Confluence

Sustainability requires gathering “tributaries of wisdom” and returning to a more ecologically enlightened relationship with the earth, says graduate faculty member Cary Gaunt.

By Cary Gaunt

The discharge pipe was just out of reach. By holding on to the branch of a draping willow tree I could almost position the beaker into the spewing effluent to get the sample needed for my research. Just when I was fully extended, the stream bank crumbled underfoot and I landed in the murky depths at the outfall of my hometown’s sewage treatment plant. Thus was my initiation into a lifelong vocation in sustainability. The year was 1977.

Long before sustainability became an overused and misaligned buzzword—named one of the “jargoniest jargon” words by Advertising Age magazine and dismissed as “sustainababble” by the former president of the World Watch Institute—I started tracking its elusive path.

My journey started with love. To my parents’ chagrin (or perhaps relief), instead of obsessing over high school dating rituals, I fell in love with a place. Abrams Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, ran through our farm in Virginia and became my constant companion and endless source of fascination. I turned over rocks in search of crawfish, concocted teas from the wildflowers along its banks, laid on my back in the shallows during torpid August days, and built rafts that never floated. Mine was a reciprocal relationship cultivated through all of my senses—I tasted, smelled, heard, touched, and witnessed seasonal cycles and daily flows. My childhood curiosity prompted so many questions, many that still direct me today.

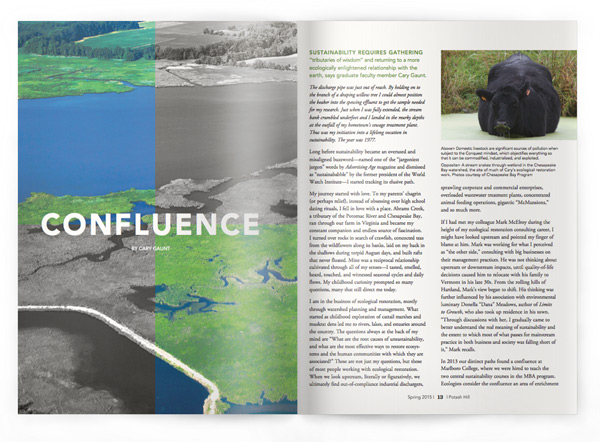

I am in the business of ecological restoration, mostly through watershed planning and management. What started as childhood exploration of cattail marshes and muskrat dens led me to rivers, lakes, and estuaries around the country. The questions always at the back of my mind are “What are the root causes of unsustainability, and what are the most effective ways to restore ecosystems and the human communities with which they are associated?” These are not just my questions, but those of most people working with ecological restoration. When we look upstream, literally or figuratively, we ultimately find out-of-compliance industrial dischargers, sprawling corporate and commercial enterprises, overloaded wastewater treatment plants, concentrated animal feeding operations, gigantic “McMansions,” and so much more.

If I had met my colleague Mark McElroy during the height of my ecological restoration consulting career, I might have looked upstream and pointed my finger of blame at him. Mark was working for what I perceived as “the other side,” consulting with big businesses on their management practices. He was not thinking about upstream or downstream impacts, until quality-of-life decisions caused him to relocate with his family to Vermont in his late 30s. From the rolling hills of Hartland, Mark’s view began to shift. His thinking was further influenced by his association with environmental luminary Donella “Dana” Meadows, author of Limits to Growth, who also took up residence in his town. “Through discussions with her, I gradually came to better understand the real meaning of sustainability and the extent to which most of what passes for mainstream practice in both business and society was falling short of it,” Mark recalls.

In 2013 our distinct paths found a confluence at Marlboro College, where we were hired to teach the two central sustainability courses in the MBA program. Ecologists consider the confluence an area of enrichment that occurs at the meeting place of contrasting habitats. When waters from two different sources flow together, for example, the resulting nutrient soup often provides immensely fertile habitat. Wisdom teachers also note the creative ferment of the confluence, or “middle way.”

Marlboro is a place imbued with smart and engaged students, who asked for clarity amidst a world of “sustainababble.” From the confluence of our distinct perspectives, and with the skillful facilitation and wisdom of two other colleagues on the MBA faculty, Bill Baue and Pat Daniels, we created the Sustainability Continuum, a business leadership framework that explains the evolution of sustainability and its important normative developments.

The Sustainability Continuum identifies six distinct phases of sustainability thought and practice (see figure, right). Although presented as a chronology, we consciously shaped the continuum as a circle to reflect the evolutionary emergence of sustainability consciousness and action, its relationship to ecological cycles and goals of wholeness, and to indicate the actual and desired direction for its unfolding. The trajectory is neither stepwise nor linear. Rather, many of the stages presented in the continuum occur concurrently. Individuals, organizations, and businesses can locate themselves on the continuum and use its framework for sustainability planning and action. It has already proven to be an excellent tool for organizing our curriculum, and teachers throughout the MBA program are using it in their classes.

