Summer 2011

Editor’s Note

“For the many students who do interdisciplinary Plans, it’s the dialogue that’s important,” said theater professor Paul Nelsen at an open forum about the recent SymBiotic Art and Science conference. Paul explains that whether two disciplines collide or interact may depend as much upon the student as on the different fields involved, but it always creates an interesting dialogue. Ultimately it broadens our lives and has a humanistic impact beyond the studies themselves.

Interdisciplinary exploration is a well-practiced approach at Marlboro, as you can see from many of the Plans of Concentration listed in the commencement section of this issue of Potash Hill. Like all academic endeavors, that work never stops as we explore new and deeper connections between apparently separate perspectives. This issue celebrates Marlboro’s interdisciplinary tradition, whether it’s between philosophy and economics in Isaac Lawrence’s article on the Vermont Land Trust, or literature and international development in Rosario de Swanson’s piece on Guinean writers. It also explores new horizons in the SymBiotic Art and Science conference mentioned above and the Embodied Learning Symposium hosted here on campus.

As always, we welcome your comments. How has interdisciplinary study made an impact on your life and career, and what exciting new syntheses are out there to explore? You can find responses to the last issue in Letters.

—Philip Johansson, editor

Front cover: “La Mer,” a freehand paper cut on recycled paper by Paige E. Martin ’11, from her Plan exhibition titled “When Pictures Speak.” Photo by Jeff Woodward

Table of Contents

Restoring Kona Forests

by Robert Cabin ’89

Restoration ecology has been called the “acid test” of ecological sciences: If we really understand how ecosystems function, we should be able to put them back together again. Bob Cabin is rising to that challenge in the devastated dry forests of Hawaii.

I could see the charred remains of the ghost forest from the highway. One mile below me, the dead trees rose up from the land like giant skeletons. There were many reasons not to walk down there: the steep slope, the intense heat, the dense swath of neck-high African fountain grass I would have to fight my way through to reach the ruined trees. Even worse, I’d worked as a restoration ecologist in Hawaii long enough to visualize the devastation I was going to see when I got there. But a glimmer of hope for this ecological wreckage also compelled me to go, so I stepped off the highway and into a sea of dead grass, toward the barren lava flow and the burnt forest beyond.

The lowland, dry, leeward sides of all the main Hawaiian Islands were once covered by vast, magnificent forests teeming with strange and beautiful species found nowhere else on earth. Tens of thousands of brightly colored, fungi-eating snails slithered through the trees and inched their way along the dark underlying leaf litter. Vast flocks of giant flightless geese squawked across the forest understories; dozens of species of finch-like honeycreepers sipped nectar, gobbled insects and sought shelter from the heat and hungry eagles, hawks and owls.

The Hawaiians loved these forests and often chose to live in or near them. Due to the hot and dry climate, many of the trees grew extremely slowly and produced some of the hardest woods in the world, which the Hawaiians fashioned into buildings, tools, weapons and musical instruments. They also made exquisite, multicolored capes containing hundreds of thousands of bird feathers, and strung elaborate leis out of vines and sweet-smelling flowers. The first time I walked through a patch of native dry forest containing a grove of alahee trees in full bloom, I told my native Hawaiian colleague that the light fragrance of their delicate white flowers seemed to creep mysteriously in and out of my nostrils. He smiled and explained that the Hawaiian word alahee literally means “to move through the forest like an octopus.”

Today we can only imagine what these complex ecosystems looked like and guess at how they worked. Tragically, about 95 percent of Hawaii’s original dry forests have been destroyed, and many of their most ecologically important species are functionally, or actually, extinct. For example, most of the native birds and insects that once performed such critical services as flower pollination and seed scarification and dispersal are now gone. Many of the once dominant and culturally important canopy trees are also extinct or exist in only a few small populations of scattered and senescent individuals.

Today we can only imagine what these complex ecosystems looked like and guess at how they worked. Tragically, about 95 percent of Hawaii’s original dry forests have been destroyed, and many of their most ecologically important species are functionally, or actually, extinct. For example, most of the native birds and insects that once performed such critical services as flower pollination and seed scarification and dispersal are now gone. Many of the once dominant and culturally important canopy trees are also extinct or exist in only a few small populations of scattered and senescent individuals.

The demise of Hawaii’s dry forests began soon after the Polynesian discovery of these islands around 400 A.D. Like indigenous people throughout the tropics, the early Hawaiians cleared and burned the dry coastal forests and converted them into cultivated grasslands, agricultural plantations and thickly settled villages. Captain James Cook’s arrival in 1778 set in motion a chain of events that dramatically accelerated the scope and intensity of habitat destruction and species extinctions throughout the Hawaiian Islands. While the Polynesians had deliberately brought many new species to Hawaii in their double-hulled sailing canoes (and some stowaways such as the Polynesian rat, geckos, skinks and various weeds), their impact was trivial compared to the ecological bombs dropped by the Europeans. Thinking the islands deprived of some of God’s most useful and important species, Cook and his successors, with the best of intentions, set free cows, sheep, deer, goats, horses and pigs. Over time, foreigners from around the world unleashed a veritable Pandora’s box of more ecological wrecking machines, including two more species of rats, mongooses (in an infamously ill-advised attempt to control the rats), mosquitoes, ants and a diverse collection of noxious weeds. These included the African fountain grass that scratched my bare arms and legs as I struggled to reach the burnt forest.

During relatively rainy periods, when fountain grass greens up and is in full bloom, large swaths of the leeward side of the Big Island can look like a lush Midwestern prairie. But inevitably, the merciless kona (leeward) sunshine returns, and the rains disappear for months on end. The fountain grass dries to a sickly brown; then all it takes is somebody to park their hot car over a clump of grass for the whole region to burst into flame like a barn full of dry hay. In contrast to most Hawaiian species, fountain grass originated within a savanna ecosystem that regularly burned, and consequently has had thousands of years to evolve mechanisms to cope with and even exploit large-scale fires. I have watched fountain grass rise up from its ashes like a green phoenix after several seemingly devastating wildfires: Vigorous new shoots quickly appear within the old burned clumps, seeds germinate en masse and the emerging seedlings rapidly establish within the favorable post-fire environment of increased light and nutrients and decreased plant competition.

The net result of these fires is thus more fountain grass and less native dry forest. More grass means that during the next drought there will be even greater fuel loads, which in turn leads to more frequent and widespread fires. This growing cycle of alien grass and fire has proven to be the nail in the coffin for dry forests on the Big Island and throughout the tropics as a whole. The reason we don’t hear about campaigns to save tropical dry forests is because there are now virtually no such forests left to save. If we want at least some semblance of this ecosystem to exist in the future, we’ll have to deliberately and painstakingly design, plant, grow and care for them ourselves.

The net result of these fires is thus more fountain grass and less native dry forest. More grass means that during the next drought there will be even greater fuel loads, which in turn leads to more frequent and widespread fires. This growing cycle of alien grass and fire has proven to be the nail in the coffin for dry forests on the Big Island and throughout the tropics as a whole. The reason we don’t hear about campaigns to save tropical dry forests is because there are now virtually no such forests left to save. If we want at least some semblance of this ecosystem to exist in the future, we’ll have to deliberately and painstakingly design, plant, grow and care for them ourselves.

As I approached the dead trees, I was hot and frustrated that I had not even seen this forest before it burned. Yet in a bittersweet way I was glad that I had never been there, because even without any personal connection to this place, the sight of those wrecked trees was almost unbearably depressing. This had apparently been one of the best native dry forest remnants left within the entire state, but now we would never know which species had lived here, and we would never be able to collect seeds or cuttings from its gnarled old trees that were now on the very edge of extinction.

I looked back upslope at our tiny parcels of native trees straddling the highway. To preserve and restore these forest remnants, our Dryland Forest Working Group collectively spent thousands of hours installing fire breaks, killing fountain grass and exotic rodents, collecting seeds, and propagating and transplanting thousands of native plants. Local groups ranging from troubled Hawaiian teenagers to real estate agents had repeatedly donated their time and labor to help with these efforts. Hundreds of people within and beyond the Hawaiian Islands had come to see and study this ecosystem. My own scientific research program had progressed from documenting the demise of these forests to experimenting with promising techniques for restoring them at ever-larger spatial scales.

I looked back upslope at our tiny parcels of native trees straddling the highway. To preserve and restore these forest remnants, our Dryland Forest Working Group collectively spent thousands of hours installing fire breaks, killing fountain grass and exotic rodents, collecting seeds, and propagating and transplanting thousands of native plants. Local groups ranging from troubled Hawaiian teenagers to real estate agents had repeatedly donated their time and labor to help with these efforts. Hundreds of people within and beyond the Hawaiian Islands had come to see and study this ecosystem. My own scientific research program had progressed from documenting the demise of these forests to experimenting with promising techniques for restoring them at ever-larger spatial scales.

