Spring 2020

Editor’s Note

“Scientific careers, like life itself, are usually a work in progress,” says Charles Curtin ’86 in his feature on new perspectives on landscape-scale ecology and conservation in this issue of Potash Hill. “Like a series of experiments, one’s thinking evolves to reflect emerging realities.” There’s been a whole lot of emerging realities at this venerable institution of higher learning known, for now, as Marlboro College, and much of this issue contends with the college’s work in progress.

“Scientific careers, like life itself, are usually a work in progress,” says Charles Curtin ’86 in his feature on new perspectives on landscape-scale ecology and conservation in this issue of Potash Hill. “Like a series of experiments, one’s thinking evolves to reflect emerging realities.” There’s been a whole lot of emerging realities at this venerable institution of higher learning known, for now, as Marlboro College, and much of this issue contends with the college’s work in progress.

One would be excused for being suspicious. In the last issue of Potash Hill (Fall 2019), yours truly was singing the praises of a planned merger with University of Bridgeport, which had fallen through before the magazine even mailed. This time feels different. The proposed Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies has been made possible by our alliance with a trusted and well-known partner, Emerson College. Although it means the loss of Potash Hill, a place central to Marlboro’s history and appeal, it also means the preservation of much that the college holds dear.

This issue of Potash Hill will give you a glimpse of how working groups are charting the best path forward for faculty, students, staff, and the campus itself, and how students are working to document the last semester on campus. It shares the many visits between members of the Marlboro and Emerson communities, and promotes the important work of the recently relaunched Alumni Association. And, of course, much more.

What will happen to Potash Hill, the magazine? It is our sincere hope to publish one more print issue in the fall, in which we can celebrate the last graduating class and generally ponder Marlboro’s legacy going forward. That is why this issue is being published online, primarily, to conserve resources and prepare for that final issue. What will happen after that, well, let’s just say it’s a work in progress!

How is your thinking evolving? What is Marlboro’s legacy? What kind of an impact did the college have on your life? As always, we love to hear from our readers at pjohansson@marlboro.edu.

—Philip Johansson, editor

Inside Front Cover

Potash Hill

Published twice every year, Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community members, in both undergraduate and graduate programs, are doing, creating, and thinking. The publication is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium carbonate, was a locally important industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates.

Editor: Philip Johansson

Alumni Director: Maia Segura ’91

Staff Photographers: Emily Weatherill ’21 and Clement Goodman ’22

Staff Writer: Sativa Leonard ’23

Design: Falyn Arakelian

Potash Hill welcomes letters to the editor. Mail them to: Editor, Potash Hill, Marlboro College, P.O. Box A, Marlboro, VT 05344, or send email to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. The editor reserves the right to edit for length letters that appear in Potash Hill.

Front Cover: The Serkin Center for the Performing Arts takes on an air of ambiguity as reflected in the campus fire pond. The future of the campus has been on the mind of many, as Marlboro College prepares to enter an alliance with Emerson College. Photo by Richard Smith

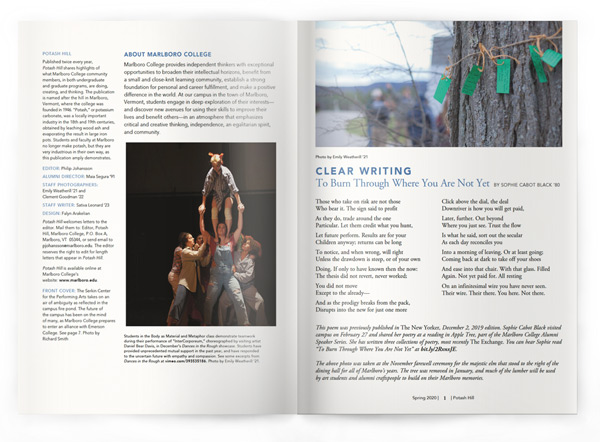

Students in the Body as Material and Metaphor class (right) demonstrate teamwork during their performance of “InterCorporeum,” choreographed by visiting artist Daniel Bear Davis, in December’s Dances in the Rough showcase. Students have provided unprecedented mutual support in the past year, and have responded to the uncertain future with empathy and compassion. See some excerpts from Dances in the Rough. Photo by Emily Weatherill ‘21.

Students in the Body as Material and Metaphor class (right) demonstrate teamwork during their performance of “InterCorporeum,” choreographed by visiting artist Daniel Bear Davis, in December’s Dances in the Rough showcase. Students have provided unprecedented mutual support in the past year, and have responded to the uncertain future with empathy and compassion. See some excerpts from Dances in the Rough. Photo by Emily Weatherill ‘21.

About Marlboro College

Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests while developing transferrable skills that can be directly correlated with success after graduation, known as the Marlboro Promise. These skills are: (1) the ability to write with clarity and precision; (2) the ability to work, live, and communicate with a wide range of individuals; and (3) the ability to lead an ambitious project from idea to execution. Marlboro students fulfill this promise in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, and community.

Up Front

Keeping it Experiential

“During the semester when readings and papers pile up, it’s easy to take for granted the ‘mundane’ things—a hot cup of coffee, clean dishes, good winter boots, easily moving five miles down the road—but these seemingly little things keep us alive, get us moving, and give our brains the needed time to process and rest.

“The hands-on, experiential learning of expedition trips is an essential counterpart to classroom work. I’ve had more epiphanies driving a stretch of highway in South Dakota than I ever did in the process of writing a paper for class. When these trips are in their element, whether the Rocky Mountains or the Green Mountains, they provide the perfect environment for the ‘aha’ moments and fuel for better learning.”

— Nikolas Katrick ’07, MSM ’16, Outdoor Program Director

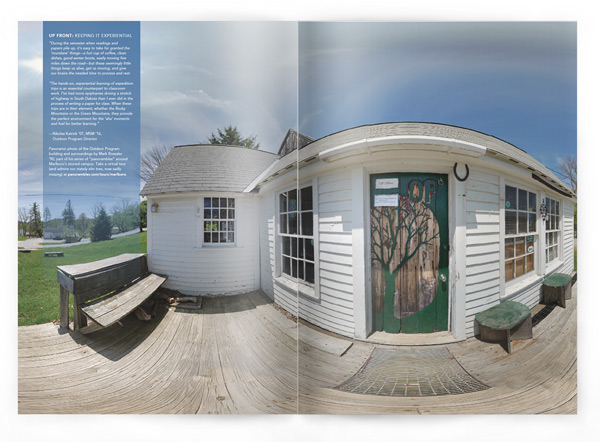

Panoramic photo of the Outdoor Program building and surroundings by Mark Roessler ’90, part of his series of “panorambles” around Marlboro’s storied campus. Take a virtual tour (and admire our stately elm tree, now sadly missing) at panorambles.com/tours/marlboro.

Clear Writing

To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet

By Sophie Cabot Black '80

Those who take on risk are not those

Who bear it. The sign said to profit

As they do, trade around the one

Particular. Let them credit what you hunt,

Let future perform. Results are for your

Children anyway; returns can be long

To notice, and when wrong, will right

Unless the drawdown is steep, or of your own

Doing. If only to have known then the now:

The thesis did not revert, never worked;

You did not move

Except to the already—

And as the prodigy breaks from the pack,

Disrupts into the new for just one more

Click above the dial, the deal

Downriver is how you will get paid,

Later, further. Out beyond

Where you just see. Trust the flow

Is what he said, sort out the secular

As each day reconciles you

Into a morning of leaving. Or at least going;

Coming back at dark to take off your shoes

And ease into that chair. With that glass. Filled

Again. Not yet paid for. All resting

On an infinitesimal wire you have never seen.

Their wire. Their there. You here. Not there.

This poem was previously published in The New Yorker, December 2, 2019 edition. Sophie Cabot Black visited campus on February 27 and shared her poetry at a reading in Apple Tree, part of the Marlboro College Alumni Speaker Series. She has written three collections of poetry, most recently The Exchange. You can hear Sophie read “To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet.”

The above photo was taken at the November farewell ceremony for the majestic elm that stood to the right of the dining hall for all of Marlboro’s years. The tree was removed in January, and much of the lumber will be used by art students and alumni craftspeople to build on their Marlboro memories.

Letters

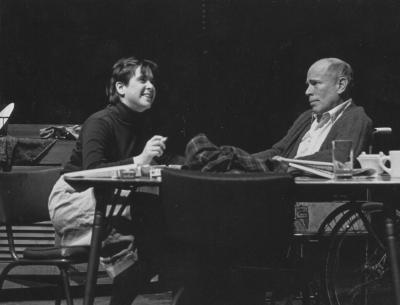

Remembering Hillary  I sent a poem I wrote the day I found out Hilary Sloin had died (Potash Hill Fall 2019), but asked that it not be considered for Potash Hill because I expressed anger at her for dying, and because I used cuss words. And then I thought of the years she and I worked with T. Wilson in Poetry Workshop. Hil and I were so serious about writing then and, gratifyingly, T. took us seriously. It was the best writing training I’ve ever had—sitting in that sunny classroom, high up in an old barn, arguing about whether one word or another was extraneous.

