Tale of Two Churches: Conquest and Reconciliation in Ameca

By Rosario de Swanson

In 2012, Spanish professor Rosario de Swanson traveled to Ameca, Mexico, to learn about two of the town’s most important churches and the role of religion in local history.

Ameca is a small, provincial city in the state of Jalisco that is famous for its religious devotion, celebrations, and pilgrimages. It is also the town of my childhood and formative years, where I have cherished memories and strong family ties. In 2012, I returned to Ameca to conduct a long-awaited research project. Although Ameca used to be a small town, today the city has long outgrown its traditional limits, with sprawling neighborhoods swallowing up historic ranches. There is even a university campus in the outskirts, where there used to be a hamlet. But Ameca is still surrounded by its beautiful maize and sugar cane fields, and is still moved by the sounds of the ingenio de azúcar, or sugar mill, and of church bells calling the faithful to mass.

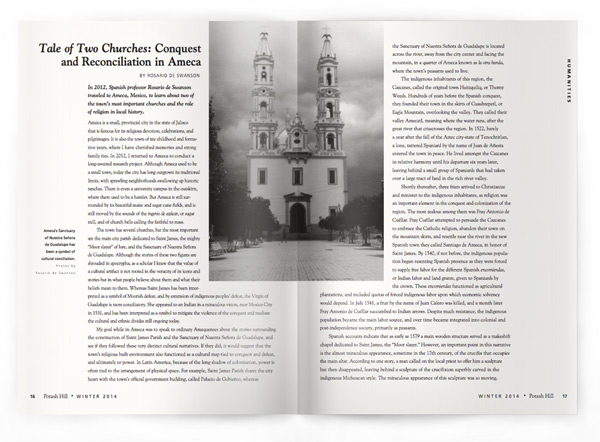

The town has several churches, but the most important are the main city parish dedicated to Saint James, the mighty “Moor Slayer” of lore, and the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Although the stories of these two figures are shrouded in apocrypha, as a scholar I knew that the value of a cultural artifact is not rooted in the veracity of its icons and stories but in what people believe about them and what their beliefs mean to them. Whereas Saint James has been inter preted as a symbol of Moorish defeat, and by extension of indigenous peoples’ defeat, the Virgin of Guadalupe is more conciliatory. She appeared to an Indian in a miraculous vision, near Mexico City in 1531, and has been interpreted as a symbol to mitigate the violence of the conquest and mediate the cultural and ethnic divides still ongoing today.

My goal while in Ameca was to speak to ordinary Amequenses about the stories surrounding the construction of Saint James Parish and the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, and see if they followed these very distinct cultural narratives. If they did, it would suggest that the town’s religious built environment also functioned as a cultural map tied to conquest and defeat, and ultimately to power. In Latin America, because of the long shadow of colonization, power is often tied to the arrangement of physical space. For example, Saint James Parish shares the city heart with the town’s official government building, called Palacio de Gobierno, whereas the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is located across the river, away from the city center and facing the mountain, in a quarter of Ameca known as la otra banda, where the town’s peasants used to live.

The indigenous inhabitants of this region, the Cazcanes, called the original town Huitzquiliq, or Thorny Weeds. Hundreds of years before the Spanish conquest, they founded their town in the skirts of Cuauhtepetl, or Eagle Mountain, overlooking the valley. They called their valley Amecatl, meaning where the water runs, after the great river that crisscrosses the region. In 1522, barely a year after the fall of the Aztec city-state of Tenochtitlan, a lone, tattered Spaniard by the name of Juan de Añesta entered the town in peace. He lived amongst the Cazcanes in relative harmony until his departure six years later, leaving behind a small group of Spaniards that had taken over a large tract of land in the rich river valley.

Shortly thereafter, three friars arrived to Christianize and minister to the indigenous inhabitants, as religion was an important element in the conquest and colonization of the region. The most zealous among them was Fray Antonio de Cuéllar. Fray Cuéllar attempted to persuade the Cazcanes to embrace the Catholic religion, abandon their town on the mountain skirts, and resettle near the river in the new Spanish town they called Santiago de Ameca, in honor of Saint James. By 1540, if not before, the indigenous population began resenting Spanish presence as they were forced to supply free labor for the different Spanish encomiendas, or Indian labor and land grants, given to Spaniards by the crown. These encomiendas functioned as agricultural plantations, and included quotas of forced indigenous labor upon which economic solvency would depend. In July 1541, a friar by the name of Juan Calero was killed, and a month later Fray Antonio de Cuéllar succumbed to Indian arrows. Despite much resistance, the indigenous population became the main labor source, and over time became integrated into colonial and post-independence society, primarily as peasants.

Spanish accounts indicate that as early as 1579 a main wooden structure served as a makeshift chapel dedicated to Saint James, the “Moor slayer.” However, an important point in this narrative is the almost miraculous appearance, sometime in the 17th century, of the crucifix that occupies the main altar. According to one story, a man called on the local priest to offer him a sculpture but then disappeared, leaving behind a sculpture of the crucifixion superbly carved in the indigenous Michoacan style. The miraculous appearance of this sculpture was so moving, the priest decided to name the church El Señor Grande de Ameca. However, the church archives fall silent on details of the further construction of the parish until 1722, when there begin detailed monetary expenditures due to its construction, which continue up to the time of its completion in 1770. By then the devotion to the Christ of El Señor Grande de Ameca had grown considerably.

