Spring 2019

Editor's Note

“Climate change is . . . both a moral challenge and a challenge to moral theory,” says philosophy professor William Edelglass in his feature titled “Life in the Anthropocene.” “We find ourselves caught in a situation where together we cause immense suffering and our inherited moral theory has difficulty conceptualizing any moral responsibility.”

“Climate change is . . . both a moral challenge and a challenge to moral theory,” says philosophy professor William Edelglass in his feature titled “Life in the Anthropocene.” “We find ourselves caught in a situation where together we cause immense suffering and our inherited moral theory has difficulty conceptualizing any moral responsibility.”

This new epoch of spreading deserts, shrinking ice caps, rising oceans, and growing legions of refugees poses many challenges for humans, ethically but also legislatively, scientifically, culturally, and in our practical day-to-day lives. In her feature titled “Going Through the Narrows,” MA in Teaching for Social Justice student Judy Dow shares lessons of her ancestors that call for adapting to change, something Native communities of the continent have good reason to know about.

Adapting is something Marlboro College knows about as well. In a time when small liberal arts colleges in the region are all facing significant enrollment and financial challenges, Marlboro has the optimism and agility to reimagine our curriculum and reinforce our promise to students in response to changing times. The college has also been able to leverage their longtime partnership with the Marlboro Music School and Festival for sustaining support and two new buildings.

Marlboro has long prepared students for a changing world, and the entrepreneurial activities of our alumni are a testament to this adaptability. Whether it’s arts entrepreneurs like Laura Frank ’92, Samuel Dowe-Sandes ’96, and Evan Lorenzen ’13, or justice-based bookkeeper Alex Fischer MBA ’14, alumni consistently credit Marlboro with preparing them for the entrepreneurial life. How did Marlboro prepare you for life in the Anthropocene?

How are you responding to the challenges of a changing world? If you have any insights or reactions to this issue of Potash Hill, I hope you’ll share them with me at pjohansson@marlboro.edu. —Philip Johansson, editor

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Alumni Director: Maia Segura ’91

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Richard Smith

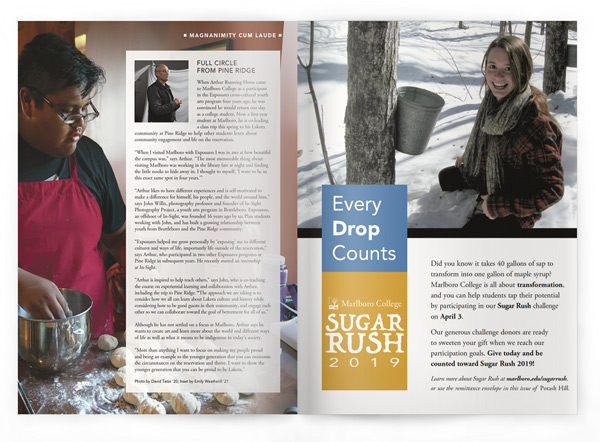

Staff Photographers: Clayton Clemetson ’19, David Teter ’20, and Emily Weatherill ’21

Design: Falyn Arakelian

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: A basket woven from hand-pounded ash by Judy Dow, a teacher of traditional Abenaki culture and student in Marlboro’s MA in Teaching for Social Justice program, demonstrates traditional “cowass” designs: turns and curls representing birds, snails, and porcupine quills. “Wabanaki people have always made ash baskets,” says Judy. “However, this style is called a fancy basket, and was an adaptation during the late 1800s.” Judy shares lessons for adapting to impending environmental, social, and economic changes in her article, "Going Through the Narrows."

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

“Our job is to make sure that every international student at Marlboro has the best possible experience that they can get, and we can’t wait to welcome you here,” say Dora Musini, international services coordinator, and Emma Huse, experiential learning and global engagement coordinator. They were featured in a video produced by students as part of the national #YouAreWelcomeHere campaign, which offers welcoming messages to international students around the world. See the video.

“Our job is to make sure that every international student at Marlboro has the best possible experience that they can get, and we can’t wait to welcome you here,” say Dora Musini, international services coordinator, and Emma Huse, experiential learning and global engagement coordinator. They were featured in a video produced by students as part of the national #YouAreWelcomeHere campaign, which offers welcoming messages to international students around the world. See the video.

Up Front

Merengue in Marlboro

“Why do we social dance, and in what ways does the social dancing space exist and become created? Who/what creates it? Why is social dance important? I am interested in the ways bodies interact on and off the dance floor, and the ways we communicate verbally and with our bodies. I will always seek to understand the sensation of letting go that is created by giving into the music and dance.”

— Karissa Wolivar ’18

Karissa presented an interactive Plan show in November titled “Textura/Texture.” Karissa choreographed performances of five forms of Latin social dance she experienced in her study abroad experience in Costa Rica—merengue, bachata, bolero, salsa, and cumbia—and invited audience members to participate.

Photo by Clayton Clemetson ’19

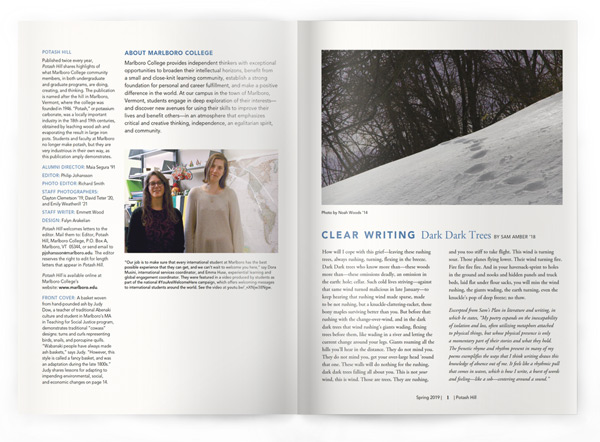

Clear Writing

Dark Dark Trees

By Sam Amber '18

How will I cope with this grief—leaving these rushing trees, always rushing, turning, flexing in the breeze. Dark Dark trees who know more than—these woods more than—these omissions deadly, an omission in the earth: hole; cellar. Such cold lives striving—against that same wind turned malicious in late January—to keep hearing that rushing wind made sparse, made to be not rushing, but a knuckle-clattering-racket, those bony maples surviving better than you. But before that: rushing with the change-over-wind, and in the dark dark trees that wind rushing’s giants wading, flexing trees before them, like wading in a river and letting the current change around your legs. Giants roaming all the hills you’ll hear in the distance. They do not mind you. They do not mind you, get your over-large head ’round that one. These walls will do nothing for the rushing, dark dark trees falling all about you. This is not your wind, this is wind. Those are trees. They are rushing, and you too stiff to take flight. This wind is turning sour. Those planes flying lower. Their wind turning fire. Fire fire fire fire. And in your haversack-sprint to holes in the ground and nooks and hidden panels and truck beds, laid flat under flour sacks, you will miss the wind rushing, the giants wading, the earth turning, even the knuckle’s pop of deep freeze; no thaw.

Excerpted from Sam’s Plan in literature and writing, in which he states, “My poetry expands on the inescapability of isolation and loss, often utilizing metaphors attached to physical things, but whose physical presence is only a momentary part of their stories and what they hold. The frenetic rhyme and rhythm present in many of my poems exemplifies the ways that I think writing draws this knowledge of absence out of me. It feels like a rhythmic pull that comes in waves, which is how I write, a burst of words and feeling—like a sob—centering around a sound.”

Photo by Noah Woods ’14

Letters

Clear Writing

Clear Writing

In “Anti-Essentialism in Black Thought” (Fall 2018), Andrew Smith Domzal ’18 identifies and clearly expresses what he is going to write about. Somewhere (Marlboro?) he has learned to write a good sentence; to write a good sentence is the beginning of thinking clearly. I like the tone and measure of his prose. I look forward to reading his Plan.

I enjoyed my two-day visit to Marlboro in the mid 1980s, when my son Stephen was a prospective student. I attended two classes, wandered the lovely, rustic campus on muddy paths, and spoke to students and staff, occasionally catching sight of Stephen, who stayed clear of me. I stayed on campus in a ramshackle building that also housed a day school for little children. I ate, with everyone, in the former barn that also served as auditorium and theater. It was a wonderful stay.

