On & Off the Hill

This issue celebrates Marlboro's 65 years, including a look at how the college has changed and what some teachers learned about learning while they were here. We also say farewell to writing professor Laura Stevenson, join some students on their trip to Mexico City and see what went down at the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium this year.

This issue celebrates Marlboro's 65 years, including a look at how the college has changed and what some teachers learned about learning while they were here. We also say farewell to writing professor Laura Stevenson, join some students on their trip to Mexico City and see what went down at the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences Intercollegiate Student Symposium this year.

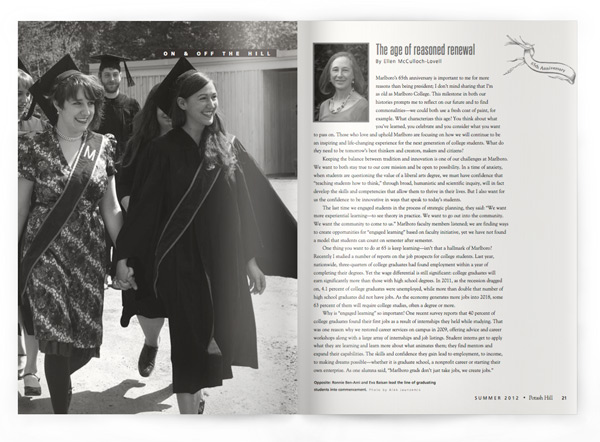

The age of reasoned renewal

By Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

Marlboro’s 65th anniversary is important to me for more reasons than being president; I don’t mind sharing that I’m as old as Marlboro College. This milestone in both our histories prompts me to reflect on our future and to find commonalities—we could both use a fresh coat of paint, for example. What characterizes this age? You think about what you’ve learned, you celebrate and you consider what you want to pass on. Those who love and uphold Marlboro are focusing on how we will continue to be an inspiring and life-changing experience for the next generation of college students. What do they need to be tomorrow’s best thinkers and creators, makers and citizens?

Marlboro’s 65th anniversary is important to me for more reasons than being president; I don’t mind sharing that I’m as old as Marlboro College. This milestone in both our histories prompts me to reflect on our future and to find commonalities—we could both use a fresh coat of paint, for example. What characterizes this age? You think about what you’ve learned, you celebrate and you consider what you want to pass on. Those who love and uphold Marlboro are focusing on how we will continue to be an inspiring and life-changing experience for the next generation of college students. What do they need to be tomorrow’s best thinkers and creators, makers and citizens?

Keeping the balance between tradition and innovation is one of our challenges at Marlboro. We want to both stay true to our core mission and be open to possibility. In a time of anxiety, when students are questioning the value of a liberal arts degree, we must have confidence that “teaching students how to think,” through broad, humanistic and scientific inquiry, will in fact develop the skills and competencies that allow them to thrive in their lives. But I also want for us the confidence to be innovative in ways that speak to today’s students.

The last time we engaged students in the process of strategic planning, they said: “We want more experiential learning—to see theory in practice. We want to go out into the community. We want the community to come to us.” Marlboro faculty members listened; we are finding ways to create opportunities for “engaged learning” based on faculty initiative, yet we have not found a model that students can count on semester after semester.

One thing you want to do at 65 is keep learning—isn’t that a hallmark of Marlboro? Recently I studied a number of reports on the job prospects for college students. Last year, nationwide, three-quarters of college graduates had found employment within a year of completing their degrees. Yet the wage differential is still significant: college graduates will earn significantly more than those with high school degrees. In 2011, as the recession dragged on, 4.1 percent of college graduates were unemployed, while more than double that number of high school graduates did not have jobs. As the economy generates more jobs into 2018, some 63 percent of them will require college studies, often a degree or more.

Why is “engaged learning” so important? One recent survey reports that 40 percent of college graduates found their first jobs as a result of internships they held while studying. That was one reason why we restored career services on campus in 2009, offering advice and career workshops along with a large array of internships and job listings. Student interns get to apply what they are learning and learn more about what animates them; they find mentors and expand their capabilities. The skills and confidence they gain lead to employment, to income, to making dreams possible—whether it is graduate school, a nonprofit career or starting their own enterprise. As one alumna said, “Marlboro grads don’t just take jobs, we create jobs.”

Day to day at the college, I’m very moved and affected by the transition in the faculty that we’re continuing to see at quite a rapid pace. Revered, honored, long-serving faculty are retiring each year, and that makes us sad. Yet there is also excitement that comes when someone new arrives, embraces the place and says, “I found my home.” A profound question for us, as it is for anyone who grows older, is how do you honor the past even while being open to new ideas? We must respect and build on the work of those who upheld this institution for years, making it what it is today. At the same time, when we invite new faculty here, we are saying, “Come to Marlboro and give us all your gifts.”

Marlboro is a fundamentally creative place. Although I’ve worked for years in the arts, I’ve never experienced an atmosphere where so much creativity occurs so abundantly that we don’t even name it. Creativity thrives by allowing the “widest and freest ranging of the human mind” according to Brewster Ghiselin in his 1952 book, The Creative Process . But to complete this process, “what is needed is control and direction.” The creative process is stimulated when previously disparate elements are related, similar to what happens here in interdisciplinary studies and team teaching.

I believe that creativity is a part of the fabric of Marlboro, starting with the veterans who came and slept under the apple trees while they made an old farmhouse into a dorm. It’s a habit of mind and a habit of making that happens in the faculty-student interactions and is also encouraged outside the classroom, studio and laboratory. It is also inspired by our being in a beautiful place. You gain a sense of both sanctuary and possibility here—a haven for learning, a haven for becoming. It gives me great hope that Marlboro has the creativity to evolve and renew itself to meet the needs of future students.

