Spring 2016

Editor’s Note

Civic engagement is something people tend to take seriously at Marlboro College. Whether it’s working with Cambodian villagers to improve their drinking water or finding the resources for a skateboard ramp on campus, community members show up and make their voices heard. Marlboro attracts students who are not only academically curious but devoted to intellectual freedom, excited by our model of self-governance, and engaged in community-building.

Civic engagement is something people tend to take seriously at Marlboro College. Whether it’s working with Cambodian villagers to improve their drinking water or finding the resources for a skateboard ramp on campus, community members show up and make their voices heard. Marlboro attracts students who are not only academically curious but devoted to intellectual freedom, excited by our model of self-governance, and engaged in community-building.

This issue of Potash Hill is chock full of civic engagement, from a feature about collective action by politics professor Meg Mott to an editorial on challenging war with imagination from film professor Jay Craven. From senior Kelly Hickey’s exploration of second-wave feminism in Vermont to a timely campus celebration of the Americans with Disabilities Act, this issue is, well, full of issues.

Students meeting with trustees to discuss renewal, change, and what they value most about Marlboro—check. A panel of faculty discussing the alarming fate of North African nations in the wake of the Arab Spring—check. A new book by alumnus Charles Curtin on conserving large, complex ecological systems—yup. We even welcome two community-oriented faculty members: Nelli Sargsyan, who explores the anthropology of social movements, and Roberto Lugo, who uses ceramics to challenge cultural intolerance. You can find it all in this action-packed Potash Hill.

In the words of President Kevin, who joined our community in July 2015 and has not sat idle for five minutes since, colleges like Marlboro “prepare individuals for thoughtful, purposeful, and effective engagement in the world” (Potash Hill, Fall 2015). The Renaissance Scholars program he initiated last year, with the eager support of the community, is making it easier to find the “rugged intellectuals” that will be actively engaged on campus and in the world. Learn more at goo.gl/vFgohZ.

What are you doing to “think outside the cave?” Where has your “road less traveled” led you, and where are you leading your community? We are eager to hear your responses to this issue, and your own stories of engagement.

—Philip Johansson, editor

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the undergraduate campus was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Ella McIntosh

Staff Photographers: Ben Rybisky ’18 and Lindsay Stevens ’17

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: A massive, welded sculpture by Colin Leon ’15, part of his Plan show in December 2015, gives a palpable sense of opposing forces, dynamic balance, and engagement. Learn about Colin’s recent work on a kinetic sculpture at Burning Man 2015 on page 28.

The class of 2015 put their money where their mouths enjoyed copious cappuccinos and deep-fried comfort food, with a class gift of new stools for the renovated campus center coffee shop, known as “Potash Grill.” Stop by whenever you have a hankering for a hummus wrap or a maple latte. Or see a recent video about the coffee shop by student Matteo Lanzarotta ’18.

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our undergraduate campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, and our graduate center in Brattleboro, students engage in deep exploration of their interests—and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

Up Front

4-Square Rules | A mere sampling:

Black Knight> If a player can catch the ball cleanly between their two hands before it bounces, the player that last hit the ball is out.

Leaping Knight> A variant of Black Knight where the catch only counts if the player is in the air when they grasp the ball. Otherwise, the player is out.

Dark Knight> Another variant of Black Knight where the catch only counts if the player can catch the ball with their elbows (like a bat).

Coup d’Etat> If a player can get the king out without the king touching the ball, they then become king.

People’s Serve> Any player can serve the ball. Don’t fight over it too much.

The Unforgivable Curses> A player may hit the ball on the first, second, or fourth bounce. If the ball is hit on the third bounce, that player is out.

Exile> Players may not touch their squares with their feet. Hands and other body parts are permitted.

Serenade> The player in first square must serenade the king with a song of their choice.

Quaker> All players, active and nonactive, must end their sentences with the word friend. They also must not curse.

Brooklyn> Everyone needs to be rude to each other and use at least one swear in each sentence.

We the People> In order for a rule to pass, all players must get a majority vote.

Double Talk> A rule that is specifically designed for arguing over whether the game requires it or not. It is the most important rule of the game.

Clear Writing

The Corridor of Trauma

By Haley Peters ’15

In 1881, just after novelist and essayist Virginia Woolf was born, her father Leslie Stephen purchased Talland House, a small house on the outskirts of St. Ives, Cornwall, as a vacation home for his growing family. The family enjoyed the home until the death of their mother in 1895. Then they let the home go. Ten years later, after Woolf endured the traumatic loss of her half-sister and of her father, Woolf and her sister Vanessa visited the home. The house was lit and occupied. They said they “felt like ghosts” themselves. Twenty-two years after that visit, in 1927, on the other side of three losses and several complete mental breakdowns, Woolf published her novel about another traumatized family and their house: To the Lighthouse.

The story is told in three parts. The first and third parts each describe a day at a house owned by the Ramsays—the first in 1910 and the second in 1920. The second section describes the passage of ten years between these two days. In a small journal labeled “Notes for writing,” Virginia Woolf imagined her novel as “two blocks joined by a corridor.” The blocks on either side represented the first and third sections of the novel, “The Window” and “The Lighthouse”; the corridor represented the intervening section, “Time Passes,” which encompasses ten years, a war, and three deaths. Woolf knew personally the devastation trauma causes to a person’s fundamental assumptions about the world. However, by challenging those assumptions, by forcing a person to rewrite their personal narrative and rethink the framework by which they make meaning of their world, trauma creates growth. We see the Ramsay family as they exist in two spaces of time, on either side of ten years of grief and trauma. On either side of the corridor, a guest in the house named Lily attempts to make a picture. Meanwhile, we witness three pictures of the Ramsay family: a family before trauma, the dark senselessness endured by the traumatized family, and the family members who survived and grew.

This excerpt comes from Haley Peters’ Plan of Concentration in literature and writing, titled “‘The Dark Voicelessness in Which the Words Are the Deeds’: Considering Death and Grief through Reading and Writing.” You can find excerpts from other recent Plans, from “The Dirt on Mutualism” to “Layers of Legality: Interactions between State Law, International Law, and Shariah,” in the Virtual Plan Room. Photo by Kelly Fletcher

Letters

Road to Citizenship I have had such pleasure reading the most recent Potash Hill (Fall 2015) and rejoicing that the college is still going strong. All the faces are new, with exception to Tom Ragle and Ellen, as are many of the buildings. I am so impressed with the current roster of faculty, Kevin Quigley as our new president, and students.

I have had such pleasure reading the most recent Potash Hill (Fall 2015) and rejoicing that the college is still going strong. All the faces are new, with exception to Tom Ragle and Ellen, as are many of the buildings. I am so impressed with the current roster of faculty, Kevin Quigley as our new president, and students.

I continue to talk to younger people and tell them how important a college degree from a liberal arts college is, no matter what path you want or end up taking in the future. Some of us never had a career, so to speak, but delved into many and varied interests: from Greek classics to volunteer coordinator, to political research analyst, to sheep herder, to certified tree farmer. Along this path, there were hundreds of hours of volunteering for the Greek Resistance, Friends of the Library, hospice care, and as chair of the county No One Dies Alone committee. Most recently I have been appointed trustee to the State Library of Oregon.

I have to credit Marlboro College, as well as Catlin Gabel School in Portland, Oregon, for giving me the tools and time to become a better citizen, working to make my local community—wherever it has been—healthier and more aware of the external world. And before I forget: the major topics for Town Meeting in my time were parietal hours, pets on campus, and dance weekends.

—Jennie Tucker ’67

Potash Thrills

I’m so pleased with how the redesign of Potash Hill came through last year. When I opened my email today to see the cover of the last issue, my heart dropped and I had goosebumps from how beautiful the image on the front cover is. I promise to revisit the hill sometime. Congratulations on another incredibly successful publication.

