The Eternal Presence of Absence

By Lauren Beigel MacArthur ‘02

While politicians debate draconian immigration laws and border officials carry them out, activists and nonprofit organizations are left to measure the cost in human lives and suffering. More than a decade after working for refugee rights in Arizona, Lauren Beigel MacArthur returned there to witness the activism of anthropologist-turned-artist Alvaro Enciso.

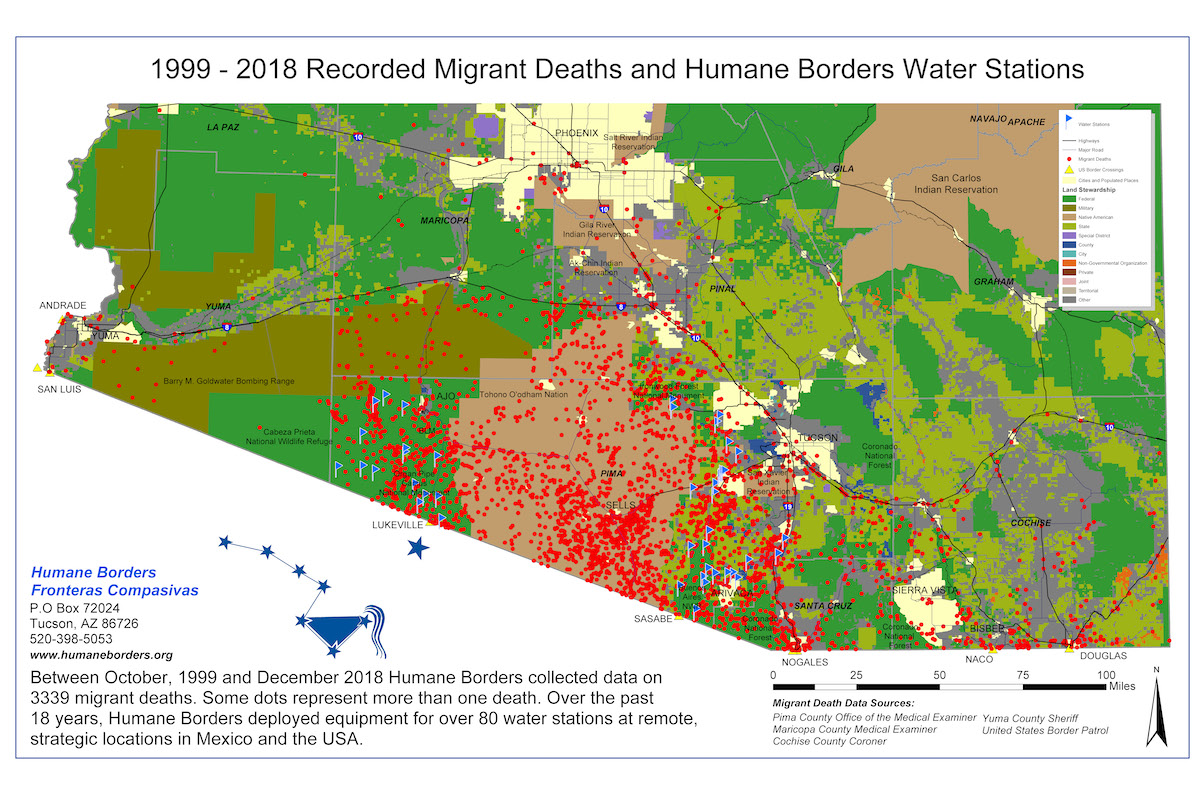

Many who wish to come to the United States do not make it. Since 2001, there have been at least 3,000 migrant deaths in the Arizona desert alone. Colombian-born activist Alvaro Enciso honors these people and their shattered dreams through his art. He paints in vibrant colors, using mixed media and incorporating items left behind by migrant border-crossers, such as metal from food cans and shoe leather. His work echoes the concepts of lost chances, life between worlds: the essence of the harsh borderlands. Last March, I was fortunate to join Alvaro on a trip to the border to mourn and honor those whose lives ended before their story here could begin.

I first moved to Arizona in 2003 to work at the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. I was a year out of Marlboro College and looking for travel, challenge, and meaning in my work. There, I worked with a team of lawyers to assist detained immigrants and refugees in deportation proceedings, giving “know your rights” presentations and helping individuals who had cases to remain in this country. I talked with over 50 detainees a day, and these were the ones who had made it here, made homes here, and were now being spat out by the unforgiving machine of US immigration law.

