Strengthening Health Systems in Fragile States

Text and photos by Jessica Flannery ’04

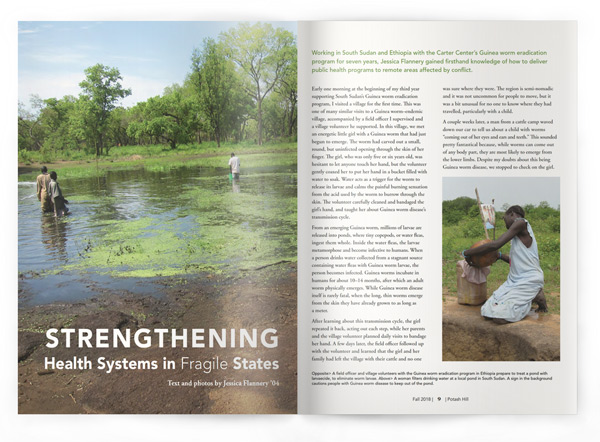

Working in South Sudan and Ethiopia with the Carter Center’s Guinea worm eradication program for seven years, Jessica Flannery gained firsthand knowledge of how to deliver public health programs to remote areas affected by conflict.

Early one morning at the beginning of my third year supporting South Sudan’s Guinea worm eradication program, I visited a village for the first time. This was one of many similar visits to a Guinea worm–endemic village, accompanied by a field officer I supervised and a village volunteer he supported. In this village, we met an energetic little girl with a Guinea worm that had just begun to emerge. The worm had carved out a small, round, but uninfected opening through the skin of her finger. The girl, who was only five or six years old, was hesitant to let anyone touch her hand, but the volunteer gently coaxed her to put her hand in a bucket filled with water to soak. Water acts as a trigger for the worm to release its larvae and calms the painful burning sensation from the acid used by the worm to burrow through the skin. The volunteer carefully cleaned and bandaged the girl’s hand, and taught her about Guinea worm disease’s transmission cycle.

From an emerging Guinea worm, millions of larvae are released into ponds, where tiny copepods, or water fleas, ingest them whole. Inside the water fleas, the larvae metamorphose and become infective to humans. When a person drinks water collected from a stagnant source containing water fleas with Guinea worm larvae, the person becomes infected. Guinea worms incubate in humans for about 10– 14 months, after which an adult worm physically emerges. While Guinea worm disease itself is rarely fatal, when the long, thin worms emerge from the skin they have already grown to as long as a meter.

After learning about this transmission cycle, the girl repeated it back, acting out each step, while her parents and the village volunteer planned daily visits to bandage her hand. A few days later, the field officer followed up with the volunteer and learned that the girl and her family had left the village with their cattle and no one was sure where they were. The region is semi-nomadic and it was not uncommon for people to move, but it was a bit unusual for no one to know where they had travelled, particularly with a child.

A couple weeks later, a man from a cattle camp waved down our car to tell us about a child with worms “coming out of her eyes and ears and teeth.” This sounded pretty fantastical because, while worms can come out of any body part, they are most likely to emerge from the lower limbs. Despite my doubts about this being Guinea worm disease, we stopped to check on the girl.

We were led to a little girl whose legs were covered in pustules, many with emerging worms. As the field officer slowly cleaned her legs, I realized that this little girl, who was in so much pain that she could barely walk, was the same girl who had been so lively just weeks before. She did not have worms coming out of eyes or ears or teeth, but she had worms coming from all over her body, nearly 25 altogether, most from her legs.

The field officer massaged out some of the worms, cleaned the sores with soap and water, used a topical antibiotic, made sure the girl was well bandaged, and taught her mother how to bandage her, as there was no volunteer in the camp. We made plans to return the next day with more supplies and to help residents select village volunteers. When we came back, less than 24 hours later, the girl was walking around outside her house, tentatively, but recovering.

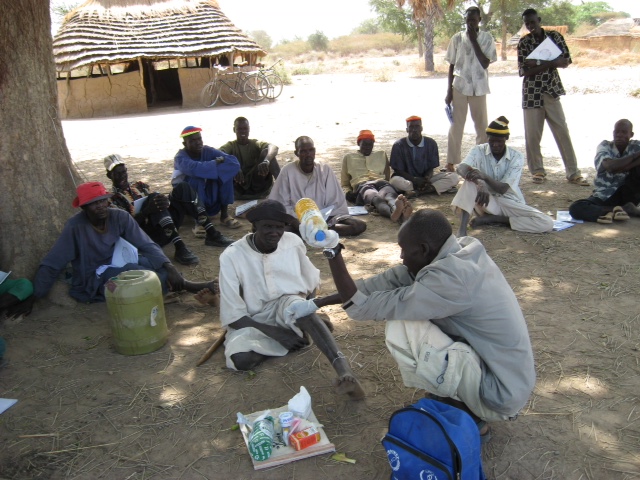

Treating this little girl led to working with her family and community to put systems into place to keep people from becoming infected: preventing those with emerging worms from entering water, providing simple filters to remove the water fleas from drinking water, and teaching people how to use and care for the filters. We also located potentially infected water sources in the area and targeted them for treatment with a larvaecide. We were able to identify other people connected with the girl who had Guinea worm, leading us to other communities.

At the time of our visit, in 2009, transmission had been stopped in all but four countries: Mali, Ethiopia, Chad, and South Sudan. The program’s focus on a single result—stopping Guinea worm transmission—led us to implement a clear set of interventions in a responsive and flexible manner, based on the conditions on the ground. This was supported by strong national leadership, sufficient resources, and close connections with communities.

