Hauntings on the Hill

by Aaron Damon-Rush ’22

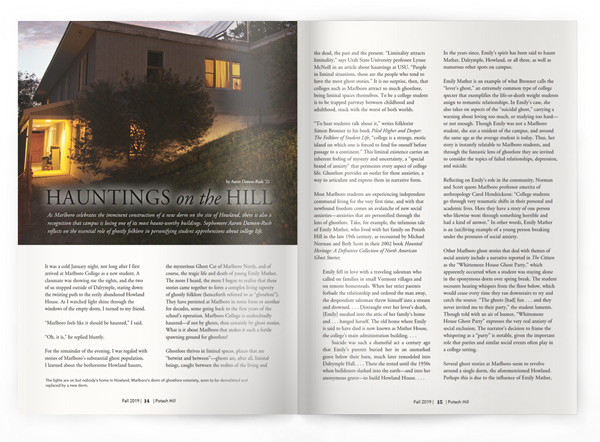

As Marlboro celebrates the imminent construction of a new dorm on the site of Howland, there is also a recognition that campus is losing one of its most haunt-worthy buildings. Sophomore Aaron Damon-Rush reflects on the essential role of ghostly folklore in personifying student apprehensions about college life.

It was a cold January night, not long after I first arrived at Marlboro College as a new student. A classmate was showing me the sights, and the two of us stopped outside of Dalrymple, staring down the twisting path to the eerily abandoned Howland House. As I watched light shine through the windows of the empty dorm, I turned to my friend.

“Marlboro feels like it should be haunted,” I said.

“Oh, it is,” he replied bluntly.

For the remainder of the evening, I was regaled with stories of Marlboro’s substantial ghost population. I learned about the bothersome Howland haunts, the mysterious Ghost Cat of Marlboro North, and of course, the tragic life and death of young Emily Mather. The more I heard, the more I began to realize that these stories came together to form a complex living tapestry of ghostly folklore (henceforth referred to as “ghostlore”). They have persisted at Marlboro in some form or another for decades, some going back to the first years of the school’s operation. Marlboro College is undoubtedly haunted—if not by ghosts, then certainly by ghost stories. What is it about Marlboro that makes it such a fertile spawning ground for ghostlore?

Ghostlore thrives in liminal spaces, places that are “betwixt and between”—ghosts are, after all, liminal beings, caught between the realms of the living and the dead, the past and the present. “Liminality attracts liminality,” says Utah State University professor Lynne McNeill in an article about hauntings at USU. “People in liminal situations, those are the people who tend to have the most ghost stories.” It is no surprise, then, that colleges such as Marlboro attract so much ghostlore, being liminal spaces themselves. To be a college student is to be trapped partway between childhood and adulthood, stuck with the worst of both worlds.

“To hear students talk about it,” writes folklorist Simon Bronner in his book Piled Higher and Deeper: The Folklore of Student Life, “college is a strange, exotic island on which one is forced to fend for oneself before passage to a continent.” This liminal existence carries an inherent feeling of mystery and uncertainty, a “special brand of anxiety” that permeates every aspect of college life. Ghostlore provides an outlet for these anxieties, a way to articulate and express them in narrative form.

Most Marlboro students are experiencing independent communal living for the very first time, and with that newfound freedom comes an avalanche of new social anxieties—anxieties that are personified through the lens of ghostlore. Take, for example, the infamous tale of Emily Mather, who lived with her family on Potash Hill in the late 19th century, as recounted by Michael Norman and Beth Scott in their 2002 book Haunted Heritage: A Definitive Collection of North American Ghost Stories:

Emily fell in love with a traveling salesman who called on families in small Vermont villages and on remote homesteads. When her strict parents forbade the relationship and ordered the man away, the despondent salesman threw himself into a stream and drowned. . . . Distraught over her lover’s death, [Emily] sneaked into the attic of her family’s home and . . . hanged herself. The old home where Emily is said to have died is now known as Mather House, the college’s main administration building. . . . Suicide was such a shameful act a century ago that Emily’s parents buried her in an unmarked grave below their barn, much later remodeled into Dalrymple Hall. . . . There she rested until the 1950s when bulldozers slashed into the earth—and into her anonymous grave—to build Howland House. . . .

In the years since, Emily’s spirit has been said to haunt Mather, Dalrymple, Howland, or all three, as well as numerous other spots on campus.

Emily Mather is an example of what Bronner calls the “lover’s ghost,” an extremely common type of college specter that exemplifies the life-or-death weight students assign to romantic relationships. In Emily’s case, she also takes on aspects of the “suicidal ghost,” carrying a warning about loving too much, or studying too hard— or not enough. Though Emily was not a Marlboro student, she was a resident of the campus, and around the same age as the average student is today. Thus, her story is instantly relatable to Marlboro students, and through the fantastic lens of ghostlore they are invited to consider the topics of failed relationships, depression, and suicide.

Reflecting on Emily’s role in the community, Norman and Scott quote Marlboro professor emerita of anthropology Carol Hendrickson: “College students go through very traumatic shifts in their personal and academic lives. Here they have a story of one person who likewise went through something horrible and had a kind of answer.” In other words, Emily Mather is an (un)living example of a young person breaking under the pressures of social anxiety.