I sent a poem I wrote the day I found out Hilary Sloin had died (Potash Hill Fall 2019), but asked that it not be considered for Potash Hill because I expressed anger at her for dying, and because I used cuss words. And then I thought of the years she and I worked with T. Wilson in Poetry Workshop. Hil and I were so serious about writing then and, gratifyingly, T. took us seriously. It was the best writing training I’ve ever had—sitting in that sunny classroom, high up in an old barn, arguing about whether one word or another was extraneous.

I think the poem would pass a workshop criticism. I think Hil would be ok with the F-bombs and the anger. We were estranged for years, but she was never far from my thoughts and a couple years ago I found her again. We were both working on old furniture and selling old stuff. Both single, living with our dogs and driving old pickup trucks. Our apples didn’t fall far.

In fact, we first met in the apple trees next to the dining hall. We climbed the apple trees and talked like third graders: what do you like, what’s cool. We never agreed on everything but we related to each other a lot. She was funny, she was sweet, she was opinionated, she wasn’t always right, she made me laugh. She was an amazingly hard-working and talented writer. I’m lucky I knew her.

—Rachel Mendez ’85

Sacred Singing

I’m a PhD student at the University of Illinois and am working on my dissertation about Sacred Harp singing in the northeast. I found a reference to an article in Potash Hill, Spring of 1981, by Anthony Barrand and Carole Moody, called “The Making of Northern Harmony.” I was wondering if it’s possible to acquire this article either through your office, the library, or elsewhere on campus. Thanks very much for any help you can offer.

—Jonathon Smith

Marlboro’s archivist fellow Megan O’Loughlin was able to locate this issue of Potash Hill in the library and sent a scan of “The Making of Northern Harmony” to Jonathon, which you can find here: marlboro.edu/harmony. —ed.

Last Potash Hill?

If things go well with Emerson College as planned, this Potash Hill stands to be the penultimate issue, with one more published in Fall 2020 to honor our last graduating class on campus, make some cumulative sense of Marlboro’s legacy, and prepare readers for what might come next. Readers are encouraged to contribute to this final issue, in the form of letters, memories, vignettes, poems, or pictures. What was your favorite class? Who was your biggest crush? What was your ultimate Marlboro experience? What did this land that we all hold dear mean to you? Please send your memories to pjohansson@marlboro.edu. We will publish as many submissions as space allows, and post the remainder online.

Errata

As an alumna who graduated last May, I was able to see firsthand some of the work that was done with CASP and the asylum seekers (Potash Hill Fall 2019). I noticed that one of the main participants in the committee, Rosario de Swanson, a professor who has gone above and beyond in her work for the college, was not mentioned in the article. I hope there will be some acknowledgement of this error and that it will be made right.

—Alicia Lowden ’19

Thanks, Alicia, for keeping us honest. Rosario’s name was added to the digital version of the Fall 2019 Potash Hill. Please accept our apologies. —ed.

Potash Hill regrets that we misspelled the name of departed staff member Karleen Crossman in her obituary. —ed.

View from the Hill

Embracing Uncertainty

By Kevin F. F. Quigley

Last December’s Dances in the Rough was an amazing showcase of student work, demonstrating a depth of curiosity and passion for learning that characterizes Marlboro College. One of the most inspiring performances was called “A Two-Part Experiment in Not Knowing,” choreographed by Alta Millar ’20 and performed by Alta and Charlie Hickman ’21.

Punctuating the dance with seemingly random movements and drawing members of the audience into their tangled web of uncertainty, Alta and Charlie posed questions that required “the practice of being comfortably unsure.” Their insights were particularly poignant during this uncertain time as we work to forge Marlboro’s alliance with Emerson College.

There are so many reasons to be anxious during this momentous transition, and my heart goes out to everyone on whom this uncertainty has taken a toll. Since the announcement of the Emerson alliance in November, both communities have made great strides in learning about each other’s strengths, finding synergies, and charting a new path together. Some of this work you can read about in this issue of Potash Hill, but much of it is necessarily still a work in progress.

In the meantime, of course, students have questions about what classes they can take, or if the faculty they planned on working with will be moving to Emerson. Faculty have questions about what their curriculum will look like, or what physical spaces will be available to them. Alumni and Marlboro townspeople have questions about the future of the campus and Marlboro’s legacy. There will be answers to all of these, but not until Marlboro and Emerson sign a more binding agreement. While I am optimistic that an agreement will be reached soon, it is still pending at the time of this publication.

The devil is in the details, as always. Many people who are passionate about the success of the Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies are working hard on sorting out these details, and I am heartened and inspired by their continued progress. I am also grateful to the board of trustees for addressing our insurmountable financial and enrollment challenges now, while Marlboro still has the resources to forge a partnership that ensures the continuation of our mission and identity, while also providing remarkable opportunities for our faculty and students who choose to go to the Marlboro Institute at Emerson.

In the current landscape of many small New England colleges closing abruptly in the face of similar challenges, we consider ourselves lucky. But we have traded certain abruptness for uncertainty, as we have taken this period of time to make the Emerson alliance the best it can possibly be, for all parties involved. We have chosen the path of being “comfortably unsure” because of the promise that path holds.

You can find the latest details of Marlboro’s alliance with Emerson at marlboro.edu/partnership.

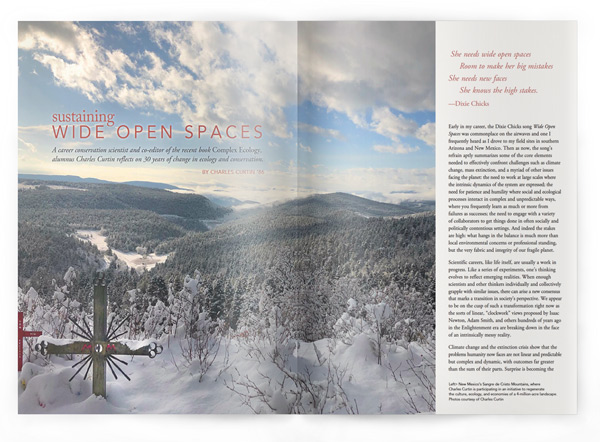

Sustaining Wide Open Spaces

By Charles Curtin '86

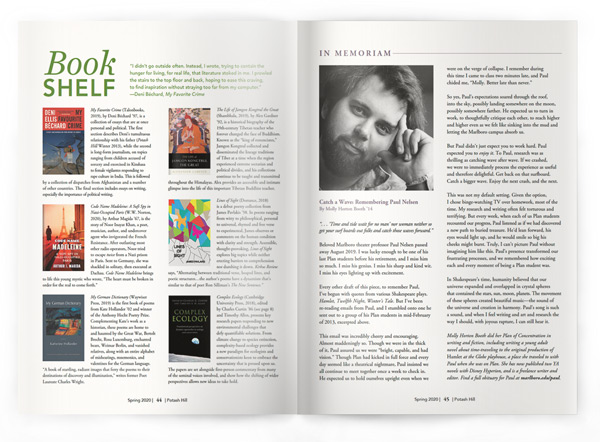

A career conservation scientist and co-editor of the recent book Complex Ecology, alumnus Charles Curtin reflects on 30 years of change in ecology and conservation.

She needs wide open spaces Room to make her big mistakes She needs new faces She knows the high stakes. —Dixie Chicks

Early in my career, the Dixie Chicks song Wide Open Spaces was commonplace on the airwaves and one I frequently heard as I drove to my field sites in southern Arizona and New Mexico. Then as now, the song’s refrain aptly summarizes some of the core elements needed to effectively confront challenges such as climate change, mass extinction, and a myriad of other issues facing the planet: the need to work at large scales where the intrinsic dynamics of the system are expressed; the need for patience and humility where social and ecological processes interact in complex and unpredictable ways, where you frequently learn as much or more from failures as successes; the need to engage with a variety of collaborators to get things done in often socially and politically contentious settings. And indeed the stakes are high: what hangs in the balance is much more than local environmental concerns or professional standing, but the very fabric and integrity of our fragile planet.

