Spring 2017

Editor’s Note

“Oh, what sad times are these when passing ruffians can say ‘Ni’ at will to old ladies,” said Ian Bates ’19, a.k.a. Roger the Shrubber, in last fall’s production of Marlboro College and the Holy Grail (see Events). “There is a pestilence upon this land; nothing is sacred. Even those who arrange and design shrubberies are under considerable economic stress at this point in time.”

“Oh, what sad times are these when passing ruffians can say ‘Ni’ at will to old ladies,” said Ian Bates ’19, a.k.a. Roger the Shrubber, in last fall’s production of Marlboro College and the Holy Grail (see Events). “There is a pestilence upon this land; nothing is sacred. Even those who arrange and design shrubberies are under considerable economic stress at this point in time.”

Times are indeed dark and divisive, and one would be excused for perceiving a certain melancholy in this issue of Potash Hill, from Sophie Gorjance’s peek into dystopian linguistics to Marcus DeSieno’s disconcertingly stark and beautiful landscapes. Morgan Ingalls’ account of researching nocturnal, cave-loving, snaggletooth mammals threatened by a mysterious plague could be construed as positively gothic in its darkness, but there is another side to these stories, of course.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “When it is dark enough, you can see the stars.” It often takes a step into the unfamiliar to make new discoveries, gain new perspectives, touch the ineffable. That’s true whether the path leads to post-apocalyptic fiction, surveillance technology, or dank, claustrophobic caves. Or long, snowy winters at a tiny college on a hill, for that matter.

In this period of uncertainty, nationally and around the world, I am grateful to be part of a strong campus community that strives for honest, creative inquiry, one that is open to diverse thoughts, races, religions, and backgrounds. In recent months Marlboro College has redoubled its commitment to diversity and inclusion, including a new task force on making the college a safe and welcoming place for international students. Like other community members, I value the college’s founding principles of democracy and its practices that promote citizen engagement and global perspective.

I welcome your diverse thoughts on this issue of Potash Hill, or on the place of Marlboro College in an uncertain world. What did you discover at Marlboro, and where did that lead you? Share your perspective with us at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

—Philip Johansson

a.k.a. Boat-keeper at the Castle Aargh (see photo)

Inside Front cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the undergraduate campus was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Ella McIntosh

Staff Photographers: David Teter ’19 and Michael Jung ’17

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

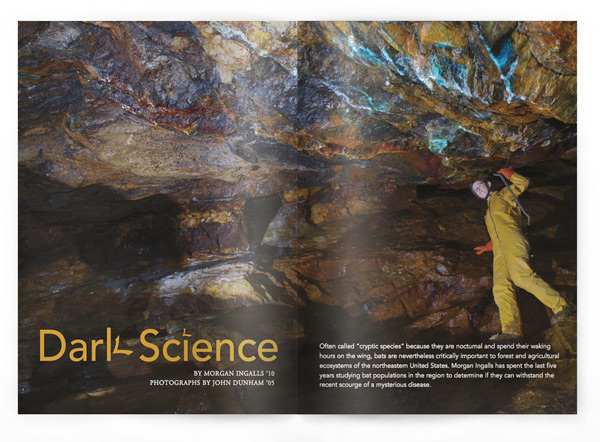

Front Cover: A caver pauses on the brink of a recently discovered Vermont cave, perhaps the winter home of federally threatened long-eared bats or other bat species. Morgan Ingalls has been spelunking her way across New England to get to know these cryptic species better (see her article). Photo by John Dunham

Front Cover: A caver pauses on the brink of a recently discovered Vermont cave, perhaps the winter home of federally threatened long-eared bats or other bat species. Morgan Ingalls has been spelunking her way across New England to get to know these cryptic species better (see her article). Photo by John Dunham

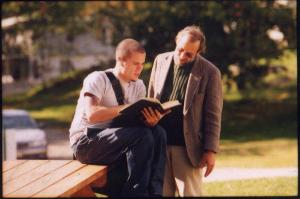

“I think this college has been a perfect fit for the kind of education I’ve been wanting to pursue,” said freshman Eric Wefeld (pictured, right) at a Town Meeting last November. His comments on gratitude were part of a series of “First Year Voices,” reflections by new students on life at Marlboro. See Eric.

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, both undergraduate and graduate students engage in deep exploration of their interests—and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

Up Front

New Outlook

When I climb to the top of a tree, where I could reach up and touch the highest needles, I leave the stress of schoolwork, social insecurities, worries, and fears far below. For a moment I am free to look at my life, my community, the world from a different perspective.

—Clayton Clemetson ’18

Photo by Clayton Clemetson

Clear Writing

Dystopian Language

By Sophie Gorjance ’16

Part of the beauty of post-apocalyptic and dystopian fiction lies in the fact that after the authors have destroyed whatever world originally existed in their stories, they are able to rebuild that world in whatever shape they like. One aspect of writing an apocalypse that authors frequently overlook is that of language.

Dystopian books that discuss the ways their environment or government has shaped the language, like 1984, The Dispossessed, and The Time Machine, are often praised and become classics. It takes a rare story to actually involve that new language and rise to an equivalent level of success, as was the case with A Clockwork Orange. It seems that Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic novel published in 1980, got too close to the invisible line at which the effort required is more than most readers are willing to expend. Yet those who do cross that line find a rich, nuanced world embedded within the language.

Riddley Walker’s world is objectively changed from our own: difficult, dangerous, and rife with lore. The language Hoban invented works on many levels to communicate a culture based on oral storytelling, where there are much more pressing daily concerns than spelling homophones, where very few people read or write anyway. Without having to say so directly, Hoban shows readers how Riddley’s society has descended from ours, and how it has retained only broken scraps of words with no concrete meaning. “Sarvering gallack seas” bears only passing resemblance to “sovereign galaxies” yet the people in Riddley’s world chant it as part of their funeral rites.

Despite all the intrigue, mystery, and general awesomeness Hoban packs into Riddley Walker, it never attained the fame or staying power of A Clockwork Orange. The reason for this, I believe, is that Hoban did his work too well. But all it takes is a few pages of effort before the reader slides into “Riddleyspeak” like putting on a glove. The outermost layer of your hand isn’t your skin anymore, and the outermost layer of your mind is running with dogs 2,000-odd years in an imagined future, but it fits just perfectly.

Sophie Gorjance completed a Plan in writing, and this excerpt is adapted from her Plan paper, “Riddleyspeak: Post-Apocalyptic Shifts in Language.” You can find excerpts of other Plans, and watch Sophie reading from her post-apocalyptic novella Under New Stars, in the Virtual Plan Room.

Photo by David Teter

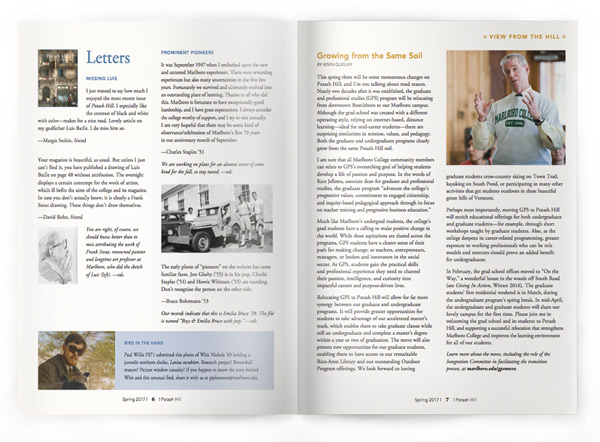

Letters

Missing Luis  I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed the most recent issue of Potash Hill. I especially like the contrast of black and white with color—makes for a nice read. Lovely article on my godfather Luis Batlle. I do miss him so.

I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed the most recent issue of Potash Hill. I especially like the contrast of black and white with color—makes for a nice read. Lovely article on my godfather Luis Batlle. I do miss him so.

