Good Fortune Next Time

By Will Wootton ’72

“In my world, Sisyphus would be a mid-level manager,” says Will Wootton, Marlboro College’s former vice president of institutional advancement, in his upcoming memoir. “Outside the classroom, all [colleges and universities] face nearly identical fiscal, political, and philosophical institutional challenges, and they face them over and over, by year, by decade, by president.” In this excerpt, Will describes one of the years Marlboro skirted disaster.

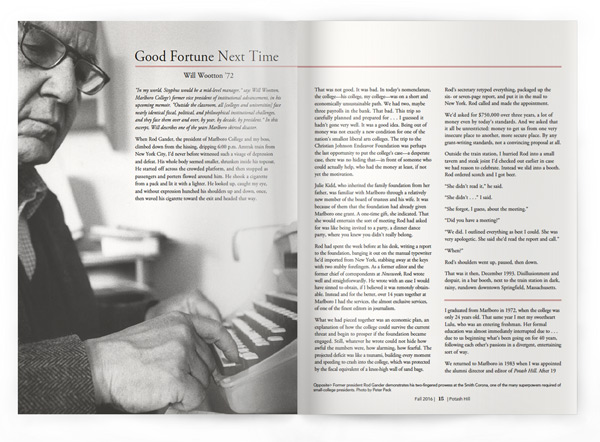

When Rod Gander, the president of Marlboro College and my boss, climbed down from the hissing, dripping 6:00 p.m. Amtrak train from New York City, I’d never before witnessed such a visage of depression and defeat. His whole body seemed smaller, shrunken inside his topcoat. He started off across the crowded platform, and then stopped as passengers and porters flowed around him. He shook a cigarette from a pack and lit it with a lighter. He looked up, caught my eye, and without expression hunched his shoulders up and down, once, then waved his cigarette toward the exit and headed that way.

That was not good. It was bad. In today’s nomenclature, the college—his college, my college—was on a short and economically unsustainable path. We had two, maybe three payrolls in the bank. That bad. This trip so carefully planned and prepared for . . . I guessed it hadn’t gone very well. It was a good idea. Being out of money was not exactly a new condition for one of the nation’s smallest liberal arts colleges. The trip to the Christian Johnson Endeavor Foundation was perhaps the last opportunity to put the college’s case—a desperate case, there was no hiding that—in front of someone who could actually help, who had the money at least, if not yet the motivation.

Julie Kidd, who inherited the family foundation from her father, was familiar with Marlboro through a relatively new member of the board of trustees and his wife. It was because of them that the foundation had already given Marlboro one grant. A one-time gift, she indicated. That she would entertain the sort of meeting Rod had asked for was like being invited to a party, a dinner dance party, where you knew you didn’t really belong.

Rod had spent the week before at his desk, writing a report to the foundation, banging it out on the manual typewriter he’d imported from New York, stabbing away at the keys with two stubby forefingers. As a former editor and the former chief of correspondents at Newsweek, Rod wrote well and straightforwardly. He wrote with an ease I would have sinned to obtain, if I believed it was remotely obtainable. Instead and for the better, over 14 years together at Marlboro I had the services, the almost exclusive services, of one of the finest editors in journalism.

What we had pieced together was an economic plan, an explanation of how the college could survive the current threat and begin to prosper if the foundation became engaged. Still, whatever he wrote could not hide how awful the numbers were, how alarming, how fearful. The projected deficit was like a tsunami, building every moment and speeding to crash into the college, which was protected by the fiscal equivalent of a knee-high wall of sand bags.

Rod’s secretary retyped everything, packaged up the six- or seven-page report, and put it in the mail to New York. Rod called and made the appointment.

We’d asked for $750,000 over three years, a lot of money even by today’s standards. And we asked that it all be unrestricted: money to get us from one very insecure place to another, more secure place. By any grant-writing standards, not a convincing proposal at all.

Outside the train station, I hurried Rod into a small tavern and steak joint I’d checked out earlier in case we had reason to celebrate. Instead we slid into a booth. Rod ordered scotch and I got beer.

“She didn’t read it,” he said.

“She didn’t . . .” I said.

“She forgot, I guess, about the meeting.”

“Did you have a meeting?”

“We did. I outlined everything as best I could. She was very apologetic. She said she’d read the report and call.”

“When?” Rod’s shoulders went up, paused, then down.

That was it then, December 1993. Disillusionment and despair, in a bar booth, next to the train station in dark, rainy, rundown downtown Springfield, Massachusetts.

***

I graduated from Marlboro in 1972, when the college was only 24 years old. That same year I met my sweetheart Lulu, who was an entering freshman. Her formal education was almost immediately interrupted due to . . . due to us beginning what’s been going on for 40 years, following each other’s passions in a divergent, entertaining sort of way.

