Winter 2012

Editor’s Note

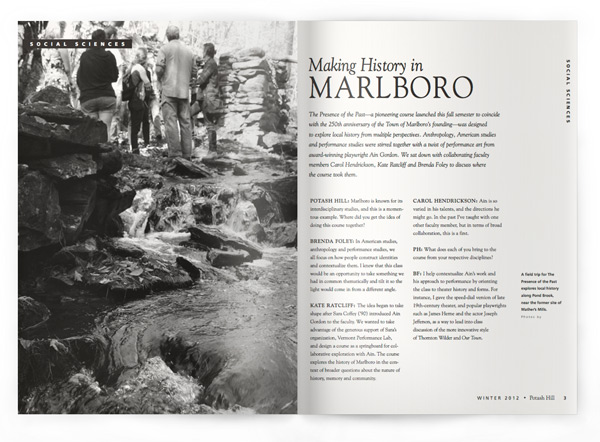

“It’s like trying to guess what Shakespeare was up to,” said Kevin Gardner, author of The Granite Kiss and husband of theater professor Brenda Foley, hence the apt reference. Kevin was referring to the challenges of interpreting the maze of stone walls, pens and cellar holes left by Marlboro’s first settlers. He and local historian Forrest Holzapfel were leading a field trip to the historic Bishop homestead, at the base of Hogback Mountain, as part of a course this fall semester called The Presence of the Past. One of the central lessons in this class was that much of what we call historic “truth” is subject to interpretation.

You will find several perspectives on the past in this issue of Potash Hill, from the minutia of Marlboro’s early history to alumnus Art Magida’s colorful assessment of prewar Berlin. Art history professor Felicity Ratté sizes up medieval monumental architecture of the Islamic Mediterranean, while alumna Molly MacLeod focuses on the recent past and hopeful future of some of New Jersey’s busiest residents. You’ll learn what students and faculty have been doing on campus, and what alumni are doing almost everywhere else. I encourage you to share your own interpretation of what you find in this issue. You can view responses to the Summer 2011 Potash Hill here.

—Philip Johansson, editor

Front cover: Reflection of Carsi Mosque and National Museum on Kosovo Parliament, Prishtina, Kosovo, part of Colby Silver’s fieldwork in the Balkans.

Table of Contents

Making History in Marlboro

The Presence of the Past—a pioneering course launched this fall semester to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the Town of Marlboro’s founding—was designed to explore local history from multiple perspectives. Anthropology, American studies and performance studies were stirred together with a twist of performance art from award-winning playwright Ain Gordon. We sat down with collaborating faculty members Carol Hendrickson, Kate Ratcliff and Brenda Foley to discuss where the course took them.

POTASH HILL: Marlboro is known for its interdisciplinary studies, and this is a momentous example. Where did you get the idea of doing this course together?

BRENDA FOLEY: In American studies, anthropology and performance studies, we all focus on how people construct identities and contextualize them. I knew that this class would be an opportunity to take something we had in common thematically and tilt it so the light would come in from a different angle.

KATE RATCLIFF: The idea began to take shape after Sara Coffey (’90) introduced Ain Gordon to the faculty. We wanted to take advantage of the generous support of Sara’s organization, Vermont Performance Lab, and design a course as a springboard for collaborative exploration with Ain. The course explores the history of Marlboro in the context of broader questions about the nature of history, memory and community.

KATE RATCLIFF: The idea began to take shape after Sara Coffey (’90) introduced Ain Gordon to the faculty. We wanted to take advantage of the generous support of Sara’s organization, Vermont Performance Lab, and design a course as a springboard for collaborative exploration with Ain. The course explores the history of Marlboro in the context of broader questions about the nature of history, memory and community.

CAROL HENDRICKSON: Ain is so varied in his talents, and the directions he might go. In the past I’ve taught with one other faculty member, but in terms of broad collaboration, this is a first.

PH: What does each of you bring to the course from your respective disciplines?

BF: I help contextualize Ain’s work and his approach to performance by orienting the class to theater history and forms. For instance, I gave the speed-dial version of late 19th-century theater, and popular playwrights such as James Herne and the actor Joseph Jefferson, as a way to lead into class discussion of the more innovative style of Thornton Wilder and Our Town.

CH: I’m a learner when it comes to my own state and town, so I look to Kate for insights into history as well as wonderful readings. She keeps us honest and straight about historical facts.

KR: As someone trained in U.S. social and cultural history, I bring a wider historical context to some of the local issues we have been studying. And Carol brings expertise with fieldwork as well as a special attentiveness to material objects. I think of her as our “materials” person.

CH: And sort of “wild idea” person.

KR: And also I want to add the “cross-cultural comparative context” person. Carol can relate Guatemala to just about any subject and make it a rich point of comparison.

CH: And it’s been great having Brenda there too because two of the texts we read were plays, Our Town and Will Eno’s Middletown.

BF: I am always encouraging us to ask the question “Who is the audience?” in any piece of text, photo, pamphlet or public event—and to weigh the stated intention against the performed action. So, I point out and critique as a performance that which was not necessarily constructed nor intended to be received as one.

BF: I am always encouraging us to ask the question “Who is the audience?” in any piece of text, photo, pamphlet or public event—and to weigh the stated intention against the performed action. So, I point out and critique as a performance that which was not necessarily constructed nor intended to be received as one.

KR: These different disciplinary backgrounds—as well as the students’ own backgrounds—create a rich, multilayered quality to the class and the discussions.

PH: And what does Ain Gordon bring into this heady mixture?

BF: In theater and performance, my interests have always been in that which is less readily apparent or easily articulated. Ain is ever after the elusive; no moment, no detail, no historical anecdote is refuse. For Ain, in all that detritus of the past lies potential.

KR: Ain brings a creative skepticism about the whole enterprise of history. As he says, “The idea that history is knowable is a conceit of history.” Ain is drawn to the gaps, to the silences, to the margins, to that which is clearly unknowable. And his aesthetic is to continually bring attention to the constructed nature of the narrative that he’s creating. Over the past several decades, there has been an ongoing conversation about the uneasy relationship between truth and our accounts of it. Historians will say yes, we need to recognize that what we find in the past is always shaped by the cultural categories and assumptions we bring to the work. These postmodern insights are generally acknowledged, but there’s still an impulse to create a story that is more seamless than the kind of work that Ain is doing. He’s an artist, and I’m a professional historian. But the tension between those worlds is incredibly rich and interesting and fruitful.

PH: How has this course added to your understanding of the minutia of local history?

KR: Newton’s History of the Town of Marlborough is the bible of local history. Everybody cites Newton. So it’s been interesting to read Newton and think of him not as a container of facts about Marlboro, but as a historical figure himself, someone interpreting the world through the lens of his own historical moment.

CH: For instance, the language and content of Newton’s letters to his daughter is significantly different from his formal history. That’s really interesting in the context of our course.

BF: In the class we talk about people and places inscribing and performing their own history. We all leave traces, marks, impressions in our wake whether we want to or not. There are the calculated inscriptions like speeches and legislative acts, marriages and partnerships, and choices about whether we set off on our own roads less taken. And “places” make parallel choices, by committee or decree or accident, as to how they want to present in life—whether the town green gets picket fences or stone walls or who gets to lead the Fourth of July parade.

KR: We think of the iconic symbol of the New England landscape—the white steepled church and the orderly commons—as representing “traditional” New England, but that particular version of the town center was the product of a specific moment in the early 19th century. Interestingly, multiple towns in this region, including Newfane, Marlboro and Brattleboro, originally sited their meetinghouses on top of hills, and later moved them down to a more central commons. At this same time, boosters throughout New England set out to improve the landscape of the town common. They looked around and saw ungraded roads criss-crossed with oxcart ruts and unsightly sheds to protect the horses in bad weather. Marlboro’s village center has included over time an ashery, a tannery, blacksmith shop, a wheelwright shop, a wagon maker, a chair factory—industry, all right there. In the landscape aesthetic that was emerging, these activities had no place in the central village district. The new and improved village commons with its white paint and stone walls was seen as a sign of progress, not as an evocation of some traditional landscape.

