Fall 2018

Editor’s Note

On page 1, junior Anna Morrisey describes how Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” teaches the reader “to live as part and parcel of the world,” to find the sacred balance between self and other. Building on last issue’s introduction of the Center for Experiential Learning and Global Engagement, this issue of Potash Hill has many such lessons, many ways that Marlboro students have gone beyond their studies to find their “self” in the world.

For example, students traveling to Yellowstone National Park last March were given the opportunity to slow down and be a part of the Rocky Mountains landscape in winter, giving many of them new perspectives on ecology and community. “In a world where a thousand things are constantly demanded of us from technology and social media, that open and focused space is an invitation to connect to ecosystems much larger than us,” says Adam Katrick, Outdoor Program director, who led the trip.

Closer to home, other students are finding new ways to include community governance in their course of study, to balance their individual academic interests with the common good. From recent graduate Andrew Smith Domzal’s exploration of the existential black experience to alumna Jessica Flannery’s intrepid efforts to deliver public health programs in remote, war-torn areas of Africa, this issue brims with diverse lessons about how to be “of the world.”

Despite Adam’s understandable caution about social media mentioned above, I want to take this opportunity to personally invite every Marlboro community member to be part of the world of Branch Out, Marlboro’s very own virtual community. Get connected, find old friends and meet new ones, gain career advice and share memories. And if you have your own lessons about finding the sacred balance between self and other, or any other reactions to this issue of Potash Hill, I hope you’ll share them with me at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

—Philip Johansson

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Alumni Director: Maia Segura ’91

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Richard Smith

Staff Photographers: Clayton Clemetson ’18, Sam Harrison ’20, and David Teter ’19

Design: New Ground Creative

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: Blue Clouds, by Cathy Osman. One of several works by retired visual arts faculty Cathy Osman and Tim Segar that were reproduced and inserted in each diploma handed out to graduates at commencement 2018. Learn more about commencement.

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

“This formative experience of leaving family and coming into a new community is something that I think we miss a lot in our Western culture,” says former Outdoor Program director Randy Knaggs ’94. “I think it’s important to pause and ponder what those transitions mean, and be thoughtful about it.” Of course Randy’s referring to Marlboro’s stellar Bridges orientation program, which puts new students together with experienced student leaders to learn about community before they come to campus. We know it’s “so 2017,” but it’s worth sharing the video about last year’s Bridges trips filmed and edited by Patrick Kennedy ’09 (pictured, second from right).

Up Front

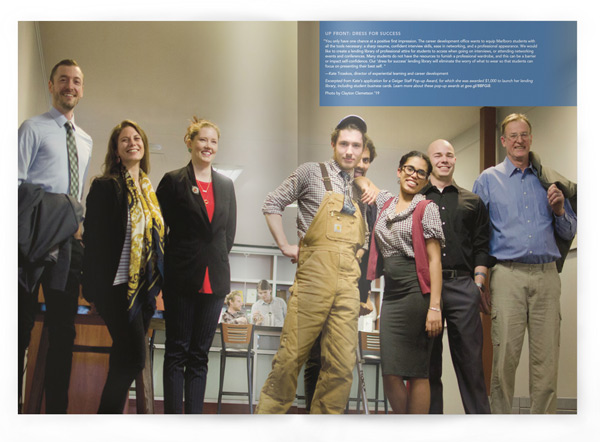

Dress for Success

“You only have one chance at a positive first impression. The career development office wants to equip Marlboro students with all the tools necessary: a sharp resume, confident interview skills, ease in networking, and a professional appearance. We would like to create a lending library of professional attire for students to access when going on interviews, or attending networking events and conferences. Many students do not have the resources to furnish a professional wardrobe, and this can be a barrier or impact self-confidence. Our ‘dress for success’ lending library will eliminate the worry of what to wear so that students can focus on presenting their best self. “

—Kate Trzaskos, director of experiential learning and career development

Excerpted from Kate’s application for a Geiger Staff Pop-up Award, for which she was awarded $1,000 to launch her lending library, including student business cards. Learn more about these pop-up awards.

Photo by Clayton Clemetson ’19

Clear Writing

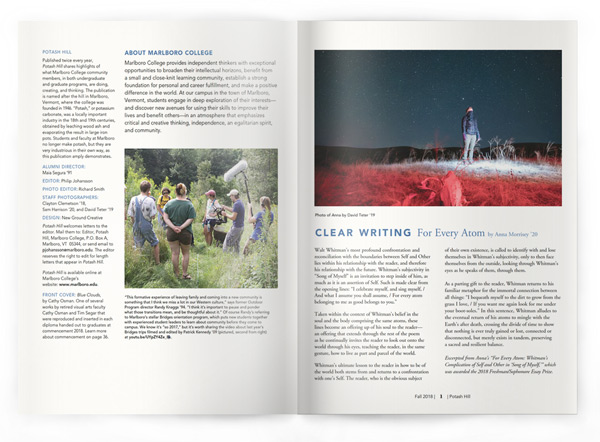

For Every Atom

by Anna Morrisey ’20

Walt Whitman’s most profound confrontation and reconciliation with the boundaries between Self and Other lies within his relationship with the reader, and therefore his relationship with the future. Whitman’s subjectivity in “Song of Myself” is an invitation to step inside of him, as much as it is an assertion of Self. Such is made clear from the opening lines: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

Taken within the context of Whitman’s belief in the soul and the body comprising the same atoms, these lines become an offering up of his soul to the reader— an offering that extends through the rest of the poem as he continually invites the reader to look out onto the world through his eyes, teaching the reader, in the same gesture, how to live as part and parcel of the world.

Whitman’s ultimate lesson to the reader in how to be of the world both stems from and returns to a confrontation with one’s Self. The reader, who is the obvious subject of their own existence, is called to identify with and lose themselves in Whitman’s subjectivity, only to then face themselves from the outside, looking through Whitman’s eyes as he speaks of them, through them.

Whitman’s ultimate lesson to the reader in how to be of the world both stems from and returns to a confrontation with one’s Self. The reader, who is the obvious subject of their own existence, is called to identify with and lose themselves in Whitman’s subjectivity, only to then face themselves from the outside, looking through Whitman’s eyes as he speaks of them, through them.

As a parting gift to the reader, Whitman returns to his familiar metaphor for the immortal connection between all things: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.” In this sentence, Whitman alludes to the eventual return of his atoms to mingle with the Earth’s after death, crossing the divide of time to show that nothing is ever truly gained or lost, connected or disconnected, but merely exists in tandem, preserving a sacred and resilient balance.

Excerpted from Anna’s “For Every Atom: Whitman’s Complication of Self and Other in ‘Song of Myself,’” which was awarded the 2018 Freshman/Sophomore Essay Prize.

Photo of Anna by David Teter ’19

Letters

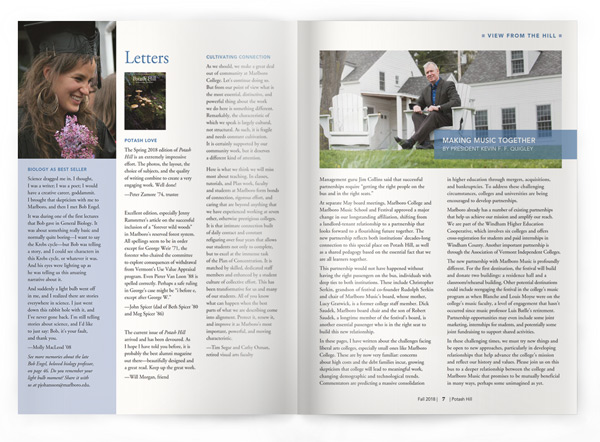

Potash Love

Potash Love

The Spring 2018 edition of Potash Hill is an extremely impressive effort. The photos, the layout, the choice of subjects, and the quality of writing combine to create a very engaging work. Well done!

—Peter Zamore ’74, trustee

Excellent edition, especially Jenny Ramstetter’s article on the successful inclusion of a “forever wild woods” in Marlboro’s reserved forest system. All spellings seem to be in order except for George Weir ’71, the forester who chaired the committee to explore consequences of withdrawal from Vermont’s Use Value Appraisal program. Even Pieter Van Loon ’88 is spelled correctly. Perhaps a safe ruling in George’s case might be “i before e, except after George W.” —John Spicer (dad of Beth Spicer ’80 and Meg Spicer ’86)

The current issue of Potash Hill arrived and has been devoured. As I hope I have told you before, it is probably the best alumni magazine out there—beautifully designed and a great read. Keep up the great work.

—Will Morgan, friend

Cultivating Connection

As we should, we make a great deal out of community at Marlboro College. Let’s continue doing so. But from our point of view what is the most essential, distinctive, and powerful thing about the work we do here is something different. Remarkably, the characteristic of which we speak is largely cultural, not structural. As such, it is fragile and needs constant cultivation. It is certainly supported by our community work, but it deserves a different kind of attention.

Here is what we think we will miss most about teaching. In classes, tutorials, and Plan work, faculty and students at Marlboro form bonds of connection, rigorous effort, and caring that are beyond anything that we have experienced working at seven other, otherwise prestigious colleges. It is that intimate connection built of daily contact and constant refiguring over four years that allows our students not only to complete, but to excel at the immense task of the Plan of Concentration. It is matched by skilled, dedicated staff members and enhanced by a student culture of collective effort. This has been transformative for us and many of our students. All of you know what can happen when the best parts of what we are describing come into alignment. Protect it, renew it, and improve it as Marboro’s most important, powerful, and moving characteristic.

