Paul Nelsen takes a bow

When theater professor Paul Nelsen first came to Vermont in 1971, fresh out of graduate school, it was to work at Windham College in Putney, where he helped establish an innovative and ambitious theater program. The program thrived, but Windham’s enrollment decreased from 1,000 to 300 students in a matter of six years, forcing the college to close. Paul began working with a consulting group of which Marlboro College was one of the first clients, and the rest is Potash Hill history: Marlboro invited Paul to join esteemed theater professor Geoffry Brown on the faculty, and he started in January 1978. He retires this year after 35 years on, and off, the Marlboro stage.

When theater professor Paul Nelsen first came to Vermont in 1971, fresh out of graduate school, it was to work at Windham College in Putney, where he helped establish an innovative and ambitious theater program. The program thrived, but Windham’s enrollment decreased from 1,000 to 300 students in a matter of six years, forcing the college to close. Paul began working with a consulting group of which Marlboro College was one of the first clients, and the rest is Potash Hill history: Marlboro invited Paul to join esteemed theater professor Geoffry Brown on the faculty, and he started in January 1978. He retires this year after 35 years on, and off, the Marlboro stage.

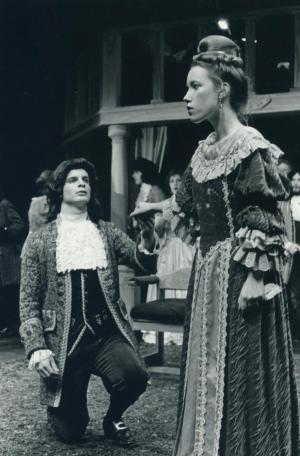

“The first play I directed at Marlboro in the spring semester 1978 was Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler,” said Paul, who immediately upon starting at Marlboro launched into theatrical experimentation with great energy. “I had a group of wonderful students eager to get their teeth into some classical drama.”

During his first semester at the college, Paul and his students altered Whittemore Theater, rebuilding the stage and removing the balcony in order to expand the playing space. Intensive rehearsals, often entailing four-hour sessions, six days a week, with set building on Saturdays, spanned a total of six weeks. That same semester, Paul directed two additional plays: a version of Spoon River Anthology and Michael Cristofer’s The Shadow Box.

“I was young, ambitious, and maybe a little foolish,” Paul grinned. “But I continued with that level of intensity for many years, trying to do everything myself. There was no tech director, no work-study crews. All design, construction, and production work was accomplished by me and some dedicated students.”

In 1979, during the January “Winterim”—a period designed for students to explore new horizons—Paul, along with his wife, kids, and mother-in-law, led a student trip to London, the world’s mecca for theater. The program proved so successful that he repeated it a couple of years later, and subsequently expanded participation to include Marlboro College trustees, other faculty, and friends of the college from the local community. Paul’s trips to London have continued on a regular basis to this day: what began with 11 students and Paul’s family has grown to three trips a year, with over 120 participants from across North America.

“Paul was an excellent leader on our trip to Britain—heavenly days of castles, cathedrals, contemporary theater, and Shakespeare out the wazoo,” commented Gina DeAngelis ’94. “He didn’t just teach acting or directing, he taught us theater folks how to use our talent and develop our skills to reflect, for an audience, life itself.”

In 1983, inspired by his London experiences, Paul invited a former member of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Ted Valentine, to play the lead role in King Lear. The production involved a yearlong immersion process, with a weekly close reading of the play in the fall semester and rehearsals beginning in the Winterim, and featured students as well as members of the community.

“It was an immense project,” recalled Paul. “Three quarters of the auditorium at Persons was the stage. There were only a hundred or so seats at the back of the auditorium. It was an immense space with giant stone arches.”

The following year Paul worked on Sophocles’ Antigone and a Harold Pinter play, The Birthday Party. These high-profile projects required Paul to raise money, some of which came out of his own pocket. Paul was selfreportedly obsessed with achieving something that was exceptional, beyond standard intercollegiate quality. With a lack of technical infrastructure and reliable financial support, however, he became unable to sustain the energy for such an ambitious program.

“At first, when I started, it was possible to get by—perhaps by sheer mania, but I cannot say I regret that,” Paul joked. “The theater program has changed over the years. When I first came here, there was an emphasis on performance as a medium for learning. In the first 15 years I was here, I directed 28 productions. Students collaborated actively in the design and production aspects, but like Geoff Brown before me I was involved hands-on with all elements of putting on the shows—as well as teaching a full load of classes and tutorials.”