—Margie Serkin, friend

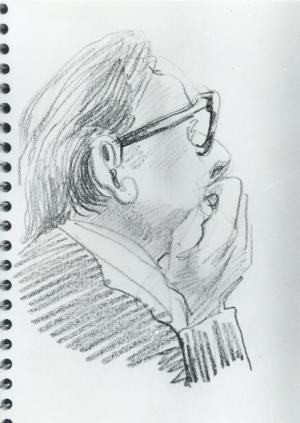

Your magazine is beautiful, as usual. But unless I just can’t find it, you have published a drawing of Luis Batlle on page 48 without attribution. The oversight displays a certain contempt for the work of artists, which ill befits the aims of the college and its magazine. In case you don’t actually know, it is clearly a Frank Stout drawing. These things don’t draw themselves.

—David Rohn, friend

You are right, of course, we should know better than to miss attributing the work of Frank Stout, renowned painter and longtime art professor at Marlboro, who did the sketch of Luis (right). —eds.

Prominent Pioneers

It was September 1947 when I embarked upon the new and untested Marlboro experiment. There were rewarding experiences but also many uncertainties in the first few years. Fortunately we survived and ultimately evolved into an outstanding place of learning. Thanks to all who did this. Marlboro is fortunate to have exceptionally good leadership, and I have great expectations. I always consider the college worthy of support, and I try to visit annually. I am very hopeful that there may be some kind of observance/celebration of Marlboro’s first 70 years in our anniversary month of September.

—Charles Staples ’51

We are working on plans for an alumni event of some kind for the fall, so stay tuned. —eds.

The early photo of “pioneers” on the website (right) has some familiar faces. Jon Glasby (’55) is in his jeep, Charlie Staples (’51) and Howie Whittum (’55) are standing. Don’t recognize the person on the other side.

The early photo of “pioneers” on the website (right) has some familiar faces. Jon Glasby (’55) is in his jeep, Charlie Staples (’51) and Howie Whittum (’55) are standing. Don’t recognize the person on the other side.

—Bruce Bohrmann ’53

Our records indicate that this is Emilia Bruce ’58. The file is named “Boys & Emilia Bruce with jeep.” —eds.

Bird in the Hand  Paul Willis FS71 submitted this photo (right) of Whit Nichols ’69 holding a juvenile northern shrike, Lanius excubitor. Research project? Broomball mascot? Picture window casualty? If you happen to know the story behind Whit and this unusual find, share it with us at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

Paul Willis FS71 submitted this photo (right) of Whit Nichols ’69 holding a juvenile northern shrike, Lanius excubitor. Research project? Broomball mascot? Picture window casualty? If you happen to know the story behind Whit and this unusual find, share it with us at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

View from the Hill

Growing from the Same Soil

By Kevin Quigley

This spring there will be some momentous changes on Potash Hill, and I’m not talking about mud season. Nearly two decades after it was established, the graduate and professional studies (GPS) program will be relocating from downtown Brattleboro to our Marlboro campus. Although the grad school was created with a different operating style, relying on internet-based, distance learning—ideal for mid-career students—there are surprising similarities in mission, values, and pedagogy. Both the graduate and undergraduate programs clearly grow from the same Potash Hill soil.

This spring there will be some momentous changes on Potash Hill, and I’m not talking about mud season. Nearly two decades after it was established, the graduate and professional studies (GPS) program will be relocating from downtown Brattleboro to our Marlboro campus. Although the grad school was created with a different operating style, relying on internet-based, distance learning—ideal for mid-career students—there are surprising similarities in mission, values, and pedagogy. Both the graduate and undergraduate programs clearly grow from the same Potash Hill soil.

I am sure that all Marlboro College community members can relate to GPS’s overarching goal of helping students develop a life of passion and purpose. In the words of Kate Jellema, associate dean for graduate and professional studies, the graduate program “advances the college’s progressive values, commitment to engaged citizenship, and inquiry-based pedagogical approach through its focus on teacher training and progressive business education.”

Much like Marlboro’s undergrad students, the college’s grad students have a calling to make positive change in the world. While these aspirations are shared across the programs, GPS students have a clearer sense of their path for making change: as teachers, entrepreneurs, managers, or leaders and innovators in the social sector. At GPS, students gain the practical skills and professional experience they need to channel their passion, intelligence, and curiosity into impactful careers and purpose-driven lives.

Relocating GPS to Potash Hill will allow for far more synergy between our graduate and undergraduate programs. It will provide greater opportunities for students to take advantage of our accelerated master’s track, which enables them to take graduate classes while still an undergraduate and complete a master’s degree within a year or two of graduation. The move will also present new opportunities for our graduate students, enabling them to have access to our remarkable Rice-Aron Library and our outstanding Outdoor Program offerings. We look forward to having graduate students cross-country skiing on Town Trail, kayaking on South Pond, or participating in many other activities that get students outdoors in these beautiful green hills of Vermont.

Perhaps most importantly, moving GPS to Potash Hill will enrich educational offerings for both undergraduate and graduate students—for example, through short workshops taught by graduate students. Also, as the college deepens its career-related programming, greater exposure to working professionals who can be role models and mentors should prove an added benefit for undergraduates.

In February, the grad school offices moved to “On the Way,” a wonderful house in the woods off South Road (see Giving In Action, Winter 2016). The graduate students’ first residential weekend is in March, during the undergraduate program’s spring break. In mid-April, the undergraduate and graduate students will share our lovely campus for the first time. Please join me in welcoming the grad school and its students to Potash Hill, and supporting a successful relocation that strengthens Marlboro College and improves the learning environment for all of our students.

Learn more about the move, including the role of the Integration Committee in facilitating the transition process, at marlboro.edu/gpsmove.

Dark Science

By Morgan Ingalls ’10

Photographs by John Dunham ’05

Often called “cryptic species” because they are nocturnal and spend their waking hours on the wing, bats are nevertheless critically important to forest and agricultural ecosystems of the northeastern United States. Morgan Ingalls has spent the last five years studying bat populations in the region to determine if they can withstand the recent scourge of a mysterious disease.

It’s mid-January in southwestern Vermont and, with the blustery windchill, the high for the day won’t make it out of the single digits. I’m helping the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department conduct a winter hibernacula survey—in other words, I’m going to spend the day in a cave, counting bats. I’m joined by two friends, both experienced cavers, and a technician from the state agency. The cave we’re headed to is about a mile up a steep mountainside, and the ground is covered by ice and a thin layer of powdery snow, but together we claw our way to the cave entrance.

It’s a relief to get out of the wind and into the relative warmth of the 42-degree cave. Caves are the same temperature year round, making them perfect places for bats to hibernate. Vermont bat species that don’t migrate south for the winter spend the early autumn fattening up on insects, then in late October they find a cave and settle down for the winter. By dropping their body temperature to within a few degrees of the ambient temperature, they can hibernate until the insect populations return in the spring and they can have another meal.

To survive the winter by hibernating, bats have to slow down their entire physiology to conserve energy. Their heartbeats decrease from a brisk 400 beats per minute to 25 beats per minute. They also have to slow down their immune systems, which leaves them vulnerable to infection. This has recently become a major problem for bats in the eastern United States as more and more of them succumb to white-nose syndrome (WNS), one of the primary reasons for my visit to this Vermont cave.

WNS is a fungal infection that attacks the face, ears, and wing membranes of bats while they hibernate. The syndrome was first seen in the Albany, New York, area in the winter of 2006, and has since spread to 29 states (including Vermont) and five Canadian provinces. While scientists are still not sure exactly how WNS kills bats, it is believed that the disease causes bats to stir from hibernation more often, which quickly drains their fat reserves. This means that many bats die from starvation and dehydration over the winter. Those bats that do make it through to spring continue to face challenges, as damage to their wing membranes leaves some unable to fly for their first meal in five months.

About 50 feet into the cave we see our first bat. It turns out to be an exciting find: a northern long-eared bat. While northern long-eared bats used to be abundant throughout the northeast, their populations have declined so drastically due to WNS that they were recently listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

As we continue through the cave, we see three other species: little brown bats, big brown bats, and eastern small-footed bats. All three of these species have suffered population declines of varying extent due to WNS. When we climb back out of the cave after six hours underground, we’ve counted 19 bats. Ten years ago, 19 bats would hardly be worth reporting, but now, post-WNS, it’s a pretty good day.