—Tim Segar and Cathy Osman, retired visual arts faculty

Biology as Best Seller

Science dragged me in. I thought, I was a writer; I was a poet; I would have a creative career, goddammit. I brought that skepticism with me to Marlboro, and then I met Bob Engel. It was during one of the first lectures that Bob gave in General Biology.

It was about something really basic and normally quite boring—I want to say the Krebs cycle—but Bob was telling a story, and I could see characters in this Krebs cycle, or whatever it was. And his eyes were lighting up as he was telling us this amazing narrative about it.

And suddenly a light bulb went off in me, and I realized there are stories everywhere in science. I just went down this rabbit hole with it, and I’ve never gone back. I’m still telling stories about science, and I’d like to just say: Bob, it’s your fault, and thank you.

—Molly MacLeod ’08 (pictured, right)

See more memories about the late Bob Engel, beloved biology professor. Do you remember your light bulb moment? Share it with us at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

View from the Hill

Making Music Together

By President Kevin F. F. Quigley

Management guru Jim Collins said that successful partnerships require “getting the right people on the bus and in the right seats.”

At separate May board meetings, Marlboro College and Marlboro Music School and Festival approved a major change in our longstanding affiliation, shifting from a landlord-tenant relationship to a partnership that looks forward to a flourishing future together. The new partnership reflects both institutions’ decades-long connection to this special place on Potash Hill, as well as a shared pedagogy based on the essential fact that we are all learners together.

This partnership would not have happened without having the right passengers on the bus, individuals with deep ties to both institutions. These include Christopher Serkin, grandson of festival co-founder Rudolph Serkin and chair of Marlboro Music’s board, whose mother, Lucy Gratwick, is a former college staff member. Dick Saudek, Marlboro board chair and the son of Robert Saudek, a longtime member of the festival’s board, is another essential passenger who is in the right seat to build this new relationship.

In these pages, I have written about the challenges facing liberal arts colleges, especially small ones like Marlboro College. These are by now very familiar: concerns about high costs and the debt families incur, growing skepticism that college will lead to meaningful work, changing demographic and technological trends. Commentators are predicting a massive consolidation in higher education through mergers, acquisitions, and bankruptcies. To address these challenging circumstances, colleges and universities are being encouraged to develop partnerships.

Marlboro already has a number of existing partnerships that help us achieve our mission and amplify our reach. We are part of the Windham Higher Education Cooperative, which involves six colleges and offers cross-registration for students and paid internships in Windham County. Another important partnership is through the Association of Vermont Independent Colleges.

The new partnership with Marlboro Music is profoundly different. For the first destination, the festival will build and donate two buildings: a residence hall and a classroom/rehearsal building. Other potential destinations could include reengaging the festival in the college’s music program as when Blanche and Louis Moyse were on the college’s music faculty, a level of engagement that hasn’t occurred since music professor Luis Batlle’s retirement. Partnership opportunities may even include some joint marketing, internships for students, and potentially some joint fundraising to support shared activities.

In these challenging times, we must try new things and be open to new approaches, particularly in developing relationships that help advance the college’s mission and reflect our history and values. Please join us on this bus to a deeper relationship between the college and Marlboro Music that promises to be mutually beneficial in many ways, perhaps some unimagined as yet.

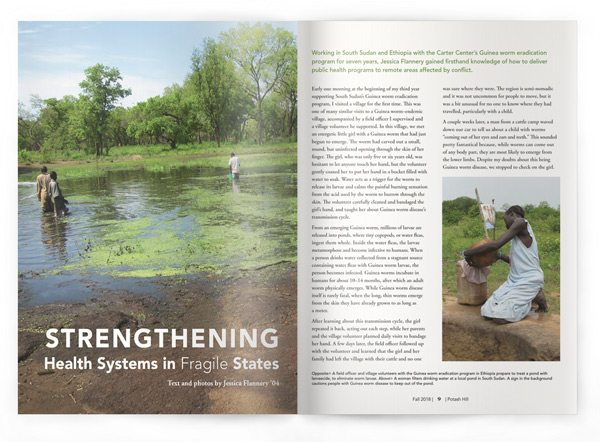

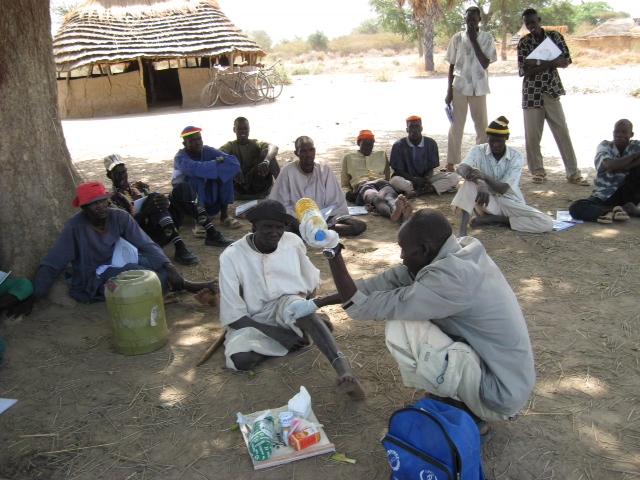

Strengthening Health Systems in Fragile States

Text and photos by Jessica Flannery ’04

Working in South Sudan and Ethiopia with the Carter Center’s Guinea worm eradication program for seven years, Jessica Flannery gained firsthand knowledge of how to deliver public health programs to remote areas affected by conflict.

Early one morning at the beginning of my third year supporting South Sudan’s Guinea worm eradication program, I visited a village for the first time. This was one of many similar visits to a Guinea worm–endemic village, accompanied by a field officer I supervised and a village volunteer he supported. In this village, we met an energetic little girl with a Guinea worm that had just begun to emerge. The worm had carved out a small, round, but uninfected opening through the skin of her finger. The girl, who was only five or six years old, was hesitant to let anyone touch her hand, but the volunteer gently coaxed her to put her hand in a bucket filled with water to soak. Water acts as a trigger for the worm to release its larvae and calms the painful burning sensation from the acid used by the worm to burrow through the skin. The volunteer carefully cleaned and bandaged the girl’s hand, and taught her about Guinea worm disease’s transmission cycle.

Early one morning at the beginning of my third year supporting South Sudan’s Guinea worm eradication program, I visited a village for the first time. This was one of many similar visits to a Guinea worm–endemic village, accompanied by a field officer I supervised and a village volunteer he supported. In this village, we met an energetic little girl with a Guinea worm that had just begun to emerge. The worm had carved out a small, round, but uninfected opening through the skin of her finger. The girl, who was only five or six years old, was hesitant to let anyone touch her hand, but the volunteer gently coaxed her to put her hand in a bucket filled with water to soak. Water acts as a trigger for the worm to release its larvae and calms the painful burning sensation from the acid used by the worm to burrow through the skin. The volunteer carefully cleaned and bandaged the girl’s hand, and taught her about Guinea worm disease’s transmission cycle.

From an emerging Guinea worm, millions of larvae are released into ponds, where tiny copepods, or water fleas, ingest them whole. Inside the water fleas, the larvae metamorphose and become infective to humans. When a person drinks water collected from a stagnant source containing water fleas with Guinea worm larvae, the person becomes infected. Guinea worms incubate in humans for about 10– 14 months, after which an adult worm physically emerges. While Guinea worm disease itself is rarely fatal, when the long, thin worms emerge from the skin they have already grown to as long as a meter.

After learning about this transmission cycle, the girl repeated it back, acting out each step, while her parents and the village volunteer planned daily visits to bandage her hand. A few days later, the field officer followed up with the volunteer and learned that the girl and her family had left the village with their cattle and no one was sure where they were. The region is semi-nomadic and it was not uncommon for people to move, but it was a bit unusual for no one to know where they had travelled, particularly with a child.

A couple weeks later, a man from a cattle camp waved down our car to tell us about a child with worms “coming out of her eyes and ears and teeth.” This sounded pretty fantastical because, while worms can come out of any body part, they are most likely to emerge from the lower limbs. Despite my doubts about this being Guinea worm disease, we stopped to check on the girl.

We were led to a little girl whose legs were covered in pustules, many with emerging worms. As the field officer slowly cleaned her legs, I realized that this little girl, who was in so much pain that she could barely walk, was the same girl who had been so lively just weeks before. She did not have worms coming out of eyes or ears or teeth, but she had worms coming from all over her body, nearly 25 altogether, most from her legs.

We were led to a little girl whose legs were covered in pustules, many with emerging worms. As the field officer slowly cleaned her legs, I realized that this little girl, who was in so much pain that she could barely walk, was the same girl who had been so lively just weeks before. She did not have worms coming out of eyes or ears or teeth, but she had worms coming from all over her body, nearly 25 altogether, most from her legs.

The field officer massaged out some of the worms, cleaned the sores with soap and water, used a topical antibiotic, made sure the girl was well bandaged, and taught her mother how to bandage her, as there was no volunteer in the camp. We made plans to return the next day with more supplies and to help residents select village volunteers. When we came back, less than 24 hours later, the girl was walking around outside her house, tentatively, but recovering.

