Seeking Common Ground in Patagonia

By Matt McIntosh ’17

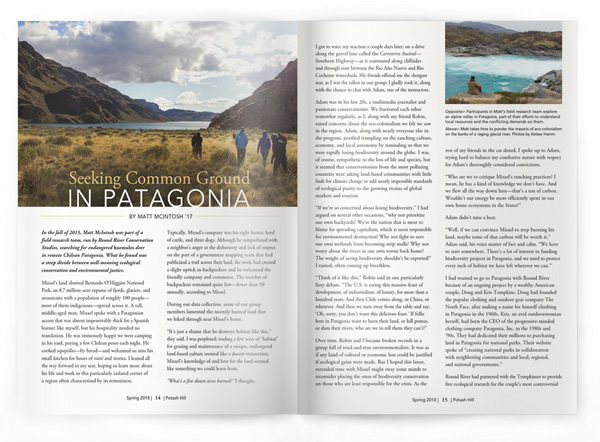

In the fall of 2015, Matt McIntosh was part of a field research team, run by Round River Conservation Studies, searching for endangered huemules deer in remote Chilean Patagonia. What he found was a steep divide between well-meaning ecological conservation and environmental justice.

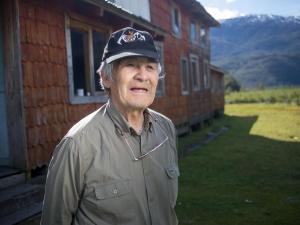

Misael’s land abutted Bernardo O’Higgins National Park, an 8.7 million–acre expanse of fjords, glaciers, and mountains with a population of roughly 100 people—most of them indigenous—spread across it. A tall, middle-aged man, Misael spoke with a Patagonian accent that was almost impenetrably thick for a Spanish learner like myself, but his hospitality needed no translation. He was immensely happy we were camping in his yard, paying a few Chilean pesos each night. He cooked sopapillas—fry bread—and welcomed us into his small kitchen for hours of maté and stories. I leaned all the way forward in my seat, hoping to learn more about his life and work in this particularly isolated corner of a region often characterized by its remoteness.

Typically, Misael’s company was his eight horses, herd of cattle, and three dogs. Although he sympathized with a neighbor’s anger at the dishonesty and lack of respect on the part of a government mapping team that had publicized a trail across their land, the work had created a slight uptick in backpackers and he welcomed the friendly company and commerce. The number of backpackers remained quite low—fewer than 50 annually, according to Misael.

During our data collection, some of our group members lamented the recently burned land that we hiked through near Misael’s home.

“It’s just a shame that he destroys habitat like this,” they said. I was perplexed; trading a few acres of “habitat” for grazing and maintenance of a unique, endangered land-based culture seemed like a decent transaction. Misael’s knowledge of and love for the land seemed like something we could learn from.

I got to voice my reaction a couple days later, on a drive along the gravel lane called the Carreterra Austral—Southern Highway—as it contoured along cliffsides and through mist between the Rio Año Nuevo and Rio Cochrane watersheds. My friends offered me the shotgun seat, as I was the tallest in our group; I gladly took it, along with the chance to chat with Adam, one of the instructors.

Adam was in his late 20s, a multimedia journalist and passionate conservationist. We frustrated each other somewhat regularly, as I, along with my friend Robin, raised concerns about the eco-colonialism we felt we saw in the region. Adam, along with nearly everyone else in the program, justified trampling on the ranching culture, economy, and local autonomy by reminding us that we were rapidly losing biodiversity around the globe. I was, of course, sympathetic to the loss of life and species, but it seemed that conservationists from the most polluting countries were asking land-based communities with little fault for climate change to add nearly impossible standards of ecological purity to the growing strains of global markets and tourism.

“If we’re so concerned about losing biodiversity,” I had argued on several other occasions, “why not prioritize our own backyards? We’re the nation that is most to blame for spreading capitalism, which is most responsible for environmental destruction! Why not fight to save our own wetlands from becoming strip malls? Why not worry about the rivers in our own towns back home? The weight of saving biodiversity shouldn’t be exported!” I ranted, often coming up breathless.

