On and Off the Hill

New focus on curriculum, new faculty, new library grants, and new connections between old friends at Home Days 2018. It all happens right here at Marlboro and you can read about it in On and Off the Hill.

New focus on curriculum, new faculty, new library grants, and new connections between old friends at Home Days 2018. It all happens right here at Marlboro and you can read about it in On and Off the Hill.

Faculty Reimagine Curriculum

Last summer, a group of Marlboro faculty and staff worked together with a series of consultants to strengthen and adapt the academic program to meet the needs of a new generation of students. Building on the work of task forces from the previous summer, and supported by a generous grant from the Mellon Foundation, their recommendations have been at the root of substantial curricular changes approved by the full faculty in the fall semester, and more changes to come.

The August report of the Reimagining Marlboro summer task force states: “In our work, we have endeavored to build on the quintessential qualities of a Marlboro education in a way that leverages our strengths; responds to the changing times; and provides a firm foundation for Marlboro’s future sustainability in recruitment, retention, and fundraising.”

“The faculty has approved more significant changes to the curriculum in the last six months than it has in the previous 10 years,” says Richard Glezjer, provost and dean of faculty. “We’re not changing Marlboro, or the Plan of Concentration, just making it all clearer and having more even expectations. We’re taking our core strengths and doing them better.”

The proposals from the task force directly address three charges posed to the group by Marlboro’s trustees: to reconsider and revise, if necessary, curricular areas so as to attract and retain more students; to reevaluate Marlboro’s learning goals and teaching practices in light of growing concerns by prospective students and their families regarding how a liberal arts education prepares students for working life after graduation; and to address the changing needs of students as they enter into Marlboro’s highly flexible curricular model. A series of concrete steps to modify the curriculum deftly maintain Marlboro’s celebrated level of student choice while also providing a shared set of expectations.

At the core of these curricular changes is the Marlboro Promise: “At Marlboro College you can prepare for any career you might ever have, by studying what you’re passionate about right now. No matter where your educational path might take you, Marlboro can promise you that you’ll graduate with the skills you need for a life of meaningful work.”

At the core of these curricular changes is the Marlboro Promise: “At Marlboro College you can prepare for any career you might ever have, by studying what you’re passionate about right now. No matter where your educational path might take you, Marlboro can promise you that you’ll graduate with the skills you need for a life of meaningful work.”

The promise includes an articulation of three specific, transferable skills that can be directly correlated with success after graduation, however one chooses to define it. Those skills are: (1) the ability to write with clarity and precision; (2) the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals; and (3) the ability to lead an ambitious project from idea to execution.

These skills will not sound surprising to anyone who has experienced Marlboro. Three longstanding pillars of a Marlboro education—the Clear Writing Requirement, the focus on community governance and civic engagement, and the Plan—speak directly to each of them, respectively. What is new here is a focus on reaching all students with these transformative experiences, and a renewed emphasis on bolstering, documenting, and articulating the skills they support.

“Last summer’s reimagining work created the Marlboro Promise, which is a set of shared curricular goals,” says Kristin Horrigan, professor of dance and gender studies and one of the nine faculty members on the task force. “The faculty’s job for this year is to design and implement the changes that will make the Marlboro Promise a reality for all students. These changes take place in our own classrooms, as well as in the structures that support and guide a student’s four years at Marlboro.”

“The three goals provide us with a much more precise map of the Marlboro territory,” says Meg Mott, professor of politics and another member of the task force. “While we’ve always cohabitated in the land of clear writing, now we dwell in a terrain that includes two other commitments: project management and working with a wide range of individuals.”

Kristin suggests that goal number two, a commitment to teaching all students the skills they need to “live, work, and communicate with a wide range of individuals,” represents the most significant shift in the curriculum. But structural changes that support that commitment are still being drafted by faculty committees and will be debated in the spring, so in a sense the most significant changes are still to come.

“While students at Marlboro have always had the opportunity to gain these skills by participating in community governance and engaging in community life on a small campus, no one was required to participate,” says Kristin. “Let me be clear that the promise does not mean we are now requiring unwilling students to participate in community governance. Rather we will be providing a range of pathways to allow students to foster these skills, and setting one or more checkpoints where students will need to demonstrate their learning.”

“While students at Marlboro have always had the opportunity to gain these skills by participating in community governance and engaging in community life on a small campus, no one was required to participate,” says Kristin. “Let me be clear that the promise does not mean we are now requiring unwilling students to participate in community governance. Rather we will be providing a range of pathways to allow students to foster these skills, and setting one or more checkpoints where students will need to demonstrate their learning.”

Recent additions to the curriculum that will help support and document the goals of the Marlboro Promise include a new first-year seminar, taken by all first-year students, that provides a clear on-ramp to Marlboro’s unique curricular structure. The seminar serves as an introduction to the four-year “progression,” and clearly articulates the skills students will gain at Marlboro.

Other changes are under consideration by faculty this spring, such as an opportunity for reflection and assessment near the end of each student’s four years, before the completion of their Plan of Concentration. A component of their Plan due during their junior 2 or senior 1 semester would help to support more even progress toward completion and also provide valuable finished work in time for graduate school applications.

“Students who wanted to continue on to graduate school were finding they did not have completed components of their Plan in time to submit them with their applications, so they weren’t applying until the following year,” says Richard. “This early component of the Plan would serve that purpose and also provide a point for reflection on the Plan direction and scope.” More proposed changes to the curriculum would assess students’ process toward the three stated goals at every stage of their progression.

“To me, the most significant shift lies in analyzing the Marlboro curriculum across the full four years with an eye to how we can support students at each point along the way,” says Bronwen Tate, professor of writing and literature and task force member. “This means asking questions like, ‘If we’re thinking of the Plan process as one in which students learn to manage a complex project, are we actually providing our students with explicit opportunities to learn these skills or just hoping that they pick them up along the way?’”

