Fall 2019

Editor’s Note

While this issue of Potash Hill was in production, Marlboro announced an ambitious plan to merge with the much larger University of Bridgeport. I call it ambitious because it was not the easy way out—that would have been going fizzle, spending down the college’s endowment until its only assets were a cluster of buildings on a quiet hilltop. Instead, a task force of community members who care deeply about Marlboro found the best strategic partner they could, hopefully providing an influx of diverse students while protecting the college’s student-focused pedagogy and faculty-governed curriculum.

While this issue of Potash Hill was in production, Marlboro announced an ambitious plan to merge with the much larger University of Bridgeport. I call it ambitious because it was not the easy way out—that would have been going fizzle, spending down the college’s endowment until its only assets were a cluster of buildings on a quiet hilltop. Instead, a task force of community members who care deeply about Marlboro found the best strategic partner they could, hopefully providing an influx of diverse students while protecting the college’s student-focused pedagogy and faculty-governed curriculum.

As we all await details of the proposed merger in the coming months, this Potash Hill finds much to celebrate, per usual. From Marlboro’s sparkly new website to the college’s designation as an Ashoka U Changemaker Campus, from the new Data Humanist certificate to the student-led trip to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, this issue is bursting with good news. While the features are on the darker side, focusing on the life-and-death struggle of refugees and the role of ghostly folklore on the Marlboro campus, they still celebrate the diverse and important pursuits—and clear writing—of students and alumni.

As always, Potash Hill applauds the entrepreneurial spirit of Marlboro alumni, from fashion visionary Raghavendra Rathore ’91 in India and coffee prophet Dagmawi Iyasu ’98 in Ethiopia all the way home to Brattleboro’s arts innovator Teta Hilsdon ’87. We will greatly miss collaborating with extraordinary photographer, musician, and holistic education guru Clayton Clemetson ’19, and eagerly anticipate what lies ahead for him. Once again (even if you’ve signed up before), we urge you to let us know what lies ahead for you by signing up on the new, improved Branch Out, Marlboro’s own online community for connecting, engaging, and supporting.

Where is your own entrepreneurial niche, or what was your favorite ghostly anecdote from Howland? As always, we love to hear from our readers at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

—Philip Johansson

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Photo Editor: Richard Smith

Staff Photographers: Clayton Clemetson ’19, David Teter ’20, and Emily Weatherill ’21

Communications Director: Carla Snook

Alumni Director: Maia Segura ’91

Design: Falyn Arakelian

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Potash Hill is available online at Marlboro College’s website: www.marlboro.edu.

Front Cover: Marlboro students face the admissions building and the sweeping horizon beyond.

About Marlboro College  Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests while developing transferrable skills that can be directly correlated with success after graduation, known as the Marlboro Promise. These skills are: (1) the ability to write with clarity and precision; (2) the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals; and (3) the ability to lead an ambitious project from idea to execution. Marlboro students fulfill this promise in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests while developing transferrable skills that can be directly correlated with success after graduation, known as the Marlboro Promise. These skills are: (1) the ability to write with clarity and precision; (2) the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals; and (3) the ability to lead an ambitious project from idea to execution. Marlboro students fulfill this promise in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

“It’s an experience that will change you,” says Grace Hamilton ’20 (above right), who was one of the students featured in a recent video titled “What you should know about Marlboro College.” Find out what you should know.

Up Front

Thresholds of Geography

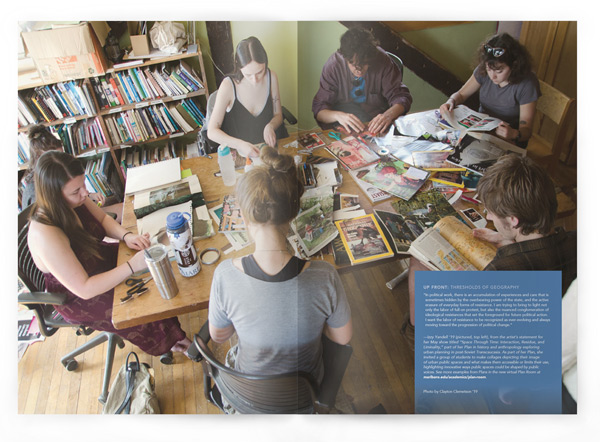

“In political work, there is an accumulation of experiences and care that is sometimes hidden by the overbearing power of the state, and the active erasure of everyday forms of resistance. I am trying to bring to light not only the labor of full-on protest, but also the nuanced conglomeration of ideological resistances that set the foreground for future political action. I want the labor of resistance to be recognized as ever-evolving and always moving toward the progression of political change.”

—Izzy Yandell ’19 (pictured, top left), from the artist’s statement for her May show titled “Space Through Time: Interaction, Residue, and Liminality,” part of her Plan in history and anthropology exploring urban planning in post-Soviet Transcaucasia. As part of her Plan, she invited a group of students to make collages depicting their image of urban public spaces and what makes them accessible or limits their use, highlighting innovative ways public spaces could be shaped by public voices. See more examples from Plans in the new virtual Plan Room.

Photo by Clayton Clemetson ’19

Clear Writing

Claims: The Gathering

by Tristan Rolfe ’18

While struggling to instill some semblance of structure in a messy draft, I developed my own style of outline, which several of my tutees have found useful. Ideally, it refines disorganized papers with a dragnet of claims woven from the work itself. The ultimate goal of the exercise is to allow the writer to build their own image of their paper’s architecture through claims.

My inspiration for the exercise came from my style of deck building in Magic: The Gathering, a card game I’ve played since childhood. I’ve always loved the game for its emphasis on the synergy of the cards rather than their individual strengths, and built every deck by sorting cards into piles based on their desired effects upon my opponents. By examining each pile and the cards within as both a piece of the whole and a set by itself, I gained a clear image of the deck as it was versus the deck I wanted. The same juxtaposition applies to writing through this exercise, because analytical writing hinges on the same synergy—between claims.

The first step in this type of outline is to review the existing work and highlight claims. Next, the information required to support each claim should be written beneath each claim—if the writer doesn’t know the information yet, that’s fine. This step will show them what they need to research and what they understand. It’s worth writing the claims and information in different colors. The writer’s argument should be written too, as the ultimate claim.

Then, assign claims to sections. Every paper will have an introductory section, during which the ultimate claim should be established, and a conclusion that refers back to it. Other claims will fill up the body sections, and assigning them in this outline can show the writer where their paper needs development.

Then, assign claims to sections. Every paper will have an introductory section, during which the ultimate claim should be established, and a conclusion that refers back to it. Other claims will fill up the body sections, and assigning them in this outline can show the writer where their paper needs development.

Once you have this larger architecture, you’ll develop it by outlining each section. I have a specific system I use for noting what I call “chunks” in each section. With the entire paper sorted into these chunks, the author can rearrange them in sections as I would cards to evaluate their work’s relationship to product through an overview of their process.

Tristan Rolfe graduated in December 2018 with a Plan in literature and writing and the teaching of both. This article is excerpted and adapted from his piece titled “Ambitions as a Writer,” based on his experiences tutoring in the Writer’s Block at Marlboro College.

Letters

Marlboro Memories Just thumbing my way through the Spring 2018 Potash HillI feel so proud of the Marlboro community and what it has accomplished in its young life. I have a lot of incredibly good memories, and I think a number of alumni do too, but so few of us write back or celebrate them. What is it about the ’60s? Maybe I can stir something up with these notes from 1963–67.

Just thumbing my way through the Spring 2018 Potash HillI feel so proud of the Marlboro community and what it has accomplished in its young life. I have a lot of incredibly good memories, and I think a number of alumni do too, but so few of us write back or celebrate them. What is it about the ’60s? Maybe I can stir something up with these notes from 1963–67.

Town Meetings were successful: we passed the dog/cat ruling—no pets on campus except Fangio and Tippy; parietal hours were agreed upon—if you are going to do it, be respectful of your room mate; no smoking in the dining hall.

Other memories: dance weekends— we had one even with the recent death of JFK; Pink God Dammit parties to celebrate spring; motorcycles on the iced fire pond; the poker and bridge games that seem to go on all week; homemade beer that exploded in one of the dormitories along with the pen of rabbits in a nearby room; Thanksgiving dinner with the Boydens; the first Wendell Cup ski race.

Marlboro College taught me a lot and I have used these lessons well in my life. Be accountable, be responsible to your community. Give back as much as you have taken, or give more. Enjoy life to the fullest.

—Jennie Tucker ’67

PotashLove What a beautiful and stirring issue of Potash Hill (Spring 2018). I was especially glad to read about Marlboro’s new faculty, who sound as though they quickly absorbed the spirit and promise of this unique place and education. Congratulations on such a good, informative, and aesthetically pleasing issue!

