Moore.

In May, visual arts faculty Cathy Osman and Tim Segar were featured in a group show at the Oxbow Gallery, in Northampton, Massachusetts. Titled Synecdoche: Simultaneous Understanding, the show included the work of eight Oxbow artists, and was curated by Deborra Stewart-Pettengill. For those unfamiliar with the term, synecdoche is a figure of speech similar to metonymy, in which a part is made to represent the whole, or vice versa. The Oxbow Gallery is a collective gallery owned and operated by 35 artist-members, showcasing a variety of fine art techniques and mediums.

And the winner is…Jim, Tim, and Todd. Computer science professor Jim Mahoney, visual arts professor Tim Segar, and chemistry professor Todd Smith were the proud winners of a LulzBot Mini v1.0 3D printer, as part of the first annual LulzBot Education Giveway sponsored by parent company Aleph Objects. The printer, which turns plastic filaments into three-dimensional shapes based on computer-aided designs, can be used by students in all areas of study. “We are excited to house the 3D printer in the new Snyder Center for the Visual Arts, which is intended for cross-disciplinary interaction,” said Todd. Kudos to campus store manager Rebecca Bartlett ’79 for alerting faculty to the competition.

“I cannot account for my mother. She is too many,” writes the inimitable literature and writing professor John Sheehy, who published a nonfiction story in the July/August issue of the online literary magazine Eclectica (Vol. 19, No. 3). Titled “To Thee Do WeCry,” John’s story reflects on the life and relationships of his mother, Rita, on the occasion of her funeral. John has previously published nonfiction in Fourth Genre, and had a story in the book The Good Men Project. Read his story.

In May, Karen White’s book Practical Project Management for Agile Nonprofits was awarded the bronze award for nonprofit books in the eighth annual Axiom Business Book Awards. Karen is a faculty member in the MSMMDO program and program chair for both the MSM in Health Care Management and MSM in Project Management programs. Karen’s second book, Practical Project Management offers useful approaches and templates for project managers to best maximize limited resources. “According to our publisher, it went up against books from some major publishing houses and was very well received for its practicality and applicability,” says Karen.

Last fall, Potash Hill reported that visual arts faculty members Cathy Osman, Tim Segar, and John Willis were launching a website and other efforts to support the Khmer Children’s Education Organization (KCEO), a family-run school in rural Cambodia. This year KCEO has been recognized with a commitment for ongoing assistance from the World Vision Organization, but they still need to raise their own percentage of the budget to receive this assistance. Cathy, Tim, John, and John’s wife, Pauline Brett, are on the school’s advisory board, and are encouraging other community members to help: even small donations can make a substantial difference. Learn more and contribute at khmerchildren.org.

In May, theater professors Jean O'Hara and Brenda Foley and junior Rainbow Stakiwicz participated in a weeklong residency with Spiderwoman Theater, the oldest Native women’s theater ensemble in North America. Based at the University of Oregon, the week of Indigenous-centered theater-making built upon Jean’s previous close collaborations with host Theresa May and Muriel Miguel, artistic director of Spiderwoman Theater. The residency showcased Indigenous theater as a medium to address Native communities’ relationship to rivers, while highlighting traditional environmental knowledge and understandings of sexuality and gender. In July, Jean collaborated again with Muriel Miguel on a Native theater intensive sponsored by the Centre for Indigenous Theatre.

Breaking out of unemployment and into a restaurant job in Brattleboro got easier this year, thanks to Tristan Toleno, faculty member in the MBA and MSM-MDO programs. Tristan was the resident chef for the “Farm to Plate” Culinary Apprenticeship Program, a 12-week program designed to lead to permanent food preparation positions and sponsored by the Strolling of the Heifers. The program offered its 12 participants basic food preparation skills from knife safety to culinary mathematics, management skills, job readiness skills, and on-the-job training in local restaurants and institutional kitchens. It was free to participants who met income and employment status qualifications, including veterans.