When bats emerge from hibernation in the spring, the females move to maternity colonies where they’ll spend the next few months giving birth and caring for their pups. The maternity colonies can be up to 300 miles from their hibernation site, and females will return to the same colony year after year. Males also migrate away from the hibernation site, to foraging areas where they’ll spend the summer alone or with a few other males in “bachelor colonies.” Once juveniles are old enough to fly, males and females form fall “swarms” at cave and mine entrances, where they’ll mate and bulk up on fat for the hibernation season.

•••

Now it’s July on the coast of Maine and I’m at Acadia National Park, tracking female eastern small-footed bats in order to find maternity colonies. My team and I have been capturing bats using mist-nets: very fine nets that we place across travel corridors such as roads and trails. We open the nets around sunset and sit nearby battling the mosquitos, reading, playing cards, and checking the net every 10 minutes to see if we’ve captured a bat.

It’s my turn to check the net, and I can see when I get close enough that we’ve caught both one large and one small bat. I pull on nitrile gloves and gently grab the smaller bat. Untangling bats from mist-nets can be pretty tricky and requires a delicate touch, but also speed. Bats can become stressed if left for too long, so we try to minimize the time a bat is stuck in the net. I remove the strands of net one at a time from the bats’ feet and wings.

I bring both bats back to a camp table where we can collect some data. My co-worker, Carl, gets out a data sheet and records data while I get the smaller bat—an eastern small-footed bat—out of the paper bag it has been held in. This bat is a lactating female, which makes her of particular interest to us, since she could lead us back to a maternity colony. We also measure her forearm— the longest bone in the wing—and her ears. Then we put her in a small envelope and weigh her. She weighs about six grams, or very slightly more than a U.S. quarter. Finally, we use a small light to backlight the wings and determine how scarred they are from WNS damage.

This bat appears to be quite healthy, and we decide she’s a good candidate to track using radio-telemetry. To do this we affix a transmitter to the animal, a device that beeps on a specific radio frequency that can be detected using a receiver. The transmitters we’re using are some of the smallest available, slightly smaller than half a peanut, with a thin flexible antenna attached to one end. Altogether, the transmitters weigh about 0.3 grams, or about as much as four grains of rice.

Carl holds the bat with its wings and head down, exposing the bat’s back. Using small nail scissors, I give the bat a tiny haircut between the shoulder blades. I then put a dab of glue on the transmitter and position it onto the bald spot so the antenna runs down the bat’s back and off its tail. We put the bat back in a paper bag for 10 to 15 minutes to allow the glue to set, then release it back into the night. The transmitter battery and the glue will last three to four weeks. During that time we’ll be able to track the bat as it moves across the landscape.

The morning after we’ve trapped our female eastern small-footed bat, Carl and I drive around the park, listening for the beeps on the receiver that will indicate that we’re close to the animal. After two hours of driving, we finally pick up the signal of our bat. Using a directional antenna, we determine that the bat is roosting in a rocky area on the side of a mountain. We hike through the woods, scramble up outcrops, and finally locate our bat roosting deep in a crack on a sunny granite ledge. While we can’t actually see her, the signal from her transmitter assures us she is there.

That evening, to find out if our bat has led us to a maternity colony, we hike back up to the ledge a half hour before sunset. We find a spot where the sky will backlight any emerging bats, and settle in to count. Just before sunset, we see a bat emerge, but we know it isn’t our bat since the signal on the receiver tells us she’s still in the same location. In the next 15 minutes we see six more bats emerge, including ours. We can tell when she’s left because the signal on the receiver slowly fades as she flies away from us, off into the night.

While seven bats does not make for a large maternity colony (some other species form maternity colonies in the hundreds or even thousands), this maternity colony is a good size for this species in this region. Over the next few weeks we’ll continue to track this individual, as well as others, collecting more information about how these bats use the landscape.

In addition to being important for the natural environment, bats provide a number of ecosystem services to humans. Along with reducing the number of biting insects, bats are responsible for an estimated savings of $22.9 billion per year for the agricultural industry in the United States through pest reduction. While WNS has been devastating for bat populations, it has brought much-needed funding to bat research. Unfortunately, it may be too little, too late. Since bats reproduce at a very slow rate (for most species in the northeast, females give birth to one pup per year), building populations back to pre-WNS numbers may take hundreds of years. For some species, such as the federally listed northern long-eared bat, populations may already be too small to recover.

However, bat populations in New York and New England do show some signs of recovery. Population estimates based on winter hibernacula surveys are no longer dropping, but starting to plateau. This makes some researchers hopeful that we’ll soon start to see populations increase. While recovery from WNS will take a long time, the work researchers are doing to better understand bats and how they use the landscape can lead to more effective conservation measures, which might save some species.

After I’ve finished tracking my bats around Acadia National Park, I return to Vermont for the winter. Late fall is a slow time of year for bats and bat biologists. Bats are done with their fall swarm and settled for a long hibernation. Biologists sit in their warm homes and write up reports from the summer field season. However, come January, emails start flying and trips are planned for winter hibernacula counts. Soon, I’ll be squeezing into another cave entrance to go count some bats.

Morgan Ingalls graduated from Marlboro in 2010 with a Plan in biochemistry, including a study of white-nose syndrome and population decline in bats. Morgan has worked for Biodiversity Research Institute doing summer and fall bat habitat surveys for federal agencies, and has regularly helped regional state agencies with winter bat surveys. John Dunham runs the writing center at Antioch University New England. He is also a leader of Outdoor Program caving excursions and current president of the Vermont Cavers Association.

Graphic Animal Behavior

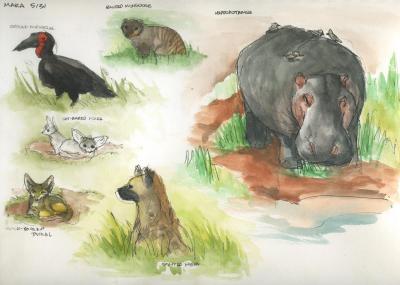

“I think spotted hyenas are really beautiful, in their own ghoulish way—I love their odd proportions,” says senior Nellie Booth, who is doing their Plan of Concentration in biology and visual arts. They spent two and a half weeks in Kenya last summer, touring Masai Mara, Samburu, and Lake Nakuru national parks and doing wildlife observations and field sketches, the basis for a narrative graphic novella about spotted hyena behavior. “I call it animal behavior fiction,” Nellie says of their biologically accurate book, titled Queen of the Mara. They are also exploring animal behavior and emotion through research on ravens; an exhibit of sculptures exploring themes of nature, birth, and death; and an educational card game about evolutionary adaptation. “I’m interested in connections between humans and nonhuman animals, including enrichment for captive animals.”

“I think spotted hyenas are really beautiful, in their own ghoulish way—I love their odd proportions,” says senior Nellie Booth, who is doing their Plan of Concentration in biology and visual arts. They spent two and a half weeks in Kenya last summer, touring Masai Mara, Samburu, and Lake Nakuru national parks and doing wildlife observations and field sketches, the basis for a narrative graphic novella about spotted hyena behavior. “I call it animal behavior fiction,” Nellie says of their biologically accurate book, titled Queen of the Mara. They are also exploring animal behavior and emotion through research on ravens; an exhibit of sculptures exploring themes of nature, birth, and death; and an educational card game about evolutionary adaptation. “I’m interested in connections between humans and nonhuman animals, including enrichment for captive animals.”

