House of Straw and Wind: Exile in Southern Denmark

By Kate Hollander ’02

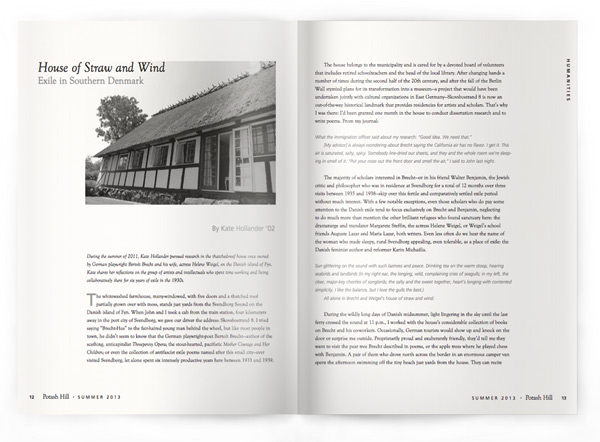

During the summer of 2011, Kate Hollander pursued research in the thatched-roof house once owned by German playwright Bertolt Brecht and his wife, actress Helene Weigel, on the Danish island of Fyn. Kate shares her reflections on the group of artists and intellectuals who spent time working and living collaboratively there for six years of exile in the 1930s.

The whitewashed farmhouse, many-windowed, with five doors and a thatched roof partially grown over with moss, stands just yards from the Svendborg Sound on the Danish island of Fyn. When John and I took a cab from the train station, four kilometers away in the port city of Svendborg, we gave our driver the address: Skovsbostrand 8. I tried saying “Brecht-Hus” to the fair-haired young man behind the wheel, but like most people in town, he didn’t seem to know that the German playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht—author of the scathing, anticapitalist Threepenny Opera; the stout-hearted, pacifistic Mother Courage and Her Children; or even the collection of antifascist exile poems named after this small city—ever visited Svendborg, let alone spent six intensely productive years here between 1933 and 1939.

The whitewashed farmhouse, many-windowed, with five doors and a thatched roof partially grown over with moss, stands just yards from the Svendborg Sound on the Danish island of Fyn. When John and I took a cab from the train station, four kilometers away in the port city of Svendborg, we gave our driver the address: Skovsbostrand 8. I tried saying “Brecht-Hus” to the fair-haired young man behind the wheel, but like most people in town, he didn’t seem to know that the German playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht—author of the scathing, anticapitalist Threepenny Opera; the stout-hearted, pacifistic Mother Courage and Her Children; or even the collection of antifascist exile poems named after this small city—ever visited Svendborg, let alone spent six intensely productive years here between 1933 and 1939.

The house belongs to the municipality and is cared for by a devoted board of volunteers that includes retired schoolteachers and the head of the local library. After changing hands a number of times during the second half of the 20th century, and after the fall of the Berlin Wall stymied plans for its transformation into a museum—a project that would have been undertaken jointly with cultural organizations in East Germany—Skovsbostrand 8 is now an out-of-the-way historical landmark that provides residencies for artists and scholars. That’s why I was there: I’d been granted one month in the house to conduct dissertation research and to write poems. From my journal:

What the immigration officer said about my research: “Good idea. We need that.”

[My advisor] is always wondering about Brecht saying the California air has no flavor. I get it. This air is saturated, salty, spicy. Somebody line-dried our sheets, and they and the whole room we’re sleeping in smell of it. “Put your nose out the front door and smell the air,” I said to John last night.

The majority of scholars interested in Brecht—or in his friend Walter Benjamin, the Jewish critic and philosopher who was in residence at Svendborg for a total of 12 months over three visits between 1935 and 1938—skip over this fertile and comparatively settled exile period without much interest. With a few notable exceptions, even those scholars who do pay some attention to the Danish exile tend to focus exclusively on Brecht and Benjamin, neglecting to do much more than mention the other brilliant refugees who found sanctuary here: the dramaturge and translator Margarete Steffin, the actress Helene Weigel, or Weigel’s school friends Auguste Lazar and Maria Lazar, both writers. Even less often do we hear the name of the woman who made sleepy, rural Svendborg appealing, even tolerable, as a place of exile: the Danish feminist author and reformer Karin Michaëlis.

Sun glittering on the sound with such laziness and peace. Drinking tea on the warm stoop, hearing seabirds and landbirds (in my right ear, the longing, wild, complaining cries of seagulls; in my left, the clear, major-key chortles of songbirds; the salty and the sweet together, heart’s longing with contented simplicity. I like the balance, but I love the gulls the best.)

Sun glittering on the sound with such laziness and peace. Drinking tea on the warm stoop, hearing seabirds and landbirds (in my right ear, the longing, wild, complaining cries of seagulls; in my left, the clear, major-key chortles of songbirds; the salty and the sweet together, heart’s longing with contented simplicity. I like the balance, but I love the gulls the best.)

All alone in Brecht and Weigel’s house of straw and wind.

During the wildly long days of Danish midsummer, light lingering in the sky until the last ferry crossed the sound at 11 p.m., I worked with the house’s considerable collection of books on Brecht and his co-workers. Occasionally, German tourists would show up and knock on the door or surprise me outside. Proprietarily proud and exuberantly friendly, they’d tell me they want to visit the pear tree Brecht described in poems, or the apple trees where he played chess with Benjamin. A pair of them who drove north across the border in an enormous camper van spent the afternoon swimming off the tiny beach just yards from the house. They can recite poems from Brecht’s volume Svendborger Gedichte, “Svendborg Poems,” which describe this house as a place of profound but uneasy refuge. They wonder why Brecht, that sly and worldly poet of the cities, would spend six years in this former farmhouse on a Danish island.