We returned to Marlboro in 1983 when I was appointed the alumni director and editor of Potash Hill. After 19 years there I was vice president of institutional advancement and Marlboro had grown from a perilously low 167 students to just over 300.

Among independent colleges and universities, there are financially shaky ones: old, settled in their ways, and constantly aging badly. There are colleges newly born, others approaching adolescence, and still others finally nearing something like adulthood after 70 or 80 years of hard living. There are huge 20,000-student universities, and colleges with thousands of undergraduates, and finally there are tiny places like Marlboro, shrews dodging the footfalls of dinosaurs.

Marlboro and Sterling College in northern Vermont, where I served as president from 2006 to 2012 and where there are just over 100 students, are distinguished not only by their size but also by their unusual curricula, their history, place, and people. It hardly matters, in one sense, because in the context of American higher education each is unknown, underendowed, underfunded, and, worst of all, practically unimaginable to the general college aspirant: a whole college considerably smaller than your high school graduating class. How could that be?

Each is further notable for having more than once skirted dangerously close to the sheer cliff edge of institutional oblivion. Today both remain small, so tiny that anyone who claims to know anything about higher education—and there are millions who do—would predict their near-immediate demise with an air of complete assurance, simply because of their obscurity and ridiculous, uneconomical, and clearly unsustainable size.

Marlboro (somewhat erratically) and Sterling (somewhat compulsively) have spent a lot of their time figuring out how to stay small, how not to grow. They understand, as do some other Vermont colleges, that the diseconomy of scale is not the primary threat; that there are other, equally forbidding threats out there, including fiscal mismanagement, legal claims, lack of critical resources, shortfalls in admissions, board dysfunction, inept leadership, and increases in regulatory burden coinciding with any of the above. If it were as simple as being small, they all would have succumbed decades ago, and this memoir would not exist.

Among the couple thousand independent liberal arts colleges, the Ivies and the potted Ivies are cushioned by enormous endowments and their own gold-plated histories, shaped from studiously cultivated alumni, their alumni parents, and alumni children. There must be another thousand regional institutions, including faith-based colleges and universities, that are fiscally and institutionally sound and have been for generations.

Death and its dismissive cousin, death-by-merger, is reserved for the old and infirm, the shrinking, the undernourished, the timid, and for the young, the experimental, and specialized. To this segment of the industry, death visits quite often, especially in New England, where the college-going population has been in decline off and on for 20 years, while the competition from state institutions and for-profit colleges has surged.

In Vermont, Windham College succumbed in the early ’80s, as did the fledgling Mark Hopkins College before the decade was out, then Trinity in 2000, and Woodbury in 2008; in Massachusetts, Atlantic Union College closed in 2011 and Urban College of Boston in 2012; and in 2012 New Hampshire’s Chester College went under. Famously, Antioch, in Ohio, succumbed after more than a century (it reopened after some years, unaccredited and struggling). Recently Sweet Briar announced its closure, but the alumni rescued it, at least for the short term, and Burlington College closed its doors just this year.

For me, there’s a critical aspect to endemic institutional fragility: that for some of us, in some perverse way, it is the odds against a future that makes it all worthwhile, that justifies spending one’s effective working years at worthy places that, to express it gently, are not assured the level of stability enjoyed by their wealthier and better known partners in the higher education world.

***

Rod came into my office at Marlboro, down the hall from his, and plopped into the red, as opposed to green, chair. It had been days since we drove back from Springfield to Vermont and began waiting for Julie Kidd to call.

I was typing a story for the alumni magazine, Potash Hill. I didn’t turn around.

“She called.” I stopped typing.

“She read it. She’s going to do the whole thing: $250,000 a year for three years. Unrestricted.”

The tsunami disappeared like fog does, like it was never seriously there. I turned around and saw Rod practically floating from the weight off his shoulders. He was grinning. He started to sing, holding up his palms—he knew the words to hundreds of tunes, from the ’20s to the mid-’50s: “We’re in the money / The sky is sunny / Old man depression, you are through.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s great. But what have you done today to save the place?”

“Not a thing,” he said. “I’m waiting for tomorrow when I tell the board we’re halfway to a balanced budget. And it’s only November. It reminds me of the newspaper hawker in Chicago. We’ll have to send him to another corner.”

“What hawker?”

“Whatever the headlines were, he stuck with only one call, over and over, for years: ‘Many Dead, Many Dying! Many Dead, Many Dying!’”

Will Wootton retired in 2012 after serving as president of Sterling College for six years, when he “ran out of things to do, stuff to fix, nearby streams to fish.” This article is excerpted and adapted from Will’s memoir, Good Fortune Next Time: Life, Death, Irony, and the Administration of Very Small Colleges, due to be released by Dryad Press in fall 2017. The same chapter in full, titled “Many Dead, Many Dying,” was previously excerpted in Santa Fe Writer’s Project Quarterly Issue 5, Spring 2016.