Looking at the fruits of our work from this distance, I felt a wave of optimism sweep over me, and for the first time truly believed that even this saddest of all the sad Hawaiian ecosystems could be saved. I turned around again and looked at the scorched trees. “We can grow another forest here,” I muttered. “We know what to do, and how to do it.” I stomped on a clump of resprouting fountain grass, slung on my pack and marched back up to the highway to get to work.

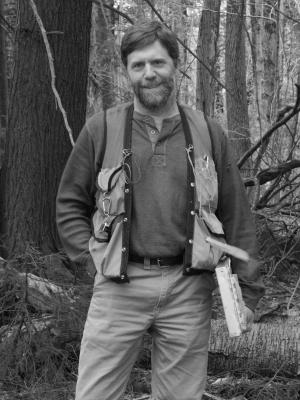

Robert Cabin is an associate professor of ecology and environmental science at Brevard College. This article is adapted from his book Intelligent Tinkering: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Practice, which will be published by Island Press this summer (ISBN: 9781597269643). You can read Bob’s views on environmental issues in his Huffington Post blog.

Phylogenetic Tree: The Evolutionary Legacy of Bob Engel

Bob Cabin is one of the many former biology students of retired Marlboro professor Bob Engel who has gone on to make his own mark in the world of life sciences. He said, “Bob was the first professor I ever had that really challenged me, the first to befriend me in a real, substantive way and the first to tease me mercilessly.” Although the elder professor Bob would rather that we observed his retirement with a simple, “He rode his motorcycle off into the sunset,” that would hardly do for many Potash Hill readers. Instead, we rounded up a small sampling of Bob’s “academic genealogy” to share a bit about their own careers and Bob’s impact on their trajectories.

Tom Good ’86 received his Ph.D. from the University of Kansas, where he studied hybridization in seabirds along the Pacific coast. Since 2001 he has been a research biologist at the National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA Fisheries lab in Seattle, Washington, where he conducts research on seabird-fisheries interactions (see Potash Hill Winter–Spring 2007). “I had started at Marlboro with the idea of fashioning a Plan on education, but after taking an introductory biology class with Bob, I was hooked on the subject. Additional classes followed, and I knew then that my life would revolve around biology and ecology. In fact, much of my present research traces all the way back to Bob’s tutelage at Marlboro. I admired his knowledge of the natural world (broader than anyone I have ever met) and his tireless devotion to teaching in the field.”

After leaving Marlboro, Hall Cushman ’82 received his M.S. in ecology and evolutionary biology from the University of Arizona and his doctorate in biology from Northern Arizona University in 1989. He is now a professor of biology at Sonoma State University in northern California, where he has been teaching and conducting research on population and community ecology since 1994. “Bob’s influence on my life and professional trajectory was, and still is, nothing short of profound. To this day, I vividly remember meeting him in 1978 when, during an epic snowstorm, I visited Marlboro as a prospective student. I was considering multiple colleges and majors at the time but, after this meeting, decided to attend Marlboro, study biology and work closely with Bob. This decision is one that I have never regretted—I am still devoted to Marlboro, biology, teaching and research.”

Post-Marlboro, Tracey Devlin ’82 earned a master’s degree in science education and taught biology and physical science at the high school level and at Landmark College. Along with Dan Toomey ’79, she subsequently started Marlboro’s Learning Resources Center (now Academic Support Services), which offered assistance with learning and teaching skills and strategies to students and faculty. For the past several years, Tracey has been a private tutor and stay-at-home mom. “During our first field trip for Plants of Vermont, we stood shrouded in dense fog on the top of Mount Mansfield listening to Bob expound upon the adaptive strategies of some tiny arctic plant while the wind whipped around us. It was so cold that one student had Bob’s toy poodle zipped inside his jacket so she wouldn’t get hypothermia, while others were wearing spare socks on their hands. I thought, ‘This is dedication.’”

Norman Paradis ’79 earned his M.D. from Northwestern University Medical School and went on to practice and teach emergency medicine at universities across the country, most recently at the University of Southern California. No longer working full time at the university, Norman now works as a part-time chief medical officer for biotech start-ups. “Since leaving Marlboro, I have spent much of my professional life in a dialogue with colleagues and students on the complexity and beauty of living systems. After all of those now innumerable conversations, Bob still stands out. No one has made me feel more powerfully that life on our planet is, when all is said and done, amazing. And I have chosen that word specifically for its unscientific connotation, for when Bob gets going and is in full didactic plumage, the vision is not simply empirical but, in the end, miraculous.”

Lara Knudsen ’03 received her M.D. as well as a master’s degree in public health from George Washington University in 2008, after extensive international experience working on women’s health in Uganda and Peru. She is currently finishing up a residency in family medicine and in August plans to move back home to Oregon (with her husband, Chris Jones ’05). “Biology class with Bob was fascinating because he would open each class with the question, ‘Well, what are you curious about?’ And we could ask him anything—why do leaves change colors, why do birds have different calls, what are the parasites I brought back from India? He was always game for any random biology question, and in fact seemed to center his class around them. Bob helped me establish a habit of being naturally curious about things, which leads to endless learning—a valuable asset in the field of medicine.”

Having worked on conservation in the desert southwest since he left Marlboro, Tim Tibbitts ’80 is now a wildlife biologist at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona. There he manages programs for endangered species, wildlife management, visiting researchers and other activities. Tim led efforts to restore Quitobaquito Pond, saving the endemic Quitobaquito pupfish and Sonoyta mud turtles from extinction. “Bob introduced me to Quitobaquito on a Marlboro field trip in 1979, so I’ve thought fondly of him during many days of working out there in the dust, mud, bulrush, stinging waterbugs, Africanized honeybees and 110-degree heat. I came from a rough, rural public high school, and Bob taught me to learn, think and grow better. His passion for and knowledge of biology was highly contagious. My vocation has been an attempted 30-year extension of Bob’s desert biology field course, minus the wild nights at the Bum Steer in Tucson.”

After graduating from the University of Arizona in 1999 with a B.S. in nursing, Cristina Wigert ’92 worked at the University Medical Center in an intensive care “step down” unit, dealing with trauma and transplant patients. She went on to work at several other hospitals in Tucson before recently moving back to New England. “My physiology tutorials with Bob were probably better than any I could have gotten at a large university, allowing me to jump right into a nursing program and providing me with the knowledge I need on a daily basis. I have very happy memories of my tutorials in Bob’s little corner office, the one infested with cockroaches and always smelling a bit like a swamp. I would settle into his beat-up old chair for a stimulating hour’s discussion on the evolution of air-breathing in lungfish. Those were good times.”

Peter Newiarowski ’84 went on to get his doctorate in ecology and evolution from the University of Pennsylvania and conducts research on the physiology and ecology of lizards and salamanders. He has taught biology at the University of Akron since 1995, and in 2009 was made the interim director of Integrated Bioscience, a doctoral program he helped develop. “Bob made me want to be a biologist, and that came out of nowhere. Bob’s teaching was transformative like that for many students. Leading by example, he encouraged and guided his students to be creative, analytical, playful and passionate. Bob is the most gifted teacher I have ever encountered or probably ever will. I fondly remember his frequently foul-mouthed bird muttering expletives in his office, the trance he would seem to go into when watering plants in the greenhouse and his insane and irrational love of the VW microbus.”

Bob’s colleague at Marlboro for 22 years and counting, Jenny Ramstetter ’81 said, “Bob helped me shape my childhood love of nature into a life of studying plants and teaching.” Jenny is pleased to announce a new award to celebrate Bob’s extraordinary gifts as a teacher, naturalist and friend to so many Marlboro students. “Although Bob is retiring, I know he will continue to inspire students and those in other walks of life: residents of a local nursing home, fellow motorcyclists, my own young children and more. We offer the new Robert E. Engel Award to the next generation of naturalists from Marlboro College.”

How to convert this country into a paradise

Cómo convertir este país en un paraíso

by Rosario de Swanson

Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson traveled to Equatorial Guinea last year to talk with Guinean writers about their difficult history and the emerging role of literature in a more hopeful future.

“Throughout Equatorial Guinea, from the very date of independence, we experienced a lack of freedom and a shortage of food that was impressive,” said writer Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel. “But as the things we lacked were things many of us had never had, we did not realize we did not have them. And as the administration was almost nonexistent, it was normal that education was merely testimonial. It’s almost a miracle that a single writer could come out of Guinea from that time.” Ávila Laurel is living proof that such a miracle has occurred, and he is just one of a large group of emerging writers from the only African nation where Spanish is spoken.

