Storied Faculty Members Move On

Three of Marlboro’s most senior faculty will be retiring this academic year, after a combined 134 years of dedicated service to the college and mentorship to countless adoring students. The college made the decision to remove a retirement benefit introduced in 2007, for budgetary reasons, and T. Wilson (literature and writing), Geraldine Pitmann de Batlle (literature), and Stan Charkey (music) elected to take the benefit before it disappeared.

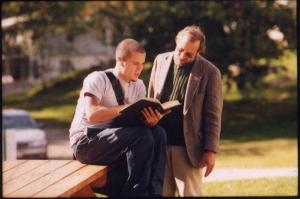

“How does one describe the singular, formative love between teacher and student?” asks Amanda DeBisschop ’10, who was one of T.’s Plan students and is now a teacher herself at Leland & Gray High School in Townshend, Vermont. We’re not sure we have the answer, but we figure that former students of these formidable faculty members will be in the best position to take a stab at it.

Amanda continues, “From the first, I knew that I wanted to know T. Hunter Wilson. I felt soon after seeing him on campus, at Town Meeting, that there was something I had to learn from him. And what I learned was the incredible feeling of someone taking my writing seriously. In my entire life, there had been no one to assess my work on an academic level. He helped me to feel credible. He treated my work as though it were a contribution to the larger world of poetry. He also taught me the value of accountability in a partnership, both as a student and doubly as a teacher, now, of my own students.”

T. first taught writing and literature at Marlboro in 1968, after receiving his MFA from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and in addition to teaching he has done stints as dean of faculty and, twice, as director of the World Studies Program. Always engaged in the campus community, he has served as Town Meeting moderator, Community Court justice, and member of countless committees.

“I still, 40-plus years later, vividly remember the eagerness with which I looked forward to our meetings,” says Kathryn Kramer ’75, now a published author and professor of literature at Middlebury College. “I could have listened from dawn till dusk to T. talking about my manuscript. This kind of attention, this kind of uninflected reading, is an enormous gift to a young writer, and I have remembered that experience over the years as I’ve gone on to teach writing myself.”

“I think the best thing about working with T. was that he really did let you come to conclusions on your own,” says Cate Marvin ’93, now a published poet and professor of creative writing and literature at Colby College. “In this respect, he was very patient. He also acknowledged the hard work of writing. One week I turned in 11 poems, but they were all bad. And T. told me that the fact I’d written that many poems and didn’t give up was a better sign than if the poems had been good. So he taught me the notion of perseverance.”

“T. is a brilliant teacher and editor, and he made me feel brilliant, too,” said Molly Booth ’14, whose Plan project was the young adult novel Saving Hamlet, published by Disney Hyperion last November. “I left his office charged with energy, and annoyed with the 20 steps it took to get to the library, where I could sit down and write. With T., I learned how to write and edit, how to develop characters, how to listen to my creative gut . . . everything we did together applies to what I do now. When I feel uncertain in my writing, I return my mind to Marlboro, and think what discussion T. and I would be having about this word, or that character.”

Nearly as senior as T. is Geraldine Pittman de Batlle, who joined Marlboro in 1969 after advanced graduate study at Southern Illinois University and Columbia University. Known for her passion for literature ranging from English Romantic poetry to modern fiction, Geri won the adoration of students who enjoyed working closely with her on projects of mutual interest.

“Geri conveyed a love of literature that was infectious,” says Chris Davey ’93, a freelance editor who says he daily applies the skills she taught. “Her request that students show attentiveness to and respect for words struck me as profoundly ethical, as a call to bear witness to the power of words and the effects of that power, to recognize the ways great literature enacts empathy, and then to go beyond, to seek to hear for oneself ‘the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat,’ to brave ‘the roar which lies on the other side of silence.’”

“The amount of writing I had to do for Geri was intense,” says Ron Mwangaguhunga ’94, now a working writer and editor in New York City with a novel on the way. “Good or bad thoughts, Geri wanted me to get them on paper just to get in the practice of regular writing. Her patience, compassion, and, above all, demand for excellence—and always, always, more writing— helped me massively with the work I do today.”

