Undergraduate Commencement 2014

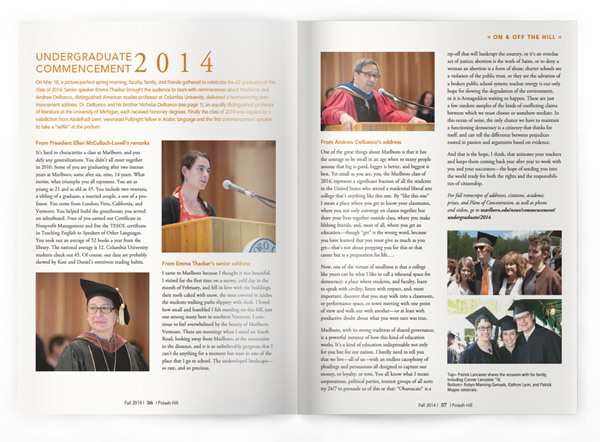

On May 18, a picture-perfect spring morning, faculty, family, and friends gathered to celebrate the 62 graduates of the class of 2014. Senior speaker Emma Thacker brought the audience to tears with reminiscences about Marlboro, and Andrew Delbanco, distinguished American studies professor at Columbia University, delivered a heartwarming commencement address. Dr. Delbanco and his brother Nicholas Delbanco (see page 1), an equally distinguished professor of literature at the University of Michigan, each received honorary degrees. Finally the class of 2014 was regaled by a valediction from Abdelhadi Izem, venerated Fulbright fellow in Arabic language and the first commencement speaker to take a “selfie” at the podium.

From President Ellen McCulloch-Lovell’s remarks

It’s hard to characterize a class at Marlboro, and you defy any generalizations. You didn’t all enter together in 2010. Some of you are graduating after two intense years at Marlboro; some after six, nine, 14 years. What stories, what triumphs you all represent. You are as young as 21 and as old as 45. You include two veterans, a sibling of a graduate, a married couple, a son of a professor. You come from London, Peru, California, and Vermont. You helped build the greenhouse; you served on selectboard. Four of you earned our Certificate in Nonprofit Management and five the TESOL certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. You took out an average of 52 books a year from the library. The national average is 12. Columbia University students check out 45. Of course, our data are probably skewed by Kate and Daniel’s omnivore reading habits.

From Emma Thacker’s senior address

I came to Marlboro because I thought it was beautiful. I visited for the first time on a snowy, cold day in the month of February, and fell in love with the buildings, their roofs caked with snow, the trees covered in icicles, the students walking paths slippery with slush. I loved how small and humbled I felt standing on this hill, just one among many here in southern Vermont. I continue to feel overwhelmed by the beauty of Marlboro, Vermont. There are mornings when I stand on South Road, looking away from Marlboro, at the mountains in the distance, and it is so unbelievably gorgeous that I can’t do anything for a moment but stare in awe of the place that I go to school. The undeveloped landscape— so rare, and so precious.

From Andrew Delbanco’s address

One of the great things about Marlboro is that it has the courage to be small in an age when so many people assume that big is good, bigger is better, and biggest is best. Yet small as you are, you, the Marlboro class of 2014, represent a significant fraction of all the students in the United States who attend a residential liberal arts college that’s anything like this one. By “like this one” I mean a place where you get to know your classmates, where you not only converge on classes together but share your lives together outside class, where you make lifelong friends, and, most of all, where you get an education—though “get” is the wrong word, because you have learned that you must give as much as you get—that’s not about prepping you for this or that career but is a preparation for life….

Now, one of the virtues of smallness is that a college like yours can be what I like to call a rehearsal space for democracy: a place where students, and faculty, learn to speak with civility, listen with respect, and, most important, discover that you may walk into a classroom, or performance space, or town meeting with one point of view and walk out with another—or at least with productive doubt about what you were sure was true.

Marlboro, with its strong tradition of shared governance, is a powerful instance of how this kind of education works. It’s a kind of education indispensable not only for you but for our nation. I hardly need to tell you that we live—all of us—with an endless cacophony of pleadings and persuasions all designed to capture our money, or loyalty, or vote. You all know what I mean: corporations, political parties, interest groups of all sorts try 24/7 to persuade us of this or that: “Obamacare” is a rip-off that will bankrupt the country, or it’s an overdue act of justice; abortion is the work of Satan, or to deny a woman an abortion is a form of abuse; charter schools are a violation of the public trust, or they are the salvation of a broken public school system; nuclear energy is our only hope for slowing the degradation of the environment, or it is Armageddon waiting to happen. These are just a few random samples of the kinds of conflicting claims between which we must choose or somehow mediate. In this ocean of noise, the only chance we have to maintain a functioning democracy is a citizenry that thinks for itself, and can tell the difference between prejudices rooted in passion and arguments based on evidence.

And that is the hope, I think, that animates your teachers and keeps them coming back year after year to work with you and your successors—the hope of sending you into the world ready for both the rights and the responsibilities of citizenship.

For full transcripts of addresses, citations, academic prizes, and Plans of Concentration, as well as photos and videos, go to the Marlboro website.