Scientific careers, like life itself, are usually a work in progress. Like a series of experiments, one’s thinking evolves to reflect emerging realities. When enough scientists and other thinkers individually and collectively grapple with similar issues, there can arise a new consensus that marks a transition in society’s perspective. We appear to be on the cusp of such a transformation right now as the sorts of linear, “clockwork” views proposed by Isaac Newton, Adam Smith, and others hundreds of years ago in the Enlightenment era are breaking down in the face of an intrinsically messy reality.

Climate change and the extinction crisis show that the problems humanity now faces are not linear and predictable but complex and dynamic, with outcomes far greater than the sum of their parts. Surprise is becoming thenew norm. Events such as Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake and tsunami at Fukushima highlight the need for a different kind of science and policy, one that addresses challenges with a new humility and pragmatism. My own journey of discovery parallels this important transition in scientific thinking.

Climate change and the extinction crisis show that the problems humanity now faces are not linear and predictable but complex and dynamic, with outcomes far greater than the sum of their parts. Surprise is becoming thenew norm. Events such as Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake and tsunami at Fukushima highlight the need for a different kind of science and policy, one that addresses challenges with a new humility and pragmatism. My own journey of discovery parallels this important transition in scientific thinking.

The first phase of my evolving thinking on science and complexity began with my time at Marlboro College, where my professors (especially Bob Engel) introduced me to the view that quality science was both rigorous and elegant. Classic ecological studies, such as those of luminary ecologist and Marlboro alumnus Robert MacArthur (brother of Marlboro physics professor John), transformed ecology from primarily a descriptive to a quantitative discipline. But equally important, the MacArthur brothers and collaborators showed experimental ecology to be something of immense beauty.

In paraphrasing Pablo Picasso, Robert once stated, “Science is the lie that helps us see the truth,” recognizing that science, like art, is as much about insight as a search for objective reality. Especially in the post-war era from the 1950s through the early 1980s, the relatively simple math available to ecologists before computational power became widespread meant that much of the science of the period was a gross simplification of reality. But this simplification led to an elegance and focus on big conceptual questions that have rarely been attempted since.

Following Marlboro, my graduate career was also marked by a search for conceptual elegance. From research on the recovery of subalpine ecosystems in Colorado to studies on the impact of climate and land-use change on species, my approach embraced a search for simple solutions to complex challenges. This was followed by a post-doc at the University of New Mexico with ecologist James H. Brown, managing studies of desert ecological communities (work I had read and admired as an undergraduate at Marlboro).

Brown’s work was another series of exceedingly elegant experiments that provided clarity through simplifications of reality. However, during my post-doc, I also had the opportunity to spend time at a complex-system think tank, the Santa Fe Institute (SFI). My time at SFI would forever change the way I viewed science and conservation, by recognizing that elegance did not necessarily require a focus on simplification. Instead, a fundamental challenge of science and conservation was to embrace reality by grappling with complexity.

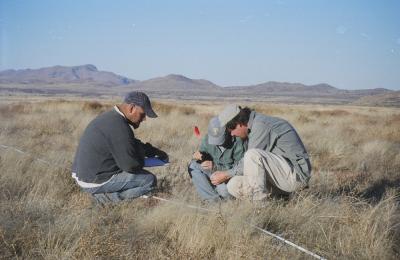

Out of my interest in demonstrating that experimental ecology could incorporate complexity arose the McKinney Flats Project, a nearly 9,000-acre experiment in southern New Mexico. This project was a microcosm of study plots spanning a million-acre conservation planning area, and was intended to provide insight into the dynamics playing out across the entire intermountain West. However, it soon became apparent that to understand systems at the size of even 9,000 acres would take at least 12 to 16 years. This period was far too long to acquire the requisite publications to attain tenure at most universities. So a new sort of science was needed, one embedded in vast landscapes and that involved working closely with remote rural communities.

I left academia and founded a nonprofit research institute that provided the institutional flexibility and ability to produce the answers I thought society most needed. As it turned out, McKinney Flats was as much a social experiment as a biological one. I was simultaneously having cowboys manage a 200-head herd of cattle, undertaking 8,000-acre prescribed burns, introducing species such as prairie dogs, and working with biologists on a diversity of ecological sampling. Doing all this while also sustaining a partnership with the rancher-led conservation organization Malpai Borderlands Group proved to be both challenging and insightful. No longer was I applying comparatively simple, replicated experimental designs, but working amid the intrinsic messiness of the “real world,” where social dynamics are just as important as ecological ones.

I left academia and founded a nonprofit research institute that provided the institutional flexibility and ability to produce the answers I thought society most needed. As it turned out, McKinney Flats was as much a social experiment as a biological one. I was simultaneously having cowboys manage a 200-head herd of cattle, undertaking 8,000-acre prescribed burns, introducing species such as prairie dogs, and working with biologists on a diversity of ecological sampling. Doing all this while also sustaining a partnership with the rancher-led conservation organization Malpai Borderlands Group proved to be both challenging and insightful. No longer was I applying comparatively simple, replicated experimental designs, but working amid the intrinsic messiness of the “real world,” where social dynamics are just as important as ecological ones.

Although the McKinney Flats study ended prematurely, due to the 2007–2008 recession and concurrent social upheaval along the US-Mexico border, valuable lessons had been learned. I found that effective science and conservation are a result of social design as much as scientific replication—putting in place the preconditions for success that most biological scientists and conservationists rarely consider. I recognized that there needed to be a greater synthesis of social and ecological approaches.

My experience gave me a new perspective now widely accepted, but still seldom attained, where one does not think along purely disciplinary boundaries but views disciplines as different tools in a diverse tool kit. The role of the researcher is to select the right tool for the job, rather than merely applying a paradigm because it is what you know. Theories were no longer suppositions to be defended, but ideas to be explored and thoughtfully challenged. Complexity is embraced, rather than avoided— the intrinsic messiness of the world is designed into the study, rather than designed out of it.

In tandem with McKinney Flats, and in the years that followed, I embarked on a wide range of social and ecological experiments related to collaborative science and conservation. This work engaged a wide array of stakeholders in large-scale problem solving with a focus on involving local people and their values and insights in science and policy. These efforts included fishery recovery in the western Atlantic, collaborative conservation programs in East Africa and the Middle East, and farmer cooperatives in the Midwest and New England. I also co-founded programs on collaboration, complexity, and adaptive management at MIT and other universities.

These experiences were followed by a return to on-the-ground efforts in collaborative conservation in Montana, where what I learned was sobering. It soon became apparent the ideas gleaned from my earlier efforts in large-scale science and conservation were necessary, but not sufficient to keep pace with the increasing rates of environmental and societal change. To mix metaphors, the best of conventional conservation was still mainly a process of rearranging deck chairs (while Rome burns). Yes, we were restoring watersheds and saving a few wolves or grizzly bears. However, we were not fundamentally addressing the most severe threats such as global environmental change, or wholesale transformations of local or indigenous cultures. This was because we were not meaningfully addressing the limitations undermining most science and policy. A fundamental rethink of conservation was needed.

These experiences were followed by a return to on-the-ground efforts in collaborative conservation in Montana, where what I learned was sobering. It soon became apparent the ideas gleaned from my earlier efforts in large-scale science and conservation were necessary, but not sufficient to keep pace with the increasing rates of environmental and societal change. To mix metaphors, the best of conventional conservation was still mainly a process of rearranging deck chairs (while Rome burns). Yes, we were restoring watersheds and saving a few wolves or grizzly bears. However, we were not fundamentally addressing the most severe threats such as global environmental change, or wholesale transformations of local or indigenous cultures. This was because we were not meaningfully addressing the limitations undermining most science and policy. A fundamental rethink of conservation was needed.

As the social philosopher Tom Atlee noted, “Things are getting better and better and worse and worse, faster and faster, simultaneously,” and current institutions are typically poorly situated to address this reality. Conservation actions too frequently represent halfway measures—in essence, the settling for less damaging outcomes, rather than fundamentally better solutions. In my career, I have to admit, I have too often been complacent in accepting such “solutions.” There were marine policies that mayhave reduced the decline of fisheries but didn’t address the core issue of unsustainable fishing practices, and collaborative organizations that protected endangered species but didn’t address agricultural practices that degrade watersheds and increase greenhouse gases.

Conventional collaborative approaches were essential in building common ground and an understanding of how to conduct conservation at large scales. It is certainly not appropriate to cast aside such testbeds of innovation and problem solving, for they have made enormous contributions to preserving communities and species. However, we need to learn and apply the lessons from decades of experience that have much to teach us about how to design, develop, and sustain more integrated efforts that consider the whole system and not just fragments. In short, we need to move beyond reactive to proactive approaches and policies.

