Sustaining Wide Open Spaces

By Charles Curtin ’86

A career conservation scientist and co-editor of the recent book Complex Ecology, alumnus Charles Curtin reflects on 30 years of change in ecology and conservation.

She needs wide open spaces Room to make her big mistakes She needs new faces She knows the high stakes. —Dixie Chicks

Early in my career, the Dixie Chicks song Wide Open Spaces was commonplace on the airwaves and one I frequently heard as I drove to my field sites in southern Arizona and New Mexico. Then as now, the song’s refrain aptly summarizes some of the core elements needed to effectively confront challenges such as climate change, mass extinction, and a myriad of other issues facing the planet: the need to work at large scales where the intrinsic dynamics of the system are expressed; the need for patience and humility where social and ecological processes interact in complex and unpredictable ways, where you frequently learn as much or more from failures as successes; the need to engage with a variety of collaborators to get things done in often socially and politically contentious settings. And indeed the stakes are high: what hangs in the balance is much more than local environmental concerns or professional standing, but the very fabric and integrity of our fragile planet.

Scientific careers, like life itself, are usually a work in progress. Like a series of experiments, one’s thinking evolves to reflect emerging realities. When enough scientists and other thinkers individually and collectively grapple with similar issues, there can arise a new consensus that marks a transition in society’s perspective. We appear to be on the cusp of such a transformation right now as the sorts of linear, “clockwork” views proposed by Isaac Newton, Adam Smith, and others hundreds of years ago in the Enlightenment era are breaking down in the face of an intrinsically messy reality.

Climate change and the extinction crisis show that the problems humanity now faces are not linear and predictable but complex and dynamic, with outcomes far greater than the sum of their parts. Surprise is becoming thenew norm. Events such as Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake and tsunami at Fukushima highlight the need for a different kind of science and policy, one that addresses challenges with a new humility and pragmatism. My own journey of discovery parallels this important transition in scientific thinking.

The first phase of my evolving thinking on science and complexity began with my time at Marlboro College, where my professors (especially Bob Engel) introduced me to the view that quality science was both rigorous and elegant. Classic ecological studies, such as those of luminary ecologist and Marlboro alumnus Robert MacArthur (brother of Marlboro physics professor John), transformed ecology from primarily a descriptive to a quantitative discipline. But equally important, the MacArthur brothers and collaborators showed experimental ecology to be something of immense beauty.

In paraphrasing Pablo Picasso, Robert once stated, “Science is the lie that helps us see the truth,” recognizing that science, like art, is as much about insight as a search for objective reality. Especially in the post-war era from the 1950s through the early 1980s, the relatively simple math available to ecologists before computational power became widespread meant that much of the science of the period was a gross simplification of reality. But this simplification led to an elegance and focus on big conceptual questions that have rarely been attempted since.

Following Marlboro, my graduate career was also marked by a search for conceptual elegance. From research on the recovery of subalpine ecosystems in Colorado to studies on the impact of climate and land-use change on species, my approach embraced a search for simple solutions to complex challenges. This was followed by a post-doc at the University of New Mexico with ecologist James H. Brown, managing studies of desert ecological communities (work I had read and admired as an undergraduate at Marlboro).

Brown’s work was another series of exceedingly elegant experiments that provided clarity through simplifications of reality. However, during my post-doc, I also had the opportunity to spend time at a complex-system think tank, the Santa Fe Institute (SFI). My time at SFI would forever change the way I viewed science and conservation, by recognizing that elegance did not necessarily require a focus on simplification. Instead, a fundamental challenge of science and conservation was to embrace reality by grappling with complexity.

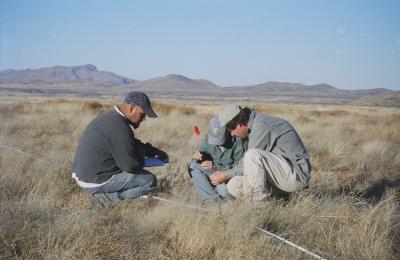

Out of my interest in demonstrating that experimental ecology could incorporate complexity arose the McKinney Flats Project, a nearly 9,000-acre experiment in southern New Mexico. This project was a microcosm of study plots spanning a million-acre conservation planning area, and was intended to provide insight into the dynamics playing out across the entire intermountain West. However, it soon became apparent that to understand systems at the size of even 9,000 acres would take at least 12 to 16 years. This period was far too long to acquire the requisite publications to attain tenure at most universities. So a new sort of science was needed, one embedded in vast landscapes and that involved working closely with remote rural communities.