My interest in Guinean literature and culture is closely connected to the themes I explored in my dissertation: the emergence of Afro-Hispanic American literature in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru and the causes that delayed its recognition until well into the 20th century. I was surprised to learn that there was an African literature written in Spanish, with themes similar to those found in Latin American literature, that many of us Latinoamericanistas did not know about. The study of this rich literature and culture is important because it challenges established literary borders, as Guinean writers frequently reference not only Africa and Spain but also Latin America. In March 2010, I traveled to Equatorial Guinea to interview Ávila Laurel, part of the first postcolonial generation of writers there, and to talk with other writers whose works form the nueva literatura Guineana.

Equatorial Guinea’s inequalities are rooted in the colonial past and exacerbated by a globalized present. Located in central Africa, between Gabon and Cameroon in the Gulf of Guinea, this tiny territory was a distant outpost that served primarily to assert Spain’s former imperial power after losing its American colonies in 1898—and for the extraction of human and natural resources. As a late colony of Spain (1778–1968), the historical trajectory of Equatorial Guinea is markedly different from that of Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as from that of other African countries. Yet the Latin American experience informed the Spanish colonial enterprise in Africa.

The literature of Equatorial Guinea was born in the crucible of two great traditions: Afro-Bantu oral traditions and the written forms of Hispanic traditions. The birth of Guinean literature, different from the colonial perspective of Africanismo literario, can be traced back to the missionary newspaper La Guinea Española. In 1947 the newspaper opened a section to black Guineans entitled “Historias y Cuentos.” This section published the works of the native literati, who were invariably male students and teachers of the missions and seminaries, and opened a space for reflection about the place Guinean culture occupied within the Spanish and Latin American cultural and linguistic spectrum. It was here that the first transcriptions of Guinean oral traditions from the different ethnic groups (Fang, Ndowe, Bubi, Bissio) began to undergo a process of reinterpretation and synthesis.

The literature of Equatorial Guinea was born in the crucible of two great traditions: Afro-Bantu oral traditions and the written forms of Hispanic traditions. The birth of Guinean literature, different from the colonial perspective of Africanismo literario, can be traced back to the missionary newspaper La Guinea Española. In 1947 the newspaper opened a section to black Guineans entitled “Historias y Cuentos.” This section published the works of the native literati, who were invariably male students and teachers of the missions and seminaries, and opened a space for reflection about the place Guinean culture occupied within the Spanish and Latin American cultural and linguistic spectrum. It was here that the first transcriptions of Guinean oral traditions from the different ethnic groups (Fang, Ndowe, Bubi, Bissio) began to undergo a process of reinterpretation and synthesis.

Leoncio Evita Enoy, widely considered the father of Guinean literature, wrestled with the fact of colonization in his work. He was among the first writers who moved away from a mere retelling of myths and legends to an in-depth interpretation of Guinean reality, availing himself of all the formal elements of the Hispanic written tradition available to him. Evita’s Cuando los Combes Luchaban (“When the Combe Used to Fight”), published in 1953, is considered the foundational novel of Guinean letters. By comparing his novel to a breach in the monopoly of intellectual discrimination, Evita demonstrates that he is aware of the importance of his work. His words testify to his consciousness as a Guinean intellectual deeply aware of an intellectual tradition that had not been hitherto given a “written” voice.

Guinea’s transition to independence was achieved rather peacefully in 1968, primarily due to U.N. pressure on the Franco regime and local support for independence. However, as a result of Spain’s extractive colonialism, the new nation had little or no infrastructure, even in the capital city of Malabo. Once the elation of independence passed and elections were held, the newly elected president, Macías Nguema (1969–1979), instituted a military dictatorship. The Macías regime imposed Fang authority as the national paradigm. The repressive practices of the Macías regime caused the exile of many intellectuals and writers, leading to a period known as los años del silencio. Today, despite the fact that the Obiang government has implemented many changes and improvements, the paradigm of inequality established by Macías is still in force.

When I asked Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel about recent reforms, he responded, “The most important change is to see the dimming of repression. Now there are no beatings or arbitrary arrests in public. Clearly, if the previous regime had persisted I would not be a writer. Now people in the country can accuse the president of wrongdoing and live. In the Macías regime, a small criticism spelled a mortal threat.”

Today, Equatorial Guinea’s problems and inequalities have become aggravated by the extreme exploitation of the country’s natural resources. The discovery of oil in the ’90s marked the entry of Guinea into the world markets as a powerful oil producer, but this economic boom has not led to improvements for many of its citizens. Instead, it has installed a brand of capitalism that seeks to turn Guineans into consumers of Western goods. Most Guineans who can afford it drink water from imported plastic bottles; however, since there are no provisions for proper disposal, these symbols of Western modernity litter the landscape. Corruption is rampant, and life for most Guineans is lived under feudal conditions: Equatorial Guinea stands out as the only African country where the economic growth rate is among the highest in the world while the majority of the population lives in poverty.

Against this backdrop, the writers, artists and intellectuals of the various ethnicities have become a powerful force for integration, resistance and consciousness-raising through their literature and works of art. In his essays, Ávila Laurel examines the roots of Guinean inequalities, its history and politics, and the contradiction between state modernizing initiatives and life as it is lived by most Guineans. He also offers a penetrating critique of Guinea’s culture, traditions and attitudes, rooted in Guinea’s tragic and rich history, where he also finds the promise of Guinea’s future.

Against this backdrop, the writers, artists and intellectuals of the various ethnicities have become a powerful force for integration, resistance and consciousness-raising through their literature and works of art. In his essays, Ávila Laurel examines the roots of Guinean inequalities, its history and politics, and the contradiction between state modernizing initiatives and life as it is lived by most Guineans. He also offers a penetrating critique of Guinea’s culture, traditions and attitudes, rooted in Guinea’s tragic and rich history, where he also finds the promise of Guinea’s future.

In our interview he said, “The Guinean intellectual should denounce certain things that happen in our society, not because he is an intellectual but because there are some people who have the possibility of having their opinions disseminated and heard. Since this is a multiethnic nation, our cultures should reconcile or unify us. Cultural manifestations should be the expression of our Guinean-ness, with culture understood as its crystallization.”

Ávila Laurel explores the future of development in Equatorial Guinea in many of his essays, such as “Cómo convertir este país en un paraíso.” In our interview he said he wanted Guinea to enjoy a kind of development that takes into account ethnic diversity, the environment and the material and spiritual needs of the people. Although the term “barbarism” was once associated with indigenous peoples, and served as justification for the colonial enterprise, Ávila Laurel criticizes the barbarism of the despotic model adopted by Macías and his successors. “If someone says they are developed but they lack human rights, they are not,” he said. “If I dare to associate barbarism with Macías it is to relate his regime to Western culture. Macías was more the product of Western civilization than of African culture.”

The essays of Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel provide a contemporary insight on debates that dominated Latin American intellectual and political thought at the end of the 19th and early in the 20th century but are now part of Guinea’s intellectual discourse about the future. In the end, Ávila Laurel shares the same distrust of the economic benefits of “civilization” as his predecessor Leoncio Evita Enoy, who in his novel referred to it as a “sickness.” “Some believe they are superior to others because they come from a society that has learned to influence nature,” said Ávila Laurel. “Usually the so-called civilized society is the leader in the domain of nature. It is clear that those who have managed to dominate nature have abused this privilege. Guinea’s struggle is to find its place in the world without believing that it is a sin not to have taken the same steps as other countries on other continents.”

Rosario de Swanson teaches Spanish and Latin American literature at Marlboro. Her article “Autoenografía, espacio, identidad y resistencia en la narrativa fundacional de Guinea Ecuatorial: Cuando los combes luchaban (1953) de Leoncio Evita Enoy” is to be published in Revista Iberoamericana in 2011. Her interview with Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel, titled “Si alguien dice que está desarrollado y no goza de los derechos humanos, no lo está,” will appear in Hispanic Journal.

Cold War Femininity

Not unlike postcolonial African writers grappling with their national identity, acclaimed author Flannery O’Connor struggled with issues of femininity in the postwar era. Although most scholars have downplayed it, Elizabeth Ferrell ’11 chose to focus on this struggle in her Plan of Concentration. “Despite O’Connor’s persistent refusal to accept that her female characters experience a plight beyond religion, it is still apparent that she had a unique stance as a critically acclaimed female writer in the 1940s,” said Elizabeth. In studying the multifaceted female characters in O’Connor’s short fiction, Elizabeth concluded that their complexity extends to gender dynamics as well as religious themes. “Much like these characters can’t be contained within the traditional submissive female role, they also refuse to be pigeonholed into being plot devices for religious purposes.”

