Fall 2016

Editor’s Note

“Ultimately, Marlboro’s small size is a strength,” says alumnus Aaron Kisicki, an attorney for the state of Vermont profiled in this issue of Potash Hill (page 46). “If you want to experience a community that is like-minded, in terms of significant intellectual engagement with ideas of personal interest, you’re always going to end up with smaller numbers.” Not only is small beautiful, it is a function of Marlboro’s core mission to teach students to think independently and be part of a learning community.

“Ultimately, Marlboro’s small size is a strength,” says alumnus Aaron Kisicki, an attorney for the state of Vermont profiled in this issue of Potash Hill (page 46). “If you want to experience a community that is like-minded, in terms of significant intellectual engagement with ideas of personal interest, you’re always going to end up with smaller numbers.” Not only is small beautiful, it is a function of Marlboro’s core mission to teach students to think independently and be part of a learning community.

Marlboro’s small wonder is highlighted in the first of many editorials from President Kevin, titled “Tiny Colleges Matter,” and in the instructive slice of fundraising history from former Marlboro development chief Will Wootton’s upcoming memoir. It shines through in the U.S. News & World Report #1 ranking of lowest student-faculty ratio, and in Jean O’Hara and Jodi Clark’s pioneering course in community. This issue of Potash Hill is jam-packed with smallness.

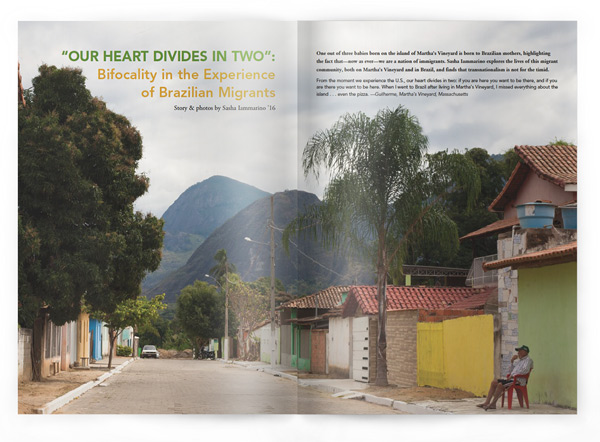

We start off with a vivid example of Marlboro’s strength in smallness, of students “engaging in what they are doing in a significant way.” Sasha Iammarino’s photo essay on migrants from Brazil illustrates that no place is an island, not even an island like Martha’s Vineyard. There has been a lot of talk about immigration in the past year, but Sasha’s nuanced research brings the individual stories behind transnationalism into focus in a way that no political campaign can.

Speaking of small, did I mention that your very own alumni magazine has once again won an excellence award from the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE)? Potash Hill won bronze in the CASE District 1 overall category for magazines with a circulation of 50,000 and under. With a circulation of only 5,000, this is yet another surprising example of Marlboro’s Mighty-Mouse-like powers. Learn more.

What do you think are Marlboro’s greatest strengths? What is your fondest memory of life in an intentionally small learning community? Share your thoughts, big and small, with us at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

—Philip Johansson

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the undergraduate campus was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Chief External Relations Officer: Matthew Barone

Alumni Director: Kathy Waters

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Ella McIntosh

Staff Photographers: Ben Rybisky ’18 and Lindsay Stevens ’17

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: A graffiti-adorned building in São Paulo, Brazil, gives conflicting signals of both progress and decline, security and vulnerability, optimism and despair. Similar conflicts are felt by migrants who divide their lives between Brazil and the U.S., as revealed in a recent graduate’s research on Brazilian migrants (page 8). Photo by Sasha Iammarino

“This is a place for you to learn you,” says Malachie Reilly ’17 (pictured right) in a recent video profile about pursuing his passion at Marlboro. For Malachie, this includes playing every sport available to him, which is surprisingly many for a college that consistently ranks in Princeton Review’s top 10 for “There’s a Game?” See Malachie.

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our undergraduate campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, and our graduate center in Brattleboro, students engage in deep exploration of their interests—and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

Up Front

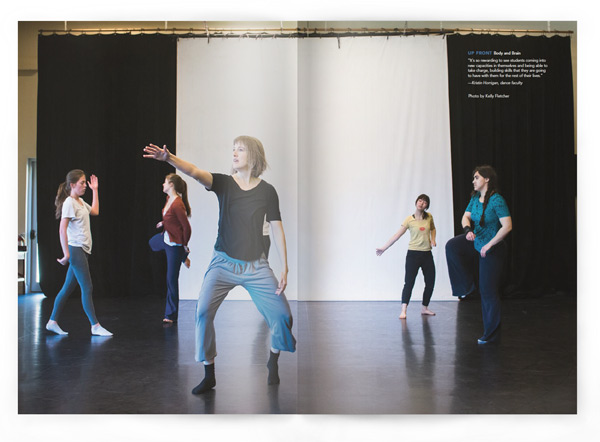

Body and Brain

“It’s so rewarding to see students coming into new capacities in themselves and being able to take charge, building skills that they are going to have with them for the rest of their lives.”

—Kristin Horrigan, dance faculty

Photo by Kelly Fletcher

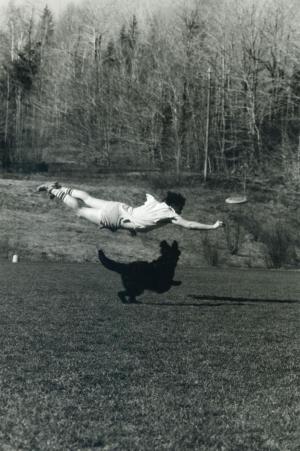

Clear Writing

The Conversation Pit

By John Sheehy

Imagine the academic world as a room in which a heated conversation is going on, and has been going on for quite some time. You have been invited into that room, and you want to join the conversation—but you’re coming in late, and the conversation has already taken on a momentum. How do you join that conversation intelligently?

Probably, you take some time to listen to it before you jump in: you want to find out what people are saying, who is on what side of which issues, which ideas have already been brought up, which ideas have been done to death; you need to find out what has and hasn’t been said before you’ll be able to enter the conversation in a way that the other people in the room will find interesting. The time you spend listening to the conversation is your research—and, of course, your contribution is your research paper.

Most people begin their research too late: they come up with a topic, they develop a claim and an argument around that topic, and only then do they go to the library and start doing research. Last-minute research almost inevitably becomes a quote hunt—the writer goes into it with a preconceived notion about his or her topic, and all he or she is doing in the library is hunting through research material hoping to find a sentence or two that seems to support that notion.

Chances are, what the writer is doing has already been done—that is, the academic conversation has already gone over that ground—but last-minute researchers never find that out. They don’t have time; as a result, they miss the opportunity to really learn anything from the people who have already worked on their topic.

A better research technique is to hit the library after you’ve found an interesting topic, but before you’ve completely formulated your position on that topic. If you give it plenty of time, your research can feed your thinking about your topic, and can help you come up with a much more interesting paper. Don’t think of secondary research as something you insert into a finished paper to make it better—think of it as the soil from which a good paper can grow.

From a long-ago “tip sheet” handout by John Sheehy, professor of writing and literature and grand poobah of the Clear Writing Program. Learn more. Photo by Peter Peck

Letters

Pet Fetish

A tale of democracy in action from Tim Little ’65

“When I was a student there was a rule against pets. And so someone—I know who it was but I won’t say his name—someone brought a pet on campus. It was a dog, a very nice dog, named for the very famous Argentine car racer Juan Manuel Fangio—so he was Fangio. The Town Meeting passed a resolution that made Fangio a person, and then excused him from paying tuition. And so he lived on the top floor of Mather.

“When I was a student there was a rule against pets. And so someone—I know who it was but I won’t say his name—someone brought a pet on campus. It was a dog, a very nice dog, named for the very famous Argentine car racer Juan Manuel Fangio—so he was Fangio. The Town Meeting passed a resolution that made Fangio a person, and then excused him from paying tuition. And so he lived on the top floor of Mather.

“The biggest thing Fangio was able to do was befriend Don Woodard, the man who did all the buildings and grounds, the only one who did all of that. Don was also the sheriff of Marlboro, and lived on campus. He was a very difficult man to get along with, although I never had any trouble with him at all. But he took to Fangio, and so that meant that Fangio could stay.”