CH: That was interesting to me, because when the Spanish came to what is now Latin America, they had this vision of what a city center was—a plaza—and they often built right on top of pre-existing structures. Today you can see colonial Catholic churches that were built on top of Maya temples right on the edge of plazas. All of this reflects deep roots that go way back into Maya and European pasts. So, to find out that the New England commons is a 19th-century development, as opposed to something that was there for years and years, was a revelation to me.

PH: What are some of the creative anthropological, historical, theatrical outcomes students are coming up with?

CH: We’re really pushing students to think creatively beyond a term paper and come up with something that is relevant to the class or the history of Marlboro or southeast Vermont and that challenges them to think in different ways.

KR: We’re also trying to get them to communicate what they’ve learned to a broader audience. For example, one student is writing letters between Marlboro College students in different eras; another is creating a diary based on the life of Mrs. Whitmore, a midwife and early settler; and a third is writing a play based on the idea of disease and illness in the late 18th century and how high mortality rates affected the local population.

CH: These creative projects, then, loop back into the realm of needing to require students to know historically specific details, what are considered “facts.” A student writing a diary or a set of letters from a particular era needs to know a lot about that era and how people would have written and what allusions they would have made—but not in a 21st-century way.

BF: What we’re exploring in this class is the extraordinarily rich historical detail available to students who take the time to reach into creaky attics and small town archives. They uncover inscriptions left by people who hadn’t necessarily thought of their records as a performance but who must have anticipated an audience of, at least, one reader. And in that act of communication lies a kind of inscribed performance.

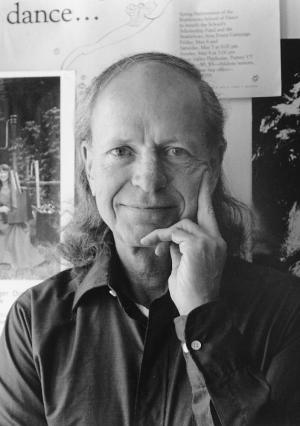

Ain Gordon (right) is a three-time Obie Award–winning playwright, director and actor whose work deals with issues of place and memory by unearthing disappearing history. His recent work includes A Disaster Begins, about one woman’s bond with the hurricane of 1900 in Galveston, Texas, and In This Place…, inspired by the first free African-Americans to build their own home in Lexington, Kentucky. Ain is a visiting artist at the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, artist-In-residence at the Center for Creative Research and co-director of the Pick Up Performance Co(s). He first came to Marlboro as part of the Embodied Learning Symposium in April (Potash Hill, Summer 2011).

Ain Gordon (right) is a three-time Obie Award–winning playwright, director and actor whose work deals with issues of place and memory by unearthing disappearing history. His recent work includes A Disaster Begins, about one woman’s bond with the hurricane of 1900 in Galveston, Texas, and In This Place…, inspired by the first free African-Americans to build their own home in Lexington, Kentucky. Ain is a visiting artist at the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, artist-In-residence at the Center for Creative Research and co-director of the Pick Up Performance Co(s). He first came to Marlboro as part of the Embodied Learning Symposium in April (Potash Hill, Summer 2011).

Brenda Foley is professor of theater and author of Undressed for Success: Beauty Contestants and Exotic Dancers as Merchants of Morality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). Her research interests are in performance studies, pop culture, feminism, contemporary theater and disability studies.

Carol Hendrickson is professor of anthropology and author of Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemala Town (University of Texas Press, 1995). She co-wrote Tecpán Guatemala: A Modern Maya Town in Global and Local Context (Westview, 2002) with Edward Fischer.

Kate Ratcliff is professor of American studies at Marlboro, where her teaching ranges from the Federalist Papers to post–World War II television sitcoms. She recently joined the board of the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences and participated in a panel on Vermont history at the fall conference.

Made in and around Vermont

“Anyone who studies colonial America will quickly realize that no part of our history, and no geographic area, is a vacuum,” said senior Alex Tolstoi. “Everything affects everything.” For his Plan of Concentration, Alex is examining the social and political influences of neighboring colonies on 18th-century Vermont, drawing in part on historic captivity narratives. By learning about differing social and economic structures of colonial New England and New York, Alex plans to show how leaders in the Green Mountain region created a Vermont identity and raised support for an independent Republic of Vermont. “This Republic had one of the first constitutions to outlaw slavery, had no landownership requirement for suffrage and became involved in an international affair over the possibility of rejoining the English Empire.”

“Anyone who studies colonial America will quickly realize that no part of our history, and no geographic area, is a vacuum,” said senior Alex Tolstoi. “Everything affects everything.” For his Plan of Concentration, Alex is examining the social and political influences of neighboring colonies on 18th-century Vermont, drawing in part on historic captivity narratives. By learning about differing social and economic structures of colonial New England and New York, Alex plans to show how leaders in the Green Mountain region created a Vermont identity and raised support for an independent Republic of Vermont. “This Republic had one of the first constitutions to outlaw slavery, had no landownership requirement for suffrage and became involved in an international affair over the possibility of rejoining the English Empire.”

Tough Love in the Garden State

By Molly MacLeod ’08

Most people might not think of New Jersey first and foremost as an epicenter of pollinator conservation, but alumna ecologist Molly MacLeod is learning to appreciate the Garden State one bee at a time.

I live in a state that’s known for its superlative population density. But much of New Jersey’s human-dominated land area is in fact a mosaic of farmland and semi-natural habitat, along with nature preserves in the Pine Barrens, the Jersey Shore and the Delaware Water Gap. The presence of these habitat types tempers the state’s dense human settlement, and the fact that they occur within the same landscape as agricultural crops means that New Jersey is prime real estate for the conservation of species that are both threatened by and supportive of human expansion.

The species I am talking about are bees, the obligate flower-feeders of the insect world. Bees are not only devoted workhorses that drink (nectar) on the job, but they are also, incidentally, crucial messengers of information between flowers. Bees go to flowers to get food, and in the process they transfer pollen from male to female flower parts, which results in fruits, seeds and future offspring. Recent studies estimate that 85 percent of the world’s plant species and 75 percent of the world’s crops are pollinated by animals, and bees are the primary animals that do the job. Surprisingly, New Jersey’s diversity of habitats supports an estimated 400 native, wild bee species, which makes it a great place to study both pollination ecology and biodiversity conservation.

Because of dramatic evidence of pollinator declines in some regions of the world, landowners, policy makers and the public have been turning their attention to protecting and restoring native bees. The USDA supports this endeavor through the 2008 version of the Farm Bill, which provides billions of dollars for habitat restoration on agricultural lands, with the explicit mention of pollinators as a restoration target. But in a classic case of the cart before the horse, the funding is for the restoration itself, not for the research to inform it. I hope to contribute to this research through my doctoral project, a dose of “tough love” focused on identifying specific ways to restore native pollinators on agricultural land.

Before we can address the how, we need to address the which, as in identifying which of the 400 bee species need restoration. This puts us directly in the center of a decades-long tug-of-war between two schools of conservation biology: Do we save a species for its own sake? Or, more pragmatically, do we save it for what it gives to us? Through an analysis I did in my first year at Rutgers, I’ve found that some of these species (in fact, only 12) are highly abundant visitors to crop plants. I call these the key ecosystem service-providers. This means that these bee species fill a functional role in the ecosystem that is valuable to humans, and they do it for “free,” unlike managed species like the honey bee. Because these species are so abundant on crops relative to other bee species, they have a disproportionate impact on the pollination of economically important plants. They are thus an important conservation target, even though they are in no immediate danger of extinction. This is the rationale behind the ecosystem services approach to conservation—the protection of the “natural capital” that ecosystems provide to humans.

Before we can address the how, we need to address the which, as in identifying which of the 400 bee species need restoration. This puts us directly in the center of a decades-long tug-of-war between two schools of conservation biology: Do we save a species for its own sake? Or, more pragmatically, do we save it for what it gives to us? Through an analysis I did in my first year at Rutgers, I’ve found that some of these species (in fact, only 12) are highly abundant visitors to crop plants. I call these the key ecosystem service-providers. This means that these bee species fill a functional role in the ecosystem that is valuable to humans, and they do it for “free,” unlike managed species like the honey bee. Because these species are so abundant on crops relative to other bee species, they have a disproportionate impact on the pollination of economically important plants. They are thus an important conservation target, even though they are in no immediate danger of extinction. This is the rationale behind the ecosystem services approach to conservation—the protection of the “natural capital” that ecosystems provide to humans.