Not unlike postcolonial African writers grappling with their national identity, acclaimed author Flannery O’Connor struggled with issues of femininity in the postwar era. Although most scholars have downplayed it, Elizabeth Ferrell ’11 chose to focus on this struggle in her Plan of Concentration. “Despite O’Connor’s persistent refusal to accept that her female characters experience a plight beyond religion, it is still apparent that she had a unique stance as a critically acclaimed female writer in the 1940s,” said Elizabeth. In studying the multifaceted female characters in O’Connor’s short fiction, Elizabeth concluded that their complexity extends to gender dynamics as well as religious themes. “Much like these characters can’t be contained within the traditional submissive female role, they also refuse to be pigeonholed into being plot devices for religious purposes.”

Perpetual Farming

by Isaac Lawrence ’10

Engaging in multiple disciplines to address the same subject can sometimes result in mixed results. When economics and philosophy lead to different conclusions regarding agricultural conservation easements, Isaac Lawrence turns to his own experience on—and off—the ground.

Since its founding in 1977, the Vermont Land Trust (VLT) has had a hand in conserving nearly 8 percent of Vermont’s total land. The land trust’s primary means of conserving land lies in the purchase of development rights—what’s known as a “conservation easement.” Conservation easements allow lands to stay in traditional uses like forestry and agriculture, despite the financial allure of developable values on land. The money paid for development rights can prove the difference for struggling farmers between staying in and getting out of farming, but at what future cost?

Two years ago, I spent the summer working with the Vermont Land Trust and reflecting on the conservation easement as a tool for the conservation of farmland. I find two approaches in particular—the philosophical lens of Wendell Berry’s agrarian thought and the economic concept of “efficiency”—to be especially suitable to the task of considering conservation easements. I also find the two accounts at odds with one another, particularly concerning the perpetual nature of the VLT’s agricultural easements. Which perspective is right?

The premise of agrarianism is simple: Farming, food and family are the natural and best centers of our lives, and should remain so. This does not mean to imply, of course, that we should all go out and become farmers, but instead that we take as our model an agricultural life. Berry, often considered the father of contemporary agrarian thought, writes, “Connection is health.” In our modern industrial society, he says, we have “disconnections between body and soul, husband and wife, marriage and community, community and the earth.”

For Berry, the antidote is “good work.” “We are working well,” he writes, “when we use ourselves as the fellow creatures of the plants, animals, materials and other people we are working with.” This is the work that gives us health. And such work, for Berry, comes with good farming—that is, farming that respects the diversity and connectedness of our lives to all other life on this planet. Berry’s concept of good work asks that we know our farmers and make frequent and meaningful connections to them, and that we know where our food comes from.

For Berry, the antidote is “good work.” “We are working well,” he writes, “when we use ourselves as the fellow creatures of the plants, animals, materials and other people we are working with.” This is the work that gives us health. And such work, for Berry, comes with good farming—that is, farming that respects the diversity and connectedness of our lives to all other life on this planet. Berry’s concept of good work asks that we know our farmers and make frequent and meaningful connections to them, and that we know where our food comes from.

From an agrarian perspective, we can see that the work of the VLT is good work indeed: If good farming is happening on Vermont land, we must go to great lengths to protect it. Conservation easements serve to compensate farmers for protecting their land from development. This influx of cash allows many to continue farming, to pass farmland along to their children and to continue sustainable farming practices without cutting corners to save money. Indeed, Wendell Berry has himself donated development rights on his 117-acre Kentucky farm, citing his desire to keep the land in farming after he and his wife pass away.

The economics of conservation easements are a little more complicated. Easement prices are calculated as the difference between the full market value of a piece of property and its value for only the uses allowable under the terms of the easement—in this case, just agriculture. In other words, the price is what would be paid, in free exchange, solely for the rights to develop the property for nonagricultural uses; the farmer is paid the market price for this one right among the bundle that constitutes property ownership. It is clear that this is an economically efficient exchange, at least on the farmer’s end, so long as we assume that property markets function efficiently and without impediment from ill-advised regulation or market failures.

From an economic perspective, there’s one problem, however: conservation easements, as administered by the Vermont Land Trust, are perpetual. The lands in question must remain in farming forever. What if consumer preferences change in the future, and farming is no longer the most efficient use of the land? We can already assert that farming in the northeastern United States is a difficult, often inefficient, process. Even now, our desire to save farmland must be chalked up to cultural identity, or to aesthetics, or to some moral virtue associated with farming. What if, in the future, our willingness to pay for these things diminishes relative to some other use of the land? “Better” uses of conserved lands may well arise as preferences change, and there is a likelihood, quite high over a long time frame, that these uses will be more economically efficient. By limiting the opportunity of future generations to enact different sets of values on Vermont land, the VLT takes away what may be a very important right of future generations.

The difference between agrarian and economic perspectives on conservation easements hinges on this very issue. Agrarian thought suggests that there are some lasting values in natural systems, in what Berry calls the “Great Economy.” If these values exist outside of humanity, then they will continue to exist into the future, regardless of changes to humanity. In this, the perpetual nature of conservation easements is endorsed.

The difference between agrarian and economic perspectives on conservation easements hinges on this very issue. Agrarian thought suggests that there are some lasting values in natural systems, in what Berry calls the “Great Economy.” If these values exist outside of humanity, then they will continue to exist into the future, regardless of changes to humanity. In this, the perpetual nature of conservation easements is endorsed.

Economics, on the other hand, is concerned only with human wants. What is good, in terms of maximizing utility, is what is good for humanity. The good life is one of maximal utility for humans. As such, small-scale farming is only useful as long as we take it be so—as long as there are not uses of our scarce resources that we find more fruitful. For example, if we find that we would rather spend our time making art, or building cities, than farming, we may find that we would prefer to mechanize farm work, to disengage from the sources of our food and the like.

My experience on the ground with farmers working with the Vermont Land Trust has some bearing here. On one particular day, all three of the farmers we talked to recalled some initial hesitancy in the easement process. Giving up their rights to do what they will with the land ran counter to what I took to be a real premium on autonomy. The easement had been something of a compromise for each of them, and each had different ends in mind. What was shared was a deep respect for the land and for farming as a lifestyle. None of the farmers I spoke with wanted to see their farm get cut up into lots for houses, or sold for condominium development. They all expressed concern for the environmental health of their property. The conservation easement seemed a great conciliatory mechanism, and the farmers struck me as admirable for their hard work, for their commitment to good land use and for their practicality.

When we arrived at the third farm, we first went to take pictures that we would need to pitch the Project to the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board for funding. My supervisor thought it would be best to get a shot from above, and the crow’s nest at the top of the silo seemed the best place. He climbed the narrow ladder on the outside of the structure with what I later learned was characteristic energy and athleticism. Coming down, he assured me that I too needed to climb up, for the view. Afraid, I started up. Just as the drop below became utterly terrifying, the ladder acquired a cage, and only because of this was I able to get to the top. The view was, as my boss had suggested, spectacular. It was a perfect early July, Addison County day, and my view extended across miles of picturesque rolling farmland, with Lake Champlain and the Adirondacks in the distance. As a lifetime Vermonter, a descendent of Vermont dairy farmers on both sides, and as a longtime lover of the outdoors, I found the sight stirring.

Not surprisingly, my past predisposes me to some sympathy for Berry’s account and for perpetual conservation easements on farms—future generations’ potentially different wants be damned. At the same time, I also have great sympathy for the economic account: It suggests that what matters most is the aggregate welfare of all the people affected by a particular decision, rather than considering one person’s values more important than another’s. Which perspective is right?

Not surprisingly, my past predisposes me to some sympathy for Berry’s account and for perpetual conservation easements on farms—future generations’ potentially different wants be damned. At the same time, I also have great sympathy for the economic account: It suggests that what matters most is the aggregate welfare of all the people affected by a particular decision, rather than considering one person’s values more important than another’s. Which perspective is right?

In this case I can confidently say that preserving farmland for small, conscientious farmers is likely to be a good thing long into the future. My meetings with farmers left me with the feeling that, for a multitude of reasons, conservation easements were good for farmers and, for reasons like those that Berry articulated, for Vermont and Vermonters in general. Only my experience was capable of differentiating the two analytical frameworks I thought equally relevant to VLT’s work. This experience instills in me a powerful belief that the work of small, responsible farmers is valuable and, therefore, worth preserving.

Isaac Lawrence graduated in 2010 with a Plan in economics and philosophy, focusing on environmental management. He is now doing regional planning as an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer in Montpelier, Vermont, and will begin a master’s program in urban and regional planning in the fall.

Guitar Economy

While agrarian ideals conserve rural landscapes, “craft” ideals offer alternatives to struggling urban communities. John Whelan ’11 says, “The creative economy is a model for economic development applicable to de-industrialized communities, communities once reliant on older industrial structures such as the mills in New England.” John’s Plan explores the role of craft production, specifically guitar making, in the creative economy of southern Vermont, and compares the values of local luthiers to those of veteran producers like Gibson, Fender and Taylor. “Those large-scale producers aim to preserve a reputation that embraces some craft ideals, and also play an important role in the creative economy,” John says. What they typically lack, which he finds among local instrument makers, is a high level of community engagement crucial to a successful creative economy model. Go to our website to see a video of John describing his Plan work .

