Cancer of the Birch Tree

By Elizaveta Mitrofanova ’15

Liza Mitrofanova explores the natural history and hopeful future of a fungus with roots in her Siberian homeland.

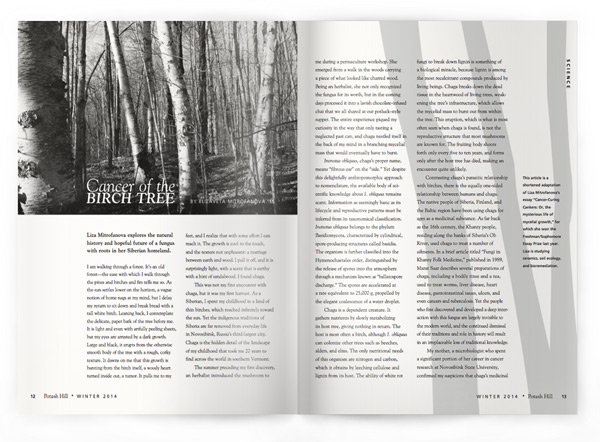

I am walking through a forest. It’s an old forest—the ease with which I walk through the pines and birches and firs tells me so. As the sun settles lower on the horizon, a vague notion of home nags at my mind, but I delay my return to sit down and break bread with a tall white birch. Leaning back, I contemplate the delicate, paper bark of the tree before me. It is light and even with artfully peeling sheets, but my eyes are arrested by a dark growth. Large and black, it erupts from the otherwise smooth body of the tree with a rough, corky texture. It dawns on me that this growth is bursting from the birch itself, a woody heart turned inside out, a tumor. It pulls me to my feet, and I realize that with some effort I can reach it. The growth is cool to the touch, and the texture not unpleasant: a marriage between earth and wood. I pull it off, and it is surprisingly light, with a scent that is earthy with a hint of sandalwood. I found chaga.

This was not my first encounter with chaga, but it was my first harvest. As a Siberian, I spent my childhood in a land of thin birches, which reached infinitely toward the sun. Yet the indigenous traditions of Siberia are far removed from everyday life

in Novosibirsk, Russia’s third-largest city. Chaga is the hidden detail of the landscape of my childhood that took me 20 years to find across the world in southern Vermont.

This was not my first encounter with chaga, but it was my first harvest. As a Siberian, I spent my childhood in a land of thin birches, which reached infinitely toward the sun. Yet the indigenous traditions of Siberia are far removed from everyday life

in Novosibirsk, Russia’s third-largest city. Chaga is the hidden detail of the landscape of my childhood that took me 20 years to find across the world in southern Vermont.

The summer preceding my first discovery, an herbalist introduced the mushroom to me during a permaculture workshop. She emerged from a walk in the woods carrying a piece of what looked like charred wood. Being an herbalist, she not only recognized the fungus for its worth, but in the coming days processed it into a lavish chocolate-infused chai that we all shared at our potluck-style supper. The entire experience piqued my curiosity in the way that only tasting a neglected past can, and chaga nestled itself in the back of my mind in a branching mycelial mass that would eventually have to burst.

Inonotus obliquus, chaga’s proper name, means “fibrous ear” on the “side.” Yet despite this delightfully anthropomorphic approach to nomenclature, the available body of scientific knowledge about I. obliquus remains scant. Information as seemingly basic as its lifecycle and reproductive patterns must be inferred from its taxonomical classification. Inonotus obliquus belongs to the phylum Basidiomycota, characterized by cylindrical, spore-producing structures called basidia. The organism is further classified into the Hymenochaetales order, distinguished by the release of spores into the atmosphere through a mechanism known as “ballistospore discharge.” The spores are accelerated at a rate equivalent to 25,000 g, propelled by the elegant coalescence of a water droplet.

