Restoring Kona Forests

by Robert Cabin ’89

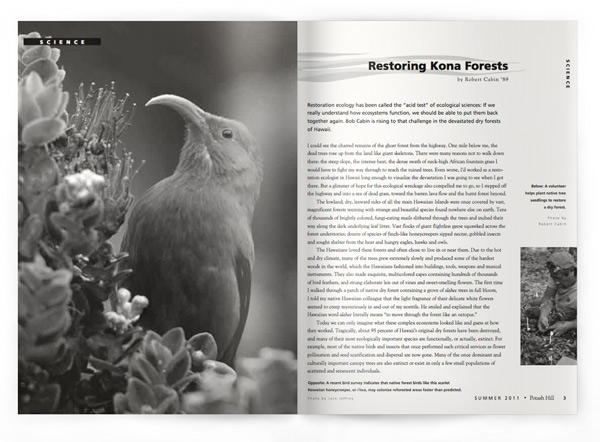

Restoration ecology has been called the “acid test” of ecological sciences: If we really understand how ecosystems function, we should be able to put them back together again. Bob Cabin is rising to that challenge in the devastated dry forests of Hawaii.

I could see the charred remains of the ghost forest from the highway. One mile below me, the dead trees rose up from the land like giant skeletons. There were many reasons not to walk down there: the steep slope, the intense heat, the dense swath of neck-high African fountain grass I would have to fight my way through to reach the ruined trees. Even worse, I’d worked as a restoration ecologist in Hawaii long enough to visualize the devastation I was going to see when I got there. But a glimmer of hope for this ecological wreckage also compelled me to go, so I stepped off the highway and into a sea of dead grass, toward the barren lava flow and the burnt forest beyond.

The lowland, dry, leeward sides of all the main Hawaiian Islands were once covered by vast, magnificent forests teeming with strange and beautiful species found nowhere else on earth. Tens of thousands of brightly colored, fungi-eating snails slithered through the trees and inched their way along the dark underlying leaf litter. Vast flocks of giant flightless geese squawked across the forest understories; dozens of species of finch-like honeycreepers sipped nectar, gobbled insects and sought shelter from the heat and hungry eagles, hawks and owls.

The Hawaiians loved these forests and often chose to live in or near them. Due to the hot and dry climate, many of the trees grew extremely slowly and produced some of the hardest woods in the world, which the Hawaiians fashioned into buildings, tools, weapons and musical instruments. They also made exquisite, multicolored capes containing hundreds of thousands of bird feathers, and strung elaborate leis out of vines and sweet-smelling flowers. The first time I walked through a patch of native dry forest containing a grove of alahee trees in full bloom, I told my native Hawaiian colleague that the light fragrance of their delicate white flowers seemed to creep mysteriously in and out of my nostrils. He smiled and explained that the Hawaiian word alahee literally means “to move through the forest like an octopus.”

Today we can only imagine what these complex ecosystems looked like and guess at how they worked. Tragically, about 95 percent of Hawaii’s original dry forests have been destroyed, and many of their most ecologically important species are functionally, or actually, extinct. For example, most of the native birds and insects that once performed such critical services as flower pollination and seed scarification and dispersal are now gone. Many of the once dominant and culturally important canopy trees are also extinct or exist in only a few small populations of scattered and senescent individuals.

Today we can only imagine what these complex ecosystems looked like and guess at how they worked. Tragically, about 95 percent of Hawaii’s original dry forests have been destroyed, and many of their most ecologically important species are functionally, or actually, extinct. For example, most of the native birds and insects that once performed such critical services as flower pollination and seed scarification and dispersal are now gone. Many of the once dominant and culturally important canopy trees are also extinct or exist in only a few small populations of scattered and senescent individuals.

The demise of Hawaii’s dry forests began soon after the Polynesian discovery of these islands around 400 A.D. Like indigenous people throughout the tropics, the early Hawaiians cleared and burned the dry coastal forests and converted them into cultivated grasslands, agricultural plantations and thickly settled villages. Captain James Cook’s arrival in 1778 set in motion a chain of events that dramatically accelerated the scope and intensity of habitat destruction and species extinctions throughout the Hawaiian Islands. While the Polynesians had deliberately brought many new species to Hawaii in their double-hulled sailing canoes (and some stowaways such as the Polynesian rat, geckos, skinks and various weeds), their impact was trivial compared to the ecological bombs dropped by the Europeans. Thinking the islands deprived of some of God’s most useful and important species, Cook and his successors, with the best of intentions, set free cows, sheep, deer, goats, horses and pigs. Over time, foreigners from around the world unleashed a veritable Pandora’s box of more ecological wrecking machines, including two more species of rats, mongooses (in an infamously ill-advised attempt to control the rats), mosquitoes, ants and a diverse collection of noxious weeds. These included the African fountain grass that scratched my bare arms and legs as I struggled to reach the burnt forest.

