Green Mountain Feminism

By Kelly Hickey

The feminist movement in the 1970s suffered from serious divisions, based on race and class, in cities across the nation. Through the oral histories of feminist activists from the region, senior Kelly Hickey explores how Vermont provided a unique environment and a haven for the movement.

During the second-wave feminism of the 1970s, American women across the socioeconomic spectrum fought against the insufficiency of their domestic identity of “wife and mother.” It would be easy to assume a coalition between middle-class activists and working-class women during that time, but the reality is far more complex. With notable exceptions, the vast disconnect between women solely fighting sexism and those with added layers of oppression, especially class and race, proved too difficult to overcome for most second-wave feminists. Why did attempts to be more inclusive fail? How does our collective memory of second-wave feminism reflect the reality of its exclusivity?

These questions become more manageable when examined locally. Southern Vermont served as a hotbed for radical political and social activities in the ’70s, with activists from cities nationwide moving “back to the land” in attempts to heal their broken society. I spoke with a range of women from Brattleboro, Putney, Guilford, and Marlboro, to find out more. They were involved in communes, art communities, women’s health services, and legal counsel. All of them spoke eagerly and candidly about their activities in the ’70s, with the hindsight to truly analyze them, and they were each interested in and excited for class-based activism in the present day. All the women I spoke with were delightful, and I owe a great deal to their willingness to share.

Their stories corroborate other accounts from more-public figures, but certain particularities make them unique. Firstly, and perhaps foremost, Vermont was largely rural in the ’70s, and remains so to a vast degree today. Much of the city-based organizing of groups like Cell-16 and the Redstockings, radical feminist groups with socialist ideologies that included class struggle, was impossible here. Cities hold lots of energy, but rurality has its benefits too. The archetype of the Vermont farm woman carries with it strength and resilience. Women here were already working alongside men when feminists in cities pushed for workplace equity. They already did hard physical labor, and mechanical or technical work that no city woman would be expected to do. When activists from the city arrived in Vermont, they felt at home.

“We were all doing things like fixing cars and carrying wood, stuff like that,” said Vermont State Representative Mollie Burke, who moved to Vermont in 1970 and has been active in the Brattleboro community as an artist and teacher. “Things traditionally associated with guys. So I think we thought, this is a liberation, of sorts. To feel like you’re not gender-bound by anything that you do.” That hard-work ethic was a treasured part of Vermont feminism that continues to this day.

Along with rural living, feminists in Vermont had particular opportunity in terms of inclusion. Most farm workers and small-town dwellers at the time were working class, and the activists and organizers who migrated here were mostly college-educated children of the middle class. There was vast opportunity for cross-class dialogue, which occurred only in a limited sense, but which surely affected the flavor of local feminist organization as compared to feminist groups in other regions.

Of course, Vermont populations were, and still are, almost entirely white, so feminism in the region had little to deal with in terms of racial tension. The lack of racial diversity couldn’t be considered an asset to any burgeoning social movement, but it is a fact that influenced the way women’s liberation organizations were run. Instead of hearing directly from women of color, in many cases Vermont feminists had to sympathize from afar with situations quite removed from their daily lives. Isolation could be difficult in other ways, as women in rural Vermont had fewer interactions with other politically active women than did women living in, say, New York.

Feminist women in rural Vermont certainly lived a different existence than many city-based feminists in the ’70s. Those who could afford to attend conferences and trainings elsewhere, those who could spend time and money on higher education, and those in professional networks kept the rest of the women connected to feminist movements across the nation. In Vermont, as in other rural areas, the middle class served as the links in a network of poor or otherwise marginalized women.

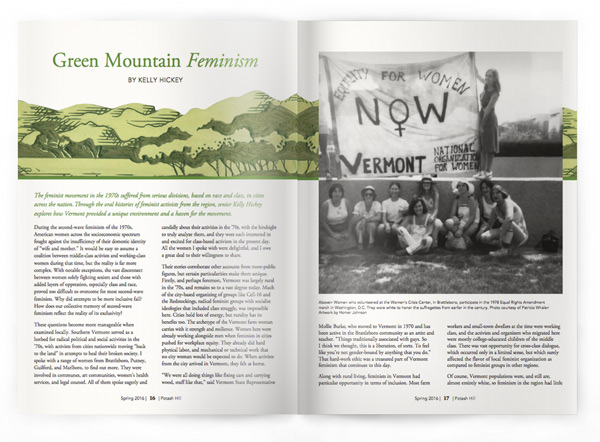

Certain issues in particular did ignite cross-class coalition among women. One of the most serious and significant of these was violence against women. The Women’s Crisis Center in Brattleboro, and presumably other women’s health clinics around the country, provided safe space for women to talk about their abuse, their fears, and their needs. Women realized that domestic violence was an issue for all of them, regardless of background.

The Honorable Patricia Whalen is a local judge who founded the Rural Women Leadership Institute of Vermont and served on the International Criminal Tribunal for Bosnia. In the ’70s, Patti worked at the Women’s Crisis Center, which she helped found, providing legal aid to low-income women. She described one incident where a wealthy woman with beautiful clothes came to the center, and the other women resented her right away. She was very attractive and had no outward signs of being beaten like the others.

“She said, ‘Yeah, you’re right. My husband would never do that to me, because he would never want the public to see that he hit me,’” recounted Patti. “And then she just pushed her sleeve up, and she said, ‘No, he just put his cigarettes out on me all the time.’ She was just horribly burned and scarred. And the women were like, ‘Holy crap, my husband never did that to me. Wait a minute, that’s, like, really bad.’ And so there was always common ground found in stuff.”