At 65 years old you step back—you assess. You say, “What do I want to do next? I don’t want to just repeat myself.” Similarly, I think institutions have to be very conscious of where they are headed. I want new stories for myself, and I feel the same way about Marlboro. We’ve got a great story, one that needs to be continually renewed and told.

Teachable Moments

To mark this 65th anniversary of the college, we checked under the hood of Marlboro’s legacy in the world of education—its pedagogical footprint so to speak. Here is what a few alumni, who themselves became teachers, have to say about how they learned what they learned at Marlboro, and how those lessons inform their teaching methods today.

Dan Hudkins ’73 is the director of instructional technology and information technology service and support at the Harker School in San Jose, California, where he also teaches moral philosophy and coaches softball. “Education was certainly on my radar when I got to Marlboro, and I took a Philosophy of Education class from Geri Pittman during my freshman year, but I didn’t become an educator until 1994—21 years after I graduated.

Dan Hudkins ’73 is the director of instructional technology and information technology service and support at the Harker School in San Jose, California, where he also teaches moral philosophy and coaches softball. “Education was certainly on my radar when I got to Marlboro, and I took a Philosophy of Education class from Geri Pittman during my freshman year, but I didn’t become an educator until 1994—21 years after I graduated.

“The pedagogy used at Marlboro influenced my own teaching style enormously. Respect for the learner, high expectations and a willingness to follow where the student’s interests lead were all things I learned from people like Geri Pittman, Roland Boyden and Dick Judd. My favorite learning moment was writing a concluding paper for a Marxism and Existentialism class in the spring of 1970. John Woodland, Nan deVries, Pedie Parks and I spent an enormous amount of time upstairs in John’s room, all working at the same time, reading bits to each other, arguing and rewriting.

“My favorite thing about teaching is unquestionably the students. There are these moments in class when I know that a student’s prior assumptions are shattered around their ankles and they have to start trying to understand themselves and the world from another perspective.

“Marlboro prepared me best by making me a fearless thinker and giving me the sometimes naive assumption that I could learn almost anything. I always begin with the idea that if I don’t understand or can’t figure it out, I will if I keep working at it.”

Arleen Tuchman ’77 is a history professor at Vanderbilt University, where she has been teaching since 1986. “When I went to graduate school to study the history of science and medicine, my goal was to teach at a liberal arts college. I’m not sure I imagined myself at a place as small as Marlboro, but I definitely wanted a position at a school that cared about teaching students to think critically, to express themselves clearly and to write well.

“My experiences at Marlboro definitely shaped my understanding of the liberal arts and influenced the way I engage my students in the classroom. I enjoy seminars the most because I love to see students get excited about ideas. Although I am clearly more knowledgeable than my students, I see my role as more akin to a facilitator, encouraging students to engage with texts and develop their own well-grounded analysis of the content.

“I fondly remember doing an independent study with Bob Engel on endocrinology. We would sit outside on the grass and I would ‘teach’ Bob what I had learned while he posed questions. I loved the reversal of roles and the relaxed nature of the exchange. Dick Lewontin came to Marlboro to teach population biology, and I’ll never forget his attempt to enact the concept of random genetic drift: he pushed his stomach out, rearranged the buttons on his shirt so they were in disarray, lowered his glasses to the tip of his nose and proceeded to stagger around in front of the class.”

John Gilliom ’82 is a professor of political science at Ohio University, where he has been teaching for 21 years and associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “My Marlboro experience made me want to be both a college professor and an amateur farmer. During the school years, I worked with Dick Judd on the arts of history and writing. During the summers, I worked with Sue Judd as her garden assistant and rototiller pilot. I now teach by day and farm by night. My university colleagues all find it rather bizarre, but I like to think that anyone from Marlboro would understand just fine.

“It’s impossible to make the pedagogical magic of Marlboro work at a 30,000-student university with classes ranging from a tiny 25 up to a few hundred. But there are a few things that can be drawn upon. Informality. Accessibility. Plain speech. Faith in the need for individuals to find their own way. And, of course, to this day, I believe that clear writing is the foundation of a college education.

“On a clear, warm, April day in my freshman year at Marlboro, I opted to skip my American Political Thought class to join nearly every other student in an impromptu springfest. I was dozing in the sun when an improbable cloud blocked the warmth. I opened my eyes to look up at the bowtie, pipe, tweed jacket and bushy eyebrows of professor Judd, who said, ‘I just wanted to make sure that you were okay.’ Then he simply grunted and walked away. It was the last class that I ever skipped. Care matters.”

Jake Dalton ’92 is an assistant professor of Tibetan Buddhism at University of California, Berkeley, where he has been teaching for three years. “Marlboro allowed me to develop my interests in Buddhist studies in ways no other college would. Working so closely with Jet Thomas and Birje Patil, reading texts side by side in their offices, taught me how to really read, how to let go of my own narcissistic concerns, leap into the text and allow it to transform me.

“The Plan of Concentration gave me the freedom to explore and was fundamental to building my confidence so that I could succeed in graduate school. Already on day one of grad school, I was way ahead of many of my peers, as I knew how to conduct research and write in a sustained way.

“There are two approaches to education. The first involves the student disciplining him or herself to work hard, the second involves the student finding what she or he loves and playing in it. Of course the latter is the ideal, and Marlboro supports its students to follow this path, to discover what they love and explore it in their own way. In my own teaching, I try to offer my students the same kind of open support, allowing them to find their own ways yet being there to help whenever they need it. It can be risky, as some may not find their way, but Marlboro taught me it is worth it.”

Barbara Whitney ’97 is the director of theater at Pingree School in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. “In many ways, Marlboro ruined me for subsequent educational experiences. I continue to marvel at the institution’s ability to be flexible in response to myriad situations as well as securely committed to a particular identity. Marlboro showed me that it’s possible to have a community of curiosity-driven, passionate learners who are supported by a community of curiosity-driven, passionate leaders.

