By Kyhl Lyndgaard

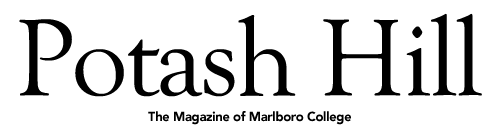

Writing professor Kyhl Lyndgaard finds that 19th-century attitudes about “Indian removal” were echoed by a notable shift in the common names of native orchids.

One year before the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Almira Lincoln Phelps published the first edition of her Familiar Lectures of Botany. Phelps wrote that “the Orchis tribe” are “opposing all attempts at civilization, [and] are to be found only in the depths of the forest…. we may, in this respect, compare them to the aboriginal inhabitants of America, who seem to prefer their own native wilds to the refinements and luxuries of civilized life.” Many species of native orchids were commonly called moccasin flowers at the beginning of the 19th century. Yet by 1900, the usual term was the same as that used in England: the lady’s slipper. This shift in plant names ominously mirrors social perceptions of the apparent need for Indian removal during the same period.

The ways white Americans wrote about moccasin flowers during the 19th century—and the ways this earlier name slowly fell from common usage—illustrate how Indian removal was rationalized based on changes in the landscape. The moccasin flower was routinely used as a symbol representing Native Americans in discourse on federal policies of Indian removal. This selective use of botanical information allowed political sentiment about Indian removal to have an undue factual basis in nature study, and often led to the unwitting complicity of progressive writers.

William Cullen Bryant used his editorship at the New-York Evening Post as a platform to editorialize in support of parks and conservation, but nonetheless supported President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Bryant’s poetry often draws upon flowers, including the moccasin flower, to symbolize not only death in general, but also the inevitable extinction of Native American culture. In “The Maiden’s Sorrow” (1842), Bryant writes,

Far on the prairies of the west,

Far on the prairies of the west,

None who loved thee beheld thee die;

They who heaped the earth on thy breast

Turned from the spot without a sigh.

There, I think, on that lonely grave,

Violets spring in the soft May shower;

There, in the summer breezes wave

Crimson phlox and moccasin flower.

Bryant’s poetry suggests that Native Americans are already relegated to exile. His contemporary audience readily understood the many contemporary references and social attitudes in his writing.

In a later example, Susan Fenimore Cooper made a valuable comparison between weeds and native flowers in Rural Hours (1850):

The wild natives of the woods grow there willingly, while many strangers, brought originally from over the Ocean, steal gradually onward from the tilled fields and gardens, until at last they stand side by side upon the same bank, the European weed and the wild native flower.

These foreign intruders are a bold and hardy race, driving away the prettier natives. It is frequently remarked by elderly persons familiar with the country, that our own wild flowers are very much less common than they were forty years since…. The moccasin-flower abounded formerly even within the present limits of the village.

Cooper opens this passage by linking disturbed ground to the ability of weeds to take hold where native plants formerly made up the entire population. She specifies that the weeds are European, and constitute a “bold and hardy race” that continues to displace the native population. Cooper claims that this is a “mingled society” in which examples of both European and North American origins can potentially “stand side by side.” The inevitability of Indian removal is not a foregone conclusion for her, despite the elegiac nature of her father’s novel Last of the Mohicans.

Fascinating corollaries were developed in response to the increasing scarcity of native orchids as the 19th century progressed. Some argued that the moccasin flower could be domesticated, a claim connected to the opening of the first Indian boarding schools. Laura Sanford explained in an 1891 horticultural article that “if we are to possess the representatives of this fair and fascinating race, which belong to us as the native offspring of American soil, we must guard them from destruction in their favorite haunts.” Words such as “possess” support assimilation as a perceived necessity. Sanford also expresses a newly found romantic pride in America’s native populations. Her article is conspicuously devoid of words identifying the subject as a plant and could be mistaken for the words of progressive reformers. Sanford ultimately asserts that the moccasin flower dies from “homesickness” after a year or two. As seen by death rates upon removal to reservations or boarding schools, Native Americans also suffered terribly upon the loss of their homes.

Still, this argument found favor with writers who were sympathetic to Native Americans and reluctantly felt that assimilation was the best hope for ensuring human rights. Lydia Maria Child contrasted wildflowers with domestic plants to grapple with questions of Indian removal. Her short story “Willie Wharton” examines the life of a boy who was taken captive by Indians and returned later in life to his biological family with a Native American bride. His well-meaning family, while they give space to the couple to assimilate, compare plants to ethnic groups. Child writes that “the wild-flowers of the prairie were supplanted by luxuriant fields of wheat and rye,” while the character Uncle George remarks that Willie’s native bride is as “‘bright as the torch-flower of the prairies’” and that “‘wild-flowers, as well as garden-flowers, grow best in the sunshine.’” Child—and many other progressive and transcendentalist writers—promoted assimilation through flower analogies.

