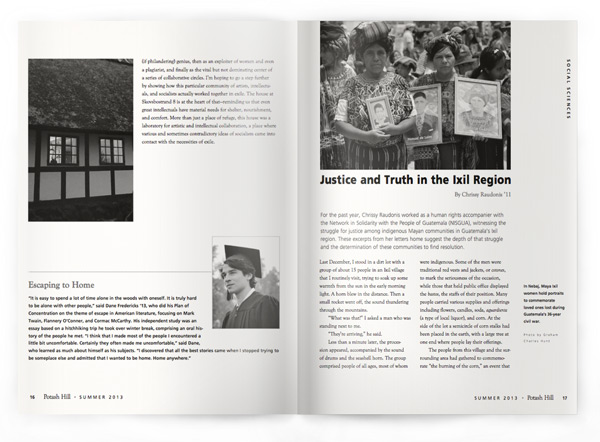

By Chrissy Raudonis ’11

For the past year, Chrissy Raudonis worked as a human rights accompanier with the Network in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala (NISGUA), witnessing the struggle for justice among indigenous Mayan communities in Guatemala’s Ixil region. These excerpts from her letters home suggest the depth of that struggle and the determination of these communities to find resolution.

Last December, I stood in a dirt lot with a group of about 15 people in an Ixil village that I routinely visit, trying to soak up some warmth from the sun in the early morning light. A horn blew in the distance. Then a small rocket went off, the sound thundering through the mountains.

Last December, I stood in a dirt lot with a group of about 15 people in an Ixil village that I routinely visit, trying to soak up some warmth from the sun in the early morning light. A horn blew in the distance. Then a small rocket went off, the sound thundering through the mountains.

“What was that?” I asked a man who was standing next to me.

“They’re arriving,” he said.

Less than a minute later, the procession appeared, accompanied by the sound of drums and the seashell horn. The group comprised people of all ages, most of whom were indigenous. Some of the men wore traditional red vests and jackets, or cotones, to mark the seriousness of the occasion, while those that held public office displayed the bastos, the staffs of their position. Many people carried various supplies and offerings including flowers, candles, soda, aguardiente (a type of local liquor), and corn. At the side of the lot a semicircle of corn stalks had been placed in the earth, with a large tree at one end where people lay their offerings.

The people from this village and the surrounding area had gathered to commemorate “the burning of the corn,” an event that occurred during Guatemala’s decades of internal armed conflict. One day in 1982, the army arrived with several hundred Ixil Self-Defense Civil Patrol (PAC) members, with orders to gather all of the corn that was drying in the fields awaiting the harvest. The army explained to the PAC members that they were going to distribute the corn to the communities. The PAC members spent the day gathering all the corn in the area, including part of the harvest of several other villages, and dumping it in the lot, forming a gigantic pile.

When the work was done, instead of distributing the food, the soldiers burned the whole heap, throwing the villagers’ clothes on top, including the women’s traditional, handmade huipiles and red cortes: their shirts and skirts. Witnesses from a village in the valley below, miles away, were able to see the giant “volcano of corn.” Sadly, the harvest was not the only loss of the day. The soldiers also threw several people on the fire alive, including a blind, elderly woman. The loss of life, and of the harvest, was devastating for the close-knit community of subsistence farmers for whom corn is sacred. Culturally, the burning of the corn was an unthinkable act.

To remember the past and beg forgiveness for the destruction of the harvest, Mayan priests lit a ceremonial fire. Participants watched and prayed toward the four directions. The air was full of the fragrance of smoke, the sound of the drums and chirmiria (a wind instrument), and occasional rockets, whose white tails marked the cloudless, blue sky. At one point, a man approached my partner and me. In the palm of his hand were the charred remains of corn kernels that he had found by digging a little in the dirt. It was powerful to witness the physical remains of the event, still present in the ground, decades later.

During Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war, which ended in 1996, this region was called the “Ixil Triangle” by the military. It was the site of severe civilian repression and control through military checkpoints, the concentration of populations in model villages, and coerced inscription in armed civilian patrol groups. The conflict resulted in the massacres of civilians by the army and the displacement of entire communities.

During Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war, which ended in 1996, this region was called the “Ixil Triangle” by the military. It was the site of severe civilian repression and control through military checkpoints, the concentration of populations in model villages, and coerced inscription in armed civilian patrol groups. The conflict resulted in the massacres of civilians by the army and the displacement of entire communities.

My work in the region is greatly tied to this history, although the specifics of my day-to-day activities vary. Some days I spend in different communities, visiting witnesses in genocide cases. While accompaniment work hopes to dissuade attacks and threats against those who are accompanied, there is also a strong element of solidarity in my interactions with many of the people that I visit. I talk with villagers about their children, their crops, and the local community to try to show that they are not alone in the huge and confusing process that is the search for justice and truth in Guatemala. Other days I spend accompanying meetings with witnesses and the organizations that represent them and with groups that are fighting to keep the control of land and natural resources in the hands of the local communities.

My first visit to a community showed me how the conflict has influenced people’s perspectives and how the logic of resistance and survival is very different from what I’m accustomed to. This particular community is small and fairly isolated—three hours by bus from the the closest town with police and government offices. The village has no electricity or running water. A single, wide dirt road connects it to other towns.