—Charles Perrone P’89

Book Shelf

Thanks for the coverage of my book All That Once Was You in Potash Hill (Fall 2018). Just got my copy. BTW, it’s really an improvement! Gorgeous magazine.

—Thomas Griffin ’86

Remembering Markus Markus Brakhan ’86 (pictured left with me), who passed away last summer (Potash Hill, Fall 2018), was a bright and vibrant part of the Marlboro community from 1982 to 1986 and wrote his Plan of Concentration on Kant and the “virtuous man.” He was a true original, whose soul deeply touched and impacted those close to him.

Markus Brakhan ’86 (pictured left with me), who passed away last summer (Potash Hill, Fall 2018), was a bright and vibrant part of the Marlboro community from 1982 to 1986 and wrote his Plan of Concentration on Kant and the “virtuous man.” He was a true original, whose soul deeply touched and impacted those close to him.

—Kip Morgan ’86

Marlboro Love

I am thankful daily for my time spent at Marlboro. I had the freedom to explore and define questions and commitments that have lasted for decades; I had a community that held me accountable, intellectually and personally. I began to learn what it means to be a thoughtful citizen. Thanks, Marlboro! Onward together.

—Mark Genszler ’95

Marlboro is a magical place. As I experienced it, every individual was honored for being the unique person they are. They were coaxed into doing their best and growing so much, so positively, throughout. This environment creates a community where you can and want to make a difference.

—Christina Crosby ’89

Policy in Action For a politics student, Marlboro is like an enormous playground, where you can test things out—Meg Mott in particular is a professor who encourages you to take what you’re learning in the classroom and test it out on her colleagues, which is funny. She was really good at encouraging us to take theories and then formulate a policy change, go to the appropriate committee, and persuade those people that it was the right policy.

For a politics student, Marlboro is like an enormous playground, where you can test things out—Meg Mott in particular is a professor who encourages you to take what you’re learning in the classroom and test it out on her colleagues, which is funny. She was really good at encouraging us to take theories and then formulate a policy change, go to the appropriate committee, and persuade those people that it was the right policy.

And I think that for me those skills were invaluable: being able to go into a room and speak to whoever was on that committee, and being able to handle that there is a time limit on what you have to say and that you have to consider what everyone thinks. There is someone in the room who vehemently disagrees with you, and you’re going to have to persuade them because you all live on campus together. That’s a really good microcosm of what my day-to-day office life is like.

— Alexia Boggs ’13, aerospace lawyer

Excerpted from the young alumni panel at Home Days 2018. See the whole panel.

Photo of Alexia and Sean Pyles ’13, also part of the alumni panel, by Kelly Fletcher

View from the Hill

Reimagining Marlboro

By Kevin F. F. Quigley

There is a well-known Chinese expression, “may you live in interesting times.” For Marlboro, and many other small colleges, these are indeed interesting times full of challenges. Marlboro, for not the first time in its history, is confronting a set of enrollment and financial challenges. At its May 2018 meeting, the board of trustees agreed to a multipronged “Reimagining Marlboro” project to address these challenges.

In June, a faculty task force was set up to “reimagine the curriculum” (see page 18). A dedicated group of nine faculty members worked assiduously over the summer to meet a September deadline. Working closely with a group of consultants, these faculty members examined marketing and assessment data and considered what was the essence of a Marlboro education and whether we had a distinctive niche that would attract future students. Together, the faculty developed the “Marlboro Promise.” Under this promise, every student at Marlboro, while pursuing their academic passion, will learn three things: (1) write clearly, (2) live in a community, and (3) lead a big idea from conception to execution. These three elements of the promise are reflected in what we already do: writing portfolio, community governance, and Plan.

The promise provides a clearer way to communicate to prospective students and their families what every student learns at Marlboro, as well as offering a “contract” related to that learning. The promise also helps our students clearly describe what it is they learned at Marlboro and how that applies to securing meaningful work. The Marlboro Promise was approved at a special meeting of the board on September 22.

Alongside this faculty work, we also set out to reimagine our admissions work and strengthen support for student success. In August, we welcomed Fumio Sugihara as dean of admissions and financial aid. Previously director of admissions at Bennington, Fumio brings a breadth of experience at liberal arts colleges and a data-driven, innovative approach to the challenging work of admissions. He has already begun to incorporate the Marlboro Promise in communications to prospective students. Working with consultants, Marlboro is also developing a new website built around the promise, due to be launched later this spring.

It has been said that challenges are what makes life interesting; overcoming them is what makes life meaningful. Marlboro is always an interesting place and throughout its history has frequently encountered and overcome challenges. I am confident that working together we will address these challenges in ways that add great meaning to the uniqueness of Marlboro.

Photo by Kelly Fletcher

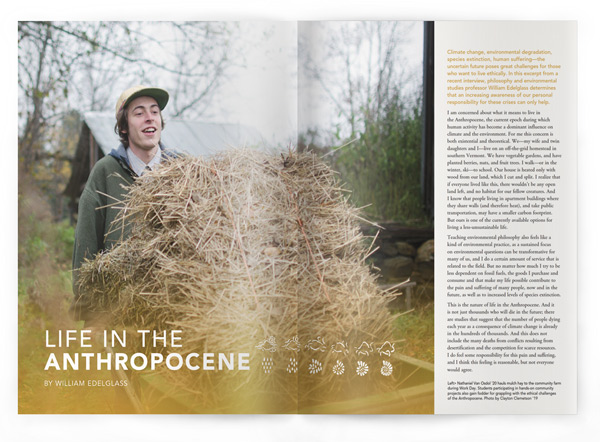

Life in the Anthropocene

By William Edelglass

Climate change, environmental degradation, species extinction, human suffering—the uncertain future poses great challenges for those who want to live ethically. In this excerpt from a recent interview, philosophy and environmental studies professor William Edelglass determines that an increasing awareness of our personal responsibility for these crises can only help.

I am concerned about what it means to live in the Anthropocene, the current epoch during which human activity has become a dominant influence on climate and the environment. For me this concern is both existential and theoretical. We—my wife and twin daughters and I—live on an off-the-grid homestead in southern Vermont. We have vegetable gardens, and have planted berries, nuts, and fruit trees. I walk—or in the winter, ski—to school. Our house is heated only with wood from our land, which I cut and split. I realize that if everyone lived like this, there wouldn’t be any open land left, and no habitat for our fellow creatures. And I know that people living in apartment buildings where they share walls (and therefore heat), and take public transportation, may have a smaller carbon footprint. But ours is one of the currently available options for living a less-unsustainable life.

Teaching environmental philosophy also feels like a kind of environmental practice, as a sustained focus on environmental questions can be transformative for many of us, and I do a certain amount of service that is related to the field. But no matter how much I try to be less dependent on fossil fuels, the goods I purchase and consume and that make my life possible contribute to the pain and suffering of many people, now and in the future, as well as to increased levels of species extinction.

This is the nature of life in the Anthropocene. And it is not just thousands who will die in the future; there are studies that suggest that the number of people dying each year as a consequence of climate change is already in the hundreds of thousands. And this does not include the many deaths from conflicts resulting from desertification and the competition for scarce resources. I do feel some responsibility for this pain and suffering, and I think this feeling is reasonable, but not everyone would agree.

Instead of thinking about individual responsibility, one might object, we need to think about climate change as a tragedy of the commons. Instead of holding individuals responsible, then, we should work toward forging agreements that would regulate the commons that is our atmosphere. According to the tragedy of the commons view of climate change, there would be no unilateral obligation to reduce one’s own greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change and other common-pool resource problems, then, would constitute a kind of prisoners’ dilemma, in which individuals acting according to their preferences worsen the situation for everyone. What would be required, then, is an enforceable, collective agreement.