What a beautiful and stirring issue of Potash Hill (Spring 2018). I was especially glad to read about Marlboro’s new faculty, who sound as though they quickly absorbed the spirit and promise of this unique place and education. Congratulations on such a good, informative, and aesthetically pleasing issue!

—Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, former president

Another great issue! It’s everything a magazine like this should be: plenty of substantive, well-written articles, great photos, focus on the people of the college and issues of interest to them. Congratulations.

—Dick Saudek, chair of the board of trustees

I so look forward to each issue of Potash Hilland other mailings from Marlboro. Thanks for another high-quality and informative issue. Although I canceled all magazines, catalogs, and newspapers to save on waste, I can’t bear to not have a printed copy of such a beautiful and meaningful publication.

—Diana Piper, parent of Marty Piper ’20

Climate of Change

Thank you for your note on the climate, and asking for more reflection from alumni. On our Leafhopper Farm (leafhopperfarm. com) in western Washington, we’ve just put in a 20,000-gallon cistern on the property—a temperate rainforest. Also, summer fires are getting redundant. Smoke was the worst in 2018. With record-breaking temperatures of 790F in Seattle in the last two days of winter, I’m sure we’ll be in for another above-normal summer this year too. For someone paying close attention to food security and global environmental failure, I worry we’re seeing a crash. Not only have we forgotten our seat belt, humanity insanely scrambles to slash the airbags.

—Liz Crain ’05

Claim to Fame

I’m a biologist, with a longtime interest in the history of modeling in ecology and population biology. I ran across Dan Toomey’s nice article on Robert MacArthur ’51 in the Summer 2013 issue of Potash Hill. Are you folks aware of the “legendary” meeting that occurred in 1964 (or so) in Marlboro? E. O. Wilson’s account of it in Naturalist has some details: attendees were himself, Richard Levins, Dick Lewontin, Robert MacArthur, and Egbert Leigh, and by Wilson’s account this meeting helped initiate much important research in population biology. So, Marlboro has a claim for playing an important role in the history of ecology.

—Steve Orzack

Empty Promise?

In the last issue of Potash Hill, President Kevin’s message was about the promise of Marlboro to have graduates able to write clearly, follow a big idea to completion, and live in a community. Some students do not know what it is to live in a community, as they are ostracized in a social climate that includes bullying and toxicity. My hope is that rather than “live in a community,” Marlboro instead focuses on creating true community as part of its future growth.

—anonymous parent

View from the Hill

Planned Merger Stands to Help Marlboro Weather Storm

By President Kevin F. F. Quigley

In these pages last fall, I wrote about the often-cited Chinese curse: “may you live in interesting times.” Since then, the closure of a number of small liberal arts colleges in Vermont—Green Mountain College, Southern Vermont College, and the College of Saint Joseph—suggests sadly that the curse rings true. By now, many of you will have heard that Marlboro has chosen a different and very exciting course of action: a merger with University of Bridgeport (UB).

Although Marlboro faces similar challenges as other colleges in New England—with its rapidly changing demographics—we are privileged to also have assets and strengths that our less fortunate neighbors don’t have. Thanks to our amazingly generous supporters we have a large endowment on a per-student basis, and we hold very modest debt, providing some “runway” to address our circumstances and devise a plan for the future. Like all colleges confronting these challenges, Marlboro had essentially three options: (1) go it alone, (2) close, or (3) find a strategic partner.

To carefully consider these options, last November the board of trustees established a Strategic Options Task Force, which soon determined that option (3) was the only sustainable course of action. This task force has been guided by two overarching principles important to our community: participation and transparency. The group included five trustees, three faculty members, and a student. While protecting the necessary confidentiality of potential institutional partners, we provided regular updates to the community at weekly Town Meeting, as well as at regular faculty and staff meetings.

To help navigate the Scylla and Charybdis of the partnership processes, we selected a well-respected consulting firm, EY-Parthenon (EYP), and began working with them in January 2019. EYP led a process where our community defined Marlboro’s most important attributes and assets and what we ideally would like to find in a partner, interviewing task force members and conducting six focus groups with students, faculty, and staff. Not surprisingly, the community identified assets and attributes revolving around Marlboro’s purpose, people, and place.

With EYP’s assistance, Marlboro reached out to some 70 institutions that met our criteria, including unmet demand for enrollment and higher net tuition per student. From this group of colleges and universities, nearly two dozen conversations and eventually four very strong partnership proposals emerged. In considering these proposals, the task force conducted extensive due diligence involving multiple site visits, lengthy discussions about vision and institutional priorities, and review of financial and enrollment data.

At a June meeting, the task force recommended to the trustees that we move ahead in exploring a partnership with UB, the one institution that saw real value in our mission and our campus. This was agreed to unanimously by the trustees, and signed by both parties in late July. In addition to an enormously evident complementarity between our missions, locations, and personnel, of all the potential partners UB was most committed to preserving our purpose, people, and place.

While there is more work to be done, we hope in the next few months to finalize a partnership agreement that will provide a much more sustainable future for Marlboro’s educational mission and values at a time of significant change for small liberal arts colleges. We will keep the community informed as we move ahead on our exciting new path.

While this issue of Potash Hill was in the mail, on August 13, negotiations for this merger were called off. For the latest information about the partnership process, go to our website.

The Eternal Presence of Absence

By Lauren Beigel MacArthur ‘02

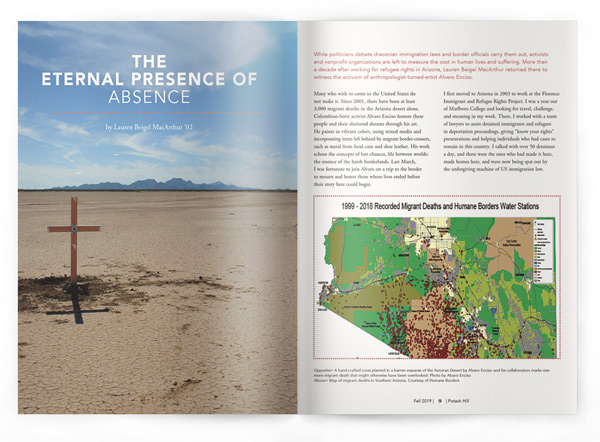

While politicians debate draconian immigration laws and border officials carry them out, activists and nonprofit organizations are left to measure the cost in human lives and suffering. More than a decade after working for refugee rights in Arizona, Lauren Beigel MacArthur returned there to witness the activism of anthropologist-turned-artist Alvaro Enciso.