In my work I heard many, many stories about border crossings—walks through deserts, dangerous drives, weeks in shipping containers, losing family members, money, and possessions along the way. After two years, my heart and soul were battered, exhausted, and longing to return to Vermont. I did come home to these Green Mountains, but lodged in my heart was that state, that border, and that crisis—those individual lives so devastated by our country’s inhumane immigration policies. After more than a decade, I have begun to revisit Arizona, and this spring I was able to return to the border with Alvaro.

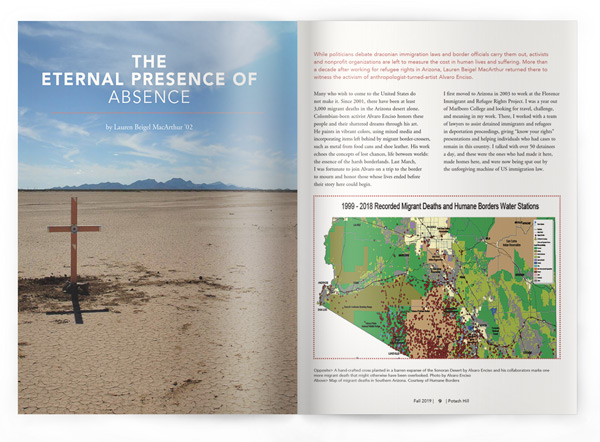

lvaro has created his own “red dot” project, entitled Donde Mueren los Sueños (where dreams die), in which he places hand-crafted wooden crosses on the exact sites of migrant deaths. Using information provided by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, he hikes out into the desert with small groups of helpers to find the “red dots” on the map and pay tribute. This project has recently gained national recognition as the border has become a kind of war zone and political focal point.

Donde Mueren los Sueños began as an effort to honor the deceased migrants, and has turned into an action that is drawing new awareness to what has been happening on the border for quite some time. Recent border walls and immigration policies have pushed desperate border crossers into harsher and more dangerous territory, where there is little water and temperatures are well above 100 degrees for many months of the year. Alvaro has placed over 900 crosses, and shows no signs of slowing down.

“No one in Vermont was thinking about the border, and the people who are dying here,” said Alvaro. “No one in Ohio was thinking about it either. But then suddenly the newspaper is mentioning this crazy old guy putting crosses up in the desert, and it catches their attention, and then I hope they’ll begin to think about it.”

While visiting Arizona in March with my family, I had the opportunity to join Alvaro on one of his weekly trips to the border. With Alvaro at the wheel of a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle, I sat wedged between two members of the Tucson Samaritans group, locals who care deeply about the plight of migrant border-crossers. These activists spend their weekends hiking remote canyons and leaving gallons of water and other supplies for migrants who might come that way, something for which they now risk criminal charges.

As we drove south from Tucson toward the small border town of Arivaca, the Samaritans told me about their weekly meetings with a large group of concerned Tucsonians, and how they volunteer at shelters for asylum seekers. They talked about joining protests and civil disobedience actions in places like Arivaca, a town suddenly overrun with US Border Patrols, “militias,” and the harsh reality that current immigration policies have written a death sentence for so many desperate people. Now funneled through this desert corridor and channeled through drug traffickers’ mafia-like hierarchy, migrants face an incredibly perilous journey if they decide to travel overland from Mexico to the United States.

We picked up our navigator in Arivaca, a sturdy young woman who clutched the GPS to her chest and led us to the exact point where skeletal remains had been found in the early 2000s. We drove out rough dirt roads winding through grassy knolls dotted with mesquite, rising in and out of dry, rocky washes. Our navigator pointed out a place she’d tried to camp recently with some friends.

“The Border Patrol kept driving by, slowing down to look at us every time they went by,” she said. “We finally got sick of it and just packed up our campsite and left.” I realized that she could be mistaken for a Mexican, with her dark hair and indigenous-looking cheekbones.

