Summer 2012

Editor’s note

If you are a college student, 65 years seems like a long time. But for a college it is just old enough to be past the angst and uncertainty of youth and into the considered confidence of a seasoned institution. This year, Marlboro is celebrating that milestone in many ways, most notably with our alumni reunion in May. In this issue of Potash Hill you can see some photos from that reunion, read what President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell has to say about innovation and find out what some alumni learned about learning at Marlboro.

With articles coming from many perspectives and disciplines, this issue bolsters the contention that time is relative, as well as precious. Commencement speaker Bill McKibben, the noted author and environmental activist, says that the earth has crossed a threshold to a new era of climatic instability in just the last couple decades. Alumnus Will Brooke-deBock puts a modern spin on Marxist theory, and writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard shows how history was unkind to both Native Americans and native orchids. Recent graduate Trevor Bowen illustrates how time and providence stand between something called a coronal mass ejection and technological disaster. As always, I welcome your responses and ideas, both relative and absolute, for future issues.

–Philip Johansson, editor

Taking Off the Moccasin Flower and Putting On the Lady’s Slipper

By Kyhl Lyndgaard

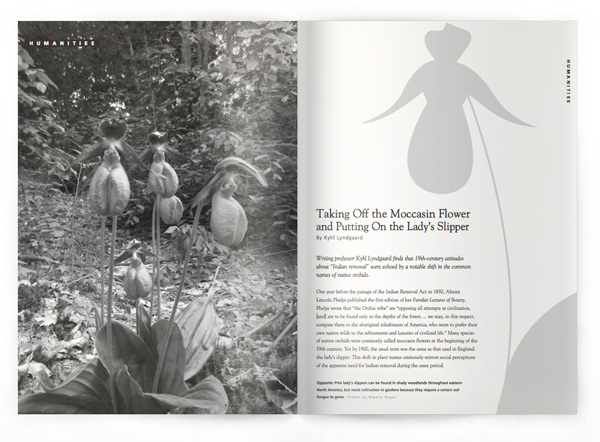

Writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard finds that 19th-century attitudes about “Indian removal” were echoed by a notable shift in the common names of native orchids.

One year before the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Almira Lincoln Phelps published the first edition of her Familiar Lectures of Botany. Phelps wrote that “the Orchis tribe” are “opposing all attempts at civilization, [and] are to be found only in the depths of the forest…. we may, in this respect, compare them to the aboriginal inhabitants of America, who seem to prefer their own native wilds to the refinements and luxuries of civilized life.” Many species of native orchids were commonly called moccasin flowers at the beginning of the 19th century. Yet by 1900, the usual term was the same as that used in England: the lady’s slipper. This shift in plant names ominously mirrors social perceptions of the apparent need for Indian removal during the same period.

The ways white Americans wrote about moccasin flowers during the 19th century—and the ways this earlier name slowly fell from common usage—illustrate how Indian removal was rationalized based on changes in the landscape. The moccasin flower was routinely used as a symbol representing Native Americans in discourse on federal policies of Indian removal. This selective use of botanical information allowed political sentiment about Indian removal to have an undue factual basis in nature study, and often led to the unwitting complicity of progressive writers.

William Cullen Bryant used his editorship at the New-York Evening Post as a platform to editorialize in support of parks and conservation, but nonetheless supported President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Bryant’s poetry often draws upon flowers, including the moccasin flower, to symbolize not only death in general, but also the inevitable extinction of Native American culture. In “The Maiden’s Sorrow” (1842), Bryant writes,

Far on the prairies of the west,

Far on the prairies of the west,

None who loved thee beheld thee die;

They who heaped the earth on thy breast

Turned from the spot without a sigh.

There, I think, on that lonely grave,

Violets spring in the soft May shower;

There, in the summer breezes wave

Crimson phlox and moccasin flower.

Bryant’s poetry suggests that Native Americans are already relegated to exile. His contemporary audience readily understood the many contemporary references and social attitudes in his writing.

In a later example, Susan Fenimore Cooper made a valuable comparison between weeds and native flowers in Rural Hours (1850):

The wild natives of the woods grow there willingly, while many strangers, brought originally from over the Ocean, steal gradually onward from the tilled fields and gardens, until at last they stand side by side upon the same bank, the European weed and the wild native flower.

These foreign intruders are a bold and hardy race, driving away the prettier natives. It is frequently remarked by elderly persons familiar with the country, that our own wild flowers are very much less common than they were forty years since…. The moccasin-flower abounded formerly even within the present limits of the village.

Cooper opens this passage by linking disturbed ground to the ability of weeds to take hold where native plants formerly made up the entire population. She specifies that the weeds are European, and constitute a “bold and hardy race” that continues to displace the native population. Cooper claims that this is a “mingled society” in which examples of both European and North American origins can potentially “stand side by side.” The inevitability of Indian removal is not a foregone conclusion for her, despite the elegiac nature of her father’s novel Last of the Mohicans.

Fascinating corollaries were developed in response to the increasing scarcity of native orchids as the 19th century progressed. Some argued that the moccasin flower could be domesticated, a claim connected to the opening of the first Indian boarding schools. Laura Sanford explained in an 1891 horticultural article that “if we are to possess the representatives of this fair and fascinating race, which belong to us as the native offspring of American soil, we must guard them from destruction in their favorite haunts.” Words such as “possess” support assimilation as a perceived necessity. Sanford also expresses a newly found romantic pride in America’s native populations. Her article is conspicuously devoid of words identifying the subject as a plant and could be mistaken for the words of progressive reformers. Sanford ultimately asserts that the moccasin flower dies from “homesickness” after a year or two. As seen by death rates upon removal to reservations or boarding schools, Native Americans also suffered terribly upon the loss of their homes.

Still, this argument found favor with writers who were sympathetic to Native Americans and reluctantly felt that assimilation was the best hope for ensuring human rights. Lydia Maria Child contrasted wildflowers with domestic plants to grapple with questions of Indian removal. Her short story “Willie Wharton” examines the life of a boy who was taken captive by Indians and returned later in life to his biological family with a Native American bride. His well-meaning family, while they give space to the couple to assimilate, compare plants to ethnic groups. Child writes that “the wild-flowers of the prairie were supplanted by luxuriant fields of wheat and rye,” while the character Uncle George remarks that Willie’s native bride is as “‘bright as the torch-flower of the prairies’” and that “‘wild-flowers, as well as garden-flowers, grow best in the sunshine.’” Child—and many other progressive and transcendentalist writers—promoted assimilation through flower analogies.

Elaine Goodale Eastman’s 52-line poem “Moccasin Flower” includes lines pointing to a more nuanced relationship among whites, Native Americans and native orchids:

Elaine Goodale Eastman’s 52-line poem “Moccasin Flower” includes lines pointing to a more nuanced relationship among whites, Native Americans and native orchids:

Yet shy and proud among the forest flowers,

In maiden solitude,

Is one whose charm is never wholly ours,

Nor yielded to our mood:

One true-born blossom, native to our skies,

We dare not claim as kin,

Nor frankly seek, for all that in it lies,

The Indian’s moccasin.

Eastman describes in code the tension between North American inhabitants at the time. Published in the well-received poetry collection In Berkshire with the Wildflowers (1879) when Eastman was only 16, the poem clearly articulates the resistance of the “native,” rather than relying upon the more common theme of vanishing. At this point in the poem Eastman pivots slightly, spending the next 10 lines on the difficulties of finding the moccasin flower. She ends the poem on a strange note:

With careless joy we thread the woodland ways

And reach her broad domain.

Thro’ sense of strength and beauty, free as air,

We feel our savage kin,—

And thus alone with conscious meaning wear

The Indian’s moccasin!

In these final lines of the poem, Eastman places the writer—and reader—in the shoes of Native Americans. The “careless” quality of the poem’s joy suggests an irresponsible hope to escape civilization. After first claiming the moccasin flower is off-limits, Eastman is strangely unable to stop herself from completing the journey. Her own life followed a fascinating parallel with this poem: she taught Native American children in South Dakota, marrying Charles Eastman shortly after assisting him in nursing the victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Elaine likely made significant contributions to Charles’ books, which include Indian Boyhood.