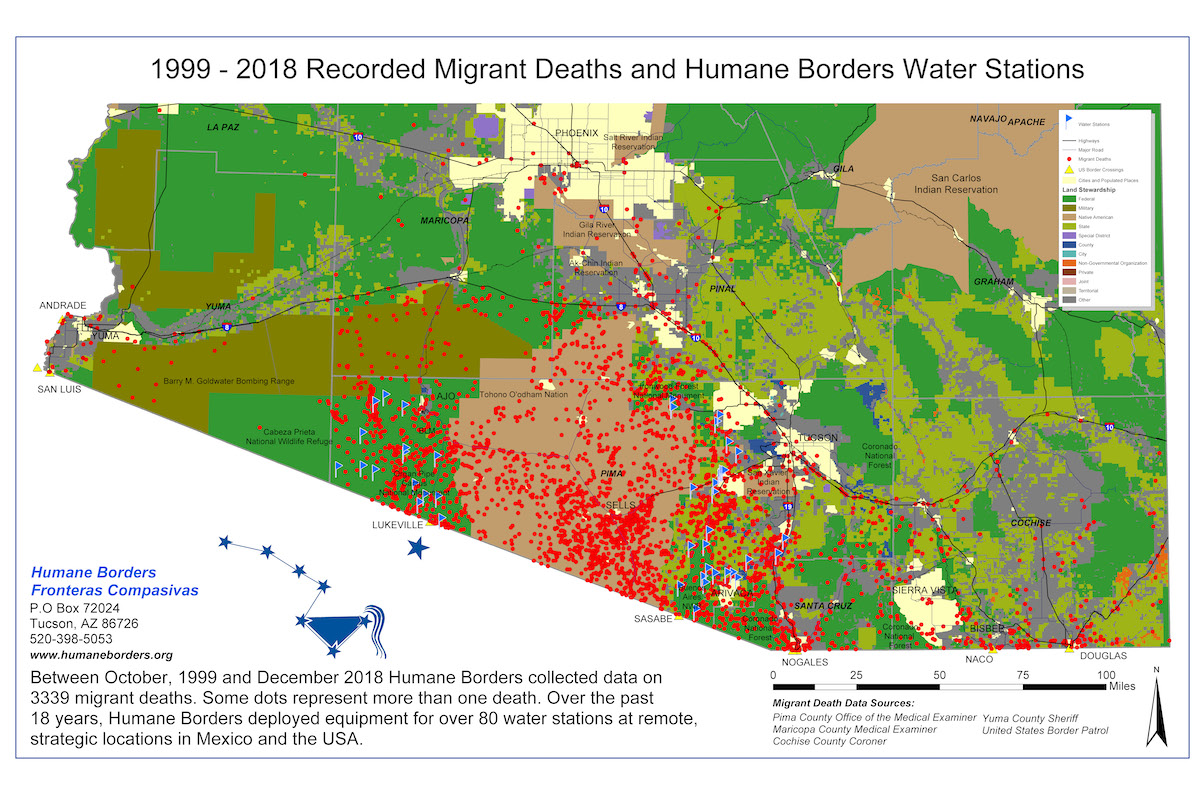

Many who wish to come to the United States do not make it. Since 2001, there have been at least 3,000 migrant deaths in the Arizona desert alone. Colombian-born activist Alvaro Enciso honors these people and their shattered dreams through his art. He paints in vibrant colors, using mixed media and incorporating items left behind by migrant border-crossers, such as metal from food cans and shoe leather. His work echoes the concepts of lost chances, life between worlds: the essence of the harsh borderlands. Last March, I was fortunate to join Alvaro on a trip to the border to mourn and honor those whose lives ended before their story here could begin.

I first moved to Arizona in 2003 to work at the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. I was a year out of Marlboro College and looking for travel, challenge, and meaning in my work. There, I worked with a team of lawyers to assist detained immigrants and refugees in deportation proceedings, giving “know your rights” presentations and helping individuals who had cases to remain in this country. I talked with over 50 detainees a day, and these were the ones who had made it here, made homes here, and were now being spat out by the unforgiving machine of US immigration law.

In my work I heard many, many stories about border crossings—walks through deserts, dangerous drives, weeks in shipping containers, losing family members, money, and possessions along the way. After two years, my heart and soul were battered, exhausted, and longing to return to Vermont. I did come home to these Green Mountains, but lodged in my heart was that state, that border, and that crisis—those individual lives so devastated by our country’s inhumane immigration policies. After more than a decade, I have begun to revisit Arizona, and this spring I was able to return to the border with Alvaro.

lvaro has created his own “red dot” project, entitled Donde Mueren los Sueños (where dreams die), in which he places hand-crafted wooden crosses on the exact sites of migrant deaths. Using information provided by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, he hikes out into the desert with small groups of helpers to find the “red dots” on the map and pay tribute. This project has recently gained national recognition as the border has become a kind of war zone and political focal point.

lvaro has created his own “red dot” project, entitled Donde Mueren los Sueños (where dreams die), in which he places hand-crafted wooden crosses on the exact sites of migrant deaths. Using information provided by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, he hikes out into the desert with small groups of helpers to find the “red dots” on the map and pay tribute. This project has recently gained national recognition as the border has become a kind of war zone and political focal point.

Donde Mueren los Sueños began as an effort to honor the deceased migrants, and has turned into an action that is drawing new awareness to what has been happening on the border for quite some time. Recent border walls and immigration policies have pushed desperate border crossers into harsher and more dangerous territory, where there is little water and temperatures are well above 100 degrees for many months of the year. Alvaro has placed over 900 crosses, and shows no signs of slowing down.

“No one in Vermont was thinking about the border, and the people who are dying here,” said Alvaro. “No one in Ohio was thinking about it either. But then suddenly the newspaper is mentioning this crazy old guy putting crosses up in the desert, and it catches their attention, and then I hope they’ll begin to think about it.”

While visiting Arizona in March with my family, I had the opportunity to join Alvaro on one of his weekly trips to the border. With Alvaro at the wheel of a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle, I sat wedged between two members of the Tucson Samaritans group, locals who care deeply about the plight of migrant border-crossers. These activists spend their weekends hiking remote canyons and leaving gallons of water and other supplies for migrants who might come that way, something for which they now risk criminal charges.

As we drove south from Tucson toward the small border town of Arivaca, the Samaritans told me about their weekly meetings with a large group of concerned Tucsonians, and how they volunteer at shelters for asylum seekers. They talked about joining protests and civil disobedience actions in places like Arivaca, a town suddenly overrun with US Border Patrols, “militias,” and the harsh reality that current immigration policies have written a death sentence for so many desperate people. Now funneled through this desert corridor and channeled through drug traffickers’ mafia-like hierarchy, migrants face an incredibly perilous journey if they decide to travel overland from Mexico to the United States.

We picked up our navigator in Arivaca, a sturdy young woman who clutched the GPS to her chest and led us to the exact point where skeletal remains had been found in the early 2000s. We drove out rough dirt roads winding through grassy knolls dotted with mesquite, rising in and out of dry, rocky washes. Our navigator pointed out a place she’d tried to camp recently with some friends.

We picked up our navigator in Arivaca, a sturdy young woman who clutched the GPS to her chest and led us to the exact point where skeletal remains had been found in the early 2000s. We drove out rough dirt roads winding through grassy knolls dotted with mesquite, rising in and out of dry, rocky washes. Our navigator pointed out a place she’d tried to camp recently with some friends.

“The Border Patrol kept driving by, slowing down to look at us every time they went by,” she said. “We finally got sick of it and just packed up our campsite and left.” I realized that she could be mistaken for a Mexican, with her dark hair and indigenous-looking cheekbones.

We parked at a cattle corral and walked over a ridge into rustling grass, with an eye out for rattlesnakes. The powerful Arizona sun pressed down upon our backs, and our small group stopped to wipe off sweat, drink from our full water bottles, and have a snack before continuing on. We were eight miles from the border when we reached the site of the red dot, in lovely, rolling hills with views of distant mountains. We set to work digging a hole, placing the salmon-colored cross, pouring in some quick-dry concrete and water, and placing rocks around the base of the cross. We stood for a while in silence. There was no information about this deceased person. No name or cause of death.

I imagined what it would be like to die here. Did this person know that just over the ridge was a dirt road that could be followed to the highway? Were they alone here? Did their family ever find out what happened to them? Alvaro spoke of the “eternal presence of absence”: how this person still occupies an empty chair at the holidays, still represents a question mark in his or her family’s mind. Their family is probably still wondering if someday the phone will ring or they will hear footsteps at their door. “Each of these deaths is a tragedy, and ripples out into others’ lives,” Alvaro said.

We left the lonely cross and three gallons of water (“hidden” in some shrubs), and set off in our vehicle down a rough rancher’s track into the hills. There was a border patrol tower perched on top of one of the higher knolls, and I thought of how unsettling it would be to walk through these hills, knowing that so many eyes could be watching. We could see on the GPS map that another site Alvaro had already marked was not far off this rough road, and finally parked by a small stream. We followed our navigator up a steep slope to the backside of a small tree, a branch looming above us.

A young man named Isidro Revollar-Herrera had died here, taking his own life. It was painful to imagine what he must have been experiencing to drive him to this fate. Alvaro explained the kind of pain that a slow death by heat and dehydration could inflict, and how seeking relief in hanging oneself with a belt or shirt was not a quick escape either. From Isidro’s last view, we could see the dirt track winding out of sight.

A young man named Isidro Revollar-Herrera had died here, taking his own life. It was painful to imagine what he must have been experiencing to drive him to this fate. Alvaro explained the kind of pain that a slow death by heat and dehydration could inflict, and how seeking relief in hanging oneself with a belt or shirt was not a quick escape either. From Isidro’s last view, we could see the dirt track winding out of sight.

I hope to continue to return to the desert to hike the canyons and enjoy its surreal beauty, but my privilege to do so is never far from my mind. I think of the ridiculous “reality” television shows that glorify “survivors” or those who struggle through obstacle courses to get to an arbitrary finish line. In actual reality, the migrant men, women, and children who navigate the most dangerous route imaginable into our country deserve just as much recognition: for the physical feat and the emotional steeliness they need to embody. They deserve to collapse at the finish line into our arms, to be fed, housed, clothed, and awarded compassion. But even if they make it here, their race has only begun. And if they do not, a humble artist will mark the story of their lives with a painted wooden cross.

Lauren Beigel MacArthur completed her Plan in environmental studies, with a focus on tropical agroecology and Latin American literature, in 2002. She received an MEd at Antioch New England and taught middle school humanities for five years before having two children and running Whetstone CiderWorks with her husband. She currently lives a patchwork Vermont life in Marlboro as a farmer, child advocate, cook, and creative writing teacher, among many other things. For further reading she recommends The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, by Francisco Cantú, and The Devil’s Highway, by Luis Alberto Urrea. For more information about Alvaro Enciso and his work, visit facebook.com/alvaro.enciso.5.