Treating this little girl led to working with her family and community to put systems into place to keep people from becoming infected: preventing those with emerging worms from entering water, providing simple filters to remove the water fleas from drinking water, and teaching people how to use and care for the filters. We also located potentially infected water sources in the area and targeted them for treatment with a larvaecide. We were able to identify other people connected with the girl who had Guinea worm, leading us to other communities.

At the time of our visit, in 2009, transmission had been stopped in all but four countries: Mali, Ethiopia, Chad, and South Sudan. The program’s focus on a single result—stopping Guinea worm transmission—led us to implement a clear set of interventions in a responsive and flexible manner, based on the conditions on the ground. This was supported by strong national leadership, sufficient resources, and close connections with communities.

At the same time, this girl, who was treated largely by having her legs cleaned with soap and water, had no access to a health facility, clean water, or other basic infrastructure that supports health. As we worked in communities, people with many other illnesses—women with obstetric emergencies, children with malaria, adults with tuberculosis—were brought to me for treatment because they had no access to health services. I am not a medical doctor and there was little I could do.

At the same time, this girl, who was treated largely by having her legs cleaned with soap and water, had no access to a health facility, clean water, or other basic infrastructure that supports health. As we worked in communities, people with many other illnesses—women with obstetric emergencies, children with malaria, adults with tuberculosis—were brought to me for treatment because they had no access to health services. I am not a medical doctor and there was little I could do.

In Guinea worm eradication, I saw clearly just how possible it is to achieve health results when those results are focused and interventions are responsive, even in a complex, war-torn country with minimal infrastructure. It was just as clear that a health sector response to really improving health outcomes for all the people and communities we worked with would require the development of a sustainable health system.

For example, in the Guinea worm eradication program I worked with many staff who started out as field officers or village volunteers. One new field officer had trouble using a calculator and filling out, much less overseeing, reporting forms. Other staff teased him because he was slow in answering questions.

We worked together patiently, visiting volunteers and supervising villages. Other supervisors also supported him at times, offering different perspectives. He developed relationships with communities and leaders, and he worked diligently and constantly. After a while, when I visited his area, his volunteers were among the strongest and most motivated. In the communities he covered, effective filter use was high and community leaders were engaged. Eventually, he became a supervisor. Like many others I encountered, he was a living example of how capacity can be developed in an individual, and over time within a program and the system as a whole.

Working in this very successful program, I became interested in how whole health systems can be built within complex, conflict-impacted environments, often termed “fragile states.” In the final year of my doctoral program in public health, I worked as a consultant with the Global Financing Facility, a global partnership aiming to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and nutrition (RMNCAHN).

Working in this very successful program, I became interested in how whole health systems can be built within complex, conflict-impacted environments, often termed “fragile states.” In the final year of my doctoral program in public health, I worked as a consultant with the Global Financing Facility, a global partnership aiming to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and nutrition (RMNCAHN).

At the time, Liberia had just completed their national plan to improve RMNCAHN. One key question was how to build sustainable capacity for health systems management at the county level. Having experienced warand the Ebola epidemic, Liberia’s many years of technical assistance had often replaced capacity with foreign expertise, instead of developing local capacity. This happens largely because the success of a technical assistance agency is frequently equated with the quality of outputs, such as the number of reports submitted, often leading these agencies to do the local health management team’s work. In addition, “capacity development” is often used almost synonymously with training, or developing skills, while there are many other aspects to capacity such as the ability to draw on other people and to adapt to changing circumstances.

Working with Liberia’s Ministry of Health, we visited county health teams and helped to identify the challenges with health system management at the county level. We found that while staff had plenty of trainings, challenges persisted in structures, communication, adapting to difficult circumstances, and other aspects of capacity. These challenges called for a broader view of capacity development, drawing on a “complex adaptive systems” approach. This approach studies how different parts of a system impact each other in multiple different ways. A complex adaptive systems approach to capacity development looks at a range of aspects including relationships, integration of different parts of the system, and adaptability. This broader view aims to develop the capacity of the whole organization to sustain itself through staffing changes, conflict, and other shocks.

With the Ministry of Health, we developed a way to assess capacity using simulations and other practical tests, with the goal of allowing a technical assistance agency to be paid based on the county health team’s actual capacity instead of outputs. This way, the technical assistance agency can be flexible in figuring out ways to develop capacity more effectively and achieve results while developing actual capacity. We hope that this approach, which will be tested in the coming year, will help develop capacity that stays in place after technical assistance leaves.

This broader approach to health services helps fill in some of the gaps I saw while working in South Sudan: how can we move from supporting a single disease to supporting the whole system in a way that facilitates long-term change? It’s also an approach that is very much adapted to local context, allows for flexibility in implementation, and can be tested and adapted to solve ongoing challenges.

This broader approach to health services helps fill in some of the gaps I saw while working in South Sudan: how can we move from supporting a single disease to supporting the whole system in a way that facilitates long-term change? It’s also an approach that is very much adapted to local context, allows for flexibility in implementation, and can be tested and adapted to solve ongoing challenges.

In my work in fragile states like South Sudan and Liberia, I have found that clarity of goal, along with space to try out different approaches, is critical. It’s also important to account for interactions between different, but interconnected, pieces: different types of knowledge, systems for learning, and systems for adaptation. It’s about using an approach that isn’t prescriptive, that lets people at all levels try things out and learn from them. Ultimately, a sustainable health system is more about engaging in a process than finding a single approach.

Jessica Flannery worked for the Carter Center in South Sudan for over five years. In March of 2018, she received her doctor of public health degree from the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. She is currently a consultant with the Global Financing Facility and World Bank.

From Child Soldier to Graduate Student

From Child Soldier to Graduate Student

Garang Buk Buk, a former child soldier in South Sudan’s brutal civil war, is a shining example of Jessica’s argument for the power of effective capacity development. Defying the odds, Garang worked with the Guinea worm eradication program, saving up enough money to pay for his undergraduate education in Nairobi, Kenya. Now he has been accepted to Emory University for a master’s in development practice, with the goal of returning to South Sudan to better his community. Learn more about the New Jersey high school class that is supporting Garang’s graduate school efforts, and contribute at: gofundme.com/get-garang-to-emory.

Law and Order in North Africa  “My greatest hope is to see the establishment of stable political systems that exist to serve the needs of the citizens, rather than to perpetuate themselves and protect their own interests,” says Amelia Fanelli ’18 who focused her Plan on the politics of North African regimes. “In my opinion, any movement in this direction would be a positive development.” Although she had been drawn to politics and law since childhood, as a World Studies Program student Amelia did her internship in Tunisia, and became interested in the constitutions of North African nations. “After returning from Tunisia, I was unsure how I would shape my experiences into a piece of written work, and I found the answer through combining my interest in politics and North Africa with my interest in written law,” she says.

“My greatest hope is to see the establishment of stable political systems that exist to serve the needs of the citizens, rather than to perpetuate themselves and protect their own interests,” says Amelia Fanelli ’18 who focused her Plan on the politics of North African regimes. “In my opinion, any movement in this direction would be a positive development.” Although she had been drawn to politics and law since childhood, as a World Studies Program student Amelia did her internship in Tunisia, and became interested in the constitutions of North African nations. “After returning from Tunisia, I was unsure how I would shape my experiences into a piece of written work, and I found the answer through combining my interest in politics and North Africa with my interest in written law,” she says.

“A Thing of Beauty…”

Text and Photographs by Seth Harter

In the spring of 2017, Asian studies and history professor Seth Harter and Salvatore Annunziato ’18 traveled for two weeks in Japan, exploring the history and contemporary expression of craft through carpentry, toolmaking, and ceramics. They found the century-old folk art movement known as mingei to be still alive but challenged by the forces of industrialization and fine arts.

“Tingk, Tingk, Tingk”—a hammer meets anvil with just a sliver of spring steel between them. The most senior shokunin (craftsman) at the Hishika Saw Factory in Miki City, Japan, works in a windowless room. Seated on a low bench, he faces a wide mirror and a fluorescent tube light, both propped on the floor. Tea thermos, boombox, and sweat rag are all within easy reach.

He taps a blade, holds it up to the mirror and light, checks it for distortion, and taps again. The blade found its way here after being cut on a fully automated toothing machine and briefly polished on a grinder. Once the perfectly balanced blade leaves the shokunin’s hands, a pair of much younger workers—who also field phone calls and receive visitors—will insert it into a cedar handle and wrap it with rattan cord. They’ll oil the blade, sheath it in protective paper, and box it for shipping. The shokunin does not sign his work, does not embellish the blade, does not reject the mechanization of earlier steps of the production process, does not rush, does not slack, does not chat with visitors. His touch is the secret sauce, the inimitable and indispensable step that allows blades as thin as 1/100th of an inch to slice straight through wood rather than veer off plumb or buckle and break. His work is mingei.

During my visit to Japan with senior Salvatore Annunziato, our fieldwork built on a year’s worth of tutorial reading in the realm of Japanese aesthetics, centering on Yanagi Sōetsu’s provocative essays defining and promoting mingei, published in English under the title The Unknown Craftsman. Drawing on the work of the British artists and social critics William Morris and John Ruskin, Yanagi decried the toll industrialization was taking on handicrafts in Japan. In 1926, he joined forces with potters Bernard Leach, Hamada Shoji, and Kawai Kanjirō, who together coined the term mingei for the folk art ideal they wished to promote. Over the next decade, these artists establish both a magazine and a museum in Tokyo dedicated to the promotion of works they thought embodied this ideal.