In contrast, the traditional biodiversity approach to conservation would prioritize the protection of rare species, independent of human needs but instead based on ethical or scientific arguments of intrinsic value. Many of the hundreds of wild, native bee species in New Jersey are relatively rare, making it more difficult to obtain data on their natural history and population trends and to effectively conserve them. We do know, however, that some of these rare species specialize on particular plant species. For example, one species of solitary bee in the genus Andrena is an azalea specialist—due to the arrangement of this bee species’ pollen-collecting hairs, it is one of the few Andrena that can handle Rhododendron pollen. There’s also a type of small, dark sweat bee in the genus Lasioglossum that specializes on evening primrose, Oenothera.

Theoretically, we should be able to support the restoration of those rare bees by establishing their host plants. But we have little evidence to prove that this is actually the case in practice. Agricultural restorations in northwest Europe have shown little to no effect on rare pollinator species that scientists are worried about conserving, while common, “weedy” bee species increased as a result of the plantings. But many of the rare pollinators are not likely to be found in those intensively used landscapes in the first place. Would the same be true for New Jersey, where the landscape is generally supportive of diverse native bees?

My project is designed to address these issues in two stages. Stage one is to identify the native plant species that are preferred by bee pollinators in general and by the rare or key-crop pollinating bees in my two target groups. Historically, “good bee plants” have been recommended based on anecdotal observations or on an oversimplified set of assumptions about coevolution based on the shapes of flowers and their bee visitors. But plant-pollinator relationships in nature are not actually so prescribed; these recommendations don’t account for the fact that a highly abundant plant species may appear to be a favorite among bees compared to other species blooming at the same time, simply due to its abundance. Bees want food and, like all of us, they may be willing to compromise quality for convenience—take less desirable pollen from a nearby plant rather than fly farther for higher quality food. This is one way in which field observations can bias the true preference a bee species has for a certain plant. Will the rare, specialist bees be attracted to the same plants that the more abundant, generalist bees prefer? If so, then the same plant species could be used to restore rare bees and support key-crop pollinators.

To answer this question, I worked from April to September last year at a U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service site near Cape May, New Jersey, observing an experimental bee buffet. At this site I had a field full of 26 native plant species, each planted in multiple, one-square-meter, single-species plots. The plants were chosen for this study because they were known to be generally attractive to pollinators but had not been compared with each other in a controlled setting or evaluated for their ease of cultivation. To assess the attractiveness of each plant species, I net-captured all of the flower visitors to each plot on four separate days during that plot’s peak bloom. It’s possible to identify some bees “on the wing,” but to know exactly which bees in my target groups are visiting these plants, I had to net-collect them and bring them back to the lab for identification.

To answer this question, I worked from April to September last year at a U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service site near Cape May, New Jersey, observing an experimental bee buffet. At this site I had a field full of 26 native plant species, each planted in multiple, one-square-meter, single-species plots. The plants were chosen for this study because they were known to be generally attractive to pollinators but had not been compared with each other in a controlled setting or evaluated for their ease of cultivation. To assess the attractiveness of each plant species, I net-captured all of the flower visitors to each plot on four separate days during that plot’s peak bloom. It’s possible to identify some bees “on the wing,” but to know exactly which bees in my target groups are visiting these plants, I had to net-collect them and bring them back to the lab for identification.

Once I have all of my bees identified, I’ll rank the plants by their attractiveness based on the totals of bee abundance and diversity per species. But it wouldn’t be fair to compare a spring-blooming plant like Penstemon with a late-summer-blooming goldenrod, because the abundance and identity of bees between those times of the year are markedly different, so I’ll compare early-, mid- and late-blooming plants separately. In 2010, the first year data were collected, nine plant species were ranked as most attractive. For 2011, I’ll see whether I get the same results from more-established plants. But the real litmus test will be to see how these plants stack up next to existing restorations that were established without the bee preference data I’m collecting. This broader context will be stage two of my thesis work. Will targeted plantings using my most attractive species restore those key bee groups more effectively than previous restoration efforts? I’ll test this idea by establishing mixed-species plots in six separate sites across New Jersey. Each site will also contain an existing restoration plot and an unrestored control—an area that best represents the site’s conditions before any restoration took place. I’ll compare bee visitation to these plots over the next few years to better understand whether our current restorations are making a dent and how to better tailor them for the species that need it most.

Answering these questions would ensure that the Farm Bill funding is effective both for rare species and for species that play a key economic role in crop production. Support for insect conservation is practically nonexistent outside of this bill, due in part to a lack of biological information on most species necessary for informed, targeted conservation plans. Certainly, this lack of funding is also due to the fact that many insects are given a bad rap because of some species that are considered noxious or aggressive. Meanwhile, the tug-of-war between saving species for their own sake and saving them for more selfserving reasons makes it difficult to know where to start. Can we therefore take what little funding we have, and dovetail these divergent conservation goals? I hope so. The business of a successful restoration lies in thrifty diplomacy, and in practice it depends on a balance between well-informed risks and leaps of faith. Striking that balance is where the tough love comes in—the faith that the right connections can be made, the knowledge that they won’t just make themselves and the willingness to work for them. In the case of pollinators, we need to make that first, deliberate move.

Molly MacLeod graduated from Marlboro in 2008 with a Plan of Concentration in ecology and conservation, including a project on pollination in forest patches. She is continuing her research on pollination while pursuing a doctoral degree in ecology and evolution at Rutgers University.

Pollination Deviation

Most of us are familiar with the idea of bees visiting flowers, but pollinators can take more unusual forms, such as lizards, rodents and primates. For her Plan of Concentration, senior Joella Simons Adkins is focusing on one group of nonconventional pollinators known as “non-flying mammals,” a.k.a. mammals other than bats. “It has been found that non-flying mammals, mainly rodents and elephant shrews, pollinate many species in the flowering plant family Proteaceae in South Africa and Australia,” said Joella. “Specialized floral traits found in South African Protea species include robust flowers situated at ground level, dull coloration, a strong yeasty odor and copious amounts of nectar that is available at night when the rodents are active.” Protea species in Australia, on the other hand, have more generalized flowers and a wider range of visitors, including birds, insects and mammals.

Most of us are familiar with the idea of bees visiting flowers, but pollinators can take more unusual forms, such as lizards, rodents and primates. For her Plan of Concentration, senior Joella Simons Adkins is focusing on one group of nonconventional pollinators known as “non-flying mammals,” a.k.a. mammals other than bats. “It has been found that non-flying mammals, mainly rodents and elephant shrews, pollinate many species in the flowering plant family Proteaceae in South Africa and Australia,” said Joella. “Specialized floral traits found in South African Protea species include robust flowers situated at ground level, dull coloration, a strong yeasty odor and copious amounts of nectar that is available at night when the rodents are active.” Protea species in Australia, on the other hand, have more generalized flowers and a wider range of visitors, including birds, insects and mammals.

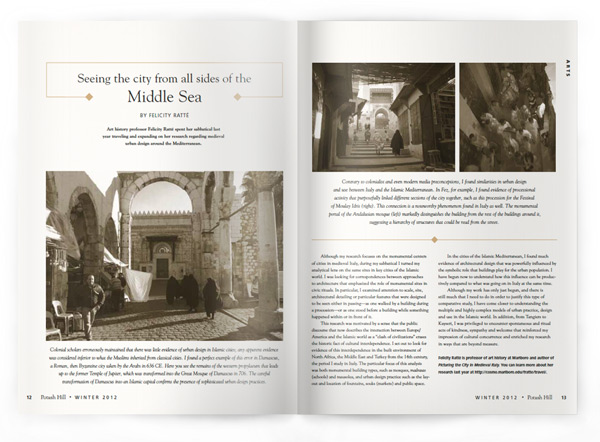

Seeing the city from all sides of the Middle Sea

By Felicity Ratté

Art history professor Felicity Ratté spent her sabbatical last year traveling and expanding on her research regarding medieval urban design around the Mediterranean.

