“Our Heart Divides in Two”: Bifocality in the Experience of Brazilian Migrants

Story & photos by Sasha Iammarino ’16

Story & photos by Sasha Iammarino ’16

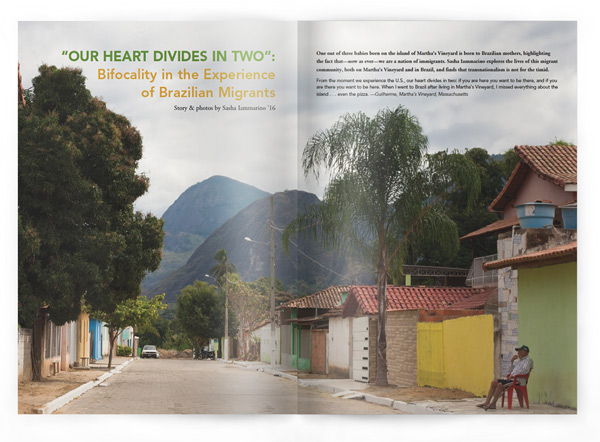

One out of three babies born on the island of Martha’s Vineyard is born to Brazilian mothers, highlighting the fact that—now as ever—we are a nation of immigrants. Sasha Iammarino explores the lives of this migrant community, both on Martha’s Vineyard and in Brazil, and finds that transnationalism is not for the timid.

“From the moment we experience the U.S., our heart divides in two: if you are here you want to be there, and if you are there you want to be here. When I went to Brazil after living in Martha’s Vineyard, I missed everything about the island . . . even the pizza.”

—Guilherme, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

Beginning in the latter part of the 1980s, a small-scale migration emerged from within the Brazilian towns of Mantenópolis and Cuparaque, near the city of Governador Valadares, to one location in the United States: Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Although the influence of this migration is apparent in the large houses and businesses built by migrants in both Brazilian towns, there are few sources of information about how these migrants became incorporated into Martha’s Vineyard while remaining active in the towns they come from. The changed lives of these mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses, as they are called, are embedded in the individual stories of the people who migrated, their families, and their friends.

Beginning in the latter part of the 1980s, a small-scale migration emerged from within the Brazilian towns of Mantenópolis and Cuparaque, near the city of Governador Valadares, to one location in the United States: Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Although the influence of this migration is apparent in the large houses and businesses built by migrants in both Brazilian towns, there are few sources of information about how these migrants became incorporated into Martha’s Vineyard while remaining active in the towns they come from. The changed lives of these mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses, as they are called, are embedded in the individual stories of the people who migrated, their families, and their friends.

As part of my Plan of Concentration research, I conducted surveys and interviews with Brazilian migrants who live on Martha’s Vineyard, as well as those who have returned to Brazil after living on the island. I conducted all of the interviews in Portuguese and translated them into English myself. The voices of the people I interviewed best articulate the difficulty migrants face as they attempt to improve their lives and the ways they negotiate their experiences both in their place of origin and on Martha’s Vineyard.

It is really difficult, because our family stays there [Mantenópolis]. His father is there, my mother, my two uncles, and other relatives. Our family weighs on our desire to return to Brazil… It is easier for my children to return to Brazil and then come back here. I want to send them there to visit Brazil.

It is really difficult, because our family stays there [Mantenópolis]. His father is there, my mother, my two uncles, and other relatives. Our family weighs on our desire to return to Brazil… It is easier for my children to return to Brazil and then come back here. I want to send them there to visit Brazil.

–Júlia, 26 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

The majority of Brazilians that go to the island in the work season go thinking about how much they can save, so they return. We were not like that. We wanted a stable life there. But the money that we ended up saving up, after being there for a while, we started investing in Mantenópolis…. We were born here, we grew up here, we are familiar with here, so we came here. We returned to Mantenópolis.

–Marlene, 45 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

It is a cultural story…. So many Americans that go to Brazil want to live there. So why can’t we do the same here? I know people from my town [Mantenópolis] that are married to Americans, have a family here [Martha’s Vineyard], have children, the husband already speaks Portuguese, or vice versa, the American wife learns Portuguese. So there is this mixture. This migration is renewing itself, the culture of the country… there is that thing going on here—how do you say it—the intermixing of culture.

It is a cultural story…. So many Americans that go to Brazil want to live there. So why can’t we do the same here? I know people from my town [Mantenópolis] that are married to Americans, have a family here [Martha’s Vineyard], have children, the husband already speaks Portuguese, or vice versa, the American wife learns Portuguese. So there is this mixture. This migration is renewing itself, the culture of the country… there is that thing going on here—how do you say it—the intermixing of culture.

–Guilherme, 36 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

I wanted to go back to Brazil because of my family. I also worked too much, and it got to the point where I was too tired…. My experience there was good, but if we didn’t have to work so much… There are a lot of people who say that Brazilians are made into slaves once they are in the U.S., but the reality is that we make ourselves into slaves when we are here. Because we want to return soon, and the more we work the faster we will return.

–Victória, 45 years old, lives in Cuparaque

I don’t want to leave here; I really like it here. It is tranquil. The life of my children is good because I have peace here. I have the peace to sleep with my front door unlocked the whole night. Things are changing, but compared to other places this is paradise. In Mantenópolis it is much more difficult… because people still struggle there a lot in general. And unfortunately Mantenópolis is really violent, there is a lack of security, a lack of order, so it is still pretty bad there. I enjoy traveling there because our family is there. But I prefer to live here.

I don’t want to leave here; I really like it here. It is tranquil. The life of my children is good because I have peace here. I have the peace to sleep with my front door unlocked the whole night. Things are changing, but compared to other places this is paradise. In Mantenópolis it is much more difficult… because people still struggle there a lot in general. And unfortunately Mantenópolis is really violent, there is a lack of security, a lack of order, so it is still pretty bad there. I enjoy traveling there because our family is there. But I prefer to live here.