Writing at the end of the 19th century, Mabel Osgood Wright expressed regret over these changes to the land and its native inhabitants: “Ladies’ Slipper is not a word in keeping with Hemlock and Beech woods, but the word Moccasin throws meaning into the black shadows and brings to mind the stone axe and flint arrow-heads found not long ago.” When Wright spies a moccasin flower along a roadside, she picks it, but only because of worries that someone else will see it and “follow the trail into the woods, and make the whole colony prisoners.” While Wright’s knowledge of Native American culture is somewhat superficial, she is insistent on the importance of local knowledge. Wright argues to keep the name moccasin flower, stating that when “a common name, spicy with the odor of the new western world, is given to a plant, I think we should keep it…and call our little group of inflated pouched Orchids, Moccasin Flowers, instead of Ladies’ Slippers, as Britton does, a general title which confuses their personalities with the European species.” However, her argument is belated, as the common name of lady’s slipper had by then all but supplanted the earlier usage of moccasin flower.

Despite persisting worries about captivity on the frontier, by the end of the 19th century native orchids with slipper-shaped pouches were commonly called lady’s slippers, rather than moccasin flowers. The removal of Native Americans from lands that white settlers desired—especially those east of the Mississippi, which correspond with the primary natural range of these orchids—was all but complete. Nonetheless, a more positive parallel may be made today: Native Americans were and are still very much present, as are many species of moccasin flowers, despite relentless attempts to destroy, displace and domesticate. A final example that explains why using moccasin flowers as a symbol for Native Americans was a problem can be plucked from Child’s prologue to “Willie Wharton.” She writes: “Would you like to read a story which is true, and yet not true? The one I am going to tell you is a superstructure of imagination on a basis of facts.”

Kyhl Lyndgaard teaches writing at Marlboro, with a focus on environmental studies and literature. He is working on an anthology of essays, fiction and poetry tentatively entitled Currents of the Universal Being: Explorations in the Literature of Energy.

The essence of orchids

While orchids symbolize changing attitudes for Kyhl, they quite literally changed the life and livelihood of Don Dennis ’82. After moving to England and trying a sustainable timber business, Don began importing flower essences for healing purposes. “One of our early suppliers was a woman in California who was making essences with orchids grown in her greenhouse,” said Don, who now lives in Scotland and is the author of Orchid Essence Healing. “Like T. Wilson with poetry, or Audrey Gorton with Shakespeare, this woman communicated a tremendous passion for her subject: it was then that orchids caught my notice for the first time.” Don bought his first small orchid (a Phragmipedium hanne popow), and this led to a second, and soon he had to build a greenhouse to house them all. Visit www.healingorchids.com to learn more. Photo: Fruits of love orchid, by Don Dennis

While orchids symbolize changing attitudes for Kyhl, they quite literally changed the life and livelihood of Don Dennis ’82. After moving to England and trying a sustainable timber business, Don began importing flower essences for healing purposes. “One of our early suppliers was a woman in California who was making essences with orchids grown in her greenhouse,” said Don, who now lives in Scotland and is the author of Orchid Essence Healing. “Like T. Wilson with poetry, or Audrey Gorton with Shakespeare, this woman communicated a tremendous passion for her subject: it was then that orchids caught my notice for the first time.” Don bought his first small orchid (a Phragmipedium hanne popow), and this led to a second, and soon he had to build a greenhouse to house them all. Visit www.healingorchids.com to learn more. Photo: Fruits of love orchid, by Don Dennis

Weathering Solar Storms

By Trevor Bowen ‘12

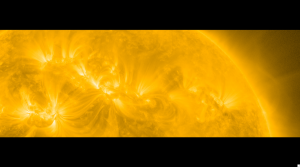

If you think the extreme weather patterns associated with climate change will put a wrench in our lifestyles, consider what a coronal mass ejection spewing plasma toward earth might do.

During a series of large solar storms in 2003, utility companies in Sweden reported that strong electric currents caused problems with transformers and even a system failure and subsequent blackout. These same storms temporarily disrupted the activities of approximately 59 percent of NASA missions. Clearly, our increasing global reliance on technology has introduced a practical need to understand the relationship between our earth and sun in new ways.

My interest in solar physics originated from a summer internship at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, where I took on a research project focusing on observations of solar flares—enormous bursts of electromagnetic activity from the sun that extend millions of miles into space. The resulting research and background theory became the focus of my Plan of Concentration work at Marlboro. The discipline of solar physics aims to develop our knowledge of the events that can cause such detrimental effects as the ones observed in 2003. Methodical observations, like those that are the subject of my research, are among the best ways to understand the dynamics of the sun and their potential impacts on earth.

While we casually conduct our lives here on earth, the sun emits a constant stream of energetic, charged particles into interplanetary space, including in our direction. Generally, the earth’s magnetic field acts to catch and deflect these particles, protecting the atmosphere (and us) from excessive exposure to this solar wind. At times, however, eruptions in the sun’s atmosphere can invigorate the solar wind such that it becomes violent enough to penetrate our protective shield. The effects are noticeable to us at high latitudes in the form of auroras, such as the northern lights; in the worst cases these storms can impact sensitive technological equipment.

While we casually conduct our lives here on earth, the sun emits a constant stream of energetic, charged particles into interplanetary space, including in our direction. Generally, the earth’s magnetic field acts to catch and deflect these particles, protecting the atmosphere (and us) from excessive exposure to this solar wind. At times, however, eruptions in the sun’s atmosphere can invigorate the solar wind such that it becomes violent enough to penetrate our protective shield. The effects are noticeable to us at high latitudes in the form of auroras, such as the northern lights; in the worst cases these storms can impact sensitive technological equipment.

In 2010, NASA launched the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) to replace and improve upon existing observational tools. The SDO consists of three instruments that function together to provide an incredibly advanced and robust tool to study solar phenomena. My research focuses on one of the three instruments, the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA), which provides images of the full sun at 10 different wavelengths with exposures taken every 10 seconds. That’s 3,600 images an hour. When all is said and done, AIA generates slightly under two terabytes of information—or 2,000 gigabytes, enough to fill four MacBooks—each day. Needless to say, storing and analyzing these data is quite the task. Ironically, the size and complexity of the available data pose one of the greatest challenges to developing comprehensive theories of solar phenomena: observations have advanced to a level of depth that theories struggle to keep pace and accurately explain every minute detail.

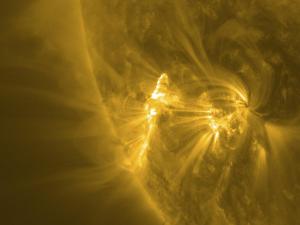

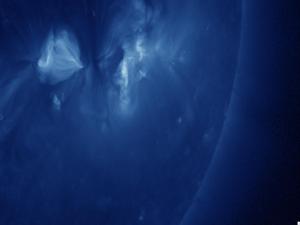

The primary concern of AIA is with light originating from the corona, the highest and hottest part of the solar atmosphere, with characteristic temperatures above a million degrees. Most of the light emitted by the corona is not visible to the naked eye; that’s why we can’t just look up and see it. The corona only becomes apparent to the eye during solar eclipses when the majority of the sun is blocked out—it stands out like a halo. For its observations, AIA relies on radiation in the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) wavelengths, which fall somewhere between an x-ray and a tanning booth. The solar photosphere, a lower layer of the solar atmosphere that emits the vast majority of the sun’s light we see every day, does not emit in these wavelengths because of its lower temperatures. Images of the sun taken in EUV wavelengths thus correspond strongly with emissions from the corona.

Our interest in the corona arises for two reasons. First, observations show that solar storms capable of causing detrimental effects are correlated with eruptions of the solar atmosphere that spew coronal “plasma” into interplanetary space. Plasma is a state of matter somewhat like a gas; the key difference, however, is that its constituent parts (negatively charged electrons and positively charged nuclei) are stripped apart from each other. The sun is mostly composed of extremely hot hydrogen and helium at temperatures so high that this disassociation occurs.

