On and Off the Hill

All the news that fits, including the Embodied Learning Symposium, Movies from Marlboro, a class trip to the baths of Caracalla and a meeting called SymBiotic Art and Science. Plus commencement, of course, and faculty, students and staff worthy of note.

All the news that fits, including the Embodied Learning Symposium, Movies from Marlboro, a class trip to the baths of Caracalla and a meeting called SymBiotic Art and Science. Plus commencement, of course, and faculty, students and staff worthy of note.

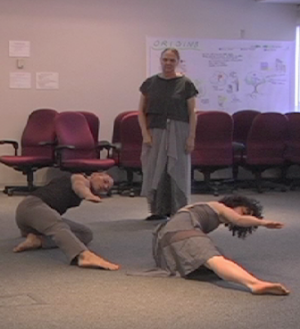

Symposium transcends mind-body dualism

In April, Marlboro students, faculty and staff joined with invited guests to explore concepts of embodied learning, drawing from both Eastern and Western traditions that embrace physicality, perception and context. The Embodied Learning Symposium consisted of four action-packed days of open classes, presentations and workshops on breaking down the Cartesian mind-body dualism often found in the classroom and studio.

“Embodied learning seems like something that ought to be intuitive,” said Asian studies professor Seth Harter, who organized the symposium in collaboration with the Vermont Performance Lab and with support from the Freeman Foundation for Undergraduate Asian Studies Initiative II. “Heads and bodies—when you see them apart it’s already too late. We all have bodies—we can’t think without them—and yet that fact often goes unrecognized, if not actively dismissed, in our liberal arts teaching work.”

Participants heard from leading scholars and practitioners of embodied learning such as acclaimed playwright and director Ain Gordon, who combines theater and performance art to bring forgotten histories to life. Livia Kohn, Daoist scholar and Boston University professor emerita, led participants through an embodied sense of Chinese cosmology, and University of Toronto professor Roxana Ng discussed “decolonized” learning. Participants had opportunities to experience T’aichi Ch’uan, West African dance, yoga, energy dance and Japanese movement traditions firsthand. But perhaps the most rewarding presentations were by Marlboro faculty who have embraced the concept of embodied learning in their own classes.

“In reading poems, we’re thinking about what it is we need to know about the poems, how we need to think about the range of emotions, changes in tone, the dynamics of the poem, in order to read it well,” said literature professor T. Wilson. Students from his Embodied Poetry class recited poems, with feeling, ranging from Robert Frost’s “Birches” to Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody blew up America.”

“In reading poems, we’re thinking about what it is we need to know about the poems, how we need to think about the range of emotions, changes in tone, the dynamics of the poem, in order to read it well,” said literature professor T. Wilson. Students from his Embodied Poetry class recited poems, with feeling, ranging from Robert Frost’s “Birches” to Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody blew up America.”

“I think there’s a kind of internalization that happens when you have to repeat a poem on demand,” said Ellie Roark ’12. “We embodied the mindset of the speaker.”

Students in Tim Segar’s class, The Body, shared some of their novel approaches to the age-old subject of the human form, from Shea Witzenberger’s ’12 bulbously corporeal soft sculptures to Aaron Evan-Browning’s ’12 electronic headband that translates facial expressions to sounds. Members of Cathy Osman’s class, Two Arms, Two Legs and a Head, shared the results of experimentally restraining their painting stroke to remind themselves of the physicality of painting. Students reported that they found the experiment freeing, even comforting, and the resulting figure paintings felt less contrived.

“‘I think therefore I am’ no longer sufficiently explains a lot of things that are going on in terms of social movements inspired by desires,” said politics professor Meg Mott in a presentation from her class, Spinoza & Freedom. She described going beyond students’ thoughts to make their emotional reactions to subjects part of the class discussion. “Maybe Spinoza’s tagline would be ‘I think I am affected, therefore I am empowered.”

Visiting language professor Michael Huffmaster discussed the bodily basis of semantics and thought, and ceramics professor Martina Lantin and visiting photography professor Lakshmi Luthra ’05 discussed art theory and practice. Anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson and Sari Brown ’11 talked about their recent visit to Bolivia, inspired by Sari’s field research there and by a course taught last fall by Carol and religion professor Amer Latif called Thinking Through the Body.

“Starting a few years ago, in the course of conversations with students and colleagues, I started to see a strange phenomenon—people started to talk about these ideas of embodiment,” said Seth, who led a discussion based on his class, Making Way: Daoist Ritual and Practice. “People started to question the epistemological significance of the connections between the mind and the body and the cost of ignoring those connections. They questioned bracketing out feelings or emotions or sensory input or physical limitation from the kind of work we were doing, even in history class or philosophy class. I saw the Embodied Learning Symposium as an opportunity for those conversations to come together.”

