Only Women Will Heal Me

Photos and Story by Brad Heck ’04 and Willow O’Feral ‘07

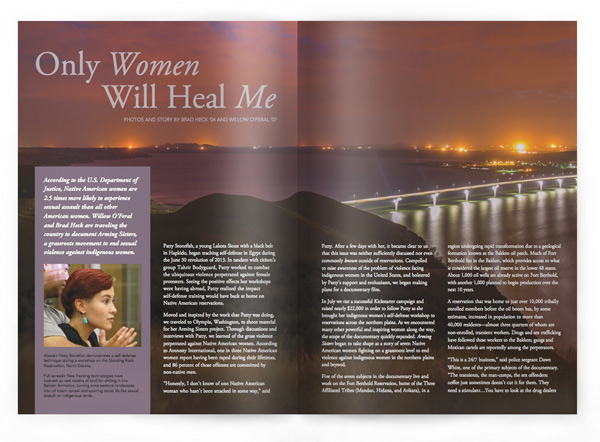

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Native American women are 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual assault than all other American women. Willow O’Feral and Brad Heck are traveling the country to document Arming Sisters, a grassroots movement to end sexual violence against indigenous women.

Patty Stonefish, a young Lakota Sioux with a black belt in Hapkido, began teaching self-defense in Egypt during the June 30 revolution of 2013. In tandem with citizen’s group Tahrir Bodyguard, Patty worked to combat the ubiquitous violence perpetrated against female protesters. Seeing the positive effects her workshops were having abroad, Patty realized the impact self-defense training would have back at home on Native American reservations.

Moved and inspired by the work that Patty was doing, we traveled to Olympia, Washington, to shoot material for her Arming Sisters project. Through discussions and interviews with Patty, we learned of the gross violence perpetrated against Native American women. According to Amnesty International, one in three Native American women report having been raped during their lifetimes, and 86 percent of those offenses are committed by non-native men.

“Honestly, I don’t know of one Native American woman who hasn’t been attacked in some way,” said Patty. After a few days with her, it became clear to us that this issue was neither sufficiently discussed nor even commonly known outside of reservations. Compelled to raise awareness of the problem of violence facing indigenous women in the United States, and bolstered by Patty’s support and enthusiasm, we began making plans for a documentary film.

In July we ran a successful Kickstarter campaign and raised nearly $22,000 in order to follow Patty as she brought her indigenous women’s self-defense workshop to reservations across the northern plains. As we encountered many other powerful and inspiring women along the way, the scope of the documentary quickly expanded. Arming Sisters began to take shape as a story of seven Native American women fighting on a grassroots level to end violence against indigenous women in the northern plains and beyond.

Five of the seven subjects in the documentary live and work on the Fort Berthold Reservation, home of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara), in a region undergoing rapid transformation due to a geological formation known as the Bakken oil patch. Much of Fort Berthold lies in the Bakken, which provides access to what is considered the largest oil reserve in the lower 48 states. About 1,000 oil wells are already active on Fort Berthold, with another 1,000 planned to begin production over the next 10 years.

A reservation that was home to just over 10,000 tribally enrolled members before the oil boom has, by some estimates, increased in population to more than 40,000 residents—almost three quarters of whom are non-enrolled, transient workers. Drugs and sex trafficking have followed these workers to the Bakken; gangs and Mexican cartels are reportedly among the perpetrators.

“This is a 24/7 business,” said police sergeant Dawn White, one of the primary subjects of the documentary. “The transients, the man-camps, the sex offenders: coffee just sometimes doesn’t cut it for them. They need a stimulant…You have to look at the drug dealers as business men…they’re going where the money’s at, and the money’s right here.”

Dawn is a pillar within the Fort Berthold community, one of the first women to receive the Champions of Public Safety in Indian Country Award (June 2014). We spent several nights riding along with Dawn as she patrolled the reservation. Dawn’s approach to her job requires a difficult balance of holding community members responsible for their actions while at the same time not taking their infractions personally and forgiving them the following day. There were few members she stopped whom she did not know by name, and many were related to her.