While agrarian ideals conserve rural landscapes, “craft” ideals offer alternatives to struggling urban communities. John Whelan ’11 says, “The creative economy is a model for economic development applicable to de-industrialized communities, communities once reliant on older industrial structures such as the mills in New England.” John’s Plan explores the role of craft production, specifically guitar making, in the creative economy of southern Vermont, and compares the values of local luthiers to those of veteran producers like Gibson, Fender and Taylor. “Those large-scale producers aim to preserve a reputation that embraces some craft ideals, and also play an important role in the creative economy,” John says. What they typically lack, which he finds among local instrument makers, is a high level of community engagement crucial to a successful creative economy model. Go to our website to see a video of John describing his Plan work .

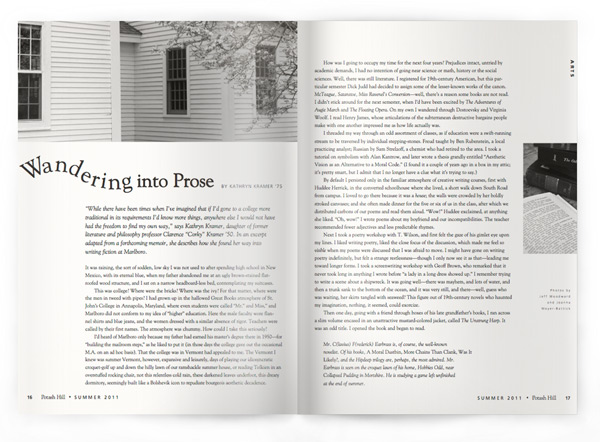

Wandering into Prose

by Kathryn Kramer ‘75

“While there have been times when I’ve imagined that if I’d gone to a college more traditional in its requirements I’d know more things, anywhere else I would not have had the freedom to find my own way,” says Kathryn Kramer, daughter of former literature and philosophy professor Clarence “Corky” Kramer ’50. In an excerpt adapted from a forthcoming memoir, she describes how she found her way into writing fiction at Marlboro.

It was raining, the sort of sodden, low sky I was not used to after spending high school in New Mexico, with its eternal blue, when my father abandoned me at an ugly brown-stained flat-roofed wood structure, and I sat on a narrow headboard-less bed, contemplating my suitcases.

This was college? Where were the bricks? Where was the ivy? For that matter, where were the men in tweed with pipes? I had grown up in the hallowed Great Books atmosphere of St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, where even students were called “Mr.” and Miss,” and Marlboro did not conform to my idea of “higher” education. Here the male faculty wore flannel shirts and blue jeans, and the women dressed with a similar absence of rigor. Teachers were called by their first names. The atmosphere was chummy. How could I take this seriously?

I’d heard of Marlboro only because my father had earned his master’s degree there in 1950—for “building the mailroom steps,” as he liked to put it (in those days the college gave out the occasional M.A. on an ad hoc basis). That the college was in Vermont had appealed to me. The Vermont I knew was summer Vermont, however, expansive and leisurely, days of playing our idiosyncratic croquet-golf up and down the hilly lawn of our ramshackle summer house, or reading Tolkien in an overstuffed rocking chair, not this relentless cold rain, these darkened leaves underfoot, this dreary dormitory, seemingly built like a Bolshevik icon to repudiate bourgeois aesthetic decadence.

I’d heard of Marlboro only because my father had earned his master’s degree there in 1950—for “building the mailroom steps,” as he liked to put it (in those days the college gave out the occasional M.A. on an ad hoc basis). That the college was in Vermont had appealed to me. The Vermont I knew was summer Vermont, however, expansive and leisurely, days of playing our idiosyncratic croquet-golf up and down the hilly lawn of our ramshackle summer house, or reading Tolkien in an overstuffed rocking chair, not this relentless cold rain, these darkened leaves underfoot, this dreary dormitory, seemingly built like a Bolshevik icon to repudiate bourgeois aesthetic decadence.

How was I going to occupy my time for the next four years? Prejudices intact, untried by academic demands, I had no intention of going near science or math, history or the social sciences. Well, there was still literature. I registered for 19th-century American, but this particular semester Dick Judd had decided to assign some of the lesser-known works of the canon. McTeague, Satanstoe, Miss Ravenel’s Conversion—well, there’s a reason some books are not read. I didn’t stick around for the next semester, when I’d have been excited by The Adventures of Augie March and The Floating Opera. On my own I wandered through Dostoevsky and Virginia Woolf. I read Henry James, whose articulations of the subterranean destructive bargains people make with one another impressed me as how life actually was.

I threaded my way through an odd assortment of classes, as if education were a swift-running stream to be traversed by individual stepping-stones. Freud taught by Ben Rubenstein, a local practicing analyst; Russian by Sam Strelzoff, a chemist who had retired to the area. I took a tutorial on symbolism with Alan Kantrow, and later wrote a thesis grandly entitled “Aesthetic Vision as an Alternative to a Moral Code.” (I found it a couple of years ago in a box in my attic; it’s pretty smart, but I admit that I no longer have a clue what it’s trying to say.)

By default I persisted only in the familiar atmosphere of creative writing courses, first with Huddee Herrick, in the converted schoolhouse where she lived, a short walk down South Road from campus. I loved to go there because it was a house; the walls were crowded by her boldly stroked canvases; and she often made dinner for the five or six of us in the class, after which we distributed carbons of our poems and read them aloud. “Wow!” Huddee exclaimed, at anything she liked. “Oh, wow!” I wrote poems about my boyfriend and our incompatibilities. The teacher recommended fewer adjectives and less predictable rhymes.

Next I took a poetry workshop with T. Wilson, and first felt the gaze of his gimlet eye upon my lines. I liked writing poetry, liked the close focus of the discussion, which made me feel so visible when my poems were discussed that I was afraid to move. I might have gone on writing poetry indefinitely, but felt a strange restlessness—though I only now see it as that—leading me toward longer forms. I took a screenwriting workshop with Geoff Brown, who remarked that it never took long in anything I wrote before “a lady in a long dress showed up.” I remember trying to write a scene about a shipwreck. It was going well—there was mayhem, and lots of water, and then a trunk sank to the bottom of the ocean, and it was very still, and there—well, guess who was waiting, her skirts tangled with seaweed? This figure out of 19th-century novels who haunted my imagination, nothing, it seemed, could exorcize.

Then one day, going with a friend through boxes of his late grandfather’s books, I ran across a slim volume encased in an unattractive mustard-colored jacket, called The Unstrung Harp. It was an odd title. I opened the book and began to read.

Then one day, going with a friend through boxes of his late grandfather’s books, I ran across a slim volume encased in an unattractive mustard-colored jacket, called The Unstrung Harp. It was an odd title. I opened the book and began to read.

Mr. C(lavius) F(rederick) Earbrass is, of course, the well-known novelist. Of his books, A Moral Dustbin, More Chains Than Clank, Was It Likely?, and the Hipdeep trilogy are, perhaps, the most admired. Mr. Earbrass is seen on the croquet lawn of his home, Hobbies Odd, near Collapsed Pudding in Mortshire. He is studying a game left unfinished at the end of summer.

A man with a horizontal football-shaped head and bushy mustaches peers with bafflement at the world. Mr. Earbrass is a writer, and his inveterate reluctance about everything, his perplexed participation in a world that misunderstands—this I recognized too. A writer’s life. I’d never read a description of one before.

Mr. Earbrass has rashly been skimming through the early chapters, which he has not looked at for months, and now sees TUH for what it is. Dreadful, dreadful, DREADFUL. He must be mad to go on enduring the unexquisite agony of writing when it all turns out drivel. Mad. Why didn’t he become a spy? How does one become one? He will burn the MS. Why is there no fire? Why aren’t there the makings of one? How did he get in the unused room on the third floor?

On I read: amazed, entertained, exhilarated. Accompanied. An afternoon not long after this I was taking a walk when a voice began to speak. I stopped walking and studied a stone wall in order better to listen to what was going on, seemingly distinct from me, in my mind.

“Edward was languishing next to the grape arbor,” I heard, “when suddenly it dawned on him; he could just as well think she’d died (though for his Lucia to do something so distinct!)—well, she had wilted. Certainly he should have known when she laughed at his ideas about islands….”

Lines of poems had used to arrive like that, but they had always been about me. Poetry I had used as a cri de coeur, a snapshot, an affirmation of self, but this was different. It felt different. I felt different, writing it. It was about someone else.

Inspired by the author of The Unstrung Harp, Edward Gorey, I had begun to discover a way out of anachronism. At the time I would no more have permitted an automobile or Saran Wrap into my prose than I would have gone streaking through the dining hall (an event so common that sometimes people no longer even looked up from their lunch when naked persons went screeching past the tables). I could use words like “asylum” or “embonpoint” and inhabit the world they constituted—just not quite.