We initiated the Sustainability Continuum in the deep past, what we call the Kinship stage, where humans were deeply embedded in their places and connected to the natural world in relational and participatory ways, often in accord with ecological cycles. This stage represents an indigenous way of knowing, described by Native American educator and Tewa Indian Gregory Cajete as one that is rooted in place and based on “the perception gained from using the entire body of our senses in direct participation with the natural world.” It is far broader than the narrow view of Western science and business management, because it includes spirituality, community, creativity, and dynamic participation with the natural world based on an ancient covenant. While some have called into question the environmental practices of ancient cultures, indigenous worldviews based on principles of participation, relationship, interdependence, animism, and kinship comprise a “perceptual wisdom” that is essential for sustainability.

The foundation for many of today’s unsustainable ways surfaced in the Conquest stage, which describes the shift away from interdependence with nature toward exploitation of nature—in which previously sacred relationships became commoditized and privatized, and the natural world became reduced to smaller and smaller parts suitable for study and sale. This period was marked by increased alienation from the natural world, a growing anthropocentric worldview, organized and aggressive colonialism, and the advent of consumerism, including the growth and extractive economies we still have in place today. This is arguably the stage where most businesses and MBA programs focus their emphasis in order to bolster the bottom line and shareholder profits—it is discouraging how many examples of this stage are at work today. We make our students aware of them, but consciously emphasize a new way of doing business.

One summer day in 1969, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River began to burn, capturing the attention of a nation waking up to the serious and palpable damages caused by a rampant Conquest stage of human activity. A month later, Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. Images of earth from space showed for the first time the boundaries of a finite planet. The confluence of these memorable events, and many more, sparked the dawn of a formal U.S. environmental movement—on April 22, 1970, the first Earth Day celebration was held, and later that year the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed.

We mark the Mitigation stage by the establishment of regulatory controls and the rise of eco-efficiency concepts and adaptation initiatives based largely on engineering and other technological approaches. The creation of the EPA was symbolic of this era, and was heralded by a creative burst of environmental regulations—the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Ocean Dumping Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Energy Policy and Conservation Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, and the Superfund Program—all in the first decade.

The emphasis of these important efforts was to reduce and/or adapt to the unwanted effects of consumerism by setting limits or increasing efficiency—steps in the right direction, but still not sustainability in the more rigorous sense of the term. My predecessor at Marlboro, sustainability thought leader John Ehrenfeld, sees these efforts as “merely a Band-Aid that masks deeper, cultural roots of our sustainability challenge.” In his seminal book Sustainability by Design, John writes, “Hybrid cars, LED light bulbs, wind farms, and green buildings, these are all just the trappings that convince us that we are doing something when in fact we are fooling ourselves and making things worse.”

I have experienced this disconnect between sustainability intention and result throughout my career, most recently as a consultant for the Boston Green Ribbon Commission. I was charged with assessing the progress of the city’s colleges and universities in achieving the ambitious carbon reduction goals of Boston’s Climate Action Plan. All of the schools were taking impressive steps, from building LEED-certified buildings to using sustainable food options for campus dining. Yet all of these were conducted in the shadow of growth. Each university was committed to growing its student population and campus size, effectively overwhelming its positive steps.

Despite decades of well-meaning mitigation efforts, the economics of growth and excess have created conditions where the nation as a whole is not achieving its sustainability goals. Environmental conditions continue to decline, and threats to our natural world appear to be relentless and expanding. People across sectors increasingly ask, “What’s next? How do we respond?” It is from this inquiry that the effort to develop sustainability metrics emerged.

What we call the Sustainability stage responds to the business adage “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” The Sustainability stage is where business practices revolve around the idea that there are social, economic, and environmental thresholds, locally and globally, that must be taken into account when attempting to manage or assess the effects of human activity. “Authentic sustainability” will only occur when resource use or waste generation are measured against clearly defined place-based limits, such as the amount of water in local aquifers, or the amount of carbon the atmosphere can safely absorb.

“If you just look at the measurements of what you are doing and don’t tie it back to reality on the ground, in terms of resources that are available or the social investments that are necessary, then you’ve answered some questions,” says Mark McElroy. “But you haven’t answered the question of ‘are you sustainable?’” Mark had started working on measuring sustainability performance with his mentor Dana Meadows shortly before her death in 2001, and he decided to continue this work for his doctoral dissertation. He created a business-focused sustainability accounting system called Context-Based Sustainability (CBS), which has further evolved into the MultiCapital Scorecard (MCS).

With Mark’s support, two popular Vermont businesses are stepping out as leaders through their pioneering work implementing these sustainability metrics. Both Cabot Cheese and Ben & Jerry’s are using these approaches to “take sustainability literally,” by exploring actual resources used or impacted in manufacturing, such as water and climate, measured against what is truly available in their manufacturing areas and in their supply chains. In addition, they include a human component and consider factors such as livable wages, social activism, and gender parity.

Sustainability metrics are essential steps in the sustainability journey, yet something else is clearly needed—such was the conclusion of the 2003 Chesapeake Futures report, which provided a 20-year retrospective of restoration efforts and an ambitious look forward. While acknowledging the important contributions of conventional environmental protection approaches, the report concluded that we could not regulate, monitor, measure, or model ourselves out of the problem, or find a technological fix. The report called for the cultivation of a new ethic: the ecologically enlightened citizen.