No, the noble beast pictured (right) is not Fangio, but perhaps you know her name and degree field? Do you have a favorite pet story, pet peeve, or pet name from your days at Marlboro? If you have a Marlboro memory to share, or any other reflection from this issue of Potash Hill, send it to pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

Loving Potash

I read the magazine and was duly impressed!

—Deborah Beale ’69

Creative Thinkers

The letter from Geoffrey Hendricks about wanting “creative thinkers to make up the board beside the traditional lawyers and bankers” brings me to the inside back cover. Sitting with the young Tom Ragle is one of the “traditional bankers,” Henry Z. Persons, president of the Brattleboro Savings & Loan. My husband, Paul Olson, was one of the “traditional lawyers,” and he told me the following story from the 1950s.

Paul was sitting home one Sunday afternoon, minding his own business, when he spied Zee Persons and Arthur Whittemore trudging up the drive. They had come to ask him to be the trustee in bankruptcy for Marlboro College. His first reaction was to refuse, but they tossed it around for a while and he finally said he’d think it over. A day or two later he and Zee got together and indulged in some superbly “creative thinking” that resulted in the rescue of the college and their enduring friendship.

—Dorothy Olson, friend

Ultimate Memories As I was flipping through the latest edition of Potash Hill I caught a glimpse of a photo and thought, “Oh, look, they printed the picture of Kip (Morgan ’86) making a diving Frisbee catch.” I think it’s also worth noting that Kip was (in)famous for his diving catches. Our Ultimate Frisbee “team” played a few other colleges: Hampshire, Williams, and Bennington come to mind. We called ourselves “The Marlboro Moo-Jah-Hadin,” back when we considered those fighting the invading Westerners (Russians at that time) in Afghanistan to be “freedom fighters” instead of “terrorists.” The “Moo” part is of course a reference to Vermont agriculture, and the “Jah” part is a reference to our, um, proclivities, the genetic source of which was also Afghanistan, and our method was guerilla agriculture. So it all worked together quite nicely. I do not remember the dog, however.

As I was flipping through the latest edition of Potash Hill I caught a glimpse of a photo and thought, “Oh, look, they printed the picture of Kip (Morgan ’86) making a diving Frisbee catch.” I think it’s also worth noting that Kip was (in)famous for his diving catches. Our Ultimate Frisbee “team” played a few other colleges: Hampshire, Williams, and Bennington come to mind. We called ourselves “The Marlboro Moo-Jah-Hadin,” back when we considered those fighting the invading Westerners (Russians at that time) in Afghanistan to be “freedom fighters” instead of “terrorists.” The “Moo” part is of course a reference to Vermont agriculture, and the “Jah” part is a reference to our, um, proclivities, the genetic source of which was also Afghanistan, and our method was guerilla agriculture. So it all worked together quite nicely. I do not remember the dog, however.

—Markus Brakhan ’86

I recognize the photo on page 7 of the Spring 2016 issue. That is Kip Morgan ’86. I don’t remember the dog.

—Anders Newcomer ’86

I can’t tell you who the dog is, but the guy in the Frisbee photo is Christopher “Kip” Morgan ’86.

—John Ruble ’86

That’s Kip Morgan ’86. We were so fired up on Ultimate Frisbee in those days . . . we would run through the dorms chanting “Ultimate!” and rally the games. We would occasionally play against Hampshire College, but mostly just had a great time. I don’t recall the dog’s name, although Kip landed clean!

—James Dickey ’88

And from a related facebook thread

Now that was a fun day—as were they all at Marlboro. Christina Faggi (’84) took the pic with Boo Stearns’ (’86) camera. Pretty sure it was Jim Dickey who threw it, and I was lucky enough to catch it. We used to practice layouts on the field. The pic made the back cover of Potash Hill that season. My 15 minutes . . .

—Kip Morgan ’86

We have it on good authority that the dog is Fang, who belonged to Douglas Noyes ’83, not to be confused with Fangio. —Eds.

Trustee Tribulations

This is written in the spirit of what Dick Judd used to call an “instructional” letter. I am seeing in many places these days the spurious claim that Robert Frost was Marlboro College’s first trustee. There is no truth to this statement. The college’s first trustee was

Arthur Whittemore, a fact that was once and should continue to be well understood at the college. Frost was, in actual fact, the first person formally asked to become a trustee, and we know that request was made on August 6, 1946, in Ripton. There is a big difference between being the first trustee and the first person asked to be a trustee. Arthur Whittemore, a summer resident of Marlboro who later became an esteemed Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Justice, had been laying the groundwork for the college through the early part of that summer with Walter Hendricks, and there had been an understanding from the beginning, perhaps as early as that spring and maybe before, that he would lead the board.

Although Frost’s influence had helped plant the seed for the idea of a college in Walter’s imagination, prior to Walter Hendricks’ visit to Frost’s cabin in Ripton on August 6, Frost had not heard of the soon-to-be Marlboro College. Hence, Frost may well have been the second trustee, but there is perhaps no way of knowing for sure. What we do know is that he never attended a trustees’ meeting, and it was clear from the beginning that Walter Hendricks never expected him to. Frost once signed a book to Walter “From your trusted but untrustworthy trustee,” a tacit and humorous acknowledgement that he was a trustee in name only.

If Frost had a formal (actually, quite informal) responsibility at the college he took seriously it was his role as a “Visiting Associate in Teaching.” There Frost made a real difference with Marlboro students and he did it, characteristically, on his own terms.

—Dan Toomey ’79

“Our Heart Divides in Two”: Bifocality in the Experience of Brazilian Migrants

Story & photos by Sasha Iammarino ’16

Story & photos by Sasha Iammarino ’16

One out of three babies born on the island of Martha’s Vineyard is born to Brazilian mothers, highlighting the fact that—now as ever—we are a nation of immigrants. Sasha Iammarino explores the lives of this migrant community, both on Martha’s Vineyard and in Brazil, and finds that transnationalism is not for the timid.

"From the moment we experience the U.S., our heart divides in two: if you are here you want to be there, and if you are there you want to be here. When I went to Brazil after living in Martha’s Vineyard, I missed everything about the island . . . even the pizza."

—Guilherme, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

Beginning in the latter part of the 1980s, a small-scale migration emerged from within the Brazilian towns of Mantenópolis and Cuparaque, near the city of Governador Valadares, to one location in the United States: Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Although the influence of this migration is apparent in the large houses and businesses built by migrants in both Brazilian towns, there are few sources of information about how these migrants became incorporated into Martha’s Vineyard while remaining active in the towns they come from. The changed lives of these mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses, as they are called, are embedded in the individual stories of the people who migrated, their families, and their friends.

Beginning in the latter part of the 1980s, a small-scale migration emerged from within the Brazilian towns of Mantenópolis and Cuparaque, near the city of Governador Valadares, to one location in the United States: Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Although the influence of this migration is apparent in the large houses and businesses built by migrants in both Brazilian towns, there are few sources of information about how these migrants became incorporated into Martha’s Vineyard while remaining active in the towns they come from. The changed lives of these mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses, as they are called, are embedded in the individual stories of the people who migrated, their families, and their friends.

As part of my Plan of Concentration research, I conducted surveys and interviews with Brazilian migrants who live on Martha’s Vineyard, as well as those who have returned to Brazil after living on the island. I conducted all of the interviews in Portuguese and translated them into English myself. The voices of the people I interviewed best articulate the difficulty migrants face as they attempt to improve their lives and the ways they negotiate their experiences both in their place of origin and on Martha’s Vineyard.

It is really difficult, because our family stays there [Mantenópolis]. His father is there, my mother, my two uncles, and other relatives. Our family weighs on our desire to return to Brazil… It is easier for my children to return to Brazil and then come back here. I want to send them there to visit Brazil.

It is really difficult, because our family stays there [Mantenópolis]. His father is there, my mother, my two uncles, and other relatives. Our family weighs on our desire to return to Brazil… It is easier for my children to return to Brazil and then come back here. I want to send them there to visit Brazil.

–Júlia, 26 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

The majority of Brazilians that go to the island in the work season go thinking about how much they can save, so they return. We were not like that. We wanted a stable life there. But the money that we ended up saving up, after being there for a while, we started investing in Mantenópolis…. We were born here, we grew up here, we are familiar with here, so we came here. We returned to Mantenópolis.