Legislating Refugees  “Trade laws and work programs passed by the United States in nearby Puerto Rico and Mexico have weakened the economies of these already struggling countries for many years,” says Emmett Wood ’19. In a Plan titled “A multidimensional study of the Latino-American narrative,” Emmett explores the history of laws like the Treaty of Paris, the Jones Act, Operation Bootstrap, and the Bracero Program, combined with interviews with Puerto Rican Americans about their experiences. “My research seeks to explore the US’s largely self-inflicted Latino immigration ‘problem,’ and simultaneously allows space for the voices of modern-day Puerto Rican Americans struggling with many of the same issues as those who came before them,” says Emmett. “I pose the question: How does legislation passed between 50 and 100 years ago still affect the lives of Latino Americans today?”

“Trade laws and work programs passed by the United States in nearby Puerto Rico and Mexico have weakened the economies of these already struggling countries for many years,” says Emmett Wood ’19. In a Plan titled “A multidimensional study of the Latino-American narrative,” Emmett explores the history of laws like the Treaty of Paris, the Jones Act, Operation Bootstrap, and the Bracero Program, combined with interviews with Puerto Rican Americans about their experiences. “My research seeks to explore the US’s largely self-inflicted Latino immigration ‘problem,’ and simultaneously allows space for the voices of modern-day Puerto Rican Americans struggling with many of the same issues as those who came before them,” says Emmett. “I pose the question: How does legislation passed between 50 and 100 years ago still affect the lives of Latino Americans today?”

Perspective

Nietzsche vs. Nihilism in America

By Derek Tollefson ’18

It’s hard to be optimistic about politics right now. For those committed to improving political life in America, it’s hard enough to figure out what can or should be done, let alone actually doing it, and thinking it’ll all work out in the end is just naive.

Nietzsche prophesied the advent of nihilism in Europe, and if he’d lived to see the holocaust, Stalin’s gulags, the starvation during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and the innumerable casualties of both World Wars in the century to follow, he could have said, “I told you so.”

Americans have every reason to be nihilistic: not only are we grappling with more intractable problems than we can count, but we’re exposed to these problems constantly, graphically, and intimately through social media information bubbles. Britain left the EU. People are publishing books and articles about the end of the nation-state system, the primary source of political identity and stability for most of the world over the last two hundred years. The doomsday clock is set at two minutes to midnight, and the man with the nuclear codes is a philandering reality TV host who doesn’t read books.

The writing, it would appear, is on the wall.

Perhaps these concerns are overblown. Perhaps everything will work out in the end. Perhaps not; I can’t say. But in uncertain times people look for certainty anywhere they can, and that is certainly dangerous. Existentialism, and Nietzsche in particular, offers a way to put humanity first without making feckless, empty promises of certainty and stability. In fact, Nietzsche revels in uncertainty, making it into a strength and not a weakness.

If things are moving too quickly to tell right from wrong, if the world is changing too rapidly to really make sense of it, then why not give up on making sense and doing what’s right, which were never really options in the first place, and just focus on making things better? It might require getting our hands dirty, but maybe they were never clean from the start.

Derek Tollefson graduated with a Plan in politics titled “No clean hands: The politics of revenge using Nietzsche and storytelling.” He is now working on the second issue of Milkfist, the literary journal he and a friend founded several years ago, and on finding a PhD program where he can build on his Plan portfolio.

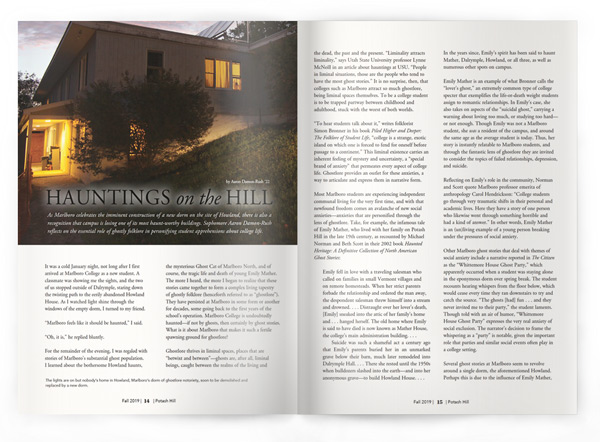

Hauntings on the Hill

by Aaron Damon-Rush ’22

As Marlboro celebrates the imminent construction of a new dorm on the site of Howland, there is also a recognition that campus is losing one of its most haunt-worthy buildings. Sophomore Aaron Damon-Rush reflects on the essential role of ghostly folklore in personifying student apprehensions about college life.

It was a cold January night, not long after I first arrived at Marlboro College as a new student. A classmate was showing me the sights, and the two of us stopped outside of Dalrymple, staring down the twisting path to the eerily abandoned Howland House. As I watched light shine through the windows of the empty dorm, I turned to my friend.

“Marlboro feels like it should be haunted,” I said.

“Oh, it is,” he replied bluntly.

For the remainder of the evening, I was regaled with stories of Marlboro’s substantial ghost population. I learned about the bothersome Howland haunts, the mysterious Ghost Cat of Marlboro North, and of course, the tragic life and death of young Emily Mather. The more I heard, the more I began to realize that these stories came together to form a complex living tapestry of ghostly folklore (henceforth referred to as “ghostlore”). They have persisted at Marlboro in some form or another for decades, some going back to the first years of the school’s operation. Marlboro College is undoubtedly haunted—if not by ghosts, then certainly by ghost stories. What is it about Marlboro that makes it such a fertile spawning ground for ghostlore?

Ghostlore thrives in liminal spaces, places that are “betwixt and between”—ghosts are, after all, liminal beings, caught between the realms of the living and the dead, the past and the present. “Liminality attracts liminality,” says Utah State University professor Lynne McNeill in an article about hauntings at USU. “People in liminal situations, those are the people who tend to have the most ghost stories.” It is no surprise, then, that colleges such as Marlboro attract so much ghostlore, being liminal spaces themselves. To be a college student is to be trapped partway between childhood and adulthood, stuck with the worst of both worlds.

“To hear students talk about it,” writes folklorist Simon Bronner in his book Piled Higher and Deeper: The Folklore of Student Life, “college is a strange, exotic island on which one is forced to fend for oneself before passage to a continent.” This liminal existence carries an inherent feeling of mystery and uncertainty, a “special brand of anxiety” that permeates every aspect of college life. Ghostlore provides an outlet for these anxieties, a way to articulate and express them in narrative form.

Most Marlboro students are experiencing independent communal living for the very first time, and with that newfound freedom comes an avalanche of new social anxieties—anxieties that are personified through the lens of ghostlore. Take, for example, the infamous tale of Emily Mather, who lived with her family on Potash Hill in the late 19th century, as recounted by Michael Norman and Beth Scott in their 2002 book Haunted Heritage: A Definitive Collection of North American Ghost Stories:

Emily fell in love with a traveling salesman who called on families in small Vermont villages and on remote homesteads. When her strict parents forbade the relationship and ordered the man away, the despondent salesman threw himself into a stream and drowned. . . . Distraught over her lover’s death, [Emily] sneaked into the attic of her family’s home and . . . hanged herself. The old home where Emily is said to have died is now known as Mather House, the college’s main administration building. . . . Suicide was such a shameful act a century ago that Emily’s parents buried her in an unmarked grave below their barn, much later remodeled into Dalrymple Hall. . . . There she rested until the 1950s when bulldozers slashed into the earth—and into her anonymous grave—to build Howland House. . . .

In the years since, Emily’s spirit has been said to haunt Mather, Dalrymple, Howland, or all three, as well as numerous other spots on campus.

Emily Mather is an example of what Bronner calls the “lover’s ghost,” an extremely common type of college specter that exemplifies the life-or-death weight students assign to romantic relationships. In Emily’s case, she also takes on aspects of the “suicidal ghost,” carrying a warning about loving too much, or studying too hard— or not enough. Though Emily was not a Marlboro student, she was a resident of the campus, and around the same age as the average student is today. Thus, her story is instantly relatable to Marlboro students, and through the fantastic lens of ghostlore they are invited to consider the topics of failed relationships, depression, and suicide.