I left academia and founded a nonprofit research institute that provided the institutional flexibility and ability to produce the answers I thought society most needed. As it turned out, McKinney Flats was as much a social experiment as a biological one. I was simultaneously having cowboys manage a 200-head herd of cattle, undertaking 8,000-acre prescribed burns, introducing species such as prairie dogs, and working with biologists on a diversity of ecological sampling. Doing all this while also sustaining a partnership with the rancher-led conservation organization Malpai Borderlands Group proved to be both challenging and insightful. No longer was I applying comparatively simple, replicated experimental designs, but working amid the intrinsic messiness of the “real world,” where social dynamics are just as important as ecological ones.

Although the McKinney Flats study ended prematurely, due to the 2007–2008 recession and concurrent social upheaval along the US-Mexico border, valuable lessons had been learned. I found that effective science and conservation are a result of social design as much as scientific replication—putting in place the preconditions for success that most biological scientists and conservationists rarely consider. I recognized that there needed to be a greater synthesis of social and ecological approaches.

My experience gave me a new perspective now widely accepted, but still seldom attained, where one does not think along purely disciplinary boundaries but views disciplines as different tools in a diverse tool kit. The role of the researcher is to select the right tool for the job, rather than merely applying a paradigm because it is what you know. Theories were no longer suppositions to be defended, but ideas to be explored and thoughtfully challenged. Complexity is embraced, rather than avoided— the intrinsic messiness of the world is designed into the study, rather than designed out of it.

In tandem with McKinney Flats, and in the years that followed, I embarked on a wide range of social and ecological experiments related to collaborative science and conservation. This work engaged a wide array of stakeholders in large-scale problem solving with a focus on involving local people and their values and insights in science and policy. These efforts included fishery recovery in the western Atlantic, collaborative conservation programs in East Africa and the Middle East, and farmer cooperatives in the Midwest and New England. I also co-founded programs on collaboration, complexity, and adaptive management at MIT and other universities.

These experiences were followed by a return to on-the-ground efforts in collaborative conservation in Montana, where what I learned was sobering. It soon became apparent the ideas gleaned from my earlier efforts in large-scale science and conservation were necessary, but not sufficient to keep pace with the increasing rates of environmental and societal change. To mix metaphors, the best of conventional conservation was still mainly a process of rearranging deck chairs (while Rome burns). Yes, we were restoring watersheds and saving a few wolves or grizzly bears. However, we were not fundamentally addressing the most severe threats such as global environmental change, or wholesale transformations of local or indigenous cultures. This was because we were not meaningfully addressing the limitations undermining most science and policy. A fundamental rethink of conservation was needed.

As the social philosopher Tom Atlee noted, “Things are getting better and better and worse and worse, faster and faster, simultaneously,” and current institutions are typically poorly situated to address this reality. Conservation actions too frequently represent halfway measures—in essence, the settling for less damaging outcomes, rather than fundamentally better solutions. In my career, I have to admit, I have too often been complacent in accepting such “solutions.” There were marine policies that mayhave reduced the decline of fisheries but didn’t address the core issue of unsustainable fishing practices, and collaborative organizations that protected endangered species but didn’t address agricultural practices that degrade watersheds and increase greenhouse gases.

Conventional collaborative approaches were essential in building common ground and an understanding of how to conduct conservation at large scales. It is certainly not appropriate to cast aside such testbeds of innovation and problem solving, for they have made enormous contributions to preserving communities and species. However, we need to learn and apply the lessons from decades of experience that have much to teach us about how to design, develop, and sustain more integrated efforts that consider the whole system and not just fragments. In short, we need to move beyond reactive to proactive approaches and policies.