—Elisabeth Joffe ’14

Just tore through my Fall 2015 copy of Potash Hill, and wanted to let you know I felt completely comfortable, and at times very happy, with the new design (even though I still miss the sparse, elegant old black-and-white version). I was very touched by Lucy DeLaurentis’ tribute on the last page. I’m not sure if I ever met Lucy, but I think of her often.

Just tore through my Fall 2015 copy of Potash Hill, and wanted to let you know I felt completely comfortable, and at times very happy, with the new design (even though I still miss the sparse, elegant old black-and-white version). I was very touched by Lucy DeLaurentis’ tribute on the last page. I’m not sure if I ever met Lucy, but I think of her often.

—Pearse Pinch ’14

What a splendid issue of Potash Hill. The cover is astounding in its simplicity, its beauty, and its refusal to do the usual alumni magazine schtick. What gorgeous graphic design, throughout. Surely, if there is an award for alumni magazines out there, you deserve something for your style and elegance.

—William Morgan, friend

Inaugural Impressions

I think the Peace Corps–inspired day of service that was part of President Quigley’s inauguration was a great idea. It’s the kind of gesture that is emblematic, we all hope, of his activist first year as president. I also want to applaud him and the college for initiating the multifaceted Renaissance Scholars program. It’s fresh, inspirational, and innovative, plus it appears to draw on his own professional and personal experiences, and this will only give it the staying power it merits.

—David Lincoln Ross ’76

In response to some uncertainty stimulated by President Quigley’s inaugural speech, I can attest that poet Robert Frost was indeed a trustee of Marlboro College, the very first. That trip I took with my father to visit Frost and share his idea of starting the college was specifically to ask him to be a trustee. If there’s any doubt, there is a book of Frost’s poems in my father’s library inscribed: “To Walter, from his trusting but untrustworthy trustee.” My father also got Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Dorothy Thompson, and George Whicher, English professor at Amherst, to be on the board soon after, because he wanted creative thinkers to make up the board beside the traditional lawyers and bankers.

— Geoffrey Hendricks, friend, and son of founder Walter Hendricks

Rankling Racism

Even after several years, I still find it tactless and upsetting that the Summer 2012 issue of Potash Hill quoted this Marlboro Citizen personal ad: “I’m looking for a new best friend. Candidates should be Jewish, neurotic Freudians, and pathological narcissists.” I am certain that if stereotypes about other ethnic or religious groups replaced “Jewish,” and said something like “Candidates should be African-American, loose-fingered, high-jumping rappers and pathological car-jackers” or “Arabs, easily offended, overly attached to concepts of honor, and pathological terrorists,” there would be a loud outcry about racism and stereotyping, and rightfully so. I’m sure it was meant to be “funny,” but I believe that anyone with any kind of sensitivity would see that this ad was in very poor taste.

—Marlboro Alum

(Potash Hill regrets that anyone was offended by this reprinted ad from the Citizen, which was indeed meant to be “funny,” and apologizes for being so insensitive. We hope that other readers will not hesitate to bring any concerns about the content and design of the magazine to our attention. —eds.)

Online Inclinations

I enjoy reading Potash Hill. I read it when it comes out as a PDF file online, then about four to eight weeks later I get a hard copy in the mail. I would like to make a small donation to Marlboro by requesting you stop sending me a hard copy.

—Anne Brooke ’73

(If there are others readers out there who would prefer to receive Potash Hill in a digital format only, especially those like Anne who are overseas, please let us know at pjohansson@marlboro.edu. —eds.)

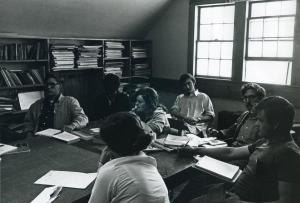

Thinking Against the Machine

By Meg Mott

Since Plato, political philosophers have taken on the responsibility of intellectual freedom. Politics professor Meg Mott explores how political philosophy and collective action combat the isolation of neoliberal economics.

Since Plato, political philosophers have taken on the responsibility of intellectual freedom. Politics professor Meg Mott explores how political philosophy and collective action combat the isolation of neoliberal economics.

The political theorist is committed to thinking outside the box or, as Plato might say, “thinking outside the cave.” Without this rigorous activity, the masses would remain shackled, forced to consume the same mind-numbing shadows produced by the regime. Without the intervention of the political theorist, the cave dwellers would understand politics to be a spectator sport. Only when the shackles come off do the cave dwellers start asking political questions, the first being, “What can we do about these ankle bracelets?”

Looking back across the millennia, it’s easy to see the value of political philosophers, especially during times when the cave was so stuffy. Most of us think of the Middle Ages as a time when church orthodoxy obliterated the marketplace of ideas—a time when political philosophy was really needed. But nowadays, with everyone on their mobile devices and contemplating their various options for where to dine out and whom to dine with, the need for political theorists seems less necessary. And yet, every era has its own particular cave, as invisible to its inhabitants as it is dismissed by succeeding generations.

The relatively new cave that political philosophers want us to notice is known as neoliberalism, an economic theory developed by Friedrich Hayek and then embraced by the University of Chicago School of Economics in the 1970s. Better known in this country as “Reaganomics,” neoliberalism operates under the assumption that markets make better decisions than government bureaucracies. Neoliberal leaders, such as Margaret Thatcher and Augusto Pinochet, privatized national industries and cut social services.

The effect on political culture was profound. With everything framed in terms of economic efficiencies, political values, such as deliberation and collaboration, bordered on extinction. Instead of practicing collective life, a society of individuals competed with each other for personal advantage.

Neoliberalism rewrote the metaphor of the cave: instead of looking at the same shadows on the wall, each cave dweller is fixated on their individual screen. At least in the ancient cave we might have rolled our collective eyes at the stupidity of the protagonist or found ourselves weeping in unison. Even the industrialized cave, described by Marx, provided the basis for a common experience. Once the workers saw how they were each alienated from their labor, they would rise up and demand better conditions in the cave. By making us think that our natural condition is separate, neoliberalism destroys the very possibility for collective action. Under neoliberalism, we aren’t just alienated from our labor. Rather, the I is alienated from the We.

Michel Foucault was one of the first political philosophers to raise the alarm about these new conditions. In a series of lectures in the late 1970s he spoke about a type of power that used “techniques oriented towards individuals and intended to rule them in a continuous and permanent way.” This “pastoral power” wasn’t an entirely new way of organizing the masses: Christian kings had used it successfully for centuries to guide their flock. However, when pastoral power was combined with market rationality the result was dangerously antipolitical. Where the medieval rulers moved the flock toward a shared and blessed future, the neoliberal rulers moved each member into total isolation.

Michel Foucault was one of the first political philosophers to raise the alarm about these new conditions. In a series of lectures in the late 1970s he spoke about a type of power that used “techniques oriented towards individuals and intended to rule them in a continuous and permanent way.” This “pastoral power” wasn’t an entirely new way of organizing the masses: Christian kings had used it successfully for centuries to guide their flock. However, when pastoral power was combined with market rationality the result was dangerously antipolitical. Where the medieval rulers moved the flock toward a shared and blessed future, the neoliberal rulers moved each member into total isolation.

Since Foucault’s time, the situation has become even more dire. According to contemporary political theorist Wendy Brown, entire “vocabularies, principles of justice, political cultures, habits of citizenship, practices of rules, and above all, democratic imaginaries” are slipping away. Political questions such as “What do we need to improve our neighborhoods?” have been displaced by “How can I get ahead?” With all aspects of existence described in individual terms, we can’t see ourselves as anything but isolated players in a highly competitive game. This is even true in higher education, argues Brown, where college administrators have abandoned political conceptions of life for the metrics of the marketplace.

