Marlboro and the “Vermont Way of Life”

By David Amato ’14

The establishment of Marlboro College by founder Walter Hendricks was part of a much larger movement to construct a new identity in Vermont’s post-agricultural age.

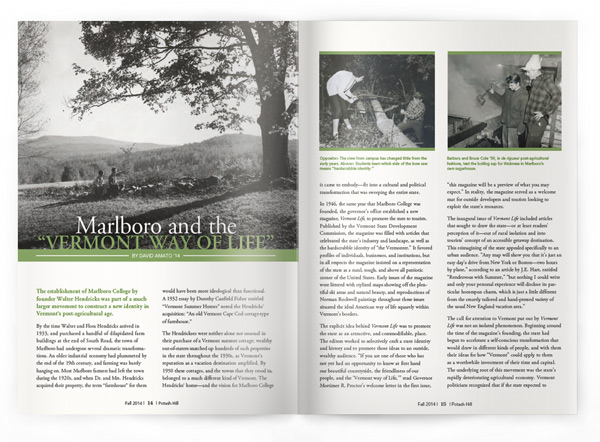

By the time Walter and Flora Hendricks arrived in 1933, and purchased a handful of dilapidated farm buildings at the end of South Road, the town of Marlboro had undergone several dramatic transformations. An older industrial economy had plummeted by the end of the 19th century, and farming was barely hanging on. Most Marlboro farmers had left the town during the 1920s, and when Dr. and Mrs. Hendricks acquired their property, the term “farmhouse” for them would have been more ideological than functional. A 1932 essay by Dorothy Canfield Fisher entitled “Vermont Summer Homes” noted the Hendricks’ acquisition: “An old Vermont Cape Cod cottage-type of farmhouse.”

The Hendrickses were neither alone nor unusual in their purchase of a Vermont summer cottage; wealthy out-of-staters snatched up hundreds of such properties in the state throughout the 1930s, as Vermont’s reputation as a vacation destination amplified. By 1950 these cottages, and the towns that they stood in, belonged to a much different kind of Vermont. The Hendricks’ home—and the vision for Marlboro College it came to embody—fit into a cultural and political transformation that was sweeping the entire state.

In 1946, the same year that Marlboro College was founded, the governor’s office established a new magazine, Vermont Life, to promote the state to tourists. Published by the Vermont State Development Commission, the magazine was filled with articles that celebrated the state’s industry and landscape, as well as the hardscrabble identity of “the Vermonter.” It favored profiles of individuals, businesses, and institutions, but in all respects the magazine insisted on a representation of the state as a rural, tough, and above all patriotic corner of the United States. Early issues of the magazine were littered with stylized maps showing off the plentiful ski areas and natural beauty, and reproductions of Norman Rockwell paintings throughout these issues situated the ideal American way of life squarely within Vermont’s borders.

The explicit idea behind Vermont Life was to promote the state as an attractive, and commodifiable, place. The editors worked to selectively craft a state identity and history and to promote those ideas to an outside, wealthy audience. “If you are one of those who has not yet had an opportunity to know at first hand our beautiful countryside, the friendliness of our people, and the ‘Vermont way of Life,’” read Governor Mortimer R. Proctor’s welcome letter in the first issue, “this magazine will be a preview of what you may expect.” In reality, the magazine served as a welcome mat for outside developers and tourists looking to exploit the state’s resources.

The inaugural issue of Vermont Life included articles that sought to draw the state—or at least readers’ perception of it—out of rural isolation and into tourists’ concept of an accessible getaway destination. This reimagining of the state appealed specifically to an urban audience. “Any map will show you that it’s just an easy day’s drive from New York or Boston—two hours by plane,” according to an article by J.E. Hart, entitled “Rendezvous with Summer,” “but nothing I could write and only your personal experience will disclose its particular homespun charm, which is just a little different from the smartly tailored and hand-pressed variety of the usual New England vacation area.”

The call for attention to Vermont put out by Vermont Life was not an isolated phenomenon. Beginning around the time of the magazine’s founding, the state had begun to accelerate a self-conscious transformation that would draw in different kinds of people, and with them their ideas for how “Vermont” could apply to them as a worthwhile investment of their time and capital. The underlying root of this movement was the state’s rapidly deteriorating agricultural economy. Vermont politicians recognized that if the state expected to proceed into the second half of the 20th century on solid economic footing, it would need to find new sources of revenue. Increased tourism was immediately identified as a possible solution.

But before this solution could be thoroughly explored, the state would require a major infrastructure overhaul. New construction projects, especially those centered on highway and road development, reflected and reproduced the social and economic transformations occurring in the state. Indeed, the transformation of Vermont’s landscape was inseparable from these broader phenomena. In 1955 governor Joseph Johnson sounded a cry for increased development: “I believe the state should extend a welcome hand to all corners of our nation so that people will be encouraged to come here. These folks spend money and this money makes jobs.”

