Winter 2013

Editor's Note

“I think that the most important thing is to cherish your place,” said Shigeatsu Hatakeyama, a Japanese oyster farmer helping to rebuild his community after the 2011 tsunami. Hatakeyama’s story of resiliency is just one of those recounted by alumnus Drew Tanabe in his article “The Sea and the Forest Are Lovers.”

Resiliency has been a sort of theme at Marlboro this year, which started with an orientation reading of Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and discussion of “community, land and resilience.” It continues with this issue of Potash Hill, from an article by Gary Johnson about computer models of ecosystem services to the personal resilience evoked in an excerpt from Deni Béchard’s recent memoir, Cures for Hunger. Even history professor Adam Franklin-Lyons’ work on medieval mail couriers indicates a surprising degree of physical resilience long before running shoes were invented.

As always, we are interested in hearing your news and spirited reactions to this issue of Potash Hill. You can see letters in response to the last issue on page 45. —Philip Johansson, editor

Front cover: “After the Flood,” a work in recycled sewing patterns, oil, glue and balsa wood by art professor Cathy Osman. Photo by Timothy Segar

Discovering Fire

By Deni Béchard ’97

Photos by Thea Cabreros '13

In Cures for Hunger, Deni Béchard relates the story of growing up in British Columbia with a reckless father who has a mysterious past. In this excerpt Deni’s mother has left his father and moved to Virginia, but he can’t escape the feeling that his father holds the key to understanding himself.

Another card had arrived. It bore glittery words, “Thinking About You.” Inside was his number, nothing else. As if in a movie about prison, I felt like an inmate who receives a gift in which the means of escape are hidden. I left the house and went down the highway to the 7-Eleven.

A storm was blowing in, the sky dark and the power lines swaying. Trucks slowed and chugged into turns where the highways intersected, and after I dialed collect, his voice came thinly onto the line.

A storm was blowing in, the sky dark and the power lines swaying. Trucks slowed and chugged into turns where the highways intersected, and after I dialed collect, his voice came thinly onto the line.

We hadn’t spoken in months. He sounded different, reserved and unsure of himself, nothing like what I’d imagined since my mother had confessed his crimes to us.

He asked how I was, and I told him, “I’m okay. I’m just sick of school.”

“Oh,” he said. He asked how my brother and sister were, and I said, “Okay.” I talked a bit about rebuilding an old motorcycle I’d found in the barn where my mother kept her horses and a leather jacket I wanted. But then I ran out of things to say and we were silent for so long that I knew I had to tell him, that I had to share the only thing I could think about.

“Bonnie told me.”

“She told you what?”

“About”—I said—“about your crimes.”

He didn’t speak.

Clouds were moving in, drawing evening with them.

“What did she tell you?”

“She didn’t say much. I was the one who asked. I guess I already knew.”

“You already knew what?”

“That you’d been to jail. I was proud of you. She said you robbed banks.”

Again the long silence. Wind blew through the dust of the parking lot, knocking a crushed Styrofoam cup against the brick wall.

“She said that?” he asked, softly.

“I want to know about what you did.”

“What I did?”

“What I did?”

“I want to know everything. It’s amazing. No one else has a father like you.”

He was breathing into the receiver.

“What do you want to know?”

“About the banks. Did you only rob banks?”

“No.”

“What else did you rob?”

“I . . . .” He sighed. “Lots of things.”

“Like what?”

“You want to know about this? You’re proud?”

“It’s amazing. I think it’s amazing.”

I’d been almost panting, my heartbeat too fast. I sensed how much of a stranger he was. Four years had gone by, and I’d imagined him as he was before, living in the same house, driving the same car. But from the way he spoke, the care with which he chose his words, I knew he’d changed.

“I robbed banks,” he said. “It’s true. I robbed a lot of banks. And jewelry stores.”

“How many?”

“Maybe . . . I don’t know . . . maybe fifty banks. Armed robbery wasn’t a big deal. It was easy. I only did one bank burglary. That’s different.”

“What do you mean?”

“Burglary is when you go in at night and take everything. You go into the vault. Robbery is with a gun. Anyone can do that. But burglary takes brains.”

The image of him with a gun, robbing a bank as if it were nothing, impressed me, but burglary didn’t interest me at all.

“What about the jewelry stores?”

“Lots of them,” he said as if to please me. “I unloaded what I got with the mob.”

“Lots of them,” he said as if to please me. “I unloaded what I got with the mob.”

“The mob?”

“It’s not that big of a deal. It’s pretty common. I probably robbed—I don’t know— fifty jewelry stores, too. It was like a job.”

His voice became hoarse, and he coughed. I asked how bank robbery worked, and he told me about surveillance, knowing what time the armored truck came on payday. That’s when the tellers had more money. He hesitated, clearing his throat, and said, “Anyway.”

I could hardly breathe, hardly think of what to ask next. I had so many questions. I wanted him to speak, but he grew silent. Then the words came out of my mouth.

“Have you ever killed anyone?”

Rain had begun to fall, striking up the parking lot dust, the sky flat and low and gray, the wind strong.

“No,” he said finally, his voice so hoarse he was almost whispering. “Listen, Deni, I got out of crime because of you guys. I wanted a family. I didn’t want to go back to jail and not see my children. That’s why I stopped.”

“But it’s amazing. I think it’s amazing. No one else has a father like you.”

The downpour began in force, gusting under the overhang, soaking me where I huddled at the phone. Lightning flared beyond the highway, illuminating the cluttered rooftops of a subdivision. Thunder shook the ground, and the line went dead.

I hung up and pulled my jean jacket over my head and ran home.

Deni Béchard’s first novel, Vandal Love, won the 2007 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. He also writes articles, stories and translations for a number of magazines and newspapers.

Fragments of Reality

“The reality of the photograph is not proportionate to the truth in it,” said senior Thea Cabreros, who is working on her Plan of Concentration in photography and literature. “I feel that I have arrived somewhere when the contradictions of the photographic medium engage with the paradox of the project.” In her reading, Thea is comparing the often contradictory ethical views of Albert Camus and Fyodor Dostoevsky, but it is through her photography that she is more freely able to explore and confront the issues of constructed meaning. “When I take a photograph I am always (secretly) striving toward the utopian goals of perfection and unity. Of course, this refuses to be captured.”

“The reality of the photograph is not proportionate to the truth in it,” said senior Thea Cabreros, who is working on her Plan of Concentration in photography and literature. “I feel that I have arrived somewhere when the contradictions of the photographic medium engage with the paradox of the project.” In her reading, Thea is comparing the often contradictory ethical views of Albert Camus and Fyodor Dostoevsky, but it is through her photography that she is more freely able to explore and confront the issues of constructed meaning. “When I take a photograph I am always (secretly) striving toward the utopian goals of perfection and unity. Of course, this refuses to be captured.”

The Writing Life: An Interview with Deni Béchard

Potash Hill: You grew up in an unusual and, let’s say, at times problematic family. How do you think your upbringing has influenced your writing?

Deni Béchard: I think that my childhood gave me an interest in subjects that have been present in my writing for a long time: violence, displacement, mysticism, the experience of the outsider, the transformative power of art and just about any sort of extreme behavior. Also, from a young age, I used reading and writing to create a sense of continuity and coherence in my life, and this has become a theme I’ve often explored: the way we use stories to create meaning and fashion identities.

PH: In Cures for Hunger your father tells some truly amazing stories that seem hard to believe. To what degree do you believe them, and what effort did you make to fact-check?

DB: I think that his stories are largely true, though I’m sure that he often exaggerated or adapted them based on whatever he was trying to convey in that particular moment. He retold them often, and depending on his mood or what had happened recently in his life, he emphasized certain details. He might also have claimed to have robbed more banks and jewelry stores than he actually did, but I’m not sure. Most robberies are thought to be committed by serial bank robbers, so 50 doesn’t sound like a lot when we consider that he made a living as a criminal for more than a decade. As for fact-checking, I didn’t do any. A factual account of my father’s life isn’t of use to anyone, and he used so many different names that I’m not sure it could be had. Rather, I wanted to write about the influence that his character and his stories (true or not) had on me, and what it was like to grow up with a bank robber for a father. As a point of interest, Maisonneuve magazine ran an excerpt, and their fact-checker found an article that almost perfectly matched my father’s account of his 1967 burglary in Hollywood.

