Commencement 2012

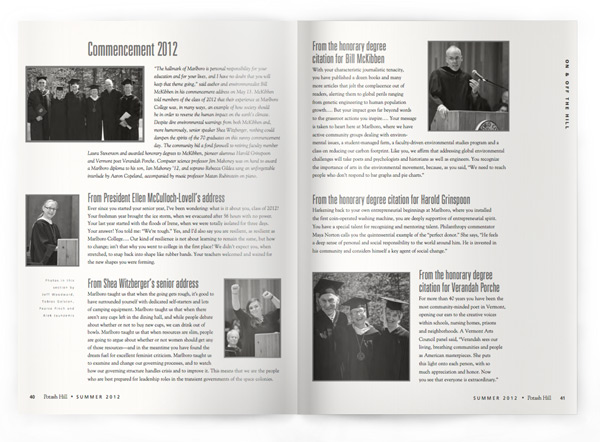

“The hallmark of Marlboro is personal responsibility for your education and for your lives, and I have no doubt that you will keep that theme going,” said author and environmentalist Bill McKibben in his commencement address on May 13. McKibben told members of the class of 2012 that their experience at Marlboro College was, in many ways, an example of how society should be in order to reverse the human impact on the earth’s climate. Despite dire environmental warnings from both McKibben and, more humorously, senior speaker Shea Witzberger, nothing could dampen the spirits of the 70 graduates on this sunny commencement day. The community bid a fond farewell to retiring faculty member Laura Stevenson and awarded honorary degrees to McKibben, pioneer alumnus Harold Grinspoon and Vermont poet Verandah Porche. Computer science professor Jim Mahoney was on hand to award a Marlboro diploma to his son, Ian Mahoney ’12, and soprano Rebecca Gildea sang an unforgettable interlude by Aaron Copeland, accompanied by music professor Matan Rubinstein on piano.

“The hallmark of Marlboro is personal responsibility for your education and for your lives, and I have no doubt that you will keep that theme going,” said author and environmentalist Bill McKibben in his commencement address on May 13. McKibben told members of the class of 2012 that their experience at Marlboro College was, in many ways, an example of how society should be in order to reverse the human impact on the earth’s climate. Despite dire environmental warnings from both McKibben and, more humorously, senior speaker Shea Witzberger, nothing could dampen the spirits of the 70 graduates on this sunny commencement day. The community bid a fond farewell to retiring faculty member Laura Stevenson and awarded honorary degrees to McKibben, pioneer alumnus Harold Grinspoon and Vermont poet Verandah Porche. Computer science professor Jim Mahoney was on hand to award a Marlboro diploma to his son, Ian Mahoney ’12, and soprano Rebecca Gildea sang an unforgettable interlude by Aaron Copeland, accompanied by music professor Matan Rubinstein on piano.

From President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s address

Ever since you started your senior year, I’ve been wondering: what is it about you, class of 2012? Your freshman year brought the ice storm, when we evacuated after 56 hours with no power. Your last year started with the floods of Irene, when we were totally isolated for three days. Your answer? You told me: “We’re tough.” Yes, and I’d also say you are resilient, as resilient as Marlboro College…. Our kind of resilience is not about learning to remain the same, but how to change; isn’t that why you went to college in the first place? We didn’t expect you, when stretched, to snap back into shape like rubber bands. Your teachers welcomed and waited for the new shapes you were forming.

Ever since you started your senior year, I’ve been wondering: what is it about you, class of 2012? Your freshman year brought the ice storm, when we evacuated after 56 hours with no power. Your last year started with the floods of Irene, when we were totally isolated for three days. Your answer? You told me: “We’re tough.” Yes, and I’d also say you are resilient, as resilient as Marlboro College…. Our kind of resilience is not about learning to remain the same, but how to change; isn’t that why you went to college in the first place? We didn’t expect you, when stretched, to snap back into shape like rubber bands. Your teachers welcomed and waited for the new shapes you were forming.