Although my research focuses on the monumental centers of cities in medieval Italy, during my sabbatical I turned my analytical lens on the same sites in key cities of the Islamic world. I was looking for correspondences between approaches to architecture that emphasized the role of monumental sites in civic rituals. In particular, I examined attention to scale, site, architectural detailing or particular features that were designed to be seen either in passing—as one walked by a building during a procession—or as one stood before a building while something happened within or in front of it.

This research was motivated by a sense that the public discourse that now describes the interaction between Europe/America and the Islamic world as a “clash of civilizations” erases the historic fact of cultural interdependence. I set out to look for evidence of this interdependence in the built environment of North Africa, the Middle East and Turkey from the 14th century, the period I study in Italy. The particular focus of this analysis was both monumental building types, such as mosques, madrasas (schools) and mausolea, and urban design practice such as the layout and location of fountains, souks (markets) and public space.

In the cities of the Islamic Mediterranean, I found much evidence of architectural design that was powerfully influenced by the symbolic role that buildings play for the urban population. I have begun now to understand how this influence can be productively compared to what was going on in Italy at the same time.

Although my work has only just begun, and there is still much that I need to do in order to justify this type of comparative study, I have come closer to understanding the multiple and highly complex models of urban practice, design and use in the Islamic world. In addition, from Tangiers to Kayseri, I was privileged to encounter spontaneous and ritual acts of kindness, sympathy and welcome that reinforced my impression of cultural concurrence and enriched my research in ways that are beyond measure.

Colonial scholars erroneously maintained that there was little evidence of urban design in Islamic cities; any apparent evidence was considered inferior to what the Muslims inherited from classical cities. I found a perfect example of this error in Damascus, a Roman, then Byzantine city taken by the Arabs in 636 CE. Here you see the remains of the western propylaeum that leads up to the former Temple of Jupiter, which was transformed into the Great Mosque of Damascus in 706. The careful transformation of Damascus into an Islamic capital confirms the presence of sophisticated urban design practices.

Colonial scholars erroneously maintained that there was little evidence of urban design in Islamic cities; any apparent evidence was considered inferior to what the Muslims inherited from classical cities. I found a perfect example of this error in Damascus, a Roman, then Byzantine city taken by the Arabs in 636 CE. Here you see the remains of the western propylaeum that leads up to the former Temple of Jupiter, which was transformed into the Great Mosque of Damascus in 706. The careful transformation of Damascus into an Islamic capital confirms the presence of sophisticated urban design practices.

Contrary to colonialist and even modern media preconceptions, I found similarities in urban design and use between Italy and the Islamic Mediterranean. In Fez, for example, I found evidence of processional activity that purposefully linked different sections of the city together, such as this procession for the Festival of Moulay Idris (below). This connection is a noteworthy phenomenon found in Italy as well. The monumental portal of the Andalusian mosque (above) markedly distinguishes the building from the rest of the buildings around it, suggesting a hierarchy of structures that could be read from the street.

Contrary to colonialist and even modern media preconceptions, I found similarities in urban design and use between Italy and the Islamic Mediterranean. In Fez, for example, I found evidence of processional activity that purposefully linked different sections of the city together, such as this procession for the Festival of Moulay Idris (below). This connection is a noteworthy phenomenon found in Italy as well. The monumental portal of the Andalusian mosque (above) markedly distinguishes the building from the rest of the buildings around it, suggesting a hierarchy of structures that could be read from the street.

I found some architectural details of Islamic cities that were very different from what existed in Italy. For example, a very interesting feature common to many of the cities I studied is interior gates, such as the examples here from Fez (above) and Tunis (below). These gates could be closed to reroute traffic or for enhanced security. Despite these differences, however, the principles of urban iconography—the style of built elements as well as their siting—are strikingly similar to those found in medieval cities of Italy.

I found some architectural details of Islamic cities that were very different from what existed in Italy. For example, a very interesting feature common to many of the cities I studied is interior gates, such as the examples here from Fez (above) and Tunis (below). These gates could be closed to reroute traffic or for enhanced security. Despite these differences, however, the principles of urban iconography—the style of built elements as well as their siting—are strikingly similar to those found in medieval cities of Italy.

The city in which I found the most, and most remarkable, correspondences with what I know of in Florence was Cairo, historic capital of the Mamluk dynasty. Here you can see, for example, the similarities between Cairo’s Bayn al Qasrayn (above) and Florence’s Piazza della Signoria (below). Monumental architectural complexes in Cairo, such as the mosque, madrasa and mausoleum of Sultan Qalawun (c. 1284), were designed as backdrops to civic rituals, just as churches and public palaces were in Florence.

The city in which I found the most, and most remarkable, correspondences with what I know of in Florence was Cairo, historic capital of the Mamluk dynasty. Here you can see, for example, the similarities between Cairo’s Bayn al Qasrayn (above) and Florence’s Piazza della Signoria (below). Monumental architectural complexes in Cairo, such as the mosque, madrasa and mausoleum of Sultan Qalawun (c. 1284), were designed as backdrops to civic rituals, just as churches and public palaces were in Florence.

Although the historic context for urban design and subsequent history in Anatolia is quite different from that in North Africa and the Levant, there were consistencies in how buildings were used symbolically. For example, the portal of the Sifaiye Madrasa, a Seljuk building built in c.1217, was literally overshadowed by the larger Cifte Minerali Madrasa across the street, built later by Mongol rulers when they took control of Sivas in the 1270s. This is a terrific example of how power politics played out in stone, and is reminiscent of the competition between buildings in medieval Italy.

Although the historic context for urban design and subsequent history in Anatolia is quite different from that in North Africa and the Levant, there were consistencies in how buildings were used symbolically. For example, the portal of the Sifaiye Madrasa, a Seljuk building built in c.1217, was literally overshadowed by the larger Cifte Minerali Madrasa across the street, built later by Mongol rulers when they took control of Sivas in the 1270s. This is a terrific example of how power politics played out in stone, and is reminiscent of the competition between buildings in medieval Italy.

Felicity Ratté is professor of art history at Marlboro and author of Picturing the City in Medieval Italy. You can learn more about her research last year at http://cosmo.marlboro.edu/fratte/travel/.

Reconstructing Balkan Heritage

Just when Felicity was winding down her travels, senior Colby Silver received a summer research grant for several weeks of fieldwork in Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Dalmatia. In this region ravaged by war in the 1990s, Colby documented the destruction of architectural heritage and subsequent efforts to reconstruct and conserve historic buildings and sites. “Sadly, the use of heritage often does not become perceptible to the general population until it is lost or at risk of disappearing,” said Colby. His Plan of Concentration focuses on sites significant to specific communities, such as Ottoman mosques and Serbian monasteries, which were often targeted during the war. “Given the complex interwoven fabric of religious and ethnic groups in the Balkans, the region presents a particularly poignant and varied example of heritage valuation and loss.”

Just when Felicity was winding down her travels, senior Colby Silver received a summer research grant for several weeks of fieldwork in Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Dalmatia. In this region ravaged by war in the 1990s, Colby documented the destruction of architectural heritage and subsequent efforts to reconstruct and conserve historic buildings and sites. “Sadly, the use of heritage often does not become perceptible to the general population until it is lost or at risk of disappearing,” said Colby. His Plan of Concentration focuses on sites significant to specific communities, such as Ottoman mosques and Serbian monasteries, which were often targeted during the war. “Given the complex interwoven fabric of religious and ethnic groups in the Balkans, the region presents a particularly poignant and varied example of heritage valuation and loss.”

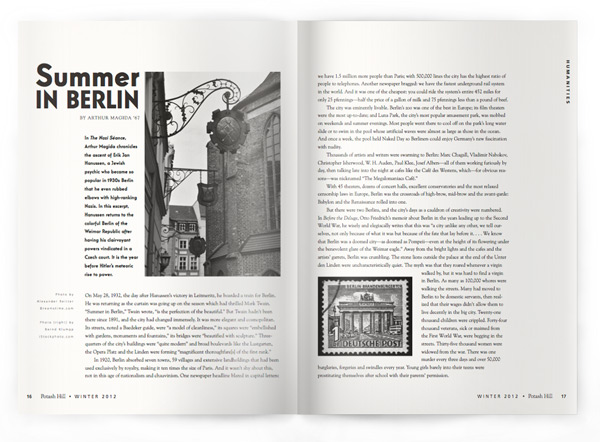

Summer in Berlin

By Arthur Magida ’67

In The Nazi Séance, Arthur Magida chronicles the ascent of Erik Jan Hanussen, a Jewish psychic who became so popular in 1930s Berlin that he even rubbed elbows with high-ranking Nazis. In this excerpt, Hanussen returns to the colorful Berlin of the Weimar Republic after having his clairvoyant powers vindicated in a Czech court. It is the year before Hitler’s meteoric rise to power.