DB: I think that his stories are largely true, though I’m sure that he often exaggerated or adapted them based on whatever he was trying to convey in that particular moment. He retold them often, and depending on his mood or what had happened recently in his life, he emphasized certain details. He might also have claimed to have robbed more banks and jewelry stores than he actually did, but I’m not sure. Most robberies are thought to be committed by serial bank robbers, so 50 doesn’t sound like a lot when we consider that he made a living as a criminal for more than a decade. As for fact-checking, I didn’t do any. A factual account of my father’s life isn’t of use to anyone, and he used so many different names that I’m not sure it could be had. Rather, I wanted to write about the influence that his character and his stories (true or not) had on me, and what it was like to grow up with a bank robber for a father. As a point of interest, Maisonneuve magazine ran an excerpt, and their fact-checker found an article that almost perfectly matched my father’s account of his 1967 burglary in Hollywood.

PH: You wrote your first draft of this memoir soon after your dad passed away, in 1995. What has been your process for completing it in the meantime, and how has it changed?

DB: The memoir in its current form barely resembles the book that I wrote immediately after his death. For about a decade, I worked on it with the intention of making it into a novel before I accepted that I was writing a memoir. Though some of the material from the various versions is still present, the book in its current form took shape during a winter that I spent in Kabul. I was struggling to write about Afghanistan, and one day, standing on the roof of my apartment, it occurred to me that I was failing to see the joy in people’s lives and was focusing excessively on hardship and failure. I thought back to the memoir and realized that I hadn’t told that story properly either, that even though my childhood was chaotic, I’d enjoyed it—in fact, largely because it was so chaotic. Things that happened later overshadowed that, and I went back and rewrote the book trying to recall how I’d felt as a child and the solutions I’d found growing up. The solutions of youth often seem obvious as we get older, but they have the power of revelation to the child.

PH: How has your perception of your father changed as a result of writing Cures for Hunger?

DB: I think that writing the memoir made me see him as a much more complete and nuanced person. It forced me to examine how he changed and the details of his character, and increasingly, I saw that I hadn’t fully understood him—that, in many ways and despite his flaws, I was the culprit in several parts of the story.

PH: The book includes some touching anecdotes from your years at Marlboro. How did your time here help shape your writing in general and/or this book in particular?

DB: Marlboro offered me a sanctuary. I’d been bouncing from home to home, trying to direct my ambitions, and being at Marlboro both grounded me and helped me develop my goals. As for writing, I had the time, encouragement and freedom to experiment with language and form, and to begin finding my voice.

PH: What are your plans for any upcoming writing projects?

DB: I am currently finishing a nonfiction book about a group of conservationists working in the Congo rainforest, and it’s due out in 2013. I also have a novel about Afghanistan that I’ve been working on for a while, and I hope to go back to that full time in a few months. In general, I would like to alternate between nonfiction and fiction. Fiction is my first love, but nonfiction puts me in situations that I wouldn’t otherwise experience and that make me see the world differently. Also, finding narrative solutions in nonfiction makes me think more creatively about fiction, and vice versa.

Ring Around the Moon

Poems by Ellen McCulloch-Lovell

After Su Tung P’o

My second story window is green

Filled with fresh maple leaves

And sun falls below where day lilies

Along the roadside wave and fade.

How soon the earth swings after solstice

And the sun past dinner fails.

Come now, close your book,

There will be dark enough and soon

To sit and study by your lamp.

First Frost

Dark time, it’s coming–

Ring around the moon,

Fire in the stove,

Plants in, herbs up;

First frost tonight.

Soup in the bowls and

Blankets on the bed.

Sun sinking early,

Sooner night, deeper in.

Stars cast in vast array.

Green cells must freeze

Between midnight and the day,

Season of waiting, season of leaving.

Crying overhead. Dark, dark.

The great gray wings

stroke open the great gray sky.

Under the Black Glass

I can’t see out:

the hemlocks, birches

gone with that sliced moon

I saw before asleep.

The flannel on my face

proves I’m in bed: alright.

All else has disappeared.

The mind

under cover-lid

does not see yet

why trust this day.

Most of the Marlboro community knows Ellen McCulloch-Lovell as college president, and perhaps as a supporter of the arts through her past work as executive director of both the Vermont Arts Council and President Clinton’s Committee on Arts and Humanities. Fewer know her work as a poet, including a collection of poems titled Gone, published by Janus Press in 2011. Ellen completed her MFA in creative writing from Warren Wilson College in 2012, and taught a class at Marlboro last fall called The Poetry of Witness.

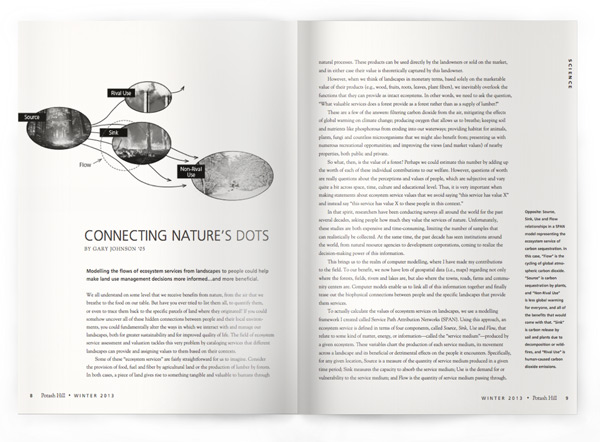

Connecting Nature’s Dots

By Gary Johnson ’05

Modelling the flows of ecosystem services from landscapes to people could help make land use management decisions more informed…and more beneficial.

We all understand on some level that we receive benefits from nature, from the air that we breathe to the food on our table. But have you ever tried to list them all, to quantify them, or even to trace them back to the specific parcels of land where they originated? If you could somehow uncover all of these hidden connections between people and their local environments, you could fundamentally alter the ways in which we interact with and manage our landscapes, both for greater sustainability and for improved quality of life. The field of ecosystem service assessment and valuation tackles this very problem by cataloging services that different landscapes can provide and assigning values to them based on their contexts.

Some of these “ecosystem services” are fairly straightforward for us to imagine. Consider the provision of food, fuel and fiber by agricultural land or the production of lumber by forests. In both cases, a piece of land gives rise to something tangible and valuable to humans through natural processes. These products can be used directly by the landowners or sold on the market, and in either case their value is theoretically captured by this landowner.

However, when we think of landscapes in monetary terms, based solely on the marketable value of their products (e.g., wood, fruits, roots, leaves, plant fibers), we inevitably overlook the functions that they can provide as intact ecosystems. In other words, we need to ask the question, “What valuable services does a forest provide as a forest rather than as a supply of lumber?”

These are a few of the answers: filtering carbon dioxide from the air, mitigating the effects of global warming on climate change; producing oxygen that allows us to breathe; keeping soil and nutrients like phosphorous from eroding into our waterways; providing habitat for animals, plants, fungi and countless microorganisms that we might also benefit from; presenting us with numerous recreational opportunities; and improving the views (and market values) of nearby properties, both public and private.

So what, then, is the value of a forest? Perhaps we could estimate this number by adding up the worth of each of these individual contributions to our welfare. However, questions of worth are really questions about the perceptions and values of people, which are subjective and vary quite a bit across space, time, culture and educational level. Thus, it is very important when making statements about ecosystem service values that we avoid saying “this service has value X” and instead say “this service has value X to these people in this context.”

In that spirit, researchers have been conducting surveys all around the world for the past several decades, asking people how much they value the services of nature. Unfortunately, these studies are both expensive and time-consuming, limiting the number of samples that can realistically be collected. At the same time, the past decade has seen institutions around the world, from natural resource agencies to development corporations, coming to realize the decision-making power of this information.

This brings us to the realm of computer modelling, where I have made my contributions to the field. To our benefit, we now have lots of geospatial data (i.e., maps) regarding not only where the forests, fields, rivers and lakes are, but also where the towns, roads, farms and community centers are. Computer models enable us to link all of this information together and finally tease out the biophysical connections between people and the specific landscapes that provide them services.