Our interest in the corona arises for two reasons. First, observations show that solar storms capable of causing detrimental effects are correlated with eruptions of the solar atmosphere that spew coronal “plasma” into interplanetary space. Plasma is a state of matter somewhat like a gas; the key difference, however, is that its constituent parts (negatively charged electrons and positively charged nuclei) are stripped apart from each other. The sun is mostly composed of extremely hot hydrogen and helium at temperatures so high that this disassociation occurs.

Solar eruptions of plasma, called coronal mass ejections (CMEs), are frequently associated with other events known as solar flares. Closely monitoring the corona can help scientists understand when and why CMEs and flares occur. Ideally, we would like to be able to understand the corona and its workings to the point where transient solar phenomena can be anticipated—just like predicting a blizzard over Potash Hill in the middle of February.

Secondly, the corona provides a window into the inner workings of the sun. The sun is a dynamically evolving system with many layers; however, because the sun is opaque, direct imaging of the solar interior is not possible. It can take hundreds of thousands of years for radiation released through nuclear processes in the sun’s core to escape through its surface. Thus, scientists have historically had to work backwards from observations of the solar surface and atmosphere to study the nature of those interior physical processes. Our understanding of the solar magnetic field, for example, is primarily built on observations of the solar surface.

Magnetic fields are the primary culprits in most solar activity, and particularly relevant to our discussion of coronal eruptions. Essentially, the interior of the sun is made of free charged particles, or plasma as mentioned above. Like the earth, the sun rotates on its axis; accordingly, this rotation requires the motion of a huge mass of charged particles. One of the first principles in dealing with magnetism is that moving charges create magnetic fields. In the case of the sun, the massive amounts of moving charges create massive magnetic fields; this effect is called the solar dynamo. Over time, this magnetic field can bubble up through the solar surface into the atmosphere through convective processes—analogous to a single spaghetti noodle boiling up to the top of a pot of water.

The catalyst for solar flares and CMEs is usually some sort of instability in the configuration of the magnetic field. In such cases, the magnetic field rapidly restructures itself to regain a stable footing, releasing immense amounts of energy in the process, which can in turn power a flare or CME. Understanding the physical conditions that lead up to eruptive events, such as the initial magnetic field configuration, is crucial to developing theories of these phenomena. Observations of the corona made by instruments like AIA make this science possible. Furthermore, these same observations provide a window into the workings of the solar interior, allowing for a complete and clear scientific narrative of our sun.

The catalyst for solar flares and CMEs is usually some sort of instability in the configuration of the magnetic field. In such cases, the magnetic field rapidly restructures itself to regain a stable footing, releasing immense amounts of energy in the process, which can in turn power a flare or CME. Understanding the physical conditions that lead up to eruptive events, such as the initial magnetic field configuration, is crucial to developing theories of these phenomena. Observations of the corona made by instruments like AIA make this science possible. Furthermore, these same observations provide a window into the workings of the solar interior, allowing for a complete and clear scientific narrative of our sun.

In early March 2012, we observed one of the largest flares to occur in the current solar cycle, certainly the largest since I have been collecting data. Associated with this flare was a significantly sized CME directed straight at earth, an event heralded by newspapers and other media that predicted disruptions to flights, GPS systems and power grids. Due to the magnetic orientation of the storm, the effects of the CME’s impact were minimized by earth’s magnetic field. However, this event demonstrates the reality of these eruptions and their potential impact on our world—in this case little more than a brief interruption in the weekly news cycle of a slow presidential primary season. If the magnetic field of the storm had been aligned slightly differently, the impact would have been quite noticeable.

Trevor Bowen graduated in May with a degree in physics and a Plan of Concentration focusing on theoretical foundations, mathematical and computational principles and the process of scientific research.

The art of programmed objects

Aaron Evan-Browning ’12 used his Plan of Concentration to explore “the vocabularies of sculpture and computer science to make interactive objects.” “I see computer science more as a tool to make interesting things,” said Aaron. “I make things to satisfy my curiosity, to learn how things work and because I can’t help myself.” His impulsive creations resulted in a show in Drury Gallery that included, among other marvels, a set of computerized gnashing teeth and a children’s “Sing ‘n Smile Pals” toy, which he rewired in a process called circuit-bending to make sounds that would alarm most kids. Perhaps his most intriguing object is called “Eyebrow Switches,” a headband that creates seven different notes based on brow-bending facial expressions. “I have some of the best eyebrow control of anyone I know,” said Aaron.

Aaron Evan-Browning ’12 used his Plan of Concentration to explore “the vocabularies of sculpture and computer science to make interactive objects.” “I see computer science more as a tool to make interesting things,” said Aaron. “I make things to satisfy my curiosity, to learn how things work and because I can’t help myself.” His impulsive creations resulted in a show in Drury Gallery that included, among other marvels, a set of computerized gnashing teeth and a children’s “Sing ‘n Smile Pals” toy, which he rewired in a process called circuit-bending to make sounds that would alarm most kids. Perhaps his most intriguing object is called “Eyebrow Switches,” a headband that creates seven different notes based on brow-bending facial expressions. “I have some of the best eyebrow control of anyone I know,” said Aaron.

Winter Coat by Day: Student Poetry

Joanna Moyer-Battick

White Bread

White Bread

tastes like duck

on the water.

Goodbye

I move out

slowly, book

by book.

Winter Coat by Day

but when I get up to pee in the night,

the shadow of a man

bending to pull up his boots.

Lost

In the ocean:

my pinky toe nail.

It tore from my foot

like paper and I never saw it again

except maybe once

in the glassy smile of a fish.

Like Cilantro

You’re one pinch in the room

and I can taste you

the rest of the day.

Trevor Rickenbrode

The Lake

We grew up on this beach,

and we’re still here,

limping and lingering

beneath whoever touches us.

I wade into the lake, and behind me

bodies gather

in feral clusters inside the grotto

of moonlight that offers its forgiveness.

I go out a distance

and float holding an island rock,

feeling the cheeks

of childhood.

On the shore,

my friends throw

jars full of fire into

God’s mouth.

Their song is love.

Anna Blackburn

Ensenada

The streets are packed sand. The sidewalks

are bare boards. Folded alleyways lead nowhere

but into themselves. The men who speak English are the ones

not to talk to.

The man at the bar will buy drinks for my friends all evening, because

I have blonde hair. He kisses the figure of Jesus

hanging from a chain around his neck. “I love Jesus,

do you love Jesus?” A skinny dog sticks its head

through the open door. My friends are laughing

too loudly. He asks again, holding

the gold crucifix up to my face. It catches

all the brass light in the room, obliging

regard, like a headache. “Yeah,” I shrug, wincing, sliding down

off my stool. Something in his red eyes

comes to. “Where are you going,” he demands. I point to the dog,

which has disappeared.

Reflections: Seniors Exhibit Their Work

Annie Malamet studied empowerment through the paintings of Sofonisba Anguissola, the Italian Renaissance artist, and prepared an exhibit of video art using martyr iconography to investigate themes of self-possession. “I use medieval and Renaissance martyr imagery to discuss issues of sexual violence and its place in the larger context of fine art as well as pop culture,” said Annie. “Borrowing iconography from paintings of Christian martyrs, I have re-created these images in the form of live-action vignettes.”

Annie Malamet studied empowerment through the paintings of Sofonisba Anguissola, the Italian Renaissance artist, and prepared an exhibit of video art using martyr iconography to investigate themes of self-possession. “I use medieval and Renaissance martyr imagery to discuss issues of sexual violence and its place in the larger context of fine art as well as pop culture,” said Annie. “Borrowing iconography from paintings of Christian martyrs, I have re-created these images in the form of live-action vignettes.”