The disappointments of Rio, Paris, and other climate accords, and the relative impermanence of global and national climate policy, strongly suggest that if effective action is to happen, it is not going to come from global agreements but from local engagement and action. It has to be built from the ground up, and right now we’re trying such an approach in the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

The Sangre de Cristo Initiative is seeking to regenerate the culture, ecology, and economies of a 4-million-acre landscape from north-central New Mexico to south-central Colorado. The point of this initiative is to show that conservation is not only sustainable, but can contribute to the integrity of social and ecological systems. Especially in some of the poorest counties in the US, we need to do more than protect nature. We need integrated solutions to the coupled challenges of rising global temperatures and the conservation of species and ecosystems, while engaging disenfranchised rural populations. We’re exploring using biomass energy production technologies to restore forest and watershed health, and fuel economic revitalization of the region while reducing CO2 inputs into the atmosphere.

There are many ways we can rethink conservation and science, but we must recognize that the status quo is often not sufficient, or perhaps even ethical, given the extent of current threats. Projects such as the Sangre de Cristo Initiative illustrate there are alternative frameworks that can make conservation and environmental science more effective in their service to society and the planet. These approaches bring together decades of experience searching for elegance and integrity, incorporating multiple viewpoints, and working across disciplines and ecological boundaries. They require humility to work with what Buddhist teachings call shoshin, or a “beginner’s mind,” where you address complex challenges with eagerness, openness, and a lack of preconceptions. Lastly, these new approaches to conservation include viewing actions as experiments, so one can truly learn from them.

“For a scientist there are worse sins than being wrong; one of them is being trivial.” —Robert H. MacArthur

Charles Curtin is a landscape ecologist and systems design theorist and practitioner who works at the intersection of science and policy, and is founder of BioCultural Connections in New Mexico. He is the author of The Science of Open Spaces: Theory and Practice for Conserving Large, Complex Systems and co-editor of Complex Ecology: Foundational Perspectives on Dynamic Approaches to Ecology and Conservation. His forthcoming book with the working title Prosilience: The Science of Complexity and Integrity is due out next year.

Ecology of the Individual  “Plants are often regarded as no more than resource objects— unfeeling, passive sorts of beings,” says Hailey Mount ’19, who completed her Plan in ecology and environmental philosophy in December. “But new science, technology, and attention to sustainable environmental relationships are allowing us to view the plant world with a new level of detail.” Hailey used a trait-based method of ecology—specifically, looking at the level of individual variation and scaling up and down between other levels from there—to look at how soil acidification could affect tree dynamics in Marlboro’s ecological reserve (Spring 2018 Potash Hill). “I’m exploring how these new techniques in ecology, and the philosophical idea of plants as subjective ‘others’ worthy of empathetic consideration, can come together and improve our environmental relationships, our management practices, and the way we interact with the world.”

“Plants are often regarded as no more than resource objects— unfeeling, passive sorts of beings,” says Hailey Mount ’19, who completed her Plan in ecology and environmental philosophy in December. “But new science, technology, and attention to sustainable environmental relationships are allowing us to view the plant world with a new level of detail.” Hailey used a trait-based method of ecology—specifically, looking at the level of individual variation and scaling up and down between other levels from there—to look at how soil acidification could affect tree dynamics in Marlboro’s ecological reserve (Spring 2018 Potash Hill). “I’m exploring how these new techniques in ecology, and the philosophical idea of plants as subjective ‘others’ worthy of empathetic consideration, can come together and improve our environmental relationships, our management practices, and the way we interact with the world.”

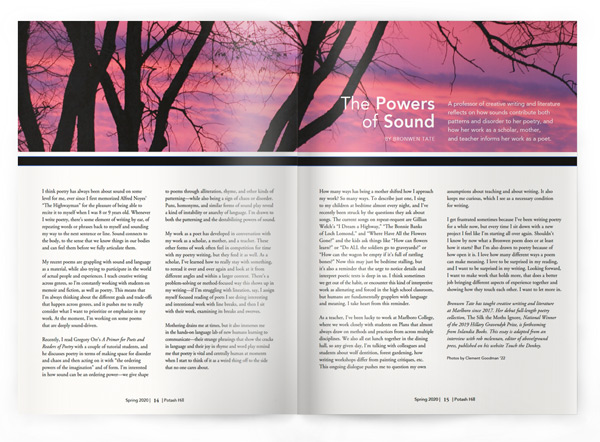

The Powers of Sound

By Bronwen Tate

A professor of creative writing and literature reflects on how sounds contribute both patterns and disorder to her poetry, and how her work as a scholar, mother, and teacher informs her work as a poet.

I think poetry has always been about sound on some level for me, ever since I first memorized Alfred Noyes’ “The Highwayman” for the pleasure of being able to recite it to myself when I was 8 or 9 years old. Whenever I write poetry, there’s some element of writing by ear, of repeating words or phrases back to myself and sounding my way to the next sentence or line. Sound connects to the body, to the sense that we know things in our bodies and can feel them before we fully articulate them.

My recent poems are grappling with sound and language as a material, while also trying to participate in the world of actual people and experiences. I teach creative writing across genres, so I’m constantly working with students on memoir and fiction, as well as poetry. This means that I’m always thinking about the different goals and trade-offs that happen across genres, and it pushes me to really consider what I want to prioritize or emphasize in my work. At the moment, I’m working on some poems that are deeply sound-driven.

Recently, I read Gregory Orr’s A Primer for Poets and Readers of Poetry with a couple of tutorial students, and he discusses poetry in terms of making space for disorder and chaos and then acting on it with “the ordering powers of the imagination” and of form. I’m interested in how sound can be an ordering power—we give shape to poems through alliteration, rhyme, and other kinds of patterning—while also being a sign of chaos or disorder. Puns, homonyms, and similar forms of sound play reveal a kind of instability or anarchy of language. I’m drawn to both the patterning and the destabilizing powers of sound.

My work as a poet has developed in conversation with my work as a scholar, a mother, and a teacher. These other forms of work often feel in competition for time with my poetry writing, but they feed it as well. As a scholar, I’ve learned how to really stay with something, to reread it over and over again and look at it from different angles and within a larger context. There’s a problem-solving or method-focused way this shows up in my writing—if I’m struggling with lineation, say, I assign myself focused reading of poets I see doing interesting and intentional work with line breaks, and then I sit with their work, examining its breaks and swerves.

Mothering drains me at times, but it also immerses me in the hands-on language lab of new humans learning to communicate—their strange phrasings that show the cracks in language and their joy in rhyme and word play remind me that poetry is vital and centrally human at moments when I start to think of it as a weird thing off to the side that no one cares about.

How many ways has being a mother shifted how I approach my work? So many ways. To describe just one, I sing to my children at bedtime almost every night, and I’ve recently been struck by the questions they ask about songs. The current songs on repeat-request are Gillian Welch’s “I Dream a Highway,” “The Bonnie Banks of Loch Lomond,” and “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and the kids ask things like “How can flowers learn?” or “Do ALL the soldiers go to graveyards?” or “How can the wagon be empty if it’s full of rattling bones?” Now this may just be bedtime stalling, but it’s also a reminder that the urge to notice details and interpret poetic texts is deep in us. I think sometimes we get out of the habit, or encounter this kind of interpretive work as alienating and forced in the high school classroom, but humans are fundamentally grapplers with language and meaning. I take heart from this reminder.

As a teacher, I’ve been lucky to work at Marlboro College, where we work closely with students on Plans that almost always draw on methods and practices from across multiple disciplines. We also all eat lunch together in the dining hall, so any given day, I’m talking with colleagues and students about wolf dentition, forest gardening, how writing workshops differ from painting critiques, etc. This ongoing dialogue pushes me to question my own assumptions about teaching and about writing. It also keeps me curious, which I see as a necessary condition for writing.

I get frustrated sometimes because I’ve been writing poetry for a while now, but every time I sit down with a new project I feel like I’m starting all over again. Shouldn’t I know by now what a Bronwen poem does or at least how it starts? But I’m also drawn to poetry because of how open it is. I love how many different ways a poem can make meaning. I love to be surprised in my reading, and I want to be surprised in my writing. Looking forward, I want to make work that holds more, that does a better job bringing different aspects of experience together and showing how they touch each other. I want to let more in.

Bronwen Tate has taught creative writing and literature at Marlboro since 2017. Her debut full-length poetry collection, The Silk the Moths Ignore, National Winner of the 2019 Hillary Gravendyk Prize, is forthcoming from Inlandia Books. This essay is adapted from an interview with rob mclennan, editor of above/ground press, published on his website Touch the Donkey. Photos by Clement Goodman ’22

Poetry by Bronwen Tate

Reproductions of Frescoes

Travel back. Because of a misstep, I saw a crevice in a horse’s

Travel back. Because of a misstep, I saw a crevice in a horse’s

knee in place of brigands. Play of light and color off their helms.