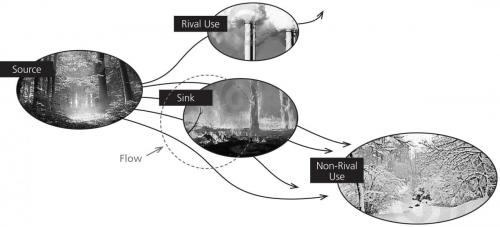

To actually calculate the values of ecosystem services on landscapes, we use a modelling framework I created called Service Path Attribution Networks (SPAN). Using this approach, an ecosystem service is defined in terms of four components, called Source, Sink, Use and Flow, that relate to some kind of matter, energy, or information—called the “service medium”—produced by a given ecosystem. These variables chart the production of each service medium, its movement across a landscape and its beneficial or detrimental effects on the people it encounters. Specifically, for any given location, Source is a measure of the quantity of service medium produced in a given time period; Sink measures the capacity to absorb the service medium; Use is the demand for or vulnerability to the service medium; and Flow is the quantity of service medium passing through.

At the beginning of a SPAN model, each location on a map is assigned a Source, Sink and Use value based on data from that location. This tells us which areas are capable either of providing a service or of benefiting from one. However, this does not tell us whether any services are actually delivered. To determine this, we simulate the movement of the chosen service medium—such as water for irrigation or flooding, soil for erosion control or sediment deposition, or bees and other insects for pollination—from their Source location to Use locations (i.e., you and me). Along the way, the service medium may be captured by Sinks, possibly reducing the overall amount reaching any Use destination. Think of it as a computer game for water, bees and other environmental benefits.

At the beginning of a SPAN model, each location on a map is assigned a Source, Sink and Use value based on data from that location. This tells us which areas are capable either of providing a service or of benefiting from one. However, this does not tell us whether any services are actually delivered. To determine this, we simulate the movement of the chosen service medium—such as water for irrigation or flooding, soil for erosion control or sediment deposition, or bees and other insects for pollination—from their Source location to Use locations (i.e., you and me). Along the way, the service medium may be captured by Sinks, possibly reducing the overall amount reaching any Use destination. Think of it as a computer game for water, bees and other environmental benefits.

Once our simulation is complete, we can represent the relationships between Sources, Sinks and Users graphically as a map of flow values. Locations on the map are connected by lines indicating the amount of service that successfully travels between them, connecting landscapes with human beneficiaries like a giant web. In this map we have a strong tool for analyzing the current value of a service in terms of its impacts on specific user groups.

To illustrate these abstract ideas with a concrete example, let us imagine using the SPAN framework to model an ecosystem service we are all very familiar with: scenic views. In this case, the service medium is light traveling from scenic landscape features (Sources)—for example, mountains, rivers, lakes or wetlands—to the eyes of people (Users). As they acquire more unobstructed views of the Source locations, these people experience an increase in their property values and other more subtle benefits. However, in addition to the scenic features, these same people may also see unsightly features (Sinks) such as industrial development, billboards and highways, which reduce the value of any view that passes through them. Our Flow simulation calculates all the visible Sources and Sinks to each User given the local topography (i.e., elevation data) and estimates the value to each user based on their mix of these views.

These same methods are being used to simulate the flow of water and flood mitigation, carbon dioxide and carbon sequestration, crops and food resources and many other benefits of nature in a variety of social contexts. By applying various computer modelling techniques to the problem of ecosystem service assessment and valuation, we can start to map out the connections within any given region between the particular landscapes that provide services and the people who receive them. One of the great strengths of the SPAN framework is that it provides a common definition and representation for the myriad ecosystem services that people are currently trying to model. This allows us to generate maps combining many different services that can be directly compared and analyzed.

Now armed with knowledge of these connections, decision-makers can actually take into account the effect on specific human groups of different land management or climate change scenarios. Being able to broadly identify who is likely to win and lose makes it possible to bring the people who will have the most at stake into decision-making discussions.

Our hope is that by bringing more of the spatially relevant details about ecosystem services into land use management decisions we can begin to support more holistic development or conservation plans. These plans will account for service sources, sink regions and the flow corridors crucial to the transmission of these benefits to human users. As this work is applied by government agencies and businesses, we stand to chart a better, more informed course for our future and that of our environment.

Gary W. Johnson Jr. graduated from Marlboro with a Plan in computer science and geoinformatics, and is currently a doctoral student in computer science at the University of Vermont. Last summer Gary received an award for “Best Student Paper” at the International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software in Leipzig, Germany, for his paper entitled “Modelling Ecosystem Service Flows under Uncertainty with Stochastic SPAN.”

New Meaning for Computer Language

“Machine translation was a dream of computational linguists for centuries, and within the last few decades it has become a reality,” said Elias Zeidan, who did a Plan of Concentration in computer science and linguistics. He compared web-based translators using a variety of metrics and found they were not yet viable alternatives to human translation. Elias also used statistics to analyze the Voynich manuscript, a mysterious, 15th-century book written in an unknown alphabet, looking for patterns or clues to the language. “Some of the glyphs look like the Latin alphabet, others look like Arabic numerals, and still others bear no resemblance to any known writing system. Based on statistical properties of natural language, I conjecture that the writing is a language—Middle German? Czech?—enciphered into this writing system.”

“Machine translation was a dream of computational linguists for centuries, and within the last few decades it has become a reality,” said Elias Zeidan, who did a Plan of Concentration in computer science and linguistics. He compared web-based translators using a variety of metrics and found they were not yet viable alternatives to human translation. Elias also used statistics to analyze the Voynich manuscript, a mysterious, 15th-century book written in an unknown alphabet, looking for patterns or clues to the language. “Some of the glyphs look like the Latin alphabet, others look like Arabic numerals, and still others bear no resemblance to any known writing system. Based on statistical properties of natural language, I conjecture that the writing is a language—Middle German? Czech?—enciphered into this writing system.”

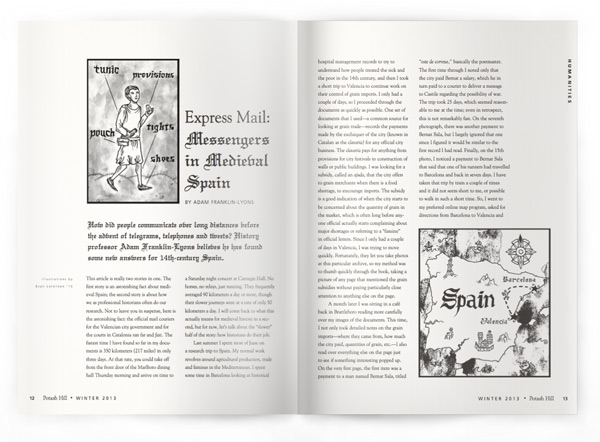

Express Mail: Messengers in Medieval Spain

By Adam Franklin-Lyons

Illustrations by Evan Lorenzen ’13

How did people communicate over long distances before the advent of telegrams, telephones and tweets? History professor Adam Franklin-Lyons believes he has found some new answers for 14th-century Spain.

his article is really two stories in one. The first story is an astonishing fact about medieval Spain; the second story is about how we as professional historians often do our research. Not to leave you in suspense, here is the astonishing fact: the official mail couriers for the Valencian city government and for the courts in Catalonia ran far and fast. The fastest time I have found so far in my documents is 350 kilometers (217 miles) in only three days. At that rate, you could take off from the front door of the Marlboro dining hall Thursday morning and arrive on time to a Saturday night concert at Carnegie Hall. No horses, no relays, just running. They frequently averaged 90 kilometers a day or more, though their slower journeys were at a rate of only 50 kilometers a day. I will come back to what this actually means for medieval history in a second, but for now, let’s talk about the “slower” half of the story: how historians do their job.

his article is really two stories in one. The first story is an astonishing fact about medieval Spain; the second story is about how we as professional historians often do our research. Not to leave you in suspense, here is the astonishing fact: the official mail couriers for the Valencian city government and for the courts in Catalonia ran far and fast. The fastest time I have found so far in my documents is 350 kilometers (217 miles) in only three days. At that rate, you could take off from the front door of the Marlboro dining hall Thursday morning and arrive on time to a Saturday night concert at Carnegie Hall. No horses, no relays, just running. They frequently averaged 90 kilometers a day or more, though their slower journeys were at a rate of only 50 kilometers a day. I will come back to what this actually means for medieval history in a second, but for now, let’s talk about the “slower” half of the story: how historians do their job.