Emily Mather is an example of what Bronner calls the “lover’s ghost,” an extremely common type of college specter that exemplifies the life-or-death weight students assign to romantic relationships. In Emily’s case, she also takes on aspects of the “suicidal ghost,” carrying a warning about loving too much, or studying too hard— or not enough. Though Emily was not a Marlboro student, she was a resident of the campus, and around the same age as the average student is today. Thus, her story is instantly relatable to Marlboro students, and through the fantastic lens of ghostlore they are invited to consider the topics of failed relationships, depression, and suicide.

Reflecting on Emily’s role in the community, Norman and Scott quote Marlboro professor emerita of anthropology Carol Hendrickson: “College students go through very traumatic shifts in their personal and academic lives. Here they have a story of one person who likewise went through something horrible and had a kind of answer.” In other words, Emily Mather is an (un)living example of a young person breaking under the pressures of social anxiety.

Other Marlboro ghost stories that deal with themes of social anxiety include a narrative reported in The Citizen as the “Whittemore House Ghost Party,” which apparently occurred when a student was staying alone in the eponymous dorm over spring break. The student recounts hearing whispers from the floor below, which would cease every time they ran downstairs to try and catch the source. “The ghosts [had] fun . . . and they never invited me to their party,” the student laments. Though told with an air of humor, “Whittemore House Ghost Party” expresses the very real anxiety of social exclusion. The narrator’s decision to frame the whispering as a “party” is notable, given the important role that parties and similar social events often play in a college setting.

Several ghost stories at Marlboro seem to revolve around a single dorm, the aforementioned Howland. Perhaps this is due to the influence of Emily Mather, as Howland is one of the buildings she is frequently said to haunt. Several students say that their time in Howland was marked by strange noises and disturbances in the night. In the words of one anonymous student cited in The Citizen:

I thought that my neighbors were just noisy. It sounded like they were dropping bowling balls and rolling marbles across the floor. When I would confront them they’d swear they didn’t know what I was talking about. Sometimes when the noise would get bad, I would go upstairs only to discover that no one was in the room above me, or worse yet, that the noises were absolutely not coming from upstairs, but rather, within my own walls.

In narratives such as these, the college student’s anxiety about noisy or otherwise disruptive neighbors is given a supernatural twist. Other stories recounted in The Citizen tell of uneasy sleep within Howland’s rooms. One Marlboro student described waking at 3:00 am “on the dot” every single morning, going outside, and walking the same path. Another said they woke up from a deep sleep with a feeling that “the other person in bed was not my partner” and that “there was someone in the corner.” The student then fell back asleep and later discovered that their partner had had an identical experience. These narratives express an anxiety around loss of sleep and communal living—anxieties all too familiar to busy college students.

One narrative of a student’s experiences at Marlboro North speaks to anxieties around being far from home on a remote, rural campus. The student describes not only a close bond with Ghost Cat, the benevolent feline spirit that is said to haunt the halls of Marlboro North, but also a more threatening supernatural force in the building. “I loved ghost cat,” writes the student in The Citizen, “and got the distinct feeling he was protecting and comforting me from the creepy business in the rest of the building.”

As with all forms of folklore, the ghostlore of Marlboro College is ultimately a form of cultural communication. In his book Interpreting Folklore, Alan Dundes states that folklore “provides a socially sanctioned framework for the expression of critical anxiety-producing problems as well as a cherished artistic vehicle for communicating ethos and worldview.”

Throughout the vast tapestry of Marlboro ghostlore, we see these functions in action. Each and every ghost story represents specific anxieties within the Marlboro student body. Some of these may be anxieties around college in general—noisy roommates, doomed relationships—while others are specific to Marlboro itself, particularly the narratives that focus on the school’s isolated location. As author Colin Dickey says in his book Ghostland, “We tell stories of the dead as a way of making sense of the living.”

Ghostlore helps students embrace the idea of college as liminal space, transforming the “strange exotic island” that is the Marlboro campus into a mysterious and magical place where anything can happen. Through ghostlore, the Marlboro student body grows closer as a community, ensuring that, much like their ghostly subjects, these stories will continue to haunt the Marlboro campus for many years to come.

Aaron Damon-Rush is a sophomore at Marlboro whose main area of interest is “narrative storytelling” in all of its forms— “basically just a fancy way of saying that I enjoy studying stories and the cultural significance they hold.” This article is adapted from an essay written by Aaron for the writing seminar Folklore in Literature and Pop Culture, for which he was awarded a Freshman-Sophomore Essay Prize in May. “Students in my spring 2019 Writing Seminar explored past and current definitions of ‘folk’ and reflected on how folklore and folk processes (transmission from person to person, variation, etc.) persist in the digital age,” says creative writing professor Bronwen Tate. “Aaron did a great job situating his findings within the context of scholarship, both on hauntings and on campus folklore.”

Death’s Covenant with Existence “The ‘whole abyss’ between the present and death is like the abyss between myself and the Other,” says Alex Quick ’19 in his Plan paper titled “The Other in Time.” Alex explores the ethics of 20th-century philosophers Martin Heidegger and Emmanuel Levinas as he grapples with death, which Heidegger said serves as a “total structuring of my temporality.” “For Heidegger, the present moment always has a relationship to death when I am moving toward death in all of my moments,” says Alex, who after graduating joined the Peace Corps in Nepal. “The nothingness in death is inseparable from this present in being.” But for Levinas, death cannot be the primary force that structures time. “Death is not ushering the future into the present because death has no relationship to the present,” says Alex.

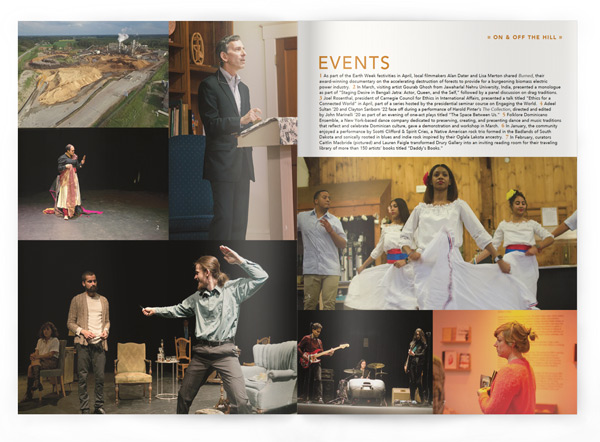

On and Off the Hill

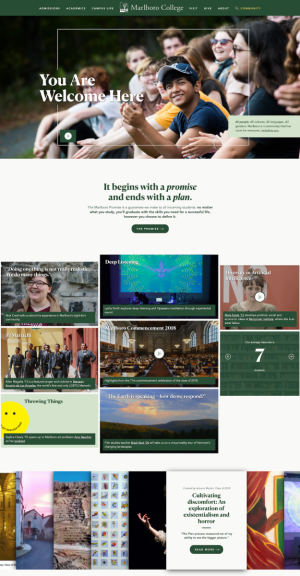

New Website Puts Stories First

One of the most visible and exciting outcomes of last year’s Reimagining Marlboro effort (Potash Hill Spring 2019) is the college’s new website, which went live in July. Supported by a generous grant from the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation, the vibrant new site is designed to highlight many of the important strengths that surfaced during the “reimagining” process.

One of the most visible and exciting outcomes of last year’s Reimagining Marlboro effort (Potash Hill Spring 2019) is the college’s new website, which went live in July. Supported by a generous grant from the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation, the vibrant new site is designed to highlight many of the important strengths that surfaced during the “reimagining” process.

“Since the launch of Marlboro’s former website in 2014, alumni, faculty, and students have often shared feedback that they wished for more dynamic features, streamlined navigation, and a fresher look that feels more like Marlboro,” says Carla Snook, director of communications and marketing. “This new site is much more dynamic, designed to make better use of stories, videos, profiles, and events to bring Marlboro to life for prospective students and other visitors.”

“We are enthralled with your college, and wanted to design a website true to your distinctive curricular model and campus culture,” says Jason Pontius, president and creative director of White Whale Web Services, which collaborated with faculty, staff, and students to create the new site. “What makes Marlboro amazing is a combination of the people, the place, and the curriculum, so we tried to get these elements front and center to draw visitors in.”

White Whale’s thorough development process began almost two years ago, and has included many visits to campus and meetings with community members. Three years, if you count the “tiny college” workshops also hosted by the Endeavor Foundation and facilitated by White Whale (“Tiny Colleges Matter,” Potash Hill Fall 2016).

Features of the site include inviting new videos and an articulation of the “Marlboro Promise,” the primary outcome of the Reimagining Marlboro process, directly on the home page. The page also features a “garden” of always-changing stories, profiles, excerpts, and vignettes that bubble up from other areas of the site, as well as a dynamic array of teasers from past Plans that will take you to excerpts and information on each one in a virtual Plan Room.