Barbara Whitney ’97 is the director of theater at Pingree School in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. “In many ways, Marlboro ruined me for subsequent educational experiences. I continue to marvel at the institution’s ability to be flexible in response to myriad situations as well as securely committed to a particular identity. Marlboro showed me that it’s possible to have a community of curiosity-driven, passionate learners who are supported by a community of curiosity-driven, passionate leaders.

“Marlboro teachers generally practiced a mindset of respecting students and recognizing that student and teacher were together on the same path—sometimes at different places, but the same path. What forged the bond was asking questions, arguing, practicing, reflecting and sharing insights and personal experiences.

“Real learning can feel unsafe. It knocks up against assumptions and clichés, stereotypes and laziness. As a teacher I have to keep asking more questions rather than delivering answers. I have to believe that the classroom exists in order to serve communication, connection and discovery. My students have to know that I care about them, that I see them and that I will do whatever I can to cultivate the relationship and the environment so they can feel safe to question and discover.

“I think about Marlboro almost every day, little flickers of memory as I weave through clumps of students in the hall, hearing bells and lockers and the incessant tide of adolescent chatter. I try to bring a little of it with me, little threads of Vermont grace.”

Nate Totushek ’07 just finished his second year as chemistry teacher at School One in Providence, Rhode Island. “It’s a small, arts-oriented high school with a nice, cozy student-faculty ratio. This allows us to explore some of the deeper questions, like ‘What is empty space made of?’ I spent a year as a fulltime teacher in New York City before coming here, and it’s interesting how I am now in a place where I can combine the barefoot expeditionalism of Marlboro’s approach with the slick, cold steel of urban factory schooling.

“Teaching keeps me sharp, learning stuff I should have learned in high school. It also gives me a place to practice my stand-up routine and magic tricks. But education is far from being my ‘profession’; this was a revelation that I came to while studying education at Marlboro. A school needs a positive, slightly anarchistic presence or kids are likely to enter adulthood with a chip either on the shoulder or in the brain. Not sure which is worse, but at any rate schools are where society is designed, so I appreciate the Marlboro approach: It’s your education, take it or leave it.

“One thing that was extremely motivating at Marlboro was the feeling that nobody else was going to care whether I completed a project. This gave me a tremendous sense of ownership over my successes, because I had nobody else to blame for my failures. Perhaps it’s not the fastest way to skin a cat, but in many ways it’s the most thorough.”

65 years later...

Then

Then

- Number of students: 50

- Number of veterans: 35

- Percent women: 0

- Tuition, room and board: $1,200

- Fulltime faculty: 5

- Percent faculty of color: 0

- Areas of study: social studies, science, mathematics and languages

- Staff: 0

- Student accommodations: blacksmith shop and tents

- Renovations: Mather and dining hall

- New construction: sugarhouse

- Fashion statement: flannel shirts

- Footwear: saddle shoes and penny loafers

- Emblematic dead tree: removed from in front of dining hall

- Books in library: 12,000

- First graduating class: 1

- First commencement speaker: author Dorothy Canfield Fisher

- Poem read at commencement by: Robert Frost

- First fundraiser: $3,800 from a benefit concert by Rudolf Serkin and Adolf Busch

- Endowment: $0

- Marlboro Citizen ad: “Will exchange furnished room in rural Vermont for Florida lodging.”

- “We are interested in broad general education, cutting across the narrow lines of specialized interest.” —Walter Hendricks, president

- “Marlboro’s first aim is to develop citizens who will be effective in the task of making American democracy succeed.” —Marlboro College prospectus

Now

Now

- Number of students: 260

- Number of veterans: 2

- Percent women: 49

- Tuition, room and board: $46,000

- Fulltime faculty: 40

- Percent faculty of color: 10

- Areas of study: 34

- Staff: 67

- Student accommodations: 11 dorms plus cottages

- Renovations: admissions building

- New construction: greenhouse

- Fashion statement: flannel shirts

- Footwear: Sorels and bare feet

- Emblematic dead tree: removed from behind admissions building

- Books in library: 75,000

- Graduating class: 70

- Commencement speaker: author and environmentalist Bill McKibben

- Poem read at commencement by: Verandah Porche

- Recent fundraiser: $1,275,946 for 2011 Annual Fund

- Endowment: $36 million

- Marlboro Citizen ad: “I’m looking for a new best friend. Candidates should be Jewish, neurotic Freudians and pathological narcissists.”

- “We want to provide access to a broad range of knowledge that contains the seeds of its own expansion.” —Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president

- “The college promotes independence by requiring students to participate in the planning of their own programs of study and to act responsibly within a self-governing community.” —Marlboro College mission statement

Laura Stevenson turns a new page

“The first winter I was here we got a big snowstorm, and when I finally got to campus with my snowshoes and shovel, there were the president and the dean shoveling the walks around Mather,” said Laura Stevenson. “I pitched in, thinking, ‘I love this place.’” The staff has grown considerably since 1986, when Laura began teaching writing and literature at Marlboro, but her steadfast support for excellent writing at Marlboro has remained the same. This year we bid farewell to Laura, as she retires to the idyllic life of reading, writing and gardening at her Wilmington farm.

“Laura has been the best kind of colleague anybody could wish for,” said writing professor John Sheehy, who has worked alongside her since 1998. “She treated me, as a fellow teacher and scholar, the way she treated students: she wanted, always, to see our best. It is that quality in her—high expectations, combined with an unflagging confidence that we would meet them—that make her such a valuable ally for a writer, or for a teacher.”

Laura’s students over the years had the same assessment. “My favorite thing about having her as a professor was that she didn’t treat me as if she were a professor and I a student,” said Emily Field ’11. “She treated me as a peer and an equal, a respected fellow writer who could be negotiated with instead of a student who had to be dictated to. That kind of display of confidence does wonders for a writing student.”