“Think of it like this,” Robin said in one particularly fiery debate. “The U.S. is eating this massive feast of development, of industrialism, of luxury, for more than a hundred years. And then Chile comes along, or China, or wherever. And then we turn away from the table and say, ‘Oh, sorry, you don’t want this delicious feast.’ If folks here in Patagonia want to burn their land, or kill pumas, or dam their rivers, who are we to tell them they can’t?”

Over time, Robin and I became broken records in a group full of tried-and-true environmentalists. It was as if any kind of cultural or economic loss could be justified if ecological gains were made. But I hoped this latest, extended time with Misael might sway some minds to reconsider placing the onus of biodiversity conservation on those who are least responsible for the crisis. As the rest of my friends in the car dozed, I spoke up to Adam, trying hard to balance my combative nature with respect for Adam’s thoroughly considered convictions.

“Who are we to critique Misael’s ranching practices? I mean, he has a kind of knowledge we don’t have. And we flew all the way down here—that’s a ton of carbon. Wouldn’t our energy be more efficiently spent in our own home ecosystems in the States?”

Adam didn’t miss a beat.

“Well, if we can convince Misael to stop burning his land, maybe some of that carbon will be worth it,” Adam said, his voice matter of fact and calm. “We have to start somewhere. There’s a lot of interest in funding biodiversity projects in Patagonia, and we need to protect every inch of habitat we have left wherever we can.”

I had wanted to go to Patagonia with Round River because of an ongoing project by a wealthy American couple, Doug and Kris Tompkins. Doug had founded the popular clothing and outdoor gear company The North Face, after making a name for himself climbing in Patagonia in the 1960s. Kris, an avid outdoorswoman herself, had been the CEO of the progressive-minded clothing company Patagonia, Inc. in the 1980s and ’90s. They had dedicated their millions to purchasing land in Patagonia for national parks. Their website spoke of “creating national parks in collaboration with neighboring communities and local, regional, and national governments.”

Round River had partnered with the Tompkinses to provide free ecological research for the couple’s most controversial project yet, “The Future Patagonia National Park.” Their website touted their goal of “fostering local economic progress as a consequence of conservation.” The Tompkinses had every intention of handing over these 174,000 acres to the Chilean public when they had finished various infrastructure projects. But, despite talk of “national parks as a cornerstone of democracy,” many locals felt there was nothing democratic about the way the Tompkinses had purchased a once productive estancia (ranch) that had anchored the commerce of a small town called Cochrane before globalization crippled small-scale ranching and turned it into a tourist destination for the wealthy. The cheapest rooms in the hotel—“El Lodge”—cost $350.

On a steep slope a thousand feet above the Rio Baker, a muscular young gaucho named Wilson pointed out which plants could be trusted to hold my weight in case of a fall. As we traversed the ridge in search of endangered huemules, a deer featured on Chile’s crest, I watched Wilson leap six feet across a 20-foot drop into a rocky creek. He turned, pointing to the branches he had grabbed to secure his landing.

“This,” he said, shaking a ñirre branch. “Not this,” he said, pointing to a less substantial bush downhill.

Trying to appear nonchalant, I nodded. A fall into the chasm below would be, in the best case scenario, a trip-ender. I took a few steps back and launched myself toward the opposite side. My boots squelched loudly into the muddy bank, and I began slipping backward.

“La rama!” Wilson said, beginning to reach toward me. “The branch!”

I gripped the ñirre’s rough bark and pulled myself back onto solid ground. I started laughing.

“Muy cerca, no?” I chuckled. “Very close!”

“Yes, yes,” Wilson smiled, looking relieved. “Hay solamente una regla hoy. No sangre de gringo,” he said, laughing.

“There is only one rule today. No gringo blood.”