Willie Finkel received a degree in American studies, with a focus on curatorial studies and ceramics. He complemented his study of the Civil War with an exhibit featuring art from Marlboro ceramics professors and students over the years, including his own, shown here. Willie said, “I believe that our relationship to happiness, joy and beauty can accentuate our understanding of the past just as much as tragedy and sadness. So I tried to harness one of those qualities, our sense of beauty, to connect people to the past.”

Zach Parks used visual arts and philosophy to investigate the links between machines, technology and art. “In my work, I aim to explore relationships, actions and attitudes both human and mechanical,” said Zach. “A machine is a collection of parts working together to perform some sort of action, but may also be considered a series of abstract functions, or a group of mechanical relationships from which the final action emerges.” This piece, called “Cranes,” was one of several in Zach’s Drury Gallery exhibition.

Nick Rouke, who received a degree in visual arts, explored concepts of time, loss and absence through photographic work, including a series of portraits of his fellow students. “Once I started to understand how I felt and accepted that I wouldn’t ever be able to answer some questions, I started making work that was more a reflection of my perspective rather than dramatic statements that are trying too hard to be profound declarations of truth,” said Nick.

Nick Rouke, who received a degree in visual arts, explored concepts of time, loss and absence through photographic work, including a series of portraits of his fellow students. “Once I started to understand how I felt and accepted that I wouldn’t ever be able to answer some questions, I started making work that was more a reflection of my perspective rather than dramatic statements that are trying too hard to be profound declarations of truth,” said Nick.

Unalienated Labor and the Gameful Life

By Will Brooke-deBock ’87

Will Brooke-deBock took (in his words, “weaseled”) the opportunity to participate in Jerry Levy’s Classical Sociological Thought class last semester, 25 years after taking it for the first time. Here he shares his ruminations about what Karl Marx might make of Super Mario Brothers.

In the Marlboro tradition and practice of sociology, theory is never enough. Students are encouraged to apply and test theory against empirical realities. They are challenged to examine the veracity of the theory in terms of historical, social, psychological and cultural forces and their impact on the lives of real people. If the theory is found wanting or the social milieu surprising, the student is encouraged to sharpen or modify his or her analytical approach to the topic at hand. In this case the topic is online gaming, something that didn’t even exist the last time I read Thorstein Veblen’s 1899 classic, The Theory of the Leisure Class, let alone when he wrote it.

Consider the facts: (1) all of the classical sociological theorists have been dead for at least 80 years, (2) the majority of the major theorists were white, and (3) most of them were men—yes, classical sociological thought is the study of dead white guys. Actually, to be fair, the Marlboro tradition of sociological theory does teach theoretical approaches that include women and African-American writers, and certainly is open to many voices beyond the classical canon. Nevertheless, classical sociology thought needs to be considered against the historical and social realities of the 21st century if only because the world of Marx, Weber, Veblen and others described has continued to evolve or, at least, change.

One can imagine that the second decade of the 21st century would prove an interesting time for the study of the theories of Karl Marx, the famed German philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist. Today we have the Occupy Wall Street movements, the Arab Spring and various student protests that have emblazed “pepper spray” as a social meme and cultural terror on our collective conscience. Even the Harvard Business Review, arguably the representative of intellectual pursuit in the world of business, has gotten into the action with an article titled “Was Marx Right?,” a surprisingly balanced account of some of Marx’s criticisms of capitalism.

Yet, even as activists take to the streets, even as intellectuals discuss the implications of dissent in our times, large segments of the world’s population are engaged in activities that, at first glance, seem to be the polar opposite of this political phenomenon, namely: “gaming.” Although it’s not quite 99 percent, an astounding 183 million people in the United States identify themselves as active gamers. Internationally, the online gamer community includes 105 million in India, 100 million in Europe, 200 million in China and 10 million in Russia. It’s fair to say that, worldwide, there are millions and millions of people engaged in what many would consider frivolous, non-productive and escapist activities.

Sociology professor Jerry Levy talks about gaming and other social media not as just a fad or a trend, but rather, in the Durkheimian tradition, as a “social fact.” “You can’t deny it,” Jerry said, and this is coming from someone who may be one of the least competent users of digital technology I have ever known. “That means that whether you embrace it or not, you and society are being shaped by it. That’s what a social fact is; it is rock solid, whether you choose to embrace it or reject it.”

Considering the work of Karl Marx in light of the fact that gaming is a growing social phenomenon in the 21st century, one might easily coin a phrase like “World of Warcraft is the opiate of the masses”—or substitute “Halo,” or “Super Mario Bros.” Apparently, the gaming opium dens of the 21st century have a lot of vices from which to choose. I have to admit that this is a tempting concept—especially when I have to almost crowbar my 12- and 8-year-old sons from the various screens they sometimes seemed glued to.

Tempting, but probably wrong.

In Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World, game designer Jane McGonigal shares interesting statistics and empirical analyses that put gaming in a more positive light. Like many similar books (Jonah Leher’s How We Decide and Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows spring to mind), the main theoretical orientation is in the realm of neurochemical processes. McGonigal posits that there is a sense among gaming communities that “Reality, compared to games, is broken.”

“Reality isn’t engineered to maximize our potential,” writes McGonigal. “Reality wasn’t designed from the bottom up to make us happy.” Ultimately, games make us happy and, as she argues, can actually change the world, because they leverage the neuronal and chemical processes of the brain that make us happy. Maybe that opium metaphor is not so far off, after all.

But for the social philosopher and theorist, one needs to dig a little deeper. Let us first consider Marx, the young Marx of the Economic Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. These are the writings that are often thought to establish Marx as a humanist, and, indeed, were important to the new left during the 1960s. Here we are introduced to Marx’s concept of alienated labor. Marx writes:

This fact expresses nothing but this: the object which labor produces—the product of labor—confronts it as an alien being, as a power independent of the producer…. [T]his realization of labor appears as the loss of reality of the worker, objectification appears as the loss of the object and bondage to it.

It appears that Marx, too, considered reality as flawed. For Marx, labor is alienated in the following conditions: it is external to the worker; it is not voluntary, but coerced; and it is not his or her own, but somebody else’s. In The German Ideology, Marx describes a scenario of an unalienated laborer:

…while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity, society regulates the general production and this makes it possible for me to do one thing to-day and another to-morrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

I have to admit that when I was first introduced to Marx in the 1980s, it was hard to read passages like this without thinking of “back-to-the-land” communards living together in intentional communities—sometimes with the worst stereotypes in mind. The concept of alienated labor rang true to me, but the alternatives of what unalienated labor would really be like rang flat and hollow.

But consider McGonigal’s four defining traits of a game: a goal, giving the game a sense of purpose; rules, which guide the way one can reach one’s goal and, by definition, foster creative and strategic thinking; a feedback system, so you always know how you are doing; and voluntary participation—it wouldn’t be a game if you had to play it. McGonigal also cites non-essential traits of some games, including interactivity, rewards, competition and winning. Even with this abbreviated list, one gets the sense that we’re not describing the mechanisms of a multi-billion-dollar escapist industry, but something meaningful, purposeful and profoundly human.

She boils it down to this: “Games make us happy because they are hard work that we choose for ourselves, and it turns out that almost nothing makes us happier than good, hard work.”

I have not found a better contemporary conceptualization of unalienated labor in the 21st century. With or without intending to, McGonigal has turned the concepts of work and play on their heads, challenging us to reconsider the importance of games and a “gameful life.” Her work has opened up the discourse about meaningful work to many voices and perspectives, including those of the classical sociological theorists.

After earning his degree in sociology, Will Brooke-deBock went on to gain a master’s degree in Internet strategy management at Marlboro College Graduate School, becoming the college’s first dual graduate in 1998. Will has worked for many years at Kaplan University, where he is now a curriculum designer. He is also an independent provider of digital media education through his blog, innovationslab. wordpress.com.

Reflecting on terrorism

Far from the benign worlds of online gaming, “real” life has never been the same since September 11, 2001. Jack Rossiter-Munley ’12 devoted his Plan of Concentration to the cultural and political impact of the terrorist attacks, including co-teaching a course called After 9/11. “I noticed that whenever people found out what I was studying their first instinct was to tell me about their personal experiences on the day and offer their opinions on what came after,” said Jack. “I realized that it would be interesting to capture some of these personal experiences and match them up with the academic voices that I had been interacting with.” In his Plan, Jack explored how 9/11 was a transformational event in world politics and examined critical responses to the attacks.

