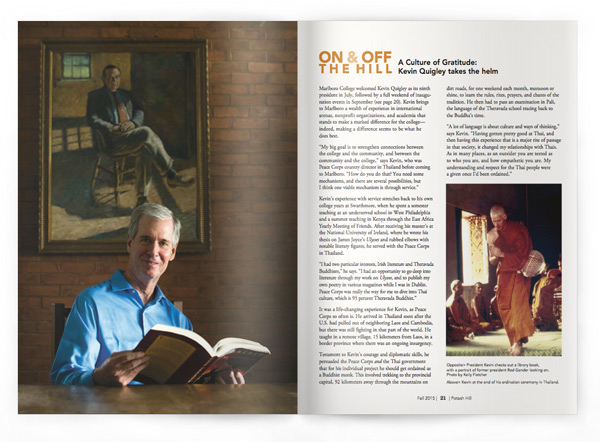

A Culture of Gratitude: Kevin Quigley takes the helm

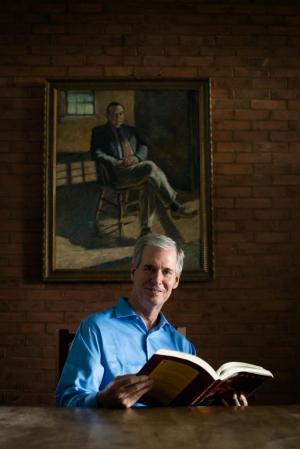

Marlboro College welcomed Kevin Quigley as its ninth president in July, followed by a full weekend of inauguration events in September (see page 20). Kevin brings to Marlboro a wealth of experience in international arenas, nonprofit organizations, and academia that stands to make a marked difference for the college—indeed, making a difference seems to be what he does best.

“My big goal is to strengthen connections between the college and the community, and between the community and the college,” says Kevin, who was Peace Corps country director in Thailand before coming to Marlboro. “How do you do that? You need some mechanisms, and there are several possibilities, but I think one viable mechanism is through service.”

Kevin’s experience with service stretches back to his own college years at Swarthmore, when he spent a semester teaching at an underserved school in West Philadelphia and a summer teaching in Kenya through the East Africa Yearly Meeting of Friends. After receiving his master’s at the National University of Ireland, where he wrote his thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses and rubbed elbows with notable literary figures, he served with the Peace Corps in Thailand.

“I had two particular interests, Irish literature and Theravada Buddhism,” he says. “I had an opportunity to go deep into literature through my work on Ulysses, and to publish my own poetry in various magazines while I was in Dublin. Peace Corps was really the way for me to dive into Thai culture, which is 95 percent Theravada Buddhist.”

It was a life-changing experience for Kevin, as Peace Corps so often is. He arrived in Thailand soon after the U.S. had pulled out of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but there was still fighting in that part of the world. He taught in a remote village, 15 kilometers from Laos, in a border province where there was an ongoing insurgency.

Testament to Kevin’s courage and diplomatic skills, he persuaded the Peace Corps and the Thai government that for his individual project he should get ordained as a Buddhist monk. This involved trekking to the provincial capital, 92 kilometers away through the mountains on dirt roads, for one weekend each month, monsoon or shine, to learn the rules, rites, prayers, and chants of the tradition. He then had to pass an examination in Pali, the language of the Theravada school tracing back to the Buddha’s time.

“A lot of language is about culture and ways of thinking,” says Kevin. “Having gotten pretty good at Thai, and then having this experience that is a major rite of passage in that society, it changed my relationships with Thais. As in many places, as an outsider you are tested as to who you are, and how empathetic you are. My understanding and respect for the Thai people were a given once I’d been ordained.”

Kevin’s service in Thailand altered how he thought of himself relative to the rest of humanity: he developed an abiding sense of compassion and, as they say in the Peace Corps, became at home in the world. It also gave him important skills he would use throughout his career and, perhaps most importantly, steeled his resolve to learn what was needed to make a difference.