Or, one might object, while it may be the case that cumulatively our actions are catastrophic, no one individual actually causes climate change. This is sometimes called the problem of inconsequentialism: if the consequences of my actions are negligible, and there would be no discernible difference if I drove a low- or high-mileage car, then I am simply not responsible. If my individual choice of a low-mileage car doesn’t really cause climate change, then there is nothing morally wrong with it. According to this view, the only moral obligation we have is to support systemic changes at a policy level by electing and supporting politicians who will implement incentives and regulations that will make a consequential difference.

Or, one might object, while it may be the case that cumulatively our actions are catastrophic, no one individual actually causes climate change. This is sometimes called the problem of inconsequentialism: if the consequences of my actions are negligible, and there would be no discernible difference if I drove a low- or high-mileage car, then I am simply not responsible. If my individual choice of a low-mileage car doesn’t really cause climate change, then there is nothing morally wrong with it. According to this view, the only moral obligation we have is to support systemic changes at a policy level by electing and supporting politicians who will implement incentives and regulations that will make a consequential difference.

Clearly, regulation, legislation, and international political agreements are necessary to make significant progress in mitigating and adapting to climate change. Moreover, it can be problematic to hold someone morally responsible for choices that are limited by their economic and social context, in which it may be very hard to make decisions that result in fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

There are also theoretical obstacles to understanding individual moral responsibility in the context of climate change. As Dale Jamieson, a philosopher at NYU, has argued, climate change and other collective-action environmental problems pose a challenge to our traditional conceptions of moral responsibility. Because individually my actions are inconsequential, I intend no harm, and there is no immediate victim, according to the standard account of responsibility I am not responsible for the suffering that results from climate change.

Climate change is thus both a moral challenge and a challenge to moral theory because we find ourselves caught in a situation where together we cause immense suffering and our inherited moral theory has difficulty conceptualizing any moral responsibility. But there are vast numbers of people today who do feel morally responsible. And I think there are ways of conceptualizing moral responsibility that make sense of that feeling. One way is by drawing on the work of Emmanuel Levinas (1906–95), the Lithuanian-French phenomenologist whose account of responsibility turns the standard approach on its head.

In Levinas’s moral phenomenology, responsibility is not grounded in intention and causality. According to most moral philosophies, and our common intuitions, we are responsible for acts that we choose, especially when we understand the consequences of our choices. Likewise, causal responsibility is generally understood to be a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for moral responsibility.

In Levinas’s moral phenomenology, responsibility is not grounded in intention and causality. According to most moral philosophies, and our common intuitions, we are responsible for acts that we choose, especially when we understand the consequences of our choices. Likewise, causal responsibility is generally understood to be a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for moral responsibility.

Thus, we generally tend to recognize moral responsibility for acts that are close in space and time, where we see clear connections between perpetrators and victims. In the standard account, because ought implies can, responsibility does not demand more than is reasonably possible for the agent. However, for Levinas, ethical consciousness is precisely the sense of responsibility for the Other, even when I myself have done nothing to harm her. And the more attentive I am the more I recognize my own responsibility.

In a brief autobiographical sketch titled “Signature,” Levinas writes that his life and work were “dominated by the presentiment and the memory of the Nazi horror.” Levinas himself entered the French military and was captured shortly after the start of the Second World War. He spent the next four years in a labor camp in Germany, hearing rumors of the murder of European Jews. His parents, grandparents, both his brothers, and many others close to him were killed by the Nazis; Levinas’s wife and daughter spent the war years hiding in France. For Levinas, the Nazi horror and the goodness of some when confronted by overwhelming force, demanded a radical rethinking of ethics, which became the central philosophical project of his life. It is primarily a project of rethinking our relationship to the other person, which, as he notes, also demands a rethinking of subjectivity.

In contrast to most Western moral philosophies, Levinas’s ethics offers no universal moral principles or prescriptions. He does not seek to answer the questions that animate these traditions, such as: “what is the best human life?”; “how should I live?”; “how ought one to act?”; or “what principles of moral reason can determine what one ought to do?” Instead, Levinas describes the very moral consciousness that precedes and motivates all moral thinking and action. In part due to this approach, then, Levinas’s thought is not in tension with virtue ethics, deontology, consequentialism, or other moral theories; it is operating at a prior level.

Levinas’s phenomenology describes a normative force to respond to the Other, to engage in the world, but there is no particular rule to follow or virtue to cultivate that would be universally applicable. For Levinas, then, there is no escape from the moral dilemmas of social life, for we are incessantly called by a responsibility to address needs that always demand more than the capacities and resources we possess. This will sound familiar to anyone who considers the global crisis of climate change their moral responsibility.

Levinas’s phenomenology describes a normative force to respond to the Other, to engage in the world, but there is no particular rule to follow or virtue to cultivate that would be universally applicable. For Levinas, then, there is no escape from the moral dilemmas of social life, for we are incessantly called by a responsibility to address needs that always demand more than the capacities and resources we possess. This will sound familiar to anyone who considers the global crisis of climate change their moral responsibility.

Levinas’s ethics of difference and singularity has been quite influential, provoking increased attention to ethical aspects of social life in a variety of fields in the humanities and social sciences. His work is not, however, generally regarded as an intellectual resource for thinking about environmental issues. But I believe Levinas does have something to offer us in this new era of global crises.

A generation ago, many environmental philosophers and activists tended to ground their work in one form or another of non-anthropocentrism. These views recognized an intrinsic value in nature that made it important to consider nature as a subject of our ethics. The idea that “nature,” as some abstract, ahistorical other to humans and human culture, could be a source of moral obligation is alien to Levinas’s thought. For Levinas, “nature” is precisely that realm which is outside the purview of ethics; it is distinguished instead by its drive to persist and its inability to put the Other before the self as humans are able.

Today, though, many environmental thinkers and activists articulate their concerns using conceptual frameworks that are less reliant on non-anthropocentric metaphysical and ethical views. Indeed, the climate movement, including the intellectual work that motivates it, is now very much a climate justice movement. Levinas’s recurrent concern with “the precariousness of the Other” resonates with this contemporary emphasis on climate justice, with a concern for the ways in which resource depletion and pollution overload harm humans as well as other animals.

The ethical challenges of the Anthropocene call for new approaches and fresh looks at old ones. Levinas’s account of responsibility works well for understanding our moral situation in collective-action environmental challenges such as climate change. More generally, I find Levinas’s phenomenology provides an apt description of ethical life in the Anthropocene: I have inescapable responsibilities that increase with my awareness and are always beyond my capacities to meet. That will not keep me from trying, and learning, and teaching my way into this new epoch.

William Edelglass is professor of philosophy and environmental studies, and co-editor of Facing Nature: Levinas and Environmental Thought (Duquesne University Press, 2012). He co-edits the journal Environmental Philosophy and has served as co-director of the International Association of Environmental Philosophy (IAEP), where he is currently chair of the board of directors. This article is excerpted and adapted from an interview William did on 3:AM.

Unintended Consequences of Growth “I found it unbelievable that we rely so heavily on a number presumed to be infinite, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while we count the extraction of finite resources in its measurement of growth,” says Spencer Knickerbocker ’19, who is completing his Plan in economics. “I also struggled with the fact that the number in no way captures the cost of environmental degradation.” Spencer’s Plan explores the history of GDP, with an emphasis on how using this instrument pushes policy with unintended consequences. He also investigates two alternative instruments to measure societal well-being, and creates his own index that measures elements of economic performance, environmental degradation, and inequality. “I have a growing interest in, and concern for, our future with regards to climate change and resource extraction. It is time for new standards.”

“I found it unbelievable that we rely so heavily on a number presumed to be infinite, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while we count the extraction of finite resources in its measurement of growth,” says Spencer Knickerbocker ’19, who is completing his Plan in economics. “I also struggled with the fact that the number in no way captures the cost of environmental degradation.” Spencer’s Plan explores the history of GDP, with an emphasis on how using this instrument pushes policy with unintended consequences. He also investigates two alternative instruments to measure societal well-being, and creates his own index that measures elements of economic performance, environmental degradation, and inequality. “I have a growing interest in, and concern for, our future with regards to climate change and resource extraction. It is time for new standards.”