We parked at a cattle corral and walked over a ridge into rustling grass, with an eye out for rattlesnakes. The powerful Arizona sun pressed down upon our backs, and our small group stopped to wipe off sweat, drink from our full water bottles, and have a snack before continuing on. We were eight miles from the border when we reached the site of the red dot, in lovely, rolling hills with views of distant mountains. We set to work digging a hole, placing the salmon-colored cross, pouring in some quick-dry concrete and water, and placing rocks around the base of the cross. We stood for a while in silence. There was no information about this deceased person. No name or cause of death.

I imagined what it would be like to die here. Did this person know that just over the ridge was a dirt road that could be followed to the highway? Were they alone here? Did their family ever find out what happened to them? Alvaro spoke of the “eternal presence of absence”: how this person still occupies an empty chair at the holidays, still represents a question mark in his or her family’s mind. Their family is probably still wondering if someday the phone will ring or they will hear footsteps at their door. “Each of these deaths is a tragedy, and ripples out into others’ lives,” Alvaro said.

We left the lonely cross and three gallons of water (“hidden” in some shrubs), and set off in our vehicle down a rough rancher’s track into the hills. There was a border patrol tower perched on top of one of the higher knolls, and I thought of how unsettling it would be to walk through these hills, knowing that so many eyes could be watching. We could see on the GPS map that another site Alvaro had already marked was not far off this rough road, and finally parked by a small stream. We followed our navigator up a steep slope to the backside of a small tree, a branch looming above us.

A young man named Isidro Revollar-Herrera had died here, taking his own life. It was painful to imagine what he must have been experiencing to drive him to this fate. Alvaro explained the kind of pain that a slow death by heat and dehydration could inflict, and how seeking relief in hanging oneself with a belt or shirt was not a quick escape either. From Isidro’s last view, we could see the dirt track winding out of sight.

I hope to continue to return to the desert to hike the canyons and enjoy its surreal beauty, but my privilege to do so is never far from my mind. I think of the ridiculous “reality” television shows that glorify “survivors” or those who struggle through obstacle courses to get to an arbitrary finish line. In actual reality, the migrant men, women, and children who navigate the most dangerous route imaginable into our country deserve just as much recognition: for the physical feat and the emotional steeliness they need to embody. They deserve to collapse at the finish line into our arms, to be fed, housed, clothed, and awarded compassion. But even if they make it here, their race has only begun. And if they do not, a humble artist will mark the story of their lives with a painted wooden cross.

Lauren Beigel MacArthur completed her Plan in environmental studies, with a focus on tropical agroecology and Latin American literature, in 2002. She received an MEd at Antioch New England and taught middle school humanities for five years before having two children and running Whetstone CiderWorks with her husband. She currently lives a patchwork Vermont life in Marlboro as a farmer, child advocate, cook, and creative writing teacher, among many other things. For further reading she recommends The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, by Francisco Cantú, and The Devil’s Highway, by Luis Alberto Urrea. For more information about Alvaro Enciso and his work, visit facebook.com/alvaro.enciso.5.

Legislating Refugees

“Trade laws and work programs passed by the United States in nearby Puerto Rico and Mexico have weakened the economies of these already struggling countries for many years,” says Emmett Wood ’19. In a Plan titled “A multidimensional study of the Latino-American narrative,” Emmett explores the history of laws like the Treaty of Paris, the Jones Act, Operation Bootstrap, and the Bracero Program, combined with interviews with Puerto Rican Americans about their experiences. “My research seeks to explore the US’s largely self-inflicted Latino immigration ‘problem,’ and simultaneously allows space for the voices of modern-day Puerto Rican Americans struggling with many of the same issues as those who came before them,” says Emmett. “I pose the question: How does legislation passed between 50 and 100 years ago still affect the lives of Latino Americans today?”

“Trade laws and work programs passed by the United States in nearby Puerto Rico and Mexico have weakened the economies of these already struggling countries for many years,” says Emmett Wood ’19. In a Plan titled “A multidimensional study of the Latino-American narrative,” Emmett explores the history of laws like the Treaty of Paris, the Jones Act, Operation Bootstrap, and the Bracero Program, combined with interviews with Puerto Rican Americans about their experiences. “My research seeks to explore the US’s largely self-inflicted Latino immigration ‘problem,’ and simultaneously allows space for the voices of modern-day Puerto Rican Americans struggling with many of the same issues as those who came before them,” says Emmett. “I pose the question: How does legislation passed between 50 and 100 years ago still affect the lives of Latino Americans today?”