–Marlene, 45 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

It is a cultural story…. So many Americans that go to Brazil want to live there. So why can’t we do the same here? I know people from my town [Mantenópolis] that are married to Americans, have a family here [Martha’s Vineyard], have children, the husband already speaks Portuguese, or vice versa, the American wife learns Portuguese. So there is this mixture. This migration is renewing itself, the culture of the country… there is that thing going on here—how do you say it—the intermixing of culture.

It is a cultural story…. So many Americans that go to Brazil want to live there. So why can’t we do the same here? I know people from my town [Mantenópolis] that are married to Americans, have a family here [Martha’s Vineyard], have children, the husband already speaks Portuguese, or vice versa, the American wife learns Portuguese. So there is this mixture. This migration is renewing itself, the culture of the country… there is that thing going on here—how do you say it—the intermixing of culture.

–Guilherme, 36 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

I wanted to go back to Brazil because of my family. I also worked too much, and it got to the point where I was too tired…. My experience there was good, but if we didn't have to work so much... There are a lot of people who say that Brazilians are made into slaves once they are in the U.S., but the reality is that we make ourselves into slaves when we are here. Because we want to return soon, and the more we work the faster we will return.

–Victória, 45 years old, lives in Cuparaque

I don’t want to leave here; I really like it here. It is tranquil. The life of my children is good because I have peace here. I have the peace to sleep with my front door unlocked the whole night. Things are changing, but compared to other places this is paradise. In Mantenópolis it is much more difficult… because people still struggle there a lot in general. And unfortunately Mantenópolis is really violent, there is a lack of security, a lack of order, so it is still pretty bad there. I enjoy traveling there because our family is there. But I prefer to live here.

I don’t want to leave here; I really like it here. It is tranquil. The life of my children is good because I have peace here. I have the peace to sleep with my front door unlocked the whole night. Things are changing, but compared to other places this is paradise. In Mantenópolis it is much more difficult… because people still struggle there a lot in general. And unfortunately Mantenópolis is really violent, there is a lack of security, a lack of order, so it is still pretty bad there. I enjoy traveling there because our family is there. But I prefer to live here.

–Carla, 34 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

The decision to leave is much more difficult than to come here. Especially after we have children. Unfortunately, our country’s culture is sad…. Of course it’s not everyone in Brazil… but unfortunately the majority of people are complicated…. And ours [our family] say in Brazil: Don’t come back because you miss us, stay there in the U.S., the situation in Brazil is not good. So our relatives also weigh on our decision to stay here.

–Júlia, 28 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

There are many Brazilians who come here and don’t ever go back [to Brazil]. There is Zezinho, who has been here for 12 years and does not plan on returning. There is my wife’s cousin who works with me, who has been here for a long time, and he wants to build a house on Martha’s Vineyard. Many Brazilian migrants here are like that… Sometimes there are some who want to return to Brazil, that arrive tired, and tire themselves out by working, and they want to return.

–Eliton, 34 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

We grew up here [Martha’s Vineyard]…and this is like our life. You know? So I don’t know if people can get used to Brazil anymore… because life in Brazil is so different from here; it’s much more difficult… Here we work, travel, you can go to a store and buy what you want…. It’s one thing for you to visit Brazil, but it’s a completely different thing to live there, understand?

We grew up here [Martha’s Vineyard]…and this is like our life. You know? So I don’t know if people can get used to Brazil anymore… because life in Brazil is so different from here; it’s much more difficult… Here we work, travel, you can go to a store and buy what you want…. It’s one thing for you to visit Brazil, but it’s a completely different thing to live there, understand?

–Lila, 23 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

I would work so much, hard work. I would work 16 hours per day. My boss really liked the way I worked because I did it well. So each day I learned more and developed my English skills. I really like it there, but I can’t work because I have a serious back injury that I think is a result from the work I did over there—that is the problem… Because the U.S. is good when you work, you have to work.

–Lúcia, 47 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

I was disappointed with the way I was treated on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, the cold serious way…. Here you are living around Brazilians, you see the heat, the “Hey how are? You good?” where Americans are like: “Hi.” I will confess, on Martha’s Vineyard I felt as an intruder who arrived to your land and was in the way of your lives…. I got there and had to be a slave, a country guy, just another person in the middle of many.

–Neto, 39 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

The majority of mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses who migrate to Martha’s Vineyard do so for the prospect of improving their economic situation, but the emotional dimension is also an important aspect. Guilherme’s emotional comparison of Martha’s Vineyard and Mantenópolis, quoted above, is “bifocal.” In my study I use bifocality as a way to explore how Brazilians navigate their experiences on Martha’s Vineyard relative to their birth towns of Cuparaque and Mantenópolis. Through their ability to relate to one location while living in the other, they develop a perspective that includes a focus on both their origins and their future, on “rooting and routing.”

The majority of mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses who migrate to Martha’s Vineyard do so for the prospect of improving their economic situation, but the emotional dimension is also an important aspect. Guilherme’s emotional comparison of Martha’s Vineyard and Mantenópolis, quoted above, is “bifocal.” In my study I use bifocality as a way to explore how Brazilians navigate their experiences on Martha’s Vineyard relative to their birth towns of Cuparaque and Mantenópolis. Through their ability to relate to one location while living in the other, they develop a perspective that includes a focus on both their origins and their future, on “rooting and routing.”

Within the transnational process of maintaining a connection between their hometowns and Martha’s Vineyard, through remittances, travel, and social media, many mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses develop a reality that is based on both locations simultaneously. They continue their customs of origin to overcome feelings of isolation on Martha’s Vineyard, while familiarizing themselves with the life dynamics of the island and finding a place where they fit in. Bifocality is a dual frame of reference in which migrants find a sense of belonging in both Brazil and Martha’s Vineyard, reshaping their reality and goals and causing them to consider a life that is beyond one location or the other.

Sasha Iammarino graduated in May with a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies (World Studies Program) and a Plan in anthropology and photography, specifically on the sending and receiving travel patterns of Brazilians on Martha’s Vineyard. She plans to continue her research in Brazil and the U.S.

Spirits and Memory “The narratives of people who lived through the Khmer Rouge era and resettled in the United States are characterized by disruption and displacement,” says Emily Tatro, who also completed a Plan on the emigrant experience. She explored the medical and spiritual beliefs of Cambodians and Cambodian Americans, a population profoundly affected by political tumult, violence, and war. “Spirits deeply impact emigrants, altering the linearity of time and infiltrating the porousness of memory,” says Emily. “Spirits speak to the often-silenced ruptures, absences, and losses that characterize emigrants’ experiences.” Emily conducted her research fully aware that the stories she collected rested on social, political, and cosmological ground that continues to shift, and aware of her own biases as an outsider. “I include my own stories to remind me of my inescapable subjectivity.” Photo by John Willis

“The narratives of people who lived through the Khmer Rouge era and resettled in the United States are characterized by disruption and displacement,” says Emily Tatro, who also completed a Plan on the emigrant experience. She explored the medical and spiritual beliefs of Cambodians and Cambodian Americans, a population profoundly affected by political tumult, violence, and war. “Spirits deeply impact emigrants, altering the linearity of time and infiltrating the porousness of memory,” says Emily. “Spirits speak to the often-silenced ruptures, absences, and losses that characterize emigrants’ experiences.” Emily conducted her research fully aware that the stories she collected rested on social, political, and cosmological ground that continues to shift, and aware of her own biases as an outsider. “I include my own stories to remind me of my inescapable subjectivity.” Photo by John Willis

Good Fortune Next Time

By Will Wootton ’72

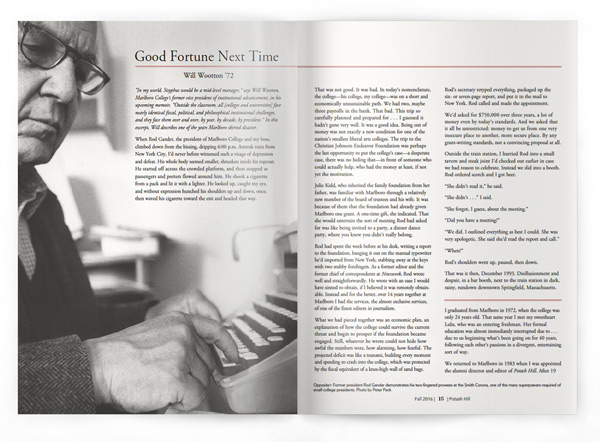

“In my world, Sisyphus would be a mid-level manager,” says Will Wootton, Marlboro College’s former vice president of institutional advancement, in his upcoming memoir. “Outside the classroom, all [colleges and universities] face nearly identical fiscal, political, and philosophical institutional challenges, and they face them over and over, by year, by decade, by president.” In this excerpt, Will describes one of the years Marlboro skirted disaster.