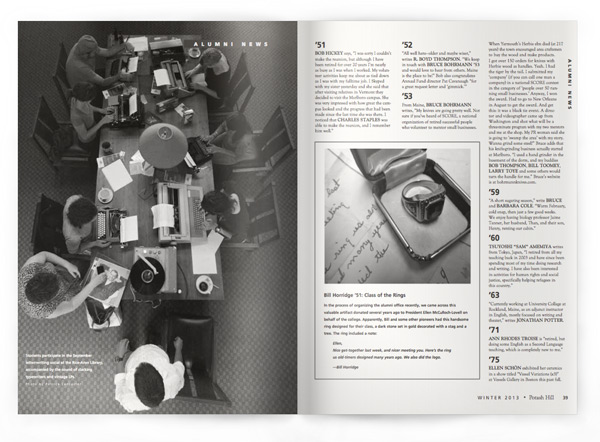

Last summer I spent most of June on a research trip to Spain. My normal work revolves around agricultural production, trade and famines in the Mediterranean. I spent some time in Barcelona looking at historical hospital management records to try to understand how people treated the sick and the poor in the 14th century, and then I took a short trip to Valencia to continue work on their control of grain imports. I only had a couple of days, so I proceeded through the documents as quickly as possible. One set of documents that I used—a common source for looking at grain trade—records the payments made by the exchequer of the city (known in Catalan as the clavaria) for any official city business. The clavaria pays for anything from provisions for city festivals to construction of walls or public buildings. I was looking for a subsidy, called an ajuda, that the city offers to grain merchants when there is a food shortage, to encourage imports. The subsidy is a good indication of when the city starts to be concerned about the quantity of grain in the market, which is often long before anyone official actually starts complaining about major shortages or referring to a “famine” in official letters. Since I only had a couple of days in Valencia, I was trying to move quickly. Fortunately, they let you take photos at this particular archive, so my method was to thumb quickly through the book, taking a picture of any page that mentioned the grain subsidies without paying particularly close attention to anything else on the page.

A month later I was sitting in a café back in Brattleboro reading more carefully over my images of the documents. This time, I not only took detailed notes on the grain imports—where they came from, how much the city paid, quantities of grain, etc.—I also read over everything else on the page just to see if something interesting popped up. On the very first page, the first item was a payment to a man named Bernat Sala, titled “oste de correus,” basically the postmaster. The first time through I noted only that the city paid Bernat a salary, which he in turn paid to a courier to deliver a message to Castile regarding the possibility of war. The trip took 25 days, which seemed reasonable to me at the time; even in retrospect, this is not remarkably fast. On the seventh photograph, there was another payment to Bernat Sala, but I largely ignored that one since I figured it would be similar to the first record I had read. Finally, on the 15th photo, I noticed a payment to Bernat Sala that said that one of his runners had travelled to Barcelona and back in seven days. I have taken that trip by train a couple of times and it did not seem short to me, or possible to walk in such a short time. So, I went to my preferred online map program, asked for directions from Barcelona to Valencia and got back 348 kilometers. At that point I was dumbfounded: a 700-kilometer journey in six days. This is the speed mentioned in the first paragraph, and it is clearly astonishing (if you know anyone who runs marathons, or even ultra-marathons, ask them—they will be shocked). From then on, I wrote down the details of every trip I found mentioned in payments to Bernat.

Among these trips, certain particulars started to become clear. Some trips, almost always during a crisis, were labeled “in a hurry.” These were usually important diplomatic communications, information about battles or (relevant to my research) runners sent to find out the price of grain in neighboring cities during a shortage. The initial trip I discovered to the court of Castile, probably held in the city of Burgos that year, does not say that they were sent in a hurry. The runner carried normal diplomatic letters and probably made the trip on a more or less regular basis to maintain communication between kingdoms. Faster trips represent emergencies, and the runners got paid accordingly. On the 25-day trip to Castile, the runner received four solidi per day—about double what an agricultural laborer made in a day—a good wage, but not extravagant. The runner who made the fantastic round trip to Barcelona in under a week? He received a salary of 22 solidi per day, plus 66 extra solidi as a reward for such a swift trip.

I have found no indication anywhere that they ever used horses. While I cannot be absolutely certain why, I know that horses are more expensive to keep and maintain. Additionally, horses provide the greatest speed advantage when used in stages (as later mail services would do—think pony express). Stages necessitate way stations and even greater infrastructure investment; they are also quite vulnerable in unstable political situations. I currently think that individual runners were more reliable and also less conspicuous, without sacrificing a great deal of speed.

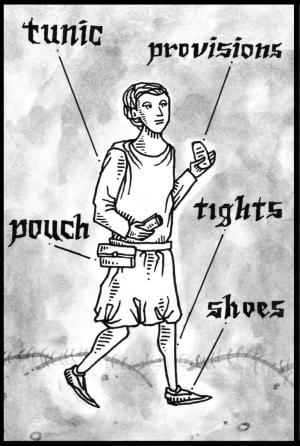

The runners carried only the smallest amount of weight. They ran in a tunic and tights with fairly ordinary shoes and carried a small pouch that held their letters as well as some sort of provisions. The clothing might not seem like ideal running gear, but compared to the heavy wool robes or cloaks worn by most people, even in hot weather, this outfit does begin to feel light and efficient. I know from another note in the clavaria that Bernat Sala purchased a large amount of candied fruit, “for the runners,” so I assume that provided the short-term energy needed to keep moving. The letters themselves, the primary reason for the journey and the speed, communicated all manner of information between officials, nobility and city leaders: news of war, official treaties, requests for purchase of grain, sometimes promissory notes to pay for major purchases or even bribes to influence events at court.

The runners carried only the smallest amount of weight. They ran in a tunic and tights with fairly ordinary shoes and carried a small pouch that held their letters as well as some sort of provisions. The clothing might not seem like ideal running gear, but compared to the heavy wool robes or cloaks worn by most people, even in hot weather, this outfit does begin to feel light and efficient. I know from another note in the clavaria that Bernat Sala purchased a large amount of candied fruit, “for the runners,” so I assume that provided the short-term energy needed to keep moving. The letters themselves, the primary reason for the journey and the speed, communicated all manner of information between officials, nobility and city leaders: news of war, official treaties, requests for purchase of grain, sometimes promissory notes to pay for major purchases or even bribes to influence events at court.

This small glimpse of so many letters moving back and forth illustrates an impressive amount of written communication; and their sometimes incredible speed challenges several assumptions I previously held about medieval Europe. It means that many more people would have had extensive access to recent information. People did not make decisions in a vacuum, unaware of what was going on even in the next village. I am fairly certain that during times of crisis the runners would not have been willing to share the contents of their communications with any old villager on their route (and come to think of it, I am not even certain they would have been able to read or even known the content of their messages). However, we do know that even illiterate citizens of towns knew a great deal about their town’s decision-making, laws and recent events. If official news from fairly great distances got included in this mix of knowledge that people had, it probably meant that the citizens knew about happenings in other regional centers as well. Through day-to-day market travel and more mundane communication, this means that people within as much as 40 miles of Valencia could also have known, to a greater or lesser degree, what was happening in the larger city, and by extension news from across much of Spain, on a fairly regular basis. Drawing circles of the spread of this knowledge around every sizable city in the region (Barcelona, Tarragona, Lleida, Tortosa) starts to cover a significant percentage of available space. It starts to feel like news could travel very far, very fast, and penetrate quite deeply within medieval society. All but the most remote villages could have had some sort of access to the goings on of the greater world on a semi-routine basis. This integration far exceeds what most medievalists I know would have considered normal.

To end back on my second story about historical research, I don’t know how true all this is. I only have around 15 trips by runners over the course of a six-month period. I will need to cover all of the payment books (around a dozen volumes, if I remember correctly), compiling a large list of trips and trying to answer a variety of questions: Did they go slower based on the season? Do they ever work with other runners hired by other cities? Who else did they communicate with besides their official handlers? How small of a city might have had professional runners? For now, I know none of those things. Future work will involve returning to my newly discovered source, but also hunting for new sources now that I have new questions. Truth be told, that hunt is why many of us go into history in the first place. Sure, writing up findings and the sense of accomplishment in finishing a project is great. But having unanswered questions—perhaps questions never before asked —that is what historical research is all about. That is exciting.