The Mourning Dove (the decorous title of the novel I wrote for my senior Plan) owed a substantial debt not only to Edward Gorey, but to Henry James and Virginia Woolf. A Lambert Strether–like character, my poor protagonist deserved to be deceived by the woman he loved because he didn’t get it. He was the dupe. He had pulled the wool over his own eyes, so why shouldn’t others conspire with him against himself? This I evidently thought to be just. It would take me a long time to locate the source of my fascination with this archetypally dimwitted romantic—a complicated journey that would lead me back through the literature of my childhood—but I was experiencing the heady sense of participating for the first time in an ongoing conversation that really mattered to me.

By now I lived for the hour each week when I sat with T. in his office in Dalrymple, and he questioned me about the chapters I’d given him. Would X really do that? Why is Y so unkind to Z? Why this word instead of that? Why the scene in which poor Edward stands by the rhododendrons here and not later? I’d made these things up, but someone else felt proprietary about them. To write thinking of one thing only to discover that I’d made another, which I could then revise and adjust, the better to approximate…it—I could have sat from dawn till dusk listening to T. talk about my manuscript.

By now I lived for the hour each week when I sat with T. in his office in Dalrymple, and he questioned me about the chapters I’d given him. Would X really do that? Why is Y so unkind to Z? Why this word instead of that? Why the scene in which poor Edward stands by the rhododendrons here and not later? I’d made these things up, but someone else felt proprietary about them. To write thinking of one thing only to discover that I’d made another, which I could then revise and adjust, the better to approximate…it—I could have sat from dawn till dusk listening to T. talk about my manuscript.

I’d grown up in the religion that held that the Great Thoughts had been propounded, and it was up to us latecomers to find out about them. We were to have faith in the existence of truth while recognizing that we ourselves most likely would never attain it. All through my school years I’d been obsessed with getting right answers—fearing to get it wrong while not believing that I could get it right. Now I was discovering a way out of this paradox. Make things up. It can’t be wrong if it’s invented. It’s not real—it’s fiction.

Except, of course, it is real, in a sneaky, roundabout way that mere idea can never master. If you can get it right, fictionally right—and this is the lifelong mysterious work of it—you do speak the truth, in words from which it cannot be extricated. Unlike with poetry, the work, not I, was the subject under discussion. For the first time, I felt like a writer.

Kathryn Kramer teaches creative writing and literature at Middlebury College and is the author of several books, most recently Sweet Water. This excerpt is adapted from the forthcoming Missing History: The Covert Education of a Child of the Great Books.

Movement and Media Violence

Marlboro students often wander more than one academic path to find their way, as demonstrated by Heather Reed ’11, who finds surprising synergies between film and dance. “I want to change how people think about movement, and encourage the expansion of what has been called an ever-shrinking human movement vocabulary,” said Heather. Her interdisciplinary Plan paper looks at how violent media action affects movement, and how the growing glut of violent media has long-term physiological impacts. “Violent media and media saturation cause symptoms ranging from depression to obesity to increased aggression. I’m using tenets of dance movement therapy to help understand these symptoms and discover what can be done to create a better-moving, better-feeling society to combat the ill effects of violent media exposure.”

Marlboro students often wander more than one academic path to find their way, as demonstrated by Heather Reed ’11, who finds surprising synergies between film and dance. “I want to change how people think about movement, and encourage the expansion of what has been called an ever-shrinking human movement vocabulary,” said Heather. Her interdisciplinary Plan paper looks at how violent media action affects movement, and how the growing glut of violent media has long-term physiological impacts. “Violent media and media saturation cause symptoms ranging from depression to obesity to increased aggression. I’m using tenets of dance movement therapy to help understand these symptoms and discover what can be done to create a better-moving, better-feeling society to combat the ill effects of violent media exposure.”

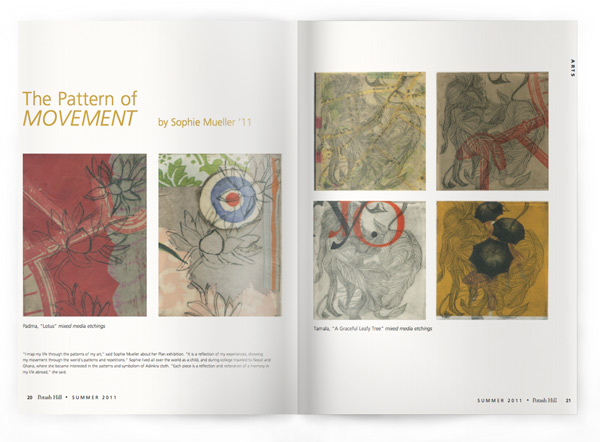

The Pattern of Movement

by Sophie Mueller ’11

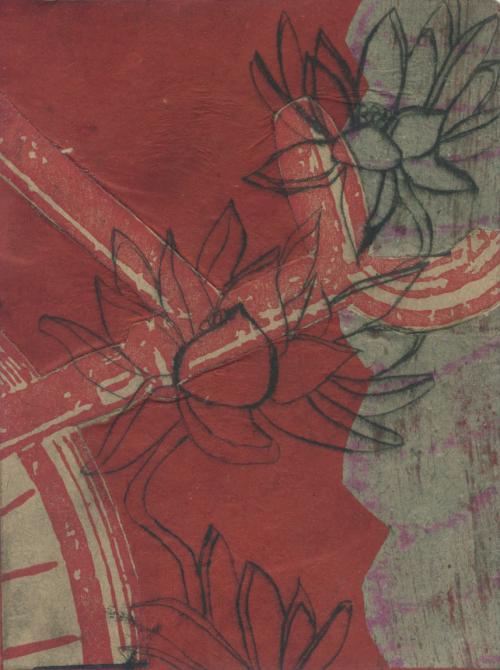

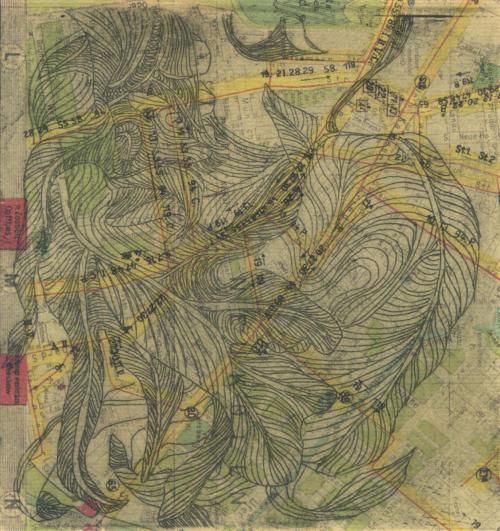

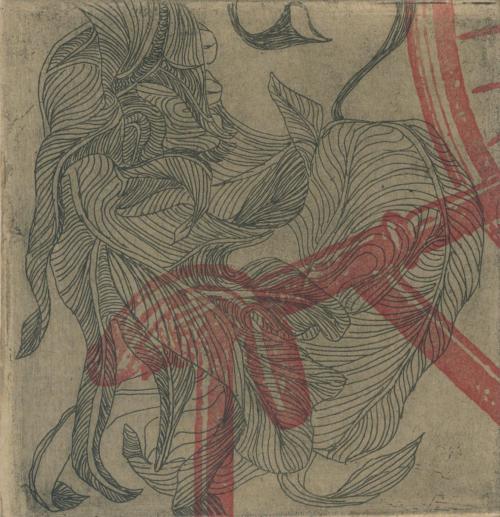

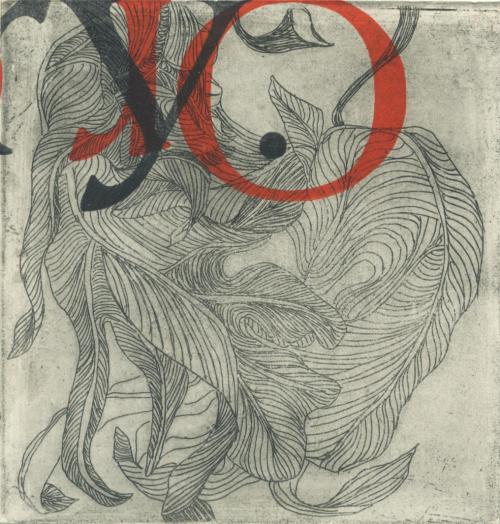

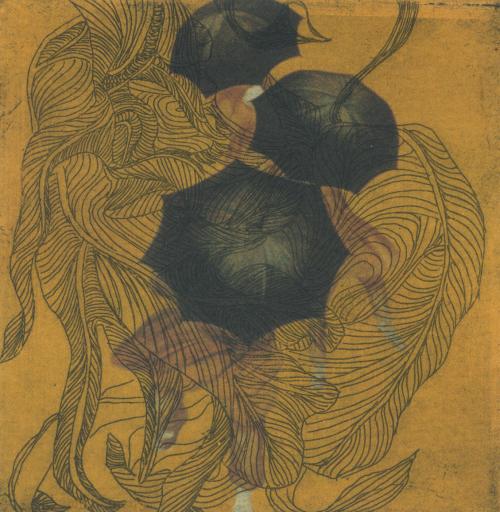

“I map my life through the patterns of my art,” said Sophie Mueller about her Plan exhibition. “It is a reflection of my experiences, showing my movement through the world’s patterns and repetitions.” Sophie lived all over the world as a child, and during college traveled to Nepal and Ghana, where she became interested in the patterns and symbolism of Adinkra cloth. “Each piece is a reflection and reiteration of a memory in my life abroad,” she said.

