Meeting explores symbiosis of art and science

In March, a group of leading scholars in the life sciences, literature, visual arts and dance gathered at the National Science Foundation (NSF) in Arlington, Virginia, to explore what happens when artists and scientists work together. The conference, called “SymBiotic Art and Science,” was conceived by Marlboro President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell and colleague Dr. Christopher Comer, a neuroscientist and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Montana.

“Where the arts and sciences come together they are creating a new synthesis, new ways of knowing,” said Ellen. “The scientists call on the artists to ‘re-enchant the world,’ and the artists need the scientists to observe and understand the world. The artists talked about their experiments, and the scientists their intuitive leaps. They found that not only do artists and scientists inform each other’s work, they can also cooperate to generate new creativity. However, this kind of collaboration is not often recognized within academic arenas or by funding agencies.”

Co-sponsored by the NSF and the National Endowment for the Arts, the meeting involved 24 participants ranging from Liz Lerman, founding artistic director of the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, to University of Vermont theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman. Included were an art photographer who specialized in images of scientific experiments, a psychologist who analyzed literary characters and a rainforest ecologist who invited a Detroit rap artist into the forest canopy to communicate with urban youth about forest preservation. Participants from biology, astronomy, performance art, biomimicry, dance, painting, art conservation, bio-art, ecology and geology enriched the agenda as they mapped the range of possibilities.

“I have never considered my engagement in science as distinct from my activity as an artist,” said Bevil Conway, who teaches neuroscience at Wellesley College, with a focus on visual perception. “Although art and science differ in their modes of production, their expert communities and often their quantifiable utility, both avenues of investigation have provided me with a mechanism to appreciate, and hopefully uncover, the mysteries of perception. Both are fun.”

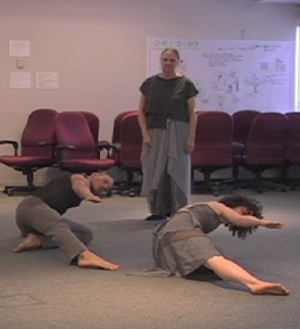

“The whole symposium was incredibly relevant to what we do here at Marlboro,” said dance professor Kristin Horrigan, who co-taught an Anatomy of Movement class with biology professor Jaime Tanner last fall. “I think that the big message I took home was that we could do a lot more of this, and it would be really healthy for our campus if we made a deliberate effort to create

more art-science connections.” Rounding out the Marlboro contingent were alumna Melanie Gifford ’73, who works at the National Gallery as a conservator of 16th- and 17th-century paintings, and film student Jesse Nesser ’13, who documented the meeting.

“There was a spontaneous and very poignant discussion about the conditions under which this work happens and flourishes, about generative environments,” said Ellen. The majority of participants who had academic affiliations were from small liberal arts colleges, and two from big universities admitted that they collaborated across disciplines in spite of their institutions. When participants from Europe pointed out that European colleges offer combination art-science degrees, it didn’t escape Ellen and Kristin and Melanie and Jesse that this is also possible at Marlboro. “When you think about generative environments, it is incredibly reinforcing of our Marlboro model,” said Ellen.