Far from the benign worlds of online gaming, “real” life has never been the same since September 11, 2001. Jack Rossiter-Munley ’12 devoted his Plan of Concentration to the cultural and political impact of the terrorist attacks, including co-teaching a course called After 9/11. “I noticed that whenever people found out what I was studying their first instinct was to tell me about their personal experiences on the day and offer their opinions on what came after,” said Jack. “I realized that it would be interesting to capture some of these personal experiences and match them up with the academic voices that I had been interacting with.” In his Plan, Jack explored how 9/11 was a transformational event in world politics and examined critical responses to the attacks.

On & Off the Hill

This issue celebrates Marlboro's 65 years, including a look at how the college has changed and what some teachers learned about learning while they were here. We also say farewell to writing professor Laura Stevenson, join some students on their trip to Mexico City and see what went down at the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium this year.

This issue celebrates Marlboro's 65 years, including a look at how the college has changed and what some teachers learned about learning while they were here. We also say farewell to writing professor Laura Stevenson, join some students on their trip to Mexico City and see what went down at the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium this year.

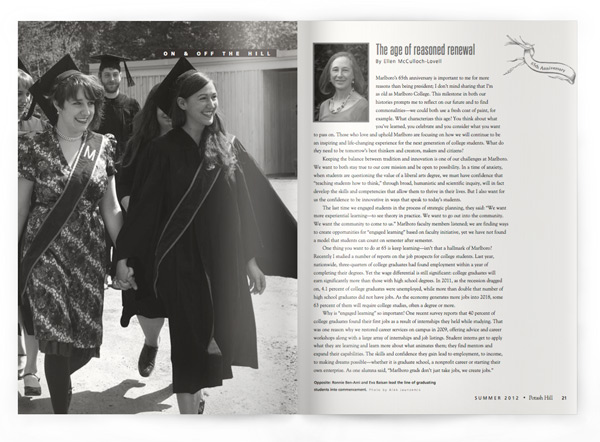

The age of reasoned renewal

By Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

Marlboro’s 65th anniversary is important to me for more reasons than being president; I don’t mind sharing that I’m as old as Marlboro College. This milestone in both our histories prompts me to reflect on our future and to find commonalities—we could both use a fresh coat of paint, for example. What characterizes this age? You think about what you’ve learned, you celebrate and you consider what you want to pass on. Those who love and uphold Marlboro are focusing on how we will continue to be an inspiring and life-changing experience for the next generation of college students. What do they need to be tomorrow’s best thinkers and creators, makers and citizens?

Marlboro’s 65th anniversary is important to me for more reasons than being president; I don’t mind sharing that I’m as old as Marlboro College. This milestone in both our histories prompts me to reflect on our future and to find commonalities—we could both use a fresh coat of paint, for example. What characterizes this age? You think about what you’ve learned, you celebrate and you consider what you want to pass on. Those who love and uphold Marlboro are focusing on how we will continue to be an inspiring and life-changing experience for the next generation of college students. What do they need to be tomorrow’s best thinkers and creators, makers and citizens?

Keeping the balance between tradition and innovation is one of our challenges at Marlboro. We want to both stay true to our core mission and be open to possibility. In a time of anxiety, when students are questioning the value of a liberal arts degree, we must have confidence that “teaching students how to think,” through broad, humanistic and scientific inquiry, will in fact develop the skills and competencies that allow them to thrive in their lives. But I also want for us the confidence to be innovative in ways that speak to today’s students.

The last time we engaged students in the process of strategic planning, they said: “We want more experiential learning—to see theory in practice. We want to go out into the community. We want the community to come to us.” Marlboro faculty members listened; we are finding ways to create opportunities for “engaged learning” based on faculty initiative, yet we have not found a model that students can count on semester after semester.

One thing you want to do at 65 is keep learning—isn’t that a hallmark of Marlboro? Recently I studied a number of reports on the job prospects for college students. Last year, nationwide, three-quarters of college graduates had found employment within a year of completing their degrees. Yet the wage differential is still significant: college graduates will earn significantly more than those with high school degrees. In 2011, as the recession dragged on, 4.1 percent of college graduates were unemployed, while more than double that number of high school graduates did not have jobs. As the economy generates more jobs into 2018, some 63 percent of them will require college studies, often a degree or more.

Why is “engaged learning” so important? One recent survey reports that 40 percent of college graduates found their first jobs as a result of internships they held while studying. That was one reason why we restored career services on campus in 2009, offering advice and career workshops along with a large array of internships and job listings. Student interns get to apply what they are learning and learn more about what animates them; they find mentors and expand their capabilities. The skills and confidence they gain lead to employment, to income, to making dreams possible—whether it is graduate school, a nonprofit career or starting their own enterprise. As one alumna said, “Marlboro grads don’t just take jobs, we create jobs.”

Day to day at the college, I’m very moved and affected by the transition in the faculty that we’re continuing to see at quite a rapid pace. Revered, honored, long-serving faculty are retiring each year, and that makes us sad. Yet there is also excitement that comes when someone new arrives, embraces the place and says, “I found my home.” A profound question for us, as it is for anyone who grows older, is how do you honor the past even while being open to new ideas? We must respect and build on the work of those who upheld this institution for years, making it what it is today. At the same time, when we invite new faculty here, we are saying, “Come to Marlboro and give us all your gifts.”

Marlboro is a fundamentally creative place. Although I’ve worked for years in the arts, I’ve never experienced an atmosphere where so much creativity occurs so abundantly that we don’t even name it. Creativity thrives by allowing the “widest and freest ranging of the human mind” according to Brewster Ghiselin in his 1952 book, The Creative Process . But to complete this process, “what is needed is control and direction.” The creative process is stimulated when previously disparate elements are related, similar to what happens here in interdisciplinary studies and team teaching.

I believe that creativity is a part of the fabric of Marlboro, starting with the veterans who came and slept under the apple trees while they made an old farmhouse into a dorm. It’s a habit of mind and a habit of making that happens in the faculty-student interactions and is also encouraged outside the classroom, studio and laboratory. It is also inspired by our being in a beautiful place. You gain a sense of both sanctuary and possibility here—a haven for learning, a haven for becoming. It gives me great hope that Marlboro has the creativity to evolve and renew itself to meet the needs of future students.

At 65 years old you step back—you assess. You say, “What do I want to do next? I don’t want to just repeat myself.” Similarly, I think institutions have to be very conscious of where they are headed. I want new stories for myself, and I feel the same way about Marlboro. We’ve got a great story, one that needs to be continually renewed and told.

Teachable Moments

To mark this 65th anniversary of the college, we checked under the hood of Marlboro’s legacy in the world of education—its pedagogical footprint so to speak. Here is what a few alumni, who themselves became teachers, have to say about how they learned what they learned at Marlboro, and how those lessons inform their teaching methods today.

Dan Hudkins ’73 is the director of instructional technology and information technology service and support at the Harker School in San Jose, California, where he also teaches moral philosophy and coaches softball. “Education was certainly on my radar when I got to Marlboro, and I took a Philosophy of Education class from Geri Pittman during my freshman year, but I didn’t become an educator until 1994—21 years after I graduated.

Dan Hudkins ’73 is the director of instructional technology and information technology service and support at the Harker School in San Jose, California, where he also teaches moral philosophy and coaches softball. “Education was certainly on my radar when I got to Marlboro, and I took a Philosophy of Education class from Geri Pittman during my freshman year, but I didn’t become an educator until 1994—21 years after I graduated.

“The pedagogy used at Marlboro influenced my own teaching style enormously. Respect for the learner, high expectations and a willingness to follow where the student’s interests lead were all things I learned from people like Geri Pittman, Roland Boyden and Dick Judd. My favorite learning moment was writing a concluding paper for a Marxism and Existentialism class in the spring of 1970. John Woodland, Nan deVries, Pedie Parks and I spent an enormous amount of time upstairs in John’s room, all working at the same time, reading bits to each other, arguing and rewriting.