On May 28, 1932, the day after Hanussen’s victory in Leitmeritz, he boarded a train for Berlin. He was returning as the curtain was going up on the season which had thrilled Mark Twain. “Summer in Berlin,” Twain wrote, “is the perfection of the beautiful.” But Twain hadn’t been there since 1891, and the city had changed immensely. It was more elegant and cosmopolitan. Its streets, noted a Baedeker guide, were “a model of cleanliness,” its squares were “embellished with gardens, monuments and fountains,” its bridges were “beautified with sculpture.” Three quarters of the city’s buildings were “quite modern” and broad boulevards like the Lustgarten, the Opera Platz and the Linden were forming “magnificent thoroughfare[s] of the first rank.”

In 1920, Berlin absorbed seven towns, 59 villages and extensive landholdings that had been used exclusively by royalty, making it ten times the size of Paris. And it wasn’t shy about this, not in this age of nationalism and chauvinism. One newspaper headline blared in capital letters: we have 1.5 million more people than Paris; with 500,000 lines the city has the highest ratio of people to telephones. Another newspaper bragged: we have the fastest underground rail system in the world. And it was one of the cheapest: you could ride the system’s entire 452 miles for only 25 pfennings—half the price of a gallon of milk and 75 pfennings less than a pound of beef.

The city was eminently livable. Berlin’s zoo was one of the best in Europe; its film theaters were the most up-to-date; and Luna Park, the city’s most popular amusement park, was mobbed on weekends and summer evenings. Most people went there to cool off on the park’s long water slide or to swim in the pool whose artificial waves were almost as large as those in the ocean. And once a week, the pool held Naked Day so Berliners could enjoy Germany’s new fascination with nudity.

The city was eminently livable. Berlin’s zoo was one of the best in Europe; its film theaters were the most up-to-date; and Luna Park, the city’s most popular amusement park, was mobbed on weekends and summer evenings. Most people went there to cool off on the park’s long water slide or to swim in the pool whose artificial waves were almost as large as those in the ocean. And once a week, the pool held Naked Day so Berliners could enjoy Germany’s new fascination with nudity.

Thousands of artists and writers were swarming to Berlin: Marc Chagall, Vladimir Nabokov, Christopher Isherwood, W. H. Auden, Paul Klee, Josef Albers—all of them working furiously by day, then talking late into the night at cafes like the Café des Westens, which—for obvious reasons—was nicknamed “The Megalomaniacs Café.”

With 45 theaters, dozens of concert halls, excellent conservatories and the most relaxed censorship laws in Europe, Berlin was the crossroads of high-brow, mid-brow and the avant-garde: Babylon and the Renaissance rolled into one.

But there were two Berlins, and the city’s days as a cauldron of creativity were numbered. In Before the Deluge, Otto Friedrich’s memoir about Berlin in the years leading up to the Second World War, he wisely and elegiacally writes that this was “a city unlike any other, we tell ourselves, not only because of what it was but because of the fate that lay before it. . . . We know that Berlin was a doomed city—as doomed as Pompeii—even at the height of its flowering under the benevolent glare of the Weimar eagle.” Away from the bright lights and the cafes and the artists’ garrets, Berlin was crumbling. The stone lions outside the palace at the end of the Unter den Linden were uncharacteristically quiet. The myth was that they roared whenever a virgin walked by, but it was hard to find a virgin

in Berlin. As many as 100,000 whores were walking the streets. Many had moved to Berlin to be domestic servants, then realized that their wages didn’t allow them to live decently in the big city. Twenty-one thousand children were crippled. Forty-four thousand veterans, sick or maimed from the First World War, were begging in the streets. Thirty-five thousand women were widowed from the war. There was one murder every three days and over 50,000 burglaries, forgeries and swindles every year. Young girls barely into their teens were prostituting themselves after school with their parents’ permission.

in Berlin. As many as 100,000 whores were walking the streets. Many had moved to Berlin to be domestic servants, then realized that their wages didn’t allow them to live decently in the big city. Twenty-one thousand children were crippled. Forty-four thousand veterans, sick or maimed from the First World War, were begging in the streets. Thirty-five thousand women were widowed from the war. There was one murder every three days and over 50,000 burglaries, forgeries and swindles every year. Young girls barely into their teens were prostituting themselves after school with their parents’ permission.

The slums of Chicago, the gangsters of New York, the sorrows of Dickens’ London had descended on Berlin. Away from the late night discussions about art and politics and philosophy, Berlin was a symphony of pain. Inflation was so bad that housewives burned their worthless paper currency to heat their homes. One egg cost as much as 30 million eggs before the war. Almost every day, one more person used their entire savings for a tram ride to the other side of the city, where they threw themselves off a bridge. When Wall Street collapsed in 1929 and the Americans called in their German loans, unemployment tripled, then that number doubled. The country was tottering, torn between democrats, Communists and fascists, and Berlin, the capital, was crumbling under the never-ending and always worsening crises. New to democracy, which had begun only in 1918 when the Kaiser abdicated, the city—and the whole country—was breaking down.

This was Hanussen’s home. The cripples and the widows and the homeless didn’t know about him. If they had, they wouldn’t have cared. Life, for them, was too much of a grind. Rather, his audience was the people who enjoyed theater and spectacle and the avant-garde. And of course, much of his following would come from the same people who were attracted to the seers and the fortunetellers who had swarmed to Berlin after the armistice. Once the war was over, reason was given a vacation. The mind could think its way out of only so much misery. Throughout Europe, the lamentations for the dead and the maimed were loud. They were louder in Berlin, which is why so many practitioners of the psychic arts—20,000 by one count, up from 600 in 1900—flocked here. Hanussen knew this was his moment. What better place for him than Berlin, city of glitter, glitz and sorrow? Hanussen was many things, but he was never cautious. The troops from the right and the left were lining up. Hanussen didn’t care about that. He had left Leitmeritz a hero. It was time, he was sure, for the city to line up before him.

From The Nazi Séance by Arthur J. Magida. Copyright © 2011 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Arthur Magida is writer-in-residence at the University of Baltimore and a journalism professor at Georgetown University. His books, including The Rabbi and the Hit Man and Prophet of Rage: A Life of Louis Farrakhan and His Nation, can be found at www.arthurmagida.com.

The Art of Folkishness

Long before the extreme nationalism of the Third Reich, there was the more benign nationalism of the German folk movement in the early 19th century. For her Plan of Concentration in music, senior Rebecca Gildea is exploring the concept of “the folk” in German history, with all its nationalistic associations and impacts on music. “There are so many qualities and hidden meanings that are assumed when we talk about folk music, and those change every time you consider a different kind of folk music, whether ‘African,’ or ‘American,’ or ‘Hungarian,’” said Rebecca. “My Plan follows where these qualities and assumptions come from during the early folk movement in Germany, and how they were expressed and elaborated on in music.”

Gorilla Morality

By Kathryn Lyon ’13

Illustration by Evan Lorenzen ’13

Suppose you were to come across a human and an ape dangling from the side of a cliff. The two are of arguably equal intelligence and have an equal capacity for suffering. You might correctly assess that both creatures have the same interest in being alive. This being said, how do you choose which being to save, or which to save first? Which choice is morally correct? These questions concern not morality in general, but rather our moral obligations to animals.

Morality is a human notion. Despite this, some animal rights advocates argue for moral laws across the animal kingdom. Martha Nussbaum, for example, proposes “the gradual formation of an interdependent world in which all species will enjoy cooperative and mutually supportive relations with one another.” Apparently, she suggests replacing what is natural with what she views as just. But Nussbaum disregards the fact that animals have no concept of morality themselves.