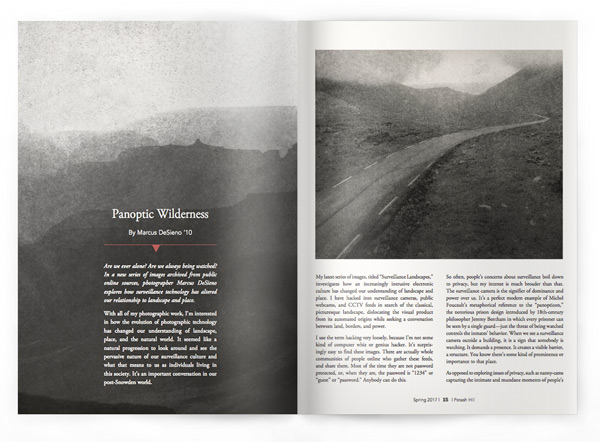

Panoptic Wilderness

By Marcus DeSieno ’10

Are we ever alone? Are we always being watched? In a new series of images archived from public online sources, photographer Marcus DeSieno explores how surveillance technology has altered our relationship to landscape and place. With all of my photographic work, I’m interested in how the evolution of photographic technology has changed our understanding of landscape, place, and the natural world. It seemed like a natural progression to look around and see the pervasive nature of our surveillance culture and what that means to us as individuals living in this society. It’s an important conversation in our post-Snowden world.

My latest series of images, titled “Surveillance Landscapes,” investigates how an increasingly intrusive electronic culture has changed our understanding of landscape and place. I have hacked into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in search of the classical, picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while seeking a conversation between land, borders, and power.

My latest series of images, titled “Surveillance Landscapes,” investigates how an increasingly intrusive electronic culture has changed our understanding of landscape and place. I have hacked into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in search of the classical, picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while seeking a conversation between land, borders, and power.

I use the term hacking very loosely, because I’m not some kind of computer whiz or genius hacker. It’s surprisingly easy to find these images. There are actually whole communities of people online who gather these feeds, and share them. Most of the time they are not password protected, or, when they are, the password is “1234” or “guest” or “password.” Anybody can do this.

So often, people’s concerns about surveillance boil down to privacy, but my interest is much broader than that. The surveillance camera is the signifier of dominance and power over us. It’s a perfect modern example of Michel Foucault’s metaphorical reference to the “panopticon,” the notorious prison design introduced by 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham in which every prisoner can be seen by a single guard—just the threat of being watched controls the inmates’ behavior. When we see a surveillance camera outside a building, it is a sign that somebody is watching. It demands a presence. It creates a visible barrier, a structure. You know there’s some kind of prominence or importance to that place.

As opposed to exploring issues of privacy, such as nanny-cams capturing the intimate and mundane moments of people’s lives, it seemed more interesting to me to look out at landscapes that were devoid of humans. The melancholic images that I’m assembling speak to how this technology shapes our understanding of place, and evoke conversations around power and ownership. That really intrigues me: why, on this road in the middle of nowhere, Kansas, is there a surveillance camera? Some of the locations, such as those in national parks, have a certain prominence or significance. But most of the places I stumble upon have no rhyme or reason. Maybe it’s a traffic camera; maybe it’s a weather camera. This technology is used for a variety of purposes besides the nefarious, but it certainly shapes our psyche when we see these things.

As opposed to exploring issues of privacy, such as nanny-cams capturing the intimate and mundane moments of people’s lives, it seemed more interesting to me to look out at landscapes that were devoid of humans. The melancholic images that I’m assembling speak to how this technology shapes our understanding of place, and evoke conversations around power and ownership. That really intrigues me: why, on this road in the middle of nowhere, Kansas, is there a surveillance camera? Some of the locations, such as those in national parks, have a certain prominence or significance. But most of the places I stumble upon have no rhyme or reason. Maybe it’s a traffic camera; maybe it’s a weather camera. This technology is used for a variety of purposes besides the nefarious, but it certainly shapes our psyche when we see these things.

A lot of this work is about being an archivist, having a selection process, trying to find those moments that present a heightened emotional state, or aesthetic moments that interest me. Essentially, I’m a curator of the surveillance internet. I find this really intriguing because I’m not only thinking about the nature of the technology, but of another layer—the ways in which I’m using the internet to construct this work. I deflate this idea of the artist as genius by using what’s available to me, what’s available to anybody.

I don’t alter the images, other than converting the ones in color to black and white. I like the starkness of the monochromatic image, which perhaps heightens the sense of drama. Black and white dislocates the landscape, so the identifiers of place are more limited. Much of the time I specifically seek out imagery that’s in soft focus, that has an impressionistic feel, that might have raindrops on the lens. I’m interested in cameras that might be grimy, and haven’t been serviced for a while—in finding imagery that abstracts the landscape in some way, that can speak to a history of landscape painting as well. It’s just another layer to this work, another vector in the history of how we perceive the landscape.

I don’t alter the images, other than converting the ones in color to black and white. I like the starkness of the monochromatic image, which perhaps heightens the sense of drama. Black and white dislocates the landscape, so the identifiers of place are more limited. Much of the time I specifically seek out imagery that’s in soft focus, that has an impressionistic feel, that might have raindrops on the lens. I’m interested in cameras that might be grimy, and haven’t been serviced for a while—in finding imagery that abstracts the landscape in some way, that can speak to a history of landscape painting as well. It’s just another layer to this work, another vector in the history of how we perceive the landscape.

Through these empty landscapes I want to create a contemplative state of mind. When my viewer looks at the images—when they’re taken into these landscapes— they can reflect on their own relationship to surveillance technology and how it’s affected them, whether they know it or not. The very act of someone surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated, melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno received his MFA in studio art from the University of South Florida, and is currently a visiting photography professor at Marlboro. Marcus’s work has been exhibited nationally and featured in a variety of publications, from Smithsonian to Wired. In August, his “Surveillance Landscapes” series was selected for Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50, a juried competition for emerging photographers, for pushing the boundaries of the medium. This has led to a book deal with Daylight, a nonprofit publisher of fine art and photography books.

Corrupted Video Files

“The videos of David Hall were meant to take the viewer out of the conventional televisual experience,” says senior Ian Grant, referring to the artist who introduced “TV Interruptions” on Scottish television in the 1970s. “Much like Hall, my own work will often critique the culture of mainstream media, and creates an aesthetic with this in mind.” Ian is completing his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, with a written portion on British video art in the 70s and 80s and an exhibit of photographs, video art, and video installation. “My work often involves a new art form called ‘glitch art,’ which causes the viewer to question their experience.” An example of this (left) shows a still from corrupted video files Ian took during the anti-Trump protest in New York City the night after the election.

“The videos of David Hall were meant to take the viewer out of the conventional televisual experience,” says senior Ian Grant, referring to the artist who introduced “TV Interruptions” on Scottish television in the 1970s. “Much like Hall, my own work will often critique the culture of mainstream media, and creates an aesthetic with this in mind.” Ian is completing his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, with a written portion on British video art in the 70s and 80s and an exhibit of photographs, video art, and video installation. “My work often involves a new art form called ‘glitch art,’ which causes the viewer to question their experience.” An example of this (left) shows a still from corrupted video files Ian took during the anti-Trump protest in New York City the night after the election.

On and Off the Hill

New Students Build Community Skills

Marlboro College has always valued and prioritized community, as supported by its intentionally small size, informal setting, and shared governance model. Yet there has been a growing sense among the faculty that the college could be more explicit about giving students the skills and experiences to help them thrive in the Marlboro community. A new course called Common Ground: Living and Working in Community, piloted last fall, stems from recent faculty discussions looking critically at the curriculum (Potash Hill, Fall 2016).

“Part of the inspiration is the potential of Marlboro College, because of its history and small size, to be a laboratory for community building and conflict resolution,” says Kate Ratcliff, professor of American studies and gender studies. “The questions at the heart of this course are crucial ones for our democracy and our planet. How do we work together to create a better world? How do we recognize the dynamics of power and privilege that are at play and create more inclusive community spaces? How do we address differences and resolve conflicts?”

“Part of the inspiration is the potential of Marlboro College, because of its history and small size, to be a laboratory for community building and conflict resolution,” says Kate Ratcliff, professor of American studies and gender studies. “The questions at the heart of this course are crucial ones for our democracy and our planet. How do we work together to create a better world? How do we recognize the dynamics of power and privilege that are at play and create more inclusive community spaces? How do we address differences and resolve conflicts?”