Brown’s concerns are well founded. Under the Obama Administration, colleges and universities are required to report average student debt and expected earnings for their graduates. It makes sense, then, that college students would come to see themselves in purely economic terms. Who can afford to invest their time reading Plato or Foucault? The denizens of the neoliberal college do not have the leisure to think politically, but must figure out the cost and benefits of studying a particular major.

It would appear that we have become the very society that Foucault predicted would emerge under neoliberal policies. “We are at the civilizational turning point that neoliberal rationality marks,” concludes Brown, pointing to its deep antihumanism and surrender to a condition of human impotence. Normally, this would be a time when political philosophy flew in for the rescue, but with so few undergraduates investing their time in political theory, who will free us now? Has political philosophy finally met its match under neoliberalism?

While I share Foucault’s and Brown’s concerns, I’m too much a student of Aristotle to cede our natural political instincts. Even in this era of handheld devices and precarious economics, collective political action has not been erased. If anything, we’re seeing an upswing in democratic action, such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter. The individuals who participate in these social movements are not alienated from each other but are compelled to act together. They find themselves having to organize themselves and make collective decisions. The conditions of the neoliberal cave, like the conditions of Marx’s capitalist cave, provoke a social response.

Black Lives Matter, for example, has used the conditions of police violence against unarmed black persons to organize toward greater political action. By challenging police violence, Black Lives Matter threatens the most invidious quality of neoliberalism: the process of individualization, when each person is obsessed with his or her isolated screen. When everyone’s eyes are on the same disturbing event, the audience discovers its power. Earlier protests expressed outrage at what the state was doing, with calls like “No justice, no peace.” As the group realized its strength, the line shifted to Kendrick Lamar’s “We’re gonna be alright.” Like Marx’s proletariat, protestors began by focusing on what was being done to them and then began imagining what they could do for themselves.

If social movements respond to real world events, not to lectures delivered by erudite philosophers in refined auditoriums, why do we need political philosophy?

Political theory’s enduring contribution is its capacity to step out of an existing framework and offer a different set of values. As my dissertation advisor Nick Xenos recently said, political theorists do not study the Thing. We study the Thing behind the Thing. In other words, we study the Thing that runs the projector. Where social movements organize around the disturbing events on the screen, political theory asks, “What does police violence tell us about the crisis of capitalism?” We study patterns of control across centuries in order to assess the current manifestations. We study the past so that we can think beyond the syntax of the present.

Political theory becomes crucial when social movements are asked to speak to the larger public. This is particularly true of Occupy Wall Street, which is often dismissed for not having achieved any goals. Looked at from the rubric of neoliberalism, where success is defined as “meeting one’s objective,” OWS clearly failed. But explored under the values of democratic philosophy, where success means developing political habits and enlarging a group’s political imagination, OWS clearly succeeded.

Political theory becomes crucial when social movements are asked to speak to the larger public. This is particularly true of Occupy Wall Street, which is often dismissed for not having achieved any goals. Looked at from the rubric of neoliberalism, where success is defined as “meeting one’s objective,” OWS clearly failed. But explored under the values of democratic philosophy, where success means developing political habits and enlarging a group’s political imagination, OWS clearly succeeded.

Even with groups with clearly articulated goals, such as Black Lives Matter, social movements run the risk of winning battles and losing the war. If community policing is instituted in this country, it will need a different set of principles than were developed under neoliberalism. Most of the tough tactics used by police were developed with the support of black leaders in black neighborhoods that were being destroyed by drug use and crime. These community leaders, like all leaders operating in the cave known as the War on Drugs, believed what the screen told them to believe: that crime was the result of individual actions and personal choices. Black Lives Matter may reject those principles but they need other vocabularies and political imaginaries, to quote Wendy Brown, to explain those noneconomic principles.

In fact, many of the organizers of Black Lives Matter are doing what the organizers of the Civil Rights Movement did: they are developing political habits. They are meeting in church basements and role-playing encounters with the police, who are afraid of getting hurt; and homeowners, who are afraid of riot; and business owners, who are afraid of looting. Building on the lessons learned by Freedom Riders in the 1960s and AIDS activists in the 1980s and other nonviolent organizers who use creativity and imagination to resist the logic of the marketplace, organizers in Black Lives Matter are increasing our collective capacity for democratic action. And while the habits are themselves liberating, one still needs the political principles to anchor these habits outside the cave.

Political theorizing, a capacity we all share, reminds us that we can think beyond the logic of whatever rationality is keeping us shackled to the shadows of the day. Even the tightly ordered neoliberal cave, with its insistent demands for productivity and efficiency, will not keep us from our political natures. The world reliably gives us the conditions to be more than the sum of our individual anxieties. We just need to see ourselves as political actors: the sort of people who know that what they create is infinitely more interesting than anything being projected on the screen.

Meg Mott teaches political theory at Marlboro and is director of Speech Matters, a semester intensive that investigates a single issue through the many ways it is talked about (see Fall 2015 Potash Hill).

Up from Substance Use Prevention

“If you come in from a perspective of ‘this substance will only destroy your life’ you are creating an environment of shame—you are only keeping people further disconnected,” said sophomore Ariana Rodrigues-Juarbe, a student in Speech Matters last fall. She presented her final project, a ‘zine on how we talk about substance use in our society, at a public forum by eight students from the semester intensive at the Marlboro College Graduate Center in December. Ariana’s emphasis is on turning “prevention into comprehension,” or to take Meg’s metaphor one step further, to step outside the cave of “Just Say No.” “It all came together with the idea that if we want to actually address substance use, we have to understand that not everyone is coming from the same place, both in how they use, and in what that use means in their life,” said Ariana. See video excerpts from the public forum.

“If you come in from a perspective of ‘this substance will only destroy your life’ you are creating an environment of shame—you are only keeping people further disconnected,” said sophomore Ariana Rodrigues-Juarbe, a student in Speech Matters last fall. She presented her final project, a ‘zine on how we talk about substance use in our society, at a public forum by eight students from the semester intensive at the Marlboro College Graduate Center in December. Ariana’s emphasis is on turning “prevention into comprehension,” or to take Meg’s metaphor one step further, to step outside the cave of “Just Say No.” “It all came together with the idea that if we want to actually address substance use, we have to understand that not everyone is coming from the same place, both in how they use, and in what that use means in their life,” said Ariana. See video excerpts from the public forum.

Green Mountain Feminism

By Kelly Hickey

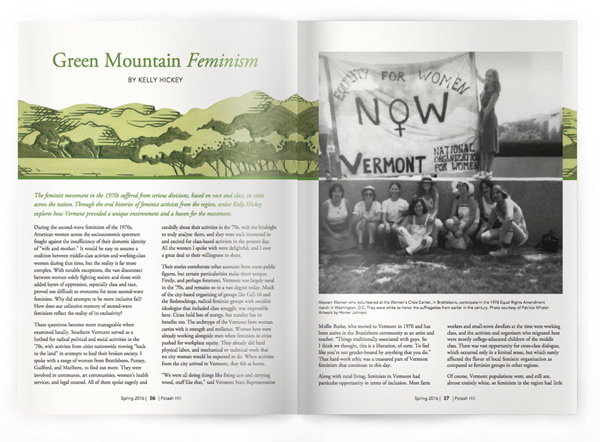

The feminist movement in the 1970s suffered from serious divisions, based on race and class, in cities across the nation. Through the oral histories of feminist activists from the region, senior Kelly Hickey explores how Vermont provided a unique environment and a haven for the movement.

