When the Earth Speaks

By Catherine O’Callahan

When Marlboro faculty and students traveled to Nepal last April to explore the embodiment of religious experience, they had no idea that many of the religious and cultural sites they visited would be destroyed by a devastating earthquake days later, not to mention the human loss. What they learned about was much more than religious diversity, but the unity of all humanity.

In anticipation of our first class following the devastating earthquake that struck Nepal on April 25, 2015, I carefully scribed the Buddha’s last words on the chalkboard:

Impermanent are all formations. Observe this carefully, constantly.

The students and faculty in our class—called Embodying Diversity: Religious Communities and Practices in Nepal—had arrived back on Potash Hill only two weeks earlier. Supported by Marlboro’s Gannett grant for international travel and Aron grant for faculty and student collaboration, we had travelled to Nepal for two and a half weeks over spring break. Our class focused on religious diversity in Nepal, and in Kathmandu we were able to experience the rhythm and flow of religious life—Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian—firsthand.

Nepal is an ideal site to study religious diversity because it is a crossroads of many traditions, and on site we were able to explore how religious worlds are constructed as well as how people move through these worlds. Yet we had no idea how much that experience would change us, and how much Nepal would change soon after we left.

As is typical for Americans studying religion in other cultures, it came as a shock to most of the students that religious life was not relegated to a separate, hidden, or private sphere. Wandering the streets of Boudhanath, named for a giant, sacred stupa in central Kathmandu, we found butter lamps burning bright and ordinary people busy with their prostrations. As we meandered through the great Shiva temple, Pashupatinath, the flames emanating from the newly dead and the tears of the bereaved mingled under a bright sun.

“In America, religion is much less out in the open,” said Blake Stanyon, a Marlboro sophomore who was researching the lasting effects on Nepal society of the monarchy, which was abolished in 2008. “We all get offended if somebody we don’t share the same faith with acts too religious around us. In Nepal, shrines are all around, and sometimes Hindu and Buddhist sites mix. It is everywhere, and people accept it as part of life, just as much as we accept advertising.”

As described by Marlboro politics professor Lynette Rummel, who joined our trip, “Participating in puja, doing kora, witnessing all sorts of festivals, rituals, and the daily practices and processions involving prayer wheels, prayer flags, and alms giving…this is the richness of life in Nepal, where religion is not separate from the everyday, and Hindus and Buddhists and all shades of mixtures in between surround you from morning until night, and indeed into the night itself.”

“People there are dedicated to their worship, but it just looks like a part of their lives,” said senior Jennifer Dudley, who was researching attitudes toward the body in Nepal, specifically the significance of prostrations in Buddhist practice. “Religion seems to permeate their culture in a way it doesn’t here, but I never felt that their religion was being imposed on me, the way I often do in the States.”

Our class premise had been that the body is central to the experience and expression of religious life, and we had many experiences in Nepal that reinforced that. On a pilgrimage to Namo Buddha monastery in the foothills of the Himalayas, our Tibetan friends taught us how to perform prostrations before the image of Shakyamuni Buddha. We had tried to practice these a bit in class, with the assumption that they are something to be learned. But only through repetitive practice could we know the joy of the full body reaching up, collecting at the head, throat, and heart, and lastly prone on the sweet earth. This pilgrimage site celebrates the Buddha’s sacrifice of his own flesh to save a starving mother tigress and her cubs, and images of the Buddha cutting his own body with a knife adorn the high paths.

At the sacred Hindu temple of Pashupatinath, we wandered along the banks of the Bagmati River, saw ash-covered Shaivites, hermit dwellings, and the hospice right beside the river. A number of newly dead were carried down the stairs of the hospice to be purified in the river and then laid on the ghats for cremation. Nothing was hidden, and everything was happening simultaneously: children begging us for money, relatives weeping for their dead, women doing laundry, children fishing, and music wafting through the smoky places. High above the river we were able to see rows of Shiva lingams, simple representations of the Hindu deity that are among the oldest religious symbols, reverberating in a line that seemed never to end.

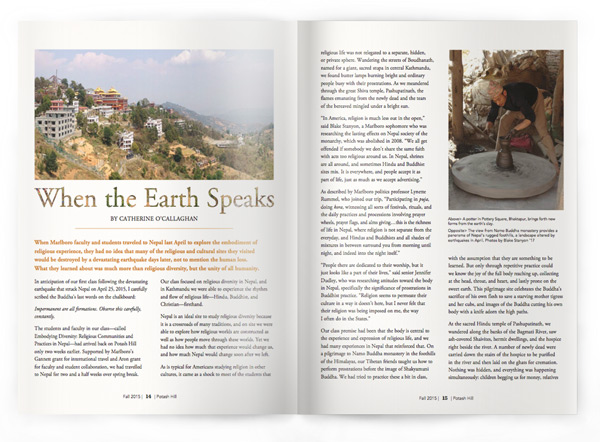

When we visited Bhaktapur, an ancient Newar city known as Place of Devotees, with its labyrinthine alleys and tremendous South Indian temple architecture, we marveled at images from the Kama Sutra exquisitely carved into the Krishna temple. We were blessed with tikka head jewelry in the house of the Kumari, one of Nepal’s living goddesses. Around corners we saw women gathered by wells, bringing up water from the deep, and our guide pointed out a group of wailing women, saying that someone had just died at home. The potter’s square, full now with piggy banks for the tourist trade, was hot in the sun. Women bent over pots, setting them down ever so carefully. The clay—thought to be auspicious—emerges from the earth.