Reading in the original French. Reading to be elsewhere. I look

past it, first conception.

I read Proust. In wide-sleeved houppelande, she incarnates.

Swollen fruit of her manly form a solid allusion. Prod that

membrane edged with ribbons of watercress or cuckoo flower.

For each word, a word in another language means part of the

same thing. When I look up “midwife” on the university website,

the only reference is to Plato. Theaetetus, he suggests, is in discomfort

because he is in intellectual labour.

I want to be a scholar. I want a new vernacular of milk.

Echo, echo, on my perch with my library. Well-stocked dictionary

sends me Latin, lygeum spartum, cultivated or not present here.

I Could Not Ask Other Flowers

Today multiplied.

A layered wealth of strata along the sloped face of the work. Ankle

bone, wind-blown grain, suck of honeysuckle, cell of honeycomb.

Approach the hedgerow with reverence due a rood loft (consent,

oh Lord, to bless). Spade in hand, cleave what knotted. I am

of the same stripe as she who cries into the thorned canopy. I

follow her gaze to the engraved steeple, bricked with birds’ nests.

Talus, alveolus, speak the landscape of a body. Thoughts pile

up, bent, twined, twisted as flowers.

Circumstances Legible Behind This Window

What is raw in me again, burst blister, lamb’s lettuce.

Fixed to hang on syllables, frivolous and drowsing. All modifiers

are contagious. Complacent. Glowing. All modifiers slip me in

the direction of the sea.

Without the residue of fixed habits, I loosen my gauge to make

sweet the absences. Lace is made of holes. Like a bassinet on a

lower step, my hum rocks side to side. Water diminishes in the

basin as the days grow drier. I say guard and mean keep.

To Hold What's Tender

Baby bathes

My lip bruised

from his hard crown

Lean down

his palm along my cheek

repeating “gentle”

hurts a little

Bruised Peaches

We measure days in peaches, bruises, livid, lose the keys

Find them days later in the dirty laundry. What is habit

That it wakes me up to effort? I cook but don’t dust, read

In bed, wash the sheets occasionally. Eat the peaches

Before they mold, wear wool socks against a cold July.

My signature slants “O” to a recognizable angle—what is

Unnoticed is unchanging; the B negative of my blood, unchecked,

Will reject babies that could have poisoned me in another age.

Might effort tilt the ratios of my articles, definite stamp of

All I’ve heard and hardened indefinite in what I make. A child is

Variable flung from the cells, being, substance-sewn

Self. In coming hours, a turn, determined angle, harkening,

Effortless. Biology wakes me to that cry. Subterranean

Singing through the fabric, thin-spread-thing, I am still here.

Umbilical

Blue umbilical pulse to cut, my last placenta

Stuck, the doctor scrubbed elbow-deep, that flesh

Suddenly neither of us, excess, would rot inside me.

I held him, purple still and scrawny, bawling.

Hot blankets, shivering, sweat-wracked, hormone high—

What is in the body, yours, mind, all mouth? We are

Our parts, not a self apart, grow new ancillaries, collaborate

On blood. My son nears three now, swipes and taps

Glass-faced watch-hands, asks if the umbilicus plugs

Into the wall, charged up on Coca-Cola, wails, “hard peaches

Are my favorite.” He wants what’s unripe. I slice and macerate

With sweet and salt and mint, tired now beyond cheek’s fuzz

And bloom. New one, I made you a room inside my mind.

Still you’ll split my skin to quit me.

“Reproduction of Frescos,” “I Could Not Ask Other Flowers,” and “Circumstances Legible Behind This Window,” were previously published in Touch the Donkey, #21.

The Inadequacy of Words

“Memory, like a good poem, can be returned to again and again, yielding new meanings from new angles,” says Brooke Evans ’19, who completed their Plan in writing in December. “When we write, we hold each memory in our hands, turn it, see past and present overlap.” The main component of Brooke’s Plan blends poetry and prose in a nonlinear, braided life-writing piece titled “As I Left It,” where prose rooted in childhood memories weaves into poetic forms that seek to collect and connect fragments. Their original works are supported by an essay reflecting on C.D. Wright’s idiosyncratic style and influence on their own experimental explorations. “What drew me to experiment with form and outside of conventional forms in my poetry and prose was the inadequacy of words alone to convey what I aim to express.”

“Memory, like a good poem, can be returned to again and again, yielding new meanings from new angles,” says Brooke Evans ’19, who completed their Plan in writing in December. “When we write, we hold each memory in our hands, turn it, see past and present overlap.” The main component of Brooke’s Plan blends poetry and prose in a nonlinear, braided life-writing piece titled “As I Left It,” where prose rooted in childhood memories weaves into poetic forms that seek to collect and connect fragments. Their original works are supported by an essay reflecting on C.D. Wright’s idiosyncratic style and influence on their own experimental explorations. “What drew me to experiment with form and outside of conventional forms in my poetry and prose was the inadequacy of words alone to convey what I aim to express.”

Perspective

Silencing the Most Vulnerable

By Nick Creel

In June 2018, five journalists working at the Capital in Annapolis, Maryland, were violently gunned down, and two others were injured. Only 48 hours before, far-right journalist Milo Yiannopoulos remarked to reporters that he “[couldn’t] wait for the vigilante squads to start gunning journalists down on sight,” and US President Donald Trump has repeatedly labeled the free press as “the enemy of the people.” While the gunman’s motives have been deemed more personal than political, any observer could connect the dots—the far right has been spouting anti-journalist rhetoric for decades.

When the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, one of the first actions the government took was to gain control over all media available to Germans. The party flooded their own newspapers and radio stations with anti-Communist rhetoric, then framed dissident journalists as traitorous Communists. With the general population filled with fear, it was simple for the government to imprison dissidents, destroy the offices of anti-Nazi newspapers, and, as the regime continued to gain power, kill any journalists who spoke against the regime.

In modern America, the government doesn’t have to lift a finger against journalists. Anti-journalism rhetoric shared by Trump, Yiannopoulos, and countless other far-right figureheads is striking fear and hatred into the hearts of sympathetic Americans across the country. Firearms flow freely, without restriction, and if enough angry Americans with guns believe that the free press is out to destroy America, who’s to say that they won’t take action?

Why would the far right be interested in suppressing journalism? Because without journalism, there is no one to reveal the atrocities committed against people of color, women, queer people, trans people, disabled people, or political dissidents. Without journalism, there is no one to hold fascists accountable to the rest of the world in hopes of stopping the continued destruction of human rights, not only in the US, but around the world. The far right wants its cultural and economic hegemony to continue, and removing journalists from the picture only makes that goal easier to obtain.

Allowing fear to control our lives is not the solution that will bring fascism to its knees. We must support one another throughout the struggle and continue to fight back against those who would like to keep us silent, both to ensure a safe future and to commemorate the fighters we’ve lost along the way.

Nick is a senior at Marlboro, completing a Plan of Concentration in computer science and writing, with a focus on interactive narratives. This editorial is excerpted and adapted from an essay originally posted on Cripple Magazine.

On and Off the Hill

Documenting Last Months on Potash Hill

Along with the sense of loss, grief, and confusion around Marlboro’s planned alliance with Emerson College, there has been an upwelling of concern about positively supporting Marlboro’s final months. This has prompted efforts by a group of students, faculty, and staff to launch a cohesive documentary project that will provide space for the community to reflect on this pivotal moment in the college’s history.

“This campus is a very special place that means so much to many people,” says Erelyn Griffin ’20, one of the students who has helped bring people together for the documentary effort. “In documenting we will not only pay homage to this place that we have called home, but provide a look into a moment of history where liberal arts colleges and opportunities for higher education are so vulnerable.”

The group is investigating and acting on several media projects, including video documentary, audio documentary, writing, and photography. Sam Harrison ’20 plans to include an element of documenting Marlboro’s last semester as part of his Plan in film and video studies, and visiting faculty Brad Heck ’07 will encourage Marlboro-focused projects in his spring class titled The Art of the Mini-Documentary. Several alumni are stepping up to do their own related projects, and have been urged to participate.

“It’s important to capture the reality of what it is like to be at a college campus that is closing, to hear from people who really care about where they are, to experience what people are going through,” says Brad. “It’s also a way of helping people process.”

“We are a part of the folk group of Marlboro College, and so much of our folk customs, traditions, and stories are tied to this specific place,” says Erelyn. “This project is as much in the interest of preserving our culture as it is about anything else. We must remember the Howland ghosts, the library mice, broomball!”

To help support or participate in this documentary effort, contact sharrison@marlboro.edu.

