Summertime at Villa Roma

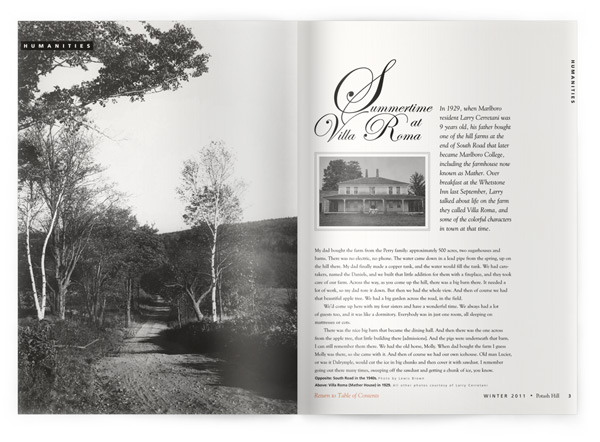

In 1929, when Marlboro resident Larry Cerretani was 9 years old, his father bought one of the hill farms at the end of South Road that later became Marlboro College, including the farmhouse now known as Mather. Over breakfast at the Whetstone Inn last September, Larry talked about life on the farm they called Villa Roma, and some of the colorful characters in town at that time.

My dad bought the farm from the Perry family: approximately 500 acres, two sugarhouses and barns. There was no electric, no phone. The water came down in a lead pipe from the spring, up on the hill there. My dad finally made a copper tank, and the water would fill the tank. We had caretakers, named the Daniels, and we built that little addition for them with a fireplace, and they took care of our farm. Across the way, as you come up the hill, there was a big barn there. It needed a lot of work, so my dad tore it down. But then we had the whole view. And then of course we had that beautiful apple tree. We had a big garden across the road, in the field.

We’d come up here with my four sisters and have a wonderful time. We always had a lot of guests too, and it was like a dormitory. Everybody was in just one room, all sleeping on mattresses or cots.

There was the nice big barn that became the dining hall. And then there was the one across from the apple tree, that little building there [admissions]. And the pigs were underneath that barn. I can still remember them there. We had the old horse, Molly. When dad bought the farm I guess Molly was there, so she came with it. And then of course we had our own icehouse. Old man Lucier, or was it Dalrymple, would cut the ice in big chunks and then cover it with sawdust. I remember going out there many times, sweeping off the sawdust and getting a chunk of ice, you know.

It was a beautiful field all the way down to the woods. We used to walk that way, go down and follow the brook, go way down to Harrisville [at the bottom of Moss Hollow Road], and then come back on the road. My dad would always have company up there, and we’d do that walk every so often. Some of the people we took there were, you know, they never did much walking. It would take us a few hours.

![]()

Henry Hughes had the adjoining farm, and his wife was a schoolteacher. Taught in the little schoolhouse next to Russell Hertzburg’s [now President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s house]. She was a big, strapping woman, and she was barefoot all the time. Went into the barn, all over the cow droppings and everything. Didn’t bother her one bit. We’d get milk from them. Nice fresh milk. So we had a nice relationship with them. Henry did a lot for my dad. I can still see him out there with his scythe, cutting down hay in the field and giving it to the horses and cows.

Down the road was Reverend Christie. Just down the bottom of the hill. From there, you came up the road to the Hertzburgs. Mr. Hertzburg would walk up the hill and sit on the porch with my dad, and they would have a wonderful time talking about different things. He was a painter; he had a paint store in Brattleboro.