Bronwen continues: “As I tell my writing students, some writing difficulties are necessary and useful, while others—writing in isolation, say, or at the last possible minute—are pointless and avoidable. The reimagining work asks how we can reduce unnecessary confusions and pitfalls so that students have the motivation and joy to face the necessary difficulties of learning and growth. As a writing professor, specifically, I’m excited by the college’s reaffirmed commitment to writing and by the willingness of colleagues across the curriculum to learn together how to be better writing teachers.”

Where the rubber hits the road, so to speak, is of course in the classroom. For many teachers, the Marlboro Promise will mean a substantial shift in how they teach, document, and assess their students, while others consider the changes less dramatic.

Where the rubber hits the road, so to speak, is of course in the classroom. For many teachers, the Marlboro Promise will mean a substantial shift in how they teach, document, and assess their students, while others consider the changes less dramatic.

“Each of our classes will have to help develop students’ abilities in one or more of these areas—so I have to decide which courses will emphasize which skills,” says Todd Smith, chemistry professor. “I think the biggest change will involve reviewing each of our individual curricula to ensure that it has the structure to support the skill development, while also providing specific content.”

“Instead of using finished essays as the sole means of evaluating mastery of course content, I now offer the option of generating a final presentation for the community that sets out the controversies of the topic through a well-coordinated panel of confident speakers,” says Meg. “The panel operates as a group essay, one that could easily turn into a google doc. Even though writing did not occur, the skills needed to produce a strong piece of writing are given sufficient time.”

“Will it change the way I teach? Not really,” says Adam Franklin-Lyons, professor of history and environmental studies and a member of the task force. Adam expressed some concern that the reimagining made Marlboro look more like other schools, “although Marlboro is and will always remain a unique institution and community.’”

Amer Latif, professor of religion and task force member, says, “The Marlboro Promise allows me to frame the usual duality of instrumentality (transferable skills, making a living, jobs, etc.) and ‘learning as its own end’ in a non-dual manner. I’m very happy with this formulation. I have introduced the promise in all of my classes and am using the framework for situating the activities we do in class. For example, I have institutionalized a formal ‘setting of intention’ at the beginning of each class where students take turns to lead us in creating a space for meaningful conversation. I speak of this activity as training in leadership and reiterate the values and skills associated with the small things we do in class.”

“I think the most significant ‘change’ to the curriculum is not necessarily a change but rather an intentional commitment to the values that the college has always held dear—engaged citizenship, clear communication, and Plan,” says Jaime Tanner, biology professor. “In particular, the articulation of our value for engaged citizenship as part of our curriculum challenges each of us as faculty to evaluate not just what we are teaching but how we ask our students to engage with one another through our courses, how to foster collaboration and encourage dialogue even in the face of disagreement.”

Although it was not originally part of the Reimagining Marlboro process, another important change to the curriculum this year was the adoption of “fields of concentration” to replace the “degree fields” that are attached to Plans. While degree fields were associated with specific learning goals devised by the faculty, the fields of concentration will have goals defined by students specific to their area of research. They will include the degree fields you may be familiar with but can include additional fields subject to approval by faculty.

Although it was not originally part of the Reimagining Marlboro process, another important change to the curriculum this year was the adoption of “fields of concentration” to replace the “degree fields” that are attached to Plans. While degree fields were associated with specific learning goals devised by the faculty, the fields of concentration will have goals defined by students specific to their area of research. They will include the degree fields you may be familiar with but can include additional fields subject to approval by faculty.

“The introduction of fields of concentration has been a long time coming, and is more in keeping with Marlboro’s student-driven pedagogy than the rigid degree fields,” says Richard. “The fact that it has been approved in the same breath, almost, as the Marlboro Promise reinforces and confirms the move. In the end, the specific field you choose is not as important as the process and the skills acquired along the way.”

The Reimagining Marlboro effort addresses the longstanding concern that while the Marlboro experience is extraordinary, the college is not delivering that experience evenly to every student. For Marlboro to succeed and thrive, it must be able to make that promise to every Marlboro student—not just those students who become our success stories, buying into our model and stepping up to the challenge of their own initiative. Although still a work in progress, the ongoing reimagining will establish the milestones or “hand-holds” (in the rock-climbing sense, not the crossing-the-street sense) to make that promise a reality, with enormous implications for student recruitment, retention, graduation rates, and alumni engagement.

Creating Space for Critical Conversations

In December, faculty members participated in a workshop in civil discourse designed to support their commitment to the second goal of the Marlboro Promise: the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals. Sponsored by the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force, the faculty development workshop was titled “Creating Space for Critical Conversations” and was facilitated by Renee Wells, director of education for equity and inclusion at Middlebury College. The workshop was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

In December, faculty members participated in a workshop in civil discourse designed to support their commitment to the second goal of the Marlboro Promise: the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals. Sponsored by the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force, the faculty development workshop was titled “Creating Space for Critical Conversations” and was facilitated by Renee Wells, director of education for equity and inclusion at Middlebury College. The workshop was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

“Having Renee Wells on campus was a valuable opportunity for us to work toward fulfilling our commitment to the Marlboro Promise and for us to engage difficult pedagogical opportunities appropriately,” said William Ransom, sculpture professor and member of the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force. “The workshop offered strategies to create more inclusive classroom spaces.”

The training explored the challenges associated with class discussion, and helped faculty develop skills to set the tone for critical conversations and to intervene and respond when comments or questions result in harm. Key concepts addressed included establishing expectations and intended outcomes for dialogue, and helping students to analyze not only their own ideas and the ideas of others but the impact of those ideas on others. Faculty left with a better sense of how to frame these issues for students, help students critically self-reflect, and respond to microaggressions when they occur.

