Outsiders: The Art of Joseph Beuys

By Tim Segar

At student orientation last August, art professor Tim Segar welcomed new students on behalf of the faculty with an informal talk about the nature of skepticism, doubt, and the character of welcome. In this excerpt, Tim continues…

Does the notion of “welcome” to an institution like Marlboro contain the familiar game of insiders beckoning to outsiders, challenging new students to join them, to separate themselves—to change their stripes? At a gathering of alumni this summer, I heard this very suspicion when I asked a group of former students how they had responded to their first few days on campus. The problem, they said, was how to overcome just this kind of skepticism and doubt, how to make the transition from outsider to insider without losing their judgment. Put another way, they found it hard, at first, to stay curious.

The flow from outsider to insider status may just be the way of the world. In his seminal essay “The Theory-Death of the Avant Garde,” Paul Mann argues that the inevitable path of innovative outsiders, beckoned or not, is from the margins toward the center of culture. Paradoxically, it is their very challenge of the center that makes them eligible, eventually, for inclusion there. Think of all the people who were once dismissed as nuts whose works now occupy the canons of music, art, science, and literature. Socrates, Galileo, Jung, Picasso, Stravinsky, The Clash. There are many examples of artists I could focus on, but I will share one.

Joseph Beuys was a German artist who lived from 1921 to 1986. His performance called How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare was made in 1965, when he was almost entirely unknown. Visitors could view Beuys through a window, where they found him sitting and cradling a dead hare in his arms. The artist’s face was covered in honey and gold leaf, and his boot was weighed down with an iron slab. He mumbled barely audible noises into the ear of the inert animal, as well as explanations of his drawings hanging behind them. This action, both strangely hilarious and moving, puts us in mind of the impossibility of teaching, the skepticism of listeners, indeed the deaf ears of most of those we ask to listen. It speaks to the difficulty of making one’s work known in the world and the possibility of an unexpected transcendence of these limits.

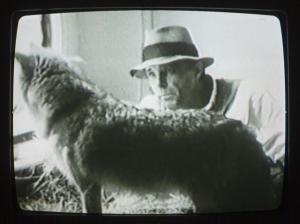

Beuys called pieces like these “actions.” A later example was I Like America and America Likes Me. In May 1974, Beuys flew to New York City and was taken to a room in a gallery on West Broadway, the site of the performance. He was transported by ambulance, lying on a stretcher and wrapped in felt. For three days, the artist shared the room with a wild coyote. Some of the time he stood leaning on a shepherd’s staff, swathed in his felt blanket. Other times he lay on a bed of straw and watched the coyote. The coyote watched him, circled him, and shredded his blanket to pieces. The artist did things like striking a large triangle, drawing lines on the floor, and other mysterious gestures. As Uwe Schneede describes in his book Joseph Beuys: Die Aktionen, “The performance continuously shifted between elements that were required by the realities of the situation, and elements that had purely symbolic character.”

After three days, the coyote had grown quite tolerant of Beuys. The artist hugged him and returned to the airport in an ambulance, leaving without having set foot on American soil. As Beuys later explained: “I wanted to isolate myself, insulate myself, see nothing of America other than the coyote.” A bit of context to remember is that the Vietnam War was in its last year when this piece was made, President Nixon was on the verge of resigning the presidency, and the international community had been looking askance at the United States for quite some time.

In both works, Beuys is acting on our behalf both humorously—mocking our attempts to interact with the world—and shamanically—conjuring hidden languages with which to cross the boundaries of death, species, language, and cultural divides. Are we meant to trust him? Should we take his play as serious or foolish? Does skepticism take hold? When I first saw these pieces, it did for me.

As a survivor of the Second World War, during which he fought as a pilot, Beuys later created his own account of his experiences that was largely mythical. After a crash, he claimed to have been wrapped in fat and felt and healed of his injuries by a tribe of Tartar nomads. Was this an invention in the service of art? Beuys said he was looking for a way for himself and for Germany to get past the ghosts of the Second World War. He sought a personal, artistic, and political practice that he called Social Sculpture—not all of which was what we might think of as sculpture. He made drawings, installations, machines, and three-dimensional forms along with his performative work. He had a deep respect for the symbolic story-telling of tribal people and for what he called “the significant lives of animals.” He was deeply influenced by the teaching of Rudolf Steiner and, like Steiner, he believed in an objective, intellectually comprehensible spiritual world accessible through direct experience.