During the second-wave feminism of the 1970s, American women across the socioeconomic spectrum fought against the insufficiency of their domestic identity of “wife and mother.” It would be easy to assume a coalition between middle-class activists and working-class women during that time, but the reality is far more complex. With notable exceptions, the vast disconnect between women solely fighting sexism and those with added layers of oppression, especially class and race, proved too difficult to overcome for most second-wave feminists. Why did attempts to be more inclusive fail? How does our collective memory of second-wave feminism reflect the reality of its exclusivity?

During the second-wave feminism of the 1970s, American women across the socioeconomic spectrum fought against the insufficiency of their domestic identity of “wife and mother.” It would be easy to assume a coalition between middle-class activists and working-class women during that time, but the reality is far more complex. With notable exceptions, the vast disconnect between women solely fighting sexism and those with added layers of oppression, especially class and race, proved too difficult to overcome for most second-wave feminists. Why did attempts to be more inclusive fail? How does our collective memory of second-wave feminism reflect the reality of its exclusivity?

These questions become more manageable when examined locally. Southern Vermont served as a hotbed for radical political and social activities in the ’70s, with activists from cities nationwide moving “back to the land” in attempts to heal their broken society. I spoke with a range of women from Brattleboro, Putney, Guilford, and Marlboro, to find out more. They were involved in communes, art communities, women’s health services, and legal counsel. All of them spoke eagerly and candidly about their activities in the ’70s, with the hindsight to truly analyze them, and they were each interested in and excited for class-based activism in the present day. All the women I spoke with were delightful, and I owe a great deal to their willingness to share.

Their stories corroborate other accounts from more-public figures, but certain particularities make them unique. Firstly, and perhaps foremost, Vermont was largely rural in the ’70s, and remains so to a vast degree today. Much of the city-based organizing of groups like Cell-16 and the Redstockings, radical feminist groups with socialist ideologies that included class struggle, was impossible here. Cities hold lots of energy, but rurality has its benefits too. The archetype of the Vermont farm woman carries with it strength and resilience. Women here were already working alongside men when feminists in cities pushed for workplace equity. They already did hard physical labor, and mechanical or technical work that no city woman would be expected to do. When activists from the city arrived in Vermont, they felt at home.

“We were all doing things like fixing cars and carrying wood, stuff like that,” said Vermont State Representative Mollie Burke, who moved to Vermont in 1970 and has been active in the Brattleboro community as an artist and teacher. “Things traditionally associated with guys. So I think we thought, this is a liberation, of sorts. To feel like you’re not gender-bound by anything that you do.” That hard-work ethic was a treasured part of Vermont feminism that continues to this day.

Along with rural living, feminists in Vermont had particular opportunity in terms of inclusion. Most farm workers and small-town dwellers at the time were working class, and the activists and organizers who migrated here were mostly college-educated children of the middle class. There was vast opportunity for cross-class dialogue, which occurred only in a limited sense, but which surely affected the flavor of local feminist organization as compared to feminist groups in other regions.

Of course, Vermont populations were, and still are, almost entirely white, so feminism in the region had little to deal with in terms of racial tension. The lack of racial diversity couldn’t be considered an asset to any burgeoning social movement, but it is a fact that influenced the way women’s liberation organizations were run. Instead of hearing directly from women of color, in many cases Vermont feminists had to sympathize from afar with situations quite removed from their daily lives. Isolation could be difficult in other ways, as women in rural Vermont had fewer interactions with other politically active women than did women living in, say, New York.

Feminist women in rural Vermont certainly lived a different existence than many city-based feminists in the ’70s. Those who could afford to attend conferences and trainings elsewhere, those who could spend time and money on higher education, and those in professional networks kept the rest of the women connected to feminist movements across the nation. In Vermont, as in other rural areas, the middle class served as the links in a network of poor or otherwise marginalized women.

Feminist women in rural Vermont certainly lived a different existence than many city-based feminists in the ’70s. Those who could afford to attend conferences and trainings elsewhere, those who could spend time and money on higher education, and those in professional networks kept the rest of the women connected to feminist movements across the nation. In Vermont, as in other rural areas, the middle class served as the links in a network of poor or otherwise marginalized women.

Certain issues in particular did ignite cross-class coalition among women. One of the most serious and significant of these was violence against women. The Women’s Crisis Center in Brattleboro, and presumably other women’s health clinics around the country, provided safe space for women to talk about their abuse, their fears, and their needs. Women realized that domestic violence was an issue for all of them, regardless of background.

The Honorable Patricia Whalen is a local judge who founded the Rural Women Leadership Institute of Vermont and served on the International Criminal Tribunal for Bosnia. In the ’70s, Patti worked at the Women’s Crisis Center, which she helped found, providing legal aid to low-income women. She described one incident where a wealthy woman with beautiful clothes came to the center, and the other women resented her right away. She was very attractive and had no outward signs of being beaten like the others.

“She said, ‘Yeah, you’re right. My husband would never do that to me, because he would never want the public to see that he hit me,’” recounted Patti. “And then she just pushed her sleeve up, and she said, ‘No, he just put his cigarettes out on me all the time.’ She was just horribly burned and scarred. And the women were like, ‘Holy crap, my husband never did that to me. Wait a minute, that’s, like, really bad.’ And so there was always common ground found in stuff.”

As these crisis centers started to use consciousness-raising circles as healing spaces for women, more cross-class interactions and sympathies became possible. Violence against women is more prevalent in lower economic brackets, and working-class women also tend to need more legal assistance and time in shelters after leaving abusive partners. But while most of the long-term clients of the crisis center were working-class women, middle-class and wealthy women who visited the clinic for shorter-term support were able to participate in an open and honest cross-class dialogue.

Abortion rights groups and advocates of accessible birth control options also managed to initiate dialogue across class lines, as unwanted pregnancy and family planning are issues with which all sorts of women can identify.

In the end, however, working-class women still didn’t have even close to the options of their middle-class sisters. Mollie Burke experienced the radical ’70s as more of a personal evolution than a group consciousness-raising. Her story of working in a male-dominated, blue-collar environment epitomizes the difference between working-class women and the educated middle class, even in Vermont.

“I worked as a waitress, briefly. I was a terrible waitress,” said Mollie, laughing. “There were other women who worked at this restaurant, that no longer exists, and one woman had six children. And the kid, who was the son of the owner, would boss these women around, and call them ‘girls.’ I mean, it was horrible. But I could get out, you know. They needed to stay.” And truly, education was the pith of it. Many of these activists had no more money than the women they worked alongside and for, but they had the family and educational safety nets to change course when necessary.

In her work at the Women’s Crisis Center and in the region, Patti Whalen has had an intimate perspective on the divergence between poor women and middle-class feminists. She described a shift in consciousness of the middle-class volunteers at the center, from collaborating with low-income feminists to fighting for their own issues.

In her work at the Women’s Crisis Center and in the region, Patti Whalen has had an intimate perspective on the divergence between poor women and middle-class feminists. She described a shift in consciousness of the middle-class volunteers at the center, from collaborating with low-income feminists to fighting for their own issues.

“I think everybody understood, in a way, that we were going to get a seat at the table,” said Patti. “And then when we got a seat at the table, we were all of a sudden going to chair the table.”

The activists who flocked to Vermont to eschew society in the early ’70s realized their potential power—as members of that very same structure. Patti went on to name women she worked with, women who moved on to run nonprofit organizations, who serve in the legislature, who work for other leading activists and politicians. The welfare fight wasn’t being won, and middle-class feminists developed other priorities. They turned to the Equal Rights Amendment with full force, and the failure to ratify that bill stymied any further momentum across classes.

International women’s rights movements began to pick up at the end of the decade, with more frequent UN conferences and greater popular awareness of rights violations around the world. Issues like child brides and female genital mutilation were easy to oppose for American women across class lines. Yet even in Vermont, which had its unique chapter in the history of feminism, it seems this international outreach has done little to unite women across classes on national feminist issues.