Ian McManus Asks Big Political Questions

“I’m really interested in having students understand the complex world in which we live,” says Ian McManus, who joined Marlboro this fall to teach comparative politics and political economy. “We live in societies where economic influences, political institutions, social norms, and culture shape the world around us. So I’m interested in helping students develop the skills to critically analyze that world.”

“I’m really interested in having students understand the complex world in which we live,” says Ian McManus, who joined Marlboro this fall to teach comparative politics and political economy. “We live in societies where economic influences, political institutions, social norms, and culture shape the world around us. So I’m interested in helping students develop the skills to critically analyze that world.”

Ian came to Marlboro from a fellowship in social policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science and a postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of Lisbon. He has a PhD from Northeastern University, where his doctoral dissertation explored the effects of the global financial crisis across welfare states. He teaches courses that offer cross-national perspectives on pressing political, economic, and social concerns, from gender equality to political polarization, subjects that he is passionate about.

For example, in the fall he taught a course on the Politics of Global Inequality. “Students looked at global inequality from a historical context, then saw how it is now, then asked big questions,” Ian says. “Why is it like that? What’s driving inequality? What are the causes and consequences of inequality? And then, ultimately, what are some things we could do to address this issue? So the course is about asking big questions, and trying to have a meaningful impact in the world too.” He also taught a course on populist politics around the world called Rage Against the Machine: Populist Politics in the Age of Trump and Brexit.

Ian enjoys inspiring students to become engaged learners and active participants in our complex political world. He encourages them to bring their own experiences and interests to the classroom, and by doing so contribute to each other’s learning experience. He feels that this creates an environment where the class can explore even the knottiest of questions.

“Ideally you come to class with your own interests and passions, and as you learn more about the world, about policies and outcomes, you can start to think about ‘How can I apply what I’ve learned to issues that I’m passionate about in order to shape the world in important ways?’ I’m trying to get students involved. For instance, I know that there are local community projects that deal with issues like poverty and inequality, so after thinking about global inequality you could also look at inequality in your own community.”

As a politics professor, Ian has a special interest in shared governance at Marlboro and looks forward to being more involved in committees and Town Meeting. His own classes stand to benefit greatly from the college’s emphasis on student engagement in the campus community.

“It’s one thing to be here in person, physically on campus, and another to be engaged in the processes of the college,” Ian says. He is impressed by the diversity of opinion he finds in the classroom, as well as at Town Meeting, in a rural area that one might assume was homogenous. “This idea of direct democracy—being able to have a say in decisions that affect students, faculty, staff, and the whole community— is an exciting one and there is a real focus on this principle at Marlboro, which is really nice. Given Marlboro’s size we are able to engage in democracy and community decision-making in meaningful ways that larger schools couldn’t.”

Meanwhile, Ian is also working on a book based on his dissertation as well as several further articles on the politics of social and economic policymaking across countries. “This work addresses issues like the distributional effects of the Great Recession, the effects of international institutions on domestic policies, the influence of political parties and ideologies on social spending, and the negative effects of inequality on economic growth and social well-being.”

As fate would have it, Ian actually grew up just a stone’s throw away, in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, so has known about Marlboro—“this intentionally small learning community”—for many years. It feels like he has come full circle, after teaching classes with 150 students, to be a part of Marlboro’s more personal educational experience. Besides, he says, “I’ve lived in a lot of different places, but autumn in New England is pretty hard to beat.”

Rituparna Mitra Decolonizes Literature

“I was drawn to Marlboro because it was an intentionally small school with an emphasis on teaching, and an openness to political aspects of literature,” says Rituparna Mitra, who joined Marlboro as professor of literature and writing in the fall. “But once I came here, then I noticed other things like the community, the way people interacted with one another—there was this closeness and at the same time freshness that I liked. And the independence that the students are encouraged to have—thinking of a long-term project, investing in it—that was something that struck me a lot. It’s a rare thing to find elsewhere.”

“I was drawn to Marlboro because it was an intentionally small school with an emphasis on teaching, and an openness to political aspects of literature,” says Rituparna Mitra, who joined Marlboro as professor of literature and writing in the fall. “But once I came here, then I noticed other things like the community, the way people interacted with one another—there was this closeness and at the same time freshness that I liked. And the independence that the students are encouraged to have—thinking of a long-term project, investing in it—that was something that struck me a lot. It’s a rare thing to find elsewhere.”

Rituparna has more than a decade of experience teaching literature and writing in both the US and India, including at Michigan State University where she received her PhD. Her dissertation examined South Asian representations of trauma from the Partition of 1947 and subsequent Hindu-Muslim conflict in India, offering a postcolonial and global understanding of what has mostly been a Eurocentric narrative. Rituparna’s expertise in the areas of global Anglophone literature, social and environmental justice, displacement and migration, and gender and ethnicity brings a transnational perspective to the exploration of literature and writing for Marlboro students.

“I’m here to teach teach global literature as well as postcolonial literature with a deep emphasis on colonization, and so my literature courses definitely address that element,” says Rituparna. In the fall she taught a course on Transnational and Diasporic Narratives, looking at the ways in which the history of colonization and cultural collisions continue to resonate in the way people think about themselves and their place in the world. She also taught a writing seminar on Narratives of Trauma and Witnessing.

“Traumas are often seen through an individual lens, and the Holocaust has been central to the way we think about shared trauma, especially in academics. So, I start at the Holocaust, but then I move on to postcolonialism traumas. I encourage people to think comparatively.” In the spring, Rituparna is excited to be teaching a course on the contemporary global novel. “We’ll be looking a lot at what makes a novel global, and what other worlds are possible.”