Dawn is also a survivor of sexual assault. Before becoming a police officer she was enrolled in the military, and while stationed in Germany she was sexually assaulted by another soldier. The trauma will “always be with me,” said Dawn. “It will never go away.” She described how the experience informs her work: “It does carry over to the job…being a survivor of [sexual assault] I know what that fear is, I know how it grips you…and it has helped, because I want to catch this person for them, I want to bring them to justice.”

Bringing perpetrators of sexual assault to justice is difficult on a reservation, especially when the assailant is a non-enrolled member. The semi-sovereign state of Indian reservations requires coordination between tribal, state, and federal government agencies during investigations, and often in the case of a non-enrolled assailant, the burden of prosecution lies with the federal government. This results in a lot of jurisdictional pitfalls, and many cases get dropped before they ever come to trial. According the The Atlantic magazine, “In 2011, the U.S. Justice Department did not prosecute 65 percent of rape cases reported on reservations.”

Chalsey Snyder, an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes and another subject of the documentary, is working to increase the jurisdictional power of the Fort Berthold tribal government in cases of sex trafficking. She is writing tribal code that broadens the legal definition of sex trafficking and nearly triples the penalties and fines the Three Affiliated Tribes may enforce. She has named the tribal code “Loren’s Law” in honor of her friend and co-author of the code, who died tragically in a car accident last year.

Arming Sisters also focuses on Loreline LaCroix, a freelance advocate working with victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and sex trafficking. Although she has extensive experience in advocacy, she prefers being outside of the system, working one-on-one with her clients. Comprising one million acres, Fort Berthold is vast, and social services are seriously understaffed; sometimes Loreline is informally commissioned by tribal police officers and advocates to help handle the overflow of victims.

Loreline has a long and traumatic history with assault herself, including being abused at age 2, molested at age 9, raped at age 12, and hospitalized by her first boyfriend and father of her oldest son at age 18. She has been in a stable and healthy marriage for the last 15 years, and views her work with other survivors as a form of restoration.

“I love what I do,” said Loreline. “I’m passionate about working with women…and only women will heal me. This work heals me. And I’ve got a lot of healing to do, so I have a lot of women to help.”

The pervasive violence against Native American women in this country, as witnessed by the subjects of Arming Sisters, is intolerable—yet it has become normalized. The primary goal of the documentary is to raise awareness of the issue and humanize the statistics by sharing the stories of survivors who are actively fighting for positive change. As explained by Lisa Brunner, an advocate for survivors and also one of the subjects of the film, “The first step is for it to be discussed at dinner tables across this country.”

Willow O’Feral and Brad Heck are currently working on editing and raising funds for post-production of Arming Sisters, and they extend their thanks to the Marlboro community for its ongoing support. For more information or to support the film, please visit: www.armingsistersmovie.com.

Direct cinema in a New Jersey free school

Documentary films bring social issues to life, and for the first feature film of Amanda Wilder ’07 that issue is alternative education. “From the first day at Teddy McArdle Free School I could tell it would be an incredible thing to document, and would fit nicely with the kind of direct cinema I’d grown to love,” says Amanda. “There was a story unfolding before the camera, and a fascinating group of people, most of whom were children.” The resulting film, Approaching the Elephant, poses the vital question of how kids and adults learn to sort things out and live with each other in a school where the youngest student and the school’s director have equal say. In January, Amanda screened Approaching the Elephant at the Latchis Theater, in Brattleboro, and participated in a panel discussion with producer and film professor Jay Craven in New York City.

Documentary films bring social issues to life, and for the first feature film of Amanda Wilder ’07 that issue is alternative education. “From the first day at Teddy McArdle Free School I could tell it would be an incredible thing to document, and would fit nicely with the kind of direct cinema I’d grown to love,” says Amanda. “There was a story unfolding before the camera, and a fascinating group of people, most of whom were children.” The resulting film, Approaching the Elephant, poses the vital question of how kids and adults learn to sort things out and live with each other in a school where the youngest student and the school’s director have equal say. In January, Amanda screened Approaching the Elephant at the Latchis Theater, in Brattleboro, and participated in a panel discussion with producer and film professor Jay Craven in New York City.