Going Through the Narrows

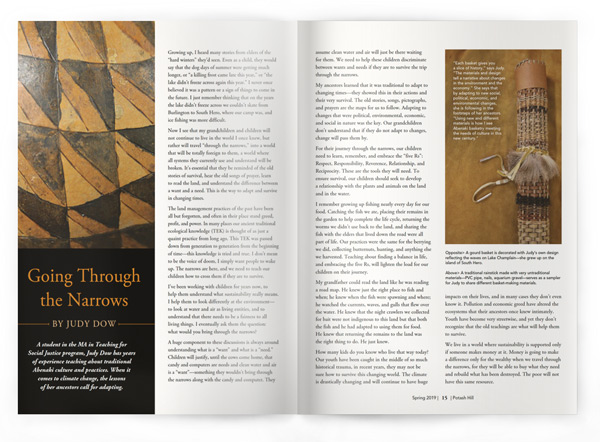

By Judy Dow

A student in the MA in Teaching for Social Justice program, Judy Dow has years of experience teaching about traditional Abenaki culture and practices. When it comes to climate change, the lessons of her ancestors call for adapting.

Growing up, I heard many stories from elders of the “hard winters” they’d seen. Even as a child, they would say that the dog days of summer were getting much longer, or “a killing frost came late this year,” or “the lake didn’t freeze across again this year.” I never once believed it was a pattern or a sign of things to come in the future. I just remember thinking that on the years the lake didn’t freeze across we couldn’t skate from Burlington to South Hero, where our camp was, and ice fishing was more difficult.

Now I see that my grandchildren and children will not continue to live in the world I once knew, but rather will travel “through the narrows,” into a world that will be totally foreign to them, a world where all systems they currently use and understand will be broken. It’s essential that they be reminded of the old stories of survival, hear the old songs of prayer, learn to read the land, and understand the difference between a want and a need. This is the way to adapt and survive in changing times.

The land management practices of the past have been all but forgotten, and often in their place stand greed, profit, and power. In many places our ancient traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is thought of as just a quaint practice from long ago. This TEK was passed down from generation to generation from the beginning of time—this knowledge is tried and true. I don’t mean to be the voice of doom, I simply want people to wake up. The narrows are here, and we need to teach our children how to cross them if they are to survive.

I’ve been working with children for years now, to help them understand what sustainability really means. I help them to look differently at the environment— to look at water and air as living entities, and to understand that there needs to be a fairness to all living things. I eventually ask them the question: what would you bring through the narrows?

A huge component to these discussions is always around understanding what is a “want” and what is a “need.” Children will justify, until the cows come home, that candy and computers are needs and clean water and air is a “want”—something they wouldn’t bring through the narrows along with the candy and computer. They assume clean water and air will just be there waiting for them. We need to help these children discriminate between wants and needs if they are to survive the trip through the narrows.

My ancestors learned that it was traditional to adapt to changing times—they showed this in their actions and their very survival. The old stories, songs, pictographs, and prayers are the maps for us to follow. Adapting to changes that were political, environmental, economic, and social in nature was the key. Our grandchildren don’t understand that if they do not adapt to changes, change will pass them by.

For their journey through the narrows, our children need to learn, remember, and embrace the “five Rs”: Respect, Responsibility, Reverence, Relationship, and Reciprocity. These are the tools they will need. To ensure survival, our children should seek to develop a relationship with the plants and animals on the land and in the water.

I remember growing up fishing nearly every day for our food. Catching the fish we ate, placing their remains in the garden to help complete the life cycle, returning the worms we didn’t use back to the land, and sharing the fish with the elders that lived down the road were all part of life. Our practices were the same for the berrying we did, collecting butternuts, hunting, and anything else we harvested. Teaching about finding a balance in life, and embracing the five Rs, will lighten the load for our children on their journey.

My grandfather could read the land like he was reading a road map. He knew just the right place to fish and when; he knew when the fish were spawning and where; he watched the currents, waves, and gulls that flew over the water. He knew that the night crawlers we collected for bait were not indigenous to this land but that both the fish and he had adapted to using them for food. He knew that returning the remains to the land was the right thing to do. He just knew.

How many kids do you know who live that way today? Our youth have been caught in the middle of so much historical trauma, in recent years, they may not be sure how to survive this changing world. The climate is drastically changing and will continue to have huge impacts on their lives, and in many cases they don’t even know it. Pollution and economic greed have altered the ecosystems that their ancestors once knew intimately. Youth have become very streetwise, and yet they don’t recognize that the old teachings are what will help them to survive.

We live in a world where sustainability is supported only if someone makes money at it. Money is going to make a difference only for the wealthy when we travel through the narrows, for they will be able to buy what they need and rebuild what has been destroyed. The poor will not have this same resource.

Catastrophic storms are beating our shores, washing away the world we know. Towns are being deemed unlivable, sometimes for months and years, and some are being lost forever. Sustainability is understanding that we are responsible for our actions and then doing something about it; all the money in the world won’t fix the environmental problems we have today. It’s time to wake up for our children—allowing them to grow up is our responsibility and the right thing to do.

Loss of life and property is only half the story. We are looking at a rate of evolution in our natural world that we’ve not seen in our lifetimes. Polar bears and grizzly bears are mating; so are different species of everything from butterflies to sharks. The scientific community has recognized this genetic mixing in owls, squirrels, big cats, and wild canines. Is this hybridization natural? Some species-extinction experts say that wiping out hybrids is the best way to protect a threatened species. The lawmakers and wildlife managers will decide what will happen to these hybrid beings, while the people that depend on the land for survival will be dismissed as quaint Indian people who can’t keep up with the times.

The Abenaki have no word for time: when everyone is together and everything is ready, and only then, is it “time.” We understand that we live in a world with limited amounts of birds, fish, animals, and plants, and we’ve grown up understanding the sun rises every morning and sets every night at a predicted time. We’ve learned to read the seasons and the land, and to live with these and the many other predictable natural events we experience day to day.

Many of us have become at peace with the world we live in, assuming this is the way it will always be. Many of us have grown up never getting intimately involved in the world around us unless we are directly affected. While we’ve ignored the bigger picture, our world has changed; we are beginning the passage from the world we now know, through the narrows and into a new world. A different world than we could ever imagine. Life will be difficult, at best, for some, and unbearable for others— and costly in many ways for everyone. The “time” is right to embrace the five Rs and accept adaptation before it is too late.

Judy is a nationally known activist, basket maker, and teacher of traditional Abenaki culture and practices. She is the author of “Understanding the Vermont Eugenics Survey and Its Impacts Today,” in Global Indigenous Health, edited by Robert Henry et al., University of Arizona Press (2018), as well as many other essays. The MA in Teaching for Social Justice program is a collaboration between Marlboro College and Spark Teacher Education Institute: marlboro.edu/spark.

Finding Cultural Connection to the Land “The struggle to protect landscapes from exploitation is simultaneously an effort to preserve the cultures whose understanding of the world is deeply imbedded within those landscapes,” says Chris Lamb ’18. As part of his Plan in philosophy, environmental studies, and literature, Chris had a life-changing internship experience with the Black Mesa Water Coalition, a Diné environmental justice group based in Flagstaff, Arizona. He drew upon this experience to demonstrate the ceremonial and spiritual implications of food sovereignty—and by extension Indigenous activism— as demonstrated by the restoration of traditional corn fields. “Though places and landscapes play a fundamental role in the fabric of all cultures, Diné people have chosen to actively participate in the interplay between human and nonhuman forces in a way that illuminates the power of place and gives agency to the more-than-human world.”

“The struggle to protect landscapes from exploitation is simultaneously an effort to preserve the cultures whose understanding of the world is deeply imbedded within those landscapes,” says Chris Lamb ’18. As part of his Plan in philosophy, environmental studies, and literature, Chris had a life-changing internship experience with the Black Mesa Water Coalition, a Diné environmental justice group based in Flagstaff, Arizona. He drew upon this experience to demonstrate the ceremonial and spiritual implications of food sovereignty—and by extension Indigenous activism— as demonstrated by the restoration of traditional corn fields. “Though places and landscapes play a fundamental role in the fabric of all cultures, Diné people have chosen to actively participate in the interplay between human and nonhuman forces in a way that illuminates the power of place and gives agency to the more-than-human world.”