Rituparna has had to adjust to smaller class sizes, after teaching in larger classrooms for many years. She says that having fewer speakers in the room pushes her more as a teacher, and demands that she is on her toes at all times. On the other hand, when everyone is fully engaged it is like nothing she’s ever experienced before.

“It’s absolutely fabulous to have just six people in a room, but with an explosion of insights,” says Rituparna. “It’s such an intimate setting, with everybody that involved. I enjoy the different insights they all bring from their different Plans. They have so much experience already, and they’re sharing it from each of their perspectives. As a teacher I’m still constantly learning.”

As far as her own scholarly activities, Rituparna is currently preparing a book manuscript based on her dissertation, titled Postcolonial Trauma in South Asia: Body, Memory, and Displacement in Literature. One chapter has already been published in the edited collection The Postcolonial World, and another is to be published in the forthcoming Beyond Partition: Mediascapes and Literature in Post-colonial India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Rituparna is also working on a second book project that examines representations of global terrorism in South Asian Anglophone literature, where terrorism is linked to the failures of the postcolonial state and to uneven globalization.

Rituparna finds great inspiration in the peace and natural beauty of Marlboro, having spent most of her adult life in more urban areas. “Just being in a place that’s this beautiful, even when it’s gray and rainy, nurtures me in a sense. It feels magical, and nourishes creativity. I love that. So, on one hand, just the place— the physicality—but also the people I interact with. It’s such a joy to have intelligent, open-minded, aware people. I’m actually getting spoiled.”

William Ransom: Engaging with Materials

“Sculpture is often used as an umbrella term encompassing everything from carving stone or modeling clay to performance and video work—all of those things that exist beyond two-dimensional art,” says William Ransom, who joined Marlboro to teach sculpture and visual arts in the fall. “For myself, I have taught things that reach across that spectrum, all the way from direct material engagement to more installation-based stuff.”

“Sculpture is often used as an umbrella term encompassing everything from carving stone or modeling clay to performance and video work—all of those things that exist beyond two-dimensional art,” says William Ransom, who joined Marlboro to teach sculpture and visual arts in the fall. “For myself, I have taught things that reach across that spectrum, all the way from direct material engagement to more installation-based stuff.”

William was already familiar with Marlboro from years ago, when he was a Bennington College student and came to campus to play their perennial soccer rival. He also grew up in Strafford, Vermont, so after ten years on the West Coast, getting his MFA from Claremont Graduate University and teaching at Pomona College, Cal State San Bernardino, and California Institute of the Arts, he was eager to return to the Green Mountain State. A yearlong visiting professorship at Middlebury College only whet his appetite.

“Having grown up in Vermont, and now having kids, I started kind of stalking Marlboro College—in the best way—looking for job postings,” says William. “And when I saw the posting and dug a little bit deeper into the program, I was really smitten with the idea. The small size appeals to me because I like having a developed relationship with my students surrounding their work. That’s really valuable, and at bigger schools it’s hard to come by.”

William also likes the ability to plan his own curriculum and the potential for cross-pollination with other faculty members with overlapping interests. “One of the benefits about being in a small place is that nimbleness.”

When introducing students to sculpture, William starts from an embodied experience of material, asserting that there is a lot of useful information to be gleaned from paying attention to materials and direct material engagement with one’s hands and body. He often likes to start with clay because it is so receptive to manipulation in a way that wood or stone is not.

“Clay is immediately reflective of your engagement with it, and that immediacy gives feedback in the form of knowledge built into your body, if you are paying attention. I feel like students respond very well to the directness of that, as a point of entry. As you get further up on the ladder of learning about sculpture, the direct engagement leads to conceptual engagement, and materials run the spectrum from stone carving to installation, social sculpture, and performance-based work. I feel like material engagement is the way to open the door to those other more conceptually driven works and interacting with the audience—the caliber of student work is improved greatly by a broader material understanding.”

William’s own work often concerns issues of race and social justice, as well as sustainability, interaction with the natural world, and agricultural experience. He works with wood a lot, often testing its material potential in ephemeral installations that evoke dynamic tension between elements and invite audience participation.

“I really like the potential of the visceral encounter for the viewer,” says William, who has exhibited his work in galleries across the country, from New York, Detroit, and Chicago to California. Most recently, he was included in group exhibitions in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California, and a solo exhibition titled Hem n’ Haw, in Hudson, New York. William was awarded a Windgate Fellowship at Vermont Studio Center in 2015, in addition to several other fellowships over the years.

William is excited about a class he’s teaching this spring close to his own interests, called Art’s Ghost: The Ephemeral and Letting Go. In addition to exploring the rise of ephemerality in contemporary art history, students will be exploring materials that, by design, don’t last— from snow and ice to installation and performance art.

“We’ll be thinking pretty broadly about what it means to make something that has a brief window of time in which it can be experienced or enjoyed, and questioning the preciousness of objects,” says William.

A self-described biracial farm-boy, William recognizes that there are some drawbacks to relocating from southern California to Vermont, notably the relative scarcity of cultural institutions and opportunities and the lack of racial diversity. But he is certain that Marlboro’s geographic location should not hinder students’ access to culture. “I have been pleasantly surprised, actually, at how much more diverse Vermont has become since I was a kid here.”

Library Rocks NEH Grants

The Rice-Aron Library was the proud recipient of two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) this year. Together, they stand to increase the library’s impact within the local community and make its valuable archives more accessible.

The first was a joint NEH and American Library Association grant to take part in the Great Stories Club, a program that supports reading and discussion programs for underserved teens. Partnering with the Boys and Girls Club of Brattleboro, Rice-Aron Library was one of 100 libraries in the US selected for this grant, one of only five college libraries, and the only grantee chosen in Vermont.