Kelly Hickey is a senior at Marlboro working on a Plan of Concentration in oral history and visual arts. This article is excerpted from a paper that is a work in progress toward Kelly’s Plan, originally written for the Politics of Change class.

Radicals in These Hills

Kelly and other Marlboro students presented their oral history projects in a public event at the Campus Center in December, titled “Radicals in These Hills,” the culmination of their course Politics of Change: Radical Movements of the Late 20th Century. Taught by theater professor Brenda Foley and American studies professor Kate Ratcliff, the class was part of a pilot for a far-reaching collaborative project produced by Vermont Performance Lab (VPL), in partnership with Green Mountain Crossroads (GMC) and the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project. This partnership is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Samara Fund of the Vermont Community Foundation. VPL theater artist Ain Gordon and HB Lozito of GMC co-directed the class, and many of the oral histories were made possible by VPL’s connections to the local community. “The class is part of a larger vision for a Center for Performing Arts and Social Practice that links coursework and community engagement with VPL artists’ research,” says Sara Coffey ’90, VPL founder and director. “One of the many things we hope to create is an archive on local radical movements, a resource for the broader community that will include students’ work, oral histories, and archival materials.” See a video of the whole event.

Small Town Pride

“The Andrews Inn appears to be Vermont’s answer to the Stonewall Inn, a haven for LGBTQ people to be out and proud, to socialize, be free, have sex,” says senior Rainbow Stakiwicz (pictured with interviewee Eva Mondon), a student in last fall’s Politics of Change class. She did her oral history project on the Bellows Falls gay bar, which thrived through “the long 1970s” until closing in 1982 under mysterious circumstances. “It lives in legend and lore, but its life is largely undocumented, considering that it was well known all along the East Coast.” With the help of Robert McBride of the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project and Vermont Performance Lab, Rainbow was able to speak to some of the patrons who are still around. They remember the inn with fondness as a place where they could express themselves at a time when, in most places, they could not. Her project culminated in a short piece of theater based on her findings. See a video of a reading.

War Talk

By Jay Craven

Like all Americans, I was shocked by the recent ISIS attacks in Paris, Beirut, Mali, and Egypt, and by mass shootings in Colorado Springs and San Bernardino. Some presidential candidates insist this is the start of World War III—and urge an all-out response.

Like all Americans, I was shocked by the recent ISIS attacks in Paris, Beirut, Mali, and Egypt, and by mass shootings in Colorado Springs and San Bernardino. Some presidential candidates insist this is the start of World War III—and urge an all-out response.

While I understand the sentiment to rush to war, we shouldn’t forget that World War I laid the groundwork for the cataclysm of World War II. Our own Iraq War created conditions that still fuel conflict today. And gun violence right here at home has claimed 406,000 lives since 9/11—far more than terrorism and war.

Just days after 9/11, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist David Halberstam attended an urgent meeting of current and former U.S. intelligence officials who insisted upon two things. “Do not do what they want you to do,” they warned. “Do not go to war.” Second, they urged leaders to “dry up the swamp” through constructive engagement, to peel away from insurgents people of aspiration and good will, to show alternatives to people plagued by decades of war, poverty, illiteracy, and suppression of women, progressives, and minorities.

Leaders say that moderate Muslims are the key to peace. And if that’s true, we must find ways to actually support this group, to show that wealthy nations are prepared to invest substantially in social and economic progress as an alternative to war.

When I had a lunch meeting with historian Howard Zinn just weeks before he died in 2010, he recalled lessons he’d learned as a decorated World War II bombing pilot over France, lessons that led him to oppose war. He lamented the 85 million people who were killed by 20th-century wars, the more recent spread of war, foreign intervention and occupation, nuclear proliferation, and terrorism—including domestic bombings and mass shootings.

“The only solution,” Zinn said, “is to abolish war, to mount a call equal to the movement to abolish slavery. The enemy is not a group or nation; the enemy is militarism itself.”

President Kennedy made a similar point in his historic speech at American University when he argued against a peace “enforced on the world by American weapons of war.” He spoke instead of “the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living...not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women, not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.”

I hope we can embrace this challenge to quell violence through imagination, not force. I have to believe it’s not too late.

Jay Craven is professor of film and video studies and director of Movies from Marlboro, the semester intensive program that is spending spring 2016 filming Wetware, a noir thriller based on the novel by Craig Nova. This editorial was delivered on VPR on December 9, 2015.

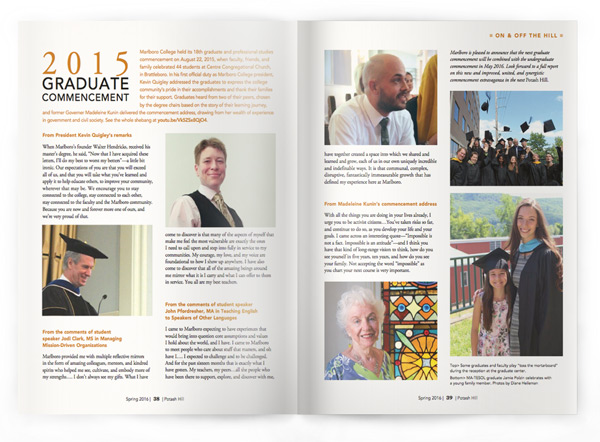

On & Off the Hill

Still Worldly After All These Years, Dana Howell Retires

“The most powerful attraction of all was the freedom of the place,” says Dana Howell, referring to what first brought her to Marlboro in 1985. “Teaching and learning actually became part of the same process. It was a job and a place where you could grow. That was catnip.” After 30 years of growing and teaching cultural history at Marlboro, Dana retires this year.

“The most powerful attraction of all was the freedom of the place,” says Dana Howell, referring to what first brought her to Marlboro in 1985. “Teaching and learning actually became part of the same process. It was a job and a place where you could grow. That was catnip.” After 30 years of growing and teaching cultural history at Marlboro, Dana retires this year.

Dana first came to Marlboro as the single designated faculty member for the World Studies Program (WSP), the innovative international studies program in partnership with the School for International Training. She taught on both campuses, as well as working on admissions, marketing, curriculum, and administration for WSP, and was so effective she was appointed director of the program, a position she served in for five years.

“The first World Studies Program students were both test pilots and co-pilots; they helped establish an unusual program that worked for students in any field,” says Dana. “We had students on all continents, and in fields from literature to environmental studies to dance. They did their six months of working internships abroad without cell phones or email—hard to imagine now.”

“Dana’s rigorous and creative approach to thinking about culture, history, and performance influenced me so deeply,” says Sara Coffey ’90, founder and director of Vermont Performance Lab. One of the first students in the World Studies Program, Sara completed 10 months of study, research, and dancing in Bali, Indonesia. “As a folklorist, Dana taught me new ways of looking at performance and culture, and since then I have never stopped being fascinated by how performance is embedded with meaning and reflects cultural and societal values.”

“Dana found my Plan topic as interesting as I did,” says Anne Carmichael Ledvina ’90, associate director of international programs at Birmingham-Southern College. “I will never be able to express the impact she has had on my life and the ‘untrodden’ path I have chosen. She is a nurturer of idealists.” Dana particularly enjoyed co-teaching. Her first courses at Marlboro were co-taught with Tim Little, whom she later married, and she always appreciated finding new connections between disciplines.

“Dana gave me the chance to see and experience what real interdisciplinarity is,” says art history professor Felicity Ratt., who collaborated with Dana on several occasions, including a course last fall called A History of Now. “Working with her, our two disciplines were not separate methodologies examining an issue together, but a complex intermixing and intermingling of methods that created a whole new set of insights into material. I admire the sheer pleasure Dana demonstrates in complex thought.”