The Cost of Cheaper Milk

By Don Dennis '82

I’m pretty sure I am the only American milkman in Scotland, the result of my having married a dairy farmer over here on one of the smaller islands. Due to the collapse of the bulk milk price, we began pasteurising and bottling Emma’s milk in returnable glass bottles two years ago, selling it through small village shops in this sparsely populated county. Along the way, we discovered that good-tasting milk has been almost entirely removed from the marketplace in most developed countries.

I’m pretty sure I am the only American milkman in Scotland, the result of my having married a dairy farmer over here on one of the smaller islands. Due to the collapse of the bulk milk price, we began pasteurising and bottling Emma’s milk in returnable glass bottles two years ago, selling it through small village shops in this sparsely populated county. Along the way, we discovered that good-tasting milk has been almost entirely removed from the marketplace in most developed countries.

It was the arrival of the supermarkets, and the accompanying decline in home deliveries of milk, that brought this about. Fifty years ago, milk tasted better because it was pasteurized at a low temperature (63˚C) and held there for 30 minutes. The supermarkets came along and wanted cheaper milk to lure in the customers. And so the dairy processing companies introduced pasteurizing at 73˚C for 15 seconds, which is at least 120 times faster as a process, hence far cheaper. The fact that it drastically harms the taste was not the supermarkets’ concern. They got the cheap milk they wanted.

Something akin to that has happened with organic milk in the US: 80 percent of it is Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) treated (heated to more than 135˚C), so as to give it a six-month shelf life. The supermarkets wouldn’t carry it unless it had that sort of shelf life, as it is too much of a niche item.

In Australia, most milk is pasteurised at 81.6˚C for only two seconds! You can see the trend. Milk is supposed to be as cheap as possible, and so you reduce the costs of farming by having mega-herds of cows that stay indoors 365 days a year and never see grass; and you speed up the pasteurizing process, no matter what the cost is in terms of taste.

Ours is the only commercial dairy in Scotland that pasteurizes milk the old-fashioned way, with the low-temperature protocol. Hence it costs considerably more than supermarket white stuff. And yet we have found that it sells well anywhere we can reach with our distribution. People are continually amazed, and grateful, to find milk that tastes like the milk they had when they were children 50 or more years ago. And the glass bottle is a bonus.

Don Dennis delivers his Wee Isle Dairy whole milk from the isle of Gigha to points in Scotland as far away as Edinburgh, Penicuik, and Peebles. As if that’s not enough, he is also director of the Flower Essence Repertoire Ltd, producing a unique range of flower essences with tropical orchids. Learn more at healingorchids.com. Photos by Don Dennis

On and Off the Hill

New focus on curriculum, new faculty, new library grants, and new connections between old friends at Home Days 2018. It all happens right here at Marlboro and you can read about it in On and Off the Hill.

New focus on curriculum, new faculty, new library grants, and new connections between old friends at Home Days 2018. It all happens right here at Marlboro and you can read about it in On and Off the Hill.

Faculty Reimagine Curriculum

Last summer, a group of Marlboro faculty and staff worked together with a series of consultants to strengthen and adapt the academic program to meet the needs of a new generation of students. Building on the work of task forces from the previous summer, and supported by a generous grant from the Mellon Foundation, their recommendations have been at the root of substantial curricular changes approved by the full faculty in the fall semester, and more changes to come.

The August report of the Reimagining Marlboro summer task force states: “In our work, we have endeavored to build on the quintessential qualities of a Marlboro education in a way that leverages our strengths; responds to the changing times; and provides a firm foundation for Marlboro’s future sustainability in recruitment, retention, and fundraising.”

“The faculty has approved more significant changes to the curriculum in the last six months than it has in the previous 10 years,” says Richard Glezjer, provost and dean of faculty. “We’re not changing Marlboro, or the Plan of Concentration, just making it all clearer and having more even expectations. We’re taking our core strengths and doing them better.”

The proposals from the task force directly address three charges posed to the group by Marlboro’s trustees: to reconsider and revise, if necessary, curricular areas so as to attract and retain more students; to reevaluate Marlboro’s learning goals and teaching practices in light of growing concerns by prospective students and their families regarding how a liberal arts education prepares students for working life after graduation; and to address the changing needs of students as they enter into Marlboro’s highly flexible curricular model. A series of concrete steps to modify the curriculum deftly maintain Marlboro’s celebrated level of student choice while also providing a shared set of expectations.

At the core of these curricular changes is the Marlboro Promise: “At Marlboro College you can prepare for any career you might ever have, by studying what you’re passionate about right now. No matter where your educational path might take you, Marlboro can promise you that you’ll graduate with the skills you need for a life of meaningful work.”

At the core of these curricular changes is the Marlboro Promise: “At Marlboro College you can prepare for any career you might ever have, by studying what you’re passionate about right now. No matter where your educational path might take you, Marlboro can promise you that you’ll graduate with the skills you need for a life of meaningful work.”

The promise includes an articulation of three specific, transferable skills that can be directly correlated with success after graduation, however one chooses to define it. Those skills are: (1) the ability to write with clarity and precision; (2) the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals; and (3) the ability to lead an ambitious project from idea to execution.

These skills will not sound surprising to anyone who has experienced Marlboro. Three longstanding pillars of a Marlboro education—the Clear Writing Requirement, the focus on community governance and civic engagement, and the Plan—speak directly to each of them, respectively. What is new here is a focus on reaching all students with these transformative experiences, and a renewed emphasis on bolstering, documenting, and articulating the skills they support.

“Last summer’s reimagining work created the Marlboro Promise, which is a set of shared curricular goals,” says Kristin Horrigan, professor of dance and gender studies and one of the nine faculty members on the task force. “The faculty’s job for this year is to design and implement the changes that will make the Marlboro Promise a reality for all students. These changes take place in our own classrooms, as well as in the structures that support and guide a student’s four years at Marlboro.”

“The three goals provide us with a much more precise map of the Marlboro territory,” says Meg Mott, professor of politics and another member of the task force. “While we’ve always cohabitated in the land of clear writing, now we dwell in a terrain that includes two other commitments: project management and working with a wide range of individuals.”

Kristin suggests that goal number two, a commitment to teaching all students the skills they need to “live, work, and communicate with a wide range of individuals,” represents the most significant shift in the curriculum. But structural changes that support that commitment are still being drafted by faculty committees and will be debated in the spring, so in a sense the most significant changes are still to come.

“While students at Marlboro have always had the opportunity to gain these skills by participating in community governance and engaging in community life on a small campus, no one was required to participate,” says Kristin. “Let me be clear that the promise does not mean we are now requiring unwilling students to participate in community governance. Rather we will be providing a range of pathways to allow students to foster these skills, and setting one or more checkpoints where students will need to demonstrate their learning.”

“While students at Marlboro have always had the opportunity to gain these skills by participating in community governance and engaging in community life on a small campus, no one was required to participate,” says Kristin. “Let me be clear that the promise does not mean we are now requiring unwilling students to participate in community governance. Rather we will be providing a range of pathways to allow students to foster these skills, and setting one or more checkpoints where students will need to demonstrate their learning.”

Recent additions to the curriculum that will help support and document the goals of the Marlboro Promise include a new first-year seminar, taken by all first-year students, that provides a clear on-ramp to Marlboro’s unique curricular structure. The seminar serves as an introduction to the four-year “progression,” and clearly articulates the skills students will gain at Marlboro.

Other changes are under consideration by faculty this spring, such as an opportunity for reflection and assessment near the end of each student’s four years, before the completion of their Plan of Concentration. A component of their Plan due during their junior 2 or senior 1 semester would help to support more even progress toward completion and also provide valuable finished work in time for graduate school applications.