This project of modernization and development occurred simultaneously with the conversion of Hendricks’ South Road properties into a liberal arts college. But land was not the only commodity that Vermont offered. At work in Vermont Life and, increasingly, in state politics, was a positioning of local against outsider, rural against urban, Vermonter against flatlander. The culture and residents of Vermont were being assimilated into charming tourist concepts, and this process extended to the new college in Marlboro. In 1949, Hendricks traveled to New York City with Luke Dalrymple, the carpenter entrusted with renovating old farm buildings into a new college. A reporter from the New York Times caught up with the pair to document their visit: “First Visit to New York Impresses Vermont Campus Sage,” the headline read, “but He Prefers Home Hills—Central Park Trees Just ‘Brush.’” The article summarizes Dalrymple as “a down-to-earth, native Vermonter, with a clipped Yankee twang and a dry sense of humor. He is a man of few words—a five or six word sentence is an oration for him.”

The transformation of Marlboro at mid-century thus fit into a larger economic and social movement occurring in the southern half of the state. The landscape of Vermont—in the span of only a few decades—had rapidly shifted from one of production to one of consumption. As a result of outside pressures, the state’s geography itself transformed into a readily consumable cultural product. The college was certainly not a tourist destination, a state park, or a ski resort, but it developed in a similar fashion and along lines similar to Vermont tourist sites. It stood as both a justification for and a beneficiary of the development projects that sought to modernize the state.

As in a Rockwell painting, iconic images played— and continue to play—a key role in mapping out the cultural significance of the college. And no human being was more iconic an image of the hardscrabble Vermonter than Luke Dalrymple. Like a Rockwell painting, the college was a fabrication of the land and buildings and people of Vermont, conjured from an obscure place and infused with patriotic and social meaning. The relevance of the college—indeed, the urgency of founding the college—was framed in the context of democracy in peril. “When democracy is threatened,” intoned Judge Arthur Whittemore at the college’s first commencement, in 1948, “it is increasingly realized that responsibility and participation are the concomitants of democracy’s blessings and it is such institutions as Marlboro which teach responsibility and participation.”

The “identity” of a place is never fixed. Rather, it is informed by competing ideals and representations filtered through the realities of history. In Vermont, this competition has been a constant aspect of the state’s history, especially with regard to the land, which various groups have laid claim to with different ends in mind for several centuries. This process has formed a large part of Marlboro College’s place in the state. Today, when students, faculty, and staff give off-the-cuff histories of Marlboro College, they almost always tell the same story of the farm turned into a college. It is a nostalgic story, one that places the college’s history in Vermont’s pastoral tradition. But really, Walter Hendricks’ “farm” was more of a vacation spot, secluded, less-than-notable to highway passersby, but a piece of local fabric, part of a landscape defined by rich history and memories.

Hendricks participated in a process, which further developed in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, of identifying the Vermont landscape as a virtuous canvas for expression and independence. By establishing a college in Marlboro, he engaged in a type of work that was occurring throughout the state in various forms, transforming it into something much different from an earlier state defined by agricultural decline. In the process, he opened the door for locals and new residents to arrive at their own definitions of the landscape and its meaning. These negotiations continue today, in towns like Marlboro and Brattleboro, in exchanges between neighbors, in the statehouse, and in the houses and barns converted by Luke Dalrymple.

David Amato graduated in May with a degree in American studies, urban history, and journalism. This article is adapted from his Plan of Concentration, which focused on how the culture and politics of the post–World War II era shaped the built environment. Read David Amato’s full Plan paper, “‘On the Road to Harrisville’: Local Transformation and the Construction of Identity in Marlboro, Vermont.”

Communicating National Identity in Cairo

In a place far from Vermont, but perhaps not so different from it after all, Emma Loftus ’14 explored what the built environment in and around Cairo says about Egypt’s evolving national identity. Emma did her Plan of Concentration in cultural history and urban studies, with field research in Cairo on the spatial impact of the policies of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. “I focus on the legacy of the ‘outward-oriented’ approach to urban planning and development,” says Emma. “The idea of ‘planning for lower-case-O other’ is pervasive in both current and historical contexts in Egypt. I became aware of the threat that this poses to urban public spaces and to the identities of people who inhabit them.” For example, Emma explores how Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square was designed by Nasser’s administration to project a secular national identity, “catering to an international audience and discouraging local and public culture.”

In a place far from Vermont, but perhaps not so different from it after all, Emma Loftus ’14 explored what the built environment in and around Cairo says about Egypt’s evolving national identity. Emma did her Plan of Concentration in cultural history and urban studies, with field research in Cairo on the spatial impact of the policies of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. “I focus on the legacy of the ‘outward-oriented’ approach to urban planning and development,” says Emma. “The idea of ‘planning for lower-case-O other’ is pervasive in both current and historical contexts in Egypt. I became aware of the threat that this poses to urban public spaces and to the identities of people who inhabit them.” For example, Emma explores how Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square was designed by Nasser’s administration to project a secular national identity, “catering to an international audience and discouraging local and public culture.”