Yet his was a tenuous position, as many people found his work inscrutable, overblown, offensive, or just silly. Despite growing interest from a group of devoted students, he was fired from his teaching job in Düsseldorf, though he continued to teach in his former classrooms until he was evicted. “Teaching is my greatest work of art,” he said. “The rest is the waste product, a demonstration.” His teaching lives on here and elsewhere in the growing inclusion of the political in the artistic world. A phrase of his that I still use in drawing class today goes, “Drawing is thinking: thinking is form.” Beuys labored in opposition to much of the skeptical art world, and he died a controversial, almost cult figure assailed by critics and artists alike. Since his death, his reputation has grown immensely, and he has come to be deeply revered by posterity.

Like many artists before and since, Beuys exemplifies a victory of action and curiosity over doubt and indifference, but also embodies the possibility of acting in more than one realm. He combined theater, art, politics, and anthropology. There are many ways of knowing, and the work of the faculty and students of Marlboro represents a wide range of these modes. Many students find inventive ways of combining these in interdisciplinary work. One reason I chose Beuys is that his breadth of action reflects a way to learn. I can’t expect all Marlboro students to include art in their studies here, though I hope I am forgiven for trying. I can expect all of them to find many avenues past their doubt.

That our acts are essentially optimistic is a central quality of Marlboro College. There is no real reason for us to expect that our work will succeed, affect others, or spread, especially when we are ourselves full of doubt. Is there a chance that we can “explain pictures to a dead hare?” How do we maintain optimism and curiosity and also employ our skepticism and doubt? Can we resist the pull of center and be both an insider and an outsider? Over their four years at Marlboro, students present work that asks similar questions, no matter whether they are working with equations or essays, ecology or economics.

The progression from outside to inside has sped up in recent years to light speed, due, I think, to the rapid spread of information and to a cultural appetite for newness that is insatiable. But for new students at Marlboro, the restraint they may feel is not just a question of how to hang on to their closely held perspectives, experiences, feelings, beliefs, and desires—what, in some classes at least, they will hear called subjectivity. It is also a question of how to measure those things against the invitation they are receiving daily to join something other than that, something that has momentum and energy, rights and wrongs of its own. My advice to students is to keep their suspicion. Be skeptical—it has an honorable place in the history of thought—just don’t let it overwhelm curiosity. The experience of students here at Marlboro gives us ample evidence of the transformation this will invite.

Tim Segar teaches sculpture and drawing at Marlboro and has exhibited his work widely, including last year’s regional Juror’s Choice Competition at the Thorne-Sagendorph Art Gallery, Keene State College. Tim is indebted to the description of Beuys’ pieces in Uwe Schneede’s book Joseph Beuys: Die Aktionen.

Performing presence and absence

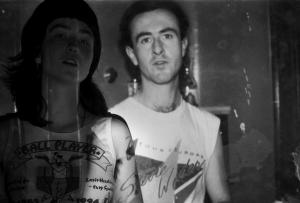

“I would consider my work to be ‘performance to camera,’ in that I use

photography and video as a tool to document live performances that are

done in private for the camera,” said senior Hannah Cummins. “These

images are then presented, or videos are installed.” She is working on a

Plan of Concentration in art, specifically performance art, photography,

and video dealing with notions of presence and absence, family, memory, time, and place. Hannah began her time at Marlboro delving deep to sociology, especially feminism, queer theory, and race/class/gender studies, and she is applying all of these foundations to her artwork. “My hope is to create work that is not only personally pertinent, but also politically conscious and engaged.” She is interested in education and is interning at the In-Sight Photography Project, in Brattleboro.

“I would consider my work to be ‘performance to camera,’ in that I use

photography and video as a tool to document live performances that are

done in private for the camera,” said senior Hannah Cummins. “These

images are then presented, or videos are installed.” She is working on a

Plan of Concentration in art, specifically performance art, photography,

and video dealing with notions of presence and absence, family, memory, time, and place. Hannah began her time at Marlboro delving deep to sociology, especially feminism, queer theory, and race/class/gender studies, and she is applying all of these foundations to her artwork. “My hope is to create work that is not only personally pertinent, but also politically conscious and engaged.” She is interested in education and is interning at the In-Sight Photography Project, in Brattleboro.