Gender in the Way We Move

By Kristin Horrigan

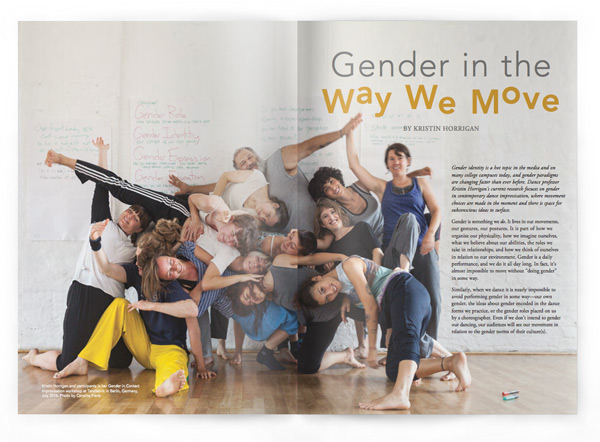

Gender identity is a hot topic in the media and on many college campuses today, and gender paradigms are changing faster than ever before. Dance professor Kristin Horrigan’s current research focuses on gender in contemporary dance improvisation, where movement choices are made in the moment and there is space for subconscious ideas to surface.

Gender is something we do. It lives in our movements, our gestures, our postures. It is part of how we organize our physicality, how we imagine ourselves, what we believe about our abilities, the roles we take in relationships, and how we think of ourselves in relation to our environment. Gender is a daily performance, and we do it all day long. In fact, it’s almost impossible to move without “doing gender” in some way.

Similarly, when we dance it is nearly impossible to avoid performing gender in some way—our own gender, the ideas about gender encoded in the dance forms we practice, or the gender roles placed on us by a choreographer. Even if we don’t intend to gender our dancing, our audiences will see our movement in relation to the gender norms of their culture(s).

Gender is a social construction. The term gender refers to a particular culture’s ideas about what behaviors and attitudes are expected of people based on their biological sex and its intersection with other factors, including age, role in society, race, class, and sexual preference. In most Western cultures over the past several hundred years, gender has been constructed as a binary, with masculine and feminine understood as the only two options. More and more in Western cultures, this binary is cracking open, revealing many more than two possibilities, including transgender, gender neutral, gender fluid, and genderqueer identities, plus a range of different masculinities and femininities.

Our ideas about gender are projected onto us when we are very young. We begin learning about gender roles in early childhood, absorbing messages from a wide variety of sources: family members, school, toys and games, clothing, the media, and so on. Even though most of us eventually form our own conscious gender identities as adults, we still carry with us the gender education we accumulated during our early years. This cultural knowledge is deeply embedded within us, stored in our bodies as much as in our thoughts. We sometimes perform gender roles that are habitual to us, even if we no longer support or identify with them. Our gender expression doesn’t always match our gender identity—especially when we are dancing.

In dancing, particularly in improvisational dancing, our embodied knowledge—both the conscious and the subconscious—comes forth. We make choices about how to take up space, how to organize our bodies, how soft or hard to make our movements, how vulnerable to let ourselves be, how to interact with others, how to present ourselves to an audience. Because of our gender education, we have more practice with certain gestures, postures, movement qualities, and ways of relating to space than with others. These habits and patterns emerge among our more conscious choices. For example, as a feminine-educated person, I have been taught to have a soft, flowing, yielding movement quality, and this comes up quite frequently in my dancing, whenever I’m not making a conscious choice. Strong, direct actions are less familiar to me and take more conscious thought.

Most notions of gender are inherently limiting, and certainly the binary gender education that most of us were exposed to as children was based entirely on limits. Girls are quieter and better behaved, boys are more physical and energetic, girls should smile and look pretty, boys don’t cry, and so forth. But our dancing need not be restricted in this way. What movement possibilities are we excluding when we allow gender to shape our movement? How could awareness of the way gender is affecting our movement offer us greater range and freedom of expression in our dancing?

These questions have been at the heart of my research for the past several years. They’ve been particularly interesting to explore in the dance form called contact improvisation (CI), an athletic dance of improvised partnering. In this dance, the dancers explore the movement that is possible when two bodies are in physical contact, using each other’s support to balance and communicating through weight and momentum. As the dancers lift each other, fall and roll together, they are constantly responding to their partner. Their attitudes toward strength and vulnerability, risk taking and protection, leading and following are all revealed through their movements.

Emerging from the avant-garde dance performance scene in the early 1970s in the U.S., contact improvisation embodies some of the popular politics of its day. Influenced by the feminist movement, contact improvisation contains no set gender roles. People of any gender can dance together, and all movement possibilities are open to every dancer. There are no leader or follower roles. No roles at all, in fact, except those one might take on spontaneously in the course of a particular dance.

In fact, to dance contact improvisation well, one must embody a range of qualities and skills from across the gender spectrum. All CI dancers need to support and be supported, to initiate and follow, to be soft and to be strong, to sense and to act. In combining both masculine- and feminine-coded qualities, CI technique actively queers gender, inviting us all to play beyond the confines of the binary.