–Carla, 34 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

The decision to leave is much more difficult than to come here. Especially after we have children. Unfortunately, our country’s culture is sad…. Of course it’s not everyone in Brazil… but unfortunately the majority of people are complicated…. And ours [our family] say in Brazil: Don’t come back because you miss us, stay there in the U.S., the situation in Brazil is not good. So our relatives also weigh on our decision to stay here.

–Júlia, 28 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

There are many Brazilians who come here and don’t ever go back [to Brazil]. There is Zezinho, who has been here for 12 years and does not plan on returning. There is my wife’s cousin who works with me, who has been here for a long time, and he wants to build a house on Martha’s Vineyard. Many Brazilian migrants here are like that… Sometimes there are some who want to return to Brazil, that arrive tired, and tire themselves out by working, and they want to return.

–Eliton, 34 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

We grew up here [Martha’s Vineyard]…and this is like our life. You know? So I don’t know if people can get used to Brazil anymore… because life in Brazil is so different from here; it’s much more difficult… Here we work, travel, you can go to a store and buy what you want…. It’s one thing for you to visit Brazil, but it’s a completely different thing to live there, understand?

We grew up here [Martha’s Vineyard]…and this is like our life. You know? So I don’t know if people can get used to Brazil anymore… because life in Brazil is so different from here; it’s much more difficult… Here we work, travel, you can go to a store and buy what you want…. It’s one thing for you to visit Brazil, but it’s a completely different thing to live there, understand?

–Lila, 23 years old, lives on Martha’s Vineyard

I would work so much, hard work. I would work 16 hours per day. My boss really liked the way I worked because I did it well. So each day I learned more and developed my English skills. I really like it there, but I can’t work because I have a serious back injury that I think is a result from the work I did over there—that is the problem… Because the U.S. is good when you work, you have to work.

–Lúcia, 47 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

I was disappointed with the way I was treated on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, the cold serious way…. Here you are living around Brazilians, you see the heat, the “Hey how are? You good?” where Americans are like: “Hi.” I will confess, on Martha’s Vineyard I felt as an intruder who arrived to your land and was in the way of your lives…. I got there and had to be a slave, a country guy, just another person in the middle of many.

–Neto, 39 years old, lives in Mantenópolis

The majority of mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses who migrate to Martha’s Vineyard do so for the prospect of improving their economic situation, but the emotional dimension is also an important aspect. Guilherme’s emotional comparison of Martha’s Vineyard and Mantenópolis, quoted above, is “bifocal.” In my study I use bifocality as a way to explore how Brazilians navigate their experiences on Martha’s Vineyard relative to their birth towns of Cuparaque and Mantenópolis. Through their ability to relate to one location while living in the other, they develop a perspective that includes a focus on both their origins and their future, on “rooting and routing.”

The majority of mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses who migrate to Martha’s Vineyard do so for the prospect of improving their economic situation, but the emotional dimension is also an important aspect. Guilherme’s emotional comparison of Martha’s Vineyard and Mantenópolis, quoted above, is “bifocal.” In my study I use bifocality as a way to explore how Brazilians navigate their experiences on Martha’s Vineyard relative to their birth towns of Cuparaque and Mantenópolis. Through their ability to relate to one location while living in the other, they develop a perspective that includes a focus on both their origins and their future, on “rooting and routing.”

Within the transnational process of maintaining a connection between their hometowns and Martha’s Vineyard, through remittances, travel, and social media, many mantenopolitanos and cuparaquenses develop a reality that is based on both locations simultaneously. They continue their customs of origin to overcome feelings of isolation on Martha’s Vineyard, while familiarizing themselves with the life dynamics of the island and finding a place where they fit in. Bifocality is a dual frame of reference in which migrants find a sense of belonging in both Brazil and Martha’s Vineyard, reshaping their reality and goals and causing them to consider a life that is beyond one location or the other.

Sasha Iammarino graduated in May with a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies (World Studies Program) and a Plan in anthropology and photography, specifically on the sending and receiving travel patterns of Brazilians on Martha’s Vineyard. She plans to continue her research in Brazil and the U.S.

Spirits and Memory

“The narratives of people who lived through the Khmer Rouge era and resettled in the United States are characterized by disruption and displacement,” says Emily Tatro, who also completed a Plan on the emigrant experience. She explored the medical and spiritual beliefs of Cambodians and Cambodian Americans, a population profoundly affected by political tumult, violence, and war. “Spirits deeply impact emigrants, altering the linearity of time and infiltrating the porousness of memory,” says Emily. “Spirits speak to the often-silenced ruptures, absences, and losses that characterize emigrants’ experiences.” Emily conducted her research fully aware that the stories she collected rested on social, political, and cosmological ground that continues to shift, and aware of her own biases as an outsider. “I include my own stories to remind me of my inescapable subjectivity.” Photo by John Willis

“The narratives of people who lived through the Khmer Rouge era and resettled in the United States are characterized by disruption and displacement,” says Emily Tatro, who also completed a Plan on the emigrant experience. She explored the medical and spiritual beliefs of Cambodians and Cambodian Americans, a population profoundly affected by political tumult, violence, and war. “Spirits deeply impact emigrants, altering the linearity of time and infiltrating the porousness of memory,” says Emily. “Spirits speak to the often-silenced ruptures, absences, and losses that characterize emigrants’ experiences.” Emily conducted her research fully aware that the stories she collected rested on social, political, and cosmological ground that continues to shift, and aware of her own biases as an outsider. “I include my own stories to remind me of my inescapable subjectivity.” Photo by John Willis