“I saw what a raw deal my students and their parents got, and how they didn’t have access to resources. To someone who had done nothing but the humanities in college, it was an eye-opening experience—but like students here at Marlboro, I had also learned how to learn, and my time in Thailand motivated me to learn about economics and politics. I wanted to make things a little better for people like the villagers I worked with.”

Kevin had an internship with the United Nations Development Program in Trinidad and Tobago, and earned his Master of International Affairs in economic and political development from Columbia University. Then, in Washington D.C., he oversaw foreign assistance agencies in President Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget and served as legislative director to U.S. Senator John Heinz, focusing on international financial and education issues. It was “a fabulous education inhow Washington and the world worked,” says Kevin, but the real watershed moment came in 1989, when he started as director of public policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“It’s really rare in life that you can think of a problem or issue, and your first concern doesn’t have to be about resources,” says Kevin. “Although I hadn’t even heard of it before, at that time Pew was the second-largest foundation in the U.S., based on money out the door.” It was the end of the Soviet Union, the establishment of newly independent nations and economies in Central Europe, and all of the new leaders wanted access to Western ideas and resources. “Pew commanded the resources, so I got to meet many of the individuals, like Lech Walesa, Vaclav Havel, and others, who had a major impact on that democratization process.”

Following on his work in the former Soviet republics, Kevin published his book For Democracy’s Sake: Foundations and Democracy Assistance in Central Europe (Johns Hopkins University Press), in 1997. He was interested in how political and economic changes were effected, and what role outsiders have in encouraging or promoting such changes. Unlike after World War II, when the U.S. government helped rebuild Germany and Japan, there was no such appetite for public investment after the fall of the Berlin Wall. For better or worse, private foundations were the principal catalyst for change.

“I thought, this may be a completely unique experience in recent human history, a really interesting shift in what drives global change. I wanted to provide an opportunity for people at the forefront, leaders who were all so courageous, to assess what worked and what didn’t.” Kevin helped his colleagues in Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland organize case studies in each country, providing financial and technical support, translating the results into their national language, and discussing them in public forums.

During his time at Pew, Kevin completed his doctoral degree in comparative government at Georgetown University. He wanted to conduct his own research on social change, but rather than focusing on Central Europe—where there might be conflicts of interest with his foundation work—he went back to Thailand. There he knew the language and culture, and was very familiar with the national challenges of democratization.

“I was particularly interested in the role that civil society organizations play in creating democratic culture. Because unless you have the values of democracy, you can create the best independent parliament, the freest press, and it’s not going to mean anything. You need a culture that respects minority rights; encourages tolerance, empathy, and patience; has accountability and transparency. So how do you create that? There are really three mechanisms: governmental, market, and civil society, that vital space between markets and the public sector.”

Kevin went on to serve as vice president for business and policy at the Asia Society and Museum, in New York, and the first executive director for the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities, based in Baltimore, Maryland. In the latter role, he pioneered work withglobal companies like Nike and The Gap, the World Bank, and various universities and community-based organizations, seeking to improve the lives of production workers. He also launched his own consulting firm, called Q&A: Quigley & Associates, working for values-based organizations on strategy, program development, and resource mobilization issues.

In 2003 Kevin came full circle, so to speak, and began nearly 10 years of service as president and CEO of the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), the global alumni organization for 200,000 former volunteers and staff. There he developed a community-based model for the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary, using social media to spark the largest engagement ever, and established the More Peace Corps Campaign, resulting in the highest appropriation in the agency’s history—a $60 million increase. He also helped secure passage of the Peace Corps Commemorative Act, signed into law by President Obama.

During his time at NPCA, Kevin designed and secured endowment funding for the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award, which recognizes volunteers’ impact on individuals they serve. The award is named for one ofKevin’s mentors, Harris Wofford, the former senator, advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., and aide to President Kennedy, who was instrumental in the formation of the Peace Corps.