Mark Roessler ’90 said, “I had an epic, young adult fantasy novel I’d been pecking away at through high school, and I was looking for guidance. Little did I know, Laura had been working on a young adult fantasy novel of her own. Over a weekend, she read my book. She told me she thought she could help me, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I was being taken seriously as a writer. Right off the bat, she began to prescribe remedies that have had a positive, lifelong effect.” Mark is now managing editor of the Valley Advocate.

Mark Roessler ’90 said, “I had an epic, young adult fantasy novel I’d been pecking away at through high school, and I was looking for guidance. Little did I know, Laura had been working on a young adult fantasy novel of her own. Over a weekend, she read my book. She told me she thought she could help me, and for the first time in my life, I felt that I was being taken seriously as a writer. Right off the bat, she began to prescribe remedies that have had a positive, lifelong effect.” Mark is now managing editor of the Valley Advocate.

“Laura does not condescend,” said Becca Mallary ’11, who found in her a perfect mentor for her Plan work in young adult fiction and feminism. “Her willingness to treat everyone as her equal is also what makes her such a masterful storyteller, and she taught me that talking down to your reader gets you nowhere. You must trust them if they’re going to trust you. The same can be said for the relationship between Plan sponsor and student, and it was such a joy to build a relationship based on trust, respect and mutual interests with her.”

“The most gratifying thing about teaching writing is watching the students get better,” said Laura. “They find they can do it, and then they just take off.”

Laura’s own writing took off as well, after she started teaching at Marlboro. A Yale-trained historian and author of Praise and Paradox: Merchants and Craftsmen in Elizabethan Popular Literature (1984), she has published four children’s novels since 1990 (Happily After All, The Island and the Ring, All the King’s Horses and A Castle in the Window) and in 2010 a novel for adults (Return in Kind) . A National Endowment for the Humanities research fellowship in 1996–97 resulted in several critical studies of late 19th-century children’s literature. But some of her greatest joys were found collaborating on short works of children’s fiction with Marlboro student illustrators.

“Through working with Laura I definitely became a better translator of thoughts into doodles— a crucial skill when illustrating,” said Ulla Valk ’03, who as a junior illustrated Laura’s “The Knight of the Side-Hill Wumpus” (Potash Hill , Summer-Fall 2002). “It was the first time I had to come up with characters and surroundings that actually corresponded with those in another person’s head. The particularly cool thing about doing that with Laura was that she has an awesomely rich imagination and this incredible ability to very elaborately describe what she envisions.”

Besides helping many individual student writers along, Laura’s lasting legacy at Marlboro has been her role in building a solid writing program. She said, “The writing requirement was in place when I came, but nobody quite knew how it worked or how long students got to pass it, and the whole thing was without direction. In the early 1990s the present setup of nonrequired, interdisciplinary writing seminars was created by the English Committee, under my direction, and that has stayed in place ever since. Writing isn’t taken for granted at Marlboro; it gets a lot of attention. That’s a real achievement—and certainly not just my achievement.”

Besides helping many individual student writers along, Laura’s lasting legacy at Marlboro has been her role in building a solid writing program. She said, “The writing requirement was in place when I came, but nobody quite knew how it worked or how long students got to pass it, and the whole thing was without direction. In the early 1990s the present setup of nonrequired, interdisciplinary writing seminars was created by the English Committee, under my direction, and that has stayed in place ever since. Writing isn’t taken for granted at Marlboro; it gets a lot of attention. That’s a real achievement—and certainly not just my achievement.”

Laura’s quiet confidence and patient persistence were an inspiration to many, made even more inspiring because she taught with what, for most teachers, would be a profound disability. She began losing her hearing before she came to Marlboro and taught for many years unable to hear at all before she had a cochlear implant.

“She soldiered on, always,” said John. “She figured out ways to teach when she couldn’t hear—to lead discussions, to confer privately with students, to guide students in their thinking and their writing. I think it is a testament to just what kind of teacher she is, what kind of person she is, that if you asked just about any of the students who loved her over the years to tell you about Laura, probably none of them would even mention that she is deaf. She made managing her deafness look easy.”

“Laura believes that everyone, everyone , has the ability to write well, and of course she is right,” said Emily. “I don’t know where she gets the compassion and the patience—or the wisdom. She doesn’t even make a big deal out of it, like she’s ‘rescuing’ a student. It’s just everyday business for her, getting good work out of a diverse array of students. Like it’s the easiest thing in the world.”

John added, “She made most things look easy. She is one of the smartest, funniest, most thoughtful and least complacent people I know. She is the absolute original of herself.”

Students visit City of Dreadful Delight

During Spring Break, seven students and three faculty members traveled to Mexico City to explore local history, art and the development of Mexican society and culture from precolonial times to the present. The trip was an extension of a spring course called City of Dreadful Delight, Mexico City: From Tenochtitlan, Capital City of the Aztec Empire, to Post-Modern Megalopolis, taught by Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson and art professors Tim Segar and Cathy Osman.

During Spring Break, seven students and three faculty members traveled to Mexico City to explore local history, art and the development of Mexican society and culture from precolonial times to the present. The trip was an extension of a spring course called City of Dreadful Delight, Mexico City: From Tenochtitlan, Capital City of the Aztec Empire, to Post-Modern Megalopolis, taught by Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson and art professors Tim Segar and Cathy Osman.

“This course focused on Mexico City as a case study in which to read the evidence of the historical, political, social, economic and cultural life of the country,” said Rosario. The March trip, made possible with support from the Christian Johnson Endeavor Fund, included visits to the ancient city of Teotihuacán, the historic canal district of Xochimilco and the house of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

“Frida’s house was truly amazing,” said freshman Caitlin Hargrove. “Her work hurts, because it’s so truthful and beautiful and ugly at the same time, and it tears away at you in a way that is good and healthy. Frida really lived, she really felt all her emotions with her whole body, and I think a lot of people these days can learn from that.”