In Yanagi’s view, the highest expression of beauty rests not in fine art, but in the humble, utilitarian objects made by anonymous craftsmen. The best of these works honor the nature of their raw materials in a fashion only possible when a skilled and sensitive hand responds to natural irregularities. Industrial products were soulless, homogenous, aesthetically dead, Yanagi claimed, while fine art tried too hard. In its quest for beauty, fine art became ensnared in self-consciousness, theory, and the expression of ego. Borrowing from Buddhism, Yanagi championed a nondual aesthetic: an organic beauty unconstrained by formal principles of beauty and ugliness. The mingei craftsman dwells in a state of mushin (no-mind), emboldened by the inherited power of tradition yet free to create new forms.

In the century since Yanagi first began to develop his aesthetic principles, industrialization in Japan has, of course, proceeded unchecked, and fine art of the Western, nonfunctional, conceptual variety has also flourished. One might expect that Yanagi’s craftsman would have little room left to maneuver. Salvatore and I went to Japan to consider in what ways Yanagi’s aesthetic continues to be relevant.

We found ceramist Kawai Kanjirō’s house on a quiet lane in the bustling Higashiyama district of Kyoto. Along with other pottery pilgrims, we came to gape at the scale of his eight-chamber noborigama (climbing kiln) and the unmistakable elegance of his ceramic work. While touring the grounds, however, we also learned about his disposition as a shokunin. During the war years, too old to serve in the army and unable to procure enough wood to fire his massive kiln, Kawai built furniture synthesizing Japanese and Micronesian traditions, and wrote essays exploring his indebtedness both to prior generations of craftsmen and to contemporary colleagues, critics, and consumers. His writings were later published under the title We Do Not Work Alone. Following Yanagi’s principles, Kawai refused to sign his work and initially declined his designation by the Japanese government as a Living National Treasure, a post-war system of recognition and support meant to enhance the status of crafts in the country. Rejecting this security, he drove himself to ever-greater levels of production and to an ever-expanding aesthetic vocabulary.

While Kawai’s legacy is borne mostly in the clay, fellow ceramist and Yanagi associate Hamada Shoji’s impact has been much broader. In 1925, when Hamada moved to the town of Mashiko, a few hours north of Tokyo, its small scale ceramics production was overshadowed by the older kiln sites in central Japan. Today the town is home to more than 300 ceramic artists, and smoke from the wood-fired kilns wreaths the surrounding hills. Hamada’s influence is everywhere: in his Reference Collection housed on the site of his former studio; in the provincial ceramics museum; in the larger galleries that feature, usually alone in Lucite cases, original Hamada pots; and in the ubiquitous glazing patterns he made famous—sugarcane stalks, abstract swirls, combed lines—decorating the work of his successors.

Craft is unquestionably alive and well in Mashiko. While there, Salvatore and I stayed at Furuki, home to the Mashiko Ceramics Arts Club. Three generations of the proprietor’s family spilled in and out of the compound, overseeing the firing of a collection of work made by a group of local retirees, training two American apprentices, providing studio space to neighboring amateurs, and teaching classes to student groups from Tokyo. But when I imagine Yanagi walking through Mashiko today, I picture him scowling. Mashiko is, from a mingei perspective, a victim of Hamada’s success.

The best contemporary potters in Mashiko, like Ken Matsuzaki, regularly exhibit their works in the top galleries of London and New York. Hamada originals are more likely to be found under the watchful eye of a museum guard or shop proprietor than filled with tea, perched on the edge of a workbench. Japan’s prosperity and love of ceramic arts have meant that Mashiko potters can make a good living, but they do so as individuals, as artists who sign their work, who promote distinct aesthetic brands. They’re a far cry from Yanagi’s innocent 16th-century farmer whose rice bowls were perfect for being untainted by too much aesthetic theory.

That pottery should have become more art than craft is perhaps, to a Western audience, no surprise. When we ventured to the Takenaka Carpentry Tools Museum in Kobe, however, we discovered that wood plane making, too, had undergone this dubious elevation. On approaching the serene villa housing the museum, perfectly adzed cypress doors parted noiselessly before us. An exhibit dedicated to the development of woodworking tools in Japan pays homage to the skills and travails of unknown craftsmen, but the culmination of the exhibit is a section called “Exquisite Works of Master Craftsmen,” where individual blades with poetic names bathe in spotlit glory. These tools may once have been used to build temple roofs and kitchen hearths, but now the grime of the whetstone and the oil of the shokunin’s fingers have been wiped from them and they have become fetishized examples of abstract beauty. The names of the foremost blade forgers are not only known and displayed, but are used almost like imperial reign titles to orient the viewer chronologically: such-and-such a blade is from the Chiyozuru Korehide era. In the next room, a model teahouse and a shoji (sliding lattice door) likewise showed us how utilitarian objects can, with sufficient skill, patience, and money, transcend the everyday and provoke in the viewer a distancing awe.

Back in neighboring Miki City, where we first met the saw factory shokunin, the president of the Tsunesaburo Plane Blade Company had other things to worry about. Uozumi Akio’s three sons had all rejected the chance to follow in their father’s footsteps. The market in Japan for traditional hand tools was contracting, and tool makers of Miki City were concerned that their best days might be behind them. Retooling, so to speak, would not be easy. The city’s fortunes were established in the 16th century when the ruler of the region, Nagaharu Bessho, surrendered to the unifier Hideyoshi Toyotomi. In exchange for Bessho’s head, Hideyoshi relocated to Miki a group of talented blacksmiths (prisoners of war from his campaigns in Korea) and granted tax remissions for local industry. Miki’s fame and fortune as Hardware City was insured for 400 years, but what lies ahead for this craft-driven industry?

Seated in an office stacked with whetstones, blades, orders, and invoices, Uozumi told us that future prosperity depended on extending the market for his wares overseas. He and his workers would have to be sensitive both to the characteristics of their metal—a mix of Hitachi blue paper steel and iron salvaged from 19th-century railroads and shipping enterprises—but also to the changing demands of their customers. In this disposition, the president of a major tool manufacturer showed how few steps removed he was from the thinking of a shokunin. Tsuensaburo Plane Blade Company would survive by producing planes that were beautiful, not to look at in a gallery but to pull across a plank of cedar. I could see Yanagi smiling.

Seth Harter is professor of Asian studies and history. He recently studied temple architecture and joinery in Kyoto and Nara, and apprenticed with renowned chair-maker Tak Yoshino in Kawaguchiko, Japan, during his spring 2018 sabbatical. His visit to Japan with Salvatore was made possible by support from an Aron Grant and the Endeavor Foundation.

Counter-Industrial Ceramics  Seth’s deep exploration of Asian craft traditions have inspired more than one visual arts student. “The mingei movement, a counter-industrial craft movement in the 1920s and ’30s, is interesting to me,” says senior Henry Robinson, who studies ceramics and drawing at Marlboro. “It’s about bringing ceramics and art to a wider audience through skills and traditions.” The utilitarian approach to craft appeals to Henry, who can usually be found in the ceramics studio perfecting his skills. “I don’t want to just emulate this movement but instead make something that’s a little more personal to me that can also be useful—not these high-art objects. It would be one thing to bring art to a lot of people, but it’s another to create things that are really interesting.” Learn more about Henry.

Seth’s deep exploration of Asian craft traditions have inspired more than one visual arts student. “The mingei movement, a counter-industrial craft movement in the 1920s and ’30s, is interesting to me,” says senior Henry Robinson, who studies ceramics and drawing at Marlboro. “It’s about bringing ceramics and art to a wider audience through skills and traditions.” The utilitarian approach to craft appeals to Henry, who can usually be found in the ceramics studio perfecting his skills. “I don’t want to just emulate this movement but instead make something that’s a little more personal to me that can also be useful—not these high-art objects. It would be one thing to bring art to a lot of people, but it’s another to create things that are really interesting.” Learn more about Henry.

Anti-Essentialism in Black Thought

By Andrew Smith Domzal ’18

Existentialist thought is useful when discussing race, because it discards any essential qualities that a person might have and focuses on lived experience. There is nothing essential about being a black person: black people are all unique and distinct. That being said, because of the historical conditions that we are born into and that shape us—because there have been social structures that judge black people in certain ways and the dominant culture holds essentialized views of black people—there is a shared experience of being black in the world.

Existentialist thought is useful when discussing race, because it discards any essential qualities that a person might have and focuses on lived experience. There is nothing essential about being a black person: black people are all unique and distinct. That being said, because of the historical conditions that we are born into and that shape us—because there have been social structures that judge black people in certain ways and the dominant culture holds essentialized views of black people—there is a shared experience of being black in the world.

In Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race, Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “We make up selves from a tool kit of options made available by our culture and society…. We do make choices, but we don’t determine the options among which we choose.”

We exist in a society that has a specific history, which determines our options. Black people are born into a world where being black has certain connotations affecting their being-in-the-world. They are seen as, and given an essence as, other. This is existentially insulting, and breeds resentment by subsuming any freedom to choose the self. Recently—among biologists, social activists, and progressives—many have accepted that race is a social construct rather than a fact of biology. However, realizing that race is a social construct does not remove any of its power in the world, nor does it lessen its effect on the black person’s life.