Campus Visits Promote Understanding

The November announcement of the alliance between Marlboro College and Emerson College has been followed by a series of visits by members of both campuses, helping to build relationships and a common understanding of the future of Marlboro. The first of these visits was on November 20, when five members of the Emerson leadership visited Marlboro to answer questions and get a feel for the mood of the campus around the proposed alliance.

The November announcement of the alliance between Marlboro College and Emerson College has been followed by a series of visits by members of both campuses, helping to build relationships and a common understanding of the future of Marlboro. The first of these visits was on November 20, when five members of the Emerson leadership visited Marlboro to answer questions and get a feel for the mood of the campus around the proposed alliance.

“Our students and you share some commonalities,” said Emerson President Lee Pelton, who addressed Town Meeting on behalf of the visitors. “They see in Emerson a place of magic, a place of creativity, a place where there are independent-minded people, and where students have agency. And my sense is that many of those characteristics are common to those of you who decided to come to Marlboro.”

Pelton expressed optimism that Marlboro students and faculty and their counterparts at Emerson could work together to create an academic program of excellence. In addition to attending Town Meeting, the visitors lunched with faculty, met with faculty committees, listened to senior Plan presentations, and concluded their visit by having tea with students to respond more specifically to their concerns.

That visit was followed with a trip by 40 students and faculty to Emerson’s Boston campus on November 24, to get a tour of campus facilities, meet some students, talk about curriculum, and see an ArtsEmerson production of An Iliad. This visit was facilitated by Marlboro life trustee and former staff and faculty member Ted Wendell, who has also been a longtime supporter of ArtsEmerson.

“This was a way of introducing to Marlboro some of the richness that Emerson has to offer and getting them on the actual campus,” Ted said in an interview with the Emerson student publication the Berkeley Beacon. “I think getting the two parties to get to know each other and start to understand the strengths and values of each other is the best way to have it be smooth and fruitful for both sides—to have this new relationship prosper.”

Building on these experiences, a group of Marlboro students invited students from Emerson College to enjoy part of Thanksgiving break on Potash Hill, and 10 students from Emerson came to Marlboro for two nights. They shared meals together, including Thanksgiving dinner, and explored and connected with the particular sense of place that is uniquely Marlboro.

Marlboro senior Adam Weinberg, who orchestrated the Thanksgiving visit, felt the brief trip brought some profound moments for shared reflection—from face to face engagement, to appreciation for Marlboro’s spirit of trust and open access to facilities, to theoretical questions of “Why liberal arts?” and “What does it mean to explore across fundamental questions?” The morning before returning to Boston, the students expressed great thanks for Marlboro’s sincere hospitality along with a heartfelt promise to hang out again, soon.

Emerson staff in admissions, student success, and other departments visited campus in January to meet with Marlboro students and discuss their potential transition to Emerson’s community. Students were also welcomed to Emerson for a group visit on February 14, and ongoing individual visits throughout the spring 2020 term, to experience the college’s community, offerings, and classes.

Emerson staff in admissions, student success, and other departments visited campus in January to meet with Marlboro students and discuss their potential transition to Emerson’s community. Students were also welcomed to Emerson for a group visit on February 14, and ongoing individual visits throughout the spring 2020 term, to experience the college’s community, offerings, and classes.

There have been several exchanges of faculty visits as well, starting with visits to Emerson in the week of December 2 and return visits to Marlboro in the week of December 16. These have been valuable opportunities to learn more about where Marlboro faculty will fit into Emerson’s programs and departments, how the curriculum for the new Marlboro Institute is expanding to embrace them, and what resources and facilities are available to them.

“As we enthusiastically shared ideas and goals, I wished our community could see the good will and compassion with which we were greeted by students, staff, and faculty,” said theater and gender studies professor Brenda Foley, following her first visit to Emerson. “Working with faculty peers at Emerson on our alliance convinced me that the coming together is far more than a pact ‘in name only.’ It promises an opportunity to carry with us intrinsic elements of a Marlboro education we hold dear, leave behind aspects that are no longer productive, engage with a more diverse cohort, and conceive of expansive and exciting new projects.”

The visits will continue to fill in the gaps between two cultures, between two campuses, and between idealistic hopes and concrete plans. “I feel fortunate to be making the journey with so many of my Marlboro faculty colleagues and students and look forward to the transformation to come,” added Brenda.

Working Groups Get Down to Details

Following quickly on the announcement of Marlboro’s alliance with Emerson College, working groups were formed to consider options and advocate solutions for key constituencies and interests, including students, faculty, staff, and the future of the campus. Most working groups took advantage of committees already engaged in advocating for these groups, and included trustees, faculty, staff, students, and, in the case of the campus working group, alumni. The student working group has the goal of charting the smoothest possible transition for students to Emerson or another institution of their choice, and of aligning student data with Emerson’s systems.

Following quickly on the announcement of Marlboro’s alliance with Emerson College, working groups were formed to consider options and advocate solutions for key constituencies and interests, including students, faculty, staff, and the future of the campus. Most working groups took advantage of committees already engaged in advocating for these groups, and included trustees, faculty, staff, students, and, in the case of the campus working group, alumni. The student working group has the goal of charting the smoothest possible transition for students to Emerson or another institution of their choice, and of aligning student data with Emerson’s systems.

The group is made up of the Dean’s Advisory Committee as well as Dean of Students Patrick Connelly, Dean of Admissions Fumio Sugihara, trustee and parent Susan Wefald, Director of Financial Aid Kristin Hielmenski, Registrar Cathy Fuller, IT Director Michael Riley ’09, and religion professor Amer Latif.

“We arranged four listening sessions with students in November and December, to allow students to voice their opinion regarding the proposed alliance and answer any questions,” said Patrick, who held the sessions. “They were well received, and helped lessen student anxiety about the alliance.” Student Life has increased social programming and events on campus in order to engage students in a healthy and productive way, and added additional counselors to the Total Health Center to support students feeling challenged by their next steps.

The working group has helped orchestrate visits between Marlboro students and Emerson staff and students (see page 20), and provided information about housing and financial aid to students and families transitioning to Emerson. In January the college announced that it would cover the difference in housing costs for students going on to Emerson, removing a huge barrier for many students. The working group has also supported the negotiation of transfer options with four other institutions—College of the Atlantic, Bennington College, Castleton University, and Saint Michael’s College— waiving application fees and other transfer requirements and offering comparable financial aid.

“We understand students have various preferences and needs in meeting their academic goals, and that for some students transferring to an institution other than Emerson may be their best path forward,” said Fumio. “Admissions will support any student interested in transferring to an institution other than the Marlboro Institute at Emerson.” The college has agreed to pay application fees for students transferring to other, non-partnered colleges.

The working group on faculty includes members of the Committee on Faculty, Curriculum Committee, and faculty and students from the Strategic Options Task Force, as well as Provost and Dean of Faculty Richard Glejzer and trustee Donna Heiland. This group has the task of clarifying curricular requirements for students and developing an advising program for transition to Emerson. Working with their counterparts at Emerson, they have been building a four-year program that incorporates significant aspects of Marlboro’s curriculum, including an emphasis on writing and individualized study that will draw upon Marlboro’s tutorial model.

“It has been heartening to see how Emerson faculty eagerly welcome the expertise of Marlboro faculty in designing and implementing a new four-year degree program that includes individualized study,” says Richard. “Marlboro faculty have been driving the conversation on the curriculum, while learning from their counterparts about Emerson students and the spaces they will be working in.” The working group presented a proposal to Emerson in February, which then needs to work its way through Emerson’s governance structure for final approval.

The working group on staff has the task of stewarding the staff through the transition, and supporting staff well-being during what is admittedly a difficult time. This group is made up of the Committee on Staff and the Benefits Committee, and also includes COO Becky Catarelli and trustee and alumni parent Kirsten Malone.

Based on the advocacy of this group, in December the board of trustees unanimously approved a severance policy for staff that was considered generous by almost any measure. The group has also been actively finding ways to support staff in terms of placement in other jobs after the Marlboro campus closes.

Based on the advocacy of this group, in December the board of trustees unanimously approved a severance policy for staff that was considered generous by almost any measure. The group has also been actively finding ways to support staff in terms of placement in other jobs after the Marlboro campus closes.

“We are thrilled with the unstinting severance policy adopted by the trustees, and it was only made possible by the vigilance of this group,” says Becky. “We realize that, of all constituents, the staff is most affected by this alliance and want them to know that we are doing all we can to soften the blow.”

Perhaps the group that has attracted the most attention and interest of other constituencies, including alumni and Marlboro townspeople, is the campus working group. The group is chaired by two alumni, Sara Coffey ’10 and Dean Nicyper ’76, and includes faculty, staff, and students as well as Alumni Council member Randy George ’93, Marlboro Town Selectman Jesse Kreitzer, and trustees Dick Saudek and Phil Steckler.