Sophomore Daniel Kalla said, “A highlight was our day trip to Cholula to see the pyramids that were buried as protection from the Spaniards during the conquest, and visiting the cathedral built on the peak of the Great Pyramid.”

A two-day side trip brought the group to Puebla for a taste of colonial architecture, such as the 17th-century church Santa María Tonantsintla and other historic buildings. They also dropped in on alumna Jennifer Musi ’04, a former student of Cathy and Tim’s, who lives in a beautiful neighborhood of Mexico City, where she continues to pursue her interests in ceramics.

The students’ explorations of Mexico City brought to life what they had learned in class and helped inform discussions for the rest of the semester. “After studying the history of Mexico, the syncretism between the European influences and the indigenous influences is really apparent,” said junior Nicole Haeger.

“I learned more about gender roles in Mexico through just being there and observing,” added Caitlin, who is interested in women’s studies, gender and sexuality. “By watching the people and their relations with one another, you can learn a lot about the way that culture shapes thought processes.”

Sophomore James Munoz said, “ I enjoyed being fulfilled intellectually, culturally and emotionally.” Other Spring Break trips that played a similar role took students to Virginia to build houses for Habitats for Humanity and to the Navajo Nation in Arizona as part of an interdisciplinary class on service-learning with the Diné and Lakota peoples.

Marlboro hosts student symposium

Each spring the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences (VAAS) sponsors the Vermont Intercollegiate Student Symposium, at which students from across the state present work in diverse areas of study. This year Marlboro College hosted the symposium for the first time, welcoming more than 40 student presenters and other visitors from six colleges across the state on April 14.

“The conference was a wonderful opportunity for students from different institutions to share their interests with each other and a wider audience,” said Kate Ratcliff, Marlboro professor of American studies and this year’s symposium orchestrator. “It was so gratifying to see classrooms across campus filled with students from colleges all over Vermont.” Kate is on the board of VAAS, which was organized in 1965 to foster wider and more intensive participation in the arts, humanities and sciences in Vermont.

In addition to 15 students from Marlboro, participants came from the University of Vermont, St. Michaels College, Norwich University, Castleton State College and Green Mountain College. The presentations, which were organized in panels of four students and took place all across campus, drew from the fields of history, literature, political science, math, psychology, dance, theater and visual arts.

“I tried to create panels that linked papers around a broad common theme or themes and that included participants from different institutions, in the hopes of fostering interdisciplinary and intercollegiate dialogue,” said Kate.

A literary studies panel moderated by writing professor John Sheehy included senior Brandon Willits’ analysis of wilderness themes in William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. “I was fascinated with the idea of wilderness as a transformative space, and when I initially approached Faulkner I definitely believed that wilderness was spiritual,” said Brandon. But, like Isaac McCaslin in Faulkner’s seminal collection of stories, Brandon developed a different perception of wilderness while working for the park service last summer. “It was really important to me to understand how Faulkner uses language to present wilderness as a transformative space and to reconcile that with my own ideas of physically living in a wild space.”

In the same panel, junior Sam Grayck talked about the trials of translating Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince from the French. Other Marlboro students who presented at the symposium included senior Alex Tolstoi, who discussed Charles Phelps and the politics of internal dissent in revolutionary Vermont, and junior Alexia Boggs, who talked about Plato and the occupy movement. In a panel called “Men, Women and Family in American Culture,” moderated by Kate, sophomore Emma Thacker discussed complex families and senior Jory Shareef addressed historic representations of women.

Marlboro was well represented in the panel on visual and performing art, with entries from seniors Logan Smith (theater), Zach Parks (sculpture), Katherine Trahan (theater) and Cookie Harrist (dance). A panel titled “Constructions of Self and Other” included junior Cameron Cobane’s study of German director Fatih Akin, sophomore Aiden Keeva’s analysis of poet Gary Snyder’s ethics of eating and freshman Haley Peter’s insightful look at the legend of Bigfoot.

“Bigfoot gave America a strengthened sense of identity during the paranoia of the Cold War, and he represented a hope that transcended the newly understood destruction of the wilderness,” said Haley.

Senior Willie Finkel presented “The War Within: Famine and the Confederacy,” and senior Lauren Dushay talked about mentoring in the LGBTQ community. Kate said, “Several of the Marlboro seniors who participated told me it was a wonderful opportunity to articulate and discuss their research in preparation for upcoming orals.” It was a great experience for everyone involved, although one student noted that a disadvantage to participating was missing out on the other panels. Hopes were high that it would not be another 47 years before Marlboro hosts the spring symposium again.

New Marlboro offerings expand audience

This summer, a select group of teenagers are experiencing the intellectually challenging academic environment and rewards of a college course, more specifically a college course at Marlboro. Two weeklong seminars, led by philosophy professor William Edelglass and politics professor Meg Mott, are the first in a series of pre-college summer programs designed to give local youth the opportunity to study directly with faculty members and a group of other students passionate about learning.

“What does it mean to grow your food in a world where most of what we eat is produced by machines?” asks Meg, whose course this summer is called Eating Against the Machine. Students in her course will explore the connections between economics, politics and food, splitting their time between hands-on visits to farms and big-picture conversations. William’s course, Philosophies of the Wilderness, will give students the opportunity to reflect together on their relationship to “wilderness” and the moral dimensions of living with animals and ecosystems, as well as with other humans.

“These programs are great preparation for college, priming young minds and souls for life in an academic community and beyond,” said Ariel Brooks, director of non-degree programs. They complement other Marlboro programs designed to open doors for local teens, such as free classes for area high school students and Friday Night (rainbow) Lights, a drop-in group for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQQ) teens held at the Marlboro College Graduate School.