For example, a lion does not take a gazelle’s interests into perspective before attacking it. Peter Singer, author of All Animals Are Equal, might claim that the lion is acting “speciesist”—allowing the interests of its own species to override the greater interests of other species. Singer would view it as our human duty to interfere on behalf of the gazelle, ensuring that both animals’ interests are equally considered. But only by human standards could putting one’s own species above others ever be seen as wrong; every other species on the planet puts its own interests first. So while theories of animal morality determine appropriate human treatment of animals, they cannot regulate interaction between other animal species.

Because we are human we value human life above animal life, and thus our survival above theirs; we hold our own interests above those of other animals. If we were to consider only our own interests, “morality” would not even enter into the equation. The more comfortable we are within our lifestyles, however, the more apt we are to establish rules and regulations regarding morality or ethics. Because we are not directly competing with other species for survival, we can take their interests into account. In doing so, I believe we have the responsibility to recognize that we cannot cause animals to suffer in exchange for mere human wants.

Because we are human we value human life above animal life, and thus our survival above theirs; we hold our own interests above those of other animals. If we were to consider only our own interests, “morality” would not even enter into the equation. The more comfortable we are within our lifestyles, however, the more apt we are to establish rules and regulations regarding morality or ethics. Because we are not directly competing with other species for survival, we can take their interests into account. In doing so, I believe we have the responsibility to recognize that we cannot cause animals to suffer in exchange for mere human wants.

Every sentient being has an interest in avoiding pain. I maintain that their interests should not be compromised for anything less than the human interest in avoiding pain. Thus, harmful practices that do not alleviate human pain and suffering, such as the use of animals in the entertainment industry or for cosmetics testing, are not morally justified. Regarding animals as test subjects for medical research, human bias dictates that they should be used before we use members of our own species—but only in situations where researching upon a human would also be justified. In other words, while the discriminatory practice of testing on animals before humans is not immoral, unnecessary harm to sentient animals is.

Similarly, while consuming animals is not inherently immoral, if we have the means to survive as vegetarians, we have the moral responsibility to avoid killing animals for food out of respect for their lives and their interests in being alive. Because we would not eat humans, we should not eat animals. However, in situations where vegetarianism is not an option, it is not immoral for people to survive by eating animals. When survival is at stake, surely it is “better” to eat an animal than a person.

Returning to the cliff-hanging scenario, it is clear that a moral, rational human would save the person first. Despite idealist theory, the obligation to our own species demands that we sacrifice the ape to save the human. Any moral code must be subjective, as it may change according to the specific situation in which it is applied. Human existence is a balance between following the most moral practices one can and surviving.

I recognize that from a universal perspective this is not “fair” to non-human animals; however, as humans we owe our loyalty to the species Homo sapiens. Human perspective is inherently biased, but it is the only perspective from which we can address this issue. It is impossible for humans to truly consider moral equality for animals when we have our own interests in survival at stake. What is immoral is for humans to hurt animals unnecessarily or kill them frivolously. Whenever the resources exist to do so, animal life or suffering must be spared. We have a moral duty to the animals of this world, but foremost we have a duty to our species.

Kathryn Lyon is a sophomore at Marlboro and winner of last year’s Freshman/Sophomore Essay Prize, awarded each year for the best essay written for any course. This article is adapted from her essay, “Animal Morality in Concentric Circles,” written for her Environmental Philosophy class.

On & Off the Hill

Learn about new faculty members, a journey to Cambodia, responses to Tropical Storm Irene, events in theater and film, notable students, faculty and staff, and more. Marlboro community members are everywhere.

Learn about new faculty members, a journey to Cambodia, responses to Tropical Storm Irene, events in theater and film, notable students, faculty and staff, and more. Marlboro community members are everywhere.

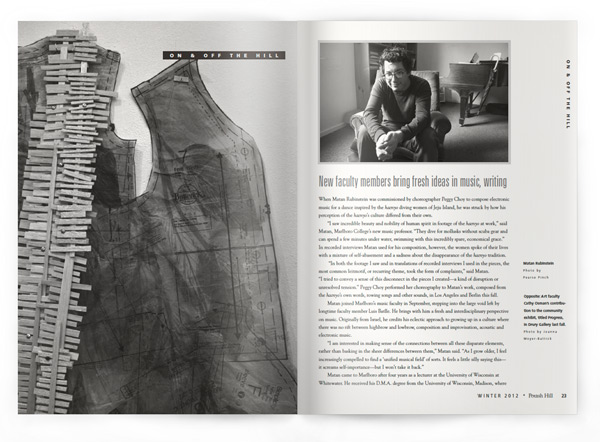

New faculty members bring fresh ideas in music, writing

When Matan Rubinstein was commissioned by choreographer Peggy Choy to compose electronic music for a dance inspired by the haenyo diving women of Jeju Island, he was struck by how his perception of the haenyo’s culture differed from their own.

“I saw incredible beauty and nobility of human spirit in footage of the haenyo at work,” said Matan, Marlboro College’s new music professor. “They dive for mollusks without scuba gear and can spend a few minutes under water, swimming with this incredibly spare, economical grace.” In recorded interviews Matan used for his composition, however, the women spoke of their lives with a mixture of self-abasement and a sadness about the disappearance of the haenyo tradition.

“In both the footage I saw and in translations of recorded interviews I used in the pieces, the most common leitmotif, or recurring theme, took the form of complaints,” said Matan. “I tried to convey a sense of this disconnect in the pieces I created—a kind of disruption or unresolved tension.” Peggy Choy performed her choreography to Matan’s work, composed from the haenyo’s own words, rowing songs and other sounds, in Los Angeles and Berlin this fall.

Matan joined Marlboro’s music faculty in September, stepping into the large void left by longtime faculty member Luis Batlle. He brings with him a fresh and interdisciplinary perspective on music. Originally from Israel, he credits his eclectic approach to growing up in a culture where there was no rift between highbrow and lowbrow, composition and improvisation, acoustic and electronic music.

“I am interested in making sense of the connections between all these disparate elements, rather than basking in the sheer differences between them,” Matan said. “As I grow older, I feel increasingly compelled to find a ‘unified musical field’ of sorts. It feels a little silly saying this—it screams self-importance—but I won’t take it back.”

Matan came to Marlboro after four years as a lecturer at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater. He received his D.M.A. degree from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where his dissertation piece was a composition for electronic sound and large chamber ensemble entitled Le Invisibili. This work, a modular piece comprising 35 musical segments that can be combined 27,300 ways, was the culmination of a decade of creating musical compositions that can be radically different with every performance.

Matan came to Marlboro after four years as a lecturer at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater. He received his D.M.A. degree from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where his dissertation piece was a composition for electronic sound and large chamber ensemble entitled Le Invisibili. This work, a modular piece comprising 35 musical segments that can be combined 27,300 ways, was the culmination of a decade of creating musical compositions that can be radically different with every performance.

Matan brings a wide range of talents and experiences to Marlboro and is a prolific composer of music that is diverse in practice, medium and method. He is a frequent collaborator with artists in other disciplines, and he often makes music for dance and film. Some recent examples include Palimpsest for trombone and “tape,” commissioned by trombonist Michael Dugan; Knotcracker, commissioned by the Li Chiao-Ping Dance Company; and the score for Verge, a dance film directed by Douglas Rosenber. Matan is an active performer, having founded both the Sada Jazz Trio and the Modular Music Ensemble, and has several recordings to his credit. He is also a passionate teacher with interests that span many disciplines.

“Teaching music is the best way I know of to prove the infinite ways in which people conceive of and hear music,” he said. “Every time I teach a piece of music, someone brings a distinctly different way of hearing it. I can never be bored with my vocation this way.”

Marlboro’s interdisciplinary approach similarly resonates with new writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard. “When I saw the titles of recent Marlboro course offerings and student Plans, I was amazed at how diverse and vibrant the academics were,” said Kyhl, who also joined the community in September. “My initial pleasure in learning about Marlboro gave rise to a strong desire to be amidst those catalog listings. This was a chance to challenge disciplinary boundaries on a daily basis and join a community that is built around flexibility of inquiry.”