Adam Franklin-Lyons teaches history at Marlboro, with a particular interest in the economic, social and environmental history of the Middle Ages. This article is loosely based on a paper Adam plans to present at the Plymouth Medieval and Renaissance Forum in April.

Running from Bone Injury

Will Mikell ’13 first became intrigued with the bone physiology of running after reading Born to Run, the story of Mexico’s Tarahumara people who are known to run hundreds of miles without rest or injury. A premed student with a Plan of Concentration in biology and literature, Will explored recent research on the mineral bone density and skeletal health of marathon runners. His independent project compares barefoot runners to “shod” runners. “Running shoes have these big chunky soles, and they’re really quite detrimental to your skeleton,” said Will. “We didn’t evolve to include ‘heel strike’ in our running gait, and it actually causes damage to the shins, knees, hips, back, everywhere. A lot of the athletic injuries that you hear about now didn’t happen before thick-soled running shoes were introduced.”

Will Mikell ’13 first became intrigued with the bone physiology of running after reading Born to Run, the story of Mexico’s Tarahumara people who are known to run hundreds of miles without rest or injury. A premed student with a Plan of Concentration in biology and literature, Will explored recent research on the mineral bone density and skeletal health of marathon runners. His independent project compares barefoot runners to “shod” runners. “Running shoes have these big chunky soles, and they’re really quite detrimental to your skeleton,” said Will. “We didn’t evolve to include ‘heel strike’ in our running gait, and it actually causes damage to the shins, knees, hips, back, everywhere. A lot of the athletic injuries that you hear about now didn’t happen before thick-soled running shoes were introduced.”

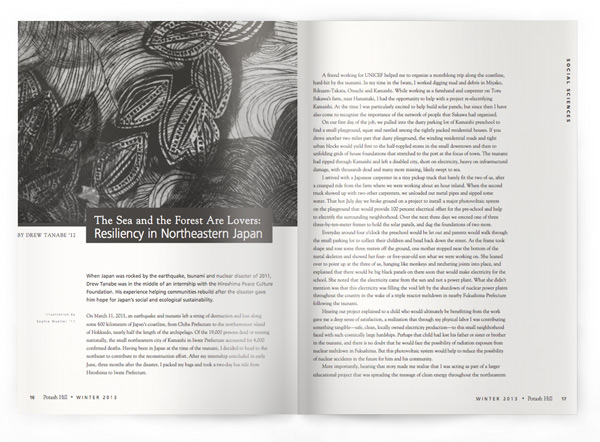

The Sea and the Forest Are Lovers: Resiliency in Northeastern Japan

By drew Tanabe ’12

Illustration by Sophie Mueller ’11

When Japan was rocked by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster of 2011, Drew Tanabe was in the middle of an internship with the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. His experience helping communities rebuild after the disaster gave him hope for Japan’s social and ecological sustainability.

On March 11, 2011, an earthquake and tsunami left a string of destruction and loss along some 600 kilometers of Japan’s coastline, from Chiba Prefecture to the northernmost island of Hokkaido, nearly half the length of the archipelago. Of the 19,000 persons dead or missing nationally, the small northeastern city of Kamaishi in Iwate Prefecture accounted for 4,000 confirmed deaths. Having been in Japan at the time of the tsunami, I decided to head to the northeast to contribute to the reconstruction effort. After my internship concluded in early June, three months after the disaster, I packed my bags and took a two-day bus ride from Hiroshima to Iwate Prefecture.

A friend working for UNICEF helped me to organize a monthlong trip along the coastline, hard-hit by the tsunami. In my time in the Iwate, I worked digging mud and debris in Miyako, Rikuzen-Takata, Otsuchi and Kamaishi. While working as a farmhand and carpenter on Toru Sakawa’s farm, near Hanamaki, I had the opportunity to help with a project re-electrifying Kamaishi. At the time I was particularly excited to help build solar panels, but since then I have also come to recognize the importance of the network of people that Sakawa had organized.

On our first day of the job, we pulled into the dusty parking lot of Kamaishi preschool to find a small playground, squat and nestled among the tightly packed residential houses. If you drove another two miles past that dusty playground, the winding residential roads and tight urban blocks would yield first to the half-toppled stores in the small downtown and then to unfolding grids of house foundations that stretched to the port at the focus of town. The tsunami had ripped through Kamaishi and left a disabled city, short on electricity, heavy on infrastructural damage, with thousands dead and many more missing, likely swept to sea.

I arrived with a Japanese carpenter in a tiny pickup truck that barely fit the two of us, after a cramped ride from the farm where we were working about an hour inland. When the second truck showed up with two other carpenters, we unloaded our metal pipes and sipped some water. That hot July day we broke ground on a project to install a major photovoltaic system on the playground that would provide 100 percent electrical offset for the pre-school and help to electrify the surrounding neighborhood. Over the next three days we erected one of three three-by-ten-meter frames to hold the solar panels, and dug the foundations of two more.

I arrived with a Japanese carpenter in a tiny pickup truck that barely fit the two of us, after a cramped ride from the farm where we were working about an hour inland. When the second truck showed up with two other carpenters, we unloaded our metal pipes and sipped some water. That hot July day we broke ground on a project to install a major photovoltaic system on the playground that would provide 100 percent electrical offset for the pre-school and help to electrify the surrounding neighborhood. Over the next three days we erected one of three three-by-ten-meter frames to hold the solar panels, and dug the foundations of two more.

Everyday around four o’clock the preschool would be let out and parents would walk through the small parking lot to collect their children and head back down the street. As the frame took shape and rose some three meters off the ground, one mother stopped near the bottom of the metal skeleton and showed her four- or five-year-old son what we were working on. She leaned over to point up at the three of us, hanging like monkeys and ratcheting joints into place, and explained that there would be big black panels on there soon that would make electricity for the school. She noted that the electricity came from the sun and not a power plant. What she didn’t mention was that this electricity was filling the void left by the shutdown of nuclear power plants throughout the country in the wake of a triple reactor meltdown in nearby Fukushima Prefecture following the tsunami.

Hearing our project explained to a child who would ultimately be benefitting from the work gave me a deep sense of satisfaction, a realization that through my physical labor I was contributing something tangible—safe, clean, locally owned electricity production—to this small neighborhood faced with such cosmically large hardships. Perhaps that child had lost his father or sister or brother in the tsunami, and there is no doubt that he would face the possibility of radiation exposure from nuclear meltdown in Fukushima. But this photovoltaic system would help to reduce the possibility of nuclear accidents in the future for him and his community.

More importantly, hearing that story made me realize that I was acting as part of a larger educational project that was spreading the message of clean energy throughout the northeastern disaster zone. Sakawa, a committed permaculture farmer and advocate for green lifestyles and technologies in Japan, did much more than run the farm where I was working that July. He was connected with a group of social entrepreneurs, farmers, agricultural workers, carpenters and electronics store owners who were mobilizing funds, labor, expertise and equipment to provide renewable power to municipal buildings along the coast of Iwate. Among other projects, Sakawa and partners had recently finished a 100-kilowatt installation at an elementary school in the nearby hard-hit city of Rikuzen-Takata. By placing these installations in small community settings, Sakawa and his associates were not merely providing vitally needed electricity to hard-struck areas. They were bringing local community members into direct contact with clean technologies and the concept of small-scale distributed electricity generation.

Civic ecologists, like Keith Tidball and his colleagues at Cornell University, offer us a framework to understand the role of projects such as Sakawa’s solar electrification project in Kamaishi following disaster. They propose that all communities are part of a larger social-ecological system (SES): social systems (families, communities, populations, states, etc.) are nested within ecological systems (ecosystems, watersheds, landscapes, bioregions, biosphere). SES resilience theory builds on this foundation and asks what are the mechanisms by which such systems maintain their function and structure in the wake of disaster.

Civic ecologists, like Keith Tidball and his colleagues at Cornell University, offer us a framework to understand the role of projects such as Sakawa’s solar electrification project in Kamaishi following disaster. They propose that all communities are part of a larger social-ecological system (SES): social systems (families, communities, populations, states, etc.) are nested within ecological systems (ecosystems, watersheds, landscapes, bioregions, biosphere). SES resilience theory builds on this foundation and asks what are the mechanisms by which such systems maintain their function and structure in the wake of disaster.