When Rod Gander, the president of Marlboro College and my boss, climbed down from the hissing, dripping 6:00 p.m. Amtrak train from New York City, I’d never before witnessed such a visage of depression and defeat. His whole body seemed smaller, shrunken inside his topcoat. He started off across the crowded platform, and then stopped as passengers and porters flowed around him. He shook a cigarette from a pack and lit it with a lighter. He looked up, caught my eye, and without expression hunched his shoulders up and down, once, then waved his cigarette toward the exit and headed that way.

When Rod Gander, the president of Marlboro College and my boss, climbed down from the hissing, dripping 6:00 p.m. Amtrak train from New York City, I’d never before witnessed such a visage of depression and defeat. His whole body seemed smaller, shrunken inside his topcoat. He started off across the crowded platform, and then stopped as passengers and porters flowed around him. He shook a cigarette from a pack and lit it with a lighter. He looked up, caught my eye, and without expression hunched his shoulders up and down, once, then waved his cigarette toward the exit and headed that way.

That was not good. It was bad. In today’s nomenclature, the college—his college, my college—was on a short and economically unsustainable path. We had two, maybe three payrolls in the bank. That bad. This trip so carefully planned and prepared for . . . I guessed it hadn’t gone very well. It was a good idea. Being out of money was not exactly a new condition for one of the nation’s smallest liberal arts colleges. The trip to the Christian Johnson Endeavor Foundation was perhaps the last opportunity to put the college’s case—a desperate case, there was no hiding that—in front of someone who could actually help, who had the money at least, if not yet the motivation.

Julie Kidd, who inherited the family foundation from her father, was familiar with Marlboro through a relatively new member of the board of trustees and his wife. It was because of them that the foundation had already given Marlboro one grant. A one-time gift, she indicated. That she would entertain the sort of meeting Rod had asked for was like being invited to a party, a dinner dance party, where you knew you didn’t really belong.

Rod had spent the week before at his desk, writing a report to the foundation, banging it out on the manual typewriter he’d imported from New York, stabbing away at the keys with two stubby forefingers. As a former editor and the former chief of correspondents at Newsweek, Rod wrote well and straightforwardly. He wrote with an ease I would have sinned to obtain, if I believed it was remotely obtainable. Instead and for the better, over 14 years together at Marlboro I had the services, the almost exclusive services, of one of the finest editors in journalism.

What we had pieced together was an economic plan, an explanation of how the college could survive the current threat and begin to prosper if the foundation became engaged. Still, whatever he wrote could not hide how awful the numbers were, how alarming, how fearful. The projected deficit was like a tsunami, building every moment and speeding to crash into the college, which was protected by the fiscal equivalent of a knee-high wall of sand bags.

Rod’s secretary retyped everything, packaged up the six- or seven-page report, and put it in the mail to New York. Rod called and made the appointment.

We’d asked for $750,000 over three years, a lot of money even by today’s standards. And we asked that it all be unrestricted: money to get us from one very insecure place to another, more secure place. By any grant-writing standards, not a convincing proposal at all.

Outside the train station, I hurried Rod into a small tavern and steak joint I’d checked out earlier in case we had reason to celebrate. Instead we slid into a booth. Rod ordered scotch and I got beer.

“She didn’t read it,” he said.

“She didn’t . . .” I said.

“She forgot, I guess, about the meeting.”

“Did you have a meeting?”

“We did. I outlined everything as best I could. She was very apologetic. She said she’d read the report and call.”

“When?” Rod’s shoulders went up, paused, then down.

That was it then, December 1993. Disillusionment and despair, in a bar booth, next to the train station in dark, rainy, rundown downtown Springfield, Massachusetts.

***

I graduated from Marlboro in 1972, when the college was only 24 years old. That same year I met my sweetheart Lulu, who was an entering freshman. Her formal education was almost immediately interrupted due to . . . due to us beginning what’s been going on for 40 years, following each other’s passions in a divergent, entertaining sort of way.

I graduated from Marlboro in 1972, when the college was only 24 years old. That same year I met my sweetheart Lulu, who was an entering freshman. Her formal education was almost immediately interrupted due to . . . due to us beginning what’s been going on for 40 years, following each other’s passions in a divergent, entertaining sort of way.

We returned to Marlboro in 1983 when I was appointed the alumni director and editor of Potash Hill. After 19 years there I was vice president of institutional advancement and Marlboro had grown from a perilously low 167 students to just over 300.

Among independent colleges and universities, there are financially shaky ones: old, settled in their ways, and constantly aging badly. There are colleges newly born, others approaching adolescence, and still others finally nearing something like adulthood after 70 or 80 years of hard living. There are huge 20,000-student universities, and colleges with thousands of undergraduates, and finally there are tiny places like Marlboro, shrews dodging the footfalls of dinosaurs.

Marlboro and Sterling College in northern Vermont, where I served as president from 2006 to 2012 and where there are just over 100 students, are distinguished not only by their size but also by their unusual curricula, their history, place, and people. It hardly matters, in one sense, because in the context of American higher education each is unknown, underendowed, underfunded, and, worst of all, practically unimaginable to the general college aspirant: a whole college considerably smaller than your high school graduating class. How could that be?

Each is further notable for having more than once skirted dangerously close to the sheer cliff edge of institutional oblivion. Today both remain small, so tiny that anyone who claims to know anything about higher education—and there are millions who do—would predict their near-immediate demise with an air of complete assurance, simply because of their obscurity and ridiculous, uneconomical, and clearly unsustainable size.

Marlboro (somewhat erratically) and Sterling (somewhat compulsively) have spent a lot of their time figuring out how to stay small, how not to grow. They understand, as do some other Vermont colleges, that the diseconomy of scale is not the primary threat; that there are other, equally forbidding threats out there, including fiscal mismanagement, legal claims, lack of critical resources, shortfalls in admissions, board dysfunction, inept leadership, and increases in regulatory burden coinciding with any of the above. If it were as simple as being small, they all would have succumbed decades ago, and this memoir would not exist.

Among the couple thousand independent liberal arts colleges, the Ivies and the potted Ivies are cushioned by enormous endowments and their own gold-plated histories, shaped from studiously cultivated alumni, their alumni parents, and alumni children. There must be another thousand regional institutions, including faith-based colleges and universities, that are fiscally and institutionally sound and have been for generations.

Death and its dismissive cousin, death-by-merger, is reserved for the old and infirm, the shrinking, the undernourished, the timid, and for the young, the experimental, and specialized. To this segment of the industry, death visits quite often, especially in New England, where the college-going population has been in decline off and on for 20 years, while the competition from state institutions and for-profit colleges has surged.

In Vermont, Windham College succumbed in the early ’80s, as did the fledgling Mark Hopkins College before the decade was out, then Trinity in 2000, and Woodbury in 2008; in Massachusetts, Atlantic Union College closed in 2011 and Urban College of Boston in 2012; and in 2012 New Hampshire’s Chester College went under. Famously, Antioch, in Ohio, succumbed after more than a century (it reopened after some years, unaccredited and struggling). Recently Sweet Briar announced its closure, but the alumni rescued it, at least for the short term, and Burlington College closed its doors just this year.

For me, there’s a critical aspect to endemic institutional fragility: that for some of us, in some perverse way, it is the odds against a future that makes it all worthwhile, that justifies spending one’s effective working years at worthy places that, to express it gently, are not assured the level of stability enjoyed by their wealthier and better known partners in the higher education world.