College launches film intensive

Film studies students have found significant opportunities to work with professor Jay Craven, from assisting on the set of his 2007 feature film, Disappearances, to collaborating on Marble Hill, a television sitcom based on a small, liberal arts college in Vermont. Next spring the college will take film studies to a new level, through an intensive program that partners college students with seasoned filmmakers for the production of a dramatic feature film starring professional actors and aimed for national release.

Film studies students have found significant opportunities to work with professor Jay Craven, from assisting on the set of his 2007 feature film, Disappearances, to collaborating on Marble Hill, a television sitcom based on a small, liberal arts college in Vermont. Next spring the college will take film studies to a new level, through an intensive program that partners college students with seasoned filmmakers for the production of a dramatic feature film starring professional actors and aimed for national release.

Movies from Marlboro, a semester-long film intensive, starts in January 2012 with a week at the Sundance Film Festival. This will be followed by “north country” literature and cinema study as well as hands-on preparation and production of a film based on Howard Frank Mosher’s award-winning novel Northern Borders.

“This new film intensive program grows out of my long experience working with young filmmakers and my years of producing and releasing north country films produced on significantly larger budgets,” said Jay. “Based on these experiences and new developments in independent film production and distribution, I believe that this Marlboro College film intensive will provide a rich learning opportunity and help chart a new course for how independent films get made and distributed.”

Eight film professionals will mentor up to 20 college students and play leading roles as department heads for the film. Independent filmmaker Chip Hourihan, who produced the Academy Award–nominated Frozen River, will partner with Jay to produce the film on a contract with the Screen Actors Guild. Based on their interest and experience, students will earn both college credit and professional film credit as they study, train and practice in every corner of production—as actors, camera operators, unit directors, producers, set designers, costume designers, production assistants and more.

“Marlboro College has, since its founding, believed in students’ potential to take on substantial leadership and responsibility and to challenge themselves on ambitious and potentially transformative Projects,” said Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president. “This Project is a perfect fit for us, and I’m especially pleased that we’ll launch it using the work of one of Vermont’s most talented writers, Howard Frank Mosher, who has done so much to enlarge our imagination of our region.”

“Marlboro College has, since its founding, believed in students’ potential to take on substantial leadership and responsibility and to challenge themselves on ambitious and potentially transformative Projects,” said Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president. “This Project is a perfect fit for us, and I’m especially pleased that we’ll launch it using the work of one of Vermont’s most talented writers, Howard Frank Mosher, who has done so much to enlarge our imagination of our region.”

Jay envisions participation that will include undergraduate and graduate students in not only film but also theater, visual arts and photography. Students from other U.S. colleges are eligible to apply for the program, joining with Marlboro students on the Project.

“Motivated college students possess keen intelligence, formidable skills and a strong desire to work on Projects that engage them,” Jay said. “They can do the work required to make a first-class film, serving in leadership roles and guided by professionals. My own experience shows me that nothing helps to accelerate an emerging filmmaker’s path more quickly than this kind of intensive exposure, which can otherwise take years to achieve. We’re working to give students a chance—sooner than they might otherwise have—to intensify their practice and earn a substantial film credit to help launch their careers.”

For more information, go to movies.marlboro.edu or contact Jay Craven.

Students lay siege to Rome

“The ruins of Rome can be hard to comprehend secondhand,” said classics fellow William Guast, who taught a class this spring semester called Rethinking Rome: Power, Society and Faith in the Roman Empire. “Many sites are too large or too complex for their layout, function or impact to be fully comprehended in printed form.” In March, William’s class had a chance to experience Roman history firsthand, through the art, architecture and archaeology of the city of Rome itself and other sites nearby.

“The ruins of Rome can be hard to comprehend secondhand,” said classics fellow William Guast, who taught a class this spring semester called Rethinking Rome: Power, Society and Faith in the Roman Empire. “Many sites are too large or too complex for their layout, function or impact to be fully comprehended in printed form.” In March, William’s class had a chance to experience Roman history firsthand, through the art, architecture and archaeology of the city of Rome itself and other sites nearby.

“I experienced the actual scope of history,” said Sam King ’12, one of the nine students who participated and who is designing a Plan of Concentration on utopias. “Reading about Trajan’s Column, you don’t realize how big it is. That’s big in a symbolic sense, ancient and powerful and so on, but also very, very tall and hard to read. I was constantly in awe.”

William’s class considered how the Roman emperors tried to control their image through art and architecture, from the palaces they had built for themselves to the baths and amphitheaters with which they hoped to entertain the masses. Some of the highlights of their trip included the Colosseum (of course), the huge baths of Caracalla and a day trip to the Roman port town of Ostia to learn about the lives of the urban poor.