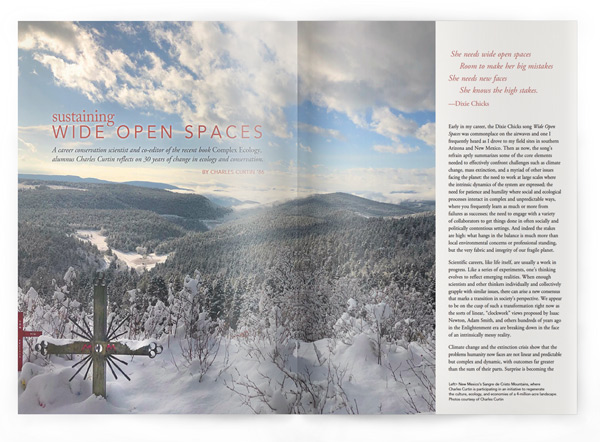

The disappointments of Rio, Paris, and other climate accords, and the relative impermanence of global and national climate policy, strongly suggest that if effective action is to happen, it is not going to come from global agreements but from local engagement and action. It has to be built from the ground up, and right now we’re trying such an approach in the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

The Sangre de Cristo Initiative is seeking to regenerate the culture, ecology, and economies of a 4-million-acre landscape from north-central New Mexico to south-central Colorado. The point of this initiative is to show that conservation is not only sustainable, but can contribute to the integrity of social and ecological systems. Especially in some of the poorest counties in the US, we need to do more than protect nature. We need integrated solutions to the coupled challenges of rising global temperatures and the conservation of species and ecosystems, while engaging disenfranchised rural populations. We’re exploring using biomass energy production technologies to restore forest and watershed health, and fuel economic revitalization of the region while reducing CO2 inputs into the atmosphere.

There are many ways we can rethink conservation and science, but we must recognize that the status quo is often not sufficient, or perhaps even ethical, given the extent of current threats. Projects such as the Sangre de Cristo Initiative illustrate there are alternative frameworks that can make conservation and environmental science more effective in their service to society and the planet. These approaches bring together decades of experience searching for elegance and integrity, incorporating multiple viewpoints, and working across disciplines and ecological boundaries. They require humility to work with what Buddhist teachings call shoshin, or a “beginner’s mind,” where you address complex challenges with eagerness, openness, and a lack of preconceptions. Lastly, these new approaches to conservation include viewing actions as experiments, so one can truly learn from them.

“For a scientist there are worse sins than being wrong; one of them is being trivial.” —Robert H. MacArthur

Charles Curtin is a landscape ecologist and systems design theorist and practitioner who works at the intersection of science and policy, and is founder of BioCultural Connections in New Mexico. He is the author of The Science of Open Spaces: Theory and Practice for Conserving Large, Complex Systems and co-editor of Complex Ecology: Foundational Perspectives on Dynamic Approaches to Ecology and Conservation. His forthcoming book with the working title Prosilience: The Science of Complexity and Integrity is due out next year.

Ecology of the Individual

“Plants are often regarded as no more than resource objects— unfeeling, passive sorts of beings,” says Hailey Mount ’19, who completed her Plan in ecology and environmental philosophy in December. “But new science, technology, and attention to sustainable environmental relationships are allowing us to view the plant world with a new level of detail.” Hailey used a trait-based method of ecology—specifically, looking at the level of individual variation and scaling up and down between other levels from there—to look at how soil acidification could affect tree dynamics in Marlboro’s ecological reserve (Spring 2018 Potash Hill). “I’m exploring how these new techniques in ecology, and the philosophical idea of plants as subjective ‘others’ worthy of empathetic consideration, can come together and improve our environmental relationships, our management practices, and the way we interact with the world.”

“Plants are often regarded as no more than resource objects— unfeeling, passive sorts of beings,” says Hailey Mount ’19, who completed her Plan in ecology and environmental philosophy in December. “But new science, technology, and attention to sustainable environmental relationships are allowing us to view the plant world with a new level of detail.” Hailey used a trait-based method of ecology—specifically, looking at the level of individual variation and scaling up and down between other levels from there—to look at how soil acidification could affect tree dynamics in Marlboro’s ecological reserve (Spring 2018 Potash Hill). “I’m exploring how these new techniques in ecology, and the philosophical idea of plants as subjective ‘others’ worthy of empathetic consideration, can come together and improve our environmental relationships, our management practices, and the way we interact with the world.”