***

Rod came into my office at Marlboro, down the hall from his, and plopped into the red, as opposed to green, chair. It had been days since we drove back from Springfield to Vermont and began waiting for Julie Kidd to call.

Rod came into my office at Marlboro, down the hall from his, and plopped into the red, as opposed to green, chair. It had been days since we drove back from Springfield to Vermont and began waiting for Julie Kidd to call.

I was typing a story for the alumni magazine, Potash Hill. I didn’t turn around.

“She called.” I stopped typing.

“She read it. She’s going to do the whole thing: $250,000 a year for three years. Unrestricted.”

The tsunami disappeared like fog does, like it was never seriously there. I turned around and saw Rod practically floating from the weight off his shoulders. He was grinning. He started to sing, holding up his palms—he knew the words to hundreds of tunes, from the ’20s to the mid-’50s: “We’re in the money / The sky is sunny / Old man depression, you are through.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s great. But what have you done today to save the place?”

“Not a thing,” he said. “I’m waiting for tomorrow when I tell the board we’re halfway to a balanced budget. And it’s only November. It reminds me of the newspaper hawker in Chicago. We’ll have to send him to another corner.”

“What hawker?”

“Whatever the headlines were, he stuck with only one call, over and over, for years: ‘Many Dead, Many Dying! Many Dead, Many Dying!’”

Will Wootton retired in 2012 after serving as president of Sterling College for six years, when he “ran out of things to do, stuff to fix, nearby streams to fish.” This article is excerpted and adapted from Will’s memoir, Good Fortune Next Time: Life, Death, Irony, and the Administration of Very Small Colleges, due to be released by Dryad Press in fall 2017. The same chapter in full, titled “Many Dead, Many Dying,” was previously excerpted in Santa Fe Writer’s Project Quarterly Issue 5, Spring 2016.

From Round Earth to Flat Hierarchies

By Lori Hanau

We once believed the earth to be flat. The moment we discovered it wasn’t, the possibilities of our existence and what we could accomplish began to expand exponentially. A paradigm shift is a fundamental change in view of how things work in the world, making visible what we couldn’t imagine before. So what about the way we work in the world?

We once believed the earth to be flat. The moment we discovered it wasn’t, the possibilities of our existence and what we could accomplish began to expand exponentially. A paradigm shift is a fundamental change in view of how things work in the world, making visible what we couldn’t imagine before. So what about the way we work in the world?

What is clear is that the established way of working isn’t working. According to reports that Gallup has been generating since 2000, two-thirds of employees today feel disengaged and experience a lack of meaning at work, costing the American economy an estimated $450–550 billion annually. Globally, the percentage of disengagement in the workplace is 87 percent across 142 countries.

Like all good paradigms, the way out of the problem comes when we see it with new eyes. Try to see the crisis at work as a call to shift how we relate to leadership. As challenges and opportunities approach whole-earth scale, we must cultivate new muscles for leading together, rooted in our innate abilities to accomplish organizational objectives and collectively impact social change. To change the way we work, we have to change the way we lead.

In the current paradigm, leadership is positional. We relate to our work first and foremost through our roles, our status, and our expertise in order to execute outcomes. This “boss” model of leadership requires those of us at the top to hold the answers, survive a universe of stress, and assume singular control over outcomes and others. Meanwhile, as employees, we feel more disconnected from our livelihood and we relinquish our agency at work.

I’ve defined “shared leadership” as “the practice of bringing out the greatest capacity in everyone by empowering each individual to be responsible for and engaged in the success of the whole.” This is a fundamental shift to lead from our personal and collective agency, in all that we are and all that we do. To lead consciously, we must shift our orientation from relating first through our roles, statuses, and expertise, to relating first through the genius of our humanity and equality, what exists at the core of us.

Shifting the leadership paradigm requires that we bring our whole selves to work, learning to lead from our humanity first. Think that’s scary? Imagine being told that the earth was round when everybody knew it was flat. Let’s be brave together and begin with the way we lead. We aren’t just shifting the paradigm around work and leadership. We are upgrading our humanity.

Lori Hanau is a graduate faculty member and co-chair of management programs, including the Collaborative Leadership concentration, and founder of Global Round Table Leadership. This article is excerpted from her editorial in the Fall 2015 issue of Conscious Company. Learn more at globalroundtableleadership.com.

Tiny Colleges Matter

By President Kevin Quigley

Across the U.S., families increasingly question the cost of higher education and voice mounting skepticism that such education will lead their children to a successful future. This questioning occurs against the backdrop of a highly politicized election year, where candidates are trumpeting plans for free—or greatly reduced cost for—public higher education, along with caps on the debt that families can incur. Diminutive Marlboro College is not alone in being buffeted by these challenging winds, perhaps more than much larger and better-endowed institutions, but we do have a unique perspective to bring to the table.

Across the U.S., families increasingly question the cost of higher education and voice mounting skepticism that such education will lead their children to a successful future. This questioning occurs against the backdrop of a highly politicized election year, where candidates are trumpeting plans for free—or greatly reduced cost for—public higher education, along with caps on the debt that families can incur. Diminutive Marlboro College is not alone in being buffeted by these challenging winds, perhaps more than much larger and better-endowed institutions, but we do have a unique perspective to bring to the table.

Recently, I attended a meeting with 14 other college presidents of what we described as “tiny” liberal arts colleges, hosted by the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation. We ranged from 75 students at Shimer College, in Chicago, to 700 at Bennington College, our closest liberal arts college neighbor. This group included a variety of curricular and pedagogic styles ranging from work colleges like Sterling College in Craftsbury Commons, Vermont; to the College of the Atlantic with its single major, Human Ecology; to St. John’s College with its Great Books curriculum; to Marlboro, where pedagogy is based on our dynamic first dean Roland Boyden’s famous description of the quintessence of education: a bench, a book, a teacher, and a student.

While we had considerable differences among us, each of these 15 tiny colleges believes that the intimacy of a small college setting is essential to fostering collegial, mentoring relationships between students and faculty, which other larger institutions aspire to but rarely achieve. Among this very special group of colleges, Marlboro stands out for our intensive focus on community and, in particular, for the Vermont-style Town Meeting that provides our community a role in the college’s governance.

This year, Marlboro received a planning grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations designed to build on our special traditions by further infusing citizenship and community service into the Marlboro experience. This is just one of the ways we are responding to the growing demand to offer students the skills and experience that will help them define success for themselves, and achieve it while contributing to the communities they become connected to in the future.

As a community, we are working to see recent enrollment challenges as an opportunity for learning and improvement, bringing us closer to the thriving Marlboro we all envision. There will be other challenges besides enrollment, but I am confident that community will continue to remain the vibrant core of all we do, in ways that distinguish Marlboro from even those tiny colleges with which we are most similar.

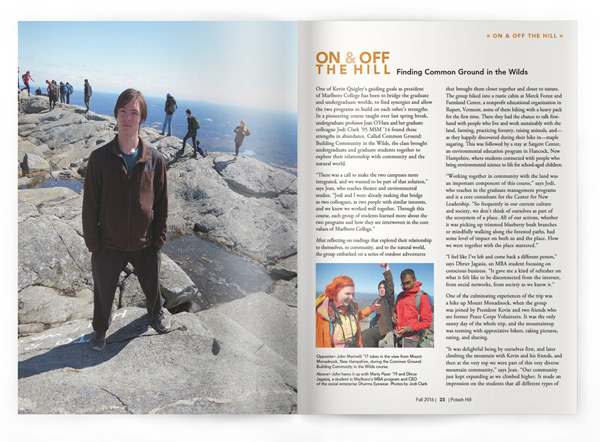

On & Off the Hill

Finding Common Ground in the Wilds

One of Kevin Quigley’s guiding goals as president of Marlboro College has been to bridge the graduate and undergraduate worlds, to find synergies and allow the two programs to build on each other’s strengths. In a pioneering course taught over last spring break, undergraduate professor Jean O’Hara and her graduate colleague Jodi Clark ’95 MSM ’14 found these strengths in abundance. Called Common Ground: Building Community in the Wilds, the class brought undergraduate and graduate students together to explore their relationship with community and the natural world.