“A particular and unexpected highlight was the church of San Clemente, built on top of an early Christian basilica, which was itself built on top of a first-century temple to the god Mithras and an apartment block,” said William. The students were intrigued by the radically unfamiliar Roman religious system, visiting the great pagan temples such as the Pantheon, the dark catacombs where Christians and Jews were laid to rest and the monumental churches that heralded the final triumph of Christianity. “Another favorite was Rome’s cat sanctuary, situated in the ruins of four Roman temples.”

“All the different landmarks that we read about in our Roman history readings were now tangible and accessible,” said Paul Lee ’14, who is interested in history and, now, learning Italian. “We got to visit so many historic sites that came alive in a way they couldn’t by simply looking at pictures or reading about them.”

“All the different landmarks that we read about in our Roman history readings were now tangible and accessible,” said Paul Lee ’14, who is interested in history and, now, learning Italian. “We got to visit so many historic sites that came alive in a way they couldn’t by simply looking at pictures or reading about them.”

Students were asked to analyze these monuments and sites in person, as ancient Romans would have experienced them. As they moved about the city, they explored the relationship of one monument to another, such as Trajan’s “triad” of interrelated monuments—his forum, his column and his markets—or the emperors’ successive attempts to outdo one another in monuments on the Campus Martius.

“We’ve been discussing Roman town planning in class, and it was great to be able to say ‘in towns like Ostia, or Pompeii’ and know that the students had firsthand experience of what we were talking about,” said William. “When we came to Roman religion, it was great to be able to refer to ‘early Christian art’ and know that the students had seen countless examples in Rome’s museums.”

Meanwhile, during one of the longest winters in recent memory, a different group of Marlboro students visited springtime during Spring Break, traveling to South Carolina to do community service work with Habitat for Humanity. Pictured left to right are (top row) Hannah Ruth Brothers ’13, Casey Friedman ’12, Jonathan Wood ’12, counseling intern Allison Fisette, Emily Field ’11, (middle row) Randy Morantes ’14, Shyloh Favreau ’13, David Amato ’13, (front row) Nick Rouke ’12 and Clare Hipschman, student life coordinator.

Meanwhile, during one of the longest winters in recent memory, a different group of Marlboro students visited springtime during Spring Break, traveling to South Carolina to do community service work with Habitat for Humanity. Pictured left to right are (top row) Hannah Ruth Brothers ’13, Casey Friedman ’12, Jonathan Wood ’12, counseling intern Allison Fisette, Emily Field ’11, (middle row) Randy Morantes ’14, Shyloh Favreau ’13, David Amato ’13, (front row) Nick Rouke ’12 and Clare Hipschman, student life coordinator.Meeting explores symbiosis of art and science

In March, a group of leading scholars in the life sciences, literature, visual arts and dance gathered at the National Science Foundation (NSF) in Arlington, Virginia, to explore what happens when artists and scientists work together. The conference, called “SymBiotic Art and Science,” was conceived by Marlboro President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell and colleague Dr. Christopher Comer, a neuroscientist and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Montana.

In March, a group of leading scholars in the life sciences, literature, visual arts and dance gathered at the National Science Foundation (NSF) in Arlington, Virginia, to explore what happens when artists and scientists work together. The conference, called “SymBiotic Art and Science,” was conceived by Marlboro President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell and colleague Dr. Christopher Comer, a neuroscientist and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Montana.

“Where the arts and sciences come together they are creating a new synthesis, new ways of knowing,” said Ellen. “The scientists call on the artists to ‘re-enchant the world,’ and the artists need the scientists to observe and understand the world. The artists talked about their experiments, and the scientists their intuitive leaps. They found that not only do artists and scientists inform each other’s work, they can also cooperate to generate new creativity. However, this kind of collaboration is not often recognized within academic arenas or by funding agencies.”

Co-sponsored by the NSF and the National Endowment for the Arts, the meeting involved 24 participants ranging from Liz Lerman, founding artistic director of the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, to University of Vermont theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman. Included were an art photographer who specialized in images of scientific experiments, a psychologist who analyzed literary characters and a rainforest ecologist who invited a Detroit rap artist into the forest canopy to communicate with urban youth about forest preservation. Participants from biology, astronomy, performance art, biomimicry, dance, painting, art conservation, bio-art, ecology and geology enriched the agenda as they mapped the range of possibilities.

“I have never considered my engagement in science as distinct from my activity as an artist,” said Bevil Conway, who teaches neuroscience at Wellesley College, with a focus on visual perception. “Although art and science differ in their modes of production, their expert communities and often their quantifiable utility, both avenues of investigation have provided me with a mechanism to appreciate, and hopefully uncover, the mysteries of perception. Both are fun.”