From Shea Witzberger’s senior address

Marlboro taught us that when the going gets rough, it’s good to have surrounded yourself with dedicated self-starters and lots of camping equipment. Marlboro taught us that when there aren’t any cups left in the dining hall, and while people debate about whether or not to buy new cups, we can drink out of bowls. Marlboro taught us that when resources are slim, people are going to argue about whether or not women should get any of those resources—and in the meantime you have found the dream fuel for excellent feminist criticism. Marlboro taught us to examine and change our governing processes, and to watch how our governing structure handles crisis and to improve it. This means that we are the people who are best prepared for leadership roles in the transient governments of the space colonies.

Marlboro taught us that when the going gets rough, it’s good to have surrounded yourself with dedicated self-starters and lots of camping equipment. Marlboro taught us that when there aren’t any cups left in the dining hall, and while people debate about whether or not to buy new cups, we can drink out of bowls. Marlboro taught us that when resources are slim, people are going to argue about whether or not women should get any of those resources—and in the meantime you have found the dream fuel for excellent feminist criticism. Marlboro taught us to examine and change our governing processes, and to watch how our governing structure handles crisis and to improve it. This means that we are the people who are best prepared for leadership roles in the transient governments of the space colonies.

From the honorary degree citation for Bill McKibben

With your characteristic journalistic tenacity, you have published a dozen books and many more articles that jolt the complacence out of readers, alerting them to global perils ranging from genetic engineering to human population growth…. But your impact goes far beyond words to the grassroot actions you inspire…. Your message is taken to heart here at Marlboro, where we have active community groups dealing with environmental issues, a student-managed farm, a faculty-driven environmental studies program and a class on reducing our carbon footprint. Like you, we affirm that addressing global environmental challenges will take poets and psychologists and historians as well as engineers. You recognize the importance of arts in the environmental movement, because, as you said, “We need to reach people who don’t respond to bar graphs and pie charts.”

With your characteristic journalistic tenacity, you have published a dozen books and many more articles that jolt the complacence out of readers, alerting them to global perils ranging from genetic engineering to human population growth…. But your impact goes far beyond words to the grassroot actions you inspire…. Your message is taken to heart here at Marlboro, where we have active community groups dealing with environmental issues, a student-managed farm, a faculty-driven environmental studies program and a class on reducing our carbon footprint. Like you, we affirm that addressing global environmental challenges will take poets and psychologists and historians as well as engineers. You recognize the importance of arts in the environmental movement, because, as you said, “We need to reach people who don’t respond to bar graphs and pie charts.”

From the honorary degree citation for Harold Grinspoon

Harkening back to your own entrepreneurial beginnings at Marlboro, where you installed the first coin-operated washing machine, you are deeply supportive of entrepreneurial spirit. You have a special talent for recognizing and mentoring talent. Philanthropy commentator Maya Norton calls you the quintessential example of the “perfect donor.” She says, “He feels a deep sense of personal and social responsibility to the world around him. He is invested in his community and considers himself a key agent of social change.”

Harkening back to your own entrepreneurial beginnings at Marlboro, where you installed the first coin-operated washing machine, you are deeply supportive of entrepreneurial spirit. You have a special talent for recognizing and mentoring talent. Philanthropy commentator Maya Norton calls you the quintessential example of the “perfect donor.” She says, “He feels a deep sense of personal and social responsibility to the world around him. He is invested in his community and considers himself a key agent of social change.”

From the honorary degree citation for Verandah Porche

For more than 40 years you have been the most community-minded poet in Vermont, opening our ears to the creative voices within schools, nursing homes, prisons and neighborhoods. A Vermont Arts Council panel said, “Verandah sees our living, breathing communities and people as American masterpieces. She puts this light onto each person, with so much appreciation and honor. Now you see that everyone is extraordinary.”