One of Kevin Quigley’s guiding goals as president of Marlboro College has been to bridge the graduate and undergraduate worlds, to find synergies and allow the two programs to build on each other’s strengths. In a pioneering course taught over last spring break, undergraduate professor Jean O’Hara and her graduate colleague Jodi Clark ’95 MSM ’14 found these strengths in abundance. Called Common Ground: Building Community in the Wilds, the class brought undergraduate and graduate students together to explore their relationship with community and the natural world.

“There was a call to make the two campuses more integrated, and we wanted to be part of that solution,” says Jean, who teaches theater and environmental studies. “Jodi and I were already making that bridge as two colleagues, as two people with similar interests, and we knew we worked well together. Through this course, each group of students learned more about the two programs and how they are interwoven in the core values of Marlboro College.”

After reflecting on readings that explored their relationship to themselves, to community, and to the natural world, the group embarked on a series of outdoor adventures that brought them closer together and closer to nature. The group hiked into a rustic cabin at Merck Forest and Farmland Center, a nonprofit educational organization in Rupert, Vermont, some of them hiking with a heavy pack for the first time. There they had the chance to talk firsthand with people who live and work sustainably with the land, farming, practicing forestry, raising animals, and— as they happily discovered during their hike in—maple sugaring. This was followed by a stay at Sargent Center, an environmental education program in Hancock, New Hampshire, where students connected with people who bring environmental science to life for school-aged children.

Working together in community with the land was an important component of this course,” says Jodi, who teaches in the graduate management programs and is a core consultant for the Center for New Leadership. “So frequently in our current culture and society, we don’t think of ourselves as part of the ecosystem of a place. All of our actions, whether it was picking up trimmed blueberry bush branches or mindfully walking along the forested paths, had some level of impact on both us and the place. How we were together with the place mattered.”

Working together in community with the land was an important component of this course,” says Jodi, who teaches in the graduate management programs and is a core consultant for the Center for New Leadership. “So frequently in our current culture and society, we don’t think of ourselves as part of the ecosystem of a place. All of our actions, whether it was picking up trimmed blueberry bush branches or mindfully walking along the forested paths, had some level of impact on both us and the place. How we were together with the place mattered.”

“I feel like I’ve left and come back a different person,” says Dhruv Jagasia, an MBA student focusing on conscious business. “It gave me a kind of refresher on what it felt like to be disconnected from the internet, from social networks, from society as we know it.”

One of the culminating experiences of the trip was a hike up Mount Monadnock, when the group was joined by President Kevin and two friends who are former Peace Corps Volunteers. It was the only sunny day of the whole trip, and the mountaintop was teeming with appreciative hikers, taking pictures, eating, and sharing.

“It was delightful being by ourselves first, and later climbing the mountain with Kevin and his friends, and then at the very top we were part of this very diverse mountain community,” says Jean. “Our community just kept expanding as we climbed higher. It made an impression on the students that all different types of people worked their way up this difficult climb and that the president took the time to be with them for a full day’s hike.”

A Fresh Look at Curriculum

Marlboro understandably takes pride in an academic program rich with interdisciplinary possibilities and supportive of the intellectual passions of its students. In the interest of that ongoing support, the faculty have been looking critically at the curriculum, leading to exciting initiatives that will be evolving and unfolding over the coming years. One of these is an elective course on living and working in community, introduced as a pilot this fall. The other has to do with making a clearer and more consistent “progression” from the sophomore year to being “on Plan.”

Marlboro understandably takes pride in an academic program rich with interdisciplinary possibilities and supportive of the intellectual passions of its students. In the interest of that ongoing support, the faculty have been looking critically at the curriculum, leading to exciting initiatives that will be evolving and unfolding over the coming years. One of these is an elective course on living and working in community, introduced as a pilot this fall. The other has to do with making a clearer and more consistent “progression” from the sophomore year to being “on Plan.”

“These are both initiatives that are still in progress but that signal a move toward better integration between what we say we do, what we actually do, and what we aspire to do,” says Brenda Foley, theater professor and member of the Renaissance Group, which coordinated the initiatives.

“The Progression is the most complete and sweeping change to come out of this movement of review and reform,” said John Sheehy, literature and writing professor and another member of the Renaissance Group. “It is the result of some pretty serious rethinking of our advising model, and it enacts substantive changes in practice over the next couple of years.”

As it stands, the Progression is a proposed benchmark event that will help structure and solidify the transition from the first two years to the second two years at Marlboro. Supported by the building of a student portfolio starting on day one, and informed by the sophomore review, the Progression is a conversation between students and their advisors from which the preliminary Plan application emerges. The idea is to give this crucial period of transition more definition, while allowing for a range of approaches deemed valuable to individual faculty members and students.

“Although this will take some time to implement, it is an important beginning,” says John. “The process has been a valuable time for the faculty to put their hands under the hood and see what works. The point was never to ‘fix’ the college—the point was to re-engage, as faculty, with the curriculum. That we have done, and that we must continue to do.” Look for an article on the new course on living and working in community in the next issue of Potash Hill.

College Partners with ILI

“One of the biggest barriers to international students attending Marlboro College is the high proficiency in English needed to engage in academic scholarship,” says Maggie Strassman, director of international studies. That is changing, following a new partnership with the International Language Institute of Massachusetts (ILI), a Northampton-based, not-for-profit language school promoting intercultural understanding through language instruction.

“One of the biggest barriers to international students attending Marlboro College is the high proficiency in English needed to engage in academic scholarship,” says Maggie Strassman, director of international studies. That is changing, following a new partnership with the International Language Institute of Massachusetts (ILI), a Northampton-based, not-for-profit language school promoting intercultural understanding through language instruction.

Through an agreement signed by Marlboro and ILI in March, international students from around the world who need an English-language intensive program can start at ILI and then continue on at Marlboro to complete their education. Marlboro requires a TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) score of 90, among the highest proficiency requirements of cohort colleges, and ILI will make this more accessible.

“This is a perfect match,” says Brigid Lawler, dean of admissions. “ILI’s well-deserved reputation for excellence in teaching English skills as well as the nuances of U.S. academic culture assures that our students will have a better chance at success.”

“We are extremely pleased to welcome Marlboro College as the 12th partner in our University Pathways Program,” said ILI executive director Caroline Gear, who extolled Marlboro’s beautiful rural setting. “It is an ideal spot for international students seeking degrees in the United States from a very reputable college, and who also want to experience U.S. culture outside of large urban areas.”

ILI’s University Pathway Program includes a range of selected colleges and universities, each of which offers academic courses that are of interest to international students. Other partners include Bay Path University, Boston Architectural College, Elms College, Greenfield Community College, Lasell College, Paul Smith’s College, School for International Training, Springfield College, Western New England University, Westfield State University, and University of Massachusetts-Amherst Graduate School. Marlboro is the smallest partner institution, and as such shares many characteristics with ILI.

“We have a lot in common with ILI, in terms of our campus culture and educational philosophy, and this will be a very natural progression for many students coming to us from overseas,” says Maggie. “Not only does ILI provide international students with the kind of language training that can help them succeed in a challenging liberal arts curriculum, it also provides an introduction to the academic culture of an American college experience, which is so crucial for success here.”

Movies from Marlboro Takes On the Not-Too-Distant Future

“Wetware marks a departure for me,” says Marlboro film professor and director Jay Craven, referring to the most recent production of his Movies from Marlboro semester intensive. “My earlier films are all set in the past, working with Faulkner’s and T.S. Eliot’s ideas that ‘the past is always present.’ Now we’re looking to see, in our era of instant communication and a sometimes fading sense of history, whether the future is also present. Of course, it is.”

Marking the third Movies from Marlboro intensive, 24 professionals mentored and collaborated with 30 students from a dozen colleges to shoot Wetware last spring semester at three locations: Brattleboro and Burlington in Vermont, and Nantucket in Massachusetts. Now in postproduction, Wetware is scheduled for release this fall.

Based on the novel by Guggenheim Fellowship–winning writer Craig Nova, Wetware is set in a not-too-distant future where a cutting-edge genetic engineering firm alters clients to help them cope with the most reviled jobs. When a pair of experimental prototypes escape into a volatile and dangerous world, their creator scrambles to track them down and makes a provocative discovery that will change everything.