Chaga is a dependent creature. It gathers nutrients by slowly metabolizing its host tree, giving nothing in return. The host is most often a birch, although I. obliquus can colonize other trees such as beeches, alders, and elms. The only nutritional needs of this organism are nitrogen and carbon, which it obtains by leeching cellulose and lignin from its host. The ability of white rot fungi to break down lignin is something of a biological miracle, because lignin is among the most recalcitrant compounds produced by living beings. Chaga breaks down the dead tissue in the heartwood of living trees, weakening the tree’s infrastructure, which allows the mycelial mass to burst out from within the tree. This eruption, which is what is most often seen when chaga is found, is not the reproductive structure that most mushrooms are known for. The fruiting body shoots forth only every five to ten years, and forms only after the host tree has died, making an encounter quite unlikely.

Contrasting chaga’s parasitic relationship with birches, there is the equally one-sided relationship between humans and chaga. The native people of Siberia, Finland, and the Baltic region have been using chaga for ages as a medicinal substance. As far back as the 16th century, the Khanty people, residing along the banks of Siberia’s Ob River, used chaga to treat a number of ailments. In a brief article titled “Fungi in Khanty Folk Medicine,” published in 1989, Marat Saar describes several preparations of chaga, including a bodily rinse and a tea, used to treat worms, liver disease, heart disease, gastrointestinal issues, ulcers, and even cancers and tuberculosis. Yet the people who first discovered and developed a deep interaction with this fungus are largely invisible to the modern world, and the continued dismissal of their traditions and role in history will result in an irreplaceable loss of traditional knowledge.

My mother, a microbiologist who spent a significant portion of her career in cancer research at Novosibirsk State University, confirmed my suspicions that chaga’s medicinal uses are not widely known in Russian society. To find out whether she is familiar with chaga’s traditional uses, I asked her what she knew about the mushroom. “I tried chaga tea once,” she said, “but I didn’t like the taste. I remember during the economic crisis (after the fall of the Soviet Union) there were shortages of tea, so some people brewed chaga. Birches aren’t subject to inflation like the ruble is.” My household did not shy away from traditional remedies, so my mother’s vague awareness of chaga’s existence reiterated the void I had encountered in formally researching the relationship between native culture and chaga.

Despite the gradual disappearance of folk knowledge, modern science is attempting

to take full advantage of chaga’s medicinal potential. There has been an influx of published research on chaga’s various medicinal properties, not the least of which is in the realm of cancer research. Using precise separation techniques, researchers have succeeded in isolating compounds from chaga in order to assess their effects on cancerous cells. The empirical data resulting from this research largely supports folk knowledge. Though a significant amount of research is available on various compounds isolated from chaga that exhibit cancer-fighting qualities, I will briefly describe only a handful of results. Chaga contains compounds that reduce cell mutation in the presence of specific mutagenic substances. Phenolic compounds isolated from chaga were found to have significant cytotoxic effects on cancer cells while causing minimal healthy cell death. Finally, certain polysaccharides from chaga have been correlated with improved immune response to cancerous cells. This is not to suggest that this fungus alone can cure cancers, but there is definitely enough evidence to explore the potential of using chaga extracts to supplement cancer therapy.

Despite the gradual disappearance of folk knowledge, modern science is attempting

to take full advantage of chaga’s medicinal potential. There has been an influx of published research on chaga’s various medicinal properties, not the least of which is in the realm of cancer research. Using precise separation techniques, researchers have succeeded in isolating compounds from chaga in order to assess their effects on cancerous cells. The empirical data resulting from this research largely supports folk knowledge. Though a significant amount of research is available on various compounds isolated from chaga that exhibit cancer-fighting qualities, I will briefly describe only a handful of results. Chaga contains compounds that reduce cell mutation in the presence of specific mutagenic substances. Phenolic compounds isolated from chaga were found to have significant cytotoxic effects on cancer cells while causing minimal healthy cell death. Finally, certain polysaccharides from chaga have been correlated with improved immune response to cancerous cells. This is not to suggest that this fungus alone can cure cancers, but there is definitely enough evidence to explore the potential of using chaga extracts to supplement cancer therapy.