During relatively rainy periods, when fountain grass greens up and is in full bloom, large swaths of the leeward side of the Big Island can look like a lush Midwestern prairie. But inevitably, the merciless kona (leeward) sunshine returns, and the rains disappear for months on end. The fountain grass dries to a sickly brown; then all it takes is somebody to park their hot car over a clump of grass for the whole region to burst into flame like a barn full of dry hay. In contrast to most Hawaiian species, fountain grass originated within a savanna ecosystem that regularly burned, and consequently has had thousands of years to evolve mechanisms to cope with and even exploit large-scale fires. I have watched fountain grass rise up from its ashes like a green phoenix after several seemingly devastating wildfires: Vigorous new shoots quickly appear within the old burned clumps, seeds germinate en masse and the emerging seedlings rapidly establish within the favorable post-fire environment of increased light and nutrients and decreased plant competition.

The net result of these fires is thus more fountain grass and less native dry forest. More grass means that during the next drought there will be even greater fuel loads, which in turn leads to more frequent and widespread fires. This growing cycle of alien grass and fire has proven to be the nail in the coffin for dry forests on the Big Island and throughout the tropics as a whole. The reason we don’t hear about campaigns to save tropical dry forests is because there are now virtually no such forests left to save. If we want at least some semblance of this ecosystem to exist in the future, we’ll have to deliberately and painstakingly design, plant, grow and care for them ourselves.

The net result of these fires is thus more fountain grass and less native dry forest. More grass means that during the next drought there will be even greater fuel loads, which in turn leads to more frequent and widespread fires. This growing cycle of alien grass and fire has proven to be the nail in the coffin for dry forests on the Big Island and throughout the tropics as a whole. The reason we don’t hear about campaigns to save tropical dry forests is because there are now virtually no such forests left to save. If we want at least some semblance of this ecosystem to exist in the future, we’ll have to deliberately and painstakingly design, plant, grow and care for them ourselves.

As I approached the dead trees, I was hot and frustrated that I had not even seen this forest before it burned. Yet in a bittersweet way I was glad that I had never been there, because even without any personal connection to this place, the sight of those wrecked trees was almost unbearably depressing. This had apparently been one of the best native dry forest remnants left within the entire state, but now we would never know which species had lived here, and we would never be able to collect seeds or cuttings from its gnarled old trees that were now on the very edge of extinction.

I looked back upslope at our tiny parcels of native trees straddling the highway. To preserve and restore these forest remnants, our Dryland Forest Working Group collectively spent thousands of hours installing fire breaks, killing fountain grass and exotic rodents, collecting seeds, and propagating and transplanting thousands of native plants. Local groups ranging from troubled Hawaiian teenagers to real estate agents had repeatedly donated their time and labor to help with these efforts. Hundreds of people within and beyond the Hawaiian Islands had come to see and study this ecosystem. My own scientific research program had progressed from documenting the demise of these forests to experimenting with promising techniques for restoring them at ever-larger spatial scales.

I looked back upslope at our tiny parcels of native trees straddling the highway. To preserve and restore these forest remnants, our Dryland Forest Working Group collectively spent thousands of hours installing fire breaks, killing fountain grass and exotic rodents, collecting seeds, and propagating and transplanting thousands of native plants. Local groups ranging from troubled Hawaiian teenagers to real estate agents had repeatedly donated their time and labor to help with these efforts. Hundreds of people within and beyond the Hawaiian Islands had come to see and study this ecosystem. My own scientific research program had progressed from documenting the demise of these forests to experimenting with promising techniques for restoring them at ever-larger spatial scales.

Looking at the fruits of our work from this distance, I felt a wave of optimism sweep over me, and for the first time truly believed that even this saddest of all the sad Hawaiian ecosystems could be saved. I turned around again and looked at the scorched trees. “We can grow another forest here,” I muttered. “We know what to do, and how to do it.” I stomped on a clump of resprouting fountain grass, slung on my pack and marched back up to the highway to get to work.

Robert Cabin is an associate professor of ecology and environmental science at Brevard College. This article is adapted from his book Intelligent Tinkering: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Practice, which will be published by Island Press this summer (ISBN: 9781597269643). You can read Bob’s views on environmental issues in his Huffington Post blog.