“The whole symposium was incredibly relevant to what we do here at Marlboro,” said dance professor Kristin Horrigan, who co-taught an Anatomy of Movement class with biology professor Jaime Tanner last fall. “I think that the big message I took home was that we could do a lot more of this, and it would be really healthy for our campus if we made a deliberate effort to create

“The whole symposium was incredibly relevant to what we do here at Marlboro,” said dance professor Kristin Horrigan, who co-taught an Anatomy of Movement class with biology professor Jaime Tanner last fall. “I think that the big message I took home was that we could do a lot more of this, and it would be really healthy for our campus if we made a deliberate effort to create

more art-science connections.” Rounding out the Marlboro contingent were alumna Melanie Gifford ’73, who works at the National Gallery as a conservator of 16th- and 17th-century paintings, and film student Jesse Nesser ’13, who documented the meeting.

“There was a spontaneous and very poignant discussion about the conditions under which this work happens and flourishes, about generative environments,” said Ellen. The majority of participants who had academic affiliations were from small liberal arts colleges, and two from big universities admitted that they collaborated across disciplines in spite of their institutions. When participants from Europe pointed out that European colleges offer combination art-science degrees, it didn’t escape Ellen and Kristin and Melanie and Jesse that this is also possible at Marlboro. “When you think about generative environments, it is incredibly reinforcing of our Marlboro model,” said Ellen.

Black History Month events accentuate the positive

If you had an interest in pop music during the 1960s civil rights movement, the Harlem Renaissance or 19th-century African-American farmers in Vermont, Marlboro was the place to be in February. For Black History Month, the college had a wide array of events celebrating the contributions of African-Americans to American culture and society.

If you had an interest in pop music during the 1960s civil rights movement, the Harlem Renaissance or 19th-century African-American farmers in Vermont, Marlboro was the place to be in February. For Black History Month, the college had a wide array of events celebrating the contributions of African-Americans to American culture and society.

Vermont historian Elise Guyette kicked off the program with a discussion of her book Discovering Black Vermont: African-American Farmers in Hinesburgh, Vermont, 1790–1890. The book, which won the 2010 Award of Excellence from the Vermont Historical Society, tells the story of a small black community in northern Vermont that was apparently accorded fair treatment and respect from its white neighbors during a period of U.S. history that spans legalized slavery and Jim Crow laws. Guyette’s lecture took the audience through her process of discovering court documents, town records, newspaper articles and other primary sources to construct what the Valley News calls “a quintessential Vermont pioneering story.”

Later in the month, legendary jazz bassist William Parker brought an octet to the Whittemore Theater to perform music from his 2010 release, I Plan to Stay a Believer: The Inside Songs of Curtis Mayfield. Parker’s group included poet, playwright and activist Amiri Baraka, who founded the Black Arts Movement in Harlem during the 1960s and authored the Obie-winning play Dutchman. Parker and other band members also met with students and faculty to discuss the intersection between art and social consciousness during that era among African-Americans in general, and Curtis Mayfield in particular.

“If you had ears to hear, you knew that Curtis was a man with a positive message—a message that was going to help you to survive,” Parker said. His band performed jazz renditions of Mayfield’s songs, such as “People Get Ready,” “Move on Up” and “Keep on Pushing,” which became anthems of black power and black pride in the 1960s and ’70s.

The final event was a lecture and reading by author and University of Vermont Professor Emily Bernard, entitled “Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance.” Bernard discussed the power and potential of interracial friendships through the historical lens of Van Vechten’s role as patron during this early 20th-century period.

“There was really no one like Van Vechten,” said Bernard, whose book Carl Van Vechten: A Life in Black and White will be published by Yale University press later this year. “He did everything he could to promote black artists, he wrote articles and he had parties. He was a genius at throwing parties.” She described how the relationships formed in his apartment, at a time when clubs and other social venues were highly segregated, set the stage for the patronage of many influential artists, from Langston Hughes to Zora Neale Hurston.

Videos of full lectures are available at our website.

In April, a year of concerts in honor of retiring music professor Luis Battle culminated in a final concert featuring musicians from Marlboro Music. A touring quintet consisting of Benjamin Beilman (violin, pictured left), Veronika Eberle (violin, pictured right), Beth Guterman (viola), Yura Lee (viola) and Judith Serkin (cello) performed a program of Mozart, Haydn and Dvorak.

In April, a year of concerts in honor of retiring music professor Luis Battle culminated in a final concert featuring musicians from Marlboro Music. A touring quintet consisting of Benjamin Beilman (violin, pictured left), Veronika Eberle (violin, pictured right), Beth Guterman (viola), Yura Lee (viola) and Judith Serkin (cello) performed a program of Mozart, Haydn and Dvorak.