My first visit to a community showed me how the conflict has influenced people’s perspectives and how the logic of resistance and survival is very different from what I’m accustomed to. This particular community is small and fairly isolated—three hours by bus from the the closest town with police and government offices. The village has no electricity or running water. A single, wide dirt road connects it to other towns.

During the evening, I was sitting in a wooden chair next to a cook fire in the house I was staying in, drinking coffee with my partner and the woman who was hosting us. At one point, the woman started to talk about the war and mentioned some of the violence and hardships that the townspeople suffered. She briefly told us about the soldiers coming to the town and killing villagers. But what she wanted to talk about was her worry that it would happen again. She pointed toward the road and explained that this road would make it easy for the army to come back anytime it wanted to. As my partner tried to reassure her as best she could, I found myself considering a whole different perspective.

A lot of people that I’ve met in Guatemala have talked about the need for more development and less isolated villages. This was my first time hearing the concern that being connected and accessible would also make the population more vulnerable. Something as simple as a dirt road can be a source of worry, especially for those who are still traumatized by their war experiences.

Unfortunately, such worries are not unfounded. The country is becoming increasingly militarized in some areas, with the stated purpose of fighting drug trafficking. However, in most cases the militarized areas are also rich in natural resources, and many people see the increase in military outposts and bases as a means of providing economic security to investors rather than protecting the nation. The state of siege imposed on the town of Barillas last May and the massacre of seven peaceful protesters by soldiers in Totonicapan in October show that the government is also disposed to use its military power to control the civilian population.

Although most of the land in the Ixil region has relatively low agricultural potential, the area’s mineral wealth and abundance of rivers make it a popular site for mining and hydroelectric projects. Conflicts over land and natural resources are widespread through the region and often affect my work as an accompanier.

Although most of the land in the Ixil region has relatively low agricultural potential, the area’s mineral wealth and abundance of rivers make it a popular site for mining and hydroelectric projects. Conflicts over land and natural resources are widespread through the region and often affect my work as an accompanier.

For example, one community that I visit sits high up in the mountains, just under a forested ridgeline. From the road that goes through the town, I can look out over the valley below, bounded by a parallel ridge. The vista is patterned with cornfields, forests, and towns that are connected by winding dirt roads. The village is picturesque, with its expansive green fields full of grazing sheep backdropped by distant mountains, but I keep my camera in my bag. The tranquil-seeming setting is of great interest to a Mexican oil company that hopes to extract barite, an important mineral in the oil drilling process.

When my partner and I leave the community, we go by the main road, even though we know that there is a shorter and reportedly very pretty path that can also take us to our next destination. As outsiders, we have to tread with caution, because local residents are highly concerned about company employees entering their territory. One man from the area explained to me that the community isn’t against development in and of itself. They want development, but a development that comes from within the community and benefits the community. While this village has managed to keep land ownership in the hands of local residents, others are less fortunate and find themselves with less leverage against the interlocked interests of corporations and the national government.

The process of losing local control over land is closely tied to the internal armed conflict. In 1984, in the middle of the violence, the government nationalized over 3,800 acres of land in one town, without notifying the local population. It wasn’t until a few years ago that the community discovered they were no longer the owners of their communal land, or ejido, when a government employee let the information slip.

During June and July, my partner and I accompanied meetings convened by a collective called Resistencia de los Pueblos (Resistance of the People), which were intended to inform villagers about what had happened to their land and the future plans of mining and hydroelectric companies in the area. Land security and environmental quality are of the utmost importance to the local people, who depend on subsistence agriculture for a large part of their livelihood. As one member of the collective explained to a group, “It’s a sin to not defend the land, because without land we don’t have life.”

Chrissy Raudonis graduated from the World Studies Program with a Plan of Concentration in environmental studies and Spanish, focusing on social and environmental issues around mining in Latin America. After accompanying Ixil witnesses and their supporters involved in the ongoing case for genocide against former general José Efraín Ríos Montt, she returned to the U.S. in May.

Roots of Genocide

“One of the primary complications of studying genocide, and what precedes it, is that the process is not linear or easily reductive,” said Taylor Burrows ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the social and political roots of genocide. Faced with the challenges of complicated and interrelated social, political, and historical factors, Taylor teased out elements that she felt most directly contributed to systemic violence in Bosnia and Rwanda. She considers it good news that no single factor launches a path to genocide, offering many junctures for intervention. “As many scholars have reminded us, genocide is a relatively rare occurrence, despite the overwhelming number of ethnically, politically, and nationally diverse states,” said Taylor. “Even within the realm of ethnic conflict, systemic violence is rarely the outcome.”

“One of the primary complications of studying genocide, and what precedes it, is that the process is not linear or easily reductive,” said Taylor Burrows ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the social and political roots of genocide. Faced with the challenges of complicated and interrelated social, political, and historical factors, Taylor teased out elements that she felt most directly contributed to systemic violence in Bosnia and Rwanda. She considers it good news that no single factor launches a path to genocide, offering many junctures for intervention. “As many scholars have reminded us, genocide is a relatively rare occurrence, despite the overwhelming number of ethnically, politically, and nationally diverse states,” said Taylor. “Even within the realm of ethnic conflict, systemic violence is rarely the outcome.”