Even positive scripts about black essentialism and normativity have the potential to be problematic. In the case of the Black Power movement—turning the old script of self-hatred into a new script in which one asks to be respected as a black—Appiah writes, “Someone who takes autonomy seriously will want to ask whether we have not replaced one kind of tyranny with another. If I had to choose between Uncle Tom and Black Power, I would, of course, choose the latter. But I would like not to have to choose. I would like other options.”

In order to truly liberate black existence we must understand blackness as a shared way of existing and not as a requirement of specific action. Blackness should be as diverse as the human spectrum in terms of actions, interests, dress, and so forth. In the existentialist perspective, discarding essences while still understanding the power of social constructs to determine life can tell one much about the black experience.

This essay is excerpted and adapted from one section of Andrew’s Plan, which is titled “‘I am fully what I am’: Philosophy, literature, and the lived experience of race.” Andrew is now living in Leuven, Belgium, and is enrolled in a master’s program in philosophy at the Catholic University of Leuven.

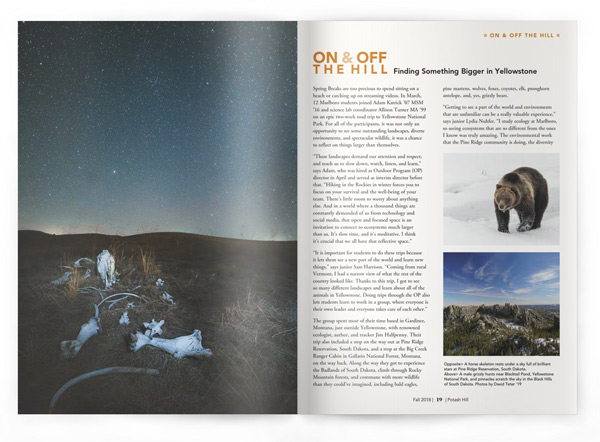

On and Off the Hill

Finding Something Bigger in Yellowstone

Spring Breaks are too precious to spend sitting on a beach or catching up on streaming videos. In March, 12 Marlboro students joined Adam Katrick ’07 MSM ’16 and science lab coordinator Allison Turner MA ’99 on an epic two-week road trip to Yellowstone National Park. For all of the participants, it was not only an opportunity to see some outstanding landscapes, diverse environments, and spectacular wildlife, it was a chance to reflect on things larger than themselves.

Spring Breaks are too precious to spend sitting on a beach or catching up on streaming videos. In March, 12 Marlboro students joined Adam Katrick ’07 MSM ’16 and science lab coordinator Allison Turner MA ’99 on an epic two-week road trip to Yellowstone National Park. For all of the participants, it was not only an opportunity to see some outstanding landscapes, diverse environments, and spectacular wildlife, it was a chance to reflect on things larger than themselves.

“These landscapes demand our attention and respect, and teach us to slow down, watch, listen, and learn,” says Adam, who was hired as Outdoor Program (OP) director in April and served as interim director before that. “Hiking in the Rockies in winter forces you to focus on your survival and the well-being of your team. There’s little room to worry about anything else. And in a world where a thousand things are constantly demanded of us from technology and social media, that open and focused space is an invitation to connect to ecosystems much larger than us. It’s slow time, and it’s meditative. I think it’s crucial that we all have that reflective space.”

“It is important for students to do these trips because it lets them see a new part of the world and learn new things,” says junior Sam Harrison. “Coming from rural Vermont, I had a narrow view of what the rest of the country looked like. Thanks to this trip, I got to see so many different landscapes and learn about all of the animals in Yellowstone. Doing trips through the OP also lets students learn to work in a group, where everyone is their own leader and everyone takes care of each other.”

The group spent most of their time based in Gardiner, Montana, just outside Yellowstone, with renowned ecologist, author, and tracker Jim Halfpenny. Their trip also included a stop on the way out at Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, and a stop at the Big Creek Ranger Cabin in Gallatin National Forest, Montana, on the way back. Along the way they got to experience the Badlands of South Dakota, climb through Rocky Mountain forests, and commune with more wildlife than they could’ve imagined, including bald eagles, pine martens, wolves, foxes, coyotes, elk, pronghorn antelope, and, yes, grizzly bears.

“Getting to see a part of the world and environments that are unfamiliar can be a really valuable experience,” says junior Lydia Nuhfer. “I study ecology at Marlboro, so seeing ecosystems that are so different from the ones I know was truly amazing. The environmental work that the Pine Ridge community is doing, the diversity of species and landscapes along the way, and the interactions with wildlife ecologists that I was able to experience absolutely tie into my studies.”

“Getting to see a part of the world and environments that are unfamiliar can be a really valuable experience,” says junior Lydia Nuhfer. “I study ecology at Marlboro, so seeing ecosystems that are so different from the ones I know was truly amazing. The environmental work that the Pine Ridge community is doing, the diversity of species and landscapes along the way, and the interactions with wildlife ecologists that I was able to experience absolutely tie into my studies.”

Like other OP expeditions through the years, the Yellowstone trip gave students the opportunity to engage with people they might not otherwise, like the Oglala Sioux community of the Pine Ridge Reservation or wildlife photographer Dan Hartman. It also provided many opportunities for leadership development—from planning menus to leading hikes or other activities— building skills and confidence that that will help students be more effective leaders for Bridges orientation trips, or in their future workplaces.

“The highlight of my trip was definitely staying in a Forest Service cabin in Gallatin National Forest on our way home,” says junior Claire O’Pray. “One of the days we were there four of us bush-whacked up the mountain that was behind the cabin. Mountains are my favorite thing in the world, and being confident enough to hike a mountain without a trail was really amazing. We also made split pea soup from scratch on a wood cookstove.”

“These expedition trips have so many experiences rolled into two intense weeks, that we rely on the participants’ individual skills, talents, and unique leadership styles to make it through each day,” says Adam. “We learn a lot about each other, have plentiful opportunities to share our skills with one another, and concurrently, grow and learn.” But for many of the participants, the highlight of the trip was seeing a male grizzly bear lumbering toward Blacktail Pond, at the northern end of the park. It was their last full day in the park, and they had not seen one yet—in fact they had been told it was extremely unlikely, even in Yellowstone—and there they were, 200 feet away and watching this huge bear break through the ice to find his next meal.

“That was pretty breathtaking, and so was simultaneously watching the look on Della’s face,” says Adam, referring to sophomore Della Dolcino. “She really wanted to see a bear, and was just in awe with tears of joy. To watch someone connect so profoundly to that bear, and that landscape…it was an amazing moment. We saw so much wildlife, but seeing that bear really just made us drop everything we were doing so we could set up our scopes and watch. All we could do was stand there and smile and shake our heads. It was spectacular.”

Adam asserts, and the students who joined him and Allison would surely concur, that the hands-on, experiential learning that takes place on OP trips like this one to Yellowstone is an essential counterpart to classroom work. He says, “When these trips are in their element, whether the Rocky Mountains or the Green Mountains, they provide the perfect environment for ‘aha’ moments and fuel for better learning.”

Creative Collaboration in Oaxaca

One of the most diverse states in Mexico, Oaxaca has a vibrant mix of indigenous cultures, cuisine, art, and folkloric traditions, with 17 distinct ethnic groups and more than 50 spoken dialects. For the spring semester, professors Rosario de Swanson (Spanish language and literature) and Brad Heck (video and film studies) co-taught a course titled Oaxaca: Cultural Exchange and Creative Collaboration, which culminated with a visit to the region in May.

One of the most diverse states in Mexico, Oaxaca has a vibrant mix of indigenous cultures, cuisine, art, and folkloric traditions, with 17 distinct ethnic groups and more than 50 spoken dialects. For the spring semester, professors Rosario de Swanson (Spanish language and literature) and Brad Heck (video and film studies) co-taught a course titled Oaxaca: Cultural Exchange and Creative Collaboration, which culminated with a visit to the region in May.

“Besides learning about the cultural diversity and history of Oaxaca, during the course of the semester our students communicated with students from the Oaxacan Learning Center,” says Rosario. This grassroots center provides academic tutoring and social-service support to low-income students from underserved urban neighborhoods and indigenous rural villages throughout the state of Oaxaca. “Through regular Skype sessions with their Oaxacan counterparts, they created a film script that was then shot during our two-week stay.”

Prior to their trip, the students organized a raffle as a fundraiser for the Oaxacan Learning Center, raising nearly $500, which they presented to the center on behalf of Marlboro College. “We hope to continue collaborating with this institution, which helps students serve as role models for their communities— their mission matches Marlboro’s spirit,” says Rosario.

Branch Out Makes Vital Connections

When admissions counselor Krystal Graybeal ’17 returned to Marlboro from a college fair last April, during the first warm, spring evening rain, she was too late to join biology professor Jaime Tanner and students who had been helping spotted salamanders cross South Road to their breeding sites. “I decided to do a late-night stroll with a friend, and ran into President KQ and his wife,” she wrote in the Branch Out “Marlboro Moments” group. “We all crept along South Road in a misty rain, ferrying the occasional critter to safety and out of the path of oncoming cars. It was my friend’s first time, though I’m pretty sure it will become a tradition!”

When admissions counselor Krystal Graybeal ’17 returned to Marlboro from a college fair last April, during the first warm, spring evening rain, she was too late to join biology professor Jaime Tanner and students who had been helping spotted salamanders cross South Road to their breeding sites. “I decided to do a late-night stroll with a friend, and ran into President KQ and his wife,” she wrote in the Branch Out “Marlboro Moments” group. “We all crept along South Road in a misty rain, ferrying the occasional critter to safety and out of the path of oncoming cars. It was my friend’s first time, though I’m pretty sure it will become a tradition!”