Exploring another strand in the complex weave of religious practice in Nepal, Marlboro junior Jonah Nonomaque collaborated with Lynette Rummel on research regarding conversion to Protestantism. “Very little research has been done on the growth of Christianity in Nepal, so I was eager to help fill this void while applying, testing, and enriching my own theoretical insights,” said Jonah, who has also studied Protestant conversion in upland Southeast Asia. “As an aspiring anthropologist, I found the opportunity to engage in fieldwork highly rewarding and challenging.”

Jonah and Lynette attended an evangelical church service that seemed to have no discernible beginning or end, and Lynette was even summoned to the pulpit by the pastor to give a short speech (including a “shout-out” to Marlboro College). The video presentation they made based on their experiences displayed worshippers slain in the spirit, a laying on of hands, a shaking body, and finally a worshipper in repose. The extreme physicality of the expression did not seem out of place among all we had seen so far in Kathmandu.

We ascended the steps to the great Stupa of Svayambhu and explored a world where Buddhist and Hindu expression coexist and mutually celebrate each other. At the threshold of the shrine, with our students huddled round, Buddhist studies scholar Hubert Decleer retold the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment and how the very earth rose as witness. The Buddha’s classic pose— fingers touching the ground—evoked the earth goddess herself. As we entered the cavernous shrine to the earth goddess Vasudhara, vermillion powder flashing red on the well-rubbed deities among the flickering butter lamps, the earth—the home, the source, the wellspring, and the grave—was never more alive to me.

Later in April the earth rose as witness once more. When the catastrophic earthquake struck Nepal, leaving over 9,000 dead, 23,000 injured, thousands homeless, and many UNESCO world heritage sites in ruins, I recited the Buddha’s last words to my class: “Impermanent are all formations. Observe this carefully, constantly.” I told the students that it was a practice of mine to memorize important texts, in the event that the paper, the stone, even the temples they are inscribed upon disappear. As, indeed, they will.

We shared our feelings of shock and helplessness in the wake of the disaster, the deadliest earthquake to hit Nepal on record. New friends did not turn up on Facebook; familiar sacred places had fallen; a country, whose weak infrastructure and poverty had been so evident to us, was now in crisis. I reminded the class of our first readings of the semester: the Bhagavad Gita. Many had wrestled with the text, the apparent fatalism of Krishna’s instructions to Arjuna, and Arjuna’s confusion.

I am weighed down by pity, Krishna; my mind is utterly confused. Tell me where my duty lies, which path I should take.

I ventured to suggest that Arjuna’s quandary was now ours: what is the correct response to such a vision, to such a horrific event, when the earth speaks with such violence? When Krishna reveals the universal form, Arjuna, although overwhelmed, resolves to perform his duty.

Arjuna saw the whole

Universe

Enfolded, with its countless

Billions

Of life-forms, gathered

Together

In the body of the God of gods.

Our students rallied, and held two auctions to raise funds to support earthquake relief efforts. Students donated items they had bought in Kathmandu and wonderful works from Marlboro’s many artists. We gave to the Earthquake Relief Fund at Shechen Monastery, because we had stayed in their guesthouse; we also contributed to Himalayan Roots to Fruits, who were our Tibetan “buddies,” as well as SEBS North America Nepal. Altogether the Marlboro community— students, alumni, staff, faculty, and trustees—mobilized to raise over $10,000 to send to Nepal.

“The money we raised is insignificant in the grand picture of things, but it is not insignificant: for we have been touched, and now we care deeply and personally,” said Lynette. “Events in Nepal are no longer just a story in the news. They are part of our lives. And while our efforts pale in comparison to the task of the rebuilding that lies ahead, what we have learned has made us more compassionate, more empathetic, more human.”

Our investigation of religious diversity, and our trip to Nepal in particular, taught us that no matter how far away and exotic other cultures are, we are all part of the same earth. And when the earth speaks, we will ask with Arjuna:

Teach me the way of worship

What it is, here, in the body.

Catherine O’Callaghan is assistant dean of academic advising at Marlboro College. She has a master of theological studies (MTS) in biblical studies from the Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a BA in English and theology from Fordham University.

Embodying Unchurched Spirituality

Far from the crowded streets of Kathmandu, but with a similar purpose, Alex Bobella ’15 explored the importance of movement in spiritual belief for his Plan in religion and dance. He was specifically interested in religious beliefs existing outside of organized religion, loosely categorized as “unchurched” spirituality, and the work of contemporary artist Deborah Hay, whose choreography features a “focused inquiry into bodiliness.” “The body, according to Hay, is capable of forms and understandings that the conscious mind is not,” says Alex, who presented a Plan performance titled “A Catalogue of Non-Definitive Acts.” “Ever-present and constantly interpreting amorphous reality, while the analytical mind is caught in worry, the body surpasses the cognitive mind in contextualizing the self within the world. The body is a vessel for spiritual experience that celebrates a fundamental human quality—movement—and can be used in service of creating peak, almost transcendent, experiences.”

Far from the crowded streets of Kathmandu, but with a similar purpose, Alex Bobella ’15 explored the importance of movement in spiritual belief for his Plan in religion and dance. He was specifically interested in religious beliefs existing outside of organized religion, loosely categorized as “unchurched” spirituality, and the work of contemporary artist Deborah Hay, whose choreography features a “focused inquiry into bodiliness.” “The body, according to Hay, is capable of forms and understandings that the conscious mind is not,” says Alex, who presented a Plan performance titled “A Catalogue of Non-Definitive Acts.” “Ever-present and constantly interpreting amorphous reality, while the analytical mind is caught in worry, the body surpasses the cognitive mind in contextualizing the self within the world. The body is a vessel for spiritual experience that celebrates a fundamental human quality—movement—and can be used in service of creating peak, almost transcendent, experiences.”