At the other end of the undergraduate years, Marlboro has made a concerted effort to make the graduate school more accessible and relevant to students on Potash Hill. The dual degree program allows students to build on their academic interests and earn a marketable graduate degree within a year or two of college graduation. In most cases, students can take graduate classes while still undergraduates, enabling them to start their graduate program ahead of the game and reduce their credit fees.

“Marlboro College’s dual degree program is the best of both worlds,” said Ariel. “Students in the program can continue their Marlboro studies on their own terms, knowing that the graduate school will allow them to apply their academic experience to a career in education, business or nonprofit management.”

Graduate programs offered through the dual degree program are the Master of Arts in Teaching for Social Justice, the Master of Arts in Teaching with Technology, the Master of Science in Managing Mission-Driven Organizations and the MBA in Managing for Sustainability. Marlboro students will find many familiar features at the graduate school, including small classes, self-directed learning, project-based work and a focus on clear communication.

“I wanted the same level of creative and critical thinking in a teacher certification program that characterized my undergraduate experience,” said Amanda DeBisschop ’10, who is enrolled in the teaching for social justice program. “The faculty is completely dedicated to educating active and effective teachers, and the students are determined to learn what good teaching looks and feels like.”

And more

This year marked a bumper crop of faculty babies, including Lars Marion Lyndgaard (left), born to writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard and his wife, Marian, on February 15, and Henry Brett Hobbie (right), born to biology professor Jaime Tanner and her husband, Than, on December 19. Not pictured are Molly Rose Ollis, born on August 7 (to math professor Matt Ollis and his wife, Gemma); Elana Oralee Wickenden, born on September 14 (to history professor Adam Franklin-Lyon and his wife, Maggie); and Raziq Lyle Latif, born on October 18 (to religion professor Amer Latif and his wife, Ruby). Must be something in the food.

This year marked a bumper crop of faculty babies, including Lars Marion Lyndgaard (left), born to writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard and his wife, Marian, on February 15, and Henry Brett Hobbie (right), born to biology professor Jaime Tanner and her husband, Than, on December 19. Not pictured are Molly Rose Ollis, born on August 7 (to math professor Matt Ollis and his wife, Gemma); Elana Oralee Wickenden, born on September 14 (to history professor Adam Franklin-Lyon and his wife, Maggie); and Raziq Lyle Latif, born on October 18 (to religion professor Amer Latif and his wife, Ruby). Must be something in the food.

Where and when else can you do winter, spring and summer sports at the same time? In March, writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard, Willson Gaul ’10, health services director Max Foldeak, outdoor program director Randy Knaggs ’94 and his partner, Deb Dorsett, participated in the first annual Berkshire Highlands Pentathlon, an event benefitting local land preservation and education. Their team came in sixth (out of 56 teams) in the five events: a 10-kilometer trail run, 23 miles of road biking, five miles of kayaking, a mile climb to the top of a mountain and a downhill ski to the finish.

Where and when else can you do winter, spring and summer sports at the same time? In March, writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard, Willson Gaul ’10, health services director Max Foldeak, outdoor program director Randy Knaggs ’94 and his partner, Deb Dorsett, participated in the first annual Berkshire Highlands Pentathlon, an event benefitting local land preservation and education. Their team came in sixth (out of 56 teams) in the five events: a 10-kilometer trail run, 23 miles of road biking, five miles of kayaking, a mile climb to the top of a mountain and a downhill ski to the finish.

The library’s first-ever letter-writing social brought a flurry of clackity-clacking activity to the reading room in February. Students accustomed to texting on smart phones waxed nostalgic while typing on machines with names like Remington, Smith Corona and Olympia. The fresh baked goodies, tea and “soda pop” bottled in antique 7-ounce bottles rounded out the experience, sure to be repeated in future years.

The library’s first-ever letter-writing social brought a flurry of clackity-clacking activity to the reading room in February. Students accustomed to texting on smart phones waxed nostalgic while typing on machines with names like Remington, Smith Corona and Olympia. The fresh baked goodies, tea and “soda pop” bottled in antique 7-ounce bottles rounded out the experience, sure to be repeated in future years.

The town of Marlboro was in the throes of Northern Borders fever this spring, as the Movies from Marlboro hands-on film intensive (Potash Hill , Summer 2011) staged scenes in locations ranging from the Whetstone Inn to Mark and Megan Littlehales’ chicken coop. Despite technical difficulties including no snow, no cluster flies and not enough hours in a day, students and professionals in the program shot footage for the full-length movie and gained practical experience not available in the classroom. Learn more at www.northernbordersfilm.com. Photo by Willow O’Feral ’07

The town of Marlboro was in the throes of Northern Borders fever this spring, as the Movies from Marlboro hands-on film intensive (Potash Hill , Summer 2011) staged scenes in locations ranging from the Whetstone Inn to Mark and Megan Littlehales’ chicken coop. Despite technical difficulties including no snow, no cluster flies and not enough hours in a day, students and professionals in the program shot footage for the full-length movie and gained practical experience not available in the classroom. Learn more at www.northernbordersfilm.com. Photo by Willow O’Feral ’07

Despite the lack of snow, the cross-country ski team was an enthusiastic group this year. Several members participated in the Winter Break trip to St. Anne, Quebec, for a glimpse of what snow should look like, and another group returned to Morin Heights, Quebec, for Spring Break. Although the annual Wendell-Judd cup had to be postponed, and then cancelled on account of rain, the day before the scheduled event offered the best conditions of the winter, and a few members of the team had a spirited race of their own. Photo by Pearse Pinch

Despite the lack of snow, the cross-country ski team was an enthusiastic group this year. Several members participated in the Winter Break trip to St. Anne, Quebec, for a glimpse of what snow should look like, and another group returned to Morin Heights, Quebec, for Spring Break. Although the annual Wendell-Judd cup had to be postponed, and then cancelled on account of rain, the day before the scheduled event offered the best conditions of the winter, and a few members of the team had a spirited race of their own. Photo by Pearse Pinch