“We are excited to start our book club in January, with the theme ‘What Makes a Hero: Self, Society, and Rising to the Occasion,’” says library director Beth Ruane. “The books include an amazing range of perspectives, from Black Panther to Art Spiegelman’s Maus II, chosen to inspire teens to consider big questions about the world and their place in it.”

The second NEH award is a Preservation Assistance Grant, designed to help small institutions improve their ability to preserve and care for significant humanities collections. The Rice-Aron archives are one such collection, composed of printed materials on paper, images, audio and video tapes, and historical ephemera stretching back to the founding of the college.

“Marlboro’s first students, most of whom were veterans, indelibly shaped Marlboro’s uniquely self-directed, self-governed, and self-reliant identity,” says Beth. “These primary source materials have great value to scholars and students studying in a wide range of areas, including the history of higher education in America, the post-WWII era, and the veteran experience.”

Rice-Aron’s archives were the subject of last year’s course titled History of Universities and the Liberal Arts, which focused on the history of Marlboro and its place in wider debates about the role and purpose of higher education. Students spent every other Thursday working in the archives to create more-specific subject categories for ease of finding, and shared some rare discoveries with the community through social media.

“Unfortunately, Marlboro has never been in a position to have a full-time archivist on its staff,” says Beth. “As a result, though the collecting of materials created by students, faculty, and administrative and departmental staff has been enthusiastic, knowing exactly what is held in the archives, let alone locating an item in a timely fashion, is nearly impossible.”

The first step of an ambitious project to improve stewardship and increase internal and external access to the college archives, the NEH grant will enable Beth to take classes at Simmons College in the area of Special Collections and Archives. “This training will position me to be a more effective steward of the college’s archives, able to develop realistic and appropriate planning for the assessment, processing, and ongoing care of this important collection.”

Home Days Enliven Hill

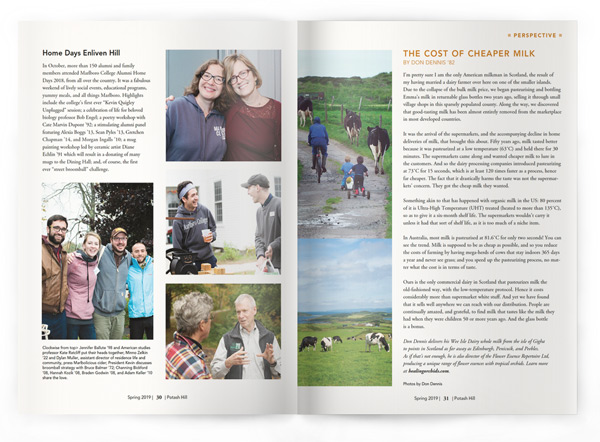

In October, more than 150 alumni and family members attended Marlboro College Alumni Home Days 2018, from all over the country. It was a fabulous weekend of lively social events, educational programs, yummy meals, and all things Marlboro. Highlights include the college’s first ever “Kevin Quigley Unplugged” session; a celebration of life for beloved biology professor Bob Engel; a poetry workshop with Cate Marvin Dupont ’92; a stimulating alumni panel featuring Alexia Boggs ’13, Sean Pyles ’13, Gretchen Chapman ’14, and Morgan Ingalls ’10; a mug painting workshop led by ceramic artist Diane Echlin ’91 which resulted in a donating of many mugs to the Dining Hall; and, of course, the first ever “street broomball” challenge.

Photos on left page above, clockwise from top> Jennifer Ballute ’98 and American studies professor Kate Ratcliff put their heads together; Minno Zelkin ’22 and Dylan Muller, assistant director of residence life and community, press Marlbolicious cider; President Kevin discusses broomball strategy with Bruce Balmer ’72; Channing Bickford ’08, Hannah Kozik ’08, Braden Godwin ’08, and Adam Keller ’10 share the love.

Events

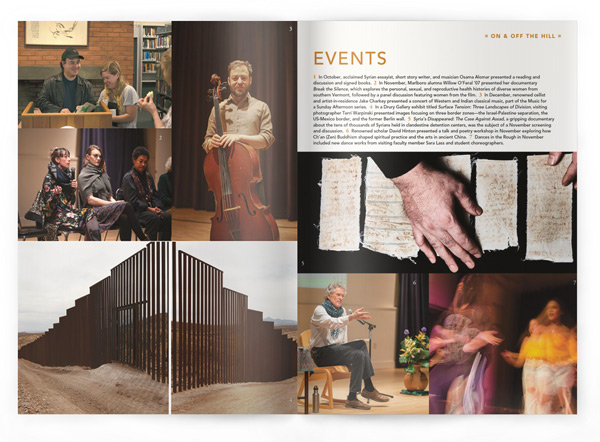

1 In October, acclaimed Syrian essayist, short story writer, and musician Osama Alomar presented a reading and discussion and signed books. 2 In November, Marlboro alumna Willow O’Feral ’07 presented her documentary Break the Silence, which explores the personal, sexual, and reproductive health histories of diverse women from southern Vermont, followed by a panel discussion featuring women from the film. 3 In December, renowned cellist and artist-in-residence Jake Charkey presented a concert of Western and Indian classical music, part of the Music for a Sunday Afternoon series. 4 In a Drury Gallery exhibit titled Surface Tension: Three Landscapes of Division, visiting photographer Terri Warpinski presented images focusing on three border zones—the Israel-Palestine separation, the US-Mexico border, and the former Berlin wall. 5 Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad, a gripping documentary about the tens of thousands of Syrians held in clandestine detention centers, was the subject of a November screening and discussion. 6 Renowned scholar David Hinton presented a talk and poetry workshop in November exploring how Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism shaped spiritual practice and the arts in ancient China. 7 Dances in the Rough in November included new dance works from visiting faculty member Sara Lass and student choreographers.