Social-ecological systems are characterized by feedback loops linking social and environmental responses. One example of such feedback is from an urban garden, which benefits both the social community and the ecological community. Urban gardens strengthen the tendency of the SES not only to filter water and manage storm runoff but also to build and maintain strong social ties. A healthy SES has an array of such positive feedback cycles and displays high resiliency—that is, the ability of a system to absorb shock and reorganize after shock while maintaining essentially the same structure, function and identity.

To a civic ecologist, Sakawa’s participation in the solar electrification project can be characterized by his ability to source skilled (the carpenter) and unskilled (me) labor and provide a staging area for regional projects in collaboration with others. His work would be considered a “community of practice” that has arisen in response to disaster. The role of communities of practice is vital to building SES resiliency because they act to collect and redistribute skills and knowledge among their members and the outside world. In the particular case of Sakawa’s project, a focus on ecologically centered activities provides a codependent link between social resiliency and ecological resiliency.

Another example of “community of practice” that I encountered was through an oyster farmer in Kesenuma, Miyagi Prefecture, named Shigeatsu Hatakeyama. For several years now Hatakeyama has been working with students from the University of Kyoto to illustrate the connections between the ocean and the mountains. After a red tide in the late 1980s endangered his oyster farm, he discovered that the source of the algal bloom was wastewater leaking into the local river. He began to work on cleaning up the river and the upper watershed through promoting tree plantings and other stewardship projects. Since that time he has noticed a slow but steady increase in both the quality of water in the river and ocean and the quality of the forest in the surrounding watershed. His work with reforestation has gained a following in Japan, as has his saying that “the sea and the forest are lovers” (mori wa umi no koibito).

While the tsunami deeply affected Hatakeyama and his community, he has been able to see the damage as potentially beneficial in the long run because new houses and community infrastructure will be built with sustainability in mind. “The tsunami cost many lives and countless jobs,” he said. “Many people ask why we still live here, but most of us can’t convince ourselves to move away to the cities. We still want to live on a hillside, where we can see the ocean and go out fishing. We were born and raised here, and we love our home. I think that the most important thing is to cherish your place.”

Now is the hour that northeastern Japan is facing the difficult issues of reconstruction. What industries should be rebuilt? What types of infrastructure best suit the needs of the coming century? How are communities reconstructed after such disruption and loss, particularly among the elderly? There are promising signs of recovery taking a turn in the direction of building social and ecological resiliency, but these are small fish in a large ocean of corporate wholesale redevelopment schemes. The choices that the people and government of Japan make over the coming years will stand as an example of what is possible in building a modern city from scratch. My hope is that they will take advantage of this rare opportunity to rebuild in a fashion that preserves and enhances the stability, integrity and beauty of the land and sea.

After graduating in May with a Plan of Concentration in politics and Asian studies, Drew Tanabe did a summer internship in the office of Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy. He now works for Secretary of the Senate Nancy Erickson, and is enjoying living on the other “hill.”

Disasters and Inequality

Japan’s earthquake and tsunami share more in common with disasters closer to home than you might imagine. “Natural disasters are essentially social events that reflect back to us the way we live and structure our communities,” said Kat Rickenbacker, Marlboro’s new professor of sociology. Kat’s research has focused on environmental sociology, but she also has a passion for disasters. “How do societies respond to disaster, and what does this tell us about the human condition?” asks Kat. “What makes certain communities more vulnerable to disaster, or more able to adapt after a disaster has occurred? I’m interested in how preexisting inequalities contribute to the severity of the disaster.” Her class last fall, Inequality and “Natural” Disasters, included looking at the impact of Tropical Storm Irene on local communities.

Japan’s earthquake and tsunami share more in common with disasters closer to home than you might imagine. “Natural disasters are essentially social events that reflect back to us the way we live and structure our communities,” said Kat Rickenbacker, Marlboro’s new professor of sociology. Kat’s research has focused on environmental sociology, but she also has a passion for disasters. “How do societies respond to disaster, and what does this tell us about the human condition?” asks Kat. “What makes certain communities more vulnerable to disaster, or more able to adapt after a disaster has occurred? I’m interested in how preexisting inequalities contribute to the severity of the disaster.” Her class last fall, Inequality and “Natural” Disasters, included looking at the impact of Tropical Storm Irene on local communities.

Return to Core Values: The Challenges of Marketing Marlboro in the 21st Century

By Alexia Boggs ’13

In an effort to boost lagging recruitment and retention, Marlboro College as an institution is looking at new marketing strategies. Rather than panicking or assigning blame, this is a time for problem-solving: as members of the Marlboro College community, we must help figure out how to energize student enrollment. Since our material resources are limited, we need to use them efficiently but also supplement them with the abundance of critical thinking resources that reside in the community. We will certainly take advantage of new ideas and new technologies that can adapt college marketing efforts to meet the standards of contemporary higher education. But it is my suspicion that in all this effort to problem-solve, we may be losing track of our purpose—to educate. And what a loss that would be.

Last spring, the college hired kor group, in collaboration with Maguire Associates and Libretto, a marketing team from Boston selected from several who each made presentations to the Marlboro community. After being selected, kor came to campus to meet the community, not just to collect the numbers and jot down the data but with a particular interest in getting to know students. They broke out into small groups at Town Meeting, asking individuals what they wanted people to know about Marlboro. They sat in on classes, attended lectures and play rehearsals, and tagged along on several of my campus tours. Over the course of their visit, I got to know the members of the kor group. I felt respected by them, enjoyed their company and felt confident that they would produce an excellent report on the college over the summer.

And they did. The “kor report,” as it has become known, thoroughly examines Marlboro College marketing and admissions strategies from a variety of angles. It is undeniably a useful document for our community, as it provides us with an outsider’s perspective. The kor report serves as a peer edit for Marlboro College. When a friend edits a paper for me, she can tell me what argument it seems like I am trying to make, so I can see if I am effectively communicating what I intend to. Similarly, the kor report can tell us what Marlboro College’s argument is, and from that we can determine to what extent we are communicating what we intend.

This move to revitalize Marlboro’s marketing effort has been controversial, of course. It seems to me that the controversy stems from the tension between a need to sustain the school and the desire to maintain its authenticity—the former viewpoint belonging largely to Marlboro, the institution, and the latter belonging to Marlboro, the community. This tension is substantial and has contributed to much internal reflection throughout the college, both the institution and the community.

This move to revitalize Marlboro’s marketing effort has been controversial, of course. It seems to me that the controversy stems from the tension between a need to sustain the school and the desire to maintain its authenticity—the former viewpoint belonging largely to Marlboro, the institution, and the latter belonging to Marlboro, the community. This tension is substantial and has contributed to much internal reflection throughout the college, both the institution and the community.

In the end, all of us share the desire to know what response, in terms of marketing efforts, will be best for the college. It is evident to me that the realistic need for marketing is one that we as a community can still come to terms with; most of the controversy on marketing Marlboro is not concerned with the question of whether or not to market, but the process and method that will be used. For example, this is the implication of a recently scrawled question on a dining hall whiteboard: “Are students at the kor of [Marlboro’s] marketing efforts?”

I for one do not deny the need for marketing at Marlboro, and I recognize that the kor group or the new marketing director we are hiring could be helpful to the school. However, we must be cautious and conscious of promoting appearances that distract us from our simple strengths, for appearances are not the point. And neither are students the point; they should not be “at the kor” of marketing. Education is at the core of the college, with faculty and students as the primary actors. As such, education should be at the center of our marketing efforts, and oh how simple that makes the marketing strategy—do what you do best: educate.

Keep it simple, Marlboro. We know that our purpose is education, which is the process of teaching and learning. Marlboro faculty are passionate about teaching (and learning); Marlboro students are passionate about learning (and teaching). We perform this function well, in both lean times and boom days, and the sublime nature of education at Marlboro is a boon to those who’ve witnessed its power. Marketing is a necessary measure to keep this noble purpose afloat, but first and foremost Marlboro should be in the business of education.