In April and May, the Marlboro community was treated to a plethora of plays by Marlboro seniors Logan Smith, Grace Leathrum, Mercedes Lake, Katherine Trahan and Samantha Hohl. From Grace’s Reedy Point, a fantastical journey full of intense visuals and multimedia displays, to Logan’s three short, compelling plays, called “Short Walks Down the Only Road There Is,” their work demonstrated the depth and range of student achievement in Marlboro’s theater program. Photo by Joanna Moyer-Battick

Everybody got up to dance when Negrura Peruana played at Ragle Hall in February. The concert was a celebration of the music and dance of Peru’s African population, a unique tradition that includes percussion instruments such as the cajón (wooden box drum), the quijada de burro (jaw of horse), the campana (cowbell), bongos and guitars. This year’s events also included a flamenco concert and a Latin American film festival, complementing the Spanish language curriculum on campus. Photo by Alek Jaunzemis

Worthy of note

“I didn’t plan to be the president of a small liberal arts college in Vermont,” wrote President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell in an article in the February 26 issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education. “I didn’t expect to fall in love when I drove up the hill to Marlboro College to meet the members of this intellectual and creative community.” In the article, titled “Two Nontraditional Presidents Speak Out: We Bring with Us a Healthy Impatience,” Ellen shared her perspective on the benefits and challenges of being a college president who comes from a nonacademic background. Her editorial was paired with one from James Danko, president of Butler University, also among the 13 percent of “nontraditional” presidents.

“I’m bringing my background in medical anthropology into my personal experiences in Nepal and the experiences shared with me through narratives,” said senior Cailin Marsden (right), who is doing her Plan on cross-cultural approaches to childbirth. She spent the fall semester in Nepal on a program with the School for International Training, exploring the history and socioeconomics of Tibetan refugee communities. For her independent project, she interviewed village families about their birth experiences. “I’m interested in learning about the greater health care system in Nepal and what maternal health care looks like, especially in rural settings.”

“I’m bringing my background in medical anthropology into my personal experiences in Nepal and the experiences shared with me through narratives,” said senior Cailin Marsden (right), who is doing her Plan on cross-cultural approaches to childbirth. She spent the fall semester in Nepal on a program with the School for International Training, exploring the history and socioeconomics of Tibetan refugee communities. For her independent project, she interviewed village families about their birth experiences. “I’m interested in learning about the greater health care system in Nepal and what maternal health care looks like, especially in rural settings.”

Art faculty members Tim Segar and Cathy Osman presented a show of their work in January and February at the Catherine Dianich Gallery in Brattleboro. Tim shared more painting and drawing than usual, along with two bronze castings, while Cathy showed paintings on clay board and a relief sculpture. Their show overlapped with “Four Eyes: Art from Potash Hill,” a show including Cathy, Tim, photography professor John Willis and ceramics professor Martina Lantin, at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center (Potash Hill, Winter 2012). Tim said, “The two shows combined provided a unique opportunity to see a broad range of work by these artists made at various times over their careers.”

In April, philosophy professor William Edelglass gave the keynote address at Indiana University Southeast, part of their yearlong program on climate change, as well as a talk on Indian Buddhist philosophy. His address was called “Are We Morally Responsible for Climate Change?” “Even if the consequences of my own daily actions are negligible, I bear responsibility for the suffering that results from climate change when cumulatively the consequences of our actions are catastrophic,” William said. This is also the subject of his chapter in Facing Nature: Levinas and Environmental Philosophy, a book he co-edited, published by Duquesne University Press this year. William was also recently elected to the executive committee of the International Association of Environmental Philosophy.

“I realized that if I’m going to be studying international journalism as a means of human rights observation and democracy, I should probably get out of the United States,” said junior Sean Pyles (right). He spent the fall 2011 semester at John Cabot University, an American school based in Rome, taking classes in Writing for Advocacy and Television and Democracy. “The latter was essentially a crash course in the corruption of Italy’s media and the life of Silvio Berlusconi,” said Sean, who was in Italy when the prime minister was ousted. “I was feeling frustrated with the lack of democratic media around me, so I started a newspaper as a backlash. I learned the impact of journalistic activism and the importance of a free media for a functional democracy.”

Senior Cait Charles spent the fall 2011 semester in Nepal, studying Buddhism at a school located in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery, with some of the classes taught by accomplished scholar-monks. She followed this with a trip to India to visit Buddhist pilgrimage sites, including Bodhgaya, where the Buddha reportedly attained enlightenment. “I attended the 32nd Kalachakra, an event during which the Dalai Lama gives 11 days of teachings, rituals and empowerments,” said Cait. “It was ridiculously crowded; hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world came and flooded this tiny town that normally holds 30,000 people.” She spent the rest of the spring and summer visiting “ecovillages” in Thailand and Europe, part of her Plan research on the social, ecological, economic and cultural/worldview dimensions of sustainability.

In April, Susie Bellici (right) traveled to Iraq, under the auspices of the state department and World Learning, to facilitate training at a conference for the Iraqi Young Leaders Exchange Program. IYLEP is a program that enables Iraqi students to study at American institutions, develop leadership skills and build action plans to strengthen the future of Iraq. “Training from 8 to 5 was tiring, but these students were amazingly inspiring,” said Susie, who is the associate director of world studies at Marlboro. “They are ranked in the top 1 percent of Iraqi university students—for activism, civic engagement and academics—so their conversations were thoughtful, passionate and knowledgeable. I was privileged to be there.”