“Students who wanted to continue on to graduate school were finding they did not have completed components of their Plan in time to submit them with their applications, so they weren’t applying until the following year,” says Richard. “This early component of the Plan would serve that purpose and also provide a point for reflection on the Plan direction and scope.” More proposed changes to the curriculum would assess students’ process toward the three stated goals at every stage of their progression.

“To me, the most significant shift lies in analyzing the Marlboro curriculum across the full four years with an eye to how we can support students at each point along the way,” says Bronwen Tate, professor of writing and literature and task force member. “This means asking questions like, ‘If we’re thinking of the Plan process as one in which students learn to manage a complex project, are we actually providing our students with explicit opportunities to learn these skills or just hoping that they pick them up along the way?’”

Bronwen continues: “As I tell my writing students, some writing difficulties are necessary and useful, while others—writing in isolation, say, or at the last possible minute—are pointless and avoidable. The reimagining work asks how we can reduce unnecessary confusions and pitfalls so that students have the motivation and joy to face the necessary difficulties of learning and growth. As a writing professor, specifically, I’m excited by the college’s reaffirmed commitment to writing and by the willingness of colleagues across the curriculum to learn together how to be better writing teachers.”

Where the rubber hits the road, so to speak, is of course in the classroom. For many teachers, the Marlboro Promise will mean a substantial shift in how they teach, document, and assess their students, while others consider the changes less dramatic.

Where the rubber hits the road, so to speak, is of course in the classroom. For many teachers, the Marlboro Promise will mean a substantial shift in how they teach, document, and assess their students, while others consider the changes less dramatic.

“Each of our classes will have to help develop students’ abilities in one or more of these areas—so I have to decide which courses will emphasize which skills,” says Todd Smith, chemistry professor. “I think the biggest change will involve reviewing each of our individual curricula to ensure that it has the structure to support the skill development, while also providing specific content.”

“Instead of using finished essays as the sole means of evaluating mastery of course content, I now offer the option of generating a final presentation for the community that sets out the controversies of the topic through a well-coordinated panel of confident speakers,” says Meg. “The panel operates as a group essay, one that could easily turn into a google doc. Even though writing did not occur, the skills needed to produce a strong piece of writing are given sufficient time.”

“Will it change the way I teach? Not really,” says Adam Franklin-Lyons, professor of history and environmental studies and a member of the task force. Adam expressed some concern that the reimagining made Marlboro look more like other schools, “although Marlboro is and will always remain a unique institution and community.’”

Amer Latif, professor of religion and task force member, says, “The Marlboro Promise allows me to frame the usual duality of instrumentality (transferable skills, making a living, jobs, etc.) and ‘learning as its own end’ in a non-dual manner. I’m very happy with this formulation. I have introduced the promise in all of my classes and am using the framework for situating the activities we do in class. For example, I have institutionalized a formal ‘setting of intention’ at the beginning of each class where students take turns to lead us in creating a space for meaningful conversation. I speak of this activity as training in leadership and reiterate the values and skills associated with the small things we do in class.”

“I think the most significant ‘change’ to the curriculum is not necessarily a change but rather an intentional commitment to the values that the college has always held dear—engaged citizenship, clear communication, and Plan,” says Jaime Tanner, biology professor. “In particular, the articulation of our value for engaged citizenship as part of our curriculum challenges each of us as faculty to evaluate not just what we are teaching but how we ask our students to engage with one another through our courses, how to foster collaboration and encourage dialogue even in the face of disagreement.”

Although it was not originally part of the Reimagining Marlboro process, another important change to the curriculum this year was the adoption of “fields of concentration” to replace the “degree fields” that are attached to Plans. While degree fields were associated with specific learning goals devised by the faculty, the fields of concentration will have goals defined by students specific to their area of research. They will include the degree fields you may be familiar with but can include additional fields subject to approval by faculty.

Although it was not originally part of the Reimagining Marlboro process, another important change to the curriculum this year was the adoption of “fields of concentration” to replace the “degree fields” that are attached to Plans. While degree fields were associated with specific learning goals devised by the faculty, the fields of concentration will have goals defined by students specific to their area of research. They will include the degree fields you may be familiar with but can include additional fields subject to approval by faculty.

“The introduction of fields of concentration has been a long time coming, and is more in keeping with Marlboro’s student-driven pedagogy than the rigid degree fields,” says Richard. “The fact that it has been approved in the same breath, almost, as the Marlboro Promise reinforces and confirms the move. In the end, the specific field you choose is not as important as the process and the skills acquired along the way.”

The Reimagining Marlboro effort addresses the longstanding concern that while the Marlboro experience is extraordinary, the college is not delivering that experience evenly to every student. For Marlboro to succeed and thrive, it must be able to make that promise to every Marlboro student—not just those students who become our success stories, buying into our model and stepping up to the challenge of their own initiative. Although still a work in progress, the ongoing reimagining will establish the milestones or “hand-holds” (in the rock-climbing sense, not the crossing-the-street sense) to make that promise a reality, with enormous implications for student recruitment, retention, graduation rates, and alumni engagement.

Creating Space for Critical Conversations

In December, faculty members participated in a workshop in civil discourse designed to support their commitment to the second goal of the Marlboro Promise: the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals. Sponsored by the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force, the faculty development workshop was titled “Creating Space for Critical Conversations” and was facilitated by Renee Wells, director of education for equity and inclusion at Middlebury College. The workshop was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

In December, faculty members participated in a workshop in civil discourse designed to support their commitment to the second goal of the Marlboro Promise: the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals. Sponsored by the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force, the faculty development workshop was titled “Creating Space for Critical Conversations” and was facilitated by Renee Wells, director of education for equity and inclusion at Middlebury College. The workshop was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

“Having Renee Wells on campus was a valuable opportunity for us to work toward fulfilling our commitment to the Marlboro Promise and for us to engage difficult pedagogical opportunities appropriately,” said William Ransom, sculpture professor and member of the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force. “The workshop offered strategies to create more inclusive classroom spaces.”

The training explored the challenges associated with class discussion, and helped faculty develop skills to set the tone for critical conversations and to intervene and respond when comments or questions result in harm. Key concepts addressed included establishing expectations and intended outcomes for dialogue, and helping students to analyze not only their own ideas and the ideas of others but the impact of those ideas on others. Faculty left with a better sense of how to frame these issues for students, help students critically self-reflect, and respond to microaggressions when they occur.

Ian McManus Asks Big Political Questions

“I’m really interested in having students understand the complex world in which we live,” says Ian McManus, who joined Marlboro this fall to teach comparative politics and political economy. “We live in societies where economic influences, political institutions, social norms, and culture shape the world around us. So I’m interested in helping students develop the skills to critically analyze that world.”

“I’m really interested in having students understand the complex world in which we live,” says Ian McManus, who joined Marlboro this fall to teach comparative politics and political economy. “We live in societies where economic influences, political institutions, social norms, and culture shape the world around us. So I’m interested in helping students develop the skills to critically analyze that world.”

Ian came to Marlboro from a fellowship in social policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science and a postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of Lisbon. He has a PhD from Northeastern University, where his doctoral dissertation explored the effects of the global financial crisis across welfare states. He teaches courses that offer cross-national perspectives on pressing political, economic, and social concerns, from gender equality to political polarization, subjects that he is passionate about.

For example, in the fall he taught a course on the Politics of Global Inequality. “Students looked at global inequality from a historical context, then saw how it is now, then asked big questions,” Ian says. “Why is it like that? What’s driving inequality? What are the causes and consequences of inequality? And then, ultimately, what are some things we could do to address this issue? So the course is about asking big questions, and trying to have a meaningful impact in the world too.” He also taught a course on populist politics around the world called Rage Against the Machine: Populist Politics in the Age of Trump and Brexit.

Ian enjoys inspiring students to become engaged learners and active participants in our complex political world. He encourages them to bring their own experiences and interests to the classroom, and by doing so contribute to each other’s learning experience. He feels that this creates an environment where the class can explore even the knottiest of questions.