Kate co-taught Common Ground along with Jean O’Hara (theater, environmental studies, and gender studies) and Seth Harter (Asian studies and history). The three faculty members designed the course in collaboration with former head selectperson and senior Solomon Botwick-Ries, with additional guidance from graduate school faculty members Pat Daniels and Lori Hanau.

“We distributed surveys to students at Town Meeting and during lunch so their ideas could shape the course we were imagining,” says Jean. “Students chose collaboration, communication, and creative thinking as the three most important skills that would help new students to succeed. Marlboro College does an excellent job mentoring students to seek their individual passions and pursue deep inquiry through Plan, but this course was created to help our students live, learn, and govern in a tight-knit community, which takes a different set of skills.”

In Common Ground, students investigated community through both theory and practice, starting with examining their own strengths and perspectives and then exploring their relationships to others. Building on reading and writing assignments to provide context and analysis, they looked critically at the Marlboro College community and learned tools for community building. The syllabus also included a degree of malleability, to respond to events in the community as they occurred.

In Common Ground, students investigated community through both theory and practice, starting with examining their own strengths and perspectives and then exploring their relationships to others. Building on reading and writing assignments to provide context and analysis, they looked critically at the Marlboro College community and learned tools for community building. The syllabus also included a degree of malleability, to respond to events in the community as they occurred.

“Every semester, something gets lobbed into the community from an unforeseeable place and disrupts the work in classes,” says Seth. “I was gnashing my teeth thinking about the presidential election, then a Title IX controversy, then a theft on campus, because whenever this stuff comes up it makes doing the work of class harder. In this class, though, it was almost the other way around. Students would come in and would be like, ‘We’ve got to process this.’ It was very powerful to have the sense that such processing was sanctioned in that space, that it was our work.”

This work included President Kevin coming to class for a debriefing about the presidential election, a conversation that affected everyone deeply. It also contributed to a communique from Kevin to the college community about not tolerating xenophobia on campus.

“It was powerful for students to see the president show up to class and then immediately respond,” says Jean. “That they felt comfortable sharing honestly, despite him coming in, also speaks to the amount of work we did as a group. They understood that these conversations have to happen with everybody, not just in this classroom. This isn’t a rehearsal.”

“As we developed trust among the micro-community of the class, we began to cultivate a warm, inviting atmosphere,” says Solomon Botwick-Reis, who also acted as one of three teaching assistants. “The course was a transformative space of tenderness—tender vulnerability with each other, with issues in the Marlboro community, and with the broader realities of our nation and world.”

“As we developed trust among the micro-community of the class, we began to cultivate a warm, inviting atmosphere,” says Solomon Botwick-Reis, who also acted as one of three teaching assistants. “The course was a transformative space of tenderness—tender vulnerability with each other, with issues in the Marlboro community, and with the broader realities of our nation and world.”

Students put theory into practice in the form of community-based projects that they designed and co-created, building on the sense of reciprocity and responsibility essential to community. These projects focused on issues around classism at Marlboro, public education about smoking, and helping art students to cover materials costs.

“I began to grasp the extent to which Marlboro students can impact their campus community,” says freshman Adeel Sultan, whose group piloted a Creative Arts Co-op where students can sell their art and help other students afford art supplies. “Coming out of that experience, I feel empowered and ready to collaborate with others on future projects that benefit the community.”

“Students learned a lot about the challenges of working together, and came to a new appreciation of the difficulty of organizing and publicizing events on campus—all of that I think was a real eye-opener to them,” says Seth. “Their project equipped students with the knowledge they need, and the tools they need, to be better community members. This included an appreciation for the work of staff, and seeing that their roles are very complicated.”

“The highlight of the class for me was the intentional way we created a community in the class itself,” says Kate. “Peter Block [author of Community: The Structure of Belonging] emphasizes the idea that community is not something that exists in a pre-formed way, but is more a way of being with ourselves and each other to create change. I was profoundly moved by the work we did together in the classroom.”

Jennifer Girouard Brings It All Back to Marlboro

“My experience at Marlboro was very intense, in a good way,” says Jennifer Girouard, who graduated in 2001 with a Plan of Concentration exploring the sociology of white-collar labor. A first-generation college student, Jennifer didn’t know what to expect, so she threw herself into the Marlboro experience full steam. “I didn’t actually know what sociology was—they didn’t teach it at my high school, so I had no idea—I just got swept into it,” she says. Now, 15 years later, Jennifer is on the other side of that intense experience, as Marlboro’s new sociology professor.

“Sociology is such a broad field,” says Jennifer, reflecting on how she first gravitated toward the discipline. “It was a lens to understand the world in a new way, and to understand my own life trajectory. I think what’s always interesting for students is when they understand some of the large structural forces and start to put together pieces of ‘how did I end up here?’ Seeing that bigger picture is very useful for me. I got sucked into viewing the world through that lens, and I didn’t leave it.”

Jennifer received her doctorate in sociology from Brandeis University, but before continuing on to graduate school she spent five years working with children at a homeless shelter in Massachusetts and for Head Start in Appalachian Ohio. In the latter, she worked one-on-one with preschoolers and their families to build new skills, broaden early development experiences, and monitor their progress.

“Only when I was thinking of coming back to Marlboro did I realize that these meetings were like doing little family tutorials, sitting together and working through what was important to them,” says Jennifer. “These experiences challenged and immersed me in new social and cultural milieu, and honed my sociological lens.”

Jennifer’s doctoral dissertation, titled “When Law Comes to Town: Participation and Discourse in Fair-Share Affordable Housing Hearings,” was based on a study of four towns’ implementation of a state affordable-housing law. She was particularly interested in tracking the discourse of small-scale public hearings where everyone got together and talked—or yelled—about an issue, a forum with interesting similarities to Marlboro’s Town Meetings. Jennifer is co-editor of Varieties of Civic Innovation: Deliberative, Collaborative, Network, and Narrative Approaches.

Jennifer says that many of the things that drew her in as a Marlboro student continue to inspire her as a professor. She started teaching in the fall already aware that Marlboro’s professors are constantly being challenged and pushed to new subjects by students, to a degree rarely found at other institutions.

“When a student comes to me with an interest, I get to expand and learn alongside them. Having been a student, I understood that this was part of the job, and that’s what excited me to come back. I’m currently working with a student on immigration in Sweden. I don’t know anything about that, but now I get to learn it, and it benefits me, the student, and other students that come after.”

With a discipline as broad-ranging as sociology—essentially the study of the social world—Jennifer expects many fascinating diversions driven by student interest. She’s also eager to provide opportunities for students to participate in her ongoing research, exploring competing structures and cultural discourse through local land-use conflicts.

“I’m always interested in how we construct and contest space and land use, and I’m sure there are a lot of really interesting ways to build on that here,” Jennifer says. “I’m very interested in how we view and regulate different housing types, such as trailer parks, which here in Vermont were the hardest hit by Tropical Storm Irene.”

Jennifer recognizes that she is rejoining Marlboro at a really interesting transitional time period. There’s a lot of new energy coming in with students, and there’s a shift in faculty—with concomitant discussions of changes in the curriculum. She is excited to see what comes of these conversations, but thinks there are some core things that won’t change.

“Marlboro does so well at preparing students to think richly, deeply about the world. I was just telling Jerry [Levy, sociology professor emeritus] that when I started my doctoral program without a master’s degree, I felt completely prepared. Marlboro doesn’t prepare students for specific jobs or different career paths, but it shapes their minds in ways that are very effective, if hard to measure.”

Partner Colleges Come to Campus

In October, Marlboro College co-hosted the annual meeting for the Consortium for Innovative Environments in Learning (CIEL), a working group of 12 institutions founded on innovative and student-centered practices in higher education. A group of more than 30 colleagues from partner colleges across the country convened at Marlboro to meet with President Kevin and discuss shared governance and community engagement on campus.