Alexia Boggs is a senior at Marlboro doing a Plan of Concentration in politics, specifically looking at how political systems channel tensions by circumventing notions of a good vs. evil dichotomy. This essay is adapted from Alexia’s article by the same title published in the October 2012 issue of The Citizen.

The marketing and communications team of kor group, Libretto and Maguire Associates was engaged last spring after a thorough search and proposal process involving representatives from all of Marlboro’s constituencies. In the intervening months, the kor group has worked closely with the admissions office to implement strategies designed to measurably improve the college’s recruitment efforts. “Marlboro is a thoughtful and studious community,” said the kor report. “It needs to put some stakes in the ground, claim its territory, be bold and confident in its messaging and unapologetic for what it offers.”

On & Off the Hill

New faculty members, new greenhouse, new library books, oh my! Say farewell to storied sociology professor Jerry Levy and learn what environmental studies looks like in China.

New faculty members, new greenhouse, new library books, oh my! Say farewell to storied sociology professor Jerry Levy and learn what environmental studies looks like in China.

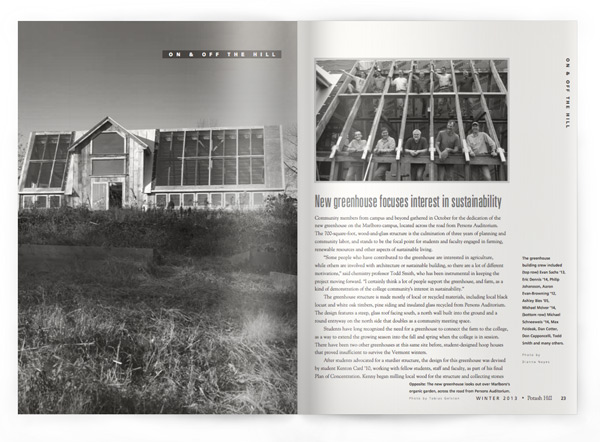

New greenhouse focuses interest in sustainability

Community members from campus and beyond gathered in October for the dedication of the new greenhouse on the Marlboro campus, located across the road from Persons Auditorium. The 700-square-foot, wood-and-glass structure is the culmination of three years of planning and community labor, and stands to be the focal point for students and faculty engaged in farming, renewable resources and other aspects of sustainable living.

“Some people who have contributed to the greenhouse are interested in agriculture, while others are involved with architecture or sustainable building, so there are a lot of different motivations,” said chemistry professor Todd Smith, who has been instrumental in keeping the project moving forward. “I certainly think a lot of people support the greenhouse, and farm, as a kind of demonstration of the college community’s interest in sustainability.”

The greenhouse structure is made mostly of local or recycled materials, including local black locust and white oak timbers, pine siding and insulated glass recycled from Persons Auditorium. The design features a steep, glass roof facing south, a north wall built into the ground and a round entryway on the north side that doubles as a community meeting space.

The greenhouse structure is made mostly of local or recycled materials, including local black locust and white oak timbers, pine siding and insulated glass recycled from Persons Auditorium. The design features a steep, glass roof facing south, a north wall built into the ground and a round entryway on the north side that doubles as a community meeting space.

Students have long recognized the need for a greenhouse to connect the farm to the college, as a way to extend the growing season into the fall and spring when the college is in session. There have been two other greenhouses at this same site before, student-designed hoop houses that proved insufficient to survive the Vermont winters.

After students advocated for a sturdier structure, the design for this greenhouse was devised by student Kenton Card ’10, working with fellow students, staff and faculty, as part of his final Plan of Concentration. Kenny began milling local wood for the structure and collecting stones for the foundation and retaining walls that year, and the structure has steadily grown since then with the help of other community members.

“Kenny was interested in architecture, but also in how communities use spaces,” said Todd. “So he was very interested in how the greenhouse might serve to enhance activity at the farm and bring other community members down to the farm to get involved.”

“A lot of people don’t know where the farm is. I’ve run into this pretty frequently,” said sophomore Simeon Farwell-Miller, the current farm manager. “I think that visibility has been a problem in the past, but with the construction of the greenhouse the farm will be much more apparent. And we’re planning to plant flowers and medicinal herbs and other attractive things in front of the greenhouse, which should make it even more eye-catching.”

The greenhouse dedication comes at a time when awareness of local foods and other sustainable practices is growing on campus. The dining hall, under the dedicated guidance of general manager Richie Brown, is increasingly buying its raw ingredients from local or organic sources. The Environmental Quality Committee is stepping up efforts to recycle and compost, and the Food Committee is working with the community to eliminate the use of disposable cups. The farm, benefitting from its first summer with two fully paid managers, has supplied fresh food to both the coffee shop and the dining hall.

The greenhouse dedication comes at a time when awareness of local foods and other sustainable practices is growing on campus. The dining hall, under the dedicated guidance of general manager Richie Brown, is increasingly buying its raw ingredients from local or organic sources. The Environmental Quality Committee is stepping up efforts to recycle and compost, and the Food Committee is working with the community to eliminate the use of disposable cups. The farm, benefitting from its first summer with two fully paid managers, has supplied fresh food to both the coffee shop and the dining hall.

A key rationale for the greenhouse has been to draw more faculty and students to use the farm as a class resource for teaching or research. Todd Smith, for example, has based his General Chemistry Lab on the production of biofuels, growing sunflowers on the farm to collect the seeds, extract the oil and manufacture fuel. Other applications could range from growing experiments to farm poetry.

The official ribbon-cutting at the dedication was performed by Don Capponcelli, college carpenter, whose work was instrumental in the greenhouse’s completion and who has been a tireless advocate for the project. Present at the dedication were Bob Allen, president of the Windham Foundation, and neighbor David White, both of whom generously supported the greenhouse project. Other supporters, not able to be present, include Charles J. and Susan J. Snyder, Dr. Suzanne Olbricht and Jon A. Souder ’73. Kenny was enthusiastically present at the celebration via Skype from Germany, where he was attending a graduate program in architecture.

Marlboro takes environmental studies to China

“It’s easy to forget how small the earth is when at Marlboro, where the air is clear and the trees are tall,” said writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard. “Being in China made us aware of how pervasive human influence can be.”

“It’s easy to forget how small the earth is when at Marlboro, where the air is clear and the trees are tall,” said writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard. “Being in China made us aware of how pervasive human influence can be.”

Kyhl was one of seven faculty and ten students who traveled to China for three weeks last summer to explore dimensions of environmental and social issues there. This was the last in a series of fruitful visits to Asia, including China, Japan, Vietnam and Cambodia, supported by two generous grants from the Freeman Foundation. The trip followed a seminar last spring called China’s Environmental Challenges, which laid the theoretical groundwork and practical background for the visit.

“The preparatory seminar helped us calibrate our expectations, but nothing prepared me for what we saw,” said economics professor Jim Tober, who has a special interest in environmental economics and policy. “One can read about rates of growth, construction booms, consumerism and so on, and still be totally taken aback by cities of 10 million, like Harbin, that seem to be materializing before our very eyes.”

Grant Li, professor of Chinese language, and Seth Harter, professor of Asian studies and history, were instrumental in making the trip rewarding through their logistical footwork and relevant knowledge. The group arrived in Beijing, a city of 20 million, and visited many of the nearby attractions, such as the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace and the Great Wall. But they also spent time meeting with local environmental agencies, activists and researchers, from the People’s University Legal Clinic for Pollution Victims to the Zhalong Crane Nature Reserve. At Heilongjiang University, in Harbin, they were joined by eight students of English, who acted as guides and translators and gave Marlboro students the opportunity to have home visits and other outings.

A highlight for Kyhl was the chance to reconnect with Chinese colleagues he had met when they were visiting scholars at University of Nevada, Reno. The reunion prompted a lively discussion at Beijing International Studies University, one of several opportunities for Marlboro students to talk about environmental issues on campuses in China.

Jim said, “There was much disagreement among students and faculty and others we met as to whether more substantive attention to environmental degradation would follow naturally from the production of wealth in China, such that the country could ‘afford’ improvements— after all, it was suggested to us, look at the same trajectory in U.S. history—or whether the rapidity and severity of decline called for a more aggressive response.” He found the Harbin Siberian Tiger Park a particularly fascinating insight into the public consumption of conservation and endangered species protection in China. Visitors to the park ride through caged areas to view tigers, ligers and lions, and feed them live animals for an extra price. “While the nominal purpose for the breeding program might be to reintroduce tigers into the wild, there has never been a reintroduction in China and it is not even clear that there is a reintroduction plan in place.”