For full transcripts of addresses and citations, a list of 2012 graduates and their Plans of Concentration as well as photos and videos, go to www.marlboro.edu/news/commencement/2012.

Climate of Hope: From Bill McKibben’s address

I am so grateful that the year that began with Irene for you all ends on this beautiful, glorious day. It must be said that even beautiful, glorious days now carry a kind of freight that they didn’t in the past. I don’t know about you, but that March heat wave that we had—those beautiful days when we were all out wandering around in shorts and t-shirts— at the back of our minds we had that sense that this was not how it should be. And it isn’t how it should be.

I am so grateful that the year that began with Irene for you all ends on this beautiful, glorious day. It must be said that even beautiful, glorious days now carry a kind of freight that they didn’t in the past. I don’t know about you, but that March heat wave that we had—those beautiful days when we were all out wandering around in shorts and t-shirts— at the back of our minds we had that sense that this was not how it should be. And it isn’t how it should be.

The burden of what we have done to this world lays a little heavy on the older among us, as we look at you. The great wish of people, I think, is to pass on to their children and grandchildren a world in better shape than the one that they were born into, and we have failed at that task. The world is not in as good shape as it was when we were born…. The most important thing that has happened so far in your life is that this planet left what scientists call the Holocene, a 10,000-year period of benign climatic stability that underwrote the rise of human civilization. Sometime in the last 20 years we crossed some invisible line to what comes next. The only question now is how far down that path we will go, and that will largely be up to you.

It is not just the physical world that, in certain ways, is less than it should be. Our society, too, is in certain ways not what we would hope. Fifty years ago, the average American had twice as many close friends, statistically, as the average American today. It’s a very, very large loss, and it explains why statistically we find that people in our society are nowhere near as happy as they were, no longer feel as satisfied with their lives as they did some decades ago. These things aren’t ideological, they’re physics and chemistry and sociology, and they’re not determinant either. The question is how to turn them around and keep them from getting worse, and then reverse them: to build a world that you can leave with somewhat more pride than we do.

The hallmark of Marlboro is personal responsibility for your education and for your lives, and I have no doubt that you will keep that theme going in all the ways that one can be responsible to one’s community and to one’s earth—that you will do those things you can. I want to add, however, that as you go forward you also need to (and I know you already do) think about it well beyond the bounds of your own individual selves and think a lot about the role that you can play in building communities strong enough to really turn things around.

I deal with climate change, the most pressing problem humans have ever faced. It is very clear why we’re making no progress. The fossil fuel industry, the richest enterprise humans have ever engaged in, has been able to use that financial power to block change. They will always have more money than the rest of us, and so, if we’re going to turn them around, we will need to find other currencies to work in. Those are mostly the currencies of community, passion, spirit, creativity: the things that build movements. It has been fun to watch these movements build over the last few years. We started 350.org four years ago with myself and seven seniors at Middlebury—people exactly like you—and now it’s grown to be this great, grassroots climate change movement around the world, active in every country but North Korea. And we may not get there anytime soon.

One of the things I always think when I’m at a college, but especially here, is that while you’ve been busy studying important things, the real thing you’ve been studying has less to do with the various disciplines…than it does with the community in which you’re embedded. When people come back to the place where they had their college years, and when they say, “Those were the best years of my life,” part of what they’re remembering is how much they enjoyed their classes. But mostly what they’re remembering is the incredible rightness of being in a place where, for four years, you get to live the way that most human beings have lived for most of human history—in close physical and emotional proximity to a lot of other people. And sometimes that’s a complete pain, you know? But most of the time it’s magnificent to always have people to bounce ideas off of; that’s what we evolved to do, and the wrong turn we took as a society was to get away from that.