Retired theater professor Paul Nelsen also co-taught courses and co-sponsored Plans with Dana. He says, “Students loved the animated discourse with Dana, the dialectical grappling with big ideas in classes and tutorials. She deeply attached herself to the core idealism of Marlboro and was an inspirational force behind outstanding work of many students.”

Retired theater professor Paul Nelsen also co-taught courses and co-sponsored Plans with Dana. He says, “Students loved the animated discourse with Dana, the dialectical grappling with big ideas in classes and tutorials. She deeply attached herself to the core idealism of Marlboro and was an inspirational force behind outstanding work of many students.”

Literature professor Geraldine Pittman de Battle says, “Sharing Plans with Dana has meant that I have learned, and been excited by, her knowledge and her imagination. Marlboro is a hard place to get to know, but she knew immediately what a wonderful place it was and spent her entire career here keeping the ideals of Marlboro in countless ways.”

“Working with Dana was a privilege and a pivotal part of my undergraduate education,” says Colby Silver ’12, now in graduate school for international affairs at The New School. “The extent of her knowledge in a wide breadth of topics was always inspiring, and reinforced the value of a self-directed liberal arts education.”

“The thing that drew me to Dana, and the thing I admired most about her, was her way of interacting with her students,” says Amy Frazier ’06, now the film and media librarian at Middlebury College. “She’s plainspoken; you always knew that she’d tell you what she really thought. I know I presented her with some teaching challenges back in my day, but I wouldn’t be the person I am without her influence.”

“I’m always surprised by the creativity of students here, and the diversity in this small community,” says Dana, whose international perspective and wide-ranging interests allowed her to work with Plan students on a broad range of topics, from seafaring in Newfoundland to Japanese fashion. “I never know what to expect—they always think of something I haven’t. I have valued the intelligence, independent-mindedness, and irreverent humor of students at Marlboro. I will miss that.”

“Both in class, as well as in the roles of Plan sponsor and friend, Dana has displayed an innovative and inquisitive rigor that I find exhilarating and instrumental,” says one former student, now a graduate student in humanities at University of Chicago. “I continue to reap the benefits of having explored difficult lines of inquiry with her. I very much admire her ability to bring to light increasingly complex networks of cultural connections in contemporary events and thought.”

“I have always been in awe of Dana’s ability to bring together widely disparate ideas in a coherent and meaningful way,” says Kimberly Mills ’89, who went on to get her doctorate and teach anthropology for 10 years. “Dana gave me permission to be myself in the academic world. Her willingness to accept my ideas as both valid and valuable built my confidence as a scholar, and as a person, in ways that no one else has ever matched.”

Starting in 2000, Dana worked with the Open Society Institute (OSI), the international grant-making network now called Open Society Foundations. She led an evaluation team to the first liberal arts college in Russia, then served as chair of an international academic advisory committee. In that capacity she selected and supported projects for democratizing undergraduate teaching in the post-Soviet region, traveling each summer to projects from Kyrgyzstan to Croatia.

“Dana’s passion for teaching captured me, and remains something, I am convinced, that few can do so well,” says Rhett Bowlin ’93, who directed OSI’s International Higher Education Support program for nine years and recruited Dana to work with him. “With Dana I realized that I was empowered to make all kinds of consequentially positive choices in my life, for the rest of my life, including my choice to ask her to work with me.”

Will Jenkins ’10, who’s working on a doctoral dissertation in history at UC Berkeley, says, “Dana makes education an extended conversation. I genuinely think of my Plan as a product of our conversations over the course of two years, and even casual conversations we had in tutorials have been foundational to my academic trajectory since then. I’ve never met anyone since who treats both her subject and her students with such respect.”

Will Jenkins ’10, who’s working on a doctoral dissertation in history at UC Berkeley, says, “Dana makes education an extended conversation. I genuinely think of my Plan as a product of our conversations over the course of two years, and even casual conversations we had in tutorials have been foundational to my academic trajectory since then. I’ve never met anyone since who treats both her subject and her students with such respect.”

Dana’s plans for retirement are open. Her book The Development of Soviet Folkloristics was reissued last year by Routledge, and she plans to do some more writing. She has the usual list of “finally time for” things, like traveling to Patagonia, learning ancient Greek, and reading War and Peace in Russian.

“For several years, I’ve been focused on the normalization of war, the various presences of war in society, and the extension of war to civilians. So I am most absorbed by that at present. I don’t know how ambitious I’ll be, but I know I won’t be bored.”

Marlboro Marks ADA Anniversary

Marlboro College celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act with a series of events during the first week of November. These included film screenings, talks, and discussions, as well as a campus-wide action on November 5 where community members spent a full day using walkers, wheelchairs, and other assistive devices.

Marlboro College celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act with a series of events during the first week of November. These included film screenings, talks, and discussions, as well as a campus-wide action on November 5 where community members spent a full day using walkers, wheelchairs, and other assistive devices.

“As a faculty member with a disability who is also a professional actress and writer, I embrace the anniversary of the ADA as a timely reminder of the need to create more opportunities for people with disabilities,” says Brenda Foley, Marlboro theater and gender studies professor. “A committee composed of staff, students, and faculty, including those with multiple and varied disabilities, organized the celebration as a way to encourage awareness of—and support for—the diverse range of disabilities in our community.”

“Our goal was to heighten awareness and educate our community about the ADA legislation, and to inspire us to continue the struggles,” says Catherine O’Callahan, assistant dean of academic advising and support, who convened the committee.

The week of events was initiated by disability rights advocate Sarah Launderville (Vermont Council on Independent Living), who led a community-wide “dedicated hour” discussion addressing the complexity of the concept of “limitation.” Later in the week, Deborah Lisi-Baker (Center on Disability and Community Inclusion, University of Vermont) articulated the need for an expansive pedagogy at the college to address all disabilities, from learning to mobility.

There were screenings of Lives Worth Living, a PBS documentary on the disability rights movement, and Disability Liberated, a work by the performance artist group Sins Invalid on disability and prisons. But perhaps the most visible component was the assistive device activity, which occurred in the broader context of the week’s discussions of awareness, assumptions, and advocacy. “

As someone who uses multiple assistive devices every day on our rural campus terrain, I was gratified by the thoughtful consideration and participation of so many of our community members,” says Brenda. “All who participated submitted responses addressing their experience, and we held a roundtable discussion to further frame their participation in the larger context of inclusion and discrimination.”

“I understood that being in the wheelchair all day would be a physical challenge,” says senior Rainbow Stakiwicz, one of 40 participants on campus and at the graduate center who adopted an assistive device for the day. “What I wasn’t expecting was how emotional it would be. I felt detached, tired, strange, and far away from everything. But while I think I learned a lot, and gained a new perspective and way of seeing, I would never presume to know what life is like for a disabled person.”

“Who knew that such a little two-inch square of black patch could undermine my whole sense of self?” says politics professor Lynette Rummel, who chose visual impairment for her disability. Others approximated hearing impairment with earplugs. “The lessons learned will remain with me for a lifetime, of that I am sure.”

Additionally, senior staff, members of the Standing Building Committee, and the event committee held a lunch discussion on curricular initiatives on campus that cross disciplines, as well as on crafting a plan for ADA compliance and accessibility. An ad hoc committee has been designated to complete an accessibility audit of the campus this year, and has been hard at work.

“We have been using an ADA checklist to guide us as we methodically assess each building: clipboards, tape measures, carpenter’s level, door pressure gauge, and cameras in hand,” says Catherine. “By the end of the spring term we will have a report to the community— then the hard work of prioritizing needs will begin.”

“The expansive and collaborative nature of this event, and the thoughtful responses from community members, is indicative of our shared commitment to disability advocacy and activism in the Marlboro community,” says Brenda.