I laughed, embarrassed, and we continued our traverse. It had been fruitless thus far. The huemules were not doing well in this area near Cochrane. Locals blamed the gatos de Tompkins for the demise of their national symbol. The Tompkinses had been fostering habitat for pumas on their substantial acreage, in addition to putting tracking collars on the apex predators to monitor their activity and health. The former employees of the estancia behaved as most gauchos did toward pumas: shoot first, ask questions later. Pumas were notorious for killing livestock.

“For every puma that you see, one hundred have seen you,” Wilson told me in careful English as we stood above a barely decipherable paw print. “It is fresh,” Wilson said. I smiled and glanced around, a little nervous.

Many locals were unequivocally opposed to the outside influence the Tompkinses wielded in their community. Their status as Americans made their chances of ameliorating the situation even worse. Augusto Pinochet’s bloody dictatorship began in 1973 after the CIA helped “foster” a coup in response to the democratically-elected socialist president Salvador Allende’s leftist policies. This resulted in significant anti-American sentiment in Chile, all the way down to minuscule Cochrane.

One day, when we were camping in the sheep pasture of a gaucho named Gilberto, he invited Robin and me down by the Rio Cochrane to watch the slaughter of a lamb. The lamb would be roasted on a stake in front of a fire for the traditional Patagonian meal known as an asado. It was a beautiful Saturday in December. Patagonia’s spring was full of bright green ñirre leaves, chirping birds, and warm sunshine. Never having killed anything larger than a fish, I was excited and a bit nervous to witness the act. When Gilberto saw me turn my eyes from the lamb’s suffering, he assumed I could not handle the sight.

“These gringos,” he said with a derisive smile. “They cause more bloodshed than anyone else in the world, but they cannot watch a lamb die.”

We all chuckled. I had no interest in defending myself. His point spoke volumes about the immense gap between the views of some locals and those of Round River and the Tompkinses. Robin and I had tried to separate ourselves in Gilberto’s eyes by volunteering to help him with tasks on the campo. But we’d always be gringos, complicit and ripe for the teasing.

The Tompkinses viewed biodiversity as worthy of defense at all costs, including local cultures that do not pass their rigorous ecological standards. Patagonians defended their way of life fiercely and measured the land’s health in conjunction with its ability to support them. Their culture and regional pride, as well as a wealth of local knowledge and land-based traditions, were rooted in the land’s bounty and beauty.

Despite these differences, I wondered if a mutual love of the land could foster some kind of harmony between these conflicting ideologies. Cochrane (and Patagonia in general) needs to prepare for the onslaught of tourism, which all parties agreed was imminent. Who would profit from this? And who would control the narrative that tourists hear? The answer to these questions will have significant implications on how the land will be used in the future, and if the gaucho culture’s wisdom will survive. This wisdom, I thought, could be used to protect both land and culture in future fights for the region.

Despite these differences, I wondered if a mutual love of the land could foster some kind of harmony between these conflicting ideologies. Cochrane (and Patagonia in general) needs to prepare for the onslaught of tourism, which all parties agreed was imminent. Who would profit from this? And who would control the narrative that tourists hear? The answer to these questions will have significant implications on how the land will be used in the future, and if the gaucho culture’s wisdom will survive. This wisdom, I thought, could be used to protect both land and culture in future fights for the region.

I could only conclude that the wounds of the past—those directly and indirectly caused by the Tompkinses—appeared to leave any common ground infertile. The day before I departed Cochrane to return home, Doug Tompkins died in a kayaking accident on Lago General Carrera, a few hours north of Cochrane. Gilberto had given me the news as we ate together in the quincho, or common area. His tone was calm, matter of fact, and dignified. There was no sadness.

“I will keep his family in my prayers,” he said, before walking out to tend to the sheep.

Matthew McIntosh graduated in 2017 with a Plan of Concentration in environmental studies and politics, including essays exploring place, history, and community in Memphis, northern Minnesota, and northern New Mexico. He is now working as a guide for Outward Bound California and organizing within the guiding community to protect endangered cultures, species, and ecosystems.