Padma, “Lotus” mixed media etchings

Padma, “Lotus” mixed media etchings

Tamala, “A Graceful Leafy Tree” mixed media etchings

Tamala, “A Graceful Leafy Tree” mixed media etchings

The Taste of Freedom

We asked our current and former Fulbright-supported Arabic language fellows from Egypt to reflect on the “18-day revolution” last January and the future of their country.

Fisal Younis Mubarak’s failure cannot be justified. He had all the power, resources and fertile environment for progress. Naturally, he had a quite good start: the economy was refreshed, tourism flourished and the occupied land was fully restored. However, his regime moved like a turtle. He lacked vision and strategy for the future, and he ignored the will of the people. He froze at the very moment he had restored the last inch of the Egyptian land. He saw nothing else, while people were fighting for bread and dignity.

Mubarak’s failure cannot be justified. He had all the power, resources and fertile environment for progress. Naturally, he had a quite good start: the economy was refreshed, tourism flourished and the occupied land was fully restored. However, his regime moved like a turtle. He lacked vision and strategy for the future, and he ignored the will of the people. He froze at the very moment he had restored the last inch of the Egyptian land. He saw nothing else, while people were fighting for bread and dignity.

Soon, the ghost of corruption appeared. Hypocrites gathered around him and lofted him to the rank of a god. They expanded rapidly like cancer and monopolized everything. The people endured low incomes and favoritism, until poverty provoked them. Some people warned that corruption was above knees and was about to cover noses. Yet, he never listened; he was blinded, or unwilling to see.

Now, people are very happy to kick the back of that corrupt regime. The losses have been great, but the benefits are priceless. People are happy and proud. Honorable

leaders are doing their best to help rebuild the country. We are all optimistic, and feel the delicious taste of freedom.

Marlboro’s Arabic fellow in the 2007–2008 academic year, Fisal Younis is now teaching English as a foreign language to high school students in Egypt and blogging on Arabic language and culture at Transparent Language, Inc.

Ahmed Salama Walking in San Francisco with one American and one Egyptian friend, in 2009, I was asked by the American, “What is the solution, from your point of view, to what is happening in Egypt?”

Walking in San Francisco with one American and one Egyptian friend, in 2009, I was asked by the American, “What is the solution, from your point of view, to what is happening in Egypt?”

“A revolution,” I answered.

The Egyptian friend said, “But there will be a lot of blood.”

“Each revolution should have some victims,” I replied.

At that time, I never thought that my words would come to be true. The fact is that we have had a real revolution, a revolution that has changed not only a regime, but also people’s minds and behaviors. It has changed the way other nations look at us, the Egyptians.

A lot of people still cannot believe that Egypt has changed. Many with private agendas are trying to take advantage of the current situation, such as the antirevolutionaries who have started to come back on the scene. I believe that it will take Egypt five to 10 years to overcome these problems and build a bridge to a real democracy. This will require a lot of hard work from all parties. However, many people are optimistic.

Marlboro’s Arabic fellow in the 2008–2009 academic year, Ahmed Salama is now head of the foreign languages department at Learning Services & Solutions Center in Al Mahall Al Kubra, Egypt.

Mahmoud Mahmoud What happened in Egypt is an answer to Langston Hughes’ “A Dream Deferred.” “What happens to a dream deferred?” the poem asks, concluding with the question, “does it explode?” Egypt definitely had to explode: that was inevitable. When I was in the United States, many people asked why the Egyptians didn’t fight. All the factors were ripe for us to rise; it was a matter of time, and the time has come.

What happened in Egypt is an answer to Langston Hughes’ “A Dream Deferred.” “What happens to a dream deferred?” the poem asks, concluding with the question, “does it explode?” Egypt definitely had to explode: that was inevitable. When I was in the United States, many people asked why the Egyptians didn’t fight. All the factors were ripe for us to rise; it was a matter of time, and the time has come.

Egyptians have finally spoken. For the first time in their seven-millennia-long history, Egyptians made the right choice. The dictator had to go. The fight is not over yet, though. Thirty years of dictatorship leave Egypt almost without a real middle class or strong infrastructure. Now it’s time to build. But the revolution has restored Egyptians’ pride and sense of belonging. The future is definitely going to be better in many ways.

All civilizations rise and fall. I foresee a rise coming: Egypt has shown the world how to revolt. Tahrir Square has become a liberation icon. Being the leading political and cultural power of the Arab world, and one of the most ancient human civilizations, Egypt spurs other nations to follow the example and fight for their freedom, their motto being “Fight like an Egyptian.”

Marlboro’s Arabic fellow in the 2009–2010 academic year, Mahmoud Mahmoud went on to received his master’s degree in African-American fiction and is now assistant lecturer of English language and literature at Sohag University in Egypt.

Ayman Yacoub After 30 years of Mubarak rule, Egyptian revolution was inevitable. It was a long period of sleeping, and in January the volcano erupted. Peaceful protesters all over the country demanded a life with honor.

After 30 years of Mubarak rule, Egyptian revolution was inevitable. It was a long period of sleeping, and in January the volcano erupted. Peaceful protesters all over the country demanded a life with honor.

Since Mubarek’s resignation, I have been hoping for fast and effective reform in Egypt. I can see it happening now, and I can sense it in the smile on Egyptians’ faces, telling the whole world how freedom tastes. In my opinion, an ideal government for Egypt will be the government that the masses vote for, a new parliament of our own choice. What makes me so optimistic about this is the constitutional changes that have already been made, which will not allow a president to run for more than two terms of four years each.

Egypt is the heart of the Middle East. I look at the effect of its revolution on her neighbors, as well as the whole world, and I don’t wonder. Years from now, this

revolution will be taught in history books in every corner of this universe: “How

peaceful Egyptians were; how powerfully and bravely they stood; how profound was the effect of their revolution.”

Marlboro’s Arabic fellow in the 2010–2011 academic year, Ayman Yacoub plans to pursue research in linguistics, translation studies, pedagogy and technology.

On and Off the Hill

All the news that fits, including the Embodied Learning Symposium, Movies from Marlboro, a class trip to the baths of Caracalla and a meeting called SymBiotic Art and Science. Plus commencement, of course, and faculty, students and staff worthy of note.

All the news that fits, including the Embodied Learning Symposium, Movies from Marlboro, a class trip to the baths of Caracalla and a meeting called SymBiotic Art and Science. Plus commencement, of course, and faculty, students and staff worthy of note.

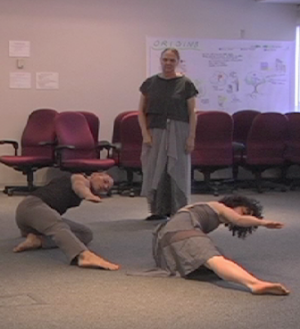

Symposium transcends mind-body dualism

In April, Marlboro students, faculty and staff joined with invited guests to explore concepts of embodied learning, drawing from both Eastern and Western traditions that embrace physicality, perception and context. The Embodied Learning Symposium consisted of four action-packed days of open classes, presentations and workshops on breaking down the Cartesian mind-body dualism often found in the classroom and studio.

“Embodied learning seems like something that ought to be intuitive,” said Asian studies professor Seth Harter, who organized the symposium in collaboration with the Vermont Performance Lab and with support from the Freeman Foundation for Undergraduate Asian Studies Initiative II. “Heads and bodies—when you see them apart it’s already too late. We all have bodies—we can’t think without them—and yet that fact often goes unrecognized, if not actively dismissed, in our liberal arts teaching work.”

Participants heard from leading scholars and practitioners of embodied learning such as acclaimed playwright and director Ain Gordon, who combines theater and performance art to bring forgotten histories to life. Livia Kohn, Daoist scholar and Boston University professor emerita, led participants through an embodied sense of Chinese cosmology, and University of Toronto professor Roxana Ng discussed “decolonized” learning. Participants had opportunities to experience T’aichi Ch’uan, West African dance, yoga, energy dance and Japanese movement traditions firsthand. But perhaps the most rewarding presentations were by Marlboro faculty who have embraced the concept of embodied learning in their own classes.