True to Marlboro’s character, the new website is also more egalitarian in its content creation, inviting faculty, students, and staff to contribute content for a rich mix of stories and perspectives that truly represents Marlboro’s campus community. Visitors exploring the general fields of study offered at Marlboro will find Plans, profiles, and stories that support each and provide rich context.

“Rather than telling you about Marlboro, as our old website tended to do, the new website shows you Marlboro,” says Carla. “We are so thrilled to have this new resource for prospective students and other community members, and look forward to any comments for further improvement.”

NEH Supports Data Humanist Certificate

Marlboro College has always provided a wealth of interdisciplinary coursework, including courses drawing important links between the humanities and sciences. Now, with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant, the college is positioning itself to offer a new undergraduate Data Humanist Certificate Program, making these links even more explicit and demonstrating students’ preparedness for the workplace.

“There is an obvious utility in a student being able to say to a prospective employer, ‘I did some relevant data work,’” said Adam Franklin-Lyons, history professor and one of the faculty members who applied for the grant. “They might have studied literature, but they also worked with a state agency or nonprofit on a data project. If they are applying to do something similar, I think that’s a no brainer.”

The $30,000 NEH Humanities Connections Grant will support the development of a certificate program that provides clear links between humanities coursework and data-driven classes in mathematics, computer science, and biology. The certificate will involve taking two data classes, two humanities classes, and two designated “bridge” classes that are co-taught by faculty from both areas. It will also involve a capstone project that connects with the community in some way, through working for either a government agency, nonprofit, or other organization.

“The ideal is to have four bridge classes in rotation, so they each come around every two years,” said Matt Ollis, math professor, who is also on the grant. “Adam and I will co-teach Cartography once every two years, just as we have in recent years. And Jenny Ramstetter (biology) and Kate Ratcliff (American studies) will continue the Culture and Ecology of the Western US class they’re teaching this semester.”

Other bridge courses will take some development, but one about migrations among humans and other species, to be co-taught by Jenny and Rituparna Mitra (literature and writing), is in the planning stage. The grant team plans to collaborate with colleagues and finalize the certificate program through the Marlboro faculty for a proposed roll-out in fall 2020.

Marlboro Designated Changemaker Campus

In July, after a long and rigorous selection process, Marlboro College was pleased to announce that it has been designated a Changemaker Campus by Ashoka U. One of approximately 45 leading colleges and universities globally recognized by Ashoka U, Marlboro brings its unique values of shared governance and self-designed learning to this network.

In July, after a long and rigorous selection process, Marlboro College was pleased to announce that it has been designated a Changemaker Campus by Ashoka U. One of approximately 45 leading colleges and universities globally recognized by Ashoka U, Marlboro brings its unique values of shared governance and self-designed learning to this network.

“Institutions in the Changemaker Campus Network set the bar for social innovation and social change in higher education,” says Kate Trzaskos, assistant dean of career education and one of the change leaders who have guided Marlboro through the designation process. “Marlboro is thrilled to be a part of this group, and to share what we have learned through our innovative curricular design and system of community governance.”

Ashoka U is an initiative of Ashoka, the world’s largest network of social entrepreneurs and changemakers. The initiative recognizes colleges and universities globally that, like Marlboro, have embedded social innovation and changemaking into their programming, culture, and operations and are committed to partnering to make this the new norm across higher education. Learn more at marlboro.edu/changemaker.

Students Bring Leadership to Smokies

During spring break in March, five students and OP director Adam Katrick ’07 made a trip to Great Smoky Mountains National Park for hiking, botanizing, and exploring the history of this extraordinary mountain range in Tennessee and North Carolina. The two-week trip was expertly planned and led by students Claire O’Pray ’20 and Lydia Nuhfer ’20—a testament to their leadership skills, including the experience they have gained at Marlboro.

“Being a Bridges leader for the past two years, planning the menu for the Yellowstone trip last year, and taking the Outdoor Leadership class all helped a lot in terms of feeling like I had a handle on the logistical aspects,” says Claire. “Leading this trip was super rewarding. Having people laugh every night, or just sit in silence at a waterfall, and knowing that I made that happen, felt good.”

The group hiked almost every day, walking through biologically diverse and unusual forests to visit waterfalls, caves, and historic sites from the European pioneer era. They also explored Cherokee, North Carolina, and learned about the Indigenous people who thrived in this region for centuries before most were forcibly removed. In the evenings, the hikers shared stories, poetry, music, games, and the camaraderie of adventures together.

“I felt lucky to have the opportunity to plan and lead something from scratch like this as a student—you wouldn’t get the opportunity to do that at a lot of schools, but it’s something the OP here values and prepares us well for,” says Lydia. “I’m studying plant ecology and botany, and the Smokies are a great place to do that, with the highest tree species diversity in the United States.”

One of the many memorable moments occurred while hiking to Mingo Falls, when they saw some graffiti in a six-year-old’s handwriting that read “I love the woberfol.” “We repeated this at every waterfall we went to, and there were many,” says Lydia, who also memorably “dragged” everyone to Waffle House. “In some sense I helped plan this whole trip to Appalachia just so I could go to Waffle House. That’s not entirely true, but it’s a little true.”

On the long drive home, a stop in Maryland at Assateague Island National Seashore was a balm for the weary travelers. It was a gray and stormy afternoon, so they were the only visitors there on the beach trails, where they hiked alongside some of the island’s famous wild horses.

“As soon as we got to the beach, everyone went silent and did their own thing,” says Claire. “It was beautiful to watch some people just kneel down and look at the water, and others run into the waves. I just ran along the sand until I got tired. It was a really quiet, special moment that I loved sharing with everyone there.”

Asylum Seekers Find Respite in Marlboro

In May, after many months of preparation and waiting, two women from Honduras arrived in Marlboro to live, thanks to a partnership between the college and members of the town community. With support from the local Community Asylum Seekers Project (CASP), the effort offers shelter to these immigrants, who would otherwise be living in detention centers, while they wait out the long process of obtaining citizenship.

“I saw this as an enormous learning opportunity and a good reflection of our values,” says President Kevin. “It gives us, as a learning community, a really practical way to play a small but important role in trying to address a major challenge confronting our country and society.” Kevin was approached by two Marlboro residents, Francie Marbury and Edie Mas, who were interested in accepting asylum seekers into the community, but were concerned that living in the rural village would be too isolating. It was agreed that the college would house them during the academic year, when they could be a part of the campus community and participate in meals, events, and other campus happenings.

“I feel really lucky to be involved with this,” says biology professor Jaime Tanner, director of the World Studies Program and a member of the committee that worked to welcome the asylum seekers. Other college community members involved included Spanish language and literature professor Rosario de Swanson, visual arts faculty emeritus Tim Segar, and Emma Huse, former experiential learning and global engagement coordinator, who participated as part of her capstone project at SIT Graduate Institute.

“Right now, people feel a sense of helplessness in the face of the current administration’s policies regarding refugees and asylum seekers,” says Jaime. “This is really a wonderful opportunity to express how much we do welcome others, especially those struggling to find a safe haven.”

It has been a big adjustment for the two women, who come from a suburban area outside the capital city, Tegucigalpa, and were surprised at how rural it is in Marlboro—a car is necessary to get almost anywhere. But they have felt very welcomed by the town community, where they stayed in a private home for the summer, helped residents with their conversational Spanish weekly at the Marlboro Community Center, and even shared some of their amazing Honduran cooking.

These new friends are the fifth family to be welcomed into southern Vermont through the auspices of CASP, which was founded in 2015 for this purpose and has seen its mission grow more urgent in recent years. The others are being hosted in Brattleboro, Rockingham, and Westminster. CASP asks all of us to respect their confidentiality, as their citizenship status may be precarious. Meanwhile, the campus community welcomes them while they wait for their first court hearing, probably sometime next year.

College Stays the Course on Title IX

Last fall, the US Department of Education proposed new Title IX regulations that, if made into law, could require significant changes in how Marlboro addresses claims of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and similar rights violations. Despite these new recommendations, and the clamor of debate about their possible impacts, Marlboro has continued to provide a coherent and compassionate response system with many important improvements in recent years.

Last fall, the US Department of Education proposed new Title IX regulations that, if made into law, could require significant changes in how Marlboro addresses claims of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and similar rights violations. Despite these new recommendations, and the clamor of debate about their possible impacts, Marlboro has continued to provide a coherent and compassionate response system with many important improvements in recent years.

“Regardless of the shifting political landscape in Washington around Title IX, Marlboro is still operating under best practices and from a student-centered perspective,” says Patrick Connelly, dean of students. “I think that schools like us that have any kind of moral center are saying, ‘We know what is best practice even if Washington doesn’t fully agree with it.’ We’re going to stay the course as long as there is no legal requirement that we implement the recommendations.”