I became seized by the underlying recommendation of the Futures report, because it captured my own beliefs and the central theme repeatedly heard in sustainability circles—how do we cultivate the ecologically enlightened citizen? It fueled a research inquiry that eventually became my doctoral dissertation and dramatically changed the trajectory of my work. I began shifting my gaze from the Mitigation and Sustainability stages to something much more difficult to quantify. I gathered tributaries of wisdom from sources that were new to me—psychology, religion, spirituality, and other humanities and social sciences—and some that were a homecoming, especially deep exploration of the natural world and contemplative traditions. Even more, I sought out the wisdom of lived experience from individuals who are ecologically awakened and committed to sustainability—leaders and ordinary citizens who modeled the kinds of changes we seek.

In Sustainability by Design, John Ehrenfeld calls these kinds of changes “sustainability-as-flourishing.” He describes them emerging from profound shifts in human consciousness and behavior, from a view of ourselves of “Having” to one of “Being,” from one of “Needing” to one of “Caring.” The sustainability role models I study for my research embody in many ways the new ethic John imagines. Of course they are intellectually engaged in the issues, from the science of climate change to the complexities of renewable energy. More, however, they speak of creating new stories of how to live and inhabit our places, and how to fit into the larger earth story.

These sustainability role models embody the Flourishing stage by spending time getting to know the resources and beings of their places, using all of their senses. They are gardeners, or participate in ecological restoration. Others are naturalists or artists informed by nature. All are explorers—intellectually curious and wanderers on the land. They use words like beauty, wonder, awe, and love to describe the earth and their relationship to it. Many consider the natural world to be imbued with spirit, and therefore sacred. By being deeply rooted in their places, they intuitively considered environmental and social thresholds in their decision making. They had, whether “born in the groove” like me on the banks of Abrams Creek or “converted later in life” like my colleague Mark McElroy, begun a return to the Kinship stage of sustainability consciousness and action, but with a modern approach.

The Flourishing stage demands a human relationship with place that is premised on reciprocity and embodied through actions that contribute more to the natural and human communities than they take from them. Flourishing enterprises might restore their grounds with locally generated organic compost and bee-friendly native plants, power their buildings with fully renewable resources and give some excess back to the grid, or support every employee’s growth and potential.

Like the Sustainability stage, on-the-ground implementation of the Flourishing stage is in a nascent state, operationalized at a few small, local businesses, farms, and residences, and partially implemented by some large businesses. Widespread implementation has a long way to go, and yet the vision is compelling, necessary, and gaining traction.

Back in 1977, when I plunged into the effluent outfall in Abrams Creek, my hometown sewage plant was a significant polluter—we would place it squarely in the Conquest stage, oblivious to environmental and social concerns. Today, a new facility provides state-of-the-art wastewater treatment and seeks to be an innovative leader in green energy production, processing municipal sludge and organic waste into methane gas. These new ways of doing business demonstrate the Sustainability Continuum in action and provide glimmers of the Flourishing stage that is possible. The great challenge of businesses today— and really the challenge confronting all of us—is not only to comply with natural and human limits, but to consciously improve the systems in which we live and work.

Cary Gaunt has spent most of her career leading watershed restoration efforts around the country for Science Applications International Corporation, and was lucky to spend much of her time working on her home watershed, the Chesapeake Bay. She is now a faculty member in Marlboro’s MBA in Managing for Sustainability program, where she teaches Exploring Sustainability and conducts research on ecologically enlightened leadership and ways businesses can enter the Flourishing stage of the Sustainability Continuum.

Business Doing Good

When John Tedesco MBA ’12 was working on his Capstone Project, he was the safety and environmental manager at Green Mountain Power (GMP), where he has worked for nearly 10 years. “I was deeply involved in GMP’s corporate social responsibility reporting (CSR), and I wanted to take our commitment further.” He chose to focus on how GMP could meet the rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency spelled out by the nonprofit B Lab. It was therefore gratifying for John when, in December, Green Mountain Power was recognized as the first utility company in the world to become a Certified B Corp. “Regulated monopolies tend to move at a glacial pace when it comes to innovation and forward thinking,” says John. “GMP has shown that you can thrive within the regulated sector and lead the way. Basically it shows the world that all businesses can do good.”

When John Tedesco MBA ’12 was working on his Capstone Project, he was the safety and environmental manager at Green Mountain Power (GMP), where he has worked for nearly 10 years. “I was deeply involved in GMP’s corporate social responsibility reporting (CSR), and I wanted to take our commitment further.” He chose to focus on how GMP could meet the rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency spelled out by the nonprofit B Lab. It was therefore gratifying for John when, in December, Green Mountain Power was recognized as the first utility company in the world to become a Certified B Corp. “Regulated monopolies tend to move at a glacial pace when it comes to innovation and forward thinking,” says John. “GMP has shown that you can thrive within the regulated sector and lead the way. Basically it shows the world that all businesses can do good.”