In April, Susie Bellici (right) traveled to Iraq, under the auspices of the state department and World Learning, to facilitate training at a conference for the Iraqi Young Leaders Exchange Program. IYLEP is a program that enables Iraqi students to study at American institutions, develop leadership skills and build action plans to strengthen the future of Iraq. “Training from 8 to 5 was tiring, but these students were amazingly inspiring,” said Susie, who is the associate director of world studies at Marlboro. “They are ranked in the top 1 percent of Iraqi university students—for activism, civic engagement and academics—so their conversations were thoughtful, passionate and knowledgeable. I was privileged to be there.”

“I use photography, teaching and working with others as a means to try and see how I fit into the world, attempting to share with others in our search for value and meaning,” said John Willis, photography professor. His presentation in April, “How Might We Use Artistic Practice in Service?” was part of an academic speaker series called Art, Empathy and Social Change, held at Landmark College this spring semester. “I believe I gain as much as, if not more than, my subjects by spending time with them and collaborating within the artistic process. I only hope my presence and work can also be beneficial to those I work with.” Philosophy professor Meg Mott was featured in February, with a talk about extending rights to natural objects titled “On the Emancipation of Eagles."

In April, the annual Tolkien conference at the University of Vermont brought J.R.R. fans from around New England to learn from eminent scholars about “Tolkien’s Bestiary.” These scholars included Marlboro sophomore Ray Saxon (right), who presented a paper titled “Manwë’s Messengers: The Role of Eagles in Middle Earth.” “I found that there are many commonly held misconceptions about the eagle’s role in Tolkien’s stories,” said Ray, whose paper explored the author’s true intentions in the matter. “The audience was very receptive, despite the fact that I was an undergraduate speaking alongside professors and independent scholars. I am so honored to have been given this opportunity, and proud to have represented Marlboro College.”

In April, the annual Tolkien conference at the University of Vermont brought J.R.R. fans from around New England to learn from eminent scholars about “Tolkien’s Bestiary.” These scholars included Marlboro sophomore Ray Saxon (right), who presented a paper titled “Manwë’s Messengers: The Role of Eagles in Middle Earth.” “I found that there are many commonly held misconceptions about the eagle’s role in Tolkien’s stories,” said Ray, whose paper explored the author’s true intentions in the matter. “The audience was very receptive, despite the fact that I was an undergraduate speaking alongside professors and independent scholars. I am so honored to have been given this opportunity, and proud to have represented Marlboro College.”

Spanish language professor Rosario de Swanson’s work on the literature of Equatorial Guinea (Potash Hill, Summer 2011) has been published as part of a United Nations Project to redress the rights of Afrodescendants, as people of African descent are called in Latinoamerica. Afrodescendencia: Aproximaciones contemporáneas desde América Latina y el Caribe recovers much of the forgotten history of these populations in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Rosario’s article examines women’s oppression in Ekomo, the first novel written by a woman in Equatorial Guinea. “My article is intended to shed light within Latin America on the literature, culture and arts of Equatorial Guinea,” said Rosario. “This is important because many of the slaves brought to Latin America came from the general region where Guinea is located.”

“A dance student at Marlboro is not like a dance student anywhere else,” said Cookie Harrist ’12 (right), who was chosen for a national conference gala performance at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. “We constantly question why we dance the way we dance.” The solo dance Cookie choreographed, titled “Present Present Present,” is an ambitious three-part piece that peels back the layers of artifice separating dancer from audience. Cookie brought “Present Present Present” to the 2012 National College Dance Festival, held on May 25 to 27, a biennial event showcasing the outstanding quality of choreography and performance created on college and university campuses across the country.

“A dance student at Marlboro is not like a dance student anywhere else,” said Cookie Harrist ’12 (right), who was chosen for a national conference gala performance at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. “We constantly question why we dance the way we dance.” The solo dance Cookie choreographed, titled “Present Present Present,” is an ambitious three-part piece that peels back the layers of artifice separating dancer from audience. Cookie brought “Present Present Present” to the 2012 National College Dance Festival, held on May 25 to 27, a biennial event showcasing the outstanding quality of choreography and performance created on college and university campuses across the country.

Hot on the heels of Drew Tanabe ’12, who was in Japan when it was rocked by the tsunami and resulting nuclear disaster last year (Potash Hill, Summer 2011), three students pursued their studies in Japan this year. In the fall semester, senior Gordie Morse went to Nagasaki and stayed with a host family while going to classes at the Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies. He attended daily Japanese language classes taught entirely in Japanese, by native speakers, as well as courses on Japanese history, culture, society and business management. “While Nagasaki is a city, it’s not as bustling or crowded as major cities in the United States, so it was a comfortable place to live in,” said Gordie. “I have great memories of talking to the native Japanese who lived there; I gained an appreciation for how foreigners are viewed in their communities and how their society differs from our own.” Meanwhile, senior Dane Fredericks was in Kyoto, the center of traditional culture in Japan, brimming with 2,000 Buddhist temples and monasteries. He participated in Antioch Education Abroad’s program on Japanese Buddhist traditions, which included learning some Japanese and exploring the diverse cultural expressions of Japanese Buddhism, from flower arranging to meditation. Dane’s independent research project focused on the burakumin, descendants of outcast communities from the feudal era who continue to be stigmatized and discriminated against. “People there prefer not to talk about them,” said Dane. “It’s all swept under a rug.” Senior Alek Jaunzemis (below) lived in Tokyo, splitting his time between attending classes at Temple University’s Japan campus and traveling all over Japan researching his Plan of Concentration on Japanese baseball. “I set myself some ambitious goals, such as interviewing players and journalists as well as representatives from the professional league, and I met most of them,” said Alek. “My favorite adventures included getting a press badge for the Tokyo Dome, which allowed me to interview players in the dugout during their practice, and catching an autographed, game-winning ball at a game in Chiba.”

For more information, see:

For more information, see:

Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

Cailin Marsden

William Edelglass

Susie Bellici

Rosario de Swanson

Cookie Harrist

Or be sure to get the latest scoop on Potash Hill at these sites:

Potash Phil

Facebook

YouTube

Twitter