For this reason, contact improvisation has the potential to be a paradise of gender freedom. Indeed, some of my transgender students at Marlboro have said that contact improvisation class allowed them the most freedom they’ve ever experienced from societal pressures around gender.

And students of all genders have noted the room CI gives them to try out ways of moving that they’ve previously denied themselves, including movements that are gender coded. And at the same time, contact improvisation is a dance form to which we bring our full selves—our creativity, our physicality, our histories, and yes, our genders and our sexuality. Very often, patriarchal and heteronormative patterns creep in. For example, it may be more familiar and comfortable for a masculine-educated person to lead their partner, to lift rather than be lifted, and to favor movements that depend on strength rather than those that require vulnerability. However, this is very limiting to their dancing and to the person dancing with them.

In order to achieve the potential freedom of the dance, dancers need to raise their awareness of how their gender education and their gender identity are influencing their choices on the dance floor. Whether or not a person chooses to inhabit a traditional gender role off the dance floor, within the dance form of contact improvisation observing a fixed gender role restricts one’s ability to participate fully in the dance.

A first step is to understand better how gender lives in movement. I suggest you try an experiment. Pick a simple daily action—for example, sitting down in a chair, opening a bottle, or taking off a sweater—and perform it your usual way. (Yes, really do it!) Then try it again a few times with “more masculinity,” “more femininity,” more gender neutrality, more queerness, and so on. Yes, you are drawing on stereotypes to do this. While often exaggerated, stereotypes provide valuable information about (your embodied) cultural ideas around gender. You may notice that you have a number of different ideas about what it means to be masculine, feminine, gender neutral, or genderqueer. Try them all.

What do you notice changing when you attempt to add more masculinity, femininity, gender neutrality, or queerness to your movement? What changes in terms of how much space you use, how much of the body is involved, how conscious you are of how you look, how much force you use, how efficient the movement is, how much of the body contributes to the action, how direct or indirect the pathways are? Can you imagine how these gender-coded ways of movement could translate beyond daily gestures into the broader actions of dancing?

If this experiment makes you curious, I encourage you to look up Iris Marion Young’s classic gender theory article “Throwing Like a Girl,” in which she theorizes about gendered mobility and spatiality. Young draws connections between attitudes toward children (for example, that little girls should take more care not to get hurt or dirty) and movement patterns that last into adult life (for example, that feminine-educated people are more likely to hesitate before taking a physical risk, thus causing a disconnection between intention and action). While times have changed much in the nearly 40 years since Young wrote this article, many of her ideas are still found in our bodies today.

Deepening the investigation, dancers can ask themselves questions about how they interact with their dance partners. What roles do they take in CI dances? Instigator? Listener? Caretaker? Clown? Do they offer different dances to people of different genders? Do they expect different things from their dance partners based on what they perceive as their gender?

If dancers ignore questions about gender and continue to perform it unconsciously in their contact improvisation, they limit the kinds of dances they can have, the diversity of the community that practices CI, and the possibility to step out from under the gendered expectations of their societies.

When we take the time to notice and question our own gendered patterns of movement and interaction, we help liberate ourselves from the limits of our gender education—both in our dancing and in our daily lives. This allows us a greater range of possibilities in our movement and more space to truly listen to the dance that is happening. When we learn to stop making assumptions about each other’s gender (and sex and sexuality) and stop treating each other in gendered ways on the dance floor, we can begin to make our communities more inclusive of queer and gender-nonconforming people. Lastly, by questioning the gendered behaviors that emerge in our dancing and in our daily actions, we invite critical reflection on power structures both in and outside the space we are occupying.

Kristin Horrigan is a professor of dance and gender studies, and an internationally known teacher of contact improvisation. Her research on CI and gender was recently published in the Winter/Spring 2017 issue of Contact Quarterly, in an article titled “Queering Contact Improvisation.”

Body Memories

“Contact improvisation was influential in how I began to view my body and movement habits with other dancers,” says senior Lucy Hammond, who is working on her Plan in anthropology and dance/gender studies. “CI is the most intentionally gender-neutral and physically accessible space that I have experienced as a dancer. There are far fewer borders and ‘shoulds’ and ‘should nots.’” Lucy’s research explores gender conditioning and performance through movement and thought patterns. She is investigating her own gender performance and facilitating workshops allowing others the space to research memories of gendered experiences as well. “We will look at how habits might mask discomfort, or take away or give bodily space and voice,” says Lucy. “Understanding gender performance and its origins, growth, and deconstruction brings into question coloniality, hetero-patriarchy, and their memory in bodies.”

“Contact improvisation was influential in how I began to view my body and movement habits with other dancers,” says senior Lucy Hammond, who is working on her Plan in anthropology and dance/gender studies. “CI is the most intentionally gender-neutral and physically accessible space that I have experienced as a dancer. There are far fewer borders and ‘shoulds’ and ‘should nots.’” Lucy’s research explores gender conditioning and performance through movement and thought patterns. She is investigating her own gender performance and facilitating workshops allowing others the space to research memories of gendered experiences as well. “We will look at how habits might mask discomfort, or take away or give bodily space and voice,” says Lucy. “Understanding gender performance and its origins, growth, and deconstruction brings into question coloniality, hetero-patriarchy, and their memory in bodies.”