In an email to members of the working group, Sara Coffey, a Vermont state representative who served on the board of trustees for several years, said “Each of us has a deep connection to the college, and we know many of us are feeling a great loss, so this is a challenging task, but a very important one. The aim of this working group is to develop a process for gathering community input and proposals for the future use of the Marlboro College campus.”

“It sounds really simple, but as you can imagine, all the different factors that are involved in what happens on campus make it very complex,” says Nikolas Katrick ’07, MSM’16, Outdoor Program director and one of the staff representatives. “We’re trying to find great proposals that can utilize this campus and also possibly mesh together with other proposals. Anybody can submit proposals, but the working group isn’t going to workshop someone’s idea and make it viable. We don’t have the capacity to do that.”

Specifically, the working group has invited proposals for ownership and use of the Marlboro campus that will provide a significant benefit to the Marlboro community and result in a payment consistent with the campus fair market value. Any proposal must also be consistent with the terms of the Marlboro Music Festival lease and any amendments. The plan is to present the most viable proposals for review and approval by the Marlboro board of trustees, or by Emerson if they are presented after the merger.

“We have heard of widespread interest from various groups who are interested in finding some way to continue to have a managed trail network and preserve the Marlboro College Ecological Reserve,” says Sara. “These will be considerations as we move forward.” Each working group member has been collecting proposals from their respective constituents, and coordinating with state officials and counterparts at Emerson as necessary.

For more information about submitting a proposal, visit marlboro.edu/CWG. Proposals will be reviewed on a rolling basis and will be held in the strictest confidence.

Alumni Association Revival

After years of absence, the Marlboro College Alumni Association was revived last fall with the full support of the college, thanks to renewed passion among Marlboro’s alumni community and a core of committed alumni who took on the hard work of grassroots organizing. Given the possible transfer of Marlboro’s faculty, students, and pedagogy to the Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies at Emerson College, this alumni revival came not a moment too soon.

“During this crucial time for the college, we recognize the importance of coming together,” says an October statement from members of the interim council, which now includes Heather Bryce ’04, John Coakley ’02, Daniel Doolittle ’95, Randy George ’93, Cate Marvin DuPont ’93, and Jessica Taraski ’91. The group met with 27 alumni on campus for Home Days in September, and has heard from hundreds more since then through their website and social media presence.

“We consider ourselves an interdependent association,” says Daniel. “We are independent of the college, but collaborate with the administration and trustees to share the voice of their largest constituency.” Marlboro has about 5,000 alumni, and nearly 600 had opted in as members of the association as of January—more than 10 percent in four months—ranging in class year from 1959 to 2019.

The interim council plans to have open, democratic elections for council positions in 2020, and to work in concert with the college to support alumni as well as archive their rich Marlboro memories. In the meantime, the council has made great strides in forming committees and connecting with alumni, the college administration, campus community, and trustees—one member, Randy George, is on the Campus Working Group, and a November survey by the council highlighted alumni priorities.

“It’s an incredibly interesting time,” says Daniel. “At first we were just launching the foundation to engage alumni, now we are retooling to serve changing alumni needs. We have to organize toward a completely different reality.” The Alumni Association helped make the Drop Some Love on Campus campaign a success, for example, and spread the word on the open session at December’s trustee meeting, providing alumni and other constituents access to the trustees. “One of our most important purposes is to serve as some sort of memory archive, or memory vessel, of the Marlboro experience.”

“The association gives alumni a space, which has long been absent, to process the potential closure of the college or work for different possible futures,” says John Coakley ’02, another interim council member. “No matter what happens to the Marlboro name, or the campus on Potash Hill, the Alumni Association will be there to provide that home. Marlboro’s alumni will not disappear, and their memories will only become more important in the future.”

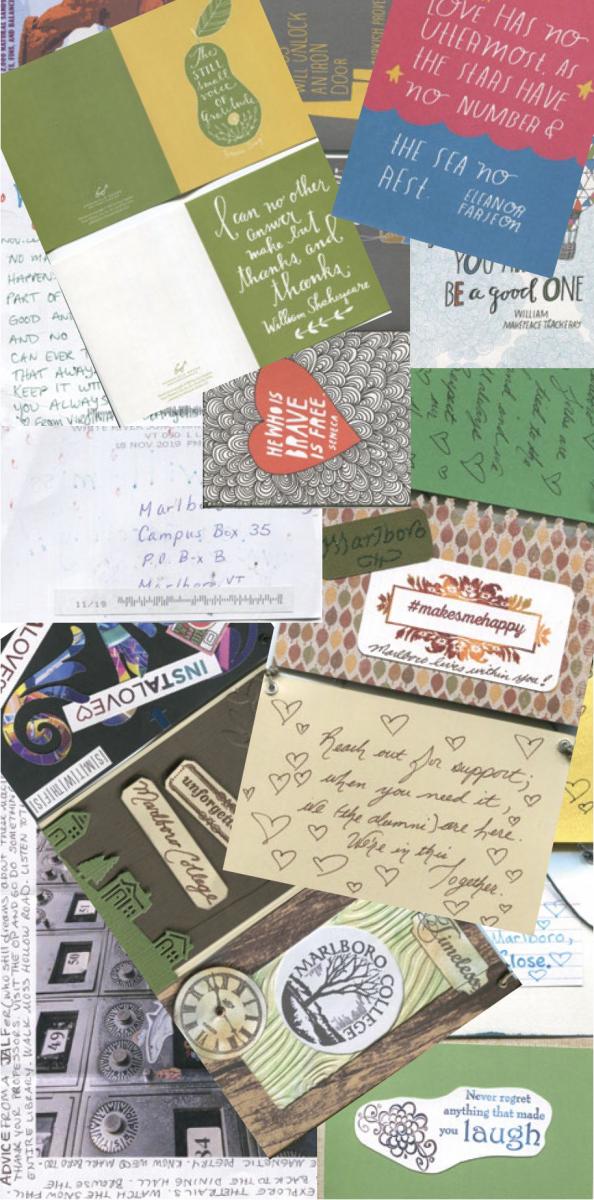

Alumni Drop Some Love

In November and December, just when it was needed most, the Marlboro College Alumni Association announced a Drop Some Love on Campus campaign, inspiring dozens of alumni to share their well-wishes and Marlboro stories with students, faculty, and staff. Postcards, handmade note cards, and photocopied photographs appeared on campus and were distributed by student collaborator Felix Bieneman ’21 and friends. Here is a small sampling of the bounteous love and deep Marlboro history.

In November and December, just when it was needed most, the Marlboro College Alumni Association announced a Drop Some Love on Campus campaign, inspiring dozens of alumni to share their well-wishes and Marlboro stories with students, faculty, and staff. Postcards, handmade note cards, and photocopied photographs appeared on campus and were distributed by student collaborator Felix Bieneman ’21 and friends. Here is a small sampling of the bounteous love and deep Marlboro history.

A Home Days to Remember

The Marlboro College campus was inundated with alumni and good vibes for Home Days 2019, September 27 through 29, an opportunity to remember, reflect, and support the college. Eager alumni came from as far away as Texas and California, and spanned over 50 graduation years, from 1968 to 2019.

The Marlboro College campus was inundated with alumni and good vibes for Home Days 2019, September 27 through 29, an opportunity to remember, reflect, and support the college. Eager alumni came from as far away as Texas and California, and spanned over 50 graduation years, from 1968 to 2019.

“It was incredible to see campus jam-packed with alumni,” says Maia Segura ’91, director of alumni engagement. The event raised over $6,000 for Marlboro, and provided a full measure of solidarity for this key constituency. “It was a ‘best of Marlboro’ day, and the love and support for our community has been overwhelming.”

Highlights included a packed house for the Alumni Dance Showcase in Whittemore Theater, featuring the work of nine alumni dancers at the height of their game, and standing room only in the dining hall for politics professor Meg Mott’s lecture on the First Amendment. A “Kevin Unplugged” session offered alumni the opportunity to hear directly from the college president about the status of merger negotiations, and to express their ideas and support. At the festive Saturday night dinner, Allison Turner MS’99 received the 2019 Roots Award recognizing her outstanding service to the Marlboro College community.

“I was very moved by the programming and energy on the Hill,” says alumna and trustee Heatherjean MacNeil ’02. “It was a stark reminder of why Marlboro is so deeply important to me, and of its ability to cultivate such an amazing community that is driven by talented and caring individuals.”

“I was very moved by the programming and energy on the Hill,” says alumna and trustee Heatherjean MacNeil ’02. “It was a stark reminder of why Marlboro is so deeply important to me, and of its ability to cultivate such an amazing community that is driven by talented and caring individuals.”