“Marlboro has worked hard over the years to ensure that we have dealt with Title IX cases fairly, thoroughly, and with respect to our shared community values of safety, learning, and inclusiveness,” said President Kevin in a December letter to the community responding to the new recommendations. “The community has done this work deliberately and carefully in consultation with our Title IX counsel, as well as with consultation with community members. We plan to continue this approach and to address the proposed regulations and implementation of them in this manner.”

As described two years ago in Potash Hill by Robyn Manning-Samuels ’14, then coordinator of sexual respect and wellness, the starting point for Title IX policy at Marlboro and other colleges and universities was the 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter issued by the Obama administration (“Positive Sexuality on Campus,” Fall 2017). Since then, Marlboro has made great strides in prevention and sexual wellness programs, as described by Robyn, but also in adjudicating sexual misconduct cases and providing support for all parties involved. Part of this comes with having a dedicated Title IX coordinator, Brattleboro attorney Jean Kiewel, rather than pinning the role on the dean of students.

“It’s unusual to have someone of Jean’s caliber and qualifications at a school this size,” says Patrick. “It’s a serious challenge to be the dean of students, to support and grow community, when you’re also the investigator and the adjudicator for Title IX cases. Being able to fully be the dean of students is a luxury that doesn’t exist on many small campuses. Meanwhile, I am able to support a Title IX team that meets regularly and is proactive, not just about investigations but about the educational aspects and constant, ongoing building of a safe and respectful community. That’s really unusual too.”

That team includes Megan Grove, coordinator for campus prevention, intervention, and advocacy, who ably filled Robyn’s boots as survivor advocate, but has also been expanded to include Dylan Muller, assistant director of residence life and community standards, who acts in the new role of respondent advisor. The team is completed by Jay Sparks, director of campus safety, who is a resource for students and coordinates reporting by contract security officers and on-call staff.

“This expanded team is much more qualified to meet the needs of students and respond to concerns,” says Jean. “Not only are we totally on target for meeting the mandates for Title IX, we are doing some really great work that is over and above these mandates. These include offering informal resolution options to cases, and a recent memorandum of understanding with the Vermont State Police that can expedite investigations, if desired. Our Title IX panel has a diversity of conscientious faculty and staff who enthusiastically volunteer their time for the good of the community.”

“This expanded team is much more qualified to meet the needs of students and respond to concerns,” says Jean. “Not only are we totally on target for meeting the mandates for Title IX, we are doing some really great work that is over and above these mandates. These include offering informal resolution options to cases, and a recent memorandum of understanding with the Vermont State Police that can expedite investigations, if desired. Our Title IX panel has a diversity of conscientious faculty and staff who enthusiastically volunteer their time for the good of the community.”

“We are working toward our team and volunteers having trauma-informed training,” says Megan. “It’s important to know how people hold trauma in their bodies and understand that the way trauma manifests can vary widely. One of our main objections to the new Title IX recommendations is just how dangerous and irresponsible it is to put trauma survivors in face-to-face hearings with cross-examinations.” The Title IX team is not entirely ruling out all of the new recommendations, and have been able to distinguish those they feel are appropriate or potentially harmful. For instance, more accommodations are allowed for respondents if needed, such as academic or housing accommodations, and that is in keeping with Marlboro’s practice and approach.

But the team fears the overall effect of a number of the regulations, if enacted, could make the process more limited in scope, as well as more stressful and expensive. The team feels it could lead to less reporting of sexual harassment and sexual violence at Marlboro. They are waiting for more legal tests of the new recommendations, but in the meantime they are well-positioned and well-qualified to respond to cases on campus.

“I can confidently say that in the state of Vermont, for colleges that aren’t Middlebury or UVM, we’re doing it the best,” says Patrick. “It truly is amazing, given our resources and given the added complexity of community governance. We’re nailing it.”

Interns Bring New Energy to Farm and Forest

From May through August, two new interns contributed significantly to ongoing sustainability efforts in two key areas. Jacob Lepkoff and Taliesin Haugh brought a wealth of experience to their roles in the community farm and the forest reserve, respectively, and helped move the college toward goals in each case.

“These new community members help keep things moving over the summer, when there is most to be gained in managing both the farm and the forest reserve, but when our capacity is usually at its minimum,” says Todd Smith, chemistry professor. As the sustainability projects manager, Todd was instrumental in searching for and hiring these two very qualified interns. “This was a trial run for this summer, to be assessed for possible repetition in future years.”

“Working with any biological system, you interact with so many living pieces of that system,” said Jacob, who graduated from Sterling College with a bachelor’s in sustainable agriculture and has worked on a number of farms for 10 seasons. “It’s a joy to work in a living system because you are forced to observe and guess continuously. It is very engaging and rewarding. With every new experience I feel I’m offered a new opportunity to improve my guesses.”

Jacob worked closely over the summer with students Claire O’Pray ’20 and Emerson Gray Koetter ’22, who were able to pursue their own research interests as well as maintain the farm and produce some food. Taliesin, who recently completed his master’s in sustainable development at SIT Graduate Institute, worked more independently on the forest reserve, but was available as a resource for students conducting research there such as Hailey Mount ’20.

“This internship is an exciting opportunity to build the key systems knowledge, frameworks, and skills required to help facilitate a larger societal shift toward sustainable land management, as well as place-based community building,” said Taliesin. “Marlboro took on a huge commitment with this forest reserve, and it’s exciting but daunting to be here at the ground floor of decades of continuous work and research. I hope we set a good foundation for future students and faculty to build on for years to come.”

Three Longtime Faculty Find New Horizons

Marlboro takes pride in how students find their passions through exploring new ideas and perspectives, and how the college’s interdisciplinary approach uniquely prepares them for new horizons. That is no less true for our faculty, three of whom are retiring this year to focus on new projects or directions inspired by their many years spent with Marlboro students and colleagues. Meg Mott (politics), John Sheehy (literature and writing), and John Willis (photography) will all be missed, but the community looks forward to seeing where their next steps take them.

“My favorite part about teaching at Marlboro has been the luxury and solace of teaching old books to a rambunctious group of young thinkers,” says Meg, who has taught politics since 1999. After 20 years, she will be finishing up with her last Plan students this year. “I will miss sitting on the wall in front of the dining hall and watching new and returning students take charge of the campus in September and October.”

“My favorite part about teaching at Marlboro has been the luxury and solace of teaching old books to a rambunctious group of young thinkers,” says Meg, who has taught politics since 1999. After 20 years, she will be finishing up with her last Plan students this year. “I will miss sitting on the wall in front of the dining hall and watching new and returning students take charge of the campus in September and October.”

In popular classes like Debating the American Dream and American Political Thought, Meg boldly blended constitutional law with political theory, two subfields of political science that often don’t have much overlap. She also launched an ambitious semester intensive titled Speech Matters, in fall 2017 and spring 2017, which dove deeply into reframing the debate on addiction and life after incarceration, respectively.

“Thanks to the curricular freedom afforded at Marlboro, I’ve been able to make connections between Machiavelli and Antonin Scalia, Madison and Sandra Day O’Connor,” Meg says. Her political expertise also extended from the classroom to Marlboro’s shared governance model, Community Court, and Town Meeting, where she often served as “parliamentarian.” “Marlboro gave me many opportunities to think out loud in public. Controversial discussions in Town Meeting always sharpened my thought process, and I am so grateful for my worthy opponents.”

Meg’s next adventure involves political theory, the Bill of Rights, and—wait for it—choral music. In the summer of 2017, she created a series called Debating Our Rights, which has run at the Putney Public Library and the Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro. The Vermont Humanities Council recently signed her on as one of their speakers, ensuring that the series will be touring around the state. In February 2020, she’ll be presenting on the 19th Amendment at the Vermont State House. “We begin with a look at the political theory behind each of the amendments, the Supreme Court interpretations, and the popular debates those decisions have spawned,” says Meg. What’s more, starting this fall, she’ll be collaborating with composer Neely Bruce of Wesleyan University, who has set the Bill of Rights to music.

“Neely works with community singers, and I lead workshops on the theory and interpretations of select amendments. We conclude with a public performance and discussion on these precious liberties. We are beginning with a performance/workshop in Augusta, Maine, on the First Amendment, and intend to hit each of the 50 states by 2024.” By that time, Meg also hopes to have finished and published her book in progress, Good Clash: The Art of Productive Disagreement. See her recent BCTV presentation on the subject at bit.ly/33qM2xc.

“The political theorist is committed to thinking outside the box or, as Plato might say, ‘thinking outside the cave,’” wrote Meg in a Spring 2016 Potash Hill editorial. The community can rest assured that Meg will remain ever vigilant in this regard, guiding the masses from the mind-numbing shadows of the machine.