Worthy of Note

Marlboro congratulates photography professor John Willis for receiving a fellowship award from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in April. John is one of 180 scholars, artists and scientists chosen from almost 3,000 applicants across the country. His application included work from his 2010 book, Views from the Reservation (Potash Hill, Winter 2011), as well as his 2002 Recycled Realities (Potash Hill, Summer 2001), in addition to other endeavors. John plans to use the award to continue pursuing artistic projects that integrate his work at Marlboro with the youth programs he has helped establish, the In-Sight Photography Project in Brattleboro and the Exposures cross-cultural youth arts program.

Marlboro congratulates photography professor John Willis for receiving a fellowship award from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in April. John is one of 180 scholars, artists and scientists chosen from almost 3,000 applicants across the country. His application included work from his 2010 book, Views from the Reservation (Potash Hill, Winter 2011), as well as his 2002 Recycled Realities (Potash Hill, Summer 2001), in addition to other endeavors. John plans to use the award to continue pursuing artistic projects that integrate his work at Marlboro with the youth programs he has helped establish, the In-Sight Photography Project in Brattleboro and the Exposures cross-cultural youth arts program.

Recently retired (but never slowing down) biology professor Bob Engel taught a class in ornithology this spring at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, a continuing education program for seniors in Brattleboro. Also featured this spring was anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson, discussing indigenous peoples of Latin America in the 21st century. These Marlboro faculty members continue a long tradition of sharing their scholarship with elder community members at Osher, including in recent years William Edelglass, Lynette Rummel, Amer Latif, Meg Mott and Geri Pittman de Batlle.

“I explore functional forms that reflect industrial traditions, seeking to make work that may be, in some way, indicative of the eminence of the owner,” writes ceramics professor Martina Lantin in an article in the March/April 2011 issue of Pottery Making Illustrated. Titled “A Crowning Achievement,” the article describes Martina’s inspiration and technique for creating “crown jars,” original designs that combine functionality with decorative qualities reminiscent of Wedgwood and other status-symbol ceramics of the early industrial era. “My crown jars are equally capable of holding the collected bounty of a batch of cookies or the ideas and aspirations of its owner.”

Anyone who has attended staff-faculty readings at the college has been delighted to learn that Marlboro’s president, Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, is also an accomplished poet. Last winter marked the publication of a fine book of poems by Ellen, Gone, in a limited edition from the acclaimed art book publisher Janus Press. Gone is illustrated with a lithograph by Janus founder Claire Van Vliet and includes 21 of Ellen’s poems printed on handmade paper from a mill in Maidstone, England.

Anyone who has attended staff-faculty readings at the college has been delighted to learn that Marlboro’s president, Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, is also an accomplished poet. Last winter marked the publication of a fine book of poems by Ellen, Gone, in a limited edition from the acclaimed art book publisher Janus Press. Gone is illustrated with a lithograph by Janus founder Claire Van Vliet and includes 21 of Ellen’s poems printed on handmade paper from a mill in Maidstone, England.

“Where else is a nuclear disaster in the world’s only A-bombed country more potent than in the world’s first A-bombed city?” asked Andrew Tanabe ’12, reporting from his World Studies Program internship in Hiroshima, Japan. He was working at the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, doing research and translation as well as helping to create a model “Peace Culture” that includes a clean energy economy and local food systems. In the wake of the nuclear disaster in northeast Japan, he was surprised to learn that Japanese citizens do not often connect nuclear weapons with nuclear power. “Interestingly, I think this sentiment is particularly strong in Hiroshima,” Andrew said.

“As a research tool, and a way to make some friends, I have been learning my way around a root of ginger, a clove of garlic, a spoon, a wok and some fatty pork,” said World Studies Program student Zack Chilcote ’13. He is spending a year in Beijing, teaching English at a Montessori school and researching the social impacts of China’s “one child” policy. He hopes that the school will provide guanxi (connections) for his research, but he’s finding the quickest way to meet people is to cook for them. “Research gives me the ability to say something that perhaps other people have not thought of before, and then actually explore it until it becomes real to me.”

Brenda Foley, theater professor and director of the World Studies Program, presented a paper in May at an interdisciplinary meeting in Warsaw called “Probing the Boundaries, Making Sense of Pain.” In the paper, which combines theory from the fields of disability and performance studies, Brenda explores how performance can be used to disrupt a socially constructed public image of disability that denies the reality of visible pain. “Culturally we perpetuate a hierarchy of disability according to visible difference,” she said. “We like our disabilities to be neat and tidy, not messy, sloppy, ugly or contorted in pain. But the potential exists in performance to blur that societal inscription.”