Roberto Lugo Builds Community with Clay

“The sort of questions that Marlboro students ask are aligned with the questions that I ask,” says Roberto Lugo, who joined Marlboro as the ceramics professor last fall. “People here just have a tendency to question everything, which is really refreshing. I would get bored just teaching people how to be technically virtuous potters. I’m more interested in how pottery relates to biology, how pottery relates to anthropology, and all these other ways that people here really question.”

“The sort of questions that Marlboro students ask are aligned with the questions that I ask,” says Roberto Lugo, who joined Marlboro as the ceramics professor last fall. “People here just have a tendency to question everything, which is really refreshing. I would get bored just teaching people how to be technically virtuous potters. I’m more interested in how pottery relates to biology, how pottery relates to anthropology, and all these other ways that people here really question.”

Rob didn’t always know he would be a ceramic artist. Growing up in West Philadelphia, he had a flair for painting graffiti art on abandoned buildings, but he recognized that the only way to be economically successful in that environment was selling drugs. When he realized that too many among his family and friends had suffered from violence or imprisonment due to their involvement in the drug trade, he left the city to live with a cousin in Florida. He started ceramics at a community college there, at the age of 25, and has never looked back. He received his bachelor’s in ceramics from Kansas City Art Institute and an MFA from Pennsylvania State University.

Marlboro is very different from the academic environments Rob had experienced in the past, not to mention the most rural environment in which he has found himself (he relished eating his first apple straight from a tree this fall, for example). What drew him to the college, as is the case for many faculty, was the close-knit community and students’ sense of engagement in their own self-designed course of study.

“I liked that Marlboro has a curriculum that sort of creates itself based on the interests of the students,” says Rob. “I knew if I wanted to walk on new terrain, and think about ways that clay hasn’t been used before, I would really have to be grounded by people who are doing similar things with their own interests. Since I got here I feel like I’m discovering something new every day.”

Rob sees ceramics classes as a unique environment for bringing people together as a community. His introductory class last fall included everyone from freshmen to local community members, including retired economics professor Jim Tober, and he liked creating an environment in which they could learn from each other. He’s found Marlboro to be unique, in his experience, in the level of openness and encouragement that students share with each other.

“With artwork, the conversation will be around communicating your idea rather than whether your idea is valid or not,” he says. “That’s what I like about it, because a person is welcome to express themself in whatever way they wish, and our jobs, as we critique the work, is to let that person know whether they are doing it effectively.”

“With artwork, the conversation will be around communicating your idea rather than whether your idea is valid or not,” he says. “That’s what I like about it, because a person is welcome to express themself in whatever way they wish, and our jobs, as we critique the work, is to let that person know whether they are doing it effectively.”

Rob’s own work juxtaposes images from popular culture, European decorative patterning, and rich symbolism drawn from his Puerto Rican heritage, creating a hybrid of visual arts traditions that stimulates new conversations surrounding cultural tolerance. His designs have ranged from combining graffiti and fine china to putting Nobel Prize laureate and Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai and cartoon character Fat Albert on the same pot.

“It kind of gets people questioning what they hold dear about design,” says Rob. “Are you attached to the aristocratic component of it? Or are you willing to see where both of our needs, and both of our ideas, intersect? I like challenging people in that way.”

Rob believes that his physical work gains strength from his other work as an activist, doing public speaking and making videos that address poverty, prejudice, and injustice. In one video, he returned to Philadelphia, to a block of burned-out houses with “stairways going to nowhere,” where he assembled a pottery wheel out of discarded objects and threw a pot from clay reclaimed on site. His impassioned speech at the 2015 NCECA (National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts) conference, where he was presented with an emerging artist award, has gained him national recognition.

“I think that sort of multimodal practice really lends itself to the Marlboro community,” Rob says. He is collaborating with economics professor John Rush on a project in Puerto Rico, where faculty and students will help introduce a sustainable pottery workshop to bring revenue to a disadvantaged community. He looks forward to collaborating with other professors as well, in areas of study from anthropology to performance art. One thing that remains to be seen is how Rob’s art will change from his experiences at Marlboro.

“My work has a close relationship with my experience as a human, and has always included a discussion of what it means to be a person of color from a really poor neighborhood,” says Rob. “Now I’m a professor, and I’m in Vermont, so what does that mean for my work? Am I going to draw a moose on my pots? Because I think that would actually look really cool.”

Nelli Sargsyan Pursues Empathy through Anthropology

Anthropology professor Nelli Sargsyan, who also joined the faculty in the fall, was drawn to Marlboro because of its close-knit and egalitarian community, in which she appreciates “the horizontality of structure.” She was impressed that there were engaged students on the search committee that interviewed her, and that people really know each other and make decisions together. Coming from a larger school, she also likes that Marlboro is still focusing on the liberal arts, not on vocational training.

“Marlboro allows space for exploring and thinking, which I really appreciate,” Nelli says. “The classes are small enough that you can engage in meaningful discussions with the students, and they have the freedom to go in directions that interest them.” She feels very aligned with the way writing and critical thinking are so crucial to Marlboro’s academic approach, and with the multidisciplinary nature of the learning environment.

“Here I am limited only by my imagination, in terms of the classes that I could teach, which is both overwhelming and really exciting,” she says. “It seems like Marlboro allows thinking across disciplines to happen very organically, among colleagues and also in response to students’ interests.” This semester she is teaching a course with photography professor John Willis that incorporates visual anthropology and social justice issues, and she looks forward to collaborating with other faculty across disciplines.

Originally from Armenia, Nelli received her bachelor’s degree from Yerevan State Institute of Foreign Languages, then her master’s and doctoral degrees in anthropology from State University of New York at Albany. She has taught in diverse college settings, from Yerevan State Linguistic University, in Armenia, to SUNY Albany, but she has never encountered the concentration of critically thinking students that she finds at Marlboro.

“It seems like the students who come to Marlboro are interested in posing the kinds of questions that I am interested in as well, re-examining certain social institutions or understandings of concepts and how these things operate in our lives. So that’s very exciting for me. I want students to be demanding of me, to make me do more intellectual work, question things, and push in directions that I haven’t explored, that we can engage in together.”

To Nelli, the goal of her classes at Marlboro is to help students think as anthropologists, with an awareness of our shared humanity and sensitivity to how lives and experiences are situated.

“Thinking like an anthropologist is being aware of this common humanity that we all have, of the fact that we share much more despite our differences. At the same time, it is being aware that these differences contribute to the flavor, the music, the color, and the texture of the human experience that one has. I think an anthropological way of knowing allows you to learn a lot about yourself, and about things that have informed your own way of living. This, then, makes it possible to listen more compassionately to many human stories, of which yours is just one.”

Nelli approaches teaching as an opportunity for cultivating social agency, the human capacity to make decisions and act on them, by engaging students in process-based and active learning experiences. One of the ways her students do this is by developing self-awareness and reflexivity, locating themselves in their own research.

“It’s about being aware that our own perspectives are always informed by the experiences that we’ve gone through, and are going through, that everything is tied to one’s own story. Creating an environment of empathy, in our little learning community of a classroom, gives the space where agency becomes possible outside the classroom as well.”

As far as her own research, Nelli’s doctoral work examined how Armenian-identified individuals negotiate their gender, ethnic, and sexual difference in the U.S. and in Armenia. Her dissertation resulted in a number of conference papers and publications, including a chapter in the book Creoles, Diasporas and Cosmopolitanisms: The Creolization of Nations, Cultural Migrations, Global Languages and Literature.

“I was interested in what it means to be Armenian for people who live in the U.S. diaspora, and how people navigate what it means to be Armenian of a certain gender, of a certain sexuality, of a certain race and religion. I was also interested in queer art-activism in Armenia, and as a result now I’m more interested in social movements in general.” Nelli looks forward to collaborating with Marlboro students on a field research project in this area.

