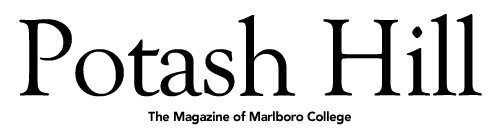

Jim Tober explores economics of retirement

“It was a simpler time in many respects, but I knew I wanted to come to a place like Marlboro even though I had never heard of Marlboro,” said economics professor Jim Tober, who joined the faculty in 1973. He described coming “somewhat accidentally,” sending an introductory letter before the college had even advertised the position. But it is no accident that Jim has stayed with Marlboro for 40 years, and made lasting contributions as a social sciences teacher, administrator, and mainstay of both environmental studies and the World Studies Program.

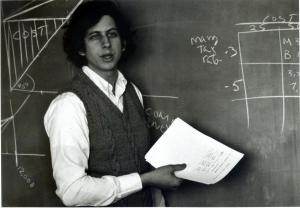

“Jim arrived my senior year at Marlboro,” said Peter Zamore ’74, an attorney and Marlboro trustee. “He was young, full of energy, and integrated well into the student body. He immediately experienced the essence of Marlboro—providing a solid education through creative use of limited resources.”

Jim came to Marlboro directly from his graduate program in economics at Yale University, where he did his dissertation on the political economy of wildlife conservation in 19th-century America, the subject of his first book. He was looking for a college that would welcome an interdisciplinary approach to economics, and found it in abundance here.

“I was something of an anomaly among economics graduate students in that I spent as much time as I could justify outside of the department, taking classes in anthropology, African studies, and at the forestry school,” he said. “The forestry school, in particular, embodied the kind of scholarly community that I found to my liking, where people of very different trainings shared a common concern, in this instance for natural resources and the environment.” He found the same kind of community in the Marlboro faculty’s shared commitment to interdisciplinary inquiry in the liberal arts.

Jim’s arrival at Marlboro was well timed in terms of the faculty’s desire to build both the social science area and environmental studies. He and colleagues devised and co-taught an introductory environmental studies course for a dozen years or so, beginning in the mid-1970s. He has continued throughout his Marlboro career to offer many environmental studies courses, including those on environmental eco nomics and policy, U.S. environmental history, land and land-use planning, endangered species (with biology professor Jenny Ramstetter), and wildlife law and policy. Jim was the first chair of the Environmental Advisory Committee, which advises the president on sustainability issues, and initiated the adoption of Marlboro’s Environmental Mission Statement. He organized a recent faculty retreat on environmental studies, and has been instrumental in a resurgence of that program.

Meanwhile, Jim’s passion for conservation has been an asset to the local community as well. He was a longtime member (and former chair) of the Marlboro Planning Commission, which guides development decisions in the town. He was also a board member of the Hogback Mountain Conservation Association during the acquisition of this town park property, and is now a member of the town commission governing its management. These activities supported Jim’s teaching on land use and environmental policy, providing practical, place-based case studies for students.

Eminently level-headed and comfortable in the role of administrator, Jim has held several administrative posts at Marlboro, starting with his very first year. He and his wife, Felicia, needed a place to stay, so they were offered an apartment in Random North if he served as dean of students, which he did for two years along with his teaching position. He also did a couple of terms as dean of faculty for a total of seven years, including two years during the crucial transition between presidents Paul LeBlanc and Ellen McCulloch-Lovell. Jim also served as the director of world studies in the early years of that signature program, and again in 1998–2000. “The World Studies Program was the impetus for several research trips, notably to look at wildlife management in Namibia and study the nonprofit sector in Bangladesh, that enlarged my global perspective and informed my teaching.”

But Jim still considers himself primarily a North Americanist when it comes to economics. His second book, Wildlife and the Public Interest: Nonprofit Organizations and Federal Wildlife Policy (1989), was based on his research on wildlife policy in the U.S. during a sabbatical year residency at the Yale Program on Nonprofit Organizations. This affiliation led to his teaching emphasis on the nonprofit sector, which has encouraged several undergraduate students to pursue Marlboro’s graduate and professional program on managing mission-driven organizations.

Over the years, Jim organized his teaching around two broad fields of inquiry, the analysis and comparison of economic systems and the history and development of public policy and collective decision-making, especially as related to the natural environment. He has always struggled with the orthodoxy within the discipline, and with the need to balance mainstream discourse with the range of topics and perspectives Marlboro students bring to the table.

“The standard American economics curriculum—as distinct from my Marlboro offerings—obscures significant disagreement and disarray within the discipline as to the value of this orthodox approach, broadly known as the neoclassical synthesis,” said Jim. “It has been a real challenge for me both to certify that Plan students of economics know what they ‘should’ know and to support them in exploring alternative—and often more useful and interesting—paradigms.” While few students arrive at Marlboro knowing that they want to study economics, many discover what the discipline offers once they are here, and this has provided Jim with generations of truly engaged students.

“Economics is known as the ‘dismal science,’ and I must admit I was hesitant to dive into the subject when I started thinking about Plan,” said Kelsa Summer ’13, who did her Plan of Concentration on the economics and politics of development and social change in Africa. “Jim helped me to see how economics can be intriguing, inspiring, and not so dismal after all. He gave me one of the important lenses through which I view the world, and I am very grateful for that.”

“Tutorial with Jim was precisely what Marlboro billed itself as when I first visited,” said Casey Freidman ’12, who did his Plan in the economics and politics of international relations, specifically U.N. food agencies. “Jim was an adept guide through intellectual worlds foreign to me, directing me to new, relevant ideas across a stunningly wide range of thought. He prompted me to clarify my own ideas, but the overarching direction of our examination was always my responsibility.”

Casey described feeling like part of a strange brotherhood of students who worked closely with Jim, “united by this enigmatic wise man.” He said, “It never took long for him to come up in conversation among us. There was often exegesis of his moods and reactions but the typical conclusion was ‘It’s Jim—there’s no knowing.’”

Jim is characteristically enigmatic about his retirement plans, although they will certainly include lots of gardening, traveling, writing, and, a recent fascination, ceramics. How he will focus his continued academic interests, or his quirky hobby of collecting panther TV lamps, there’s no knowing. But his legacy of inspired teaching will be remembered at Marlboro for some time.

“Great teachers don’t only teach you a subject matter; they teach you how to learn,” said Kelsa. “Jim is an expert at that. Some of my favorite hours at Marlboro were spent debating the fine points of economic development with Jim. He taught me how to peel away the layers of an issue, and showed me how in each hard question lies yet another one.”