“I was always happy working with Geri,” says Sue Crimmins ’89, now a landscape designer. “I saw her every day, and we made each other smile. Even on those days that I had not finished even a paragraph of my Plan, she held me as closely as any member of her family. We would sit right down next to each other and plow through all the words and all the sentences and all the paragraphs, clarifying every idea. She was my teacher, but also a good friend, and my strictest tutor. I am still sorting my ideas, and words, and reaching for clarity in everything I do.”

“Geri has tremendous respect and patience for literature,” says Ryan Stratton ’11, who works as an admissions counselor at Marlboro. “I think that one of the best lessons I learned from Geri was reverence—in a contemporary world where irony is used as social and intellectual capital, I think it was a humbling experience to really sit down and listen to what Dante was trying to say about self-growth and love for others. Geri had a reputation for being a tough teacher—I would say that she has only the highest expectations for her students, because she knows them and has faith in them, and wants them to reach their fullest potential.”

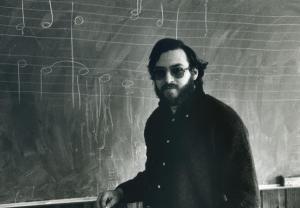

Music professor Stan Charkey, the Luis C. Batlle Chair in Music, has taught music at Marlboro since 1977, when he received his Master of Music degree from the University of Massachusetts. A composer and performer of note, Stan had premieres of new works performed in Paris, Los Angeles, Washington, and of course Marlboro.

“I appreciated that Stan held his students to high standards, but always allowed us the space to pursue our interests independently,” says Allen Magana ’13, a graduate student in Latin American and Iberian studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “He respected us as scholars and never expected anything less from our work. Stan offered me the opportunity to prove to myself that I have the ability to complete top-level scholarship. This experience gave me the confidence to continue to pursue academic research, and I hope someday to foster this same love of scholarship in my own students.”

“My favorite part about working with Stan is that he was extremely open-minded to my ideas as a composer,” says Felix Jarrar ’16, already an accomplished composer and pianist in the New York area. “During my lessons with him, he would always give me constructive feedback on how my musical gestures would or wouldn’t work toward my larger musical goals. He had a lot of really great suggestions for pieces to listen to if I found myself ‘stuck.’ My work with Stan has helped me immensely since leaving Marlboro. When I write music, I use all of the contrapuntal and compositional skills he taught me.”

“Stan’s regard for a student was, for me, ideal,” says Peter Blanchette ’92, a musician, composer, and founder of the Happy Valley Guitar Orchestra. “He neither pampered you through the maddeningly tricky counterpoint exercises, nor disrespected your earnest effort. On the other hand, he would expose the weaknesses in your results with firmness, followed by excellent suggestions of how to improve. He taught me more about what makes great music tick than anyone else in my life, and every single day that I work, I apply musical understanding that he brought into my life.”

“He was always ready to put some beautifully intricate piece in front of us and have at it,” says Mike Harrist ’10, a professional musician and music teacher in Boston. “His joy in reading and playing is deep and infectious. Looking back, I’ve learned many lessons just from this one aspect of our time together. Joy in making music and a realistic perspective on one’s ability are not antithetical. Holding both together fuels improvement and leads to a grounded musicality. Stan’s teaching and high standards continue to inspire me to be a better musician and more rigorous thinker.”

One of Amanda DeBisschop’s fondest memories is when she joined T. Wilson to hear poet Gary Snyder, one of his mentors, and they approached Gary after the reading. When Gary said to T., “Shouldn’t you be close to retiring now?” Amanda piped in, “He can’t retire. I wouldn’t know what to do.”

All in the college community share Amanda’s sentiments about T., and feel just the same about Geri and Stan, but acknowledge that this is a shortsighted response. Amanda concurs: “I simply want every other Marlboro student to have access to the person who taught me the most valuable things that I know: to be a conscious part of a community, to write as though my life depends on it (and it does), and to do good work.”