In contemplation of the obscure nature of chaga and the inaccessible nature of scientific research, I wondered how tales of chaga could have found their way to southern Vermont. I found one possible answer in an unexpected place: a chapter of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novel The Cancer Ward, entitled “Cancer of the Birch Tree.” The protagonist of the novel is a political prisoner who discovers he has cancer and upon release is exiled and sent to a hospital in one of the Soviet satellite states. In this chapter, he tells the other patients about a practitioner in Russia who discovers that the country-folk in his region brew chaga to treat tumors. The prisoner feels a deep and bitter nostalgia for his home and a resentment at being deprived of something that could have potentially served as a cure for his and the other patients’ diseases. “People living in that country do not always understand their motherland, they want bright blue seas and bananas, but there’s the thing, so necessary to man: a black, ugly growth on a little white birch, her disease, her cancer.” There is a sense of painful irony in the collision between one species’ cure and another species’ illness, and Solzhenitsyn brings that tension to the forefront in this chapter.

Past the windowsill where the chaga I harvested lies undisturbed, my window looks into a sea of trees. Beeches, beeches, beeches, a dash of maple, some ash, endless young beeches, and yes, birches. I remember how ominous and mysterious that dark conk seemed, protruding from the white birch that kept me company on that autumn day. Chaga has lost none of its mystery since then, and in fact, it has only brought more: it has come to symbolize a forgotten and overlooked people.

The time has come for me to taste the fruits of chance and labor and prepare my own elixir. I hope that, somehow, in going through the same motions that the Khanty did, I will embody the type of understanding that evaded me as I sifted through scientific and anthropological texts. I use a pocketknife to cut a small portion of the chaga into thin shavings, increasing surface area for a more thorough extraction. I think of the inhuman patience of scientists, building an art out of precision to prove to the world that ancient wisdom is still relevant. Mine is a clunky, graceless process done in the stale air of a shared kitchen.

The pot I use is an ancient piece of junk from Siberia, typically used to prepare Turkish coffee. Watching as the chaga shavings trace convection currents in the simmering water, I can’t shake the sensation of cold, twisting anxiety building in my stomach. Will my simple process really make this dark fungus fit for consumption? A steaming cup of chaga tea is poured, and after a brief pause, the hard rim of the mug is at my lips. The taste is surprisingly mild, like watered-down English Breakfast tea with wooden hints of earth. The hot liquid spells relief as it heats my core and stretches through the fibers of my body to arrive in bursts of warmth at my extremities, finally, setting my nervous mind at ease.

This article is a shortened adaptation of Liza Mitrofanova’s essay “Cancer-Curing Cankers: Or, the mysterious life of mycelial growth,” for which she won the Freshman/Sophomore essay Prize last year. Liza is studying ceramics, soil ecology, and bioremediation.

Extracting anticancer compounds

Senior Daniel Zagal has been exploring the medicinal properties of plants in the lab, starting

with a tutorial last year extracting compounds from hops and testing their anticancer activity.

“The results were exciting and positive,” said Daniel. “More than one fraction inhibited the

growth of cervical cancer cells and even killed some of them.” He went on to a summer intern

ship at university of Illinois at Chicago, where he helped develop a new method for the isolation

of glabridin, a compound found in licorice with promising medicinal properties. His Plan of Concentration involves extracting compounds from stinging nettle, and testing them for anticancer and other pharmacological and biological activities. “Nettle was the first plant to be studied under a microscope, so it appealed to me as an interesting classic in science,” said Daniel.

Senior Daniel Zagal has been exploring the medicinal properties of plants in the lab, starting

with a tutorial last year extracting compounds from hops and testing their anticancer activity.

“The results were exciting and positive,” said Daniel. “More than one fraction inhibited the

growth of cervical cancer cells and even killed some of them.” He went on to a summer intern

ship at university of Illinois at Chicago, where he helped develop a new method for the isolation

of glabridin, a compound found in licorice with promising medicinal properties. His Plan of Concentration involves extracting compounds from stinging nettle, and testing them for anticancer and other pharmacological and biological activities. “Nettle was the first plant to be studied under a microscope, so it appealed to me as an interesting classic in science,” said Daniel.