“My favorite thing about teaching is unquestionably the students. There are these moments in class when I know that a student’s prior assumptions are shattered around their ankles and they have to start trying to understand themselves and the world from another perspective.

“Marlboro prepared me best by making me a fearless thinker and giving me the sometimes naive assumption that I could learn almost anything. I always begin with the idea that if I don’t understand or can’t figure it out, I will if I keep working at it.”

Arleen Tuchman ’77 is a history professor at Vanderbilt University, where she has been teaching since 1986. “When I went to graduate school to study the history of science and medicine, my goal was to teach at a liberal arts college. I’m not sure I imagined myself at a place as small as Marlboro, but I definitely wanted a position at a school that cared about teaching students to think critically, to express themselves clearly and to write well.

“My experiences at Marlboro definitely shaped my understanding of the liberal arts and influenced the way I engage my students in the classroom. I enjoy seminars the most because I love to see students get excited about ideas. Although I am clearly more knowledgeable than my students, I see my role as more akin to a facilitator, encouraging students to engage with texts and develop their own well-grounded analysis of the content.

“I fondly remember doing an independent study with Bob Engel on endocrinology. We would sit outside on the grass and I would ‘teach’ Bob what I had learned while he posed questions. I loved the reversal of roles and the relaxed nature of the exchange. Dick Lewontin came to Marlboro to teach population biology, and I’ll never forget his attempt to enact the concept of random genetic drift: he pushed his stomach out, rearranged the buttons on his shirt so they were in disarray, lowered his glasses to the tip of his nose and proceeded to stagger around in front of the class.”

John Gilliom ’82 is a professor of political science at Ohio University, where he has been teaching for 21 years and associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “My Marlboro experience made me want to be both a college professor and an amateur farmer. During the school years, I worked with Dick Judd on the arts of history and writing. During the summers, I worked with Sue Judd as her garden assistant and rototiller pilot. I now teach by day and farm by night. My university colleagues all find it rather bizarre, but I like to think that anyone from Marlboro would understand just fine.

“It’s impossible to make the pedagogical magic of Marlboro work at a 30,000-student university with classes ranging from a tiny 25 up to a few hundred. But there are a few things that can be drawn upon. Informality. Accessibility. Plain speech. Faith in the need for individuals to find their own way. And, of course, to this day, I believe that clear writing is the foundation of a college education.

“On a clear, warm, April day in my freshman year at Marlboro, I opted to skip my American Political Thought class to join nearly every other student in an impromptu springfest. I was dozing in the sun when an improbable cloud blocked the warmth. I opened my eyes to look up at the bowtie, pipe, tweed jacket and bushy eyebrows of professor Judd, who said, ‘I just wanted to make sure that you were okay.’ Then he simply grunted and walked away. It was the last class that I ever skipped. Care matters.”

Jake Dalton ’92 is an assistant professor of Tibetan Buddhism at University of California, Berkeley, where he has been teaching for three years. “Marlboro allowed me to develop my interests in Buddhist studies in ways no other college would. Working so closely with Jet Thomas and Birje Patil, reading texts side by side in their offices, taught me how to really read, how to let go of my own narcissistic concerns, leap into the text and allow it to transform me.

“The Plan of Concentration gave me the freedom to explore and was fundamental to building my confidence so that I could succeed in graduate school. Already on day one of grad school, I was way ahead of many of my peers, as I knew how to conduct research and write in a sustained way.

“There are two approaches to education. The first involves the student disciplining him or herself to work hard, the second involves the student finding what she or he loves and playing in it. Of course the latter is the ideal, and Marlboro supports its students to follow this path, to discover what they love and explore it in their own way. In my own teaching, I try to offer my students the same kind of open support, allowing them to find their own ways yet being there to help whenever they need it. It can be risky, as some may not find their way, but Marlboro taught me it is worth it.”

Barbara Whitney ’97 is the director of theater at Pingree School in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. “In many ways, Marlboro ruined me for subsequent educational experiences. I continue to marvel at the institution’s ability to be flexible in response to myriad situations as well as securely committed to a particular identity. Marlboro showed me that it’s possible to have a community of curiosity-driven, passionate learners who are supported by a community of curiosity-driven, passionate leaders.

Barbara Whitney ’97 is the director of theater at Pingree School in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. “In many ways, Marlboro ruined me for subsequent educational experiences. I continue to marvel at the institution’s ability to be flexible in response to myriad situations as well as securely committed to a particular identity. Marlboro showed me that it’s possible to have a community of curiosity-driven, passionate learners who are supported by a community of curiosity-driven, passionate leaders.

“Marlboro teachers generally practiced a mindset of respecting students and recognizing that student and teacher were together on the same path—sometimes at different places, but the same path. What forged the bond was asking questions, arguing, practicing, reflecting and sharing insights and personal experiences.

“Real learning can feel unsafe. It knocks up against assumptions and clichés, stereotypes and laziness. As a teacher I have to keep asking more questions rather than delivering answers. I have to believe that the classroom exists in order to serve communication, connection and discovery. My students have to know that I care about them, that I see them and that I will do whatever I can to cultivate the relationship and the environment so they can feel safe to question and discover.

“I think about Marlboro almost every day, little flickers of memory as I weave through clumps of students in the hall, hearing bells and lockers and the incessant tide of adolescent chatter. I try to bring a little of it with me, little threads of Vermont grace.”

Nate Totushek ’07 just finished his second year as chemistry teacher at School One in Providence, Rhode Island. “It’s a small, arts-oriented high school with a nice, cozy student-faculty ratio. This allows us to explore some of the deeper questions, like ‘What is empty space made of?’ I spent a year as a fulltime teacher in New York City before coming here, and it’s interesting how I am now in a place where I can combine the barefoot expeditionalism of Marlboro’s approach with the slick, cold steel of urban factory schooling.

“Teaching keeps me sharp, learning stuff I should have learned in high school. It also gives me a place to practice my stand-up routine and magic tricks. But education is far from being my ‘profession’; this was a revelation that I came to while studying education at Marlboro. A school needs a positive, slightly anarchistic presence or kids are likely to enter adulthood with a chip either on the shoulder or in the brain. Not sure which is worse, but at any rate schools are where society is designed, so I appreciate the Marlboro approach: It’s your education, take it or leave it.

“One thing that was extremely motivating at Marlboro was the feeling that nobody else was going to care whether I completed a project. This gave me a tremendous sense of ownership over my successes, because I had nobody else to blame for my failures. Perhaps it’s not the fastest way to skin a cat, but in many ways it’s the most thorough.”

65 years later...

Then

Then

- Number of students: 50

- Number of veterans: 35

- Percent women: 0

- Tuition, room and board: $1,200

- Fulltime faculty: 5

- Percent faculty of color: 0

- Areas of study: social studies, science, mathematics and languages

- Staff: 0

- Student accommodations: blacksmith shop and tents

- Renovations: Mather and dining hall

- New construction: sugarhouse

- Fashion statement: flannel shirts

- Footwear: saddle shoes and penny loafers

- Emblematic dead tree: removed from in front of dining hall

- Books in library: 12,000

- First graduating class: 1

- First commencement speaker: author Dorothy Canfield Fisher

- Poem read at commencement by: Robert Frost

- First fundraiser: $3,800 from a benefit concert by Rudolf Serkin and Adolf Busch

- Endowment: $0

- Marlboro Citizen ad: “Will exchange furnished room in rural Vermont for Florida lodging.”