As these crisis centers started to use consciousness-raising circles as healing spaces for women, more cross-class interactions and sympathies became possible. Violence against women is more prevalent in lower economic brackets, and working-class women also tend to need more legal assistance and time in shelters after leaving abusive partners. But while most of the long-term clients of the crisis center were working-class women, middle-class and wealthy women who visited the clinic for shorter-term support were able to participate in an open and honest cross-class dialogue.

Abortion rights groups and advocates of accessible birth control options also managed to initiate dialogue across class lines, as unwanted pregnancy and family planning are issues with which all sorts of women can identify.

In the end, however, working-class women still didn’t have even close to the options of their middle-class sisters. Mollie Burke experienced the radical ’70s as more of a personal evolution than a group consciousness-raising. Her story of working in a male-dominated, blue-collar environment epitomizes the difference between working-class women and the educated middle class, even in Vermont.

“I worked as a waitress, briefly. I was a terrible waitress,” said Mollie, laughing. “There were other women who worked at this restaurant, that no longer exists, and one woman had six children. And the kid, who was the son of the owner, would boss these women around, and call them ‘girls.’ I mean, it was horrible. But I could get out, you know. They needed to stay.” And truly, education was the pith of it. Many of these activists had no more money than the women they worked alongside and for, but they had the family and educational safety nets to change course when necessary.

In her work at the Women’s Crisis Center and in the region, Patti Whalen has had an intimate perspective on the divergence between poor women and middle-class feminists. She described a shift in consciousness of the middle-class volunteers at the center, from collaborating with low-income feminists to fighting for their own issues.

“I think everybody understood, in a way, that we were going to get a seat at the table,” said Patti. “And then when we got a seat at the table, we were all of a sudden going to chair the table.”

The activists who flocked to Vermont to eschew society in the early ’70s realized their potential power—as members of that very same structure. Patti went on to name women she worked with, women who moved on to run nonprofit organizations, who serve in the legislature, who work for other leading activists and politicians. The welfare fight wasn’t being won, and middle-class feminists developed other priorities. They turned to the Equal Rights Amendment with full force, and the failure to ratify that bill stymied any further momentum across classes.

International women’s rights movements began to pick up at the end of the decade, with more frequent UN conferences and greater popular awareness of rights violations around the world. Issues like child brides and female genital mutilation were easy to oppose for American women across class lines. Yet even in Vermont, which had its unique chapter in the history of feminism, it seems this international outreach has done little to unite women across classes on national feminist issues.

Kelly Hickey is a senior at Marlboro working on a Plan of Concentration in oral history and visual arts. This article is excerpted from a paper that is a work in progress toward Kelly’s Plan, originally written for the Politics of Change class.

Radicals in These Hills

Kelly and other Marlboro students presented their oral history projects in a public event at the Campus Center in December, titled “Radicals in These Hills,” the culmination of their course Politics of Change: Radical Movements of the Late 20th Century. Taught by theater professor Brenda Foley and American studies professor Kate Ratcliff, the class was part of a pilot for a far-reaching collaborative project produced by Vermont Performance Lab (VPL), in partnership with Green Mountain Crossroads (GMC) and the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project. This partnership is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Samara Fund of the Vermont Community Foundation. VPL theater artist Ain Gordon and HB Lozito of GMC co-directed the class, and many of the oral histories were made possible by VPL’s connections to the local community. “The class is part of a larger vision for a Center for Performing Arts and Social Practice that links coursework and community engagement with VPL artists’ research,” says Sara Coffey ’90, VPL founder and director. “One of the many things we hope to create is an archive on local radical movements, a resource for the broader community that will include students’ work, oral histories, and archival materials.” See a video of the whole event.

Small Town Pride

“The Andrews Inn appears to be Vermont’s answer to the Stonewall Inn, a haven for LGBTQ people to be out and proud, to socialize, be free, have sex,” says senior Rainbow Stakiwicz (pictured with interviewee Eva Mondon), a student in last fall’s Politics of Change class. She did her oral history project on the Bellows Falls gay bar, which thrived through “the long 1970s” until closing in 1982 under mysterious circumstances. “It lives in legend and lore, but its life is largely undocumented, considering that it was well known all along the East Coast.” With the help of Robert McBride of the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project and Vermont Performance Lab, Rainbow was able to speak to some of the patrons who are still around. They remember the inn with fondness as a place where they could express themselves at a time when, in most places, they could not. Her project culminated in a short piece of theater based on her findings. See a video of a reading.

“The Andrews Inn appears to be Vermont’s answer to the Stonewall Inn, a haven for LGBTQ people to be out and proud, to socialize, be free, have sex,” says senior Rainbow Stakiwicz (pictured with interviewee Eva Mondon), a student in last fall’s Politics of Change class. She did her oral history project on the Bellows Falls gay bar, which thrived through “the long 1970s” until closing in 1982 under mysterious circumstances. “It lives in legend and lore, but its life is largely undocumented, considering that it was well known all along the East Coast.” With the help of Robert McBride of the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project and Vermont Performance Lab, Rainbow was able to speak to some of the patrons who are still around. They remember the inn with fondness as a place where they could express themselves at a time when, in most places, they could not. Her project culminated in a short piece of theater based on her findings. See a video of a reading.