“Harris is kind of the godfather of service, in our country,” says Kevin, who has found inspiration in both Wofford and Sargent Shriver, statesman, activist, and the driving force behind the founding of the Peace Corps. “Both of them were always about the future. They were pragmatic idealists: they thought big, but could deliver, could make things happen to improve the lives of people.”

Throughout his career, Kevin has maintained a deep appreciation for and engagement with academia. He was a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow at 12 liberal arts colleges from 2004 to 2012, and a faculty-practitioner graduate instructor teaching about international studies and nonprofit management from 1995 to 2011. Earlier, he was guest scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the recipient of several other international professional fellowships. He has served on the board of Swarthmore College and the American University of Afghanistan.

“Liberal arts education, especially in distinctive and academically rich settings such as Marlboro College, has a unique ability to anticipate change and prepare individuals for thoughtful, purposeful, and effective engagement in the world,” says Kevin. “What can you do with a liberal arts education? As my life suggests: anything and everything—it prepares you for a life unexpected.”

“For example, I’ve never had a course in economics and politics, and most of my life has been spent in those arenas. At its best, a liberal arts education stirs a passion for lifelong learning, looking at new opportunities as they come along, and making a difference. That’s what excites me, and that’s why I’m eager to make a contribution here at Marlboro.”

Kevin recognizes that Marlboro College is in a competitive environment, that small, independent, liberal arts colleges are under siege, and that many of them offer self-directed learning in small, interdisciplinary settings. But in his short time here so far he finds that what is most distinctive about Marlboro is the profound sense of community.

“Community has always been part of the ethos, and it’s reflected in the shared governance model. When people talk about shared governance in the liberal arts context, they’re talking about staff, faculty, and board—they’re not including students. While many liberal arts colleges share the objective of helping students become citizens of the world—and I’m a believer in experiential learning— I think Marlboro has a leg up because of our practices as a community.”

Kevin is looking forward to encouraging a more robust student life, including more activities on evenings and weekends and more interactions with local and global communities, as well as with the graduate campus in Brattleboro. “I see it in our culture, I see it in our heritage, but we have to have the programs that reflect the importance of community at Marlboro,” he says.

“I think of community as having shared values and experiences and aspirations. As community members we get opportunities and privileges, but we also have some responsibilities to other people. How do I express my gratitude at being a member of community? How do I fulfill part of my obligations? Service is a great way to do it, and it’s particularly powerful in an educational context, because service helps us learn life lessons and is the gift that keeps on giving.”

Celebrating President Kevin

Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

Students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, and friends from near and far gathered on September 13, 2015, for the inauguration of Dr. Kevin Quigley as Marlboro College’s ninth president. A drizzly day could not dampen spirits as the college community reveled in the celebration of Marlboro and its promising future under the guidance of President Kevin.

“Although change is never easy, Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher, teaches us that change is an entirely natural process since ‘no one steps into the same river twice,’” said Kevin in his inaugural address, titled “Marlboro Matters: The Engaged Marlboro Community of the Future.”

“The Marlboro of today is different from the Marlboro of yesterday and will be from the one of tomorrow. That river flows on, and we all must necessarily evolve with the flow. Our very engaged and amazingly supportive board has responded creatively and quickly to current challenges— again supporting how much Marlboro matters.

“Over the past few months, I have come to more deeply appreciate the fact that Marlboro matters because it continues to teach invaluable, timeless skills that have broad applicability: to think critically, to read closely, to communicate compellingly, to work in community.

“Liberal arts, as the Greeks first posited, and as it is more recently argued by public intellectuals like Fareed Zakaria, is the best preparation for an engaged life and citizenship. As my life suggests, liberal arts graduates can do anything and everything, everywhere. There is also growing evidence from leading corporations, that they want liberal arts graduates because they work well across disciplines, problem solve, and communicate in ways that some other graduates can’t.”

For more excerpts, photos, and video from the ceremony, go to marlboro.edu/inauguration.