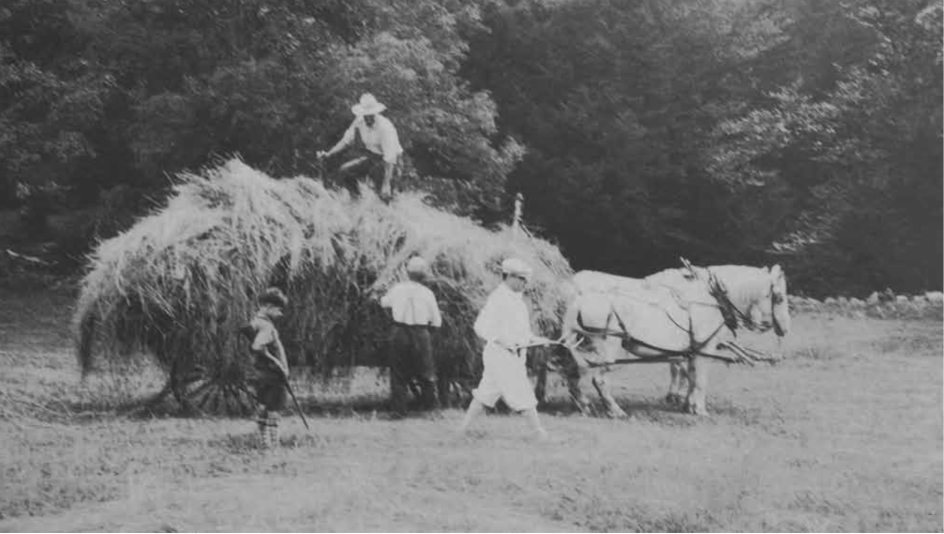

Then Lucier Road had Mr. and Mrs. Lucier and son Robert. Mr. Lucier was a violinist. Above them lived the Chase Brothers, Fred and Frank. They mowed our field for hay. Frank had just a little mustache, but Fred had a beard, and they were short people. At noon-time, Fred would sit down on the grass there, near that barn that’s near the road, across from the apple tree, and have lunch: a can of beans, a hunk of cheese and bread. Oh boy, what a guy he was. We used to get over a hundred-some tons of hay, between the upper field and the lower field. I helped with the haying. And Mrs. Hughes, I can remember her on the horse and wagon. Helen would throw the hay up, and Henry would pack it down on the wagon. It was all loose. Always put it right in the barn there. It was quite a thing.

Up in back of the house, there were two sugarhouses. It was just beyond that-you know, all the woods up there-Helen Hughes always said there’s an underground prison for the Indians. It was a cave-not a cave but a dungeon-like-went back to the 17- or 1800s maybe. Mrs. Hughes said it’s somewhere up there, all built with stone, just a hole in the ground. It must still be there. I had an idea where the area was, but I could never find it.

![]()

South Road was all dirt, and this wide. It was a bumpy and narrow road-and muddy, I’m telling you. If you met a car you had to find a spot to back up and pull over. The old road would get so muddy, my dad got stuck in the mud. My dad always had a big car, a big Cadillac I guess it was; he had just bought my mom a new Persian coat. And so we got stuck and we’re pushing the car. My mom’s pushing the car in her new coat. The car went ahead and my mom went down in the mud [laughs].

There was a little bridge right there before you make the turn at where Lucier Road takes off. It was all wood planks. And you’d go “buddaboom-buddaboom.” When company was coming, we could hear the bridge, “buddaboom-buddaboom,” up at the farm. After you crossed it, you’d stop and put the planks back, because they’re all loose.

We’d come up for winter for snow and stuff, but not too much. I spent some winters up here. Mrs. Hughes had a Morgan horse named Jack, and she’d hitch him up on a sleigh and we’d come up the road. And in the summer she’d come in a wagon.

We used to go to South Pond, go through the woods there, behind. Bob Lucier took care of horses for summer people. He and I would ride over there-go through the woods-or go down to Harrisville through the woods and then come back Moss Hollow Road. We’d go down to that little store down there and get Mule’s Head Beer. And we’d come back on the road, because it would be dark. It was bumpy and, I’ll tell you, full of ledge and rock. They’ve fixed it up beautifully now.

![]()

Walter Hendricks came into the picture in the late ’30s. He came in from Chicago with his whole family. It took about four days to drive out here. The kids were all small. I forget how many children he had, four or five kids. And they were all little tots. A lovely family, and Walter was quite a guy. They bought Henry Hughes’ place next door, then bought our farm from my dad.

I went into the service in ’42, until ’45. When I came out, Hendricks talked to my dad about selling the farm for the college. And that had to be ’46 or ’47. Hendricks would go down to New York to get money from different organizations. And he’d stop by to see my dad and visit. And of course, my dad was always writing a nice little check for him. He did that two or three times, I remember. From what I remember, when we sold I think the price was around $12,000. But my dad donated some money to the college too, because he was that type of person. My dad thought the idea of the college was a wonderful thing; that’s why he did that.

Joining Larry at breakfast was innkeeper Jean Boardman, local resident Gussie Bartlett (wife of Bob Bartlett ’52), alumni director Mark Genszler ’95, sophomore film student Jesse Nesser, Potash Hill editor Philip Johansson, and alumni Bruce and Barbara Cole ’59, who helped organize the event.

Anyone who thinks pastoral poetry is all rosy landscapes and butterflies should read their Virgil. Amanda Whiting ’11 found a window into the confused and sometimes bloody legacy of land reform in republican Rome, beginning with Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus in the first century B.C. “Their attempts at land redistribution not only sparked a huge shift in the way the political system dealt with land, but were also symptomatic of the pressures that caused Rome’s development from a republic into an empire,” said Amanda. Her Plan is a combination of literature and history, including translations of pastoral poetry from ancient Greek and Latin. “The herdsmen of Virgil’s Eclogues, many decades after the Gracchi had been killed, were still suffering from the effects of the failed program of agrarian reform.”

Anyone who thinks pastoral poetry is all rosy landscapes and butterflies should read their Virgil. Amanda Whiting ’11 found a window into the confused and sometimes bloody legacy of land reform in republican Rome, beginning with Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus in the first century B.C. “Their attempts at land redistribution not only sparked a huge shift in the way the political system dealt with land, but were also symptomatic of the pressures that caused Rome’s development from a republic into an empire,” said Amanda. Her Plan is a combination of literature and history, including translations of pastoral poetry from ancient Greek and Latin. “The herdsmen of Virgil’s Eclogues, many decades after the Gracchi had been killed, were still suffering from the effects of the failed program of agrarian reform.”