“All of our CIEL partners excel in different ways to produce life-long learners and engaged citizens, but Marlboro has a unique history of leadership in the area of shared governance,” said Richard Glejzer, dean of faculty. “Together we discussed curricular initiatives and decision-making models that prepare students for a lifetime of community engagement, service, and stewardship.”

“In class, I might be Solomon’s boss, but on select board, he’s my boss,” said mathematics professor and select board member Matt Ollis, referring to head selectperson Solomon Botwick-Ries. “Except for the fact that neither is an especially boss-like relationship.” The session was followed by a reception and dinner in the campus center, where participants discussed new developments at partner institutions Green Mountain College and University of Maine at Farmington.

The CIEL meeting was cohosted by Bennington College, which offered workshops on intellectual mentorship and experiential learning. Bennington President Mariko Silver hosted a lunch discussion about equity and inclusion and the impact of recent events on aspects of civility and community on campus.

Dual Graduates Go for the Whole Marlboro

“My first residency weekend had me experiencing deja vu,” said Heidi Doyle ’94 MAT ’16 in her student address at commencement last May, referring to her experience in the graduate program. “The discussions that took place, the rigor of the work, and the self-pacing that was required seemed strangely familiar. . . I was beginning to have a sneaking suspicion that the undergraduate and the graduate campuses valued the same things.”

Heidi was the first “dual” alumnus to address the first-ever combined undergraduate-graduate commencement (Potash Hill, Fall 2016), and she gave a fitting tribute to what is a growing phenomenon. Marlboro students are finding valuable continuities and rewarding careers by following their undergraduate degree with one of the college’s graduate programs.

“Nearly 30 students, with several more on the way, have completed both their bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Marlboro, bringing theory into practice through a graduate program in teaching or management,” says Kate Jellema, associate dean for graduate and professional studies. “We have much to learn from these ‘bi-lumni,’ and their positive stories are even more poignant as we move the graduate program to Potash Hill this year."

“The two programs have so much in common: extraordinary faculty, small classes, emphasis on community, and the opportunity for each student to study and pursue what he or she is most passionate about,” says Sarah Swift ’04, who completed her Capstone for an MS in Management in December. Sarah’s Plan in sociology and photography focused on the social and psychological aspects of dying and grieving, including making photographic quilts with people facing end-of-life issues. For her Capstone she established a nonprofit called Sewing Our Stories.

“I felt drawn to figuring out how to develop a nonprofit that could use traditional crafts, such as the photographic quilting I’d done for my Plan, with people at the end of life as a way to honor and affirm their lives,” says Sarah, who works at a hospice council in Augusta, Maine. “In a way, my graduate Capstone felt like an extension of my Plan— with the support of my coursework and faculty adviser, I was able to develop and launch this nonprofit project.”

“I felt drawn to figuring out how to develop a nonprofit that could use traditional crafts, such as the photographic quilting I’d done for my Plan, with people at the end of life as a way to honor and affirm their lives,” says Sarah, who works at a hospice council in Augusta, Maine. “In a way, my graduate Capstone felt like an extension of my Plan— with the support of my coursework and faculty adviser, I was able to develop and launch this nonprofit project.”

Adam Katrick ’07 did his Plan in biology and writing, specifically wolf biology, and last fall completed his MS in Management with a concentration in nonprofit management. In the process he has started his own nonprofit to teach people in the region about wolves, called Wolfgard Northeast, and is embarking on a campaign to build a wolf center in Southern Vermont.

“We’ve got a really dynamic, energized board of directors, a number of dedicated supporters, and have run programs from New York City to Burlington and many places in between,” says Adam, who lives in Marlboro. “Every week I get the opportunity to teach people about wolves. I’m more immersed in my relationship with the wilderness and wolves than ever before. It’s such a joy to see people’s faces when I tell them we’re building a wolf center—there’s so much excitement there.”

“I found that having gone through the Plan process made the Capstone project at the end of my graduate program far less intimidating,” says Francisco Mugnani ’10 MAT ’14. Francisco’s Plan in film/video studies focused on examining patterns in the narrative structure of hero myths, and his Capstone involved creating an online course to learn video production. “In both projects I worked one-on-one with a professor, set goals, and worked toward a project that exhibited my learning. The Capstone was different, however, in that the focus was more on applying my learning to help another person or organization.”

Francisco has gone on to work as a media producer and teacher, giving film instruction and helping out with several independent video projects, most often in schools. He is currently working at the Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro. “I delight in helping kids find their books and in witnessing firsthand how the library is working to evolve with emerging technologies and new ideas about how people learn,” he says.

Francisco has gone on to work as a media producer and teacher, giving film instruction and helping out with several independent video projects, most often in schools. He is currently working at the Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro. “I delight in helping kids find their books and in witnessing firsthand how the library is working to evolve with emerging technologies and new ideas about how people learn,” he says.

Geordie Morse ’13 MATESOL ’16 did his Plan on Asian studies and education, specifically on issues concerning the contemporary Japanese education system, such as how history textbooks influenced, and were influenced by, modern politics and culture. After graduating from Marlboro he spent a year gaining valuable firsthand experience as an English teacher in Japan, then returned to get his MA in TESOL.

“I wanted to continue my studies in an institution that shared Marlboro’s ideals and ethics of education,” says Geordie. “I was looking for small class sizes and a program that made my contributions feel worthwhile. What stands out to me about the graduate program is how dedicated and passionate the professors are about the mission of their programs, and how much care and attention they are willing to give their students to help them succeed.”

“My favorite thing about the graduate program was the conversations during the face-to-face weekends,” says Heidi Doyle, who is now a library media and technology integration specialist at Sunapee Central Elementary School in New Hampshire. “Because all of my classmates came from such diverse backgrounds, they brought a unique perspective to the conversation. We were all trying to accomplish the same goals, but our purpose and intent for those goals were vastly different.”

Like many “bi-lumni,” Heidi found similarities between her undergraduate and graduate experiences, including the rigor of work, the quality of discussion, and a certain “quirkiness.” “Small class sizes and intimate relationships with classmates and professors is prevalent in both programs. Those relationships enrich both your professional and personal life and provide a safe environment for taking risks.”

Or in Francisco’s apt words, “If you think of Marlboro undergrad as a movie, the Marlboro graduate program is like a great sequel. It preserves many of the core elements that made the original successful, but expands it in a bold new direction.”

Although not technically a dual alumnus, Ahmed Salama drives home the idea that there is something synergistic in Marlboro’s undergraduate and graduate programs. A native of Egypt, Ahmed taught Arabic to undergraduate students as Marlboro’s Fulbright Fellow for Arabic Language in the 2008–2009 academic year. After working for several years as head of the foreign languages department at Learning Services and Solutions Center in El Mahalla El Kubra, Egypt, Ahmed was back at Marlboro last summer, participating in the MA in TESOL program.

Storied Faculty Members Move On

Three of Marlboro’s most senior faculty will be retiring this academic year, after a combined 134 years of dedicated service to the college and mentorship to countless adoring students. The college made the decision to remove a retirement benefit introduced in 2007, for budgetary reasons, and T. Wilson (literature and writing), Geraldine Pitmann de Batlle (literature), and Stan Charkey (music) elected to take the benefit before it disappeared.

“How does one describe the singular, formative love between teacher and student?” asks Amanda DeBisschop ’10, who was one of T.’s Plan students and is now a teacher herself at Leland & Gray High School in Townshend, Vermont. We’re not sure we have the answer, but we figure that former students of these formidable faculty members will be in the best position to take a stab at it.

“How does one describe the singular, formative love between teacher and student?” asks Amanda DeBisschop ’10, who was one of T.’s Plan students and is now a teacher herself at Leland & Gray High School in Townshend, Vermont. We’re not sure we have the answer, but we figure that former students of these formidable faculty members will be in the best position to take a stab at it.

Amanda continues, “From the first, I knew that I wanted to know T. Hunter Wilson. I felt soon after seeing him on campus, at Town Meeting, that there was something I had to learn from him. And what I learned was the incredible feeling of someone taking my writing seriously. In my entire life, there had been no one to assess my work on an academic level. He helped me to feel credible. He treated my work as though it were a contribution to the larger world of poetry. He also taught me the value of accountability in a partnership, both as a student and doubly as a teacher, now, of my own students.”