Find more photos on our flickr page. See a sampling from the Alumni Dance Showcase on Vimeo.

Alumni Get Crafty in Japan

A small group of alumni was preparing to embark on a two-week trip to Japan in May, led by Asian studies and history professor Seth Harter, before their plans were foiled by the coronavirus outbreak in Asia. Now they are setting their sights on running the trip, titled The Enigmatic Beauty of Japanese Craft, in 2021.

“Ever since the first round of Freeman Foundation– funded trips to Asia, I have been hearing from alumni wishing they could take part in such college-sponsored adventures,” says Seth. “Other colleges have been doing this for decades, but we will do it in a uniquely Marlboro way: relatively low budget, very small scale, personal encounters with brilliant, dedicated people,” says Seth.

While traveling through the heart of central Japan, participants will explore the question: how can contemporary crafts navigate between the realms of industry and fine art? They will encounter 1,300- year-old wooden temples, austere Zen rock gardens, traditional ceramics, and flamboyant textiles, exploring from the cosmopolitan hubs of Kyoto and Tokyo to the grass-thatched huts of mountain villages. The itinerary is inspired by Seth’s 2017 trip to Japan with Salvatore Annunziato ’18 (see Potash Hill Fall 2018), and his more recent sabbatical there in spring 2018.

“This trip will be an opportunity to build community, at a time when the community is feeling a bit besieged,” says Seth. “We have all been asking ourselves what parts of Marlboro will be able to endure the merger process. I think this is one thing that could flourish beyond next year, and I hope it can be reproduced by other people with other themes in other parts of the world.”

Campus Acknowledges Abenaki Homeland

In the week leading up to October 14, the first official Indigenous Peoples’ Day in Vermont, campus community members were encouraged by the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force to examine their own role in dismantling colonialism. To start with, they were asked to make a general practice of acknowledging the Sokoki (Western Abenaki) people in whose homeland Marlboro College stands.

“Land acknowledgments are often given at the beginning of public events, or in my case at the beginning of my courses,” says anthropology professor Nelli Sargsyan. “Their intention is to bring into our collective awareness the Indigenous people who have been living here and the histories of various kinds that we, as settlers, have inherited as a way of grounding.”

Land acknowledgement was one of several ways that the task force called on the Marlboro College community to observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Community members were also urged to do their own research to find out more about the Sokoki people and Abenaki people in general, their history, and what some of them are up to now. Further, they were encouraged to explore their own relationships to this territory, and how they came to be here.

“Our acknowledgement needs to come with a commitment, and not be something we do because it is trendy or to check a box of things progressive institutions do,” says Nelli. At Town Meeting she shared some of the recent history of this area and the impacts of colonialism, including the Vermont Eugenics Survey and systematic sterilization, and offered resources to learn more. “We each need to ask ourselves, ‘What intentions do I have to disrupt and dismantle colonialism beyond this land acknowledgement?’”

EV Charging Comes to Potash Hill

In September, Marlboro College installed an electric vehicle (EV) charging station in the admissions parking lot, a boon to students, faculty, staff, and visitors with electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles. This forward-thinking addition to campus is thanks to a Vermont State grant, as well as funds from an anonymous private donor that were dedicated to environmental stewardship and sustainability.

“Environmental sustainability is something Marlboro College has taken very seriously, from making dorms energy efficient to composting our food waste,” says chemistry professor Todd Smith, who served in the role of sustainability project manager last academic year. “The EV charging station is a very visible way of staking this claim, and encouraging the use of electric vehicles. Transportation is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gases in Vermont, so this is one small step toward reducing that component of our ecological footprint.”

Marlboro College was one of nine locations in Vermont that received awards from a $400,000 Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) Grant Program last year. The grant application was an example of the college’s shared governance in action, with Todd working with Environmental Quality Committee members Amber Hunt and Matt Ollis as well as Hillary Twining, director of corporate and foundation relations. The new EV charging station will be part of a statewide network of publicly available charging stations that drivers can locate through an app.

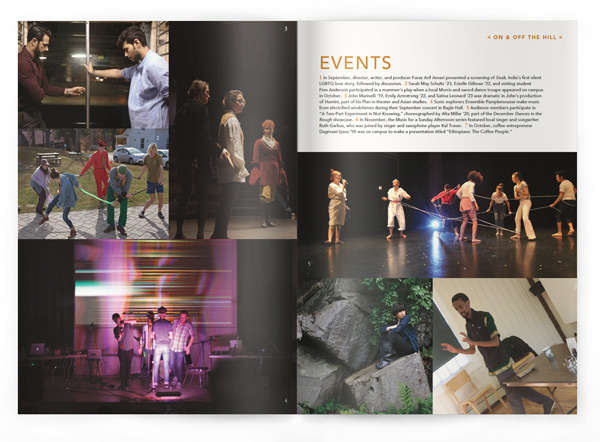

Events

1 In September, director, writer, and producer Faraz Arif Ansari presented a screening of Sisak, India’s first silent LGBTQ love story, followed by discussion. 2 Sarah May Schultz ’23, Estelle Gillman ’22, and visiting student Finn Anderson participated in a mummer’s play when a local Morris and sword dance troupe appeared on campus in October. 3 John Marinelli ’19, Emily Armstrong ’22, and Sativa Leonard ’23 wax dramatic in John’s production of Hamlet, part of his Plan in theater and Asian studies. 4 Sonic explorers Ensemble Pamplemousse make music from electrified windchimes during their September concert in Ragle Hall. 5 Audience members participate in “A Two-Part Experiment in Not Knowing,” choreographed by Alta Millar ’20, part of the December Dances in the Rough showcase. 6 In November, the Music for a Sunday Afternoon series featured local singer and songwriter Ruth Garbus, who was joined by singer and saxophone player Kal Traver. 7 In October, coffee entrepreneur Dagmawi Iyasu ’98 was on campus to make a presentation titled “Ethiopians: The Coffee People."

Focus on Faculty

FacultyQ&A

In October, before news about the alliance with Emerson had surfaced, Sativa Leonard ’23 sat down with dance professor Kristin Horrigan to talk about chemistry, contact improvisation, and heteronormativity. You can read the whole interview at potash.marlboro.edu/horrigan.

Sativa: What has been the most rewarding part of your work here at Marlboro?

Kristin: Definitely the work with the students. The deep relationships you form and how intimately you get to support someone in their growth—that’s very rewarding. There’s also the part where the students stretch us as faculty in a million directions. They cause us to study things, think about things, talk about things, and do things that we never would have thought to otherwise. That keeps the job from ever getting boring.

S: What do you like most about teaching here?

K: One of the things I love about teaching here is that students are following their passions, interests, and curiosities. Which means, most of the time when you have a student in class, they’re in your class because they want to be in your class, and that’s really beautiful.

S: What is the most challenging part?

K: Oh, workload. You know, in this community, we’re all here pretty much based on love, right? You get involved in the community, you care so much for your students, so you go the extra mile. Nobody tells you to not do more. You have to place your own limits.

S: Any new projects you’re excited about?

K: I just launched a new website. That was my summer project. I haven’t had a website for my professional dance work since I closed my dance company, Dance Generators, five years ago. It was time to launch my own site, reflecting the different branches of my work.

Visit Kristin’s site at kristinhorrigan.com. Photo by Jen Morris

In September and October, visual arts faculty member Amy Beecher presented a show of her work, titled Container Store Cantastoria, at New York City’s Hesse Flatow. In her exhibit, “printed-out paintings” were explored through cantastoria, an ancient and still-practiced method of performing paintings through song, sung by opera singer Melanie Long. Amy’s libretto borrows language from Hans Hofmann’s Search For the Real mixed with assembly instructions for Container Store shelving units. “Despite their disparate contexts, all of these texts champion the organization of space as a pathway for a better understanding of the self and its capacity to experience emotion and empathy,” says Amy. Learn more at amybeecher.studio/Container-Store-Cantastoria.

In October, anthropology professor Nelli Sargsyan organized a session called “Pursuing Collective Political Possibilities through Collaborations and Practices of Solidarity” with two of her Plan students, Alta Millar ’20 and Leni Charbonneau ’19. The session was part of the Engaging Anthropology Conference at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where they each presented on their work. In November Nelli participated in a Ms. magazine workshop for feminist scholars at the National Women’s Studies Association Annual Conference, in San Francisco, the aim of which was to help feminist scholars translate their research for popular press. Her poem “Academia-Dot-Edu Sends me Gifts, I mean, Notifications!” will be published in Feminist Anthropology, the journal of the Association for Feminist Anthropology.