Panoptic Wilderness

By Marcus DeSieno ’10

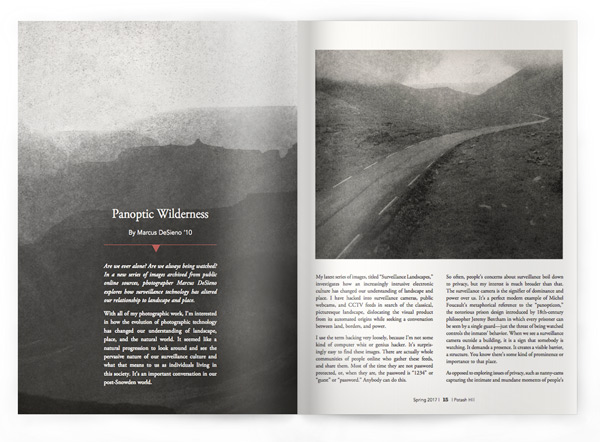

Are we ever alone? Are we always being watched? In a new series of images archived from public online sources, photographer Marcus DeSieno explores how surveillance technology has altered our relationship to landscape and place. With all of my photographic work, I’m interested in how the evolution of photographic technology has changed our understanding of landscape, place, and the natural world. It seemed like a natural progression to look around and see the pervasive nature of our surveillance culture and what that means to us as individuals living in this society. It’s an important conversation in our post-Snowden world.

My latest series of images, titled “Surveillance Landscapes,” investigates how an increasingly intrusive electronic culture has changed our understanding of landscape and place. I have hacked into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in search of the classical, picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while seeking a conversation between land, borders, and power.

My latest series of images, titled “Surveillance Landscapes,” investigates how an increasingly intrusive electronic culture has changed our understanding of landscape and place. I have hacked into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in search of the classical, picturesque landscape, dislocating the visual product from its automated origins while seeking a conversation between land, borders, and power.

I use the term hacking very loosely, because I’m not some kind of computer whiz or genius hacker. It’s surprisingly easy to find these images. There are actually whole communities of people online who gather these feeds, and share them. Most of the time they are not password protected, or, when they are, the password is “1234” or “guest” or “password.” Anybody can do this.

So often, people’s concerns about surveillance boil down to privacy, but my interest is much broader than that. The surveillance camera is the signifier of dominance and power over us. It’s a perfect modern example of Michel Foucault’s metaphorical reference to the “panopticon,” the notorious prison design introduced by 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham in which every prisoner can be seen by a single guard—just the threat of being watched controls the inmates’ behavior. When we see a surveillance camera outside a building, it is a sign that somebody is watching. It demands a presence. It creates a visible barrier, a structure. You know there’s some kind of prominence or importance to that place.

As opposed to exploring issues of privacy, such as nanny-cams capturing the intimate and mundane moments of people’s lives, it seemed more interesting to me to look out at landscapes that were devoid of humans. The melancholic images that I’m assembling speak to how this technology shapes our understanding of place, and evoke conversations around power and ownership. That really intrigues me: why, on this road in the middle of nowhere, Kansas, is there a surveillance camera? Some of the locations, such as those in national parks, have a certain prominence or significance. But most of the places I stumble upon have no rhyme or reason. Maybe it’s a traffic camera; maybe it’s a weather camera. This technology is used for a variety of purposes besides the nefarious, but it certainly shapes our psyche when we see these things.

As opposed to exploring issues of privacy, such as nanny-cams capturing the intimate and mundane moments of people’s lives, it seemed more interesting to me to look out at landscapes that were devoid of humans. The melancholic images that I’m assembling speak to how this technology shapes our understanding of place, and evoke conversations around power and ownership. That really intrigues me: why, on this road in the middle of nowhere, Kansas, is there a surveillance camera? Some of the locations, such as those in national parks, have a certain prominence or significance. But most of the places I stumble upon have no rhyme or reason. Maybe it’s a traffic camera; maybe it’s a weather camera. This technology is used for a variety of purposes besides the nefarious, but it certainly shapes our psyche when we see these things.

A lot of this work is about being an archivist, having a selection process, trying to find those moments that present a heightened emotional state, or aesthetic moments that interest me. Essentially, I’m a curator of the surveillance internet. I find this really intriguing because I’m not only thinking about the nature of the technology, but of another layer—the ways in which I’m using the internet to construct this work. I deflate this idea of the artist as genius by using what’s available to me, what’s available to anybody.

I don’t alter the images, other than converting the ones in color to black and white. I like the starkness of the monochromatic image, which perhaps heightens the sense of drama. Black and white dislocates the landscape, so the identifiers of place are more limited. Much of the time I specifically seek out imagery that’s in soft focus, that has an impressionistic feel, that might have raindrops on the lens. I’m interested in cameras that might be grimy, and haven’t been serviced for a while—in finding imagery that abstracts the landscape in some way, that can speak to a history of landscape painting as well. It’s just another layer to this work, another vector in the history of how we perceive the landscape.

I don’t alter the images, other than converting the ones in color to black and white. I like the starkness of the monochromatic image, which perhaps heightens the sense of drama. Black and white dislocates the landscape, so the identifiers of place are more limited. Much of the time I specifically seek out imagery that’s in soft focus, that has an impressionistic feel, that might have raindrops on the lens. I’m interested in cameras that might be grimy, and haven’t been serviced for a while—in finding imagery that abstracts the landscape in some way, that can speak to a history of landscape painting as well. It’s just another layer to this work, another vector in the history of how we perceive the landscape.

Through these empty landscapes I want to create a contemplative state of mind. When my viewer looks at the images—when they’re taken into these landscapes— they can reflect on their own relationship to surveillance technology and how it’s affected them, whether they know it or not. The very act of someone surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place. Ultimately, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through the obfuscated, melancholic images found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Marcus DeSieno received his MFA in studio art from the University of South Florida, and is currently a visiting photography professor at Marlboro. Marcus’s work has been exhibited nationally and featured in a variety of publications, from Smithsonian to Wired. In August, his “Surveillance Landscapes” series was selected for Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50, a juried competition for emerging photographers, for pushing the boundaries of the medium. This has led to a book deal with Daylight, a nonprofit publisher of fine art and photography books.

Corrupted Video Files

“The videos of David Hall were meant to take the viewer out of the conventional televisual experience,” says senior Ian Grant, referring to the artist who introduced “TV Interruptions” on Scottish television in the 1970s. “Much like Hall, my own work will often critique the culture of mainstream media, and creates an aesthetic with this in mind.” Ian is completing his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, with a written portion on British video art in the 70s and 80s and an exhibit of photographs, video art, and video installation. “My work often involves a new art form called ‘glitch art,’ which causes the viewer to question their experience.” An example of this (left) shows a still from corrupted video files Ian took during the anti-Trump protest in New York City the night after the election.

“The videos of David Hall were meant to take the viewer out of the conventional televisual experience,” says senior Ian Grant, referring to the artist who introduced “TV Interruptions” on Scottish television in the 1970s. “Much like Hall, my own work will often critique the culture of mainstream media, and creates an aesthetic with this in mind.” Ian is completing his Plan of Concentration in visual arts, with a written portion on British video art in the 70s and 80s and an exhibit of photographs, video art, and video installation. “My work often involves a new art form called ‘glitch art,’ which causes the viewer to question their experience.” An example of this (left) shows a still from corrupted video files Ian took during the anti-Trump protest in New York City the night after the election.