Nelli considers Marlboro the perfect size, in terms of a functional community. When she visited the studio of ceramics professor Roberto Lugo, to make a bowl for the Empty Bowls Benefit Dinner, it occurred to her that her daughter’s elementary school class could help decorate some of the bowls. Rob said, “Yeah, sure.” Nelli talked to her daughter’s teacher, and, a week after Rob’s “Yeah, sure,” the primary class of Marlboro Elementary School was there in the studio, enriching the college campus with their energy and ensuring the bowl-making effort’s success.

“Just the ease with which things like that can happen is very significant to me,” says Nelli. “So besides the meaningful interdisciplinary collaborations, on a community level there’s this gentleness and connection that I appreciate.”

Also of Note

“I am fascinated by the algebraic structures on elliptic curves, especially elliptic curves defined over fields of finite characteristics,” says Ziyue “Zoey” Guo (pictured right), and there are few who could argue with her. Marlboro’s mathematics fellow for the academic year, Zoey completed her doctorate in mathematics in 2015, at Northwestern University, with a dissertation on Abelian graphs. “In particular, I look at the behavior in the Perron-Frobenius eigenvalues when a finite graph is expanded by adjoining two-valent trees.” She also enjoys playing the piano and viola, as well as rock climbing.

“I write short, weird fiction mostly, and I am planning a sci-fi novel but that is in a very preliminary stage,” says junior Derek Tollefson. He is also co-editor-in-chief of a remarkable literary journal called Milkfist, which came out with its debut issue in September 2015. Billed as “a compendium of art and writing for stammering low-lifes who barely know what year it is,” the magazine features work from both established and up-and-coming talents from all over the world.” Go to milkfist.com.

“I hold a special place in my heart for Arabic, as a poetic and beautiful language,” says Marwa Abayed, Marlboro’s Fulbright fellow in Arabic this year, who comes to us from Tunisia. “I believe it has been burdened with the most wrongful image as the language of ‘terrorists’ in the media.” Marwa has an undergraduate degree in English language, civilization, and literature, and has pursued graduate work in cultural studies and translations. She has been an active participant in the community, including performing in the recent production of The Language Archive.

“Kathy Urffer (pictured right) is the heartbeat of the grad school. Her title is registrar, but she is the driving force behind just about everything that happens here.” So says the entry nominating Kathy to win the first ever Staff Distinguished Service Award. The award is designed to honor Marlboro staff members for their contributions to the lives of one another and in service of the college’s mission. Among other things, Kathy was cited for organizing a group of staff to attend the Vermont Women in Higher Education conference last year.

Last year, senior Colin Leon joined his cousin Gray Davidson and a team of other sculptors to construct The Dancing Serpent, a 14-foot-long sculptural metal mobile inspired by some of the kinetic sculptures Colin included in his Plan show. The serpent-mobile was built to exhibit at Burning Man 2015, the annual festival of counterculture and pyrotechnics in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, where it gained many admirers. “Gray received a small grant from Burning Man to complete the piece and was in charge of the aesthetic decisions and the organization of the project,” said Colin. “I was his engineer, consultant, and ‘chief’ welder.” See the sculpture.

“I have become accustomed to using a wide variety of language-learning resources, and to tailoring teaching strategies to suit individual learning styles,” says Ella Grunberger-Kirsh, this year’s Oxford Classics Fellow. Ella earned her master’s in classics from Exeter College with a dissertation on “Cultural politics and poetic voice in the work of Ausonius of Bordeaux,” which won Oxford’s top classics research prize. She has won several other awards and scholarships for her work, and is founder of the Oxford University Classics Society.

Mountain Mystery

New students Sam Bunker ’18 and Merritt Meehan ’18 investigated a mysterious clue during the Bridges orientation trip titled Haunted Treasure Hunt 2K15. Photo by Connor Lancaster ’16

Calling All Scholars

Marlboro gained national attention when National Public Radio’s Amy Scott did a story on the college’s Renaissance Scholars Program.

Circle Up

Students, faculty, and staff shared their ideas for Marlboro’s future during a “meet the trustees” event in November.

Gift Horse

Students made a casting of a horse’s head from the pediment of the Parthenon in a workshop taught by sculpture professor Tim Segar, using a mold made by sculptor William Tucker.

Gimme Shelter

Carpenters Don Caponcelli and Brent Johnson close in the roof of the new gazebo near the center of campus.

Events

1 In October, Chicago-based dance theater group Lucky Plush performed The Queue, which takes place in a fictional airport where travelers stumble into each other’s private lives. 2 In November, Emerson College professor Yasser Munif investigated root causes of the Syrian refugee crisis. 3 Multi-instrumentalist Marty Ehrlich was joined by Marlboro faculty member Matan Rubinstien for a concert of original and improvised music in November. 4 In December, Dances in the Rough included Orchard, a work-in-progress stemming from research and interviews at Green Mountain Orchard in Putney, Vermont. 5 Sophomores Erin Huang-Schaffer and Amelia Fanelli explore the wonders of Esperanto in The Language Archive, directed by theater professor Jean O’Hara. 6 A butterfly by senior Megan Stypulkoski was one of countless works of art exhibited during open studios in December. 7 Junior John Marinelli and sophomore Allison Power strike a pose at the annual Hogwarts Dinner in October.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

Sophomore Noah Strauss Jenkins went on a stroll with philosophy professor William Edelglass to discuss classes, research projects, life with twin toddlers, and what is so phenomenal about phenomenology. You can read the whole interview.

Sophomore Noah Strauss Jenkins went on a stroll with philosophy professor William Edelglass to discuss classes, research projects, life with twin toddlers, and what is so phenomenal about phenomenology. You can read the whole interview.

Noah Straus Jenkins: So I’m wondering how you’ve seen this semester going?

William Edelglass: Phenomenology is a course I’ve been teaching this semester that I really love. I am inspired by the material, and it’s quite challenging for students. Many of the texts are often taught at the graduate level. I think they are profound, and the students are wonderful.

NSJ: I guess the natural question would be: what is phenomenology?

WE: Phaino in Greek means “to seem” or “appear.” Phenomenology isn’t really a Greek word, but one way of defining it would be to say that it is the study of that which appears. What that means is that it is an approach to thinking about, well, just about anything that begins with the first-person experience of whatever it is we’re talking about. So what does it mean, as opposed to what it is objectively.

NSJ: Okay, I see.

WE: So for example you and I are now walking up this driveway. There are all kinds of ways we could think about this driveway right now: you could look at the chemical elements, you could look at how deep the sand and gravel foundation goes, you could look at the incline, you could look at the trees on the sides.

NSJ: So how is phenomenology different?

WE: A phenomenological approach might be to start with, well, what does it feel like right now to be walking up, and mainly, what is the meaning of it to me? Phenomenology tries to provide an account of the structures and meanings at the foundation of our experience.

Focus on Faculty

Spanish language and literature professor Rosario de Swanson became the vice-chair of the Heritage Languages Interest Group, part of ACTFL (American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages). “Our group organizes panel discussions on research, maintenance, and promotion of heritage languages, defined as languages other than the dominant language in a given social context,” she says. Last March, Rosario presented a paper on Mexican writer Guadalupe Angeles at the Conference of Contemporary Mexican Literature at University of Texas, El Paso. She also traveled to Mexico last summer to interview painter Toni Guerra for a paper that is in the works.

MBA faculty member Cary Gaunt was recently named Keene State College’s new director of campus sustainability, based on her extensive expertise in stakeholder engagement and rich academic experience that includes Marlboro College. “It provides me the opportunity to work with faculty on curriculum development, the facilities department on sustainable building and infrastructure, students in a variety of capacities, and the broader Keene community and region.”