At the same time, this girl, who was treated largely by having her legs cleaned with soap and water, had no access to a health facility, clean water, or other basic infrastructure that supports health. As we worked in communities, people with many other illnesses—women with obstetric emergencies, children with malaria, adults with tuberculosis—were brought to me for treatment because they had no access to health services. I am not a medical doctor and there was little I could do.

In Guinea worm eradication, I saw clearly just how possible it is to achieve health results when those results are focused and interventions are responsive, even in a complex, war-torn country with minimal infrastructure. It was just as clear that a health sector response to really improving health outcomes for all the people and communities we worked with would require the development of a sustainable health system.

For example, in the Guinea worm eradication program I worked with many staff who started out as field officers or village volunteers. One new field officer had trouble using a calculator and filling out, much less overseeing, reporting forms. Other staff teased him because he was slow in answering questions.

We worked together patiently, visiting volunteers and supervising villages. Other supervisors also supported him at times, offering different perspectives. He developed relationships with communities and leaders, and he worked diligently and constantly. After a while, when I visited his area, his volunteers were among the strongest and most motivated. In the communities he covered, effective filter use was high and community leaders were engaged. Eventually, he became a supervisor. Like many others I encountered, he was a living example of how capacity can be developed in an individual, and over time within a program and the system as a whole.

Working in this very successful program, I became interested in how whole health systems can be built within complex, conflict-impacted environments, often termed “fragile states.” In the final year of my doctoral program in public health, I worked as a consultant with the Global Financing Facility, a global partnership aiming to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and nutrition (RMNCAHN).

At the time, Liberia had just completed their national plan to improve RMNCAHN. One key question was how to build sustainable capacity for health systems management at the county level. Having experienced warand the Ebola epidemic, Liberia’s many years of technical assistance had often replaced capacity with foreign expertise, instead of developing local capacity. This happens largely because the success of a technical assistance agency is frequently equated with the quality of outputs, such as the number of reports submitted, often leading these agencies to do the local health management team’s work. In addition, “capacity development” is often used almost synonymously with training, or developing skills, while there are many other aspects to capacity such as the ability to draw on other people and to adapt to changing circumstances.

Working with Liberia’s Ministry of Health, we visited county health teams and helped to identify the challenges with health system management at the county level. We found that while staff had plenty of trainings, challenges persisted in structures, communication, adapting to difficult circumstances, and other aspects of capacity. These challenges called for a broader view of capacity development, drawing on a “complex adaptive systems” approach. This approach studies how different parts of a system impact each other in multiple different ways. A complex adaptive systems approach to capacity development looks at a range of aspects including relationships, integration of different parts of the system, and adaptability. This broader view aims to develop the capacity of the whole organization to sustain itself through staffing changes, conflict, and other shocks.

With the Ministry of Health, we developed a way to assess capacity using simulations and other practical tests, with the goal of allowing a technical assistance agency to be paid based on the county health team’s actual capacity instead of outputs. This way, the technical assistance agency can be flexible in figuring out ways to develop capacity more effectively and achieve results while developing actual capacity. We hope that this approach, which will be tested in the coming year, will help develop capacity that stays in place after technical assistance leaves.

This broader approach to health services helps fill in some of the gaps I saw while working in South Sudan: how can we move from supporting a single disease to supporting the whole system in a way that facilitates long-term change? It’s also an approach that is very much adapted to local context, allows for flexibility in implementation, and can be tested and adapted to solve ongoing challenges.

In my work in fragile states like South Sudan and Liberia, I have found that clarity of goal, along with space to try out different approaches, is critical. It’s also important to account for interactions between different, but interconnected, pieces: different types of knowledge, systems for learning, and systems for adaptation. It’s about using an approach that isn’t prescriptive, that lets people at all levels try things out and learn from them. Ultimately, a sustainable health system is more about engaging in a process than finding a single approach.

Jessica Flannery worked for the Carter Center in South Sudan for over five years. In March of 2018, she received her doctor of public health degree from the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. She is currently a consultant with the Global Financing Facility and World Bank.

From Child Soldier to Graduate Student

From Child Soldier to Graduate Student

Garang Buk Buk, a former child soldier in South Sudan’s brutal civil war, is a shining example of Jessica’s argument for the power of effective capacity development. Defying the odds, Garang worked with the Guinea worm eradication program, saving up enough money to pay for his undergraduate education in Nairobi, Kenya. Now he has been accepted to Emory University for a master’s in development practice, with the goal of returning to South Sudan to better his community. Learn more about the New Jersey high school class that is supporting Garang’s graduate school efforts, and contribute at: gofundme.com/get-garang-to-emory.

Law and Order in North Africa

“My greatest hope is to see the establishment of stable political systems that exist to serve the needs of the citizens, rather than to perpetuate themselves and protect their own interests,” says Amelia Fanelli ’18 who focused her Plan on the politics of North African regimes. “In my opinion, any movement in this direction would be a positive development.” Although she had been drawn to politics and law since childhood, as a World Studies Program student Amelia did her internship in Tunisia, and became interested in the constitutions of North African nations. “After returning from Tunisia, I was unsure how I would shape my experiences into a piece of written work, and I found the answer through combining my interest in politics and North Africa with my interest in written law,” she says.

“My greatest hope is to see the establishment of stable political systems that exist to serve the needs of the citizens, rather than to perpetuate themselves and protect their own interests,” says Amelia Fanelli ’18 who focused her Plan on the politics of North African regimes. “In my opinion, any movement in this direction would be a positive development.” Although she had been drawn to politics and law since childhood, as a World Studies Program student Amelia did her internship in Tunisia, and became interested in the constitutions of North African nations. “After returning from Tunisia, I was unsure how I would shape my experiences into a piece of written work, and I found the answer through combining my interest in politics and North Africa with my interest in written law,” she says.