“Environmental studies in China is even more complex because the systems at work are different than their American counterparts,” said junior Casey Chalbeck. “For me, to even begin to understand some of the environmental issues China is faced with required a strong and critical interdisciplinary approach that took me out of my intellectual comfort zone. Being able to study alongside such a diverse group of professors and students really facilitated this for me, and because of that I feel like a better student.”

Chinese partners host faculty

In July, Dean of Faculty Richard Glejzer joined Grant Li—who had stayed on at Heilongjiang University with three environmental studies trip students—and four more Marlboro students for a six-week language program (Potash Hill, Winter 2011). Together, the two Marlboro faculty members made great strides in establishing student exchange partnerships with both Heilongjiang and Jiamusi Universities.

In July, Dean of Faculty Richard Glejzer joined Grant Li—who had stayed on at Heilongjiang University with three environmental studies trip students—and four more Marlboro students for a six-week language program (Potash Hill, Winter 2011). Together, the two Marlboro faculty members made great strides in establishing student exchange partnerships with both Heilongjiang and Jiamusi Universities.

“Through our expanded international programming, funded in large part by the Christian Johnson Endeavor Foundation grant, we have been able to build up the infrastructure and awareness at Marlboro to welcome more international students,” said Richard. This includes Marlboro’s new English for Academic Purposes program, which gives second language speakers broad support for both written and spoken English, and other measures to make foreign students feel more at home.

“This trip was the first stage of what will be two valuable partnerships,” continued Richard. “Both universities highly value the academic model and liberal arts curriculum offered by Marlboro, and we look forward to welcoming their students.” The next stage in the partnership will be to welcome senior administrators from each university to Marlboro, starting with a visit from Heilongjiang in April.

New faculty express diverse points of view

By Christian Lampart ’16

“From my experience as both student and teacher, I have found that the most memorable learning often occurs outside the classroom, when one applies knowledge to practice,” says Marlboro’s new sociology professor Katherine Rickenbacker. “Kat” is one of three new professors made welcome by Marlboro College this fall, in the areas of sociology, French and physics, each of them bringing fresh perspectives to the community.

“From my experience as both student and teacher, I have found that the most memorable learning often occurs outside the classroom, when one applies knowledge to practice,” says Marlboro’s new sociology professor Katherine Rickenbacker. “Kat” is one of three new professors made welcome by Marlboro College this fall, in the areas of sociology, French and physics, each of them bringing fresh perspectives to the community.

“I aim to send my students into the community when possible, to bridge the gap between theory and the ‘real world,’” explains Kat, who taught Introduction to Sociology and Inequality and “Natural” Disasters this fall. “I also believe that learning happens most effectively when students feel a sense of ownership of the course.”

Kat didn’t always know she would be a sociologist. “I fell into it,” she reminisces with a smile. “I went through five different majors as an undergrad before I had to declare. First I started with English, because I wanted to be a poet, which obviously has more job prospects than sociology. I finally settled on sociology, because it just made sense to me. Once I started graduate school, everything became so interesting.”

Kat received her bachelor’s degree in sociology, with a minor in environmental science and policy, from Smith College. She earned her master’s and doctorate in sociology from Northeastern University, with an emphasis in environmental sociology and the sociology of disaster and vulnerability. Her dissertation, “City Roots: Grassroots efforts to build social and environmental capital in urban areas,” examines small-scale urban greening projects in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Kat is already applying her expertise in the area by joining Marlboro’s Environmental Quality Committee, which is responsible for facilitating environmental sustainability programs like recycling and composting on campus. She hopes to undertake some environmentally based projects with grassroots organizations in Brattleboro in the near future, continuing Marlboro’s service-learning pedagogy. As for teaching, Kat did not always know this was a strength.

“I almost left the program at Northeastern because one of the requirements was that you had to teach a class—just one,” Kat jokes. “I remember throwing up in the bathroom before my first class, because I was terrified of the 130 people sitting outside in that auditorium. But then I got hooked on it. Now it’s what I look forward to more than anything.” With a place as close-knit, yet independent, as Marlboro College, Kat is excited to discover alternative teaching methods to adjust for such a select group of students.

“Although I like the idea of small classes, I have never actually done this small,” marvels Kat, whose Introduction to Sociology class had only five students. “I think people here seem very interested in what they are doing and are really driven in whatever their individual projects are. Marlboro gives people who want to go to graduate school such an edge.”

Marlboro’s new French professor, Boukary Sawadogo, has global experience, to put it mildly. Born in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, “Abu,” has lived in Burkina Faso, where he grew up, as well as Ghana, Senegal, Iowa and Louisiana before finally ending up at Marlboro College.

Marlboro’s new French professor, Boukary Sawadogo, has global experience, to put it mildly. Born in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, “Abu,” has lived in Burkina Faso, where he grew up, as well as Ghana, Senegal, Iowa and Louisiana before finally ending up at Marlboro College.

“Iowa, Louisiana, Vermont,” Sawadogo jokes. “It looks just like a circle. Where I came from in Africa, it was really hot. When I came to Iowa—very hot; Louisiana—still pretty hot. Now I’m here in Vermont. We do not even have a word for ‘snow’ in Burkina Faso, only ‘ice.’”

Abu received his bachelor’s degree in foreign languages, tourism and business from the University of Dakar, Senegal. He later went on to earn a graduate diploma in international relations from the Institute of Diplomacy & International Relations in Burkina Faso and a certificate for film production assistant from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He received his doctorate in Francophone studies from the University of Louisiana. His dissertation, “Altérité dérangeante et innovante dans le cinéma ouest-africain francophone de. 1990 à 2005,” examines the representation of marginal groups in francophone-African cinema.

“Precisely, I worked on the representation of the ‘mad man,’ the so-called ‘crazy person’ in film,” Abu explains. In addition, he has looked at the representation of homosexuals and women in African films. “I cannot say that women are ‘marginal groups’ because they represent 52 percent of the population in Africa. But I am interested in what happened in popular culture 200 or 300 years ago that put the traditional representation of women, once really powerful figures, on the margin.”

In addition to teaching French language and Francophone literature, and conducting a “French table” at the Twilight Tea Lounge in Brattleboro on Saturday afternoons, Abu looks forward to exploring issues of immigration and colonialism with his students—and of course African cinema. He delights in discovering, analyzing and interpreting depictions of change in filmography. Through the careful study of films that express the contravention of societal norms, Abu hopes to spark an interest in social progress in his students.

“Marlboro is small. But it’s not small in ideas,” Abu perceives. “I think that’s what matters. In terms of ideas and in terms of perspectives, Marlboro has nothing to envy of a larger university.” Abu remarked on the level of openness, care and concern for his well-being that has been expressed by Marlboro faculty since his first visit to the college. From colleagues helping to find him an apartment to others checking in on him when he missed soccer practice, he has felt very warmly welcomed.

“People were constantly checking up on me. I felt like others had my back here. Marlboro has flexibility, independence and a sense of community. It really speaks to me.”

Sara Salimbeni, Marlboro’s new physics professor and a native of Rome, Italy, enjoys introducing students to some of the deepest mysteries of the universe. But she did not always know she would be an astronomer.

Sara Salimbeni, Marlboro’s new physics professor and a native of Rome, Italy, enjoys introducing students to some of the deepest mysteries of the universe. But she did not always know she would be an astronomer.

“When I was a child I wanted to be a painter,” Sara jests. “It didn’t work out.” Sara received her laurea in physics from the University of Rome, La Sapienza, and her doctorate in astronomy from the University of Rome, Tor Vergata. Her dissertation, “Cosmological evolution of galaxies from deep multicolor surveys,” examines how different galaxies have changed over billions of years.

“We have these wonderful pictures from the Hubble Space telescope, or telescopes in Chile and other parts of the world, from which we are able to understand many things that occur at different times,” Sara declares. “The light travels with a speed that is not infinite, so it takes time to get to earth. The farther away the galaxy you are watching, the more you are looking into the past.”