Focus on Faculty

Faculty Q&A

In December, Danielle Scobey ’22 sat down with American studies professor Kate Ratcliff to talk about oral history, aging, and radical decontextualization in America. You can read the whole interview at potash.marlboro.edu/ratcliff.

Danielle: How would you describe what you teach here?

Kate: My field is American studies, which is the interdisciplinary study of US history and culture. In general, my courses explore the connections between socio-historical forces and forms of cultural expression. Marlboro has been a wonderful place to do the kind of broad, integrative work that defines American studies. I feel incredibly lucky to have landed here 30 years ago, and it’s been an amazingly rich place to teach and grow as an academic.

D: What’s the best part about teaching at Marlboro?

K: Because our jobs are fairly broadly defined, we have space to develop new interests, which is such a luxury, and I think it contributes a lot of vitality to the institution. There really is the sense that students and faculty are continuously learning together and alongside one another.

D: What recent interests are you pursuing in classes?

K: One relatively recent area of interest is oral history. That’s just been so broadening for me. I love archival material, and there’s nothing like dusty documents to make my heart go pitter patter, yet I actually find it much more enjoyable to talk to people.

D: Why is it important to learn about history?

K: So much of history is about learning to see the world through the eyes of other people. I feel like the study of history is critical at this moment. We live in a culture that is ahistorical, and arguably hostile to history. Studying history helps cultivate empathy, nuance, complexity, and an appreciation for both continuity and change.

Photo by Emily Weatherill ’21

“Different religious traditions have answered basic questions about the same being in different ways and different historical circumstances,” says religion professor Amer Latif in a recent interview on BCTV. “Those answers take different shape, and yet because they are responding to the being that is constant, there is a similarity to them.” Speaking with Wendy O’Connell on Here We Are, Amer discusses growing up in Pakistan, morphing from a science student to a scholar of religion, and the many similarities he has found between Islamic and Christian texts. See the whole interview.

“Different religious traditions have answered basic questions about the same being in different ways and different historical circumstances,” says religion professor Amer Latif in a recent interview on BCTV. “Those answers take different shape, and yet because they are responding to the being that is constant, there is a similarity to them.” Speaking with Wendy O’Connell on Here We Are, Amer discusses growing up in Pakistan, morphing from a science student to a scholar of religion, and the many similarities he has found between Islamic and Christian texts. See the whole interview.

“By treating survivors as capable decision makers and requiring communities to clarify social norms, students who have been harmed by the sexual advances of others will have a much greater chance of healing and getting on with their education,” says politics professor Meg Mott. In a recent editorial in Inside Higher Ed, Meg argued that new Title IX guidelines benefit survivors as well as respondents, and that the rights of both parties are not mutually exclusive. See the article. In October, two days after the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh, Meg orchestrated a “Town Hall” on the Second Amendment at Moravian College, in eastern Pennsylvania. See Meg’s interview on BCTV’s Here We Are, where she speaks about the Commonplace Book, debate, and the need to hear more than one perspective.

Nelli Sargsyan, anthropology professor, had several scholarly works come out recently, including “Ֆեմինիստների և ֆեմինիստական գործելաոճերի` քաղաքական երևակայության ձևավորմանն ուղղված կարևոր գործը Հայաստանում” (The important work of feminists and feminist practices toward cultivating political imagination in Armenia) in the Armenian journal Սոցիոսկոպ (Socioscope). She also published an article in a special issue of History and Anthropology about activist politics in the post-socialist world, titled “Experience-Sharing as Feminist Praxis: Imagining a Future of Collective Care,” as well as an article in Queering Armenian Studies, a special issue of Armenian Review. Her chapter “On the Wings of Communal Bravery” appeared in Counternarratives from Women of Color Academics: Bravery, Vulnerability, and Resistance (Routledge 2018). In September, Nelli gave a talk in Brattleboro titled “The importance of feminist knowledge in political change: The case of the ‘Velvet Revolution’ in Armenia,” part of the Windham World Affairs Council speaker series.

Theater professor Brenda Foley returned from her two-year fellowship as the Carol L. Zicklin Endowed Chair at Brooklyn College this fall, only to share other exciting news: she is editing a new Routledge series focused on equity, diversity, and inclusion in theater and performance. “I’m honored that Routledge has asked me to be editor of this exciting new series, and look forward to encouraging and supporting the work of scholars and artists who have historically been underrepresented in theater and performance publishing,” says Brenda. Her own current book project, A Legacy of Violence: Women, Mental Illness, and Performance (under contract with Routledge), explores the violence inherited from our asylum history in contemporary cultural representation of women and mental illness. Learn more. Smith and Kraus has also selected a monologue from Brenda’s play Camouflage for inclusion in their anthology The Best Women’s Monologues of 2019.

“Brattleboro is one of three locations where we’re gathering Vermonters together,” says management faculty member Kerry Secrest, referring to a Vermont Commission on Women’s Listening Project event titled “The Hidden Side of Women’s Lives in Our Community.” The statewide Listening Project survey asks what needs aren’t being met for Vermont women, what most affects their abilities to provide for themselves or their families, and what can be done to help. “This is an opportunity for community members to shape the work of our commission,” says Kerry, one of the Brattleboro commissioners who hosted the event. “We want to listen to the real-world experiences of women in our community, their stories, and the challenges they encounter in their everyday lives.”

Photography professor John Willis presented an exhibit titled “Mni Wiconi: Honoring the Water Protectors” at Cynthia Reeves Contemporary Art Gallery, in North Adams, Massachusetts; Southeast Florida Community College; Green Mountain College; and Keene State College. In November, John was one of six Vermont artists honored by the Vermont Arts Council at a ceremony in Montpelier. John received the Ellen McCulloch-Lovell Award in Arts Education, named for Marlboro’s retired president. Learn more. But John is most animated about the purchase of a new 3,300-square-foot space in Brattleboro by In-Sight Photography Project, the youth arts program he co-founded. “We will move the program over and have a larger, safer, up to date, and fully accessible teaching space. Marlboro students have been teaching and volunteering there for 26 years and will continue. Yeah!”