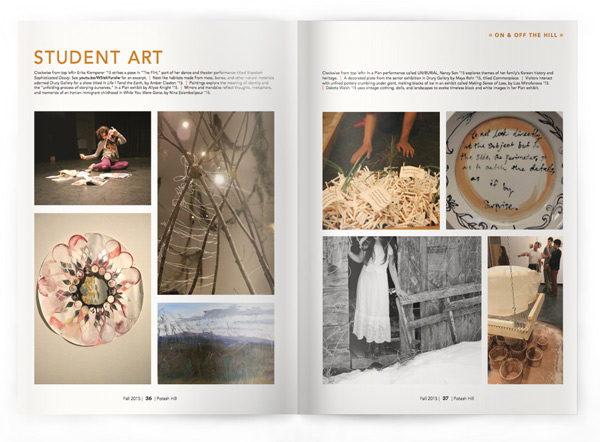

Student Art

Left page, clockwise from top left> Erika Klemperer ’15 strikes a pose in “The Flirt,” part of her dance and theater performance titled Slapdash Sophisticated Doozy. See youtu.be/W5IekYurolw for an excerpt. | Nest-like habitats made from moss, bones, and other natural materials adorned Drury Gallery for a show titled In Life I Tend the Earth, by Amber Claxton ’15. | Paintings explore the meaning of identity and the “unfolding process of storying ourselves,” in a Plan exhibit by Allyse Knight ’15. | Mirrors and mandalas reflect thoughts, metaphors, and memories of an Iranian immigrant childhood in While You Were Gone, by Nina Eslambolipour ’15.

Right page, clockwise from top left> In a Plan performance called UN/BURIAL, Nancy Son ’15 explores themes of her family’s Korean history and heritage. | A decorated plate from the senior exhibition in Drury Gallery by Maya Rohr ’15, titled Commonplace. | Visitors interact with unfired pottery crumbling under giant, melting blocks of ice in an exhibit called Making Sense of Loss, by Liza Mitrofanova ’15. | Dakota Walsh ’15 uses vintage clothing, dolls, and landscapes to evoke timeless black and white images in her Plan exhibit.

2015 Undergraduate Commencement

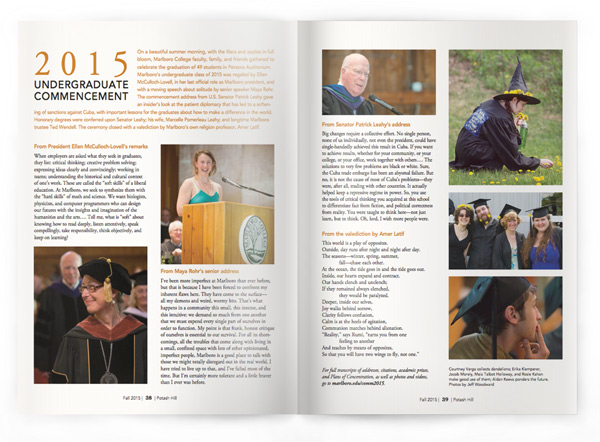

On a beautiful summer morning, with the lilacs and apples in full bloom, Marlboro College faculty, family, and friends gathered to celebrate the graduation of 49 students in Persons Auditorium. Marlboro’s undergraduate class of 2015 was regaled by Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, in her last official role as Marlboro president, and with a moving speech about solitude by senior speaker Maya Rohr. The commencement address from U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy gave an insider’s look at the patient diplomacy that has led to a softening of sanctions against Cuba, with important lessons for the graduates about how to make a difference in the world. Honorary degrees were conferred upon Senator Leahy; his wife, Marcelle Pomerleau Leahy; and longtime Marlboro trustee Ted Wendell. The ceremony closed with a valediction by Marlboro’s own religion professor, Amer Latif.