Kyhl came to Marlboro from Luther College, in Iowa, where he spent a year as an Associated Colleges of the Midwest–Mellon postdoctoral fellow in English and environmental studies. He received his Ph.D. in English with an emphasis in literature and environment from the University of Nevada at Reno. His dissertation, titled “Landscape of Removal and Renewal: Cross-Cultural Resistance in 19th-Century American Captivity Narratives,” is currently under review by the University of Oklahoma Press. It examines a handful of subversive Indian captivity narratives published in the 1820s and 1830s that challenge Indian Relocation Act policies and depict the frontier wilderness as a domestic and inhabited space. Kyhl also co-edited an anthology entitled Currents of the Universal Being: Explorations in the Literature of Energy, which had its genesis in a student seminar, forthcoming from Texas Tech University Press. He has written many articles and chapters on literature, writing pedagogy and the natural world, as well as reviews, nonfiction and poetry.

Kyhl came to Marlboro from Luther College, in Iowa, where he spent a year as an Associated Colleges of the Midwest–Mellon postdoctoral fellow in English and environmental studies. He received his Ph.D. in English with an emphasis in literature and environment from the University of Nevada at Reno. His dissertation, titled “Landscape of Removal and Renewal: Cross-Cultural Resistance in 19th-Century American Captivity Narratives,” is currently under review by the University of Oklahoma Press. It examines a handful of subversive Indian captivity narratives published in the 1820s and 1830s that challenge Indian Relocation Act policies and depict the frontier wilderness as a domestic and inhabited space. Kyhl also co-edited an anthology entitled Currents of the Universal Being: Explorations in the Literature of Energy, which had its genesis in a student seminar, forthcoming from Texas Tech University Press. He has written many articles and chapters on literature, writing pedagogy and the natural world, as well as reviews, nonfiction and poetry.

“An essay I’m planning to read at a conference in Alaska next summer will somehow combine Hurricane Irene, Thoreau’s Maine Woods, climate change and ideas of freedom and community in early and present-day America,” said Kyhl. “This list of topics suggests that Marlboro’s interdisciplinary approach to academics has influenced me already.”

Kyhl believes that good writing depends on confidence and the freedom to speak your own mind, and he creates a classroom environment that fosters a sense of personal responsibility

“Individuality in thought and expression is all too rare and undervalued these days, and I can’t imagine working anywhere but a small liberal arts college,” he said. “Marlboro’s small size is a real asset in forging the sorts of alliances and creative solutions needed to offer flexibility in student tutorials and Plans.”

Kyhl’s choices in course readings often emphasize literature that has inspired action. Dan Phillippon’s Conserving Words, for example, traces how nature writers have directly influenced the creation of environmental groups, as in the case of John Muir and the Sierra Club or Mabel Osgood Wright and the Audubon Society. “Teaching literature that has had direct and often measurable influences on policy and public attitudes shows students the power of language,” Kyhl said.

Both Kyhl and Matan are already active participants in the Marlboro community. Matan jumped immediately into participating in Town Meeting, giving the traditional annual plea for driving carefully on South Road, and played Copland and Gershwin processionals for Convocation. Kyhl led a group of students to do hurricane relief work for Marlboro residents on Augur Hole Road, and hit the go-ahead home run in the faculty-student softball game. The community welcomes these additions, and looks forward to their many and varied contributions to come.

Marlboro Returns to Cambodia

Last May, Marlboro community members took part in the second service-learning trip to Cambodia in the past three years, building on relationships from the last visit and forging new ones. For two weeks, art faculty John Willis and Cathy Osman as well as Max Foldeak, director of health services, were joined by seven students as they visited communities, participated in ESL classes in local schools and helped with water projects.

Last May, Marlboro community members took part in the second service-learning trip to Cambodia in the past three years, building on relationships from the last visit and forging new ones. For two weeks, art faculty John Willis and Cathy Osman as well as Max Foldeak, director of health services, were joined by seven students as they visited communities, participated in ESL classes in local schools and helped with water projects.

“Going to Cambodia completely changed the way I look at the world, and specifically the way I look at America,” said senior Nick Rouke. “It was the first time I had left the country, and it was incredibly difficult. It made me realize what I take for granted.”

Before their trip, the group initiated a community-wide auction of paintings, prints, photos, books, ceramics and other artwork created by students and faculty to raise $2,500 in aid for organizations in Cambodia. They also brought children’s books, medications and medical equipment, including nearly a thousand pairs of eyeglasses, donated from many local sources, as well as 30 laptop computers donated by Pfizer, Inc. Donations were processed through the World Peace Fund and the Amherst/Cambodia Water project. In-kind donations were brought by the group directly to schools in Kampong Chhnang, Ang, Pursat, Omani, Siem Reap and other communities where they participated in service projects.

In addition to their work in communities, the group from Marlboro visited the capital of Phnom Penh, the temples at Angkor and memorials to those killed during the Khmer Rouge period.

In addition to their work in communities, the group from Marlboro visited the capital of Phnom Penh, the temples at Angkor and memorials to those killed during the Khmer Rouge period.

“We visited Tuol Sleng, a school that Pol Pot converted into a prison where he tortured and killed people,” said Nick, who had previously studied captivity and totalitarian regimes in other contexts. “People would be killed for disagreeing, much like the purges during the Stalinist era. It was very difficult to be there, but it made me really think about the things I have studied during my time here at Marlboro, why they are important to me, and what I want to do about it.”

Marlboro responds to flood damage

The Marlboro community will not soon forget the day in late August when Tropical Storm Irene destroyed local roads and cut the college off from the rest of the world for days. But perhaps more remarkable than the college’s resilience during and after the storm was the response to neighboring communities where the flooding wreaked even more havoc.

As early as September 3, just a week after the storm, a group of 21 Marlboro students and staff participated in the United Way Day of Caring. This was an event planned long before the flooding, and most of the projects for large groups did not directly involve flood relief. However, the outpouring of support was essential to the nonprofits that provide much-needed programs in the region, and a boon to the local efforts of the United Way. Marlboro students helped scrape and paint facilities at Green Mountain Girls Camp in Dummerston, Farming Connections in Guilford and Living Memorial Park Snow Sports in Brattleboro. Several students helped at Glen Park, on Western Avenue, a mobile home park for elderly residents that was damaged by floodwaters.

“It was one of the toughest, nastiest jobs anyone has had to face,” said Christine Forbes, whose 95-year-old mother, Alice Joslin, was one of the Glen Park residents helped by students. “Not only was the job completed, but they were so pleasant to her and made the job almost fun. I will long remember the happiness in her voice when she talked about these students. They were truly extraordinary young folks.”

The following weekend, as most of the local roads became passable, Marlboro’s new writing professor, Kyhl Lyndgaard, led a group of three students and one parent of a former student to the hardest-hit road in Marlboro, Augur Hole Road. There they helped remove silt from the residence that was once the Branch Schoolhouse.

“For all of us, the storm was a new and shocking experience,” said Kyhl. “But the washed-out roads have been more than matched by the resilience of Marlboro residents.”

On September 24, more than 70 students, faculty and staff joined together at Whittemore Theater to be part of the world’s largest poetry reading, 100,000 Poets for Change, an event that brings poets and other artists together to perform simultaneously around the world. The local effort, which directly supported United Way disaster relief and benefited victims of the storm, featured readings and performances by receptionist Sunny Tappan ’77, writing professor John Sheehy, senior Gina Ruth and junior Jack Rossiter-Munley, who organized the evening. It also included a silent auction and bake sale, and altogether raised more than $700 for local flood relief efforts.

Finally, a fund drive that started as a dare between two students ended with a total donation of $5,139 for the United Way of Windham County. When senior Anna Hughes offered to pay junior Chuck Pillette to dye his hair blue, they decided to up the ante and raise money for those affected by the flooding as well as others in need. Jodi Clark ’95, director of housing and residential life, was planning the traditional employee fundraising effort for the United Way when Anna asked for help getting her campaign going.

“It simply seemed like a great way to accomplish both the employee campaign and this student-led idea by combining them to make it a whole campus community campaign,” said Jodi. The resulting “Green for Blue” fund drive involved 17 prominent community members who promised to dye their hair blue if donations reached a certain level. While the campaign raised just $500 less than the goal of $5,000—the point at which Marlboro President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell pledged to go blue—a final push by faculty and students at the graduate school brought the total above that mark.