If you have not heard of Marlboro College Branch Out by now, you either have your head in the sand or you are rendered senseless by the phrases “online platform” or “virtual community.” Branch Out is the quintessential site for students, alumni, faculty, and friends to connect, engage, and support other members of the community. Since it was officially launched on May 1, with a festive presentation during the annual party for graduating students and alumni at the Marina Restaurant, there have been more than 400 new users and countless posts, groups started, and professional relationships kindled.

“If members use Branch Out to its potential, we get to find what others can offer to us in our personal or career pursuits; we could even get a lead on a sweet new job,” says Maia Segura ’91, director of alumni engagement, who helped Marlboro choose and implement the platform. “Ultimately, we get a better picture of what our community looks like, and we can build this rare community through stories about the truly life-changing nature of Marlboro College.”

Dubbed “Branch Out” by student focus group member Amelia Fanelli ’18, the new platform provides real-time opportunities for alumni to both benefit and give back through engagement opportunities, mentoring, events, and fundraising efforts. Similar platforms have been adopted at many colleges and universities worldwide over the last few years, and have been highly successful at increasing alumni engagement during particularly challenging times for institutions of higher education.

“I am particularly excited about the real potential for current students to be able to find mentors, internships, even jobs through this exclusive Marlboro online community,” says Kate Trzaskos, director of experiential learning and career development. “Branch Out provides a medium for us to connect with the rich, unique resources that we all bring to the table, to strengthen the community and help it to grow.” Learn more and log in at marlboro.edu/branch-out.

Who’s Who on Branch Out: Wouldn’t one of these make a nice connection?

- Corrin Meise-Munns ’09, land use planner at Pioneer Valley Planning Commission

- Alexander Hunter ’10, producer at CNN

- Nicole Hammond ’11, attorney advisor at the U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review

- Will Timpson ’09, front-end software engineer at Google

- Laura Frank ’92, producer and multiscreen technology specialist at Luminous FX n Dustin Pawlow ’15, field epidemiologist at Connecticut Department of Public Health

- Tom Good ’86, research biologist at NOAA Fisheries

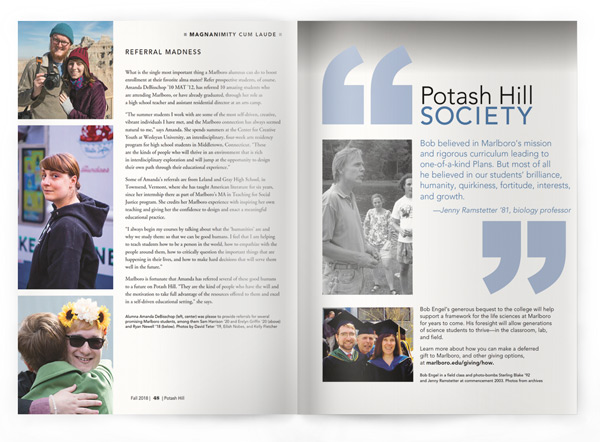

New Course Supports Community Governance

Although many students are drawn to Marlboro’s focus on community engagement and shared governance, some have found it difficult to integrate their community work with their course of study—until now. A new course called Community and Governance Colloquium, proposed by the Curriculum Committee last fall and piloted last spring semester, stands to make Marlboro’s shared governance model a more deeply integrated part of a Marlboro education.

Although many students are drawn to Marlboro’s focus on community engagement and shared governance, some have found it difficult to integrate their community work with their course of study—until now. A new course called Community and Governance Colloquium, proposed by the Curriculum Committee last fall and piloted last spring semester, stands to make Marlboro’s shared governance model a more deeply integrated part of a Marlboro education.

“There are so many shared skills gained by designing your own education and by having a voice in governing the campus,” says dance professor Kristin Horrigan, a member of the Curriculum Committee who is co-teaching the course this fall. “But students who come in excited about Town Meeting, committees, and community leadership roles were telling us that they had a hard time seeing and feeling the connection between community work and their academic work, especially in their first few years. This course is a way to build a clearer bridge.”

The new course grew out of the Curricular Innovations Action Planning Group, which Kristin was also a part of, who recommended that the faculty work to create a link between the governance model and the curriculum. It also builds on a group tutorial taught by math professor Matt Ollis and Helen Pinch ’18, who were part of the same action planning group during the fall of 2017 when Helen was serving as head selectperson.

“In the curricular innovation group, Matt and I had been talking about marrying academics with community governance, and trying to find a common thread that defines a Marlboro experience,” says Helen. “Instead of Plan being just an individualized, isolating experience, we wanted to include within the Marlboro experience this element that is much more expansive— of being an autonomous individual, but in a self-governing community.”

Matt and Helen’s tutorial supported students to go beyond their roles in community governance and do larger projects that were linked to their studies. For example, junior Eric Wefald created a handbook for the position of public advocate, a key community leadership position tied to Community Court. “At Marlboro, I believe we aim to put our democratic values into action,” says Eric.

The first Community and Governance Colloquium was taught by Matt and chemistry professor Todd Smith last spring, and included research and writing projects relating to Title IX, the Real Food Challenge, Town Meeting, and the role of the Town Meeting moderator. Part of the rationale for offering it as a course is that it is more visible to prospective students as well as more accessible to new students who are not yet doing tutorial work.

“I loved having conversations with the others in the class about what we like and what frustrates us regarding Town Meeting and the way Marlboro’s governance works,” says sophomore Phoenix Bieneman, who served as Town Meeting moderator last year. “I learned a lot, and I also found that we were able to talk about possible solutions.”

“I enjoyed the students’ dedication to the spirit of community engagement and self-governance, and it was exciting to see the commitment they had to their projects,” says Todd. “They were all quite committed, both to contributing their voices in campus governance, and to advocating for real change on campus.”

Students in the course apply academic skills to deepen their work on committees and in community roles. Each student crafts their own “work contract” with the faculty running the course so their assignments are shaped around the work they’re doing in the community. The course also includes some communal skill-building, in the form of workshops with guest speakers, shared readings, group projects, or discussions, to address gaps students may experience when diving into community work.

“I am looking forward to the chance to formalize the bridge between my teaching and the things I’ve learned from 12 years of participation in community governance at Marlboro,” says Kristin, who is co-teaching the course this fall with American studies professor Kate Ratcliff. “Working with Kate and a group of students whom I don’t usually see in my classes will be a treat, and it will offer us all a chance to deepen our understanding of our community while helping to strengthen it at the same time.”

Marlboro Partners with Nigerian University

Last spring, four years after they were abducted from a school in Nigeria, more than 100 girls released by Boko Haram were attending the American University of Nigeria (AUN). This is the same university, located in Adamawa State and known for its focus on sustainable development in Africa, that launched a new partnership with Marlboro College in March.

“Marlboro is committed to offering students international experiences that expand their horizons and launch them into a life of meaningful work,” says President Kevin, who serves on the board of directors at AUN and visited Nigeria in March to sign a memorandum of understanding with the university. “We already have partnerships in China, Mexico, Germany, Slovakia, and Czech Republic, as well as with domestic programs, and we are thrilled that our first collaboration in Africa is at AUN.”

President Kevin was introduced to AUN through his longtime colleague Bob Pastor, a fellow Peace Corps Volunteer and a writer and member of the National Security Council. Pastor helped establish AUN, working closely with its founder, Atiku Abubakar, former vice president of Nigeria.

“I worked with Atiku and Bob, in my role as president of the National Peace Corps Association, to launch the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award,” says Kevin, who returned to Nigeria in May to speak at the installation of AUN’s new president, Dawn Dekle, and to meet with Abubakar. “This award recognizes individuals like Atiku, whose lives were influenced by their interactions with Peace Corps Volunteers, leading to a life of service to community and country.”

The specific goals of the cooperative relationship with AUN are to cultivate engaged learning between students and faculty from both institutions through student exchanges. The partnership will also provide for other joint academic endeavors, such as summer programs or faculty exchanges of mutual benefit.

“AUN is an ideal partner for Marlboro, with its focus on arts and sciences, but also technology and entrepreneurship, in the interest of future sustainable development,” says Maggie Patari, Marlboro’s director of global learning and international services. “We are fortunate to have this new partner providing the skills and leadership to help students address the social and economic challenges in the region and the world.”

See the New York Times article about the abducted girls, now young women, attending AUN, including powerful and moving portraits.

Also of Note

“In creating my Plan in religious studies and psychology, I felt it was integral that I grow my understanding of life and the world beyond the classroom and outside of the bubble and great privilege of being a US citizen,” says junior Janelle Kesner (pictured, right). She spent the 2017–18 academic year at the Rothberg International School at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, taking classes in psychology, religion, language, and cross-cultural and political relations. “My studies abroad were broadened by observing, learning, and immersing myself in the many cultures of Israel. Conversing day and night with people helped me to grow a personal understanding, rather than relying on the consensus of the media.”