On a beautiful summer morning, with the lilacs and apples in full bloom, Marlboro College faculty, family, and friends gathered to celebrate the graduation of 49 students in Persons Auditorium. Marlboro’s undergraduate class of 2015 was regaled by Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, in her last official role as Marlboro president, and with a moving speech about solitude by senior speaker Maya Rohr. The commencement address from U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy gave an insider’s look at the patient diplomacy that has led to a softening of sanctions against Cuba, with important lessons for the graduates about how to make a difference in the world. Honorary degrees were conferred upon Senator Leahy; his wife, Marcelle Pomerleau Leahy; and longtime Marlboro trustee Ted Wendell. The ceremony closed with a valediction by Marlboro’s own religion professor, Amer Latif.

From President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s remarks

When employers are asked what they seek in graduates, they list: critical thinking; creative problem solving; expressing ideas clearly and convincingly; working in teams; understanding the historical and cultural context of one’s work. These are called the “soft skills” of a liberal education. At Marlboro, we seek to synthesize them with the “hard skills” of math and science. We want biologists, physicists, and computer programmers who can design our futures with the insights and imagination of the humanities and the arts…. Tell me, what is “soft” about knowing how to read deeply, listen attentively, speak compellingly, take responsibility, think objectively, and keep on learning?

From Maya Rohr’s senior address  I’ve been more imperfect at Marlboro than ever before, but that is because I have been forced to confront my inherent flaws here. They have come to the surface— all my demons and weird, wormy bits. That’s what happens in a community this small, this intense, and this intuitive: we demand so much from one another that we must expend every single part of ourselves in order to function. My point is that frank, honest critique of ourselves is essential to our survival. For all its shortcomings, all the troubles that come along with living in a small, confined space with lots of other opinionated, imperfect people, Marlboro is a good place to talk with those we might totally disregard out in the real world. I have tried to live up to that, and I’ve failed most of the time. But I’m certainly more tolerant and a little braver than I ever was before.

I’ve been more imperfect at Marlboro than ever before, but that is because I have been forced to confront my inherent flaws here. They have come to the surface— all my demons and weird, wormy bits. That’s what happens in a community this small, this intense, and this intuitive: we demand so much from one another that we must expend every single part of ourselves in order to function. My point is that frank, honest critique of ourselves is essential to our survival. For all its shortcomings, all the troubles that come along with living in a small, confined space with lots of other opinionated, imperfect people, Marlboro is a good place to talk with those we might totally disregard out in the real world. I have tried to live up to that, and I’ve failed most of the time. But I’m certainly more tolerant and a little braver than I ever was before.

From Senator Patrick Leahy’s address

Big changes require a collective effort. No single person, none of us individually, not even the president, could have single-handedly achieved this result in Cuba. If you want to achieve results, whether for your community, or your college, or your office, work together with others…. The solutions to very few problems are black or white. Sure, the Cuba trade embargo has been an abysmal failure. But no, it is not the cause of most of Cuba’s problems—they were, after all, trading with other countries. It actually helped keep a repressive regime in power. So, you use the tools of critical thinking you acquired at this school to differentiate fact from fiction, and political correctness from reality. You were taught to think here—not just learn, but to think. Oh, lord, I wish more people were.

From the valediction by Amer Latif  This world is a play of opposites.

This world is a play of opposites.

Outside, day runs after night and night after day.

The seasons—winter, spring, summer, fall—chase each other.

At the ocean, the tide goes in and the tide goes out.

Inside, our hearts expand and contract.

Our hands clench and unclench;

If they remained always clenched, they would be paralyzed.

Deeper, inside our selves,

Joy walks behind sorrow,

Clarity follows confusion,

Calm is at the heels of agitation,

Communion marches behind alienation.

“Reality,” says Rumi, “turns you from one feeling to another

And teaches by means of opposites,

So that you will have two wings to fly, not one.”

Find full transcripts of addresses, citations, academic prizes, and Plans of Concentration, as well as photos and videos, on the website.