T. first taught writing and literature at Marlboro in 1968, after receiving his MFA from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and in addition to teaching he has done stints as dean of faculty and, twice, as director of the World Studies Program. Always engaged in the campus community, he has served as Town Meeting moderator, Community Court justice, and member of countless committees.

“I still, 40-plus years later, vividly remember the eagerness with which I looked forward to our meetings,” says Kathryn Kramer ’75, now a published author and professor of literature at Middlebury College. “I could have listened from dawn till dusk to T. talking about my manuscript. This kind of attention, this kind of uninflected reading, is an enormous gift to a young writer, and I have remembered that experience over the years as I’ve gone on to teach writing myself.”

“I still, 40-plus years later, vividly remember the eagerness with which I looked forward to our meetings,” says Kathryn Kramer ’75, now a published author and professor of literature at Middlebury College. “I could have listened from dawn till dusk to T. talking about my manuscript. This kind of attention, this kind of uninflected reading, is an enormous gift to a young writer, and I have remembered that experience over the years as I’ve gone on to teach writing myself.”

“I think the best thing about working with T. was that he really did let you come to conclusions on your own,” says Cate Marvin ’93, now a published poet and professor of creative writing and literature at Colby College. “In this respect, he was very patient. He also acknowledged the hard work of writing. One week I turned in 11 poems, but they were all bad. And T. told me that the fact I’d written that many poems and didn’t give up was a better sign than if the poems had been good. So he taught me the notion of perseverance.”

“T. is a brilliant teacher and editor, and he made me feel brilliant, too,” said Molly Booth ’14, whose Plan project was the young adult novel Saving Hamlet, published by Disney Hyperion last November. “I left his office charged with energy, and annoyed with the 20 steps it took to get to the library, where I could sit down and write. With T., I learned how to write and edit, how to develop characters, how to listen to my creative gut . . . everything we did together applies to what I do now. When I feel uncertain in my writing, I return my mind to Marlboro, and think what discussion T. and I would be having about this word, or that character.”

Nearly as senior as T. is Geraldine Pittman de Batlle, who joined Marlboro in 1969 after advanced graduate study at Southern Illinois University and Columbia University. Known for her passion for literature ranging from English Romantic poetry to modern fiction, Geri won the adoration of students who enjoyed working closely with her on projects of mutual interest.

Nearly as senior as T. is Geraldine Pittman de Batlle, who joined Marlboro in 1969 after advanced graduate study at Southern Illinois University and Columbia University. Known for her passion for literature ranging from English Romantic poetry to modern fiction, Geri won the adoration of students who enjoyed working closely with her on projects of mutual interest.

“Geri conveyed a love of literature that was infectious,” says Chris Davey ’93, a freelance editor who says he daily applies the skills she taught. “Her request that students show attentiveness to and respect for words struck me as profoundly ethical, as a call to bear witness to the power of words and the effects of that power, to recognize the ways great literature enacts empathy, and then to go beyond, to seek to hear for oneself ‘the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat,’ to brave ‘the roar which lies on the other side of silence.’”

“The amount of writing I had to do for Geri was intense,” says Ron Mwangaguhunga ’94, now a working writer and editor in New York City with a novel on the way. “Good or bad thoughts, Geri wanted me to get them on paper just to get in the practice of regular writing. Her patience, compassion, and, above all, demand for excellence—and always, always, more writing— helped me massively with the work I do today.”

“I was always happy working with Geri,” says Sue Crimmins ’89, now a landscape designer. “I saw her every day, and we made each other smile. Even on those days that I had not finished even a paragraph of my Plan, she held me as closely as any member of her family. We would sit right down next to each other and plow through all the words and all the sentences and all the paragraphs, clarifying every idea. She was my teacher, but also a good friend, and my strictest tutor. I am still sorting my ideas, and words, and reaching for clarity in everything I do.”

“I was always happy working with Geri,” says Sue Crimmins ’89, now a landscape designer. “I saw her every day, and we made each other smile. Even on those days that I had not finished even a paragraph of my Plan, she held me as closely as any member of her family. We would sit right down next to each other and plow through all the words and all the sentences and all the paragraphs, clarifying every idea. She was my teacher, but also a good friend, and my strictest tutor. I am still sorting my ideas, and words, and reaching for clarity in everything I do.”

“Geri has tremendous respect and patience for literature,” says Ryan Stratton ’11, who works as an admissions counselor at Marlboro. “I think that one of the best lessons I learned from Geri was reverence—in a contemporary world where irony is used as social and intellectual capital, I think it was a humbling experience to really sit down and listen to what Dante was trying to say about self-growth and love for others. Geri had a reputation for being a tough teacher—I would say that she has only the highest expectations for her students, because she knows them and has faith in them, and wants them to reach their fullest potential.”

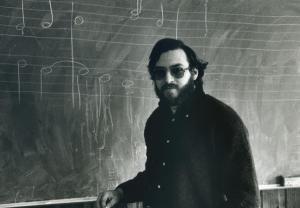

Music professor Stan Charkey, the Luis C. Batlle Chair in Music, has taught music at Marlboro since 1977, when he received his Master of Music degree from the University of Massachusetts. A composer and performer of note, Stan had premieres of new works performed in Paris, Los Angeles, Washington, and of course Marlboro.

“I appreciated that Stan held his students to high standards, but always allowed us the space to pursue our interests independently,” says Allen Magana ’13, a graduate student in Latin American and Iberian studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “He respected us as scholars and never expected anything less from our work. Stan offered me the opportunity to prove to myself that I have the ability to complete top-level scholarship. This experience gave me the confidence to continue to pursue academic research, and I hope someday to foster this same love of scholarship in my own students.”

“I appreciated that Stan held his students to high standards, but always allowed us the space to pursue our interests independently,” says Allen Magana ’13, a graduate student in Latin American and Iberian studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “He respected us as scholars and never expected anything less from our work. Stan offered me the opportunity to prove to myself that I have the ability to complete top-level scholarship. This experience gave me the confidence to continue to pursue academic research, and I hope someday to foster this same love of scholarship in my own students.”

“My favorite part about working with Stan is that he was extremely open-minded to my ideas as a composer,” says Felix Jarrar ’16, already an accomplished composer and pianist in the New York area. “During my lessons with him, he would always give me constructive feedback on how my musical gestures would or wouldn’t work toward my larger musical goals. He had a lot of really great suggestions for pieces to listen to if I found myself ‘stuck.’ My work with Stan has helped me immensely since leaving Marlboro. When I write music, I use all of the contrapuntal and compositional skills he taught me.”

“Stan’s regard for a student was, for me, ideal,” says Peter Blanchette ’92, a musician, composer, and founder of the Happy Valley Guitar Orchestra. “He neither pampered you through the maddeningly tricky counterpoint exercises, nor disrespected your earnest effort. On the other hand, he would expose the weaknesses in your results with firmness, followed by excellent suggestions of how to improve. He taught me more about what makes great music tick than anyone else in my life, and every single day that I work, I apply musical understanding that he brought into my life.”

“Stan’s regard for a student was, for me, ideal,” says Peter Blanchette ’92, a musician, composer, and founder of the Happy Valley Guitar Orchestra. “He neither pampered you through the maddeningly tricky counterpoint exercises, nor disrespected your earnest effort. On the other hand, he would expose the weaknesses in your results with firmness, followed by excellent suggestions of how to improve. He taught me more about what makes great music tick than anyone else in my life, and every single day that I work, I apply musical understanding that he brought into my life.”

“He was always ready to put some beautifully intricate piece in front of us and have at it,” says Mike Harrist ’10, a professional musician and music teacher in Boston. “His joy in reading and playing is deep and infectious. Looking back, I’ve learned many lessons just from this one aspect of our time together. Joy in making music and a realistic perspective on one’s ability are not antithetical. Holding both together fuels improvement and leads to a grounded musicality. Stan’s teaching and high standards continue to inspire me to be a better musician and more rigorous thinker.”