“Ideally you come to class with your own interests and passions, and as you learn more about the world, about policies and outcomes, you can start to think about ‘How can I apply what I’ve learned to issues that I’m passionate about in order to shape the world in important ways?’ I’m trying to get students involved. For instance, I know that there are local community projects that deal with issues like poverty and inequality, so after thinking about global inequality you could also look at inequality in your own community.”

As a politics professor, Ian has a special interest in shared governance at Marlboro and looks forward to being more involved in committees and Town Meeting. His own classes stand to benefit greatly from the college’s emphasis on student engagement in the campus community.

“It’s one thing to be here in person, physically on campus, and another to be engaged in the processes of the college,” Ian says. He is impressed by the diversity of opinion he finds in the classroom, as well as at Town Meeting, in a rural area that one might assume was homogenous. “This idea of direct democracy—being able to have a say in decisions that affect students, faculty, staff, and the whole community— is an exciting one and there is a real focus on this principle at Marlboro, which is really nice. Given Marlboro’s size we are able to engage in democracy and community decision-making in meaningful ways that larger schools couldn’t.”

Meanwhile, Ian is also working on a book based on his dissertation as well as several further articles on the politics of social and economic policymaking across countries. “This work addresses issues like the distributional effects of the Great Recession, the effects of international institutions on domestic policies, the influence of political parties and ideologies on social spending, and the negative effects of inequality on economic growth and social well-being.”

As fate would have it, Ian actually grew up just a stone’s throw away, in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, so has known about Marlboro—“this intentionally small learning community”—for many years. It feels like he has come full circle, after teaching classes with 150 students, to be a part of Marlboro’s more personal educational experience. Besides, he says, “I’ve lived in a lot of different places, but autumn in New England is pretty hard to beat.”

Rituparna Mitra Decolonizes Literature

“I was drawn to Marlboro because it was an intentionally small school with an emphasis on teaching, and an openness to political aspects of literature,” says Rituparna Mitra, who joined Marlboro as professor of literature and writing in the fall. “But once I came here, then I noticed other things like the community, the way people interacted with one another—there was this closeness and at the same time freshness that I liked. And the independence that the students are encouraged to have—thinking of a long-term project, investing in it—that was something that struck me a lot. It’s a rare thing to find elsewhere.”

“I was drawn to Marlboro because it was an intentionally small school with an emphasis on teaching, and an openness to political aspects of literature,” says Rituparna Mitra, who joined Marlboro as professor of literature and writing in the fall. “But once I came here, then I noticed other things like the community, the way people interacted with one another—there was this closeness and at the same time freshness that I liked. And the independence that the students are encouraged to have—thinking of a long-term project, investing in it—that was something that struck me a lot. It’s a rare thing to find elsewhere.”

Rituparna has more than a decade of experience teaching literature and writing in both the US and India, including at Michigan State University where she received her PhD. Her dissertation examined South Asian representations of trauma from the Partition of 1947 and subsequent Hindu-Muslim conflict in India, offering a postcolonial and global understanding of what has mostly been a Eurocentric narrative. Rituparna’s expertise in the areas of global Anglophone literature, social and environmental justice, displacement and migration, and gender and ethnicity brings a transnational perspective to the exploration of literature and writing for Marlboro students.

“I’m here to teach teach global literature as well as postcolonial literature with a deep emphasis on colonization, and so my literature courses definitely address that element,” says Rituparna. In the fall she taught a course on Transnational and Diasporic Narratives, looking at the ways in which the history of colonization and cultural collisions continue to resonate in the way people think about themselves and their place in the world. She also taught a writing seminar on Narratives of Trauma and Witnessing.

“Traumas are often seen through an individual lens, and the Holocaust has been central to the way we think about shared trauma, especially in academics. So, I start at the Holocaust, but then I move on to postcolonialism traumas. I encourage people to think comparatively.” In the spring, Rituparna is excited to be teaching a course on the contemporary global novel. “We’ll be looking a lot at what makes a novel global, and what other worlds are possible.”

Rituparna has had to adjust to smaller class sizes, after teaching in larger classrooms for many years. She says that having fewer speakers in the room pushes her more as a teacher, and demands that she is on her toes at all times. On the other hand, when everyone is fully engaged it is like nothing she’s ever experienced before.

“It’s absolutely fabulous to have just six people in a room, but with an explosion of insights,” says Rituparna. “It’s such an intimate setting, with everybody that involved. I enjoy the different insights they all bring from their different Plans. They have so much experience already, and they’re sharing it from each of their perspectives. As a teacher I’m still constantly learning.”

As far as her own scholarly activities, Rituparna is currently preparing a book manuscript based on her dissertation, titled Postcolonial Trauma in South Asia: Body, Memory, and Displacement in Literature. One chapter has already been published in the edited collection The Postcolonial World, and another is to be published in the forthcoming Beyond Partition: Mediascapes and Literature in Post-colonial India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Rituparna is also working on a second book project that examines representations of global terrorism in South Asian Anglophone literature, where terrorism is linked to the failures of the postcolonial state and to uneven globalization.

Rituparna finds great inspiration in the peace and natural beauty of Marlboro, having spent most of her adult life in more urban areas. “Just being in a place that’s this beautiful, even when it’s gray and rainy, nurtures me in a sense. It feels magical, and nourishes creativity. I love that. So, on one hand, just the place— the physicality—but also the people I interact with. It’s such a joy to have intelligent, open-minded, aware people. I’m actually getting spoiled.”

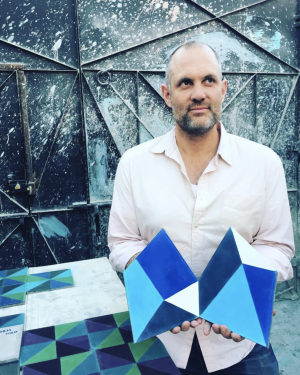

William Ransom: Engaging with Materials

“Sculpture is often used as an umbrella term encompassing everything from carving stone or modeling clay to performance and video work—all of those things that exist beyond two-dimensional art,” says William Ransom, who joined Marlboro to teach sculpture and visual arts in the fall. “For myself, I have taught things that reach across that spectrum, all the way from direct material engagement to more installation-based stuff.”

“Sculpture is often used as an umbrella term encompassing everything from carving stone or modeling clay to performance and video work—all of those things that exist beyond two-dimensional art,” says William Ransom, who joined Marlboro to teach sculpture and visual arts in the fall. “For myself, I have taught things that reach across that spectrum, all the way from direct material engagement to more installation-based stuff.”

William was already familiar with Marlboro from years ago, when he was a Bennington College student and came to campus to play their perennial soccer rival. He also grew up in Strafford, Vermont, so after ten years on the West Coast, getting his MFA from Claremont Graduate University and teaching at Pomona College, Cal State San Bernardino, and California Institute of the Arts, he was eager to return to the Green Mountain State. A yearlong visiting professorship at Middlebury College only whet his appetite.

“Having grown up in Vermont, and now having kids, I started kind of stalking Marlboro College—in the best way—looking for job postings,” says William. “And when I saw the posting and dug a little bit deeper into the program, I was really smitten with the idea. The small size appeals to me because I like having a developed relationship with my students surrounding their work. That’s really valuable, and at bigger schools it’s hard to come by.”

William also likes the ability to plan his own curriculum and the potential for cross-pollination with other faculty members with overlapping interests. “One of the benefits about being in a small place is that nimbleness.”

When introducing students to sculpture, William starts from an embodied experience of material, asserting that there is a lot of useful information to be gleaned from paying attention to materials and direct material engagement with one’s hands and body. He often likes to start with clay because it is so receptive to manipulation in a way that wood or stone is not.

“Clay is immediately reflective of your engagement with it, and that immediacy gives feedback in the form of knowledge built into your body, if you are paying attention. I feel like students respond very well to the directness of that, as a point of entry. As you get further up on the ladder of learning about sculpture, the direct engagement leads to conceptual engagement, and materials run the spectrum from stone carving to installation, social sculpture, and performance-based work. I feel like material engagement is the way to open the door to those other more conceptually driven works and interacting with the audience—the caliber of student work is improved greatly by a broader material understanding.”