Rituparna Mitra, Marlboro’s new professor of writing and literature, presented in two panels at the Modern Languages Association Annual Conference held in January in Chicago. She presented her paper titled “Postcolonial ecologies and embodied memory in Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide and Akhtaruzzaman Elias’s Khoabnama” on the panel on Textual Transactions in Bangladeshi/ Bengali Literature. Her paper titled “Precarious Duniyas: Posthuman subjectivity and politics in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” was featured on the panel on The Global South Novel. Also in January, Rituparna presented her paper titled “The ghazal and the gathering of worlds in Ali’s ‘The Country without a Post Office’” at the meeting of the South Asian Literary Association in Chicago.

Rosario DeSwanson, professor of Spanish language and literature and gender studies, presented her new book “¿Y cuál es mi lugar, señor, entre tus actos?”: El drama de Rosario Castellanos (Peter Lang, 2018) at Keene State University and Bennington College. “Although there are numerous studies that engage with the work of Mexican feminist Rosario Castellanos, most center on her narrative prose, poetry, or essays. My book addresses this vacuum, offering scholars a complete study of all of her plays while it traces her ideas regarding the place of female intellectuals within the nation, as her first drama coincides with her decision to become a writer.” The book received advanced praise from Velma Garcia, professor of government and Latin American and Latino studies from Smith College, and from Gene Bell-Villada, professor of romance languages at Williams College. See the book.

“It’s a place that resonates with these iconic images that are very fertile in the American imagination— the clearing in the woods and the hilltop setting,” says President Kevin Quigley, referring to Marlboro College in a September article in The Chronicle of Higher Education. “Both are rich metaphors for the establishment of a community, particularly a learning community.” The special report highlights Marlboro’s bucolic setting, sense of community, and the ability of students to effect change through shared governance. It also touches on the college’s recent struggles with enrollment and financial setbacks, shared by many other small colleges, but emphasizes the college’s many strengths being brought to bear on issues.

“It’s a place that resonates with these iconic images that are very fertile in the American imagination— the clearing in the woods and the hilltop setting,” says President Kevin Quigley, referring to Marlboro College in a September article in The Chronicle of Higher Education. “Both are rich metaphors for the establishment of a community, particularly a learning community.” The special report highlights Marlboro’s bucolic setting, sense of community, and the ability of students to effect change through shared governance. It also touches on the college’s recent struggles with enrollment and financial setbacks, shared by many other small colleges, but emphasizes the college’s many strengths being brought to bear on issues.

Ian McManus, Marlboro’s new professor of economics, had an article accepted for publication in the Journal of Common Market Studies. Titled “The reemergence of partisan effects on social spending in Europe after the global financial crisis,” the article analyzes how the politics of social spending changed after the Great Recession in Europe and other advanced welfare states. Ian is also working on a manuscript of his dissertation and other articles on the politics of social and economic policymaking across countries. “This work highlights vital issues, including the distributional effects of the Great Recession, the effects of international institutions on domestic policies, the influence of political parties and ideologies on social spending, and the negative effects of inequality on economic growth and social well-being,” he said.

Theater and gender studies professor Jean O'Hara published an article titled “Unsettling the Frontier Fable” in the September 2018 issue of Q2Q: Queer Canadian Theatre and Performance. In November, Jean and her colleague (and last May’s commencement speaker) Shaunna Oteka McCovey were awarded a grant from Theatre Communications Group, as part of its Global Connections program supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. “We will create a play adaptation of the book In the Land of the Grasshopper Song: Two Women in the Klamath River Indian Country in 1908-09,” says Jean. “Although the book is a historical account of early contact between the Karuk Nation and European-Americans, it is ultimately written from a white perspective. It is our intention to write it from a Karuk perspective that also includes the Karuk language.” Jean and Shaunna (who is Yurok and Karuk) will co-create the play while also organizing events that allow for Karuk Tribal member participation.

Bronwen Tate, professor of writing and literature, published a poem in the October issue of About Place Journal, which is on the theme of Roots and Resistance, titled “By Gift, Purchase, Capture, or Inheritance." She published a handful of poems in the tiny mag as well, and an essay called “‘The Narrative No Longer Just Contains It Involves’: Frank Stanford’s Collective Visions” in the anthology Constant Stranger: After Frank Stanford. “I also gave poetry readings and talks at the Frank Stanford Literary Festival in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and the Stanford University DARE@10 Homecoming in Palo Alto, California,” says Bronwen.

Philosophy and environmental studies professor William Edelglass has several pieces forthcoming, including “The Ethics of Difference and Singularity: Levinas, Responsibility, and Climate Change,” in Moral Theory and Climate Change: Ethical Perspectives on a Warming Planet, edited by Dale E. Miller and Ben Eggleston, Routledge, 2019; and “Aspiration, Conviction, and Serene Joy: Faith and Reason in Indian Buddhist Literature on the Path,” forthcoming in Beyond Faith Versus Reason: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Philosophy of Religion, edited by Sonia Sikka and Ashwani Peetush. William was a guest on a recent episode of the Imperfect Buddha Podcast, and in September his work was profiled in an interview with Richard Marshall in 3:AM Magazine (see an excerpt in this Potash Hill).