The reason that we have half as many friends as people 50 years ago is that we spent the intervening five decades hard at work on the project of building bigger houses farther apart from each other. And that’s also the reason why we pour so much carbon into the atmosphere. One of the ironies of higher education, or education in general, is that we bring you here and you have this wonderful community, but one of the subtexts is that you now are equipped to go out and earn enough money so that you never have to live this way again. But there is no absolute requirement that you do that, and if you’re wise, and I think you are, you’ll look for ways all along to try and take some of this community and make it work in the rest of your lives.

I’ve got to tell you the truth, which is that I don’t know if we’re going to win this epic fight about the climate. There are scientists, as you know, who think we’ve waited rather late to get started, and there are political scientists who think the odds are simply too great and there’s too much money on the other side. And they might be right…. But I do know that all around the world, including in places that have done nothing to cause this problem, there are people ready and willing to fight in all the ways they can. It is always such an honor for me to get to be in those communities. It is such an honor to get to be in this one and say that I very much look forward, in the years ahead, to just getting to stand side by side with you and take on these problems and see where we go. There are no guarantees, except that involvement and engagement and the kind of love that it comes from is the thing that makes all of this worthwhile.

Academic Prizes

The Rebecca Willow Prize, established in 2008 in memory of Rebecca Willow, class of 1995, is awarded to a student whose presence brings personal integrity and kindness to the community and who unites an interest in human history and culture with a passion for the natural world. Brandon Willits and Jacquelyn Ward

The Audrey Alley Gorton Award is given in memory of Audrey Gorton, Marlboro alumna and member of the faculty for 33 years, to the student who best reflects the Gorton qualities of: passion for reading, an independence of critical judgment, fastidious attention to matters of style and a gift for intelligent conversation. Rebecca Gildea and Abigail Weiss

The Hilly van Loon Prize, established by the class of 2000 in honor of Hilly van Loon, Marlboro class of 1962 and staff member for 23 years, is given to the senior who best reflects Hilly’s wisdom, compassion, community involvement, quiet dedication to the spirit of Marlboro College, joy in writing and celebration of life. Casey Friedman and Eleanor Roark

The William Davisson Prize, created by the Town Meeting Selectboard and named in honor of Will Davisson, who served as a faculty member for 18 years and as a trustee for 22 years, is awarded to one or more students for extraordinary contributions to the Marlboro community. Cookie Harrist and Jack Rossiter-Munley

The Ryan Larsen Memorial Prize was established in 2006 in memory of Ryan Jeffrey Larsen, who felt transformed by the opportunities to learn and grow within the embrace of the Marlboro College community. It is awarded annually to a junior or senior who best reflects Ryan’s qualities of philosophical curiosity, creativity, compassion and spiritual inquiry. Alexia Boggs, Jonathan Wood and Trevor Rickenbrode

The Helen W. Clark Prize is awarded by the visual arts faculty for the best Plan of Concentration in the fine arts. Joanna Moyer-Battick and Mara Eagle The Sally and Valerio Montanari Theater Prize is awarded annually to a graduating senior who has made the greatest overall contribution to the pursuit of excellence in theater production. Sarah Grace Leathrum

The Dr. Loren C. Bronson Award for Excellence in Classics, established by the family of Loren Bronson, class of 1973, is awarded to encourage undergraduate work in classics. Chester Harper

The Roland W. Boyden Prize is given by the humanities faculty to a student who has demonstrated excellence in the humanities. Roland Boyden was a founding faculty member of the college, acting president, dean and trustee. Emma Goldhammer

The Buck Turner Prize is awarded to a student who demonstrates excellence in the natural sciences, who uses interdisciplinary approaches and who places his or her work in the context of larger questions. Kathryn Lyon, Clare Riley and Alex Hiam

The Freshman/Sophomore Essay Prize is given annually for the best essay written for a Marlboro course. Aidan Keeva

The Robert E. Engel Award, established in 2011 in honor of Bob Engel, Marlboro faculty member for 36 years, is awarded to a student who demonstrates Bob’s passion for the natural world and his keen powers of observation and inquiry as a natural historian. Joella Simons Adkins