William’s own work often concerns issues of race and social justice, as well as sustainability, interaction with the natural world, and agricultural experience. He works with wood a lot, often testing its material potential in ephemeral installations that evoke dynamic tension between elements and invite audience participation.

“I really like the potential of the visceral encounter for the viewer,” says William, who has exhibited his work in galleries across the country, from New York, Detroit, and Chicago to California. Most recently, he was included in group exhibitions in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California, and a solo exhibition titled Hem n’ Haw, in Hudson, New York. William was awarded a Windgate Fellowship at Vermont Studio Center in 2015, in addition to several other fellowships over the years.

William is excited about a class he’s teaching this spring close to his own interests, called Art’s Ghost: The Ephemeral and Letting Go. In addition to exploring the rise of ephemerality in contemporary art history, students will be exploring materials that, by design, don’t last— from snow and ice to installation and performance art.

“We’ll be thinking pretty broadly about what it means to make something that has a brief window of time in which it can be experienced or enjoyed, and questioning the preciousness of objects,” says William.

A self-described biracial farm-boy, William recognizes that there are some drawbacks to relocating from southern California to Vermont, notably the relative scarcity of cultural institutions and opportunities and the lack of racial diversity. But he is certain that Marlboro’s geographic location should not hinder students’ access to culture. “I have been pleasantly surprised, actually, at how much more diverse Vermont has become since I was a kid here.”

Library Rocks NEH Grants

The Rice-Aron Library was the proud recipient of two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) this year. Together, they stand to increase the library’s impact within the local community and make its valuable archives more accessible.

The first was a joint NEH and American Library Association grant to take part in the Great Stories Club, a program that supports reading and discussion programs for underserved teens. Partnering with the Boys and Girls Club of Brattleboro, Rice-Aron Library was one of 100 libraries in the US selected for this grant, one of only five college libraries, and the only grantee chosen in Vermont.

“We are excited to start our book club in January, with the theme ‘What Makes a Hero: Self, Society, and Rising to the Occasion,’” says library director Beth Ruane. “The books include an amazing range of perspectives, from Black Panther to Art Spiegelman’s Maus II, chosen to inspire teens to consider big questions about the world and their place in it.”

The second NEH award is a Preservation Assistance Grant, designed to help small institutions improve their ability to preserve and care for significant humanities collections. The Rice-Aron archives are one such collection, composed of printed materials on paper, images, audio and video tapes, and historical ephemera stretching back to the founding of the college.

“Marlboro’s first students, most of whom were veterans, indelibly shaped Marlboro’s uniquely self-directed, self-governed, and self-reliant identity,” says Beth. “These primary source materials have great value to scholars and students studying in a wide range of areas, including the history of higher education in America, the post-WWII era, and the veteran experience.”

Rice-Aron’s archives were the subject of last year’s course titled History of Universities and the Liberal Arts, which focused on the history of Marlboro and its place in wider debates about the role and purpose of higher education. Students spent every other Thursday working in the archives to create more-specific subject categories for ease of finding, and shared some rare discoveries with the community through social media.

“Unfortunately, Marlboro has never been in a position to have a full-time archivist on its staff,” says Beth. “As a result, though the collecting of materials created by students, faculty, and administrative and departmental staff has been enthusiastic, knowing exactly what is held in the archives, let alone locating an item in a timely fashion, is nearly impossible.”

The first step of an ambitious project to improve stewardship and increase internal and external access to the college archives, the NEH grant will enable Beth to take classes at Simmons College in the area of Special Collections and Archives. “This training will position me to be a more effective steward of the college’s archives, able to develop realistic and appropriate planning for the assessment, processing, and ongoing care of this important collection.”

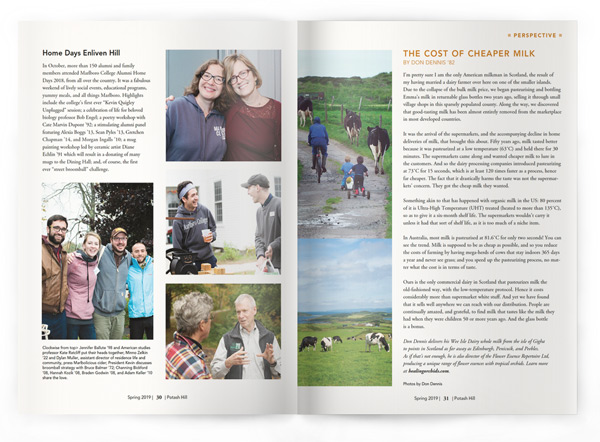

Home Days Enliven Hill

In October, more than 150 alumni and family members attended Marlboro College Alumni Home Days 2018, from all over the country. It was a fabulous weekend of lively social events, educational programs, yummy meals, and all things Marlboro. Highlights include the college’s first ever “Kevin Quigley Unplugged” session; a celebration of life for beloved biology professor Bob Engel; a poetry workshop with Cate Marvin Dupont ’92; a stimulating alumni panel featuring Alexia Boggs ’13, Sean Pyles ’13, Gretchen Chapman ’14, and Morgan Ingalls ’10; a mug painting workshop led by ceramic artist Diane Echlin ’91 which resulted in a donating of many mugs to the Dining Hall; and, of course, the first ever “street broomball” challenge.

Photos on left page above, clockwise from top> Jennifer Ballute ’98 and American studies professor Kate Ratcliff put their heads together; Minno Zelkin ’22 and Dylan Muller, assistant director of residence life and community, press Marlbolicious cider; President Kevin discusses broomball strategy with Bruce Balmer ’72; Channing Bickford ’08, Hannah Kozik ’08, Braden Godwin ’08, and Adam Keller ’10 share the love.

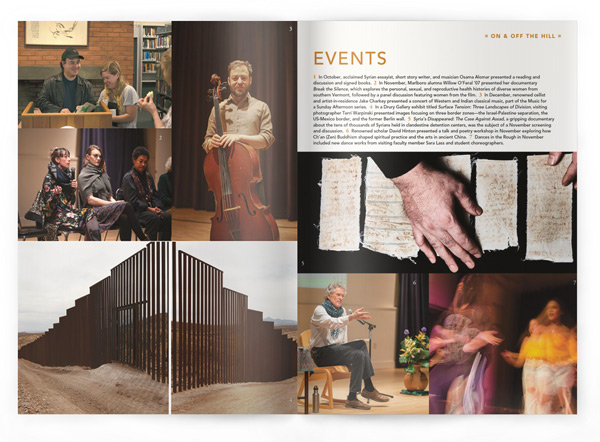

Events

1 In October, acclaimed Syrian essayist, short story writer, and musician Osama Alomar presented a reading and discussion and signed books. 2 In November, Marlboro alumna Willow O’Feral ’07 presented her documentary Break the Silence, which explores the personal, sexual, and reproductive health histories of diverse women from southern Vermont, followed by a panel discussion featuring women from the film. 3 In December, renowned cellist and artist-in-residence Jake Charkey presented a concert of Western and Indian classical music, part of the Music for a Sunday Afternoon series. 4 In a Drury Gallery exhibit titled Surface Tension: Three Landscapes of Division, visiting photographer Terri Warpinski presented images focusing on three border zones—the Israel-Palestine separation, the US-Mexico border, and the former Berlin wall. 5 Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad, a gripping documentary about the tens of thousands of Syrians held in clandestine detention centers, was the subject of a November screening and discussion. 6 Renowned scholar David Hinton presented a talk and poetry workshop in November exploring how Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism shaped spiritual practice and the arts in ancient China. 7 Dances in the Rough in November included new dance works from visiting faculty member Sara Lass and student choreographers.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

In December, Danielle Scobey ’22 sat down with American studies professor Kate Ratcliff to talk about oral history, aging, and radical decontextualization in America. You can read the whole interview at potash.marlboro.edu/ratcliff.

Danielle: How would you describe what you teach here?