Not everyone celebrates their birthday with a terzetto from Mozart’s Magic Flute and a fountain of molten chocolate. But then, not everyone is retired language professor Edmund Brelsford. In March the venerable Marlboro Recorder Workshop, founded by Edmund, celebrated its 47th-anniversary concert season and Edmund’s 80th with a concert in Ragle Hall. The ensemble presented vocal and instrumental music of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the baroque and classical periods. Their concert paid homage to the late Blanche Honegger Moyse, as well as to retiring Marlboro colleague Luis Batlle, and was followed by a reception with cake and, yes, molten chocolate for dipping strawberries.

Not everyone celebrates their birthday with a terzetto from Mozart’s Magic Flute and a fountain of molten chocolate. But then, not everyone is retired language professor Edmund Brelsford. In March the venerable Marlboro Recorder Workshop, founded by Edmund, celebrated its 47th-anniversary concert season and Edmund’s 80th with a concert in Ragle Hall. The ensemble presented vocal and instrumental music of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the baroque and classical periods. Their concert paid homage to the late Blanche Honegger Moyse, as well as to retiring Marlboro colleague Luis Batlle, and was followed by a reception with cake and, yes, molten chocolate for dipping strawberries.

Those who read the last issue of Potash Hill (Winter 2011) will remember Sari Brown’s ’11 field research on gender and religion in Bolivia. This spring, Sari returned to Bolivia with anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson, supported by an Aron Grant, to look beyond discursive methods of documenting life in and around La Paz. They created artwork, recorded street sounds, took series of photos in stop-motion style and brought back food and garments from Bolivia’s rich material culture. “It was really interesting for me to go back and try to be conscientious about taking things in on a more bodily, sensorial level and looking for nondiscursive forms of meaning and communicating,” said Sari.

During winter break, Emily Mente ’11 joined students from across the country for a week of workshops and meetings in New York City called Feminist Winter Term. Initiated by Soapbox Inc., the program brings young feminists together to broaden their horizons and show them what kinds of jobs are available with a gender studies degree. “It really gave us an idea of what the feminist landscape of New York City looks like,” said Emily, who even tagged along with one of the organizers for a meeting with Gloria Steinem. “I was so star-struck,” she said.

During winter break, Emily Mente ’11 joined students from across the country for a week of workshops and meetings in New York City called Feminist Winter Term. Initiated by Soapbox Inc., the program brings young feminists together to broaden their horizons and show them what kinds of jobs are available with a gender studies degree. “It really gave us an idea of what the feminist landscape of New York City looks like,” said Emily, who even tagged along with one of the organizers for a meeting with Gloria Steinem. “I was so star-struck,” she said.

Philosophy professor William Edelglass writes, “It seems to be a natural development in all literate societies, and in many nonliterate societies as well, to ask difficult questions about the fundamental nature of reality, about what it is to be human, about what constitutes a good life, about the nature of beauty and about how we can know any of these things.” William and colleague Jay L. Garfield edited The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy (ISBN 978-0-19-532899-8), published by Oxford this year, co-authoring the introduction and the chapter on Indo-Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. His recent publications also include a bibliographic essay on Buddhist philosophy for the Oxford Bibliographies Online.

As if being dean of students and hosting a nationally syndicated radio show is not keeping him busy enough, Ken Schneck went ahead and got elected to the Brattleboro Town Selectboard with 59 percent of the vote in March. His goal, as always, is to invite as many voices to contribute to town discussions and decisions as possible. “Our town government has not yet embraced social media,” said Ken. “In fact, we’ve barely said hello to electronic media. I want to create different avenues of participation for Brattleboro citizens to be heard, diversifying the communication stream as much as possible. Also, bringing some levity to the process? Not such a bad thing.”

As if being dean of students and hosting a nationally syndicated radio show is not keeping him busy enough, Ken Schneck went ahead and got elected to the Brattleboro Town Selectboard with 59 percent of the vote in March. His goal, as always, is to invite as many voices to contribute to town discussions and decisions as possible. “Our town government has not yet embraced social media,” said Ken. “In fact, we’ve barely said hello to electronic media. I want to create different avenues of participation for Brattleboro citizens to be heard, diversifying the communication stream as much as possible. Also, bringing some levity to the process? Not such a bad thing.”

“I’m off getting some fresh, new stories and insights to enliven my African Politics course this fall,” Lynette Rummel wrote from her adventures in Mali, where she spent three weeks of spring sabbatical. Lynette plans to use Mali as a case study country, to explore and examine the more general trends and patterns that she presents in class. “I’ve never been to Mali before, so it will make it new and exciting to reconsider common arguments and larger contours in a new and different light. For example, I wonder if many Americans are aware of our involvement in this country as a front against, you guessed it, al Qaida in the Maghreb.”