- “We are interested in broad general education, cutting across the narrow lines of specialized interest.” —Walter Hendricks, president

- “Marlboro’s first aim is to develop citizens who will be effective in the task of making American democracy succeed.” —Marlboro College prospectus

Now

Now

- Number of students: 260

- Number of veterans: 2

- Percent women: 49

- Tuition, room and board: $46,000

- Fulltime faculty: 40

- Percent faculty of color: 10

- Areas of study: 34

- Staff: 67

- Student accommodations: 11 dorms plus cottages

- Renovations: admissions building

- New construction: greenhouse

- Fashion statement: flannel shirts

- Footwear: Sorels and bare feet

- Emblematic dead tree: removed from behind admissions building

- Books in library: 75,000

- Graduating class: 70

- Commencement speaker: author and environmentalist Bill McKibben

- Poem read at commencement by: Verandah Porche

- Recent fundraiser: $1,275,946 for 2011 Annual Fund

- Endowment: $36 million

- Marlboro Citizen ad: “I’m looking for a new best friend. Candidates should be Jewish, neurotic Freudians and pathological narcissists.”

- “We want to provide access to a broad range of knowledge that contains the seeds of its own expansion.” —Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president

- “The college promotes independence by requiring students to participate in the planning of their own programs of study and to act responsibly within a self-governing community.” —Marlboro College mission statement

Laura Stevenson turns a new page

“The first winter I was here we got a big snowstorm, and when I finally got to campus with my snowshoes and shovel, there were the president and the dean shoveling the walks around Mather,” said Laura Stevenson. “I pitched in, thinking, ‘I love this place.’” The staff has grown considerably since 1986, when Laura began teaching writing and literature at Marlboro, but her steadfast support for excellent writing at Marlboro has remained the same. This year we bid farewell to Laura, as she retires to the idyllic life of reading, writing and gardening at her Wilmington farm.

“Laura has been the best kind of colleague anybody could wish for,” said writing professor John Sheehy, who has worked alongside her since 1998. “She treated me, as a fellow teacher and scholar, the way she treated students: she wanted, always, to see our best. It is that quality in her—high expectations, combined with an unflagging confidence that we would meet them—that make her such a valuable ally for a writer, or for a teacher.”

Laura’s students over the years had the same assessment. “My favorite thing about having her as a professor was that she didn’t treat me as if she were a professor and I a student,” said Emily Field ’11. “She treated me as a peer and an equal, a respected fellow writer who could be negotiated with instead of a student who had to be dictated to. That kind of display of confidence does wonders for a writing student.”

Mark Roessler ’90 said, “I had an epic, young adult fantasy novel I’d been pecking away at through high school, and I was looking for guidance. Little did I know, Laura had been working on a young adult fantasy novel of her own. Over a weekend, she read my book. She told me she thought she could help me, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I was being taken seriously as a writer. Right off the bat, she began to prescribe remedies that have had a positive, lifelong effect.” Mark is now managing editor of the Valley Advocate.

Mark Roessler ’90 said, “I had an epic, young adult fantasy novel I’d been pecking away at through high school, and I was looking for guidance. Little did I know, Laura had been working on a young adult fantasy novel of her own. Over a weekend, she read my book. She told me she thought she could help me, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I was being taken seriously as a writer. Right off the bat, she began to prescribe remedies that have had a positive, lifelong effect.” Mark is now managing editor of the Valley Advocate.

“Laura does not condescend,” said Becca Mallary ’11, who found in her a perfect mentor for her Plan work in young adult fiction and feminism. “Her willingness to treat everyone as her equal is also what makes her such a masterful storyteller, and she taught me that talking down to your reader gets you nowhere. You must trust them if they’re going to trust you. The same can be said for the relationship between Plan sponsor and student, and it was such a joy to build a relationship based on trust, respect and mutual interests with her.”

“The most gratifying thing about teaching writing is watching the students get better,” said Laura. “They find they can do it, and then they just take off.”

Laura’s own writing took off as well, after she started teaching at Marlboro. A Yale-trained historian and author of Praise and Paradox: Merchants and Craftsmen in Elizabethan Popular Literature (1984), she has published four children’s novels since 1990 (Happily After All, The Island and the Ring, All the King’s Horses and A Castle in the Window) and in 2010 a novel for adults (Return in Kind) . A National Endowment for the Humanities research fellowship in 1996–97 resulted in several critical studies of late 19th-century children’s literature. But some of her greatest joys were found collaborating on short works of children’s fiction with Marlboro student illustrators.

“Through working with Laura I definitely became a better translator of thoughts into doodles— a crucial skill when illustrating,” said Ulla Valk ’03, who as a junior illustrated Laura’s “The Knight of the Side-Hill Wumpus” (Potash Hill , Summer-Fall 2002). “It was the first time I had to come up with characters and surroundings that actually corresponded with those in another person’s head. The particularly cool thing about doing that with Laura was that she has an awesomely rich imagination and this incredible ability to very elaborately describe what she envisions.”

Besides helping many individual student writers along, Laura’s lasting legacy at Marlboro has been her role in building a solid writing program. She said, “The writing requirement was in place when I came, but nobody quite knew how it worked or how long students got to pass it, and the whole thing was without direction. In the early 1990s the present setup of nonrequired, interdisciplinary writing seminars was created by the English Committee, under my direction, and that has stayed in place ever since. Writing isn’t taken for granted at Marlboro; it gets a lot of attention. That’s a real achievement—and certainly not just my achievement.”

Besides helping many individual student writers along, Laura’s lasting legacy at Marlboro has been her role in building a solid writing program. She said, “The writing requirement was in place when I came, but nobody quite knew how it worked or how long students got to pass it, and the whole thing was without direction. In the early 1990s the present setup of nonrequired, interdisciplinary writing seminars was created by the English Committee, under my direction, and that has stayed in place ever since. Writing isn’t taken for granted at Marlboro; it gets a lot of attention. That’s a real achievement—and certainly not just my achievement.”

Laura’s quiet confidence and patient persistence were an inspiration to many, made even more inspiring because she taught with what, for most teachers, would be a profound disability. She began losing her hearing before she came to Marlboro and taught for many years unable to hear at all before she had a cochlear implant.

“She soldiered on, always,” said John. “She figured out ways to teach when she couldn’t hear—to lead discussions, to confer privately with students, to guide students in their thinking and their writing. I think it is a testament to just what kind of teacher she is, what kind of person she is, that if you asked just about any of the students who loved her over the years to tell you about Laura, probably none of them would even mention that she is deaf. She made managing her deafness look easy.”

“Laura believes that everyone, everyone , has the ability to write well, and of course she is right,” said Emily. “I don’t know where she gets the compassion and the patience—or the wisdom. She doesn’t even make a big deal out of it, like she’s ‘rescuing’ a student. It’s just everyday business for her, getting good work out of a diverse array of students. Like it’s the easiest thing in the world.”

John added, “She made most things look easy. She is one of the smartest, funniest, most thoughtful and least complacent people I know. She is the absolute original of herself.”

Students visit City of Dreadful Delight

During Spring Break, seven students and three faculty members traveled to Mexico City to explore local history, art and the development of Mexican society and culture from precolonial times to the present. The trip was an extension of a spring course called City of Dreadful Delight, Mexico City: From Tenochtitlan, Capital City of the Aztec Empire, to Post-Modern Megalopolis, taught by Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson and art professors Tim Segar and Cathy Osman.

During Spring Break, seven students and three faculty members traveled to Mexico City to explore local history, art and the development of Mexican society and culture from precolonial times to the present. The trip was an extension of a spring course called City of Dreadful Delight, Mexico City: From Tenochtitlan, Capital City of the Aztec Empire, to Post-Modern Megalopolis, taught by Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson and art professors Tim Segar and Cathy Osman.

“This course focused on Mexico City as a case study in which to read the evidence of the historical, political, social, economic and cultural life of the country,” said Rosario. The March trip, made possible with support from the Christian Johnson Endeavor Fund, included visits to the ancient city of Teotihuacán, the historic canal district of Xochimilco and the house of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

“Frida’s house was truly amazing,” said freshman Caitlin Hargrove. “Her work hurts, because it’s so truthful and beautiful and ugly at the same time, and it tears away at you in a way that is good and healthy. Frida really lived, she really felt all her emotions with her whole body, and I think a lot of people these days can learn from that.”