“In creating my Plan in religious studies and psychology, I felt it was integral that I grow my understanding of life and the world beyond the classroom and outside of the bubble and great privilege of being a US citizen,” says junior Janelle Kesner (pictured, right). She spent the 2017–18 academic year at the Rothberg International School at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, taking classes in psychology, religion, language, and cross-cultural and political relations. “My studies abroad were broadened by observing, learning, and immersing myself in the many cultures of Israel. Conversing day and night with people helped me to grow a personal understanding, rather than relying on the consensus of the media.”

Despite sticky competition from rice noodles, rice-stuffed peppers, rice paper–wrapped spring rolls, and Nigerian jollof rice as mentioned in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, COO Becky Catarelli ’04 won the first annual Rice-Aron Library Cook-Off in May. Rice-inspired dishes prepared by staff were judged based on their use of rice, connection to any book theme, and other criteria such as appearance (from “beautiful food” to “are you sure that’s food?”). Becky gained high marks from the judges for a book-shaped cake decorated to look like Memnoch the Devil, by Anne Rice, and was awarded the coveted golden-rice-encrusted trophy.

In June, sophomore and dancer/choreographer Ricarrdo Valentine performed a new work-in-progress titled Hawa (The Ride) at Abrons Arts Center in New York City, as part of his duo with his partner, Orlando Zane Hunter Jr. “Brother(hood) Dance! is an interdisciplinary duo that seeks to inform its audiences on sociopolitical and environmental injustices from a global perspective, bringing clarity to the same-gender-loving African- American experience in the 21st century.” The culmination of their AIRspace residency, Hawa (The Ride) is a contemporary myth that “takes up black masculinity and the politics of adornment as source material for a creative fashioning of the future self.”

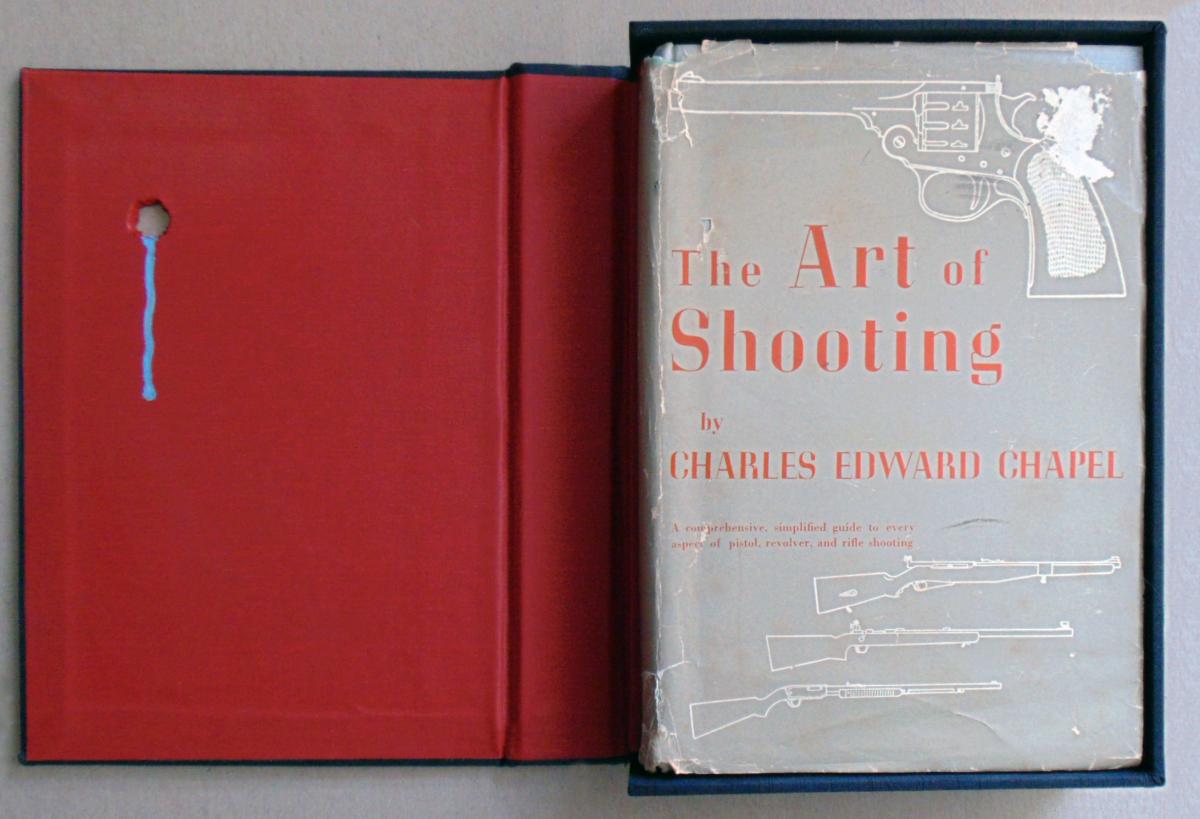

The Art of Shooting: Us & Them, a work by Richard Reitz Smith, communication and design manager, was featured in an exhibition titled “Opulence: Not Everything That Glitters Is Gold,” from July through September at New York’s Center for Book Arts. The work (pictured, right) evolves from a 1950 primer on good sportsmanship to what is now a loaded topic on so many levels. “I believe in beauty, its power, and its poetry,” says Richard. “I see them, even if they are ugly and painful, because I know that there is a story waiting to evolve and we must see and hear that tale.”

The Art of Shooting: Us & Them, a work by Richard Reitz Smith, communication and design manager, was featured in an exhibition titled “Opulence: Not Everything That Glitters Is Gold,” from July through September at New York’s Center for Book Arts. The work (pictured, right) evolves from a 1950 primer on good sportsmanship to what is now a loaded topic on so many levels. “I believe in beauty, its power, and its poetry,” says Richard. “I see them, even if they are ugly and painful, because I know that there is a story waiting to evolve and we must see and hear that tale.”

Through Marlboro’s partnership with the College for Social Innovation, junior Sage Kampitsis spent last spring semester as a Social Innovation Fellow in Boston, working with the Steppingstone Foundation, a nonprofit organization bridging the opportunity gap in education. She tutored middle school students, and conducted a research study on the effectiveness of the program’s admission process. “My ‘Semester in the City’ not only tied into my coursework at Marlboro, but shaped it as well,” says Sage. “It was through this program that I discovered my passion for empowerment education and decided to focus my Plan work around that passion.” See Sage share her own empowerment journey.

“I see Marlboro as a place of tremendous opportunity, both for our students who want to engage in the serious pursuit of a unique education, and for our supporters who can help to make that happen,” says Rennie Washburn, director of advancement, who joined the college in January. Rennie comes to Marlboro with 17 years of experience in many different facets of development work, most recently at Northfield Mount Hermon, where she was the director of alumni and parent giving programs. She recently guided Annual Fund giving to a record $2.2 million last fiscal year, which ended June 30.

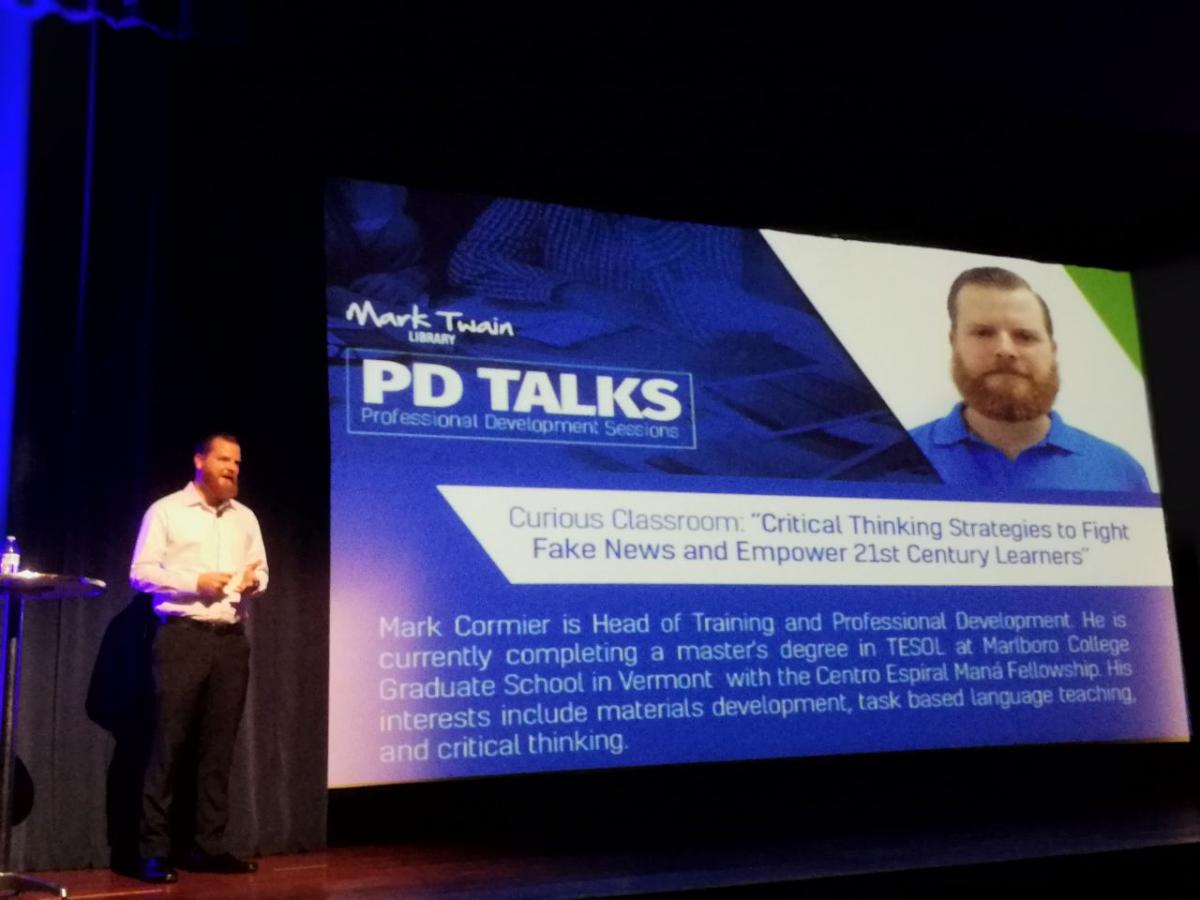

In April, MATESOL student Mark Cormier (pictured, right) gave a presentation for PD Talks, a public speaker series open to teachers and education students, hosted by the Mark Twain Library in San Jose, Costa Rica. “I talked about fake news and common cognitive biases and logical fallacies that contribute to its prevalence and impact, as well as the importance of harnessing our students’ natural curiosity as a tool for developing a more critical eye,” says Mark. He is head of training and professional development at the Centro Cultural Costarricense Norteamericano, a nonprofit English school and cultural center in San Jose promoting exchange between Costa Rica and the U.S.