“In reading poems, we’re thinking about what it is we need to know about the poems, how we need to think about the range of emotions, changes in tone, the dynamics of the poem, in order to read it well,” said literature professor T. Wilson. Students from his Embodied Poetry class recited poems, with feeling, ranging from Robert Frost’s “Birches” to Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody blew up America.”

“In reading poems, we’re thinking about what it is we need to know about the poems, how we need to think about the range of emotions, changes in tone, the dynamics of the poem, in order to read it well,” said literature professor T. Wilson. Students from his Embodied Poetry class recited poems, with feeling, ranging from Robert Frost’s “Birches” to Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody blew up America.”

“I think there’s a kind of internalization that happens when you have to repeat a poem on demand,” said Ellie Roark ’12. “We embodied the mindset of the speaker.”

Students in Tim Segar’s class, The Body, shared some of their novel approaches to the age-old subject of the human form, from Shea Witzenberger’s ’12 bulbously corporeal soft sculptures to Aaron Evan-Browning’s ’12 electronic headband that translates facial expressions to sounds. Members of Cathy Osman’s class, Two Arms, Two Legs and a Head, shared the results of experimentally restraining their painting stroke to remind themselves of the physicality of painting. Students reported that they found the experiment freeing, even comforting, and the resulting figure paintings felt less contrived.

“‘I think therefore I am’ no longer sufficiently explains a lot of things that are going on in terms of social movements inspired by desires,” said politics professor Meg Mott in a presentation from her class, Spinoza & Freedom. She described going beyond students’ thoughts to make their emotional reactions to subjects part of the class discussion. “Maybe Spinoza’s tagline would be ‘I think I am affected, therefore I am empowered.”

Visiting language professor Michael Huffmaster discussed the bodily basis of semantics and thought, and ceramics professor Martina Lantin and visiting photography professor Lakshmi Luthra ’05 discussed art theory and practice. Anthropology professor Carol Hendrickson and Sari Brown ’11 talked about their recent visit to Bolivia, inspired by Sari’s field research there and by a course taught last fall by Carol and religion professor Amer Latif called Thinking Through the Body.

“Starting a few years ago, in the course of conversations with students and colleagues, I started to see a strange phenomenon—people started to talk about these ideas of embodiment,” said Seth, who led a discussion based on his class, Making Way: Daoist Ritual and Practice. “People started to question the epistemological significance of the connections between the mind and the body and the cost of ignoring those connections. They questioned bracketing out feelings or emotions or sensory input or physical limitation from the kind of work we were doing, even in history class or philosophy class. I saw the Embodied Learning Symposium as an opportunity for those conversations to come together.”

College launches film intensive

Film studies students have found significant opportunities to work with professor Jay Craven, from assisting on the set of his 2007 feature film, Disappearances, to collaborating on Marble Hill, a television sitcom based on a small, liberal arts college in Vermont. Next spring the college will take film studies to a new level, through an intensive program that partners college students with seasoned filmmakers for the production of a dramatic feature film starring professional actors and aimed for national release.

Film studies students have found significant opportunities to work with professor Jay Craven, from assisting on the set of his 2007 feature film, Disappearances, to collaborating on Marble Hill, a television sitcom based on a small, liberal arts college in Vermont. Next spring the college will take film studies to a new level, through an intensive program that partners college students with seasoned filmmakers for the production of a dramatic feature film starring professional actors and aimed for national release.

Movies from Marlboro, a semester-long film intensive, starts in January 2012 with a week at the Sundance Film Festival. This will be followed by “north country” literature and cinema study as well as hands-on preparation and production of a film based on Howard Frank Mosher’s award-winning novel Northern Borders.

“This new film intensive program grows out of my long experience working with young filmmakers and my years of producing and releasing north country films produced on significantly larger budgets,” said Jay. “Based on these experiences and new developments in independent film production and distribution, I believe that this Marlboro College film intensive will provide a rich learning opportunity and help chart a new course for how independent films get made and distributed.”

Eight film professionals will mentor up to 20 college students and play leading roles as department heads for the film. Independent filmmaker Chip Hourihan, who produced the Academy Award–nominated Frozen River, will partner with Jay to produce the film on a contract with the Screen Actors Guild. Based on their interest and experience, students will earn both college credit and professional film credit as they study, train and practice in every corner of production—as actors, camera operators, unit directors, producers, set designers, costume designers, production assistants and more.

“Marlboro College has, since its founding, believed in students’ potential to take on substantial leadership and responsibility and to challenge themselves on ambitious and potentially transformative Projects,” said Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president. “This Project is a perfect fit for us, and I’m especially pleased that we’ll launch it using the work of one of Vermont’s most talented writers, Howard Frank Mosher, who has done so much to enlarge our imagination of our region.”

“Marlboro College has, since its founding, believed in students’ potential to take on substantial leadership and responsibility and to challenge themselves on ambitious and potentially transformative Projects,” said Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, president. “This Project is a perfect fit for us, and I’m especially pleased that we’ll launch it using the work of one of Vermont’s most talented writers, Howard Frank Mosher, who has done so much to enlarge our imagination of our region.”

Jay envisions participation that will include undergraduate and graduate students in not only film but also theater, visual arts and photography. Students from other U.S. colleges are eligible to apply for the program, joining with Marlboro students on the Project.

“Motivated college students possess keen intelligence, formidable skills and a strong desire to work on Projects that engage them,” Jay said. “They can do the work required to make a first-class film, serving in leadership roles and guided by professionals. My own experience shows me that nothing helps to accelerate an emerging filmmaker’s path more quickly than this kind of intensive exposure, which can otherwise take years to achieve. We’re working to give students a chance—sooner than they might otherwise have—to intensify their practice and earn a substantial film credit to help launch their careers.”

For more information, go to movies.marlboro.edu or contact Jay Craven.

Students lay siege to Rome

“The ruins of Rome can be hard to comprehend secondhand,” said classics fellow William Guast, who taught a class this spring semester called Rethinking Rome: Power, Society and Faith in the Roman Empire. “Many sites are too large or too complex for their layout, function or impact to be fully comprehended in printed form.” In March, William’s class had a chance to experience Roman history firsthand, through the art, architecture and archaeology of the city of Rome itself and other sites nearby.

“The ruins of Rome can be hard to comprehend secondhand,” said classics fellow William Guast, who taught a class this spring semester called Rethinking Rome: Power, Society and Faith in the Roman Empire. “Many sites are too large or too complex for their layout, function or impact to be fully comprehended in printed form.” In March, William’s class had a chance to experience Roman history firsthand, through the art, architecture and archaeology of the city of Rome itself and other sites nearby.

“I experienced the actual scope of history,” said Sam King ’12, one of the nine students who participated and who is designing a Plan of Concentration on utopias. “Reading about Trajan’s Column, you don’t realize how big it is. That’s big in a symbolic sense, ancient and powerful and so on, but also very, very tall and hard to read. I was constantly in awe.”

William’s class considered how the Roman emperors tried to control their image through art and architecture, from the palaces they had built for themselves to the baths and amphitheaters with which they hoped to entertain the masses. Some of the highlights of their trip included the Colosseum (of course), the huge baths of Caracalla and a day trip to the Roman port town of Ostia to learn about the lives of the urban poor.

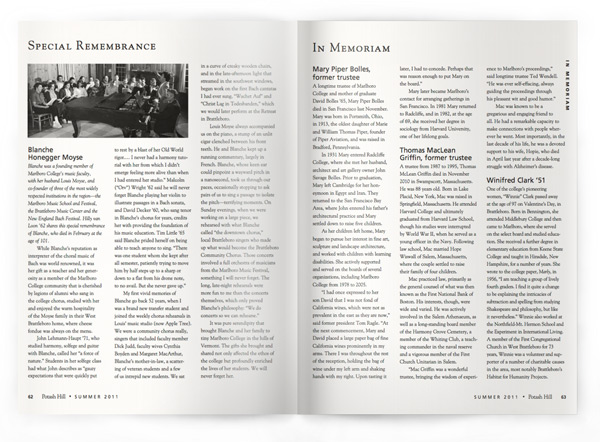

“A particular and unexpected highlight was the church of San Clemente, built on top of an early Christian basilica, which was itself built on top of a first-century temple to the god Mithras and an apartment block,” said William. The students were intrigued by the radically unfamiliar Roman religious system, visiting the great pagan temples such as the Pantheon, the dark catacombs where Christians and Jews were laid to rest and the monumental churches that heralded the final triumph of Christianity. “Another favorite was Rome’s cat sanctuary, situated in the ruins of four Roman temples.”