• • •

“I liked that Marlboro gave me the freedom to teach what I wanted, when I wanted, and how I wanted,” says John Sheehy, who retired this fall after teaching literature and writing at the college since 1998. “I also liked the way teaching at Marlboro stretched me as a teacher, making me learn new things, and new approaches to old things. But, really, the students—Marlboro students are a joy.”

“I liked that Marlboro gave me the freedom to teach what I wanted, when I wanted, and how I wanted,” says John Sheehy, who retired this fall after teaching literature and writing at the college since 1998. “I also liked the way teaching at Marlboro stretched me as a teacher, making me learn new things, and new approaches to old things. But, really, the students—Marlboro students are a joy.”

With titles like Apocalyptic Hope: The Literature of the American Renaissance and Tell about the South: The South in the American Literary Imagination, John’s literature seminars have covered everything from Faulkner to Emerson, Toni Morrison, Norman MacLean, and Cormac McCarthy. He loves books, and has an almost reverential regard for Moby Dick.

“When you teach a book, and this is true of many books that I love, there are many books that you can find the bottom of,” John said in a Fall 2014 Potash Hill interview. “You teach it once, you teach it twice, you teach it 10 times, and in the end of that you’ve found the edges of it, you know all of the things that are in it. And Moby Dick is not like that. I’ve been teaching it for 20 years and every time I teach it…there’s a bottom somewhere there but I haven’t found it. It’s a beautiful book.”

John explains that writing is an essential part of the learning process because it forces people to organize and present their thoughts with discipline, something people don’t always do when they are simply reading or talking about what they’ve read. For several years he led the Summer Writing Intensive, a weeklong workshop geared toward bringing together veterans as well as civilians through the art of writing, an experience he reflected on in a Chronicle of Higher Education editorial titled “Taking the Fight to the Page.”

It will come as no surprise to students in his Crime and Punishment class that John’s next move is going to law school, something he has contemplated since before his graduate work in literature. He’s not sure where it will lead, but has interests in public interest law, education law, or even going back to teaching.

“I’ve loved teaching legal writing, and would really love the opportunity to develop that as part of a pre-law curriculum somewhere,” says John. “We’ll see. For now, I’m kind of glad to be in the position of not knowing. It’s been a while since I didn’t know what tomorrow would look like.”

What John is certain of is that he will miss pretty much everything about Marlboro, especially teaching and the relationships he’s had with colleagues and, most of all, with students. “Marlboro has more or less made me who I am, so my time at Marlboro has helped inform this new adventure of mine in every conceivable way.”

• • •

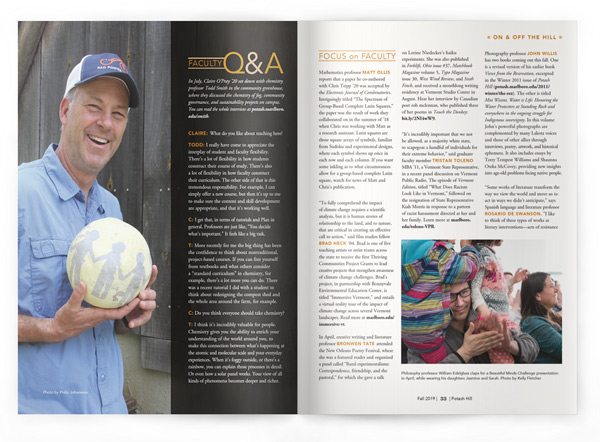

Photography professor John Willis is also retiring after being at Marlboro for 29 years, having started as a part-time adjunct faculty in 1990. He actually first taught a class at the college in 1980, when he had just graduated from Evergreen State College and had moved to the area. Someone invited him to the sauna at Marlboro, and there he learned from students that they were working on building a darkroom but didn’t have a photography teacher. He gladly taught an Intro to Photography class in exchange for taking an art history class with Willene Clark.

Photography professor John Willis is also retiring after being at Marlboro for 29 years, having started as a part-time adjunct faculty in 1990. He actually first taught a class at the college in 1980, when he had just graduated from Evergreen State College and had moved to the area. Someone invited him to the sauna at Marlboro, and there he learned from students that they were working on building a darkroom but didn’t have a photography teacher. He gladly taught an Intro to Photography class in exchange for taking an art history class with Willene Clark.

“The photography program was started by students, just like the film program,” says John, who will continue working with Plan students for this academic year. “I had six students who worked like crazy for no credits, and we set it up in the science building with a darkroom in a mop closet. When I left there was enough interest that they started having part-time adjunct faculty.”

John has enjoyed teaching students who find interesting ways to combine fine arts photography with their other academic work, and has sponsored Plans that spanned the curriculum, from foreign languages to physics. He has challenged students to take photographs that comment on the images they capture, and sees the classroom as a place for constructive criticism.

“I’ve learned so much from the students doing Plans,” says John. “I love the interdisciplinary nature of Marlboro. Teaching the same class over and over, including basic things like ‘this is how a camera works,’ could be boring. What makes it really amazing and interesting is how each student comes to it differently and does different work.”

John is also well known for co-founding In-Sight Photography Project, a Brattleboro-based youth arts program that uses photography as a medium to empower young people to find their own creative voices. Working with five Marlboro Plan students he also co-founded Exposures, In-Sight’s cross-cultural youth arts program that brings participants together from Vermont, Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, and other communities to expand artistic and cultural horizons.

In the coming years John is planning on focusing more on his own work, collaborating with other artists, and probably traveling. He and his wife, Pauline, a nurse, have talked about spending part of the year abroad, applying for Fulbright fellowships, and perhaps even joining the Peace Corps. John credits Marlboro with opening his eyes to the value of travel, having participated in faculty-led trips to Cuba, China, Japan, Cambodia, Pine Ridge Reservation, and the Navajo Nation.

“One way Marlboro affected my life was waking me up to the realization of how amazing the world is, and seeing different cultures and traditions,” says John. “That whatever I grew up thinking was normal is really a construct of my circumstances, and that it’s really helpful to get to know people from different circumstances.”

Also of Note

In May, library staff held their Second Annual Rice-Aron Library Rice Cook-Off, pitting staff members against each other in a heated competition for the best rice dish, literary alluding rice dish, or Rice-Aron Library–alluding rice dish. Despite some stiff competition from the likes of homemade mochi, dragon rolls, and a Rice Krispy treat in the shape of a mouse and called Of Rice and Men, the first prize went to Kate Trzaskos (pictured right), assistant dean of career education, for her cauliflower-rice A Tale of Two Rices. Kate will proudly display the coveted, rice-encrusted, gold-painted trophy until next year.

“I wanted to explain how I see in Spinoza’s philosophical system a way for white Americans to engage in antiracism work as a project of self-love and self-liberation,” says Anna Morrissey ’20, who presented their thoughts at a special summer Collegium Spinozanum at University of Groningen, Netherlands, in July. Anna went there with politics professor Meg Mott, who presented a paper on Spinoza and sexual violence at the same symposium. “Spinoza reveals that to ascribe to racist ideology, consciously or not, is to deny oneself a clear understanding of one’s reality, one’s power, and oneself,” says Anna, who was lauded by other participants for combining Spinoza and critical pedagogy.

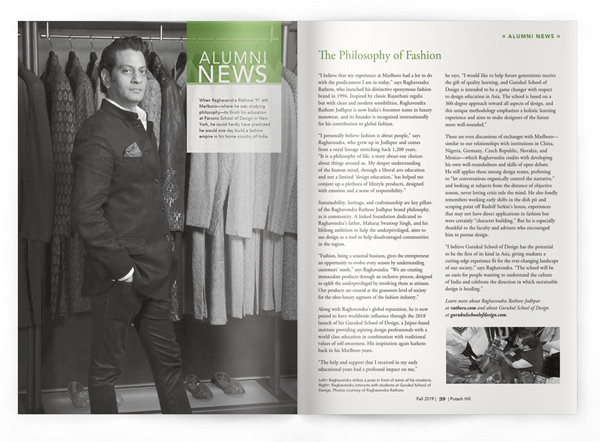

In March, The Chronicle of Higher Education ranked Marlboro near the top of the heap in a list awkwardly titled “Where are students most and least likely to be taught by tenured and tenure-track professors?” Marlboro was ranked #2 among four-year private nonprofit institutions, bested only by—some of you may have heard of it—Yale University. Despite its diminutive size, Marlboro rose to the top of the list thanks to a high percentage of tenured or tenure-track faculty (87.5 percent) and the low ratio of students per tenured or tenure-track faculty (7:2). Read more.