Sophomore Daniel Kalla said, “A highlight was our day trip to Cholula to see the pyramids that were buried as protection from the Spaniards during the conquest, and visiting the cathedral built on the peak of the Great Pyramid.”

A two-day side trip brought the group to Puebla for a taste of colonial architecture, such as the 17th-century church Santa María Tonantsintla and other historic buildings. They also dropped in on alumna Jennifer Musi ’04, a former student of Cathy and Tim’s, who lives in a beautiful neighborhood of Mexico City, where she continues to pursue her interests in ceramics.

The students’ explorations of Mexico City brought to life what they had learned in class and helped inform discussions for the rest of the semester. “After studying the history of Mexico, the syncretism between the European influences and the indigenous influences is really apparent,” said junior Nicole Haeger.

“I learned more about gender roles in Mexico through just being there and observing,” added Caitlin, who is interested in women’s studies, gender and sexuality. “By watching the people and their relations with one another, you can learn a lot about the way that culture shapes thought processes.”

Sophomore James Munoz said, “ I enjoyed being fulfilled intellectually, culturally and emotionally.” Other Spring Break trips that played a similar role took students to Virginia to build houses for Habitats for Humanity and to the Navajo Nation in Arizona as part of an interdisciplinary class on service-learning with the Diné and Lakota peoples.

Marlboro hosts student symposium

Each spring the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences (VAAS) sponsors the Vermont Intercollegiate Student Symposium, at which students from across the state present work in diverse areas of study. This year Marlboro College hosted the symposium for the first time, welcoming more than 40 student presenters and other visitors from six colleges across the state on April 14.

“The conference was a wonderful opportunity for students from different institutions to share their interests with each other and a wider audience,” said Kate Ratcliff, Marlboro professor of American studies and this year’s symposium orchestrator. “It was so gratifying to see classrooms across campus filled with students from colleges all over Vermont.” Kate is on the board of VAAS, which was organized in 1965 to foster wider and more intensive participation in the arts, humanities and sciences in Vermont.

In addition to 15 students from Marlboro, participants came from the University of Vermont, St. Michaels College, Norwich University, Castleton State College and Green Mountain College. The presentations, which were organized in panels of four students and took place all across campus, drew from the fields of history, literature, political science, math, psychology, dance, theater and visual arts.

“I tried to create panels that linked papers around a broad common theme or themes and that included participants from different institutions, in the hopes of fostering interdisciplinary and intercollegiate dialogue,” said Kate.

A literary studies panel moderated by writing professor John Sheehy included senior Brandon Willits’ analysis of wilderness themes in William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. “I was fascinated with the idea of wilderness as a transformative space, and when I initially approached Faulkner I definitely believed that wilderness was spiritual,” said Brandon. But, like Isaac McCaslin in Faulkner’s seminal collection of stories, Brandon developed a different perception of wilderness while working for the park service last summer. “It was really important to me to understand how Faulkner uses language to present wilderness as a transformative space and to reconcile that with my own ideas of physically living in a wild space.”

In the same panel, junior Sam Grayck talked about the trials of translating Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince from the French. Other Marlboro students who presented at the symposium included senior Alex Tolstoi, who discussed Charles Phelps and the politics of internal dissent in revolutionary Vermont, and junior Alexia Boggs, who talked about Plato and the occupy movement. In a panel called “Men, Women and Family in American Culture,” moderated by Kate, sophomore Emma Thacker discussed complex families and senior Jory Shareef addressed historic representations of women.

Marlboro was well represented in the panel on visual and performing art, with entries from seniors Logan Smith (theater), Zach Parks (sculpture), Katherine Trahan (theater) and Cookie Harrist (dance). A panel titled “Constructions of Self and Other” included junior Cameron Cobane’s study of German director Fatih Akin, sophomore Aiden Keeva’s analysis of poet Gary Snyder’s ethics of eating and freshman Haley Peter’s insightful look at the legend of Bigfoot.

“Bigfoot gave America a strengthened sense of identity during the paranoia of the Cold War, and he represented a hope that transcended the newly understood destruction of the wilderness,” said Haley.

Senior Willie Finkel presented “The War Within: Famine and the Confederacy,” and senior Lauren Dushay talked about mentoring in the LGBTQ community. Kate said, “Several of the Marlboro seniors who participated told me it was a wonderful opportunity to articulate and discuss their research in preparation for upcoming orals.” It was a great experience for everyone involved, although one student noted that a disadvantage to participating was missing out on the other panels. Hopes were high that it would not be another 47 years before Marlboro hosts the spring symposium again.

New Marlboro offerings expand audience

This summer, a select group of teenagers are experiencing the intellectually challenging academic environment and rewards of a college course, more specifically a college course at Marlboro. Two weeklong seminars, led by philosophy professor William Edelglass and politics professor Meg Mott, are the first in a series of pre-college summer programs designed to give local youth the opportunity to study directly with faculty members and a group of other students passionate about learning.

“What does it mean to grow your food in a world where most of what we eat is produced by machines?” asks Meg, whose course this summer is called Eating Against the Machine. Students in her course will explore the connections between economics, politics and food, splitting their time between hands-on visits to farms and big-picture conversations. William’s course, Philosophies of the Wilderness, will give students the opportunity to reflect together on their relationship to “wilderness” and the moral dimensions of living with animals and ecosystems, as well as with other humans.

“These programs are great preparation for college, priming young minds and souls for life in an academic community and beyond,” said Ariel Brooks, director of non-degree programs. They complement other Marlboro programs designed to open doors for local teens, such as free classes for area high school students and Friday Night (rainbow) Lights, a drop-in group for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQQ) teens held at the Marlboro College Graduate School.

At the other end of the undergraduate years, Marlboro has made a concerted effort to make the graduate school more accessible and relevant to students on Potash Hill. The dual degree program allows students to build on their academic interests and earn a marketable graduate degree within a year or two of college graduation. In most cases, students can take graduate classes while still undergraduates, enabling them to start their graduate program ahead of the game and reduce their credit fees.

“Marlboro College’s dual degree program is the best of both worlds,” said Ariel. “Students in the program can continue their Marlboro studies on their own terms, knowing that the graduate school will allow them to apply their academic experience to a career in education, business or nonprofit management.”

Graduate programs offered through the dual degree program are the Master of Arts in Teaching for Social Justice, the Master of Arts in Teaching with Technology, the Master of Science in Managing Mission-Driven Organizations and the MBA in Managing for Sustainability. Marlboro students will find many familiar features at the graduate school, including small classes, self-directed learning, project-based work and a focus on clear communication.

“I wanted the same level of creative and critical thinking in a teacher certification program that characterized my undergraduate experience,” said Amanda DeBisschop ’10, who is enrolled in the teaching for social justice program. “The faculty is completely dedicated to educating active and effective teachers, and the students are determined to learn what good teaching looks and feels like.”

And more

This year marked a bumper crop of faculty babies, including Lars Marion Lyndgaard (left), born to writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard and his wife, Marian, on February 15, and Henry Brett Hobbie (right), born to biology professor Jaime Tanner and her husband, Than, on December 19. Not pictured are Molly Rose Ollis, born on August 7 (to math professor Matt Ollis and his wife, Gemma); Elana Oralee Wickenden, born on September 14 (to history professor Adam Franklin-Lyon and his wife, Maggie); and Raziq Lyle Latif, born on October 18 (to religion professor Amer Latif and his wife, Ruby). Must be something in the food.

This year marked a bumper crop of faculty babies, including Lars Marion Lyndgaard (left), born to writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard and his wife, Marian, on February 15, and Henry Brett Hobbie (right), born to biology professor Jaime Tanner and her husband, Than, on December 19. Not pictured are Molly Rose Ollis, born on August 7 (to math professor Matt Ollis and his wife, Gemma); Elana Oralee Wickenden, born on September 14 (to history professor Adam Franklin-Lyon and his wife, Maggie); and Raziq Lyle Latif, born on October 18 (to religion professor Amer Latif and his wife, Ruby). Must be something in the food.