In 1985, Paul sought to expand Marlboro’s capabilities by helping a group of local citizens purchase the former arts building at Windham College, which they renamed the River Valley Playhouse and Art Center. The project aimed to collaborate with Middlebury and Smith colleges to develop a summer theater program with professional actors, students, and faculty from all three institutions and produce a summer season of three or four plays. Concerned about the economic prospects and under financial stress, Marlboro pulled out of the project before its launch. Paul adjusted, using community actors to deliver a season of plays: Chekhov’s The Seagull, Good by C.P. Taylor, and Noël Coward’s Present Laughter. “They were artistically successful, and ticket sales covered all expenses,” Paul remarked with a smile.

Over the next decade, Paul continued to support student productions but decreased the frequency of his own. In 1996, he directed his final play, Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, and began to focus his teaching on dramatic literature as well as on exploring the history and practices of theater and film from diverse angles, often in collaboration with other faculty.

“The impressive works produced by Marlboro students are the greatest testaments to Paul’s ability to nurture and inspire,” declared Edward Isser, professor and chair of theater at Holy Cross College. “Possessing an encyclopedic knowledge of theater and a generosity of spirit, Paul has been a remarkable teacher, a treasured colleague, and a transformative mentor.”

“One of the reasons I chose Marlboro College was so that I would have professors who really cared about, and interacted with, their students,” said Jesse Nesser ’13. “Paul Nelsen turned out to be exactly the kind of teacher I had hoped for. His curiosity, passion, insight, and dedication extend beyond his department and his classroom.”

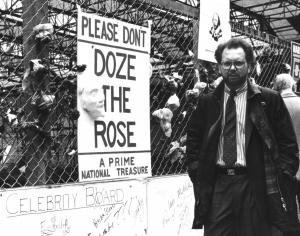

In the mid-1990s, Paul was one of a dozen National Endowment for the Humanities Fellows who convened at the Folger Shakespeare Institute in Washington, D.C., to explore practices of teaching Shakespeare through performance. His research and publications in academic journals on Early Modern English playhouses resulted in an invitation to serve from 1990 to 2002 on the Academic Advisory Board for the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London.

In 2007 Paul collaborated with visual art professor Tim Segar and music professor Stan Charkey to create a field-based, summer “interarts” intensive encompassing eight weeks of seminars and experiential encounters. This included live performances of theater and dance, numerous concerts, and diverse exhibitions of visual art.

“We got as far west as Cooperstown, New York, to the Glimmerglass Opera, the New York City Ballet at Saratoga, the Williamstown Theater for a few shows, some dance festivals around the area, and ended with our wonderful own Marlboro Music Festival right here,” Paul explained. As if that was not enough, the group stayed in London for another three weeks, following the same model.

Not at all coincidentally, one of Paul’s final courses in spring 2013, titled Happy Endings, was an exploration of ways in which different kinds of plays and films arrive at closure.

“Only Paul would choose to end his Marlboro career with a course on Happy Endings,” remarked Dana Howell, professor of cultural history. “The class offers his students—as always—his enormous range of knowledge of theater and film, along with his critical insights and his open-ended curiosity about new ways of telling a story through performance.”

His own closure at Marlboro is made much easier by the many retirement projects that await him at home.

“In many ways an academic life is a wonderful rehearsal period for retirement. I can look at it as if it is a very long sabbatical,” Paul quipped. “I will continue to conduct my London seminars, three of which I will lead in 2013, possibly four in 2014—interest among participants keeps growing. I have boxes full of research for two book projects, and a number of essays that I may return to.”

“Paul has contributed both breadth and depth to the whole college in several ways,” remarked Tim Little, retired history professor. “He sees the theater as a powerful force in the intellectual world, both to the performers and their supporters and to the audiences that observe them.”

Never at a loss for eloquent words, Paul waxed modest regarding his hopes for the future of theater at Marlboro.

“The best thing for me to do is leave it behind to allow others to reinvent theater at Marlboro in their own vision,” he stated. “We can create a program of excellence where theater, dance, film, music, and visual arts begin to see themselves not as isolated fields of study but as ‘liberal’ investigations of shared interests, creatively and continuously pursuing the joy and dignity of learning.” —Christian Lampart ’16