In April, MATESOL student Mark Cormier (pictured, right) gave a presentation for PD Talks, a public speaker series open to teachers and education students, hosted by the Mark Twain Library in San Jose, Costa Rica. “I talked about fake news and common cognitive biases and logical fallacies that contribute to its prevalence and impact, as well as the importance of harnessing our students’ natural curiosity as a tool for developing a more critical eye,” says Mark. He is head of training and professional development at the Centro Cultural Costarricense Norteamericano, a nonprofit English school and cultural center in San Jose promoting exchange between Costa Rica and the U.S.

Junior Karla Julia Ramos and sophomore Annalise Guidry travelled with theater professor Jean O’Hara to Scotland in August for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the largest arts festival in the world. They were there to represent Marlboro College and to share their original performance, 3 Women, 3 Myths, a journey of exploration into how each of us is informed by our ancestors: their music, their languages, their spiritual practices, and their stories. With roots in Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Ireland, respectively, each of the performers explored how their ancestors were brought across the ocean, and worked with the theme of water to tie in ancient myths from their families.

Marlboro was pleased to welcome Fumio Sugihara as the new director of admissions in August. Fumio comes to Marlboro from Bennington College, where he was director of admissions, but he has also worked in admissions at University of Puget Sound and Juniata College. He started his career in higher education at Bowdoin College, where he was director for multicultural recruitment and associate director of admissions. Fumio earned a bachelor’s degree at Bowdoin in women’s studies and environmental studies, and went on to earn a master’s degree in higher education from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

Minds on Main Street  Three finalists in the Beautiful Minds Challenge explore Brattleboro, part of the symposium in April that welcomed more than 20 innovative high school students from all over the US as well as Kazakhstan, Jordan, and Ecuador. Learn about this year’s contest at minds.marlboro.edu. Photo by Kelly Fletcher

Three finalists in the Beautiful Minds Challenge explore Brattleboro, part of the symposium in April that welcomed more than 20 innovative high school students from all over the US as well as Kazakhstan, Jordan, and Ecuador. Learn about this year’s contest at minds.marlboro.edu. Photo by Kelly Fletcher

Spring Bounty Freshman Faza “Jimmy” Hikmatullah discovers a wealth of wood frog eggs in a vernal pool, part of biology professor Jaime Tanner’s Life in the Cold class. An international student from Indonesia, Jimmy embraced his first real winter with gusto. Photo by Cedar van Tassel ’21

Parlez Vous  Lucy Johnston ’21, Margaret Brooks ’21, and Brooke Evans ’19 were among a group of six students who traveled to France in May with French language and literature fellow Frédérique Marty. They hiked in the Pyrenees, met with students in Bayonne, and learned about the history of chocolate in Basque country. Photo by Charlotte Nicholson ’18

Lucy Johnston ’21, Margaret Brooks ’21, and Brooke Evans ’19 were among a group of six students who traveled to France in May with French language and literature fellow Frédérique Marty. They hiked in the Pyrenees, met with students in Bayonne, and learned about the history of chocolate in Basque country. Photo by Charlotte Nicholson ’18

Making Change In February, Director of Experiential Learning and Career Development Kate Trzaskos (left) and others on campus welcomed representatives from Ashoka U, part of the process of becoming an Ashoka Changemaker Campus. Photo by Travis Hellstrom

Student Art

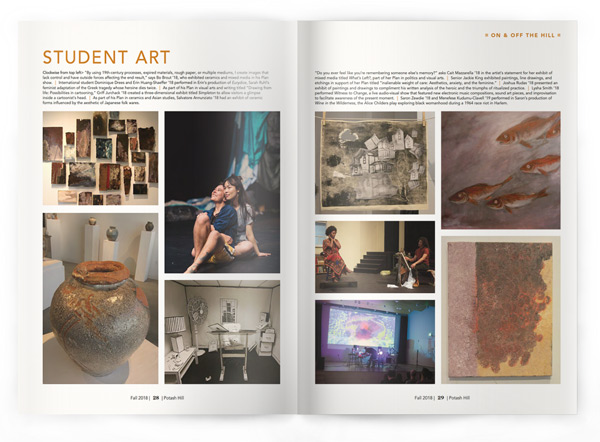

First page, clockwise from top left> “By using 19th-century processes, expired materials, rough paper, or multiple mediums, I create images that lack control and have outside forces affecting the end result,” says Bo Brout ’18, who exhibited ceramics and mixed media in his Plan show. | International student Dominique Drees and Erin Huang-Shaeffer ’18 performed in Erin’s production of Eurydice, Sarah Ruhl’s feminist adaptation of the Greek tragedy whose heroine dies twice. | As part of his Plan in visual arts and writing titled “Drawing from life: Possibilities in cartooning,” Griff Jurchack ’18 created a three-dimensional exhibit titled Simpleton to allow visitors a glimpse inside a cartoonist’s head. | As part of his Plan in ceramics and Asian studies, Salvatore Annunziato ’18 had an exhibit of ceramic forms influenced by the aesthetic of Japanese folk wares.

Second page, clockwise from top left> “Do you ever feel like you’re remembering someone else’s memory?” asks Cait Mazzarella ’18 in the artist’s statement for her exhibit of mixed media titled What’s Left?, part of her Plan in politics and visual arts. | Senior Jackie King exhibited paintings, line drawings, and etchings in support of her Plan titled “Inalienable weight of care: Aesthetics, anxiety, and the feminine.” | Joshua Rudas ’18 presented an exhibit of paintings and drawings to compliment his written analysis of the heroic and the triumphs of ritualized practice. | Lysha Smith ’18 performed Witness to Change, a live audio-visual show that featured new electronic music compositions, sound art pieces, and improvisation to facilitate awareness of the present moment. | Saron Zewdie ’18 and Menefese Kudumu-Clavell ’19 performed in Saron’s production of Wine in the Wilderness, the Alice Childers play exploring black womanhood during a 1964 race riot in Harlem.

Events

1 Music professor Matan Rubinstein was joined by two master musicians, Wes Brown on double bass and Royal Hartigan on drums and percussion, for a concert of original works in February. 2 In April, the Samara Piano Quartet made an appearance at Marlboro College as one of their inaugural season of concerts, part of the Music for a Sunday Afternoon series. 3 The spring featured two gender-free contra dances, welcoming members from the local community and featuring music performed by Clayton Clemetson ’19 and Willy Clemetson ’21. 4 This year’s Wendell-Judd Cup cross-country ski and snowshoeing event in February featured a new starting point, on the soccer field, as well as sporty new caffeinated bibs. 5 In May, students and faculty performed a reading of the play Salmon Is Everything, a community response to fish mortality on the Klamath River, followed by a discussion led by Shaunna Oteka McCovey, member of the Yurok Nation. 6 Lynn Mahoney Rowan ’09 and Will Thomas Rowan ’08 returned in February with their quartet Windborne to sing from their Song of the Times album, featuring songs for peoples’ rights from the past 400 years. 7 A February screening of Possible Algeria, which recounts the life journey of Algerian anti-colonial activist Yves Mathieu, was followed by a discussion with Dartmouth professor Jeffrey Ruoff and filmmaker Viviane Candas, Mathieu’s daughter.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

In May, Hannah Noblewolf ’18 sat down with math professor Matt Ollis to talk about math— obviously—as well as game theory, student research, and sustainability. You can read the whole interview.

HANNAH: What about math appeals to you so much?

MATT: It’s fun to work on, very similar in vibe to solving puzzles. Like, if you enjoying doing Sudoku puzzles, it’s the same sort of feeling of not knowing how to do something, figuring out how to work it all out, putting it all together, and a feeling of success when you do it.

H: Do you think everyone should do math to some extent?

M: Sort of, but only in the way that I think everyone should do languages, and poetry, and like a hundred other things that no one actually has the time to do all of. I’m certainly against having a math requirement at Marlboro. I really like the sort of structure where people work out what it is they want to do and need to do, and are able to do that.

H: What would you say is your favorite thing about teaching at Marlboro?