“Marlboro is People”

By Dan Toomey ’79

A legacy alumnus and perennial Marlboro historian reflects on the college’s illustrious past and unique place in the landscape of higher education.

A college’s history is an assemblage of interwoven stories about a place and about the people connected to that place. While every college’s history is different, Marlboro’s is arguably more different from others in numerous ways. I contend that the values and the character of certain individuals, and the life experiences that shaped them, came to constitute the ideals that made the college what it was.

•••

Walter Hendricks, Marlboro’s founding president, and Arthur Whittemore, the first trustee of the college and the first board chair, were close in age, dearly loved the town of Marlboro, and were veterans of the First World War. Arthur Whittemore had led a company through several battles including Meuse-Argonne, the last great battle of the war. He was wounded in action twice. Walter Hendricks had trained over 300 pilots to fly the legendary Curtiss-Jenny, came within a hair’s breadth of being killed numerous times, and watched helplessly as a man who had crash-landed died in the hospital bed next to his.

Arthur Whittemore’s experiences on the Western Front “made him think what way he could be the most use to humanity,” as his eldest daughter once said to me; and Walter Hendricks’ time as a pilot trainer was an experience that impelled him, as well, toward a life of meaning. While Marlboro was in obvious ways a product of the Second World War, it had been the Great War that drove these two men to do good things in the world. Their establishing Marlboro College was one such accomplishment, and it was their planning together over the late spring and summer of 1946 that laid the school’s foundation.

Walter Hendricks’ idea for starting a college on his Vermont hill farm had its beginnings in two educational experiences. The first was his time as an undergraduate at Amherst College, and in particular the time he spent there with Robert Frost; and at the end of World War II, his time as English Department chair at Biarritz American University, when he came to understand that starting a school from scratch was possible. A third influence was his ongoing fascination with utopian experiments and ideals. His vision for Marlboro would blend all of these.

In their book The Perpetual Dream: Reform and Experiment in the American College, Gerald Grant and David Riesman (the eminent sociologist who served many years on Marlboro’s Council of Academic Advisors) have written that there are certain kinds of progressive institutions that “generally begin with a charismatic leader who is often not good at balancing either books or interests and is subsequently expelled.” It is easy enough to draw attention to Walter Hendricks’ character flaws, but as Dick Judd stated to me once, “There wouldn’t have been a college without him.” It was Walter Hendricks’ idea alone to begin a liberal arts college on his Vermont farm, and it was his intellectual courage that helped bring it into being, not his weaknesses.

Walter Hendricks’ mentor Robert Frost had a fondness for Greek and Latin rhetorical devices that he could put to novel use. One of these was “anastrophe,” the inversion of usual word order. In an interview given in the summer of 1956, Frost took the standard phrase “believing in it” and transposed the preposition and pronoun to create “believing it in,” thereby altering the phrase’s meaning to indicate engendering something through the sheer force of belief. So when on an August evening ten years earlier, Walter Hendricks first told his former teacher about his plan for starting a college, Frost grew animated. Here was his old Amherst student about to actualize one his most cherished ideas: bringing idea into matter, or put more poetically as he did in the late poem “Kitty Hawk,” “risking spirit in substantiation.”

Marlboro’s founding president had a particular genius for beginnings, evinced by the remarkable fact that he would found two more colleges after Marlboro. And there would be at least the idea for yet another, to be called Robert Frost College (yes, really) that “never made it out of his briefcase,” as Dick Judd, with his dependably Yankee succinctness, once framed it for me. But that is, as they say, another story.

•••

Arthur Whittemore was a Boston attorney and later Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court judge who gave firm grounding to Walter Hendricks’ visionary idealism in ways that made the whole enterprise practical. From purchasing the necessary buildings and land that would complete the campus to paying faculty salaries out of his pocket during the lean years of the 1950s, he helped make Marlboro viable initially, and he would continue to do so for an additional two decades, all because of his unwavering faith. Tom Ragle, president emeritus, once paid tribute to him with the following words:

When Marlboro couldn’t pay its bills, he believed. When Marlboro held only 30 students, he believed. When the trustees had to meet monthly to ascertain whether the college could stay open another month, he believed. When people questioned the worth of a little place such as this, he believed.

He led the board for twenty years. His practical experience serving as Hingham, Massachusetts’ town meeting moderator helped him to see possibilities for community government at Marlboro, anticipating, as the first catalog states, “that students will form the habit of taking part, learn the strengths and weaknesses of the democratic process, and appreciate their own responsibility for its success.” Marlboro students over the years did indeed form the habit of taking part, as the college’s Town Meeting became central to the school’s identity. Arthur Whittemore’s conviction in the worth of democracy was derived from his innate sense of fairness and justice, ideals he lived by every moment of his public life.