“We’re excited to be making this Vermont/Nantucket noir—our first production that splits locations between northern and southern New England,” says Jay. “The truth is that the place in this film is more fictional than any film I’ve made. This is one reason that our invented visual palette becomes so important. Yes, the uniqueness of Vermont towns and Nantucket streets and beaches will shine through, but our job here is to knit and blend and draw from natural assets that inform our own vision.”

The cast of Wetware includes a mix of Hollywood and Broadway veterans, emerging talent, and New England actors, starring Jerry O’Connell, Morgan Wolk, Cameron Scoggins, Bret Lada, Nicole Shalhoub, Garret Lee Hendricks, John Rothman, and Susan McGinnis. A professional crew worked with students from Wellesley College, University of California at Berkeley, Wesleyan University, Augsburg College, Mount Holyoke College, Sarah Lawrence College, University of Maine, Colby Sawyer College, Simmons College, Lyndon State College, Fitchburg State University, and of course Marlboro College.

Movies from Marlboro was established in 2012 and has produced two films to date, Northern Borders in 2012 and Peter and John in 2014. Inspired by pioneering Vermont educator John Dewey’s call for intensive learning that enlarges meaning “through shared experience and joint action,” the biennial program is unique in the nation. “Within the hyper-commercialized media industry, we work to combine transformative experiential learning, community engagement, and our best hope for sustainable place-based independent film production and regional release,” says Jay.

Campus Gets a Taste of “Real Food”

By Kristen Thompson ’18

In April 2014 former president Ellen McCulloch-Lovell and Benjamin Newcomb, then Marlboro’s chef manager, signed the Real Food Campus Commitment, making Marlboro’s dining services the first branch of Metz Culinary Management to take on the challenge (see Potash Hill, Fall 2014). Since then, the real struggle has been trying to meet the 20 percent “real food” quota by 2020.

The Real Food Challenge (RFC) is a national program with the goal of directing more than $1 billion of university money spent on food toward food that is “real” (ethically, locally, and/or healthily produced). Since signing on in 2014, Marlboro College has made strides in sourcing food from companies that treat their livestock better and give their employees fair wages and safe working conditions. This fall semester chemistry professor Todd Smith is introducing Searching for Food Justice, a class geared directly toward assessing the college’s food purchases based on “real food” criteria. But there are still challenges.

“We’ve established curricular support and have a working team in place within a committee on campus, but more work is needed to identify peer leaders and support their involvement with the RFC,” says Ben, now food services manager. “The new guidelines and criteria were recently updated; it’s time to launch the calculator and start using our updated Real Food Policy as part of that effort.”

Marlboro’s beverages exemplify the college’s efforts to invest in fair food. The dining hall and Potash Grill buy all of their coffee from Mocha Joe’s, which works directly with communities in Cameroon where coffee is grown. They pay the people working there fairly, and money goes back into the local communities, in some cases contributing to the building of churches and schools. Black River Produce is one of Marlboro’s key sources for humanely raised meat with neither hormones nor antibiotics, from the grass-fed burgers in the grill to the local bacon, and even some of the chicken served on campus.

“The dining staff are beginning work on a special local farm-to-table menu to facilitate more real, local, sustainable food than ever despite our budgetary challenges,” says Ben. “We recently rejoined Windham Farm and Food, sourcing 100 percent real food daily from over 84 hyper local farms with an aggregation and delivery service. The farmers are marketing directly to us, greatly improving our access to locally grown and produced items for our menus.”

Despite these significant gains, community involvement remains challenging—it has been difficult to make the Real Food Challenge enticing with so many other academic and extracurricular projects pursued by such a small school population. While efforts were made throughout the last spring semester to encourage students to get involved, the bulk of the work fell to a few individuals.

“In order to make the Real Food Challenge stronger on campus, we need more education for all involved,” says Brian Newcomb, Potash Grill manager. He asserts that if more of the Marlboro community knows about the Real Food Challenge, they may be able to point the kitchen staff to other “real” food sources. “The more they know, the more they can speak up. The more they speak up, the more we can instill change.”

Community Engagement at Pine Ridge

By Noah Strauss Jenkins ’18

Over spring break last April, photography professor John Willis and a group of students traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation, in South Dakota, a continuation of the close relationship John has maintained with the Oglala Lakota Sioux community there for 25 years. He says there has been a tendency for outsiders to come into the reservation with big promises that they never make good on, making the community wary, so the group focused on helping where they could and meeting people through that process.

Over spring break last April, photography professor John Willis and a group of students traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation, in South Dakota, a continuation of the close relationship John has maintained with the Oglala Lakota Sioux community there for 25 years. He says there has been a tendency for outsiders to come into the reservation with big promises that they never make good on, making the community wary, so the group focused on helping where they could and meeting people through that process.

“We met a lot of amazing people, and had a lot of amazing experiences that I believe were very eye-opening for everyone,” says John. “Marlboro students were doing collaborative community engagement, where you are there to work with the community, rather than just coming by and trying to save ‘people in need.’ They had a clear awareness that they would benefit from the experience more than those they went to work with, but did what they could to make it useful for all.”

“For me the trip was focused more on connecting with the people who live there, and learning about their lives and the challenges that come with living there,” says junior Chris Lamb, one of the six students who participated. “The history of how they were forced onto ‘the rez’ by whites was something that was always present in my mind. It was also about the beauty that still lives there, in their families and communities.”

The trip was designed to teach students about modes of service and Lakota culture, and to show that the culture on the reservation is very dynamic despite being one of the poorest communities in America. Students met with families and elders to talk about the politics surrounding their land, gender roles, and family traditions, and also had the opportunity to meet with spiritual leaders and participate in ceremonies.

“We loved being able to spend time with families in their homes, and having the opportunity to really try and see into their lives,” says junior Cait Mazzarela. “They were really open, and shared a lot about their beliefs and lives, and it’s amazing to be able to get an inside look.”

The students raised money to make the trip possible for each of them, regardless of their ability to pay, and had enough extra to donate funds to several programs they were involved with there. One of these is B.E.A.R. (Be Excited About Reading), an after-school program working with suicide prevention and giving youth better alternatives, including counseling efforts, academic help, sporting opportunities, and healthy snacks for youth. The students also assisted the tribal radio station with fundraising and helped the high school set up a student online newsletter, including buying three cameras for their use.

Another way the group decided to assist the B.E.A.R. project was through skateboarding, which has proven to be a respected alternative for youth on the reservation. The tribe has built an impressive skate park for this purpose, but most of the equipment they have available is poor quality. Marlboro College staff carpenter Brent Johnston used his connections in the skateboarding world to access quality equipment, at cost, from a manufacturer. The group purchased several sets of boards and helmets, aided by personal contributions from Brent, President Kevin Quigley, and Plant and Operations Director Dan Cotter.

In each case, the students responded directly to the needs that were presented, collaborating with a community that was still deeply immersed in their culture and tradition. “Underneath the struggles we hear about, there is a lot of resilience and pride in their traditional ways,” says John. “There are a lot of strong and motivated people trying to do good out there, trying to save their culture, a culture filled with beliefs and practices we all would benefit from understanding.”

Also of Note

“Although I will always look at the beauty of nature in my work, I also hope to reveal a truth beyond it,” says Hilary Baker, multimedia resource specialist. Hilary shared some her new work in a Drury Gallery show last February, called Water Reconnect, and then again at the grad school for “gallery walk” in June. Her work offers deeply layered images that integrate the alternative with the digital, exploring our multifaceted relationships with water. See more at studiohb-digitalarts.squarespace.com.

“Although I will always look at the beauty of nature in my work, I also hope to reveal a truth beyond it,” says Hilary Baker, multimedia resource specialist. Hilary shared some her new work in a Drury Gallery show last February, called Water Reconnect, and then again at the grad school for “gallery walk” in June. Her work offers deeply layered images that integrate the alternative with the digital, exploring our multifaceted relationships with water. See more at studiohb-digitalarts.squarespace.com.

An MBA student with a concentration in mission-driven organizations, Chris Meehan was selected for the prestigious Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Results Based Leadership Development program. Chris was one of 20 participants chosen nationally for the program, which includes seven two-day, in-person intensives all around the country. “The program will be focusing on our Collective Impact work in Vermont, which is a part of a larger pilot project of Feeding America called Collaborating for Clients (C4C),” says Chris, the chief community impact officer for the Vermont Foodbank.