Elaine Goodale Eastman’s 52-line poem “Moccasin Flower” includes lines pointing to a more nuanced relationship among whites, Native Americans and native orchids:

Elaine Goodale Eastman’s 52-line poem “Moccasin Flower” includes lines pointing to a more nuanced relationship among whites, Native Americans and native orchids:

Yet shy and proud among the forest flowers,

In maiden solitude,

Is one whose charm is never wholly ours,

Nor yielded to our mood:

One true-born blossom, native to our skies,

We dare not claim as kin,

Nor frankly seek, for all that in it lies,

The Indian’s moccasin.

Eastman describes in code the tension between North American inhabitants at the time. Published in the well-received poetry collection In Berkshire with the Wildflowers (1879) when Eastman was only 16, the poem clearly articulates the resistance of the “native,” rather than relying upon the more common theme of vanishing. At this point in the poem Eastman pivots slightly, spending the next 10 lines on the difficulties of finding the moccasin flower. She ends the poem on a strange note:

With careless joy we thread the woodland ways

And reach her broad domain.

Thro’ sense of strength and beauty, free as air,

We feel our savage kin,—

And thus alone with conscious meaning wear

The Indian’s moccasin!

In these final lines of the poem, Eastman places the writer—and reader—in the shoes of Native Americans. The “careless” quality of the poem’s joy suggests an irresponsible hope to escape civilization. After first claiming the moccasin flower is off-limits, Eastman is strangely unable to stop herself from completing the journey. Her own life followed a fascinating parallel with this poem: she taught Native American children in South Dakota, marrying Charles Eastman shortly after assisting him in nursing the victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Elaine likely made significant contributions to Charles’ books, which include Indian Boyhood.

Writing at the end of the 19th century, Mabel Osgood Wright expressed regret over these changes to the land and its native inhabitants: “Ladies’ Slipper is not a word in keeping with Hemlock and Beech woods, but the word Moccasin throws meaning into the black shadows and brings to mind the stone axe and flint arrow-heads found not long ago.” When Wright spies a moccasin flower along a roadside, she picks it, but only because of worries that someone else will see it and “follow the trail into the woods, and make the whole colony prisoners.” While Wright’s knowledge of Native American culture is somewhat superficial, she is insistent on the importance of local knowledge. Wright argues to keep the name moccasin flower, stating that when “a common name, spicy with the odor of the new western world, is given to a plant, I think we should keep it…and call our little group of inflated pouched Orchids, Moccasin Flowers, instead of Ladies’ Slippers, as Britton does, a general title which confuses their personalities with the European species.” However, her argument is belated, as the common name of lady’s slipper had by then all but supplanted the earlier usage of moccasin flower.

Despite persisting worries about captivity on the frontier, by the end of the 19th century native orchids with slipper-shaped pouches were commonly called lady’s slippers, rather than moccasin flowers. The removal of Native Americans from lands that white settlers desired—especially those east of the Mississippi, which correspond with the primary natural range of these orchids—was all but complete. Nonetheless, a more positive parallel may be made today: Native Americans were and are still very much present, as are many species of moccasin flowers, despite relentless attempts to destroy, displace and domesticate. A final example that explains why using moccasin flowers as a symbol for Native Americans was a problem can be plucked from Child’s prologue to “Willie Wharton.” She writes: “Would you like to read a story which is true, and yet not true? The one I am going to tell you is a superstructure of imagination on a basis of facts.”

Kyhl Lyndgaard teaches writing at Marlboro, with a focus on environmental studies and literature. He is working on an anthology of essays, fiction and poetry tentatively entitled Currents of the Universal Being: Explorations in the Literature of Energy.

The essence of orchids

While orchids symbolize changing attitudes for Kyhl, they quite literally changed the life and livelihood of Don Dennis ’82. After moving to England and trying a sustainable timber business, Don began importing flower essences for healing purposes. “One of our early suppliers was a woman in California who was making essences with orchids grown in her greenhouse,” said Don, who now lives in Scotland and is the author of Orchid Essence Healing. “Like T. Wilson with poetry, or Audrey Gorton with Shakespeare, this woman communicated a tremendous passion for her subject: it was then that orchids caught my notice for the first time.” Don bought his first small orchid (a Phragmipedium hanne popow), and this led to a second, and soon he had to build a greenhouse to house them all. Visit www.healingorchids.com to learn more. Photo: Fruits of love orchid, by Don Dennis

While orchids symbolize changing attitudes for Kyhl, they quite literally changed the life and livelihood of Don Dennis ’82. After moving to England and trying a sustainable timber business, Don began importing flower essences for healing purposes. “One of our early suppliers was a woman in California who was making essences with orchids grown in her greenhouse,” said Don, who now lives in Scotland and is the author of Orchid Essence Healing. “Like T. Wilson with poetry, or Audrey Gorton with Shakespeare, this woman communicated a tremendous passion for her subject: it was then that orchids caught my notice for the first time.” Don bought his first small orchid (a Phragmipedium hanne popow), and this led to a second, and soon he had to build a greenhouse to house them all. Visit www.healingorchids.com to learn more. Photo: Fruits of love orchid, by Don Dennis