Other Marlboro ghost stories that deal with themes of social anxiety include a narrative reported in The Citizen as the “Whittemore House Ghost Party,” which apparently occurred when a student was staying alone in the eponymous dorm over spring break. The student recounts hearing whispers from the floor below, which would cease every time they ran downstairs to try and catch the source. “The ghosts [had] fun . . . and they never invited me to their party,” the student laments. Though told with an air of humor, “Whittemore House Ghost Party” expresses the very real anxiety of social exclusion. The narrator’s decision to frame the whispering as a “party” is notable, given the important role that parties and similar social events often play in a college setting.

Several ghost stories at Marlboro seem to revolve around a single dorm, the aforementioned Howland. Perhaps this is due to the influence of Emily Mather, as Howland is one of the buildings she is frequently said to haunt. Several students say that their time in Howland was marked by strange noises and disturbances in the night. In the words of one anonymous student cited in The Citizen:

I thought that my neighbors were just noisy. It sounded like they were dropping bowling balls and rolling marbles across the floor. When I would confront them they’d swear they didn’t know what I was talking about. Sometimes when the noise would get bad, I would go upstairs only to discover that no one was in the room above me, or worse yet, that the noises were absolutely not coming from upstairs, but rather, within my own walls.

In narratives such as these, the college student’s anxiety about noisy or otherwise disruptive neighbors is given a supernatural twist. Other stories recounted in The Citizen tell of uneasy sleep within Howland’s rooms. One Marlboro student described waking at 3:00 am “on the dot” every single morning, going outside, and walking the same path. Another said they woke up from a deep sleep with a feeling that “the other person in bed was not my partner” and that “there was someone in the corner.” The student then fell back asleep and later discovered that their partner had had an identical experience. These narratives express an anxiety around loss of sleep and communal living—anxieties all too familiar to busy college students.

One narrative of a student’s experiences at Marlboro North speaks to anxieties around being far from home on a remote, rural campus. The student describes not only a close bond with Ghost Cat, the benevolent feline spirit that is said to haunt the halls of Marlboro North, but also a more threatening supernatural force in the building. “I loved ghost cat,” writes the student in The Citizen, “and got the distinct feeling he was protecting and comforting me from the creepy business in the rest of the building.”

As with all forms of folklore, the ghostlore of Marlboro College is ultimately a form of cultural communication. In his book Interpreting Folklore, Alan Dundes states that folklore “provides a socially sanctioned framework for the expression of critical anxiety-producing problems as well as a cherished artistic vehicle for communicating ethos and worldview.”

Throughout the vast tapestry of Marlboro ghostlore, we see these functions in action. Each and every ghost story represents specific anxieties within the Marlboro student body. Some of these may be anxieties around college in general—noisy roommates, doomed relationships—while others are specific to Marlboro itself, particularly the narratives that focus on the school’s isolated location. As author Colin Dickey says in his book Ghostland, “We tell stories of the dead as a way of making sense of the living.”

Ghostlore helps students embrace the idea of college as liminal space, transforming the “strange exotic island” that is the Marlboro campus into a mysterious and magical place where anything can happen. Through ghostlore, the Marlboro student body grows closer as a community, ensuring that, much like their ghostly subjects, these stories will continue to haunt the Marlboro campus for many years to come.

Aaron Damon-Rush is a sophomore at Marlboro whose main area of interest is “narrative storytelling” in all of its forms— “basically just a fancy way of saying that I enjoy studying stories and the cultural significance they hold.” This article is adapted from an essay written by Aaron for the writing seminar Folklore in Literature and Pop Culture, for which he was awarded a Freshman-Sophomore Essay Prize in May. “Students in my spring 2019 Writing Seminar explored past and current definitions of ‘folk’ and reflected on how folklore and folk processes (transmission from person to person, variation, etc.) persist in the digital age,” says creative writing professor Bronwen Tate. “Aaron did a great job situating his findings within the context of scholarship, both on hauntings and on campus folklore.”

Death’s Covenant with Existence

“The ‘whole abyss’ between the present and death is like the abyss between myself and the Other,” says Alex Quick ’19 in his Plan paper titled “The Other in Time.” Alex explores the ethics of 20th-century philosophers Martin Heidegger and Emmanuel Levinas as he grapples with death, which Heidegger said serves as a “total structuring of my temporality.” “For Heidegger, the present moment always has a relationship to death when I am moving toward death in all of my moments,” says Alex, who after graduating joined the Peace Corps in Nepal. “The nothingness in death is inseparable from this present in being.” But for Levinas, death cannot be the primary force that structures time. “Death is not ushering the future into the present because death has no relationship to the present,” says Alex.

“The ‘whole abyss’ between the present and death is like the abyss between myself and the Other,” says Alex Quick ’19 in his Plan paper titled “The Other in Time.” Alex explores the ethics of 20th-century philosophers Martin Heidegger and Emmanuel Levinas as he grapples with death, which Heidegger said serves as a “total structuring of my temporality.” “For Heidegger, the present moment always has a relationship to death when I am moving toward death in all of my moments,” says Alex, who after graduating joined the Peace Corps in Nepal. “The nothingness in death is inseparable from this present in being.” But for Levinas, death cannot be the primary force that structures time. “Death is not ushering the future into the present because death has no relationship to the present,” says Alex.