Also of Note

“Community service forms a very important part of life at Marlboro, and I’m very glad to be a part of it this year,” said Lamia Barakat, Marlboro’s Fulbright Arabic language fellow (pictured with sophomore Alyssa Strobele). She was invited to share her perspective on community service at Marlboro at a Fulbright conference in Washington, DC, in December. In a video presented at the conference, Lamia describes painting a local ski hut, gardening on campus, doing trail work, and maintaining the climbing wall alongside students and other community members. She also interviews President Kevin, who shares his perspective on the history of community service at Marlboro. Learn more.

“Community service forms a very important part of life at Marlboro, and I’m very glad to be a part of it this year,” said Lamia Barakat, Marlboro’s Fulbright Arabic language fellow (pictured with sophomore Alyssa Strobele). She was invited to share her perspective on community service at Marlboro at a Fulbright conference in Washington, DC, in December. In a video presented at the conference, Lamia describes painting a local ski hut, gardening on campus, doing trail work, and maintaining the climbing wall alongside students and other community members. She also interviews President Kevin, who shares his perspective on the history of community service at Marlboro. Learn more.

Surprisingly, in October Marlboro College was mentioned in the U.S. News & World Report’s list of the 10 colleges with the most undergraduates. “The University of Central Florida tops the list with nearly 57,000...more than 300 times the enrollment at the ranked school with the fewest undergraduates: Marlboro College in Vermont, which only had 183 students.” What they fail to mention is that Marlboro’s faculty-student ratio is 5:1, as opposed to UCF’s 30:1, or that there are more than two acres per student at Marlboro while UCF students get a mere 1,300 square feet. Do they have a cookie drawer, or a wood-fired sauna?

During the fall, juniors Menefese Kudumu-Clavell, Ricarrdo Valentine, and Nicktae Marroquin-Haslett were all on a semester exchange at Marlboro’s newest international partner school, Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí, in México. “I feel like I’ve expanded as an artist, as a result of my time there,” said Ricarrdo, who is working on a Plan in dance and photography focusing on Afro-Mexican identity and dance. “I was able to explore other cross-collaborative media, and try new ideas.” Ricarrdo also had the opportunity to set up an internship for next fall in Veracruz, creating dance with youth and collaborating with an anthropologist there, a connection made through anthropology professor Nelli Sargsyan.

“Studying abroad isn’t always about making your imagination into reality; sometimes it’s about going deeper into the experience that’s already in front of you,” says junior Alta Millar. Alta spent the fall semester at the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, located in southeast London, studying contemporary dance and choreography. “What was so exciting for me was that my dancers knew exactly what I wanted. I was using Laban notation terminology to describe the movement. With this shared language, they were able to pick it up instantly and visualize my ideas in real time.” See Alta’s blog posts.

Longtime financial aid director Cathy Fuller was appointed to the position of registrar in July, capping more than 19 years of working at Marlboro, having started out in student accounts for almost five years, then in financial aid for 14. “My favorite part of being registrar is celebrating successes with students, whether it’s graduating, meeting a deadline they didn’t think they could meet, or hearing about courses they are so excited about.” She also likes working more closely with faculty, but misses her colleague Jayne Rivers, who she worked with for many years. “The other thing I miss is the federal guidelines—call me crazy but I liked the legal aspect of them.”

“Marlboro has worked hard over the years to ensure that we have dealt with Title IX cases fairly, thoroughly, and with respect to our shared community values of safety, learning, and inclusiveness,” said President Kevin in a December letter to the community. The letter was in response to new Title IX regulations proposed by the U.S. Department of Education that would require significant changes in how Marlboro addresses claims of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and other rights violations. While the new regulations have yet to be made law, the letter shares the college’s initial reactions and plans for addressing the proposed regulations. Read the letter.

River Run  On the morning of August 26, the inaugural New England Green River Marathon started at Marlboro College—an auspicious start for the academic year. “Getting the most out of your college years is a marathon in a very real sense, and it seemed fitting for Marlboro to sponsor and host the beginning of this pioneering race,” said President Kevin. Learn more.

On the morning of August 26, the inaugural New England Green River Marathon started at Marlboro College—an auspicious start for the academic year. “Getting the most out of your college years is a marathon in a very real sense, and it seemed fitting for Marlboro to sponsor and host the beginning of this pioneering race,” said President Kevin. Learn more.

Source to Sea  In September, several students joined chemistry professor Todd Smith for the Connecticut River Conservancy’s Source to Sea Cleanup, part of the 2,853 volunteers who removed 46 tons of trash from 174 miles of the river.

In September, several students joined chemistry professor Todd Smith for the Connecticut River Conservancy’s Source to Sea Cleanup, part of the 2,853 volunteers who removed 46 tons of trash from 174 miles of the river.

Quill to Live  Found lying by a road on campus last September, this porcupine was treated for two weeks by nearby wildlife rehabilitator Patti Smith. “She was returned to the college and is doing just fine, eating raspberry leaves, that is, not taking exams,” says Patti, a naturalist at Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center. Photo by Patti Smith

Found lying by a road on campus last September, this porcupine was treated for two weeks by nearby wildlife rehabilitator Patti Smith. “She was returned to the college and is doing just fine, eating raspberry leaves, that is, not taking exams,” says Patti, a naturalist at Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center. Photo by Patti Smith

Think Ice  The Outdoor Program moved the location for the skating rink from the soccer field to a more central location in the meadow below the Campus Center, with the help of Hannah Anderson, coordinator for student activities and recreation, and senior Daniel Madeiros.

The Outdoor Program moved the location for the skating rink from the soccer field to a more central location in the meadow below the Campus Center, with the help of Hannah Anderson, coordinator for student activities and recreation, and senior Daniel Madeiros.

Clear Writing Fuel  First year student Emmanuel Miller considers her options during Midnight Breakfast, the traditional festive meal on the night before writing portfolios are due.

First year student Emmanuel Miller considers her options during Midnight Breakfast, the traditional festive meal on the night before writing portfolios are due.