•••

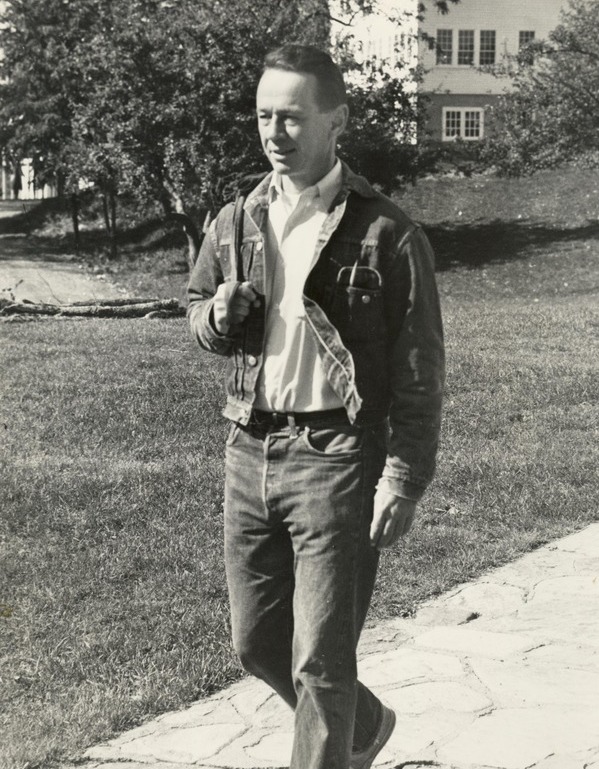

If there was a single individual over the course of Marlboro’s history who more than anyone embodied the college, it would be Roland Boyden. He served Marlboro as dean, faculty member (whose specialty was English history but who could and did teach anything), trustee, and twice acting-president. But also in other roles too numerous to count, summing it up once self-effacingly as “academic odd job man,” all this while taking—perhaps it can be said now—a dollar a year as his salary. Shortly after Roland’s death in 1981, trustee Paul Olson read a motion in his memory at a board meeting. Here is a portion of it:

Fortunate are the legion of Marlboro students who found Roland Boyden at the other end of the log. Fortunate too was the board of trustees. In the days before student and faculty representatives he was the sensitive ear and the all-encompassing eye that brought to the Board the many undercurrents of thoughts and feelings on the campus. For many years he somehow magically convinced the faculty that there were certain intangible rewards to teaching at Marlboro that made up for the lack of dollars in the budget and the perversity of Vermont weather.

Roland was a revered, much loved, and many-storied man, and among the most revealing stories is one that Tom Ragle recounts in Marlboro College: A Memoir. Tom was speaking at a faculty meeting about a student wanting to do a Plan in Ethiopian history, making it clear that allowing it to proceed was not possible, as there was no faculty member who was an expert on Ethiopian history and therefore no one qualified to sponsor a Plan on the subject. When Tom ended his talk, there was an expectant silence. Then Roland, with his characteristic reserve, said quietly, “I am.” Roland sponsored the student’s Plan, and the student, whose outside examiner came from the State Department, finished with an A level grade and in the years following would earn a doctorate in sociology. Roland’s humility was the singular strength that underpinned all that he was.

•••

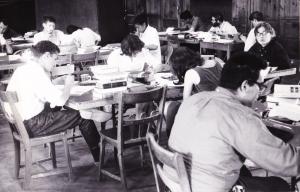

Tom Ragle’s presidency brought with it a measure of financial stability, a healthy influx of students, an enlarged faculty, a considerable expansion of the physical plant, and—in 1965—accreditation. It also brought into being the hallmark of Marlboro’s academic program, the Plan of Concentration. The scaffolding for it was already in place when Tom arrived in 1958—Marlboro’s introductory and general education courses leading to the Comprehensive Examination had, in the mid-1950s, been adapted to Marlboro from Black Mountain College by Roland. But Marlboro’s two final years, in Tom’s view as a young president, lacked “sufficient depth” and “an adequate climax.” He looked to his own student years at Harvard and Oxford as inspiration for what those final years might become, and he found it there. While the Plan was his conception, by the time it was first implemented in the fall of 1960, the entire faculty had a voice in what it would be.

In his memoir, Tom states that as college president, “I never ceased to think of myself as primarily a teacher, as a first among equals, and I believe I was treated that way.” True as this may be, the impression his book offers is that of a man over the course of 23 years absorbing, appreciating, and arriving at deep understandings of those around him and of what the college was becoming, in a word: learning. Tom’s presidency serves to remind us that in life there is no teaching without learning, and no learning without teaching regardless of which end of the log you happen to be sitting on, and that both are necessary when committing oneself to the stewardship of an evolving ideal.

•••

When l think of Arthur Whittemore, Roland Boyden, Tom Ragle, and others from the early years, these words come to mind: humility, kindness, largesse, loyalty, fairness, humor, erudition, integrity, and wisdom. Taken together these virtues came to be values ingrained in the school itself, and so in that sense the Frostian ideal of “spirit in substantiation” continued well beyond the college’s founding. It was the inimitable and insightful first treasurer of the board of trustees, Zee Persons, who put it simply: “Marlboro is people.” What we remember of the outward examples of those people and others can, down to the present moment, be life-giving and life-changing.

•••

In the days and years to come, if someone asks what I learned when I was a student at Marlboro College, I will say that I was taught to be humble and kind, that I was taught to be free in giving and tolerant and accepting of those different from me. I was also taught to speak honestly and to treat people fairly, and to see humor as a means of coping with things outside my control. I will say that I developed such a passion for learning that I have come to regard it as tantamount to breathing. That I was taught these things over breakfast and in seminar classes, while shoveling snow and while scrubbing the Dining Hall floor, in the serenity of the surrounding woods and in the quiet of the library. I will say that I was privileged in being shown, in myriad ways more implicit than explicit, that I mattered, that my presence at Marlboro was necessary and so it would be in the larger world as well.

I will say that in the time I was a student, I was only beginning to understand these things, but I as I grew older, that understanding deepened. And I will say that I am still working through all that I was given on that beautiful Vermont hillside, and with each emerging realization comes more cause for gratitude.

Then if the person says to me, “That must have been a very special place,” I will reply, “Believe me, it was.”

Dan Toomey has taught writing and literature at Landmark College for 35 years, and has written several article on Marlboro’s history for Potash Hill, most recently a biography of eminent ecologist Robert MacArthur ’51 in the Summer 2013 issue. He serves on the executive board of the Robert Frost Society and in 2021 will become its president.