By contrast, the construction of the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe across the river began much later, well after independence from Spain. The sanctuary was initiated thanks to a petition made to the main parish priest by a lay brother, Leocadio Briceño, in 1873. It is important to note that Briceño was of mixed indigenous and European ancestry and that at this point, 50 years or so after independence from Spain, such people could not become full priests or even enter the church’s hierarchy, although they could serve and work as lay brothers. Given his mixed ancestry, it is hardly surprising that el leguito Leocadio Briceño, as the records identify him, intended to build a church that in some way validated and recognized the indig- enous roots shared by the town’s peasants, who had become its main labor pool. It is also not surprising that Briceño’s initial request met with ferocious resistance from the main parish, as it challenged the old parish’s religious authority and meant a great loss of tithe levied to its parishioners.

The license to build Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe was not granted until five years later, in 1878, when Briceño was instructed to collect the property and revenue necessary for such a temple among the possible faithful. After decades in construction, during which masses were already being celebrated, the death of el leguito Leocadio Briceño brought the work to a halt in 1911. Construction began again in 1925 and was interrupted once more by the Cristero Wars, when Catholics rebelled against the anticlerical policies of the Mexican government. The work appears to have continued uninterrupted from 1943 onwards, but the details of its completion are missing from the church’s archive. All this time the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in la otra banda was a dependency of the main parish. That finally changed in 1970, when Cardinal Don José Salazar López, Archbishop of Guadalajara and a native son of Ameca, responded to the growth of the congregation and its devotion to the virgin by making the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe independent from the main parish.

Today, although the main parish of El Señor Grande de Ameca is still associated primarily with the town’s elite and the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe with the town’s peasant roots, it would be difficult to say which of these two churches is more important. The feasts associated with each of them bring extraordinary revenue to the town’s coffers each year. In another surprising turn, a little more than ten years ago, an enterprising young priest raised funds to add a carved image of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the façade of the church originally dedicated to Saint James. Some opposed the modification on purely architectural grounds, but most Amequenses applauded the move, and now the carved image presides over the entrance of the church. Although its style is different and the color of the stone is not the same, it seems to bring the history of the town full circle.

Pilgrimages to the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe happen each year on December 12, and are regarded as the most representative of local culture, as they go back to our town’s indigenous roots. The Christ sculpture of El Señor Grande de Ameca seems to complement this mission, as it now calls for Ameca’s hijos ausentes (literally absent children, as the people who migrated to the U.S. are called) to remember our origins, and perhaps one day to return. In September 2013, the Christ sculpture embarked on a pilgrimage of its own, visiting Ameca’s hijos ausentes living in the United States and calling on them to demonstrate their faith and pride in being from Ameca. While many Mexicans living in the United States consider the Virgin of Guadalupe a mark of their diasporic identity, for Ameca’s hijos ausentes, affiliation with El Señor Grande de Ameca appears to be an important symbol of their distinct roots within the Mexican community in the United States.

Although today the inhabitants of Ameca regard both churches as their own, the stories encoded within the churches’ histories show that this seemingly peaceful coexistence was not always so. Our town’s geography functioned as a cultural map, where ethnicity and race were ultimately tied to power. As the above stories make clear, religion was intertwined with conquest and colonization, and indigenous resistance was also located within this spiritual and paradoxically violent domain. Nevertheless, for the moment at least, reconciliation seems to have won out, as El Señor Grande de Ameca parish, originally dedicated to Saint James, is now presided over by the image of the virgin and in some way complements her mission. While the Virgin of Guadalupe once mitigated indigenous loss due to colonization, now El Señor Grande de Ameca ministers to Amequenses who have been uprooted by immigration.

Rosario de Swanson teaches Spanish and Spanish-language literature at Marlboro, with a focus on women writers and the Afro-Hispanic diaspora. In September she presented a reading of her award-winning play, Metamorfosis ante el espejo de obsidiana (Metamorphosis before the Obsidian Mirror), in Whittemore Theater.

Creating national identities in the New World

Mexico’s legacy of colonialism has parallels in the united States, another multiethnic

nation born out of colonialism and the subject of senior Allen Iano’s Plan of Concentration.

“I’ve studied American history obsessively since I was about 4 years old,” said Allen. “I’m

fascinated by the connections between intellectual trends and economic/demographic change.” Allen is exploring the contentious nature of pluralism through examples of “native” attitudes toward others, from loyalists in the American revolution to urban immigrants at the turn of the century. He is intrigued by the struggle of outside groups to find their niche and by the formation of allegiances for mutual benefit. “My family includes elements from very different backgrounds, and I’ve lived in several different parts of the country, so American history is a way for me to better understand myself.”

Mexico’s legacy of colonialism has parallels in the united States, another multiethnic

nation born out of colonialism and the subject of senior Allen Iano’s Plan of Concentration.

“I’ve studied American history obsessively since I was about 4 years old,” said Allen. “I’m

fascinated by the connections between intellectual trends and economic/demographic change.” Allen is exploring the contentious nature of pluralism through examples of “native” attitudes toward others, from loyalists in the American revolution to urban immigrants at the turn of the century. He is intrigued by the struggle of outside groups to find their niche and by the formation of allegiances for mutual benefit. “My family includes elements from very different backgrounds, and I’ve lived in several different parts of the country, so American history is a way for me to better understand myself.”