Apparently not one to sit still for long, art professor Felicity Ratté spent her 2010–11 sabbatical year studying Islamic art and architecture around the Mediterranean region. Starting last August, Felicity explored Spain, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Turkey and Bulgaria, finally ending her travels in Venice. She photographed vaulted domes and minarets from Kairouan to Kurdistan in an effort to better understand how medieval city-dwellers used their urban landscape. “Now I need to sit down and make some sense out of it all,” Felicity said, but again, sitting is not her strength. In May she presented preliminary findings in a conference paper titled “The celebrated city in the Mediterranean: possibilities for comparison between Florence and Cairo, c. 1300,” in Corfu.

Be sure to get the latest scoop on Potash Hill at these sites:

Commencement 2011

A gray and rainy day did not dissuade hundreds of graduating seniors, family, friends and community members from gathering in Persons Auditorium on May 15 to celebrate Marlboro’s 64th commencement. The class of 2011 included 69 graduates, completing courses of study ranging from psycholinguistics to food studies, from jazz history to combinatorics. President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell marked changes in the world since the class started their intellectual journey at Marlboro four years ago, as well as profound changes in the students themselves. Senior speaker Jonathan Jones reminded students of the impermanence of failures and the permanence of bonds formed on Potash Hill. An honorary degree was conferred upon Claudine Brown, assistant secretary for education and access for the Smithsonian Institution, who encouraged the graduates to embrace change. John Scagliotti, Emmy award–winning filmmaker, television producer and radio broadcaster, also received an honorary degree in recognition of his efforts to celebrate the LGBT community’s contribution to culture and politics. Reverend R. Dewitt Mallary Jr., father of trustee Peter Mallary ’76 and grandfather of Rebecca Mallary ’11, offered the valediction, and the event was underscored with jazz guitar duets played by Zach Pearson ’11 and music professor Stan Charkey.

From President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s address

From President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s address

Who are you, now, today? Research tells us that the college years are that precious time to think, to create, to explore and to become, when a person’s identity is forged. Influential teachers challenged, then validated you. You learned from your peers—outside the classroom and on trips. You came with ideas and changed them. You went through the crucible of confusion and change—exploring your beliefs, your differences and biases, even suffering the loss of loved ones—to emerge with a stronger sense of self. You know more about what you are capable of, how convincing you are, how strong, what lasts. You know through experience what educational philosopher John Dewey said: “The self is not something ready-made, but something in continuous formation through choice of action.”

From Jonathan Jones’ senior address

From Jonathan Jones’ senior address

Every one of us walking across this stage today is a creator of something magnificent, something born of ether and electricity and the frustration of failure after failure. We created this thing we call Plan; so why not the other things we seek? I believe we already have. We search for love, and yet if you glance ever so briefly around this room you will see no fewer than 20 people who love you. We search for understanding, after spending four years learning how to have it, and to give it. As far as family, I challenge anyone to spend even one week on this hill and tell me we aren’t one.

From the honorary degree citation for Claudine Brown

For more than 30 years, you have worked within the museum and philanthropy worlds to promote education that is both hands-on and multisensory. You have said that “museums create communities” and, as the director of education at the Smithsonian Institution, you are creating a new community of learning for students of all ages.… You are asking, “What does it look like to be the nation’s museum in the 21st century, using all the tools that exist now to reach people?”

From Claudine Brown’s address

From Claudine Brown’s address

I have worked with smart people, crazy people, brave and defiant people, insecure people who were willing to put aside their fears for the benefit of others, shy people who chose to assert themselves when they were most needed and risk-taking young people who have grown into wise leaders; and I learned from them all. This work-life, that has been so very fulfilling for me, did not come about because I had an orderly plan. It has been about leaving my comfort zone and embracing discomfort—taking risk and embracing change. It has been about teaching and learning.… It is highly likely that you will have more than one great idea. Give time and attention to your dreams and goals. Don’t just talk about them, do something about them. Others may achieve similar goals before you, but your interpretation and implementation of that goal will be unique. If you care about it, do something every day to make it real.

From the valediction by Reverend Mallary

From the valediction by Reverend Mallary

The end is near, and I don’t mean the rapture on May 21st…. May you leave this place with affection, but even more with thanks for doors it has opened for you, for friends you have made, and for the intellectual tools you have acquired. May you find ways to use your gifts, not simply for gain or for pleasure, but for justice and compassion near and far. And whatever your particular spiritual resources, your particular religious or philosophical convictions, may your compass point true north.