In March, Felix Jarrar ’16 presented a paper at the Bowling Green State University Graduate Student Conference for composers, titled “‘Die Lorelei’: an examination of three versions of Liszt’s text setting of Heine.” Based on his Plan of Concentration work, Felix’s paper considers Franz Liszt’s settings of Heinrich Heine’s poem and how they revise and transform musical material, both melodically and harmonically. “This paper examines how the most interesting and significant musical aspects of Liszt’s text setting come at the expense of the poetic content,” says Felix.

In February, in recognition of Black History Month, Marlboro sponsored a “community read” of Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine. James Turpin ’16 led a discussion of the book-length poem about race and the imagination, which Rankine called an attempt to “pull lyric back into its realities.” According to The New Yorker, “Those realities include the acts of everyday racism—remarks, glances, implied judgments—that flourish in an environment where more explicit acts of discrimination have been outlawed.”

In February, in recognition of Black History Month, Marlboro sponsored a “community read” of Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine. James Turpin ’16 led a discussion of the book-length poem about race and the imagination, which Rankine called an attempt to “pull lyric back into its realities.” According to The New Yorker, “Those realities include the acts of everyday racism—remarks, glances, implied judgments—that flourish in an environment where more explicit acts of discrimination have been outlawed.”

In June, Hillary Orsini (formerly Hillary Boone) shared her experience with results-based accountability (RBA) and nongovernment organizations in Vermont at Measurable Impact 2016, an RBA conference in Baltimore. This national conference was a unique opportunity for public and social sector leaders to explore the concepts and tools their peers around the world are using to improve performance and achieve community impact. The assistant director of the Center for New Leadership, Hillary has trained and coached hundreds of organizations across New England in the use of RBA.

Alumni have long known that when it comes to learning in a tight-knit classroom with fully engaged faculty, Marlboro College is second to none. In April, Marlboro was ranked number one for the lowest student-faculty ratio, coming in at 5-to-1, by U.S. News & World Report. It shared the list with 20 other colleges including such top-rated liberal arts schools as Williams, Amherst, Swarthmore, and Skidmore. Marlboro also had the lowest total undergraduate enrollment among the schools listed. Learn more.

In June, dining hall manager Ben Newcomb was presented with an exemplary service award at the Metz Culinary Management leadership conference. “Ben was chosen for this award because he exemplifies the values Metz represents,” says Cheryl McCann, vice president for human resources at Metz. “We feel as though Ben takes these values and translates them to action.” In addition to receiving a cash prize and engraved award, Ben is most excited about being selected to attend a three-day workshop in October that includes culinary training in Mediterranean and Latin cuisines with an award-winning chef.

The graduate and professional studies program introduced three new awards to attract the very best candidates: the Greater Good Award, recognizing students who have demonstrated a commitment to community through national service; the John Dewey Award, recognizing students who have served others through engaged teaching; and the Whetstone Fellowship, recognizing alumni of the undergraduate program. The fellowship acknowledges that Marlboro alumni are ideally suited to continue their education at the graduate school, where they will find a familiar focus on community, self-directed learning, and project-based work.

Town Meeting, on March 30, passed a resolution to support the designation of approximately 136 acres of Marlboro College’s forested lands north of campus as an ecological reserve. “It is the opinion of the Town Meeting that these lands will be a rare and valuable location for education and ecological research, an important forested area in a time of climate change, a unique college asset that will attract and retain community members, and perhaps most importantly, a haven for the community—its human and non-human members alike.” The language charged the Environmental Advisory Committee with presenting a detailed proposal to the Town Meeting and trustees by the end of 2016.

“Marlboro College parallels many of my values and beliefs in higher education,” says Luis Rosa, who joined the college in January as dean of students. “Although the college maintains a rigorous curriculum, there is a great effort to ensure a broad range of access to students.” Luis has 15 years of experience in student affairs leadership and administration, most recently as dean of community life at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and brings a style of leadership that is democratic and participatory, in keeping with Marlboro’s longstanding ideals.

The Distinguished Service Award for staff members in the spring semester went to two essential staff: Cheri Morris, housecleaning staff member for the undergraduate campus, and Mike Hutchins, maintenance staff member for the graduate campus. According to Cheri’s nomination, she “cleans like hell” and “we really appreciate the effort she puts into her work, and that she takes the time to be part of our community life.” Mike’s nomination says he has “taken upon himself to find, cultivate, and distribute flowering plants throughout the grad area.” Congratulations, Cheri and Mike.

Last March, five staff from Marlboro College Graduate and Professional Studies were chosen to present at the 2016 Women’s Leadership Conference, a two-day event sponsored by Vermont Women in Higher Education, in Killington, Vermont. Their participation raises Marlboro’s profile as an innovator for leadership development in the state. Marlboro staff presenters included: Kathy Urffer, associate registrar for graduate and professional studies; Julie Van der Horst Jansen, business manager for the Center for New Leadership (CNL); Beth Neher, capstone coordinator; Kim Lier, teaching and learning specialist for CNL; and Hillary Orsini, assistant director of CNL.

Polar Plunge

In March, 17 stalwart individuals experienced the “penultimate purification rite of passage on Potash Hill,” according to OP director Randy Knaggs (pictured).

Dance Fever

Kristen Thompson ’18, Karissa Wolivar ’19, Erin Huang-Shaffer ’18, Liana Nuse ’16, dance teacher Khady Malal Badji, Lucy Hammond ’18, and Cait Mazzarella ’18 prepare for a dance party/performance during a journey to Senegal in June, the culmination of a class called Dance in World Cultures. See a short video clip.

Sex Positive

Total Health Center office manager Celena Romo ’05 and student life coordinator Alison Trimmer mix it up in a game of “Consensual Twister” during a Sex Positivity Resource Fair in February, part of a month of activities focused on sex positivity.

Big Apple Art

Sabrina Konick ’19 and Trevor Asbury ’17 listen to visual arts faculty member Tim Segar at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during an action-packed weekend visit to New York art museums in April.

Tough Mudders

Cat Clauss ’17 crosses a rope bridge during a “mud run” all around campus in April, enjoyed by students, community members, and several participants from local Girls on the Run programs.

Events

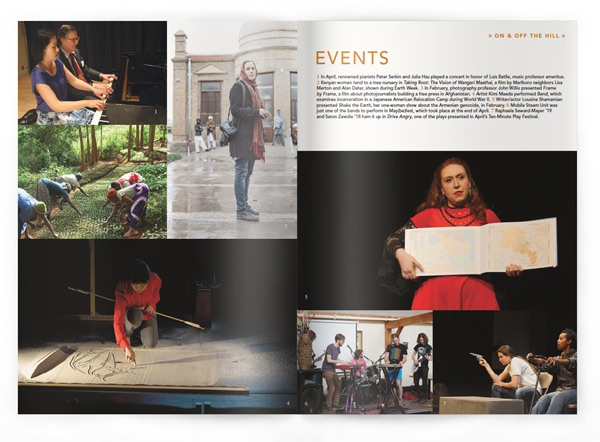

1 In April, renowned pianists Peter Serkin and Julia Hsu played a concert in honor of Luis Batlle, music professor emeritus. 2 Kenyan women tend to a tree nursery in Taking Root: The Vision of Wangari Maathai, a film by Marlboro neighbors Lisa Merton and Alan Dater, shown during Earth Week. 3 In February, photography professor John Willis presented Frame by Frame, a film about photojournalists building a free press in Afghanistan. 4 Artist Kimi Maeda performed Bend, which examines incarceration in a Japanese American Relocation Camp during World War II. 5 Writer/actor Lousine Shamamian presented Shake the Earth, her one-woman show about the Armenian genocide, in February. 6 Mobile Steam Unit was just one of the bands to perform in May(be)fest, which took place at the end of April. 7 Raphaela Seward-Mayer ’19 and Saron Zewdie ’18 ham it up in Drive Angry, one of the plays presented in April’s Ten-Minute Play Festival.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

Sophomore Noah Strauss Jenkins sat down with biology and environmental studies professor Jenny Ramstetter last February to discuss climate change, statistics, forest reserves, and the Afromontane vegetation of Ethiopia. You can read the whole interview.