One of Amanda DeBisschop’s fondest memories is when she joined T. Wilson to hear poet Gary Snyder, one of his mentors, and they approached Gary after the reading. When Gary said to T., “Shouldn’t you be close to retiring now?” Amanda piped in, “He can’t retire. I wouldn’t know what to do.”

All in the college community share Amanda’s sentiments about T., and feel just the same about Geri and Stan, but acknowledge that this is a shortsighted response. Amanda concurs: “I simply want every other Marlboro student to have access to the person who taught me the most valuable things that I know: to be a conscious part of a community, to write as though my life depends on it (and it does), and to do good work.”

Also of Note

Woodrow Wilson Fellow Marcia Grant (pictured right) was on campus for a week in October to engage in all things Marlboro, from attending Town Meeting to visiting classes both on Potash Hill and at the graduate campus. Marcia is currently provost of the American University in Paris, and has a distinguished career in global higher education, including serving in institutions in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. While at Marlboro she made presentations to the campus community on international careers, favorite books, and the global impact of liberal arts education.

In November, MA in Teaching with Technology student Jasmin Bey Cowin was elected president of the Rotary Club of New York #6, where she has been active for 10 years. Guided by her passion for “education as the tool for transformative empowerment and a pathway to a fulfilling life,” Jasmin will coordinate the club’s community, city, and international service projects. An accomplished educator herself, she holds both a master’s and doctorate in education from Teachers College at Columbia University.

In October, Stephanie Sopka joined the campus as technical services librarian. “I like getting to see all of the books that come in,” says Stephanie. She came to Marlboro from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she completed her MS in library and information science and worked in the university law library. “I have spent a lot of time studying feminist theory and queer theory, so I’m excited to expand our collection in these areas, and to support students and faculty in their work.”

“There are those who have access to technology, but they don’t have the knowledge and skills to use this technology to support learning in school,” said Emmanual Ajanma (pictured right) during his Capstone presentation about bringing Google Apps to a school in Nigeria. Emmanual was one of 10 students in the MAT, MSM, and MBA programs who presented their Capstones in November. Other presenters included Dhruv Jagasia on developing a socially-conscious eyewear brand and Missy Munoz on promoting sustainable building standards for low-income housing. See an excerpt.

“There are those who have access to technology, but they don’t have the knowledge and skills to use this technology to support learning in school,” said Emmanual Ajanma (pictured right) during his Capstone presentation about bringing Google Apps to a school in Nigeria. Emmanual was one of 10 students in the MAT, MSM, and MBA programs who presented their Capstones in November. Other presenters included Dhruv Jagasia on developing a socially-conscious eyewear brand and Missy Munoz on promoting sustainable building standards for low-income housing. See an excerpt.

Marlboro College made the short list for “10 colleges where joining student clubs is easy” released in February by U.S. News and World Report. Drawn from U.S. News’ survey of more than 1,800 colleges and universities nationally, Marlboro is the only New England college in the top 10 and tied second with Hamilton College in New York State. Marlboro was rated as having 6.1 students per club, nine times the average among the 1,195 ranked schools that reported these data in an annual survey.

Sophomore Spencer Knickerbocker, student trails steward, was instrumental to the success of Trails Day 2016 in October, which drew 20 volunteers despite the cold, rainy weather. “I was pleasantly surprised by the great enthusiasm of volunteers and their willingness to work,” says Spencer, who spent four years training as a nordic skier and is delighted to discover Marlboro’s trails. “I have traveled around the world to the hotbeds of nordic sport, yet I never found a place with so many trail options as Marlboro.”

New graduate faculty member Kevin McQueen (pictured right) brings extensive experience in corporate finance, with a deep commitment to facilitating social change through mission-driven organizations. Marlboro College Graduate and Professional Studies was pleased to welcome Kevin and four other new faculty members recently, part of the ongoing development and enrichment of the management program. Kevin, Beth Tener, and Melinda Weekes-Laidlow joined Marlboro in the fall, each of them bringing new skills and expertise in corporate finance, collaborative leadership, and organizational development. This winter, Jude Smith Rachelle and Carol Stimmel joined the management faculty to co-teach an MBA seminar in Performance Measurement and Analytics. You can learn more about these new faculty members and their impressive backgrounds on the college website.

New graduate faculty member Kevin McQueen (pictured right) brings extensive experience in corporate finance, with a deep commitment to facilitating social change through mission-driven organizations. Marlboro College Graduate and Professional Studies was pleased to welcome Kevin and four other new faculty members recently, part of the ongoing development and enrichment of the management program. Kevin, Beth Tener, and Melinda Weekes-Laidlow joined Marlboro in the fall, each of them bringing new skills and expertise in corporate finance, collaborative leadership, and organizational development. This winter, Jude Smith Rachelle and Carol Stimmel joined the management faculty to co-teach an MBA seminar in Performance Measurement and Analytics. You can learn more about these new faculty members and their impressive backgrounds on the college website.

Last fall a team of undergraduate and graduate faculty, staff, and students made several visits to Ashoka Changemaker Campuses, including College of the Atlantic, College of Social Innovation, and Brown University. Along with a discussion at Town Meeting in September, these visits were important steps toward Marlboro College being recognized as a Changemaker Campus by Ashoka, a global organization that promotes positive change by supporting social innovation. “The team has been working hard over the last few months, and we’re eager to share our progress with you,” says Kelsa Summer ’13, a student in the MS in Management program. Learn more.

Community Spirit  Freshman Cyane Thomas joined 14 other students, staff, and faculty in a United Way Day of Caring project, giving a fresh coat of paint to the local little league field, in September.

Freshman Cyane Thomas joined 14 other students, staff, and faculty in a United Way Day of Caring project, giving a fresh coat of paint to the local little league field, in September.

Most Important Meal Junior Emily Motter and chemistry professor Todd Smith help serve up breakfast at the Marlboro Community Town Fair in September, raising money for the college farm.

Junior Emily Motter and chemistry professor Todd Smith help serve up breakfast at the Marlboro Community Town Fair in September, raising money for the college farm.

Getting Green In October, members of the Environmental Studies Colloquium participated in a clean-up on the Connecticut River, finding many articles too gross to mention.

In October, members of the Environmental Studies Colloquium participated in a clean-up on the Connecticut River, finding many articles too gross to mention.

Learning to Spell Senior Crystal Graybeal, junior Kristen Thompson, and sophomore Dan Medeiros strike a magical pose at the Hogwarts Dinner in October, which welcomed local families.

Senior Crystal Graybeal, junior Kristen Thompson, and sophomore Dan Medeiros strike a magical pose at the Hogwarts Dinner in October, which welcomed local families.

Events

1 Acclaimed pianist Jonathan Biss played a program of Beethoven, part of a series of concerts to honor the memory of beloved music professor Luis Batlle. 2 In October, Yawanawá tribe members from the remote Amazon forest sang ancestral songs and shared their rich culture in a presentation called “Journey to Mutum.” 3 In September, world-renowned eco-philosopher Joanna Macy gave a talk titled “Teaching at the Edge of Time” at Brattleboro’s Congregational Church. Photo by Joan Beard 4 Students, faculty, and staff all participated in “Dances in the Rough,” the annual fall concert of student choreography and dance performance, in Serkin Dance Studio. 5 In September, visiting choreographer Joshua Monten presented Kill Your Darlings, exploring body percussion, partnering, and making a big mess, outside the dining hall. 6 Two independent filmmakers from Ecuador screened Encounters with Cinema, a work about their intensive program for youth to learn both film production and local oral tradition. 7 In November, theater professor Jean O’Hara and a merry band of students presented Marlboro College and the Holy Grail, a timeless adaptation of the Monty Python film.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

Junior Hannah Noblewolf sat down with religion professor Amer Latif in November to talk about ritual, diversity of opinion, and manifesting peace through waving. You can read the whole interview.

Hannah: What about Marlboro made you want to teach here?