For full transcripts of addresses and citations, a list of 2011 graduates and their Plans of Concentration as well as photos and videos, go to Marlboro's Commencement 2011 site.

Academic Prizes

The Rebecca Willow Prize, established in 2008 in memory of Rebecca Willow, class of 1995, is awarded to students whose presence bring personal integrity and kindness to the community and who unite an interest in human history and culture with a passion for the natural world. Casey Chalbeck and Amanda Whiting

The Rebecca Willow Prize, established in 2008 in memory of Rebecca Willow, class of 1995, is awarded to students whose presence bring personal integrity and kindness to the community and who unite an interest in human history and culture with a passion for the natural world. Casey Chalbeck and Amanda Whiting

The Audrey Alley Gorton Award is given in memory of Audrey Gorton, Marlboro alumna and member of the faculty for 33 years, to the student who best reflects the Gorton qualities of: passion for reading, independence of critical judgment, fastidious attention to matters of style and a gift for intelligent conversation. Emma Goldhammer

The Hilly van Loon Prize, established by the class of 2000 in honor of Hilly van Loon, Marlboro class of 1962 and staff member for 23 years, is given to the seniors who best reflect Hilly’s wisdom, compassion, community involvement, quiet dedication to the spirit of Marlboro College, joy in writing and celebration of life. Eric Toldi and Kelly Ahrens

The William Davisson Prize, created by the Town Meeting Selectboard and named in honor of Will Davisson, who served as a faculty member for 18 years and as a trustee for 22 years, is awarded to one or more students for extraordinary contributions to the Marlboro community. Anna Knecht and Sarah Verbil

The Ryan Larsen Memorial Prize was established in 2006 in memory of Ryan Jeffrey Larsen, who felt transformed by the opportunities to learn and grow within the embrace of the Marlboro College community. It is awarded annually to juniors or seniors who best reflect Ryan’s qualities of philosophical curiosity, creativity, compassion and spiritual inquiry. Michael Thompson and Sari Brown

The Ryan Larsen Memorial Prize was established in 2006 in memory of Ryan Jeffrey Larsen, who felt transformed by the opportunities to learn and grow within the embrace of the Marlboro College community. It is awarded annually to juniors or seniors who best reflect Ryan’s qualities of philosophical curiosity, creativity, compassion and spiritual inquiry. Michael Thompson and Sari Brown

The Helen W. Clark Prize is awarded by the visual arts faculty for the best Plans of Concentration in the fine arts. Sophie Mueller and Lex Kosieradzki

The Sally and Valerio Montanari Theater Prize is awarded annually to a graduating senior who has made the greatest overall contribution to the pursuit of excellence in theater production. Elizabeth Hull

The Sally and Valerio Montanari Theater Prize is awarded annually to a graduating senior who has made the greatest overall contribution to the pursuit of excellence in theater production. Elizabeth Hull

The Dr. Loren C. Bronson Award for Excellence in Classics, established by the family of Loren Bronson, class of 1973, is awarded to encourage undergraduate work in classics. Emily Kimble and Amanda Whiting

The Roland W. Boyden Prize is given by the humanities faculty to students who have demonstrated excellence in the humanities. Roland Boyden was a founding faculty member of the college, acting president, dean and trustee. Eric Breeden and Michael Mirer

The Roland W. Boyden Prize is given by the humanities faculty to students who have demonstrated excellence in the humanities. Roland Boyden was a founding faculty member of the college, acting president, dean and trustee. Eric Breeden and Michael Mirer

The Buck Turner Prize is awarded to a student who demonstrates excellence in the natural sciences, who uses interdisciplinary approaches, and who places his or her work in the context of larger questions. Chrissy Raudonis

The Freshman/Sophomore Essay Prize is given annually for the best essay written for a Marlboro course. Kathryn Lyon; honorable mention, Adam Halwitz

The Freshman/Sophomore Essay Prize is given annually for the best essay written for a Marlboro course. Kathryn Lyon; honorable mention, Adam Halwitz

The Robert H. MacArthur Prize was established in 1973 in memory of Robert MacArthur, class of 1951, and recently rededicated to Robert and also to John and to John and Robert’s parents, John and Olive MacArthur, who founded the science program at Marlboro College. The contest for the prize is in the form of a question or challenge offered to the entire student community. Thea Cabreros; Eric Joyce and Lex Kosieradzki; Tristan Pease

The Robert E. Engel Award in honor of Bob Engel, Marlboro faculty member for 36 years, is given to students who display Bob’s sense of wonder for the natural world and his keen powers of observation and inquiry as a natural historian. Kathryn Lyon and Clare Riley

For more on Bob’s legacy, see "Evolutionary Tree."