Their English is good and my German is fair, but I don’t get around to telling them that the answer to their question lies in Vienna, where Michaëlis, author of the controversial novel The Dangerous Age, taught at an extraordinary school—a school whose list of teachers and graduates included some of the great artists and thinkers of Central Europe, including one with whom the Marlboro community will be familiar: Ruldof Serkin. Michaëlis became a mentor to the aspiring young actress Helene Weigel through this school, and years later it was to Michaëlis’s house on the tiny island of Thurø that Weigel and Brecht first came in flight from Germany following Hitler’s rise to power. With funds lent by Michaëlis herself, Brecht and Weigel purchased the thatched-roof house at Skovsbostrand 8. You don’t hear the name Karin Michaëlis very much these days, but in Southern Fyn, it’s everywhere.

The museum is the only remaining “work house” in Scandinavia. You buy tickets and you go in and see what a miserable, horrible place it was and how everyone suffered before the welfare state. I wander around for a while trying to find the archives. Eventually I see a little map, go back around the side (for the second time), open the door…nobody in sight…ring the bell…a woman comes. Yes, it is the archives. Hanne will help me.

Hanne comes. She is a very nice energetic archive lady. At first she tells me she doesn’t have anything for me…the library archive would have it…or this other archive that covers the part of Svendborg the house is in. Then I see she has a calendar with a picture of KM. “Karin Michaëlis!” I say. “I am also studying her.” Oh! Well, now she might have things for me… she calls in another woman, also named Hanne. They scurry around. Yes, they have something. A whole file on the Brecht house. Another on KM. They show me into the big reading room…long table, handsome and homey.

They give me some gloves so I can look at some photos of Michaëlis at her house, Torrelore. She has great hats in every photo. I say I like her hats. Hanne says, “She was a very special lady.” There is such warmth here when anyone speaks about her. But, they all insist, she isn’t known in Denmark now.

The spring before I came to Svendborg, I was in touch with members of the Karin Michaëlis Society, which includes scholars and amateurs interested in her work and life. While at Skovsbostrand 8, three of them come to visit. I provide tea and miserable biscuits that I ruin through my inexperience with baking by weight and miscalculating temperatures in Celsius. They arrive with their arms full of things for me, whom they’ve never met: a huge bag of beautiful breads from a bakery on Thurø, a big tub of home-grown red currants, articles to read, a book. Languages fly: German, English, Danish, even Swedish, as we struggle to communicate, share, and read out loud to one another. Before they leave, they hug me tight. I’m almost undone by their kindness and generosity, which they insist is in the spirit of the selfless-to-afault Michaëlis herself. In tears as they drive away, I feel sure I’ve been touched, through them, by her warm and giving spirit.

Lightning over the ocean last night, and wind and rain. I feel safe in this little house, even with its five doors for escaping through.

Lightning over the ocean last night, and wind and rain. I feel safe in this little house, even with its five doors for escaping through.

A thatched roof is just as good as any other at keeping the rain out. This became obvious to me when a storm parked just off the coast for 72 hours toward the end of July; the rain lashed and the wind was so strong I could barely push open the door to go outside. But only the first inch or two of the reeds that make up the roof were soaked through; the rest of the thatch was totally dry.

A thatched roof needs to be replaced every 50 years or so. These days, historiographies last a much shorter time—and that’s probably not a bad thing. In the 60 years since Brecht’s death, scholars have understood him in an ever-evolving variety of ways: first as a solitary (if philandering) genius, then as an exploiter of women and even a plagiarist, and finally as the vital but not dominating center of a series of collaborative circles. I’m hoping to go a step further by showing how this particular community of artists, intellectuals, and socialists actually worked together in exile. The house at Skovsbostrand 8 is at the heart of that—reminding us that even great intellectuals have material needs for shelter, nourishment, and comfort. More than just a place of refuge, this house was a laboratory for artistic and intellectual collaboration, a place where various and sometimes contradictory ideas of socialism came into contact with the necessities of exile.

A Ph.D. candidate in modern European history at Boston University as well as a published poet, Kate Hollander is writing her dissertation on the artists and intellectuals who gathered at Skovsbostrand 8. She lives in Boston with John Coakley ’02.

Escaping to Home

“It is easy to spend a lot of time alone in the woods with oneself. It is truly hard to be alone with other people,” said Dane Fredericks ‘13, who did his Plan of Concentration on the theme of escape in American literature, focusing on Mark Twain, Flannery O’Conner, and Cormac McCarthy. His independent study was an essay based on a hitchhiking trip he took over winter break, comprising an oral history of the people he met. “I think that I made most of the people I encountered a little bit uncomfortable. Certainly they often made me uncomfortable,” said Dane, who learned as much about himself as his subjects. “I discovered that all the best stories came when I stopped trying to be someplace else and admitted that I wanted to be home. Home anywhere.”

“It is easy to spend a lot of time alone in the woods with oneself. It is truly hard to be alone with other people,” said Dane Fredericks ‘13, who did his Plan of Concentration on the theme of escape in American literature, focusing on Mark Twain, Flannery O’Conner, and Cormac McCarthy. His independent study was an essay based on a hitchhiking trip he took over winter break, comprising an oral history of the people he met. “I think that I made most of the people I encountered a little bit uncomfortable. Certainly they often made me uncomfortable,” said Dane, who learned as much about himself as his subjects. “I discovered that all the best stories came when I stopped trying to be someplace else and admitted that I wanted to be home. Home anywhere.”