Events feature futuristic theater, Chinese cinema

In November, the theater program presented two contemporary one-act plays by Caryl Churchill at Whittemore Theater, rounding out a full semester of events. The plays, Far Away and A Number, were directed by guest director Anna Bean, who worked with Marlboro students to present The Clean House last fall.

In November, the theater program presented two contemporary one-act plays by Caryl Churchill at Whittemore Theater, rounding out a full semester of events. The plays, Far Away and A Number, were directed by guest director Anna Bean, who worked with Marlboro students to present The Clean House last fall.

“This year I chose these two one-acts by Churchill, a British playwright whose work I find witty and chilling at the same time,” said Anna, who teaches at the Berkshire Arts and Technology Charter Public School and at Community College of Vermont in Bennington. “I saw both Far Away and A Number during their New York runs, and they have both haunted me with their tales of foreboding about the future. I thought I would see if we could create the same effect at Marlboro.”

Although both plays are set in the future, it’s a not-so-distant future that feels easily within reach. Far Away takes place in a post-apocalyptic world, where the heroine hat-maker negotiates her way, one precarious step at a time, while A Number centers around a father who made the choice long ago to clone his son.

“Both plays deal with themes of paranoia, war, fear—all of which are very present in our current culture,” said junior Kirsten Wiking, one of the students featured in the productions. Also included were sophomore Courtney Varga, sophomore Luc Rosenthal, junior Evan Lamb and freshman Luke Benning. “There’s a very real feel to the events in them, even if there are absurd elements,” continued Kirsten. “Because there’s a feeling of ‘this could be real,’ it was easy as a performer to tap into the fear or feeling of the events of the play.”

Also in November, the Asian studies program presented a weekend-long film festival titled Contemporary Landscapes of China. The six films showcased some of the best new films from China, including both features and documentaries, dealing with a range of contemporary social and environmental issues. For example, Before the Flood profiles people whose livelihoods are destroyed by the Three Gorges Dam, and Last Train Home documents the massive internal migration from China’s poorer inland provinces to the new industrial heartland. Each film was accompanied by a discussion led by authorities on the subject, including Asian studies professor Seth Harter, economics professor Jim Tober, Chinese language professor Grant Li and alumnus Tristan Roberts ’00.

For news about upcoming events, go to www.marlboro.edu/news/events.

A goddess slinks into eternity

Those who frequent the science building are missing Kali, the 13.5-foot Burmese python, who passed away in September. Kali was six feet long when she was first introduced to the college 22 years ago by science faculty John Hayes and Jenny Ramstetter, despite the misgivings of their colleague Bob Engel.

Those who frequent the science building are missing Kali, the 13.5-foot Burmese python, who passed away in September. Kali was six feet long when she was first introduced to the college 22 years ago by science faculty John Hayes and Jenny Ramstetter, despite the misgivings of their colleague Bob Engel.

“Bob’s reservations gradually waned, and the python became a beloved resident of the science building among parrots, finches, turtles, lizards and exotic birds over the years,” said Jenny. “Bob and John named her Kali, after the Hindu goddess of destruction, and there were many jokes about how slacking Plan students might end up in the python area.”

Despite the jokes, Kali was a gentle soul who had many admirers and regular visitors: young kids from the community, surprised prospective students and of course devoted science students and faculty members. “Other translations of her Hindu name are more fitting: Kali, the ‘goddess of time and change’ and ‘goddess of eternal energy,’” said Jenny. “We will miss Kali.”

And more

A group show at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, featuring new work by Marlboro art faculty Marina Lantin (ceramics), John Willis (photography), Cathy Osman (painting) and Tim Segar (sculpture), opened in November. Titled Four Eyes: Art from Potash Hill, the show will continue through February 5. Photo by Joanna Moyer-Battick

Last June, a few of Marlboro’s former Oxford classics fellows, math fellows and alumni gathered with Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president, Ted Wendell, trustee, and Mary Wendell for a reunion at the British Academy in London. Those attending included (from left to right) Ted Wendell, Nicolas Barber, Geoffrey Fallows, Robin Jackson, David Middleton, former math fellow Charlotte Watts, ecologist Chris Carbone ’88, Robert Wendt, artist Pat Kauffman ’74, Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, Mark Pobjoy, Philip DeMay, Emma Park, former math fellow John Arhin and current classics fellow William Guast. Photo by Claudine Hartzel

John MacDonald of Shaftsbury, Vermont, who was born in Hendricks House in 1927, stopped by the campus for a visit in October. His family owned 1,300 acres here and farmed and logged the land. After his father died, his mother, pregnant with twins, sold the farm to Marlboro founder Walter Hendricks and moved to the Northeast Kingdom. Photo by Dianna Noyes

John MacDonald of Shaftsbury, Vermont, who was born in Hendricks House in 1927, stopped by the campus for a visit in October. His family owned 1,300 acres here and farmed and logged the land. After his father died, his mother, pregnant with twins, sold the farm to Marlboro founder Walter Hendricks and moved to the Northeast Kingdom. Photo by Dianna Noyes

Worthy of note

For those of us who dreaded making mistakes in math, the words of mathematics fellow Jean-Martin Albert (right) are a balm to the soul. “I want the students to fall into traps,” he said cheerfully, “to make mistakes and learn to see exactly where they made them and how to recover from them.” Jean-Martin’s enthusiasm for math shows that it can actually be fun, even useful. He received his M.Sc. in mathematics from the University of Calgary and is currently completing his doctorate in mathematics at McMaster University. Jean-Martin’s research interests are in mathematical logic, specifically something new and mysterious called continuous model theory and its applications to functional analysis.

For those of us who dreaded making mistakes in math, the words of mathematics fellow Jean-Martin Albert (right) are a balm to the soul. “I want the students to fall into traps,” he said cheerfully, “to make mistakes and learn to see exactly where they made them and how to recover from them.” Jean-Martin’s enthusiasm for math shows that it can actually be fun, even useful. He received his M.Sc. in mathematics from the University of Calgary and is currently completing his doctorate in mathematics at McMaster University. Jean-Martin’s research interests are in mathematical logic, specifically something new and mysterious called continuous model theory and its applications to functional analysis.

“I feel fortunate to be working at a place where I can just go and do some hands-on art sometimes,” said ceramics professor Martina Lantin. Last July, she and fellow art faculty member Cathy Osman attended a two-week silk-screening workshop at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, in Maine. Martina was working on patterned, silkscreened wallpaper, to be used as part of her installation at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center. “Having done plate installations on walls for many years, there is always the question of what lives behind the plates, and what is the relationship between the plates and wall. With the wallpaper, I see a conversation happening between the two.”

“Critical thinking is the bedrock of a functioning democracy and successful attempts to transform the world,” said social science fellow Renée Byrd (right), who is excited by Marlboro’s unique, student-driven approach to education. Renée received her bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies from Mills College, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in feminist studies at the University of Washington. Her research focuses on contemporary prisons, neoliberal political rationalities and the politics of race, gender and sexuality. She has worked as a legal advocate for women prisoners in California and as a family advocate for youth involved in the juvenile justice system.

“Critical thinking is the bedrock of a functioning democracy and successful attempts to transform the world,” said social science fellow Renée Byrd (right), who is excited by Marlboro’s unique, student-driven approach to education. Renée received her bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies from Mills College, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in feminist studies at the University of Washington. Her research focuses on contemporary prisons, neoliberal political rationalities and the politics of race, gender and sexuality. She has worked as a legal advocate for women prisoners in California and as a family advocate for youth involved in the juvenile justice system.

Once again, Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson confirmed for us that Spanish language, culture and literature have much to offer. In October, Rosario received the Victoria Urbano Award in drama, presented by the Asociación Internacional de Literatura y Cultura Femenina Hispánica (AILCFH) for her play titled Metamorphosis before the Obsidian Mirror: Monologue in Two Acts. She also presented a paper in September at an international conference at Howard University called “Africa and People of African Descent: Issues and Actions to Re-Envision the Future.” Her paper, “Dance as female affirmation in Ekomo, a novel from Equatorial Guinea,” was based on her recent research on Guinean literature (Potash Hill, Summer 2011, page 8).